Introduction

The United States is currently in the midst of an opioid epidemic; in 2014, 2.9 million people reported non-medical use of opioid pain relievers, and 435,000 people used heroin.1 Correspondingly, a sharp increase in opioid overdose deaths, and emergency room visits has been reported in the past decade.2 Increased availability of illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids has contributed to sharp rises in “prescription opioid” deaths, since illicit fentanyl cannot be distinguished from prescription fentanyl on death certificates.3 An extended-release, injectable form of naltrexone (XR-naltrexone; VIVITROL®), is FDA-approved for relapse prevention following opioid detoxification.4,5 However, a substantial barrier to its effective implementation is the need to detoxify patients from opioids prior to initiation of naltrexone. The official prescribing information5 recommends that individuals abstain from opioids for 7–10 days prior to XR-naltrexone injection to avoid precipitated withdrawal. This waiting period, combined with conventional methods of opioid detoxification employing agonist tapers over several days, represents a delay of 2 weeks or more before XR-naltrexone can be administered. This is feasible during an extended residential treatment stay; however, availability of inpatient detoxification beds is decreasing and patients are seeking treatment in an outpatient setting.6 Unfortunately, outpatient opioid detoxification with traditional agonist taper is associated with significant attrition and high relapse rates6–9 resulting from craving for opioids,10 withdrawal symptoms11 and the delay to initiate XR-naltrexone following detoxification. Thus, new outpatient methods are needed to foreshorten the delay to injection naltrexone induction.

Various detoxification regimens including opioid antagonists have been first proposed in the 1980s to accelerate transition to treatment with naltrexone.12–17 Common to many is initiation of oral naltrexone at low doses and a gradual dose increase along with non-opioid ancillary medications to alleviate withdrawal symptoms that might be precipitated with naltrexone. Safe transition from opioid agonists to naltrexone in one week has been demonstrated.15,18–19 In earlier trials over the past two decades,14,16,20–25 we have developed and modified a 7-day detoxification regimen combining low doses of oral naltrexone with single-day buprenorphine and standing ancillary medications. Recently, Mannelli and colleagues, building on prior animal26 and human work27,28 on opioid detoxification, conducted a pilot study with simultaneous administration of buprenorphine and very low doses of oral naltrexone to initiate XR-naltrexone in an outpatient setting.29 However, to our knowledge no controlled trials have compared accelerated detoxification methods with a more standard taper of methadone or buprenorphine, followed by 7–10 days of wait period as recommended by the official Prescribing Information for XR-naltrexone.30

We conducted a randomized trial among participants seeking treatment for heroin or prescription opioid dependence, comparing two outpatient regimens: 1) Rapid induction consisting of single-day of buprenorphine administration followed by ascending doses of oral naltrexone (naltrexone-assisted detoxification) plus non-opioid ancillary medications versus 2) Standard 7-day buprenorphine taper followed by a 7-day delay to first XR-naltrexone dose (buprenorphine-assisted detoxification). We hypothesized that participants assigned to naltrexone-assisted detoxification would have a higher proportion of XR-naltrexone induction compared to those undergoing buprenorphine-assisted detoxification. We also hypothesized that episodes of severe withdrawal would be more frequent in the rapid induction group.

Methods

2.1 Participants

Opioid-dependent individuals seeking treatment were evaluated at an outpatient research clinic using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) (DSM-IV31) and a clinical interview assessing substance abuse severity. Medical evaluation included history, laboratory tests, electrocardiogram and physical exam. The Institutional Review Board of New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

The target enrollment was 150 participants who met DSM-IV criteria for current opioid dependence of at least six months duration and were able to give informed consent. Individuals with unstable medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included: 1) physiological dependence on alcohol or sedative-hypnotics; 2) history of accidental opioid overdose within past 3 years; 3) treatment with opioids for chronic pain; and 4) regular use of methadone or buprenorphine.

