ABSTRACT

Nineteen years after Lisa Timmons and Andy Fire first described RNA transfer from bacteria to C. elegans in an experimental setting48 the biologic role of this trans-kingdom RNA-based communication remains unknown. Here we summarize our current understanding on the mechanism and potential role of such social RNA.

KEYWORDS: Bacteria, C. elegans, environmental RNAi, mobile RNA

Introduction

Caenorhabditis elegans is a small (≈1 mm) free-living nematode found in microbe rich rotting fruits and vegetation in temperate climates. It was chosen by Sydney Brenner as a model organism due to its numerous advantages for genetics and cell biologic analysis. It is easy to maintain in the laboratory, living on a diet of Escherichia coli bacteria. It is a self-fertilizing hermaphrodite with a relatively short generation time (3 days), and a large brood size (≈300), facilitating the generation of large isogenic populations of worms. In addition, it is transparent, an advantage for microscopy and cell biology. Through the painstaking work of John Sulston, together with Robert Horvitz, the entire cell lineage from egg to adult was mapped, including the 302 neuron nervous system.44,45

Discovery of RNA interference (RNAi) in an animal

The use of RNA sequences which are complementary (antisense) to some region of the mRNA of a gene of interest, in hopes that through Watson-Crick base pairing, the 2 molcules will hybridize and lead to misregulation of the expression of that gene, was first described by Izant and Weintraub in 198419 as an alternative to classical genetic analysis of mutants. Antisense RNA continued to be developed and became a common tool in the molecular biology toolkit.8 However, antisense gene knockdowns were generally not robust, and the mechanism by which silencing occurred was not known. It was not until a decade later that the first tantalizing hints of the pathway, later to become known as the RNA interference, or RNAi pathway, were uncovered. In 1995, Guo and Kemphures, in an attempt to inject antisense RNA to knockdown par-1 in C. elegans, reported similar knockdown efficiency for both the antisense and the sense strands alone, as well as the co-injection of both the sense and antisense strands corresponding to the par-1 mRNA.15 While previous reports of so-called co-suppression, or quelling, had been reported in petunias,34 and in Neospora crassa,37 this was the first example in an animal, and the inspiration for the seminal work of Fire and Mello, who, in 1998, hypothesized that contaminants in the single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) preparation led to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and that these dsRNAs were responsible for the silencing. Their work showed that targets could be efficiently silenced by injection of dsRNAs with sequence complementarity to the target.9

RNAi mechanism in C. elegans

The RNAi pathway is used to regulate gene expression.11 The pathway begins with the processing of either an endogenously generated or an environmentally supplied dsRNA. The dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 interacts with the dsRNA and initiates cleavage of the RNA by the conserved endonuclease DCR-1.36,47 DCR-1 produces double stranded-short interfering RNAs (ds-siRNAs) which are subsequently loaded into the Argonaute protein RDE-1.14,53 The passenger strand is degraded and the remaining strand guides RDE-1 via Watson and Crick base pairing to a target mRNA.43 The mRNA-RDE-1 complex is thought to recruit the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) RRF-1 which leads to generation of secondary siRNAs.35,41 The secondary siRNAs are loaded into other proteins of the Argonaute family and initiate post-transcriptional gene silencing in the cytoplasm via mRNA degradation and co-transcriptional gene silencing in the nucleus via modification of the chromatin.12,13

Systemic and environmental RNAi

While it took many years for the details described above to be worked out, soon after RNAi was first described in 1998, Tabara and Mello showed that RNAi could be initiated by soaking worms in a solution of dsRNA,46 and Timmons and Fire demonstrated that by expressing dsRNAs in the E. coli food of C. elegans, silencing could be induced by feeding.49 This has become known as environmental RNAi. The RNAi by feeding technique was optimized a few years later, using RNase deficient bacteria,26 and a few years after that, the first genome wide RNAi screen was reported.25 In the intervening year, working to understand how dsRNA injected into one tissue could lead to silencing in other tissues, Winston and Hunter reported the results of the first genetic screens for this so-called systemic RNAi, uncovering systemic RNAi deficient (Sid) genes, including sid-1,51 which encodes a dsRNA specific trans-membrane channel.7 A second Sid protein, SID-2, which is a single pass trans-membrane protein, was found to be essential for environmental RNAi (See detailed review24). The systemic RNAi genes are distinct from the genes involved in the canonical RNAi pathway described above and are not required for RNAi itself. In other words, in the absence of systemic RNAi genes, silencing still occurs, but it is localized and must be initiated by endogenously produced or injected dsRNA. The genes involved in systemic RNAi can be divided into 2 classes. One set of genes are important for the uptake of dsRNA from the environment into the worm, while a second set of genes are important for the transport of RNA, which is already in the worm, from one tissue to another.

