Abstract

Aims

Intravenous procainamide and amiodarone are drugs of choice for well-tolerated ventricular tachycardia. However, the choice between them, even according to Guidelines, is unclear. We performed a multicentre randomized open-labelled study to determine the safety and efficacy of intravenous procainamide and amiodarone for the acute treatment of tolerated wide QRS complex (probably ventricular) tachycardia.

Methods and results

Patients were randomly assigned to receive intravenous procainamide (10 mg/kg/20 min) or amiodarone (5 mg/kg/20 min). The primary endpoint was the incidence of major predefined cardiac adverse events within 40 min after infusion initiation. Of 74 patients included, 62 could be analysed. The primary endpoint occurred in 3 of 33 (9%) procainamide and 12 of 29 (41%) amiodarone patients (odd ratio, OR = 0.1; 95% confidence interval, CI 0.03–0.6; P = 0.006). Tachycardia terminated within 40 min in 22 (67%) procainamide and 11 (38%) amiodarone patients (OR = 3.3; 95% CI 1.2–9.3; P = 0.026). In the following 24 h, adverse events occurred in 18% procainamide and 31% amiodarone patients (OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.15–1.61; P: 0.24). Among 49 patients with structural heart disease, the primary endpoint was less common in procainamide patients (3 [11%] vs. 10 [43%]; OR: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.04–0.73, P = 0.017).

Conclusions

This study compares for the first time in a randomized design intravenous procainamide and amiodarone for the treatment of the acute episode of sustained monomorphic well-tolerated (probably) ventricular tachycardia. Procainamide therapy was associated with less major cardiac adverse events and a higher proportion of tachycardia termination within 40 min.

Keywords: Ventricular tachycardia, Amiodarone, Procainamide, Acute treatment

Introduction

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is an uncommon but dangerous medical condition, with an extremely variable clinical presentation, from being almost asymptomatic to producing cardiac arrest. When the clinical condition as the patient seeks medical attention is not compromised (i.e. blood pressure is maintained and there are no overt signs of heart failure) VT is usually referred to as ‘stable’ or ‘well tolerated’. Although it may remain stable for minutes or even hours, the condition produces justified concern and requires prompt intervention for termination because haemodynamic instability and deterioration leading to collapse can develop at any time. Termination can be achieved with electrical cardioversion, antiarrhythmic medications, and pacing techniques. Following guidelines recommendations, intravenous procainamide, and amiodarone are drugs of choice for the treatment of haemodynamically stable VT with a class II recommendation.1–4 However, although both drugs are well known and have been in conventional clinical use for decades,5–10 there is no scientific evidence to base the use of one drug vs. the other in this clinical context. Controlled trials with amiodarone have been performed in other clinical contexts11–14 (i.e. hypotensive VT or cardiac arrest) and procainamide has been compared with other antiarrhythmic drugs,7 but no controlled prospective trial have focused in comparing these two agents in well-tolerated VT.

The PROCAMIO is a multicentre, prospective and randomized study that compares the safety and efficacy of intravenous procainamide and amiodarone in the acute treatment of wide QRS complex monomorphic tachycardias (presumably VT) which are haemodynamically well tolerated.

Sustained monomorphic VT always involves a differential diagnosis with supraventricular tachycardia. However, the majority of wide QRS complex tachycardias presenting at Emergency Departments are in fact VTs, even if the haemodynamic tolerance is acceptable.15 As such, the present trial refers to ‘wide QRS complex tachycardia (probably of ventricular origin)’ rather than to ‘VT’, assuming some uncertainty in diagnosis.

Methods

Study design and randomization

Patients were randomly assigned in an open-labelled fashion to receive either intravenous procainamide (single dose 10 mg/kg over 20 min) or intravenous amiodarone (single dose 5 mg/kg over 20 min) with a 1:1 ratio. The study period was 40 min from infusion initiation (20 min for drug administration and 20 min following administration). There was an observation period of 24 h after the end of the study period.