2.2 Study Procedures

Randomization

Participants were randomized on Day 1 to naltrexone-assisted detoxification or buprenorphine-assisted detoxification treatment arm in an open-label, parallel-group, outpatient clinical trial. Randomizations were carried out by a staff statistician not involved in the study. Participants were stratified by severity of opioid dependence: low-use stratum: ≤5 bags per day or ≤200 mg of morphine equivalents, and high-use stratum: >5 bags per day or >200 mg of morphine equivalents because baseline severity has predicted successful naltrexone induction in previous studies.21,32 Within each stratum participants were randomized 2:1 to naltrexone detoxification (n=98) or buprenorphine detoxification (n=52) to afford increased opportunity to examine safety and efficacy of the naltrexone-assisted regimen.

Detoxification Protocols

Study medications (buprenorphine, naltrexone, adjuvant medications) were administered on site in an open-label manner, and daily take-home doses dispensed as needed during the detoxification week. In both outpatient treatment arms, participants were assessed daily Monday–Friday in Days 1–8 for substance use, vital signs, withdrawal symptoms, and opioid craving. They were instructed to abstain from opioids for 12–24 hours prior to arriving at the clinic on Day 2 in mild-to-moderate withdrawal, measured using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale.33 Participants with score ≥6 received an initial buprenorphine dose of 2 mg; if well tolerated, subsequent 2-mg doses were administered every 1–2 hours, titrating up to a total dose of 8 mg.

Participants randomized to the naltrexone-assisted detoxification treatment arm followed a buprenorphine-clonidine-naltrexone procedure,12,22,34,35 as modified on the basis of our experience.14,16,20–25,32 On Day 3, participants began standing doses of clonidine (0.1–0.2 mg every 4 hours up to 1.2 mg) and clonazepam (1.0 mg every 6 hours up to 2 mg), which continued until Day 8. On Day 4, following pretreatment with prochlorperazine 10 mg, oral naltrexone was started at a dose of 1 mg, with additional doses given daily in ascending order (3 mg, 6 mg, 12 mg, 25 mg). On Day 8, having tolerated 25 mg naltrexone on the prior day, participants received an intramuscular injection (380 mg) of XR-naltrexone.

Participants randomized to buprenorphine-assisted detoxification received decreasing daily doses (8 mg to 1 mg) during Days 2–7, followed by a 7-day opioid washout period prior to XR-naltrexone administration on Day 15. Participants who completed the buprenorphine taper and remained in treatment for the subsequent 7 days were eligible for the naloxone challenge (0.8 mg), and if no withdrawal emerged they received an XR-naltrexone injection. Participants undergoing buprenorphine-assisted detoxification were not offered standing doses of adjuvant medications, but were given these if deemed clinically necessary.

Post-induction treatment phase

In both arms, participants received outpatient treatment for 4 weeks and those retained at Week 5 were offered an additional XR-naltrexone injection. Participants were offered adjuvant medications for one week following administration of XR-naltrexone to alleviate residual withdrawal symptoms. During each visit, on-site urine toxicology was performed for opioids, psychostimulants, and benzodiazepines; one sample weekly was sent to the laboratory for confirmation testing. Participants met weekly with a research psychiatrist to monitor treatment progress and review medication tolerability and adherence. All participants attended twice-weekly individual therapy sessions that included elements of Motivational Interviewing, Relapse Prevention, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.24,25 Participants were reimbursed for travel and assessments, up to a maximum of $680 potential earnings across the study.

Subsequently, participants were offered an extension phase of the study, during which referrals to continue treatment in community programs were initiated as deemed clinically appropriate and in accordance with the patient’s wishes.

2.3 Assessments and Data Analysis

The primary aims of this study were to (1) compare the odds of successful induction onto XR-naltrexone in participants across the two treatment arms; (2) compare the odds of second XR-naltrexone injection. Both primary outcomes were modeled using logistic regressions with main effects of treatment and adjusted by covariates: morphine equivalents of opioids being used at baseline, primary type of opioid use at baseline (heroin vs. prescription opioids), and route of opioid administration (intravenous [IV] vs. not IV). Dropout during detoxification or the post-induction phase was considered as failing to receive scheduled XR-naltrexone; dropout is a main failure mode in treatment of opioid dependence, most often accompanied by relapse to opioid use.

