Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is more cost-effective than stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for initial treatment of inoperable, localized hepatocellular carcinoma despite the high local control of SBRT shown in studies to date; however, SBRT is cost-effective relative to RFA to salvage locally recurrent tumors after RFA.

Abstract

Purpose

To assess the cost-effectiveness of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) versus radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for patients with inoperable localized hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who are eligible for both SBRT and RFA.

Materials and Methods

A decision-analytic Markov model was developed for patients with inoperable, localized HCC who were eligible for both RFA and SBRT to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the following treatment strategies: (a) SBRT as initial treatment followed by SBRT for local progression (SBRT-SBRT), (b) RFA followed by RFA for local progression (RFA-RFA), (c) SBRT followed by RFA for local progression (SBRT-RFA), and (d) RFA followed by SBRT for local progression (RFA-SBRT). Probabilities of disease progression, treatment characteristics, and mortality were derived from published studies. Outcomes included health benefits expressed as discounted quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), costs in U.S. dollars, and cost-effectiveness expressed as an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the findings.

Results

In the base case, SBRT-SBRT yielded the most QALYs (1.565) and cost $197 557. RFA-SBRT yielded 1.558 QALYs and cost $193 288. SBRT-SBRT was not cost-effective, at $558 679 per QALY gained relative to RFA-SBRT. RFA-SBRT was the preferred strategy, because RFA-RFA and SBRT-RFA were less effective and more costly. In all evaluated scenarios, SBRT was preferred as salvage therapy for local progression after RFA. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY gained, RFA-SBRT was preferred in 65.8% of simulations.

Conclusion

SBRT for initial treatment of localized, inoperable HCC is not cost-effective. However, SBRT is the preferred salvage therapy for local progression after RFA.

© RSNA, 2017

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and third leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide (1,2). The incidence of HCC is increasing in the United States, a trend that is expected to continue given the rising prevalence of hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis (3). Fewer than half of patients with hepatitis C virus are aware of their infection, and many who know their status do not receive appropriate treatment of their disease because of a lack of access to adequate care and the high costs of newer antiviral therapies (4,5). HCC is a distinct clinical challenge because of its unique etiology, natural history, sensitivity to local therapies, and specific disease treatment guidelines and algorithms (6).

Since most HCC patients are not candidates for resection or transplantation due to cirrhosis, comorbidities, or long wait times for transplantation, they and their providers must decide which nonsurgical local and regional interventions to use for treatment (7). Liver ablation is considered first-line treatment for localized HCC that is not suitable for surgery (6). Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) induces coagulative necrosis of tumor through thermal ablation and is the preferred technique for treating small HCC lesions. However, RFA is an invasive procedure, often requiring general anesthesia, and cannot provide adequate control of larger lesions (8). Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a new technology that safely delivers ablative radiation doses to tumors while minimizing the dose to normal liver tissue. Early results with SBRT show high local control even for large tumors, and it is, therefore, becoming an accepted local therapy for hepatic lesions (9). However, because of the complex treatment planning, quality assurance, and delivery procedures its use requires, SBRT has substantially higher associated costs than does RFA and is among the main drivers of rising costs in the field of radiation oncology (10).

To our knowledge, there are no head-to-head prospective clinical trials comparing these two ablative local treatment strategies. However, results of a recent retrospective study (9) demonstrated improved local control with SBRT relative to RFA. Given SBRT’s better efficacy but higher costs, we assessed the cost-effectiveness of SBRT versus RFA for patients with inoperable localized HCC who were eligible for both SBRT and RFA.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Decision Model