Environmental RNAi

In the current understanding of the environmental RNAi pathway, dsRNA from the environment is initially internalized from the gut lumen. Subsequently, the internalized dsRNA is either transported through the intestinal cell from the apical to the basal surface and released into the pseudocoelom, or is first released into the gut cytoplasm and from there exported into the pseudocoelom. The dsRNA is later imported into the recipient tissue, where it enters the RNAi pathway.24

SID-2

In C. elegans, the only known role of the single-pass trans-membrane protein SID-2 is the uptake of dsRNA from the environment into the gut (Fig. 1A). Sid-2 mutants do not show any sign of RNAi by feeding, but are able to down-regulate GFP in the body wall via pharyngeal expressed RNA hairpins which target GFP (hpGFP).52 Therefore SID-2 is not required for intercellular transport of RNA within a C. elegans. However, SID-2 is required for dsRNA uptake from the gut lumen into the worm as indicated by the failure to detect fluorescently labeled dsRNA inside sid-2 mutant worms after soaking.31 In addition, SID-2 localizes in the gut as indicated by expression analysis of SID-2::GFP fusion protein.52 Expression of sid-2 in a heterologous system showed specificity for the uptake of ≥ 50 bp dsRNA.31 These findings indicate SID-2s important role in environmental RNAi, and in the future, studies on naturally occurring RNA uptake should focus on dsRNA uptake in the gut. However, it cannot be ruled out that another mechanism of RNA uptake exists that does not require SID-2. Such a system would have different properties and if it exists, its function may be independent of the RNAi pathway. Here, we focus on the potential of environmental dsRNA as a mechanism of communication.

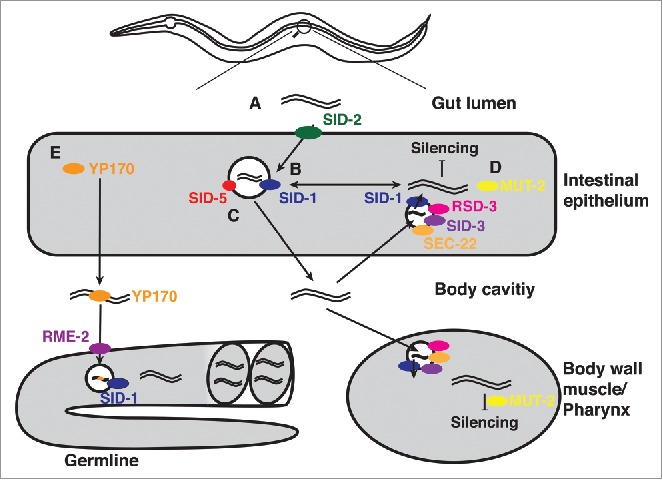

Figure 1.

Working model of the Sid pathway. (A) dsRNA is taken up via SID-2 mediated endocytosis from the gut into the intestinal epithelium. There are 2 competing theories for how the dsRNA exits the vesicle. (B) First is immediate exit into the cytoplasm via SID-1. (C) The second is that the dsRNA is transported via SID-5 through the membrane into the body cavity, and subsequently, re-enters the cell via a complex mechanism involving RSD-3, SID-3, SEC-22 and SID-1. (D) Once the dsRNA entered the cytoplasm silencing requires MUT-2. Additionally, MUT-2 has been proposed to have a role in the Sid pathway. MUT-2 may also mark dsRNA within a cell for export. (E) In the germline, an additional mechanism of RNA import exists. Genetic evidence demonstrates that dsRNA enters via the RME-2 receptor. A described previously role of the receptor is the import of the intestinally expressed yolk protein YP170 from the body cavity. The main role of the yolk protein is the delivery of nutrients for the newly forming oocytes. Therefore, it can be speculated that dsRNA associates with YP170 in the body cavity and/or in the intestinal epithelium, which can lead to silencing in the germline and in the offspring via a SID-1 dependent mechanism.