Secondary outcomes were: 1) successful completion of 8-day detoxification; 2) longitudinal daily presence of at least mild opiate withdrawal (mean Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale ≥ 5) during detoxification; 3) longitudinal daily presence of at least one report of moderate/severe withdrawal (maximum Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale ≥ 12) during detoxification; 4) longitudinal continuous measure of Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale during weeks 2 through 5 after XR-naltrexone induction; 5) longitudinal continuous measure of Hamilton Depression Rating Scale during weeks 2–5 after XR-naltrexone induction; and 6) successful 2-weeks abstinence (according to both urine and self-report) during weeks 4 and 5 after first XR-naltrexone dose.

Secondary outcomes 1) and 6) were analyzed using a logistic regression model similar to the primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes 2) – 5) were analyzed during the detoxification phase using longitudinal mixed effects models with either logit-link functions (outcomes 2) and 3)) or identity-link function (outcomes 4) and 5)). A random intercept was used to account for the between subject variances and for outcomes 4) and 5) an autoregressive (AR1) covariance structure was used to account for the correlation of the repeated observations within subjects over time. To define ‘time’ during detoxification for outcomes 2) and 3), the day corresponding to the outpatient opioid detoxification regimen assigned to either arm was used (see Table 1) and is referred to as the protocol day. This naming method ensured consistency in the dosing regimen across participants, as the protocol allowed a participant to complete a missed visit on the following day or to repeat a dose in case of opioid use. The two-way interaction between time and treatment was assessed first and retained in the final model if found significant. If no significant interaction between time and treatment was found, a model with main effects of time and treatment was fit while accounting for the same baseline covariates as used in primary outcome analyses, in addition to continuous Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Table 1.

Outpatient opioid detoxification regimen, by treatment arm

| Protocol Day | Naltrexone-assisted Detoxification | Buprenorphine-assisted Detoxification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ancillary medicationsa to support abstinence | |

| 2 | Buprenorphine 4 mg s.l. BID | |

| 3 | — (washout) | Buprenorphine 6 mg |

| 4 | Naltrexone 1 mg | Buprenorphine 4 mg |

| 5 | Naltrexone 3 mg | Buprenorphine 4 mg |

| 6 | Naltrexone12 mg | Buprenorphine 2 mg |

| 7 | Naltrexone 25 mg | Buprenorphine 1 mg |

| 8 | VIVITROL 380 mg IM | |

| 15 | VIVITROL 380 mg IM | |

Adjuvant medications offered included: clonidine 0.1mg QID (+ q 4 hrs PRN; maximum daily dose=1.2 mg), clonazepam 0.5 QID (MDD=2.0 mg), prochlorperazine 10mg TID, trazodone 100 mg HS, and zolpidem 10 mg HS.

PROC GLIMMIX and PROC LOGISTIC in SAS® 9.4 were used to conduct all analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided on level of significance of 5%.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Description