The randomization procedure was as follows: since a rapid decision has to be made as to the drug assigned, groups of 10 numbered and closed envelopes were deposited at each Centre (and were replaced as necessary) so, whenever a candidate appeared, the investigator could open the next envelope containing the assigned therapy. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Both Cardiology and Emergency Departments participated at different Centres in order to include a representative patient population. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at each centre, and informed consent of the subjects was obtained before enrolment. The trial was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00383799). PROCAMIO investigators are listed in Appendix.

Patient selection

Patients with regular wide QRS complex tachycardia that required medical attention were included in the study if they had the following conditions: (i) regular heart rhythm with rate ≥120 bpm; (ii) tachycardia QRS duration ≥120 ms; (iii) good haemodynamic tolerance defined as: (a) systolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, (b) absence of dyspnoea at rest, (c) absence of peripheral hypoperfusion signs, and (d) no severe anginal symptoms; and (iv) age >18 years. Exclusion criteria included: (i) treatment with either intravenous amiodarone or intravenous procainamide during the previous 24 h; (ii) poor haemodynamic tolerance that required urgent termination; (iii) presence of irregular tachycardia, (iv) tachycardia that was considered as supraventricular due to physician criteria (based mostly on response to vagal manoeuvres or adenosine, electrocardiographic analysis was not particularly encouraged within the study), (v) contraindications to the drugs under study, and (vi) the patient that did not want to cooperate and/or sign the consent form.

Definitions and treatments

Major cardiac adverse events were considered to be probably related to the drugs in study and predefined as one of the following: (i) clinical signs of peripheral hypoperfusion, (ii) heart failure signs: dyspnoea at rest and/or orthopnoea associated with signs of pulmonary congestion (presence or increase of rales and/or decrease in blood oxygen saturation), (iii) severe hypotension defined as systolic blood pressure ≤70 mmHg if the pre-treatment systolic pressure was ≤100 mmHg or systolic blood pressure ≤80 mmHg if the pre-treatment systolic pressure was >100 mmHg, (iv) tachycardia acceleration of >20 bpm of its mean value, and (v) appearance of fast polymorphic VT.

Drug infusion was stopped by protocol if any of the following occurred: (i) termination of the tachycardia during the infusion period; (ii) complete administration of the amount of drug programmed; and (iii) presence of a major cardiac adverse event. If the tachycardia did not terminate during the study period, the patient was treated following physician's criteria. Nevertheless, electrical cardioversion was strongly recommended.

Response to treatment was evaluated as follows: termination was defined as conversion to the patient's known or presumed usual heart rhythm (e.g. sinus, atrial fibrillation) within the study period. If the tachycardia terminated within 20 min of drug infusion initiation and recurred within 20 min following infusion ending, then the treatment was considered unsuccessful.

A 12 lead ECG was obtained before including the patient in the study. During the study period, patients were constantly monitored. A 12 lead ECG or a rhythm strip of at least one lead was obtained every 10 min. Likewise, a 12 lead ECG was obtained at the time the tachycardia ended. Blood pressure (at least systolic) was measured every 3 min.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was to compare the incidence of major cardiac adverse events between both treatments. Secondary endpoints were the following: (i) to compare the efficacy of both drugs in relation to the acute termination of the tachycardia episode and (ii) to compare the incidence of total adverse events during the observation period. Adverse events were analysed and classified blinded to the patient study group.

Sample size calculations and premature study termination

The sample size calculation for this study had significant uncertainties at the time the study was designed. There was only one randomized trial with intravenous procainamide in tolerated VT, with considerable adverse events.7 Observational studies with small number of patients had reported extremely good tolerance of intravenous amiodarone.8,16–18 So we hypothesized 20 and 5% adverse event rate in the procainamide and amiodarone groups. Based on these assumptions, 302 patients were needed to detect a difference of 15% in major adverse events between both groups.

After nearly 6 years including patients at 26 participating Centres, 74 patients had been randomized and a trend towards a decrease in inclusion rate was observed. At this point, the Steering Committee decided to stop patient recruitment and analyse the results.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for continuous variables was recorded as means and standard deviations, as well as medians. Comparisons between the two treatment groups were performed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All P-values are two tailed. Categorical data were summarized as frequencies and percentages, and comparisons between groups were performed with the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher's exact test and non-conditional logistic regression to calculate odd ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI). As sensitivity analyses, we estimated the OR for both treatments after several assumptions: (i) including patients initially excluded, (ii) including only patients with structural heart disease, and (iii) adjusting for several confounding factors (adjusted OR). Data were analysed with SPSS (version 17.0) and JMP (version 12.0.1).