Systemic RNAi

SID-1

The first gene identified to be important for dsRNA transport was sid-1.51 SID-1 is a multispan trans-membrane protein and putative dsRNA channel. Expression of a SID-1::GFP fusion protein showed localization at the plasma membrane of almost all C. elegans cells, but appeared to be excluded from most neurons.51 The use of sid-1 mutant worms expressing SID-1 in a mosaic fashion indicated that SID-1 is required for the import of mobile RNA (Fig. 1B).21,22 Recent experiments have shed further light on the precise mechanism of dsRNA import via SID-1. This year, Marré and colleagues showed that fluorescently labeled dsRNA enters a cell via RME-2 (Receptor Mediated Endocytosis), a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor superfamily, but that SID-1 is required for the release of the dsRNA into the cytoplasm (Fig. 1E).30 Work in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells indicated that SID-1 enhances the uptake of dsRNA longer than 50 bp, but that complete sequence complementarity is not required. Thus primary miRNAs, which include a hairpin, can potentially be transported by SID-1.42 Surprisingly, neurons are deficient in RNAi by feeding, however overexpression of SID-1 from a neuronal promoter renders these cells RNAi competent indicating that SID-1 is required to take up dsRNA into neurons.4 These findings suggest that naturally occurring dsRNA can regulate the function of most tissues except for neurons. Therefore, an environmental dsRNA can have a systemic effect on gene expression or even a transgenerational effect via the germline. Current evidence suggests that SID-1 and SID-2 have similar physical requirements for the transport of RNA.

SID-3

SID-3 is a conserved tyrosine kinase required for the import of mobile RNAs (Fig. 1C).23 SID-3 is expressed in many tissues in the cytoplasm in punctuated foci as indicated by the analysis of the expression of sid-3::gfp and sid- 3::mCherry transgenes. It is speculated that these foci are related to endocytosis, since the human homolog of SID-3, the activated CDC42-associated kinase (ACK) localizes to endocytic vesicles.16 The use of sid-3 mutant worms with tissue specific rescue of sid-3 revealed that SID-3 is required for the import of mobile RNA.23 It is believed that SID-3 is an important protein in a signaling pathway for efficient RNA import, since the human CDC42 is implicated in many signaling pathways.32 Interestingly, in the absence of SID-3, local RNAi is enhanced.

SID-5

SID-5 is a predicted single-pass trans membrane protein important for efficient systemic RNAi. SID-5 is an important member of the pathway because it links RNA mobility to vesicle transport. Reports previously indicated that endosomal proteins are required for efficient RNAi but not for RNA mobility.28 SID-5 is the first protein of the Sid-pathway, which co-localizes with endosome markers and has a demonstrated role in RNA transport.17 SID-5 is required for RNAi in the gut via RNAi by feeding, suggesting that SID-5 has a similar role as SID-2. However, immunofluorescent stains show SID-5 expression in a range of tissues, in contrast to SID-2 which is expressed only in the gut. In addition, SID-5 is relevant for RNA silencing in the body wall muscle (bwm) initiated from the pharynx in contrast to SID-2. This indicates that SID-5 has a different role than SID-2. In addition, SID-5s role must differ from the role of SID-1 and SID-3, as a rescue of sid-5 in the recipient tissue (bwm) does not restore RNA silencing.17 This indicates that it is important for the export of RNA (Fig. 1C). Further experiments are required to determine the exact role of SID-5 in the systemic RNAi pathway.

SEC-22

SEC-22 is a SNARE (Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor) protein. SNAREs are a superfamily of proteins involved in membrane fusion and therefore important for vesicle trafficking.50 In C. elegans, SEC-22 suppresses small RNA mediated silencing in a sid-5 dependent manner. The use of sid-5 mutant worms with tissue specific rescue of sec-22 indicates that SEC-22 either inhibits trafficking or the RNAi machinery in the cell (Fig. 1C). In addition, mCherry::SEC-22 fusion proteins localize to the late endosome similar to SID-5. Furthermore, SEC-22 interacts with SID-5 in a yeast 2-hybrid system.54 Therefore, it is clear that SEC-22 is a negative regulator of RNAi and one may speculate that SEC-22 does so by promoting late endosome degradation. However, further experiments are required to untangle the role of SEC-22 in systemic RNAi or regulation of the RNAi factors within the cell.