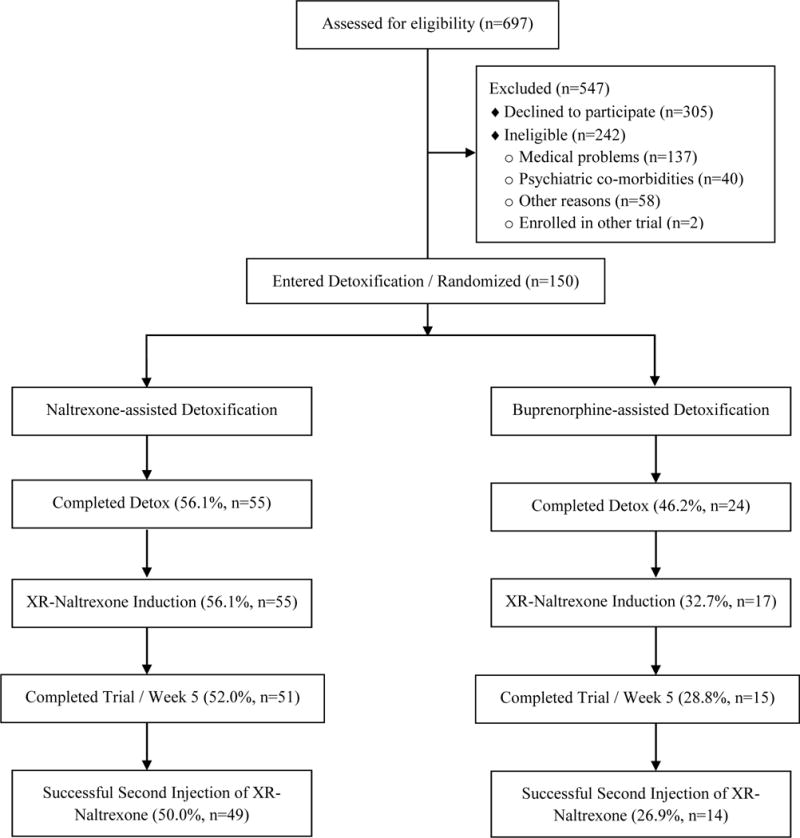

During the study, a total of 697 adults were assessed for eligibility (see Figure 1 for CONSORT diagram). The most common medical and psychiatric reasons for exclusion during screening were untreated hypertension (8), abnormal ECG (6), diabetes (6), and acute psychotic (17) or bipolar disorder (13). One hundred fifty participants were entered into the study and were stratified based on baseline level of opioid use: low-use stratum (≤5 bags per day or 200 mg of morphine equivalents or less, n=71) and high-use stratum (>5 bags or 200 mg per day, n=79). Demographic characteristics of the 150 randomized participants are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of participants in a controlled study of oral naltrexone vs. buprenorphine as detoxification strategies for induction onto extended-release naltrexone in opioid-dependent adults

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the participants randomized to outpatient detoxification with oral naltrexone or buprenorphine (N=150)

| Naltrexone-assisted

Detoxification (n=98) |

Buprenorphine-assisted

Detoxification (n= 52) |

Total (n= 150) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Female | 15 | 15.3 | 6 | 11.5 | 21 | 14.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 61 | 62.2 | 35 | 67.3 | 96 | 64.0 |

| Hispanic | 25 | 25.5 | 10 | 19.2 | 35 | 23.3 |

| African American | 8 | 8.2 | 5 | 9.6 | 13 | 8.7 |

| Asian | 2 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Native American | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Other | 2 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Route of opioid administration | ||||||

| Intranasal | 58 | 59.2 | 22 | 42.3 | 80 | 53.3 |

| Intravenous | 14 | 14.3 | 19 | 36.5 | 33 | 22.0 |

| Oral | 23 | 23.5 | 11 | 21.2 | 34 | 22.7 |

| Smoked | 3 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Primary type of opioid used at baseline (prescription users) | 35 | 35.7 | 20 | 38.5 | 55 | 36.7 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 35.2 | 11.8 | 35.1 | 10.9 | 35.2 | 11.4 |

| Severity of usea | ||||||

| Bags of heroin/day | 8.3 | 4.6 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 8.3 | 5.0 |

| mg morphine/day | 285.3 | 174.4 | 292.9 | 208.5 | 287.9 | 186.3 |

A “bag” was estimated to contain 10 mg of heroin, equivalent to 20 mg of morphine intranasally or 40 mg of morphine orally, the most common route of administration of prescription opioids.