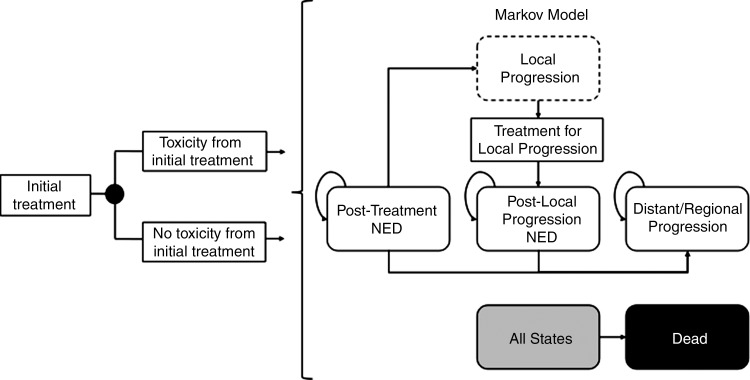

We constructed a decision analytic Markov model by using software (TreeAge Pro; TreeAge, Williamstown, Mass) to track a hypothetical cohort of patients with inoperable localized HCC who were amenable to treatment with both RFA and SBRT (Fig 1). The decision involved both the initial treatment modality and the modality used in cases of local progression. Hence, we evaluated the health benefits and costs of four strategies: (a) SBRT as initial treatment followed by SBRT for local progression (SBRT-SBRT), (b) RFA followed by RFA for local progression (RFA-RFA), (c) SBRT followed by RFA for local progression (SBRT-RFA), and (d) RFA followed by SBRT for local progression (RFA-SBRT).

Figure 1:

Abbreviated decision tree and Markov model. After initial treatment with either RFA or SBRT, patient experiences risk of toxicity before entering the Markov model, where further disease progression is simulated. NED = no evidence of disease.

Disease Model

Immediately after initial treatment with RFA or SBRT, the cohort of patients was considered to have NED. We assumed that patients in whom tumor ablation was incomplete underwent successful repeat RFA before entering the NED state. By using the model, we followed up with patients throughout the rest of their lifetime, with risks of events occurring monthly. Patients faced risks of death that were specific to their current health state. In addition, patients could have local progression, defined as progressive disease within or at the planning target volume margin for SBRT, or recurrence within or adjacent to the ablation zone for RFA (9). Those with local progression after SBRT or complete tumor ablation underwent retreatment with either SBRT or RFA within a month. A patient could undergo retreatment only once, because we defined distant or regional progression as having a second local progression or progressive disease elsewhere in or outside the liver. Table 1 lists model parameters and their sources.

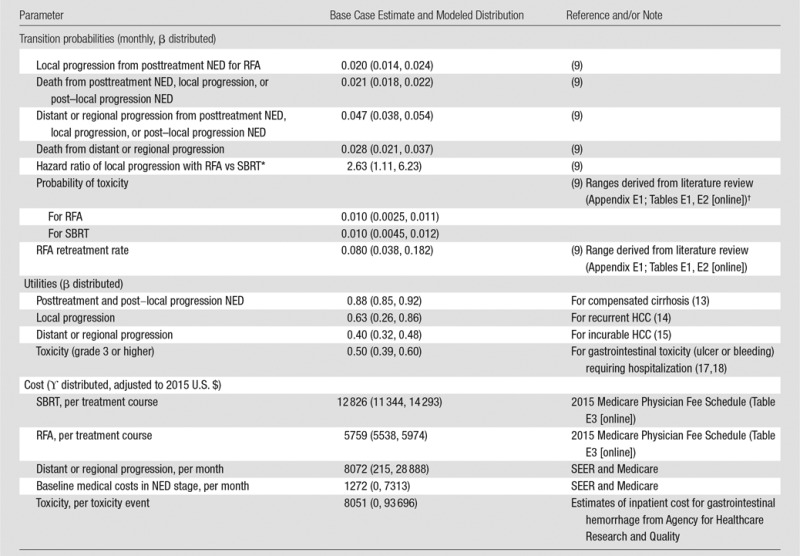

Table 1.

Model Input Parameters, Distributions, and Ranges

Note.—Data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. SEER = surveillance, epidemiology, and end results.

*Log-normal distribution.

†Assuming that these rates are the same at initial treatment and treatment for local progression.