RSD-3

RNAi spreading defective-3 (rsd-3) is required for RNA uptake in somatic and germline cells.18 Similar to SID-1 and SID-3, RSD-3 functions in RNA import (Fig. 1C). RSD-3 encodes for a homolog of epsinR and has a conserved ENTH (epsin N-terminal homology) domain. In mammalian systems, the ENTH domain is important for endomembrane trafficking.39 Interestingly, the ENTH domain of RSD-3 is sufficient in C. elegans for mobile RNAi. This suggests that the ENTH domain is able to mediate on its own downstream activities for RNA uptake or alternatively the ENTH domain is sufficient to down-regulate a RNA uptake suppressing signal. This provides another piece of evidence for the importance of the vesicle transport pathways for mobile RNA. Transgene expression experiments show that RSD-3 is expressed in many tissues and co-localizes with factors of the trans-Golgi network and the endosome.18 While the exact role of RSD-3 remains unclear, it is tempting to speculate about its role, and the role of its ENTH domain is to function as cargo adaptor. However, the ENTH domain has not been reported to bind RNA, therefore it is unlikely that RSD-3 directly interacts with RNA. More likely, the role of rsd-3 could be to sort other SID pathway members to their correct locations in vesicle trafficking.

MUT-2

Mut-2, known also as rde-3, is a putative nucleotidyltransferase important for mobile RNA. Mut-2 was first identified to play a role in transposon regulation.6 Subsequently, it became evident that mut-2 is essential for RNAi induced by feeding, but is not required for RNAi induced by transgene-driven expression of dsRNA.5 A more detailed analysis by 22 found that mut-2 is required for silencing by transgene-driven expression of dsRNA that is spatially separated from the tissue where the silencing occurs. Surprisingly, mut-2 can be rescued by the expression of mut-2 in only the tissue producing the mobile RNA (donor), or in only the tissue in which the silencing occurs (recipient). This indicates that mut-2 has a dual role (1) exporting the RNAi signal from the donor tissue, and (2) generating efficient RNAi in the recipient tissue (Fig. 1D). Therefore, in the donor tissue, the role of MUT-2 could be marking the mobile RNA by nucleotide addition for efficient export, and in the recipient, to generate efficiently the secondary siRNA.

Summary of environmental RNAi

Overall, environmental RNAi is an intriguing biologic process. In the last 20 years, we have gained insights into the mechanism via genetic analysis and have come to understand some of the physical requirements for RNA mobility in C. elegans. RNA transport is not as simple as diffusion and uptake in a recipient tissue. Many cellular processes, such as vesicle transport, are involved to regulate export and import of mobile RNAs. However, we still do not understand how RNA transport is regulated and how an RNA is chosen for delivery. Furthermore, our understanding of RNA transport remains very limited to its function in relation to RNAi, additional functions remain to be explored.

From artificial to natural context

RNAi by feeding has become a simple and powerful tool for the specific knockdown of genes. That it works so well, however, is intriguing because so far, it is only known in the artificial context of bacteria genetically engineered to express dsRNA with sequence complementarity to endogenous C. elegans genes. This leads one to speculate whether there may be a natural context in which the uptake of RNA for silencing may be important. While there are clear examples of trans-kingdom communication via RNA intermediates in a natural context, e.g. between humans and some of their parasites, and between plants and fungi,27 it is odd that no natural context has yet been discovered for C. elegans, where RNAi by feeding is such a powerful tool. Some recent experiments by Melo and Ruvkun may provide a conceptual bridge between artificial and natural RNAi by feeding. In these experiments, Melo and colleagues showed that E. coli artificially expressing dsRNAs against conserved genes in C. elegans could induce an avoidance response in the nematodes.33 The next step, then, was to look for naturally occurring RNAs in E. coli with sequence complementarity to C. elegans genes. Liu and colleagues reported on 2 such naturally occurring non-coding RNAs in E. coli, OxyS and DsrA, which have sequence complementarity to the C. elegans genes che-2 and F42G9.6, respectively.29 In these experiments, Liu et al. used a variety of behavioral and genetic techniques to assess whether these bacteria which had altered expression of these non-coding RNAs had any effect on C. elegans which fed on them. Their paper reports avoidance of E. coli over-expressing the OxyS ncRNA, as well as a variety of other chemosensory deficiencies in worms fed on OxyS expressing bacteria. Further, they report increased lifespan in worms fed on DsrA deficient bacteria. However, there is no direct evidence in this paper that these physiologic changes are the direct result of ingested ncRNAs, in fact, they show that these effects are still observed in mutants of sid-1 and sid-2, which are required for canonical environmental RNAi. In a follow up to this work, Akay and colleagues,1 showed that there is no activation of the canonical RNAi pathway by showing the absence of primary and secondary siRNAs mapping to the OxyS RNA via small RNA sequencing.