Results

Study population

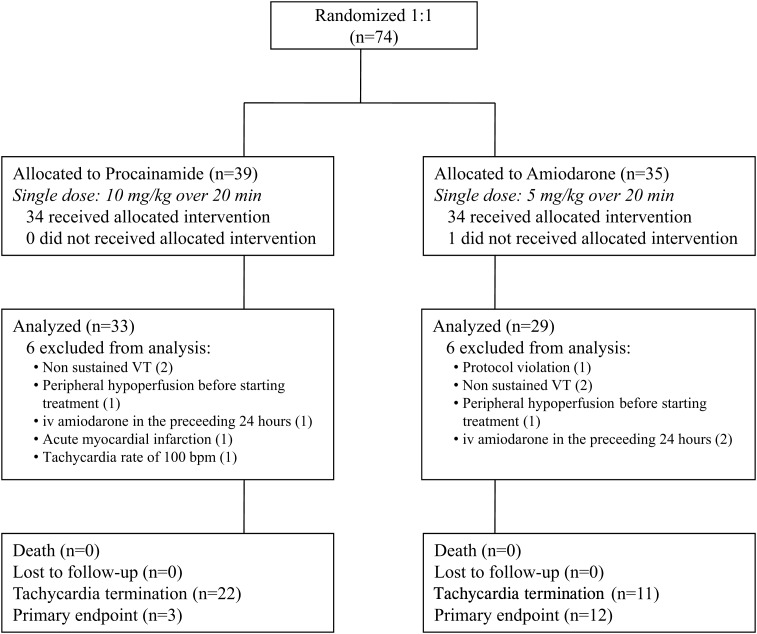

Seventy-four patients that required medical attention at 16 of the 29 participating hospitals were included in the study. Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of patients entering the trial. One patient did not receive the assigned drug (amiodarone) because he/she required urgent cardioversion before drug administration. Twelve patients (6 in the amiodarone group and 6 in the procainamide group) were excluded from the analysis due to protocol violation or the development of exclusion criteria before drug treatment (Figure 1). Sixty-two patients were analysed. Thirty-three patients were assigned to procainamide and 29 to amiodarone. Their relevant clinical data are provided in Table 1. Most variables, including β-blockers and vasodilators, were evenly distributed. Age and previous oral amiodarone differed and were included in sensitivity analyses (see below). Time from arrival to start of infusion was 87 ± 21 min for procainamide and 115 ± 36 min for amiodarone patients (P = 0.58). In order to obtain an idea of the true incidence of VT, ECGs of tachycardias were reviewed off-line by two electrophysiologists (F.A., R.P.) who classified the episodes as probably/definite VT or SVT. 90.3% of the episodes were considered VT (88% procainamide, 93% amiodarone, P = 0.49).

Figure 1.

Summary of patient recruitment and results.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Procainamide (n = 33) | Amiodarone (n = 29) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 ± 16 | 69 ± 11 | 0.08 |

| Emergency room | 26 (79) | 24 (83) | 0.7 |

| Structural heart disease | 26 (79) | 23 (79) | 0.96 |

| Coronary artery disease | 15 (45) | 15 (52) | 0.62 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 6 (18) | 4 (14) | 0.64 |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.94 |

| Other | 4 (12) | 3 (10) | 0.83 |

| LVEF | 0.40 ± 0.13 (n = 29) | 0.37 ± 0.15 (n = 24) | 0.37 |

| SBP at admission (mmHg) | 115 ± 16 | 116 ± 19 | 0.85 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 179 ± 31 | 176 ± 32 | 0.75 |

| QRS (ms) | 153 ± 26 | 165 ± 32 | 0.13 |

| QRS morphology | 0.37 | ||

| Right bundle branch block | 24 (73) | 18 (62) | |

| Left bundle branch block | 9 (27) | 11 (38) | |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 0.6 (n = 28) | 4.6 ± 0.7 (n = 26) | 0.23 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 ± 0.5 (n = 29) | 1.4 ± 0.6 (n = 26) | 0.29 |