3.2. Primary Outcome: Induction onto Injection Naltrexone

The primary outcome (1), successful induction onto XR-naltrexone, was achieved in 48.0% (n=72) of the 150 randomized participants: 56.1% (n=55) of naltrexone detoxification group vs. 32.7% (n=17) of buprenorphine detoxification group. The logistic regression model estimated a significant treatment effect (χ12=6.58, p=.010) while controlling for the covariates specified in Section 2.3; the odds of having a successful induction in the naltrexone detoxification group were 2.89 times the odds in the buprenorphine detoxification group. Among the covariates, primary type of opioid use was significantly related to successful induction onto XR-naltrexone (χ12=9.56, p=.002); prescription opioid users had 3.76 times the odds of successfully transitioning to XR-naltrexone, compared to heroin users. The rest of the covariates (morphine equivalents: χ12=1.49, p=.223; route of opioid administration: χ12=1.56, p=.211) were not significant.

The primary outcome (2), successful second XR-naltrexone injection at week 5, was achieved in 42% (n=63) of the 150 randomized participants (50.0%, n=49) of the naltrexone detoxification group vs. 26.9% (n=14) of the buprenorphine detoxification group or 87.5% of the 72 successfully inducted participants (89.1%, n=49) of the naltrexone detoxification group vs. 82.4% (n=14) of the buprenorphine detoxification group. The logistic regression model estimated a significant treatment effect (χ12=6.37, p=.012) while controlling for covariates specified in Section 2.3; the odds of having a successful second XR-naltrexone injection in the naltrexone detoxification group were 2.78 times the odds in the buprenorphine detoxification group. Among the covariates, primary type of opioid use was significant (χ12=4.21, p=.040); prescription opioid users had 2.31 times the odds of receiving a second injection compared to heroin users. Morphine equivalents (χ12=1.85, p=.174) and route of opioid administration (χ12=0.89, p=.345) were not significant.