It is also important to note that E. coli is not a significant natural food source for C. elegans.38 In this paper, Samuel and colleagues collected likely C. elegans microbiomes from a variety of decaying vegetation in which these worms are often found. These were classified using 16S sequencing and, while no sequences matching Escherichia were found, many isolates contained other Enterobacteriaceae in low abundance. Samuel and colleagues also measure the time to adulthood of worms fed on different natural bacteria and found that the different bacteria can accelerate or delay development. In addition, they showed that the effect was not purely nutritional. While activation of pathogenicity responses to toxic bacteria are likely the cause of these effects, it will be interesting to see if environmental RNAi may also play a role.

It may be however, that despite the effectiveness of bacterially produced RNAs to silence C. elegans genes in the laboratory, that this simply does not occur naturally. It would require the co-evolution of the sequences across kingdoms, which, while not unprecedented, requires repeated interaction of the species over evolutionary time scales. One alternative may be that environmental RNAi is a mechanism of communication between worms. One could imagine that feeding on the corpses of worms from the previous generation could provide information via RNA which could be interpreted using the RNAi machinery. Interestingly, C. elegans, under stressful conditions such as starvation, exhibit a so-called bag-of-worms phenotype, where embryos hatch inside the cuticle of the mother20 This may provide one mechanism for the transmission of information vertically via environmental RNAi. One can speculate that this might be useful for relaying very recent information from the parental generation.

Initially proposed by Lisa Timmons and Andy Fire, environmental RNAi could also function in antiviral immunity.48 The recent discovery of a first C. elegans virus, the Orsay RNA virus, 10 allowed this to be tested. Indeed, C. elegans uses RNAi in antiviral defense 2,10 and delivery of dsRNA against the viral genome through bacterial feeding immunizes C. elegans against the virus.3 However, the generation of an antiviral RNAi response seems to be localized to the infected cells, with no evidence that it is either systemic or transgenerational.3