| Lidocaine during transport to hospital | 0 | 0 | — |

| Adenosine at emergency room | 4 (12) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Previous oral pharmacological treatment | |||

| Amiodarone | 0 | 5(17) | 0.02 |

| β-Blockers | 11 (33) | 10 (34) | 0.92 |

| ACE-inhibitors/ARBs | 16 (48) | 14 (48) | 0.89 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2 (6) | 2 (7) | 0.89 |

| Other class I or III antiarrhythmic drugs | 0 | 0 | — |

Values are n (%) and mean ± SD.

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Primary endpoint

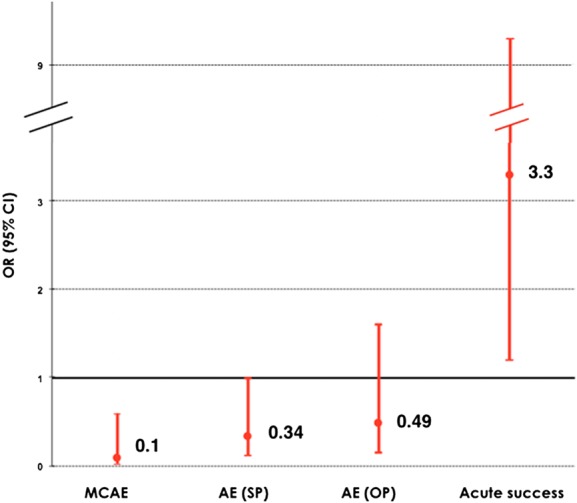

Fifteen patients (24%) had major cardiac adverse events during the study period. Major cardiac adverse events occurred less frequently in patients treated with intravenous procainamide (9 vs. 41%; OR = 0.1; 95% CI: 0.03–0.6; P = 0.006, Tables 2 and 3, Figure 2). Events are detailed in Table 4: severe hypotension requiring immediate electrical cardioversion was the most frequent adverse event in both groups, no death occurred.

Table 2.

Safety and efficacy of study drugs in the entire population

| All patients (n = 62) | Procainamide (n = 33) | Amiodarone (n = 29) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major cardiac adverse events during study period | 15 (24) | 3 (9) | 12 (41) | 0.006 |

| Total adverse events during study period | 22 (35) | 8 (24) | 14 (48) | 0.052 |

| Time to adverse event (min) | 17 ± 9 | 17 ± 12 | 16 ± 7 | 0.7 |

| Tachycardia termination during study period | 33 (53) | 22 (67) | 11 (38) | 0.026 |

| Time to tachycardia termination (min) | 14 ± 9 | 14 ± 10 | 16 ± 5 | 0.3 |

| Total adverse events during the observation period | 15 (24) | 6 (18) | 9 (31) | 0.24 |

Values are n (%) and mean ± SD.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for major cardiac adverse events with procainamide taking amiodarone as the reference treatment

| n | MCAE in procaniamide group (%) | MCAE in amiodarone group (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Including all patients | 74 | (6/39) 15.4% | (15/35) 42.8% | 0.24 (0.08–0.73) | 0.011 |

| Including only patients who were analysed | 62 | (3/33) 9.1% | (12/29) 41.4% | 0.14 (0.03–0.57) | 0.006 |

| Including only patients with structural heart disease | 49 | (3/26) 11.5% | (10/23) 43.5% | 0.17 (0.04–0.73) | 0.017 |

| OR adjusted for age and sex | 62 | (3/33) 9.1% | (12/29) 41.4% | 0.10 (0.02–0.48) | 0.004 |

| OR adjusteda | 62 | (3/33) 9.1% | (12/29) 41.4% | 0.11 (0.02–0.55) | 0.008 |

MCAE, mayor cardiac adverse event.

aAdjusted by sex, age, structural heart disease, and previous oral amiodarone.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio and confidence intervals of adverse events and tachycardia termination of procainamide patients compared with amiodarone patients. AE, adverse events; MCAE, major cardiac adverse events; SP, study period (40 min); OP, observation period (24 h).