Cancer Recurrence, Progression, and Mortality

Our base case analysis was an evaluation of a 60-year-old man with localized HCC who was not eligible for resection or transplantation, similar to patients in the Wahl et al study (9). The patients in the Wahl et al study were not surgical candidates and were eligible for local therapy with RFA or SBRT. The majority of patients in the Wahl et al study were male, with one to two lesions smaller than 3 cm, with Child-Pugh scores of A or B, and an average age of 60 years. We derived risks of local progression of cancer, distant or regional progression, and mortality for patients similar to those in the study. We calibrated the risks used in the model to those implied by in the study by using an iterative optimization algorithm that simultaneously minimized the sum of the square differences between model-simulated survival curves and all equivalent Kaplan-Meier curves from the study (Fig E1, Table E4 [online]) (11). For our base case, we assumed that local progression did not increase the probability of progression to distant or regional disease or death. We also performed a sensitivity analysis in which we recalibrated the model, allowing local progression to be associated with higher risk of progression to distant or regional disease and death than the NED state. To apply the calibrated risks to patients treated with SBRT, we assumed that overall survival and freedom from distant or regional progression were equal for SBRT and RFA and that, as observed in the study, the hazard ratio of local progression with RFA relative to SBRT was 2.63 (95% confidence interval: 1.11, 6.23) for all lesions (9).

Health-related Quality-of-Life and Toxicity

We expressed health-related quality of life as utility weights for each health state in the model. The utility weight of NED states (0.88) was the same as that used for compensated cirrhosis, and was based on EuroQol 5 dimensions, or EQ5D, index scores (12). The utility weights for locally recurrent and extensive HCC were the same as those in prior studies (13,14). We computed overall utility by multiplying the disease-specific utility weights by age-specific baseline utility weights (15).

Treatments can result in adverse events that reduce health-related quality of life. Instead of explicitly modeling each type of adverse event, we accounted for the overall effects of initial treatment and retreatment as a short-term disutility. We assumed that 10% of patients experienced toxicity from both SBRT and RFA (9), and there were no treatment-related deaths in our base case. We assumed the toxicity’s disutility to be similar to that of gastrointestinal toxicity (ulcer or bleeding) (16,17) requiring intervention or hospitalization, because this was the most common toxicity in Wahl et al (9). We assumed that the probability and disutility of toxicity with retreatment were the same as those of initial treatment. We established point estimates and uncertainty ranges for toxicity and retreatment rates by combining estimates from the literature (Appendix E1; Tables E1, E2 [online]).

Costs

The model included the costs of underlying health conditions and their treatments and toxicity. The SEER program and Medicare provided estimates for costs of distant and regional progression and the NED state in U.S. dollars (18). Both estimates were adjusted to account for increasing baseline medical costs with increasing age by using the medical expenditure panel survey household component, or MEPS, data (19). We estimated costs of SBRT and RFA by using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services physician fee schedule (20) (Table E3 [online]). We assumed that SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis with the radiation dose administered in five fractions without fiducial markers (21). We assumed that RFA is performed percutaneously with general anesthesia as an outpatient procedure and included payment classification for ambulatory procedures (22) and anesthesia costs. We accounted for repeat RFA ablation for incomplete tumor ablation (Table 1) in the initial cost of RFA. We assumed no retreatment for SBRT, because treatment efficacy cannot be evaluated immediately after radiation, and unsuccessful treatment with SBRT is counted instead as local progression. National average costs for inpatient treatment of gastrointestinal hemorrhage were a proxy for those for major events of toxicity (grade 3 and higher) (23). We did not consider costs for more minor events of toxicity, because these typically do not require substantial additional costs to address. For all costs, we adjusted published estimates used in our analysis to 2015 U.S. dollars by using data from the Consumer Price Index Health Care Services group.

Cost-effectiveness

We expressed lifetime health benefits that combined both morbidity and mortality in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) (24). Likewise, we tallied lifetime costs due to treatments, toxicity events, and underlying health conditions. We considered both benefits and costs from a societal perspective regardless of to whom they accrued and discounted both at a 3% annual rate. To assess cost-effectiveness, we considered the incremental costs and benefits of each of the four strategies relative to the next best, nondominated alternative by using incremental cost-effectiveness ratios. Dominated strategies are those that are more costly and less effective than alternative strategies. We assumed a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY gained.