Perspectives

RNAi in C. elegans is potent and specific. Using sequence complementarity, information about a specific gene to silence is encoded into RNA molecules. A specific pathway exists for these molecules to be taken up from the environment and initiate systemic gene silencing. This system has a unique property in that it is a sort of universal translator. Any system capable of generating a dsRNA molecule can use this system as a communication channel. Thus, in contrast to a small molecule based system, which requires the evolution of a signaling pathway to respond to it, RNAi can be used to affect the expression of specific genes for which no pre-existing pathway yet exists. This system provides a way for information to be passed vertically, from one organism to its offspring, and horizontally, from the environment, and thus, in theory, between organisms.40 Furthermore, this provides a mechanism for information acquired from the environment of the parent to be transmitted and to influence the phenotype of the offspring. Physicist Murray Gell-Mann stated, regarding particle physics, that anything not forbidden is compulsory. Taking this to heart, surely inappropriately, we look forward to the first conclusive evidence of RNA mediated communication in a natural context in C. elegans. The questions to follow, such as when is RNA used as a signaling medium in contrast to other modalities, are surely to be of interest not just to RNA biologists, but to biologists in general.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Akay A, Sarkies P, Miska EA. E. coli OxyS non-coding RNA does not trigger RNAi in C. elegans. Sci Rep 2015; 5:9597; PMID:25873159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep09597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashe A, Bélicard T, Le Pen J, Sarkies P, Frézal L, Lehrbach NJ, Felix MA, Miska EA. A deletion polymorphism in the Caenorhabditis elegans RIG-I homolog disables viral RNA dicing and antiviral immunity. eLife 2013; 2, e00994; PMID:24137537; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.00994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashe A, Sarkies P, Le Pen J, Tnaguy M, Miska EA. Antiviral RNA interference against orsay virus is neither systemic nor transgenerational in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Virol 2015; 89:12035-46; PMID:26401037; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.03664-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calixto A, Chelur D, Topalidou I, Chen X, Chalfie M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat Methods 2010; 7(7):554-9; PMID:20512143; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CCG, Simard MJ, Tabara H, Brownell DR, McCollough JA, Mello CC. A Member of the Polymerase β Nucleotidyltransferase Superfamily Is Required for RNA Interference in C. elegans. 2005; PMID:15723801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JJ, Anderson P. The Tc5 family of transposable elements in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 1994; 137(3):771-81. PMID:8088523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2003; 301(5639):1545-7; PMID:12970568; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1087117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fire A, Albertson D, Harrison SW, Moerman DG. Production of antisense RNA leads to effective and specific inhibition of gene expression in C. elegans muscle. Development 1991; 113:503-14. PMID:1782862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998; 391(6669):806-11; PMID:9486653; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Félix M-A, Ashe A, Piffaretti J, Wu G, Nuez I, Bélicard T, Jiang Y, Zhao G, Franz CJ, Goldstein LD, et al.. Natural and Experimental Infection of Caenorhabditis Nematodes by Novel Viruses Related to Nodaviruses. PLoS Biol 2011; 9(1):e1000586; PMID:21283608; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grishok A. Biology and Mechanisms of Short RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. In Advances in Genetics, pp. 1-69. 2013; PMID:23890211; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-407675-4.00001-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guang S, Bochner AF, Pavelec DM, Burkhart KB, Harding S, Lachowiec J, Kennedy S. An argonaute transports sirnas from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Science (80-. ) 2008; 321:537-41; PMID:18653886; http://dx.doi.org/11486053 10.1126/science.1157647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guang S, Bochner AF, Burkhart KB, Burton N. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 2010; 293:2269-71; PMID:11486053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1062039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight SW, Bass BL. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 2001; 293:2269-71; PMID:11486053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1062039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo S, Kemphues KJ. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell 1995; 81(4):611-20; PMID:7758115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90082-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris KP, Tepass U. Cdc42 and vesicle trafficking in polarized cells. Traffic 2010; 11(10):1272-9; PMID:20633244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinas A, Wright AJ, Hunter CP. SID-5 is an endosome-associated protein required for efficient systemic RNAi in C. elegans. Curr Biol 2012; 22(20):1938-43; PMID:22981770; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imae R, Dejima K, Kage-Nakadai E, Arai H, Mi- tani S. Endomembrane-associated RSD-3 is important for RNAi induced by extracellular silencing RNA in both somatic and germ cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep 2016; 6:28198; PMID:27306325; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep28198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izant JG, Weintraub H. Inhibition of thymidine kinase gene expression by anti-sense RNA: A molecular approach to genetic analysis. Cell 1984; 36(4):1007-15; PMID:6323013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fay D. Genetic mapping and manipulation: Chapter 1-Introduction and basics (February 17, 2006), WormBook , ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, doi/ 10.1895/wormbook.1.90.1PMID: 18050463; http://dx.doi.org/19168628 10.1895/wormbook.1.90.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jose AM, Smith JJ, Hunter CP. Export of RNA silencing from C. elegans tissues does not require the RNA channel SID-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009; 106(7):2283-8; PMID:19168628; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0809760106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jose AM, Garcia GA, Hunter CP. Two classes of silencing RNAs move between Caenorhabditis elegans tissues. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18:1184-8; PMID:21984186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jose AM, Kim YA, Leal-Ekman S, Hunter CP. Conserved tyrosine kinase promotes the import of silencing RNA into Caenorhabditis elegans cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109(36):14520-5; PMID:22912399; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1201153109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose AM. Movement of regulatory RNA between animal cells. Genesis (New York, N.Y. : 2000) 2015; 53(7):395-416; PMID:26138457; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/dvg.22871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2003; 30(4):313-21; PMID:12828945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, Ahringer J. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol, 2000; 2(1):research0002.1; PMID:1117827; http://dx.doi.org/25188222 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knip M, Constantin ME, Thordal-Christensen H. Trans-kingdom cross-talk: Small RNAs on the move. PLoS Genet 2014; 10(9):e1004602; PMID:25188222; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YS, Pressman S, Andress AP, Kim K, White JL, Cassidy JJ, Li X, Lubell K, Lim DH, Cho IS, et al.. Silencing by small RNAs is linked to endosomal trafficking. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11:1150-6; PMID:19684574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Wang X, Wang HD, Wu J, Ren J, Meng L, Wu Q, Dong H, Wu J, Kao TY, et al.. Escherichia coli noncoding RNAs can affect gene expression and physiology of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun, 2012; 3:1073; PMID:23011127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms2071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marré J, Traver EC, Jose AM. Extracellular RNA is transported from one generation to the next in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113(44):12496-501; PMID:27791108; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1608959113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEwan DL, Weisman AS, Hunter CP. Uptake of extracellular double-stranded RNA by SID-2. Mol. Cell 2012; 47:746-54; PMID:22902558; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melendez J, Grogg M, Zheng Y. Signaling role of Cdc42 in regulating mammalian physiology. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:2375-81; PMID:21115489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.R110.200329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melo J, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen and xenobiotic associated defenses. Cell 2012; 149(2):425-66; PMID:22464749; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R. Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell Online 1990; 2(4):279-89; PMID: 12354959; http://dx.doi.org/16603715 10.1105/tpc.2.4.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pak J, Fire A. Distinct Populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science (80-. ) 2007; 315:241-4; PMID: 17124291; http://dx.doi.org/16603715 10.1126/science.1132839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker GS, Eckert DM, Bass BL. RDE-4 preferentially binds long dsRNA and its dimerization is necessary for cleavage of dsRNA to siRNA. RNA 2006; 12:807-18; PMID:16603715; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2338706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romano N, Macino G. Quelling: transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol Microbiol 1992; 6(22):3343-53; PMID:1484489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuel BS, Rowedder H, Braendle C, Félix MA, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans responses to bacteria from its natural habitats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113(27):3941-9; PMID: 27317746; http://dx.doi.org/15068792 10.1073/pnas.1607183113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saint-Pol A, Yélamos B, Amessou M, Mills IG, Dugast M, Tenza D, Schu P, Antony C, McMahon HT, Lamaze C, et al.. Clathrin adaptor epsinR is required for retrograde sorting on early endosomal membranes. Dev Cell 2004; 6:525-38; PMID:15068792; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00100-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkies P, Miska EA. Is There Social RNA? Science 2013; 341(6145):467-8;PMID:23908213;http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1243175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sijen T, Steiner FA, Thijssen KL, Plasterk RHA. Secondary siRNAs result from unprimed RNA synthesis and form a distinct class. Science (80-. ) 2007; 315:244-7; PMID: 17158288; http://dx.doi.org/21474576 10.1126/science.1136699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shih JD, Hunter CP. SID-1 is a dsRNA-selective dsRNA-gated channel. RNA 2011; 17(6):1057-65; PMID:21474576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2596511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiner FA, Okihara KL, Hoogstrate SW, Sijen T, Ketting RF. RDE-1 slicer activity is required only for passenger-strand cleavage during RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16:207-11; PMID:19151723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulston J, Horvitz R. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol, 1977; 56(1):110-56; PMID:838129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sulston J. Post-embryonic development in the ventral cord of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1976; 275(938):287-97; PMID:8804; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rstb.1976.0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabara H, Grishok A, Mello C. RNAi in C. elegans: soaking in the genome sequence. Science, 1998; 282(5388):430-1; PMID:9841401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.282.5388.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabara H, Yigit E, Siomi H, Mello CC. The dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 interacts with RDE-1, DCR-1, and a DExH-box helicase to direct RNAi in C. elegans. Cell 2002; 109:861-71; PMID:12110183; http://dx.doi.org/9804418 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00793-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 1998; 395(6705):854-4; PMID:9804418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/27579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 2001; 263(1-2):103-12; PMID:11223248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00579-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ungar D, Hughson FM. SNARE protein structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2003; 19:493-517; PMID:14570579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.155609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 2002; 295(5564):2456-9; PMID:11834782; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1068836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winston WM, Sutherlin M, Wright AJ, Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Caenorhabditis elegans SID-2 is required for environmental RNA interference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:10565-70; PMID:17563372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611282104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yigit E, Batista PJ, Bei Y, Pang KM, Chen C-CG, Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L, Mitani S, Simard MJ, Mello CC. Analysis of the C. elegans argonaute family reveals that distinct argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell 2006; 127:747-57; PMID:17110334; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao Y, Holmgren BT, Hinas A. The conserved SNARE SEC-22 localizes to late endosomes and negatively regulates RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA 2017; 23, 297-307; PMID: 27974622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.058438.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]