Table 4.

Cardiac adverse events during the study period (40 min)

| Adverse event | Procainamide | Amiodarone |

|---|---|---|

| Major cardiac adverse events during study period | ||

| Acute pulmonary oedema requiring DCCV | 0 | 2 |

| Severe hypotension requiring cessation of infusion | 1 | 1 |

| Severe hypotension requiring immediate DCCV | 2 | 6a |

| Peripheral hypoperfusion and/or dyspnoea with severe hypotension requiring immediate DCCV | 0 | 3 |

| Other adverse events during study period | ||

| Hypotension that did not require cessation of infusion or DCCV | 5 | 2 |

| Adverse events during observation period | ||

| Acute pulmonary oedema with peripheral hypoperfusion | 1 | 1 |

| Dyspnoea with peripheral hypoperfusion | 1 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 3 | 5 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 1 | 0 |

| Arrhythmic storm and cardiogenic shock | 0 | 1 |

| Neumothorax | 0 | 1 |

| Acute myocardial infarction 4 h after drug administration | 0 | 1 |

DCCV, direct current cardioversion.

aDCCV was cancelled in one patient due to spontaneous reversion to sinus rhythm.

Sensitivity analyses were performed for the association between procainamide treatment and major cardiac adverse events compared with amiodarone. The reduction of events in patients treated with procainamide compared with amiodarone did not change if we included all patients, or after adjusting by age, sex, structural heart disease, and previous treatment with oral amiodarone (Table 3).

Secondary endpoints

Tachycardia termination

Termination of VT during the study period occurred in 33 patients (53%). Efficacy was significantly higher in patients treated with intravenous procainamide: 67 vs. 38%; OR = 3.3; 95% CI 1.2–9.3; P = 0.026, Table 2, Figure 2.

An analysis was performed including all patients entering the trial, which did not change the results (68 vs. 42%; OR = 2.7; 95% CI 1.04–7.08; P = 0.041).

Total adverse events during the study period

Hypotension not requiring cessation of infusion occurred in seven patients adding to a total number of adverse events of eight in the procainamide group and 14 in the amiodarone group (24 vs. 48%; OR = 0.34; 95% CI 0.12–1.00; P = 0.052, Tables 2 and 4, Figure 2).

Adverse events during the observation period

Fifteen patients (24%) presented adverse events during the observation period (18% procainamide, 31% amiodarone group, OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.15–1.61; P = 0.24, Tables 2 and 4, Figure 2).

Subgroup analysis in patients with structural heart disease

Among patients with structural heart disease, major cardiac adverse events were significantly lower during the study period in patients treated with intravenous procainamide (11 vs. 43%; OR: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.04–0.73, P = 0.017, Table 5). There were no significant differences in total adverse effects during the study period or during the observation period (31 vs. 48%, P = 0.22, and 23 vs. 30%, P = 0.56, respectively, Table 5). Ventricular tachycardia termination tended to be higher with intravenous procainamide (65 vs. 39%, OR = 2.94, 95% CI 0.92–9.4; P = 0.069, Table 5).

Table 5.

Safety and efficacy of study drugs in patients with structural heart disease

| All patients (n = 49) | Procainamide (n = 26) | Amiodarone (n = 23) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major cardiac adverse events during study period | 13 (26) | 3 (11) | 10 (43) | 0.017 |

| Total adverse events during study period | 19 (38) | 8 (31) | 11 (48) | 0.22 |

| Time to adverse event (min) | 17 ± 10 | 19 ± 13 | 16 ± 7 | 0.6 |

| Tachycardia termination during study period | 26 (53) | 17 (65) | 9 (39) | 0.069 |

| Time to tachycardia termination (min) | 15 ± 10 | 15 ± 11 | 16 ± 5 | 0.9 |

| Total adverse events during the observation period | 13 (26) | 6 (23) | 7 (30) | 0.56 |

Discussion

This study shows for the first time in a randomized controlled trial that when intravenous procainamide and amiodarone, at usual clinical doses, are compared for the acute treatment of spontaneous episodes of well-tolerated wide QRS complex tachycardias, presumably VT: (i) procainamide is associated with less major cardiac adverse events; (ii) procainamide is more efficacious in terminating the tachycardia episode; (iii) these findings equally apply to the subgroup of patients with structural heart disease.