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our results. One-way deterministic analyses were used throughout each parameter’s uncertainty range to examine how our results depended on each parameter separately. We used probabilistic sensitivity analysis with 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations to examine the effect of varying all parameters simultaneously on the basis of the proportion of simulations for which each strategy was optimal at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY. We produced joint uncertainty distributions for utilities for the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, respecting preference order and preserving each utility’s marginal distribution (Appendix E2 [online]). Appendix E3 (online) describes how we produced the joint uncertainty distributions of the probabilities of local progression, distant progression, and mortality.

Results

Health Benefits

Our model output reflected a median overall survival time of 24 months. SBRT-SBRT and SBRT-RFA both had a 1-year rate of freedom from local progression of 93.6% and 1-year rates of freedom from distant and regional progression of 57.9% and 57.7%, respectively. RFA-RFA and RFA-SBRT had a 1-year rate of freedom from local progression of 84.4%, and 1-year rates of freedom from distant and regional progression of 57.0% and 57.7%, respectively. When we considered both mortality and morbidity, we found that SBRT-SBRT yielded the most QALYs (1.565), while RFA-RFA yielded the fewest (1.546) (Table 2).

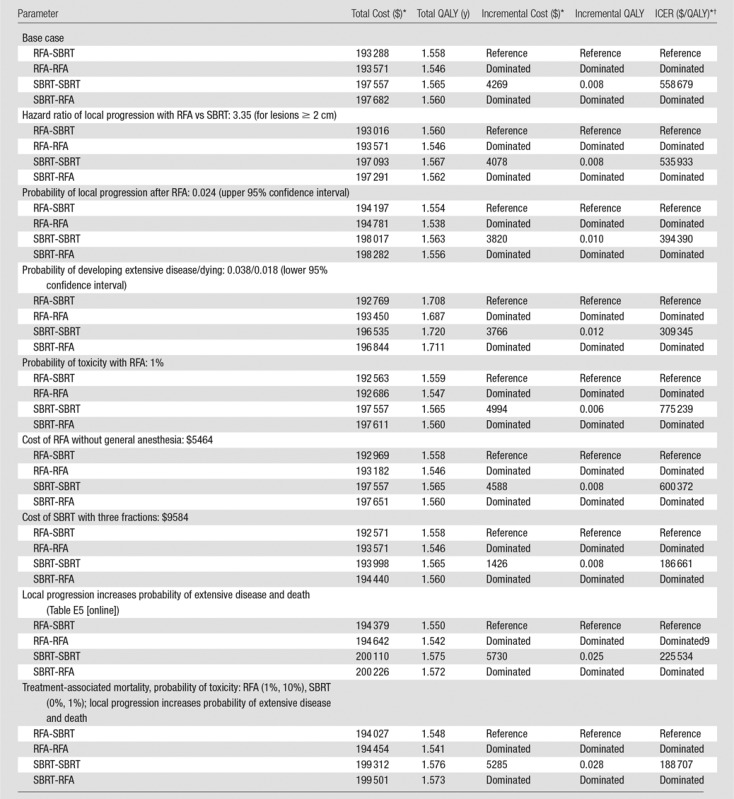

Table 2.

Base Case Analysis and Deterministic Sensitivity Analyses of Key Model Assumptions

*All costs are in U.S. dollars.

†ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

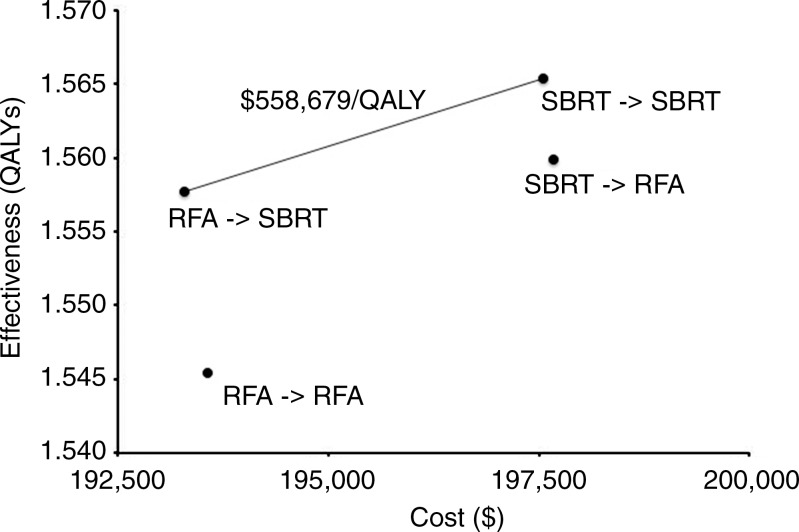

Costs and Cost-effectiveness

SBRT-RFA had the highest cost ($197 682), while RFA-SBRT had the lowest cost ($193 288). Considering health benefits and costs simultaneously, we found that SBRT-SBRT at a cost of $558 679 per QALY was not cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY (Table 2). RFA-RFA and SBRT-RFA were dominated strategies. Figure 2 shows the efficient frontier (ie, the set of nondominated strategies).

Figure 2:

Graph of efficient frontier shows cost-effectiveness of the four combinations of treatments.

Sensitivity Analysis

Table 2 shows the results of deterministic sensitivity analyses of parameters that would decrease the cost per QALY gained of SBRT-SBRT. If the hazard ratio of local progression with RFA versus SBRT was higher at 3.35 (for larger lesions [9]) or if the risk of death and extensive disease were lower (thus allowing the patient to benefit from a highly effective local treatment), SBRT-SBRT would still not be cost-effective with the assumption of a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY (Table 2).

We found that our assumption that local progression does not increase risk of developing extensive disease or dying would bias the results against SBRT being cost-effective, because SBRT is more effective at preventing local progression. We recalibrated the model, allowing local progression to be associated with increased risk of developing extensive disease or dying. By using the new point estimates from this calibration (Table E5 [online]), SBRT-SBRT still cost $188 707 per QALY gained relative to RFA-SBRT, and RFA-SBRT was still cost-effective, dominating both RFA-RFA and SBRT-RFA. If SBRT were cheaper and delivered in three fractions (25) rather than five, it would cost $186 661 per QALY gained relative to RFA-SBRT.