3.3 Secondary Outcomes

Mild withdrawal outcome

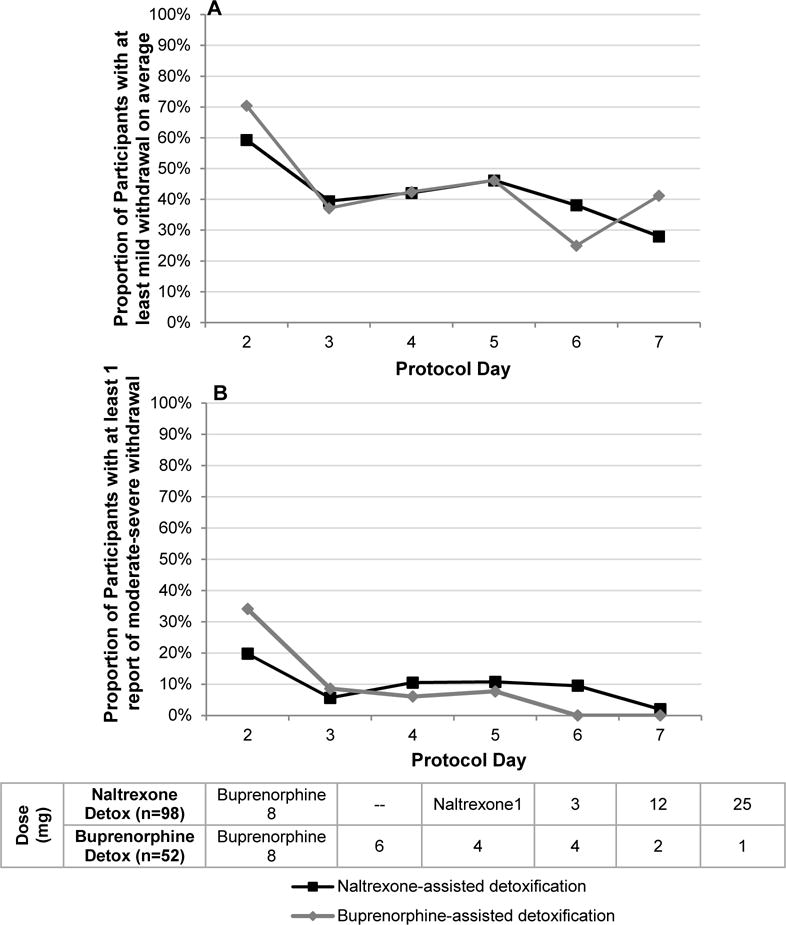

The observed proportions of participants with at least mild opiate withdrawal on average are displayed in Figure 2A. In the final main effects model, the daily proportion of at least mild opiate withdrawal on average, significantly decreased over time (F1,434=15.88, p< .0001) and was significantly positively associated with baseline Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (F1,434=4.28, p=.039) and morphine equivalents at baseline (F1,434=6.33, p=.012).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal observed daily proportion of participants with at least mild withdrawal on average (mean Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale ≥ 5), by treatment arm (Figure 2A); longitudinal observed daily proportion of participants with at least one report of moderate-severe withdrawal (maximum Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale ≥ 12) by treatment arm (Figure 2B).

Moderate/severe withdrawal outcome

The observed proportions of participants with at least one report of daily moderate/severe withdrawal are displayed in Figure 2B. The two-way interaction between treatment and protocol day was significant (F1,433=6.53, p=.011). Decrease in withdrawal scores was faster in the buprenorphine detoxification group compared to the naltrexone detoxification group, and the proportions of moderate to severe withdrawal were low and not significantly different between groups from days 2 to 5.

Successful completion of the 8-day detoxification phase

The proportions of participants who successfully completed the 8-day detoxification phase did not differ significantly (χ12=1.33, p=.250) by treatment: 56.1% (n=55) of the naltrexone-detoxification vs. 46.2% (n=24) of the buprenorphine-detoxification group. In the final main effects model, among the covariates, primary type of opioid use was significant (χ12=12.71, p=.001); prescription opioid users had 4.54 times the odds of successfully completing 8-day detox phase compared to heroin users.

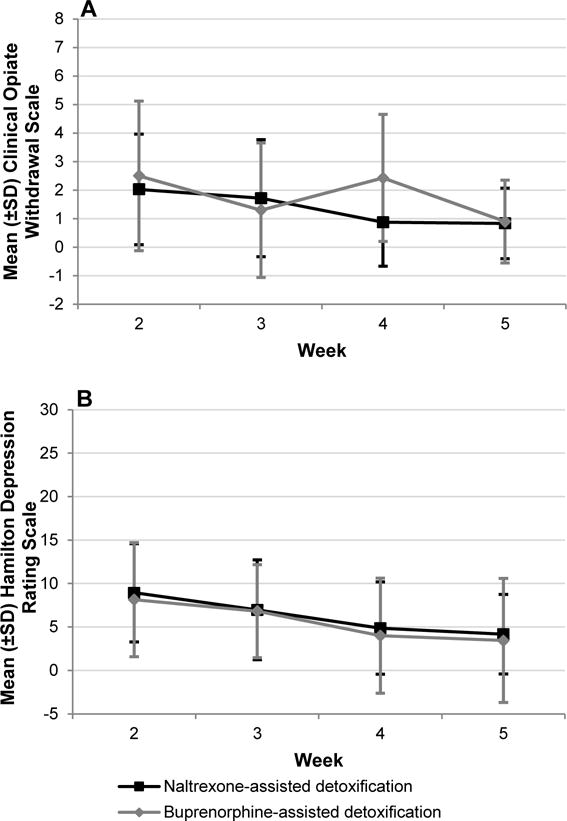

Withdrawal and Depression Scores during weeks 2 through 5 after XR-naltrexone induction (Figure 3A and 3B)

Figure 3.

Longitudinal Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (Figure 3A) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Figure 3B) scores during weeks after XR-naltrexone induction, by treatment arm.a

aError bars indicate standard deviation.