Comparison with previous available information

The information regarding intravenous procainamide and amiodarone for the acute termination of well-tolerated spontaneous sustained VT is limited.19 The only study that has compared procainamide and amiodarone is a retrospective multicentre historical cohort trial that gathered information from 90 patients.20 In that study, amiodarone caused severe hypotension requiring emergency electrical cardioversion in 6% and one patient died with asystole. There is only one additional series using intravenous amiodarone: this retrospective single cohort analysis identified 41 patients that received 300 mg.21 Severe hypotension requiring emergency electrical cardioversion occurred in 7/41 cases (17%). Our figure of 41% major cardiac adverse events in the amiodarone arm is higher than in these reports. One possible explanation is that in our prospective study, we prespecified which symptoms and levels of hypotension were considered a major event, whereas in retrospective trials major adverse events were recognized by the need of electrical cardioversion. In addition, the retrospective nature of these studies imposes significant limitations: 47 patients (52%) in one study20 had received another antiarrhythmic drug and the mean dose was 2.0 mg/kg in patients in whom amiodarone was ineffective, smaller than the 5 mg/kg used in our trial; in another study21 the duration of the drug infusion lasted up to 60 min.

Regarding efficacy, amiodarone was effective in 23% in whom it was the first drug tried (25% considering all patients)20 and in 15% within 20 min (29% within 1 h).21 Our figure of 38% success rate, slightly higher, could also be related to the higher doses and shorter infusion time.

The information regarding procainamide for the acute termination of spontaneous well-tolerated sustained VT is even more limited, including a retrospective comparison with amiodarone20 and two studies comparing procainamide with lidocaine.7,22 Major cardiac adverse events occurred in 137 and 17%.20 Our figure of 9% is slightly lower. Efficacy was reported in 76 and 57% in retrospective studies20,22 and in 80% in a prospective study.7 Our figure of 67% VT termination is consistent with these reports.

In light of the above findings, procainamide and amiodarone have been considered in published Guidelines as agents that could be used for the acute therapy of VT. Although the most recent Guidelines indicate that electrical cardioversion should be the first-line approach, they also consider antiarrhythmic drug therapy in this situation.23

Characteristics of our study: selected dosages and administration

Since the most important concern in treating patients with cardiac arrhythmias is safety, the primary endpoint of the study was focused on major cardiac adverse events.

There is general agreement that for a condition, such as tolerated VT that is potentially but not immediately life threatening, the duration of infusion can be longer than a ‘bolus’ but relatively short. Studies and guideline recommendations have ranged between 10 and 60 min infusion duration,2,4,7,20,21 we chose a 20 min duration period which seemed a reasonable compromise for the workload of most emergency departments. Amiodarone doses have ranged between 150 mg and a bolus of 5 mg/kg.4,13 The dose we chose, 5 mg/kg infused during 20 min, approximated the 300 mg recommendation made by the European Resuscitation Council.2 It is conceivable that a lower amiodarone dose could have resulted in less adverse effects, but probably also in lower efficacy not changing the main message of the trial. Procainamide doses have also varied in the literature, ranging between ‘at least’ 500 mg20 and ‘up to 17 mg/k’.4 We chose the 10 mg/k used by Gorgels et al.,7 but infused over 20 min.

Unexpected findings?