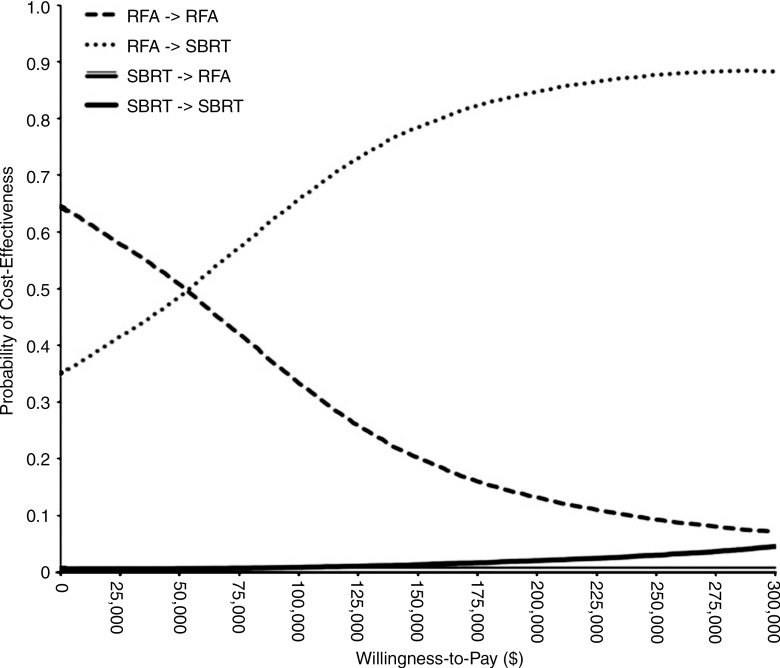

Given that RFA is operator dependent, we examined the effect of the risk of RFA complication, treatment-associated mortality, and treatment costs on our results. Because conscious sedation instead of general anesthesia is used for RFA at some institutions, we varied the cost of RFA to exclude the cost of general anesthesia. We also varied the risk of toxicity with RFA down to 1%. RFA-SBRT remained the most cost-effective strategy with these changes. We also examined the scenario that would most favor SBRT—if RFA had treatment-associated mortality of 1% (9,26,27) and risk of toxicity of 10%, while SBRT had no treatment-associated mortality and risk of toxicity of 1%, and local progression was associated with increased risk of developing extensive disease or dying—and found that our results were unchanged (Table 2). Probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY gained, SBRT-SBRT was preferred in 0.9% of simulations, RFA-SBRT was preferred in 65.8% of simulations, RFA-RFA was preferred in 33.3%, and SBRT-RFA was preferred in 0% (Fig 3).

Figure 3:

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves show the uncertainty associated with optimal treatment strategy for inoperable, localized HCC.

Discussion

With advances in radiation therapy, data (28) have demonstrated the efficacy of SBRT in treating liver tumors. As such, SBRT has become integrated into the treatment of HCC (29). Wahl et al (9) showed that SBRT improves local control relative to RFA, particularly for larger lesions. On the basis of currently available evidence, we found that SBRT for initial treatment of localized HCC, with repeat SBRT for local progression, costs $558 679 per QALY gained relative to RFA-SBRT and is therefore not cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000. RFA-SBRT was the preferred strategy at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per QALY gained in 65.8% of simulations. In our sensitivity analysis, we found that three-fraction SBRT cost $186 661 per QALY gained, which was still not cost-effective. These results are driven by our assumption that local progression can be salvaged easily (28) and is not associated with a prolonged detriment in quality of life. Thus, even though SBRT provides better local control, as shown in Wahl et al (9), the incremental health benefit of initial SBRT is very small compared with initial RFA with SBRT reserved for salvage, thus leading to the large cost per QALY gained. However, we found that when RFA treatment has failed, salvage SBRT is the more cost-effective strategy compared with salvage RFA. On the basis of these findings, we believe that a reasonable approach is to offer initial RFA for HCC, with SBRT offered for local treatment failure. Given the rapid adoption of SBRT for liver tumors, this analysis has important implications in the determination of treatment guidelines, and the choice of optimal treatment strategy should include consideration of both cost and treatment outcome.

These results were robust in sensitivity analyses in which we assessed on the basis of assumptions that were biased against SBRT-SBRT being cost-effective. We assumed that development of local progression does not increase the risk of distant or regional progression or death, and that SBRT and RFA had equal probability of toxicity (9). When we recalibrated the model to allow local progression to be associated with increased risk of distant or regional progression and death, SBRT-SBRT cost less per QALY gained, because SBRT is more effective at preventing local progression, but still, the strategy’s cost remained higher than $100 000 per QALY. Because SBRT is a noninvasive therapy and theoretically can be associated with fewer complications than RFA, we examined the most optimistic scenario for SBRT, in which SBRT had no treatment-associated mortality and only a 1% probability of toxicity, while RFA was associated with 1% probability of death and 10% probability of toxicity, and found that our conclusions were unchanged. Although we did not undertake a formal stratified analysis on the basis of tumor size, given lack of necessary data stratified by tumor size, the results of our sensitivity analyses suggest that SBRT-SBRT would still not be cost-effective in scenarios where SBRT may offer improved outcomes compared with RFA, such as for larger tumors, which are more likely to recur after RFA (8,30,31). In all evaluated scenarios, RFA-SBRT was the most cost-effective strategy.