It is clear from the hypothesis and the sample size considerations that we did not expect such a high incidence of major adverse effects in the amiodarone arm. Leak et al.16 reported on using a bolus of 150 mg of amiodarone in 11 critically ill patients and stated that ‘hypotension, cardiac failure and bradyarrhythmias were not induced by this treatment’. In 38 critically ill patients, but having atrial tachyarrhythmias, a mean of 242 mg of amiodarone was shown to control heart rate without hypotension in any patient. In a series of 15 patients with recurrent VT, amiodarone at an initial dose of 5 mg/k over 15 min resulted in no significant adverse effect.8 In severely hypotensive recurrent VT, amiodarone produced less hypotension than bretilium.12 We hypothesized that if amiodarone was safe in these very sick patients it was going to be so in the stable patient with tolerated VT. However, in retrospect, some findings can explain our results: (i) when the arrhythmia is immediately life threatening, an antiarrhythmic action can produce such a benefit that overcomes potential adverse effects; (ii) in studies performed during resuscitation13,14 all patients had previously received intravenous catecolamines (adrenaline) and in critically ill patients12 most were receiving catecolamines: these drugs may have counteracted the hypotensive effects of amiodarone.

Limitations

The study included less number of patients that were required according to our sample size calculations. Several reasons probably accounted for this: (i) extension of emergency protocols to treat these patients on the ambulance; in these protocols only amiodarone was allowed, precluding participation in the trial; (ii) fast turnover of medical personnel at emergency departments. In any event, recruitment rate was less than expected and declining, which prompted us, after nearly 6 years including patients, to end the study before having reached the number originally planned. In looking now to retrospectives series published in recent years, a low number of patients of this kind seems to be the rule, so it is possible that the condition is indeed rare.

The study design was randomized but not blinded. To avoid assigning less importance to adverse events related to one drug, major adverse events and reasons to stop the study drug were precisely predefined. In fact, since physicians are more familiar with intravenous amiodarone, if anything, less relevance to adverse events related to this drug could have been expected.

Conclusions

In this randomized prospective study comparing intravenous procainamide and amiodarone for the treatment of the acute episode of sustained monomorphic well-tolerated wide QRS tachycardia (probably VT), procainamide therapy was associated with less major cardiac adverse events and a higher proportion of tachycardia termination within 40 min.

Authors' contributions

M.O. performed statistical analysis, coordinated data collection and acquired the data; J.A. handled funding and supervision, designed the study; J.A., A.M., F.A., B.C.-V., C.d.A., and R.P. oversaw its conduct, designed the study, and made critical revision of the manuscript for key intellectual content; M.O., J.A., A.M., F.A., B.C.-V., C.d.A., and R.P. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; M.O. and J.A. drafted the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundación para la Investigación Biomédica del Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain; Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI060675), Madrid, Spain; and the Arrhythmia Division of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, Madrid, Spain.

Conflict of interest: none to declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dolores Vigil, MD, for her assistance in the statistical design of the study, Teresa Barrio, MD, for her assistance in the statistical analysis, and all of the PROCAMIO trial investigators for their contribution to this trial.

Appendix

PROCAMIO Participating Investigators and Centres: R. Peinado, O. Madridano, Hospital General Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain; B. Coll-Vinent, L. Mont, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain; L. Serrano, A. García Alberola, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia, Spain; A. Martín, Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid, Spain; Spain; M. Alvarez, L. Sánchez, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain; J. Villacastín, JJ G-Armengol, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain; C. Suero, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga, Spain; J. Muñoz, F. Atienza, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain; F. Ruiz, Hospital de Valme, Sevilla, Spain; E. Ruiz, A. Moya, Hospital Vall d'Hebrón, Barcelona, Spain; N. Laín, J Aguilar, E. Castellanos, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain; R. Salguero, Hospital Doce de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; A. Pedrote, A. Caballero, Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla, Spain; J. Carbajosa, Hospital General, Alicante, Spain; J.V. Ortega Liarte, Hospital Los Arcos, San Javier, Murcia, Spain; Manuel Cancio, Hospital de Donostia, San Sebastián, Spain.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on Behalf of the PROCAMIO Study Investigators, R. Peinado, O. Madridano, L. Serrano, A. García Alberola, A. Martín, M. Alvarez, L. Sánchez, J. Villacastín, JJ G-Armengol, C. Suero, J. Muñoz, F. Atienza, F. Ruiz, E. Ruiz, A. Moya, N. Laín, J Aguilar, E. Castellanos, R. Salguero, A. Pedrote, A. Caballero, J. Carbajosa, J.V. Ortega Liarte, and Manuel Cancio