Our study had limitations. We only considered RFA and SBRT in our treatment strategies. Although other ablative therapies include microwave ablation and cryoablation, these strategies have not demonstrated improved efficacy over RFA, which is the standard-of-care treatment for localized HCC. There is also growing interest in combining RFA with transarterial chemoembolization (32) and SBRT with sorafenib (22), but these are also emerging treatment strategies that have not been widely adopted. Transarterial chemoembolization alone is not an adequate ablative treatment for HCC, given its inferior local control (2-year local control of 18%–45%) (33,34). In addition, we did not consider adjuvant therapy with sorafenib, which is not currently the standard of care, given the recently published adjuvant sorafenib for HCC after resection or ablation, or STORM, trial that demonstrated no improvement in survival after resection or ablation for localized HCC (35). Thus, we assume that, as long as patients had localized disease, they would be treated with local therapy consisting of either RFA or SBRT. We assumed that patients who have extensive progression after initial local therapy with SBRT or RFA could undergo a variety of therapies including transarterial chemoembolization, sorafenib, and best supportive care, and we estimated these costs in aggregate by using published SEER and Medicare costs. Varying these costs did not affect our results in our sensitivity analysis. Another limitation are the data on which the model was based. The Wahl et al study was a single-institution retrospective investigation with a heterogeneous patient population. Although we have partially addressed this by exploring a broad range of assumptions in our sensitivity analysis, we acknowledge that the effectiveness of SBRT needs further validation by means of prospective, randomized studies. In addition, health-related quality of life for patients with HCC with various local therapies is an increasingly important end point for patients and providers but has been, thus far, to our knowledge, understudied. Cost-effectiveness studies of SBRT must eventually incorporate these data to accurately reflect the total effect of therapy on patients, and thus, comparative quality of life studies in which treatment modalities are compared are needed.

It is also important to note that our model included the assumption that both RFA and SBRT were feasible options as initial treatment. However, in clinical practice, there are many other factors that influence the choice of optimal therapy for patients with inoperable, localized HCC. For example, SBRT may be preferred for lesions that are not safely accessible with RFA, such as those near the liver dome or adjacent to visceral organs at the liver edge, or lesions near large blood vessels, which are associated with higher recurrence rates with RFA due to the “heat sink” effect. Although medical and anatomic factors are most important to determining the optimal treatment, our analysis can help to inform treatment choices when the clinical scenario suggests that both RFA and SBRT are reasonable local modalities.

In conclusion, RFA is more cost-effective than SBRT for initial treatment of inoperable, localized HCC, despite the high local control with SBRT that has been shown in studies to date; however, SBRT is cost-effective relative to RFA to salvage locally recurrent tumors after RFA. Given that fractionation schemes can have a significant effect on cost-effectiveness, further research is needed to determine if shorter fractionation schemes can be given safely and effectively.

Advances in Knowledge

■ The results of this cost-effectiveness analysis showed that stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as initial treatment followed by SBRT for local progression was not cost-effective for patients with localized hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), at $558 679 per quality-adjusted life year gained relative to the treatment strategy of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) followed by SBRT for local progression.

■ At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100 000 per quality-adjusted life year gained, RFA-SBRT was the preferred strategy in 65.8% of simulations.

■ RFA is more cost-effective than SBRT for initial treatment of inoperable, localized HCC.

■ However, SBRT is cost-effective relative to RFA to salvage locally recurrent tumors after RFA.

Implication for Patient Care

■ On the basis of our findings, we believe that a reasonable treatment approach for patients with localized HCC who are eligible for both RFA and SBRT is to offer initial RFA for HCC, with SBRT offered for local failure.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE

Received July 12, 2016; revision requested August 29; revision received September 8; accepted October 10; final version accepted October 17.