References

- 1. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 6: advanced cardiovascular life support: section 5: pharmacology I: agents for arrhythmias. Circulation 2000;102(Suppl. 8):I112–I128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nolan JP, Deakin CD, Soar J, Böttiger BW, Smith G. European Resuscitation Council. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2005;67(Suppl. 1):S39–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, Gregoratos G, Klein G, Moss AJ, Myerburg RJ, Priori SG, Quinones MA, Roden DM, Silka MJ, Tracy C, Smith SC Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Antman EM, Anderson JL, Hunt SA, Halperin JL, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo JL, Zamorano JL, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force, European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines, European Heart Rhythm Association, Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2006;114:e385–e484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122(Suppl. 3):S729–S767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wellens HJJ, Bär FW, Lie KL, Durrer DR, Dohmen H. Effect of procainamide, propranolol and verapamil on mechanism of recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1977;40:579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Dissociation of termination and prevention of inducibility of sustained ventricular tachycardia with infusion of procainamide: evidence for distinct mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;19:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gorgels AP, Van den Dool A, Hofs A, Mulleneers R, Smeets JLRM, Vos MA, Wellens HJJ. Comparison of procainamide and lidocaine in terminating sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morady F, Scheinman MM, Shen E, Shapiro W, Sung RJ, DiCarlo L. Intravenous amiodarone in the acute treatment of recurrent symptomatic ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mostow ND, Vrobel TR, Noon D, Rakita L. Intravenous amiodarone: hemodynamics, pharmacokinetics, electrophysiology, and clinical utility. Clin Prog Electrophysiol Pacing 1986;4:342–357. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Remme WJ, Kruyssen HACM, Look MP, Van Hoogenhuyze DCA, Krauss XH. Hemodynamic effects and tolerability of intravenous amiodarone in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Am Heart J 1991;122:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levine JH, Massumi A, Scheinman MM, Winkle RA, Platia EV, Chilson DA, Gomes A, Woosley RL. Intravenous amiodarone for recurrent sustained hypotensive ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kowey PR, Levine JH, Herre JM, Pacifico A, Lindsay BD, Plumb VJ, Janosik DL, Kopelman HA, Scheinman MM. Randomised, double-blind comparison of intravenous amiodarone and bretylium in the treatment of patients with recurrent, hemodynamically destabilizing ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Circulation 1995;92:3255–3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dorian P, Cass D, Schwartz B, Cooper R, Gelaznikas R, Barr A. Amiodarone as compared with lidocaine for shock-resistant ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2002;346:884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kudenchuk PJ, Cobb LA, Copass MK, Cummins RO, Doherty AM, Fahrenbruch CE. Amiodarone for resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1999;341:871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akhtar M, Shenasa M, Jazayeri M, Jazayeri M, Caceres J, Tchou PJ. Wide QRS complex tachycardia. Reapraisal of a common clinical problem. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leak D. Intravenous amiodarone in the treatment of refractory life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias in the critically ill patients. Am Heart J 1986;111:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clemo HF, Wood MA, Gilligan DM, Ellenbogen KA. Intravenous amiodarone for acute heart rate control in the critically ill patient with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Gowda RM. Amiodarone for pharmacological cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2003;89:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. deSouza IS, Martindale JL, Sinert R. Antidysrhythmic drug therapy for the termination of stable, monomorphic ventricular tachycardia: a systematic review. Emerg Med J 2015;32:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marill KA, deSouza IS, Nishijima DK, Senecal EL, Setnik GS, Stair TO, Ruskin JN, Ellinor PT. Amiodarone or procainamide for the termination of sustained stable ventricular tachycardia: an historical multicenter comparison. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tomlinson DR, Cherian P, Betts TR, Bashir Y. Intravenous amiodarone for the pharmacological termination of haemodynamically-tolerated sustained ventricular tachycardia: is bolus dose amiodarone an appropriate first-line treatment? Emerg Med J 2008;25:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Komura S, Chinushi M, Furushima H, Hosaka Y, Izumi D, Iijima K, Watanabe H, Yagihara N, Aizawa Y. Efficacy of procainamide and lidocaine in terminating sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ J 2010;74:864–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2793–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]