D.K.O. supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. E.L.P. supported by the National Institutes of Health (KL2 TR 001083). J.G.F. supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K01AG037593-01A1). E.L.P, B.Y.D. supported by the Henry S. Kaplan Research Fund, Department of Radiation Oncology, Stanford School of Medicine. E.L.P., M.G., D.M. supported by Stanford Society of Physician Scholars’ Grant, Stanford School of Medicine.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: E.L.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. B.Y.D. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.A.M. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.R.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.F. disclosed no relevant relationships. N.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. A.C.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.K.O. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.G.F. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.T.C. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- NED

- no evidence of disease

- QALY

- quality-adjusted life year

- RFA

- radiofrequency ablation

- SBRT

- stereotactic body radiation therapy

- SEER

- surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer 2001;94(2):153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64(1):9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer 2016;122(9):1312–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Smith BD, Liffmann DK, Ward JW. The cost-effectiveness, health benefits, and financial costs of new antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(2):157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denniston MM, Klevens RM, McQuillan GM, Jiles RB. Awareness of infection, knowledge of hepatitis C, and medical follow-up among individuals testing positive for hepatitis C: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2008. Hepatology 2012;55(6):1652–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56(4):908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truty MJ, Vauthey JN. Surgical resection of high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection, preoperative considerations, and operative technique. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17(5):1219–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzaferro V, Battiston C, Perrone S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation: a prospective study. Ann Surg 2004;240(5):900–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl DR, Stenmark MH, Tao Y, et al. Outcomes after stereotactic body radiotherapy or radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(5):452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen AB. Comparative effectiveness research in radiation oncology: assessing technology. Semin Radiat Oncol 2014;24(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durkee BY, Qian Y, Pollom EL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(9):902–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woo G, Tomlinson G, Yim C, et al. Health state utilities and quality of life in patients with hepatitis B. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26(7):445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim KC, Wang VW, Siddiqui FJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of liver resection versus transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Hepatology 2015;61(1):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cucchetti A, Piscaglia F, Cescon M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hepatic resection versus percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for early hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2013;59(2):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanmer J, Lawrence WF, Anderson JP, Kaplan RM, Fryback DG. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med Decis Making 2006;26(4):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegel BM, Targownik L, Dulai GS, Gralnek IM. The cost-effectiveness of cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors in the management of chronic arthritis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(10):795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oster G, Huse DM, Lacey MJ, Epstein AM. Cost-effectiveness of ticlopidine in preventing stroke in high-risk patients. Stroke 1994;25(6):1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White LA, Menzin J, Korn JR, Friedman M, Lang K, Ray S. Medical care costs and survival associated with hepatocellular carcinoma among the elderly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(5):547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Studdert DM, Farid MS, Bhattacharya J. Will divestment from employment-based health insurance save employers money? The case of state and local governments. J Empir Leg Stud 2015;12(3):343–394. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. Baltimore, Md: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.RTOG Foundation . RTOG 1112 Protocol Information: Randomized Phase III Study of Sorafenib versus Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy followed by Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. https://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?study=1112. Updated March 8, 2016. October 16, 2015.

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Hospital Outpatient PPS. Baltimore, Md: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) . National Statistics on All Stays. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Published 2013. December 19, 2015.

- 24.Gold MR. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andolino DL, Johnson CS, Maluccio M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81(4):e447–e453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulier S, Mulier P, Ni Y, et al. Complications of radiofrequency coagulation of liver tumours. Br J Surg 2002;89(10):1206–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livraghi T, Solbiati L, Meloni MF, Gazelle GS, Halpern EF, Goldberg SN. Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology 2003;226(2):441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bujold A, Massey CA, Kim JJ, et al. Sequential phase I and II trials of stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(13):1631–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein J, Dawson LA. Hepatocellular carcinoma radiation therapy: review of evidence and future opportunities. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;87(1):22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pompili M, Mirante VG, Rondinara G, et al. Percutaneous ablation procedures in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma submitted to liver transplantation: Assessment of efficacy at explant analysis and of safety for tumor recurrence. Liver Transpl 2005;11(9):1117–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, et al. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008;47(1):82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Chen MS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation with or without transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(4):426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapir E, Tao Y, Schipper M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy as an alternative to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Abstract #4087. Presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush DA, Smith JC, Slater JD, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing proton beam radiation therapy with transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of an interim analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;95(1):477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(13):1344–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.