In the final main effects model, overall Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale and HAM-D scores did not differ significantly by treatment group (F1,112=0.32, p=.575; F1,121=0.05, p=.815, respectively). Following the XR-naltrexone injection, both Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores declined significantly from Week 2 to Week 5 for all participants (F3,112=6.25, p=.001; F3,121=10.75, p< .0001, respectively). Among covariates, the baseline withdrawal score was significantly positively associated with the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (F1,112=16.69, p< .0001) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (F3,121=10.75, p< .0001). At Week 2, the most commonly reported Hamilton Depression symptoms were early, middle and late insomnia. The most commonly reported Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale symptoms were anxiety/irritability, bone or joint aches, and tremor, and for Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale symptoms: feeling anxious, trouble sleeping, and feeling restless.

Two-week opioid abstinence during week 4 and 5 after XR-naltrexone induction

The overall proportion of continuous abstinence in participants successfully inducted onto XR-naltrexone was 80.6% (n=58) in Weeks 4–5 (78.2%, n=43) in the naltrexone detoxification group and 88.2% (n=15) in buprenorphine detoxification group). There was no significant effect of treatment (χ12=1.20, p=.274) as well as no significant effect of covariates.

3.4 Medication, Safety and Adverse Events

At least one adverse event was reported by 76.5% of the buprenorphine-detoxification group (n=13) and 55.6% of the naltrexone-detoxification group (n=30). None of the adverse events reported (see Table 3, Supplemental Data) was significantly different between treatment groups. Most were consistent with symptoms of protracted opioid withdrawal, occurring primarily during the first three weeks of treatment. None was sustained and none led to study discontinuation.

Table 3.

Adverse events reported by at least 5% of participants who completed detoxification (n=71)

| Naltrexone Detoxification (n=54) | Buprenorphine Detoxification (n=17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Adverse Event | n | % | n | % |

| At least 1 adverse event | 30 | 55.6% | 13 | 76.5% |

| Mood changes | 12 | 22.2% | 8 | 47.1% |

| Insomnia | 10 | 18.5% | 7 | 41.2% |

| Nausea/vomiting | 7 | 13.0% | 3 | 17.7% |

| Diarrhea | 7 | 13.0% | 1 | 5.9% |

| Bone/joint aches | 6 | 11.1% | 1 | 5.9% |

| Fatigue/drowsiness | 4 | 7.4% | 2 | 11.8% |

| Chills/cold sweats | 5 | 9.3% | 2 | 11.8% |

| Decreased appetite | 4 | 7.4% | 2 | 11.8% |

Two serious adverse events occurred in participants randomized to the naltrexone detoxification group, and neither was deemed study-related. A participant used heroin intravenously at the beginning of detoxification, prior to receiving any oral naltrexone, and was evaluated at an ER for cellulitis. Another participant was hospitalized one month post-XR-naltrexone for shortness of breath and chest pain, attributed to his misuse of phentermine the week prior to the SAE. No overdoses occurred among study participants. The New York State Psychiatric Institute IRB provided ongoing review of any adverse events.

4. Discussion

The aim of this randomized, controlled trial was to evaluate the relative efficacy of two methods of initiating treatment with XR-naltrexone in current opioid users in an outpatient setting. We found that participants undergoing a rapid 8-day, naltrexone-assisted treatment were significantly more likely to successfully initiate XR-naltrexone than participants assigned to the standard 15-day method including 7 days of buprenorphine-taper. Contrary to our expectations, severity of withdrawal and treatment dropout was comparable in both treatment arms during the first seven days of treatment. However, patients in the naltrexone-assisted detoxification group were able to receive naltrexone injection on Day 8, whereas participants in the buprenorphine-assisted detoxification group had to wait an additional 7 days, during which time 29% of participants who completed buprenorphine taper relapsed and were unable to receive naltrexone injection. Lower success rate in the buprenorphine-assisted detoxification group may be attributed primarily to the necessity for a waiting period between last dose of buprenorphine and the XR-naltrexone injection. Surprisingly, the severity of withdrawal symptoms was comparable during days 8–15 in both groups (post-buprenorphine discontinuation in buprenorphine-assisted detoxification group and post-naltrexone injection in naltrexone-assisted detoxification group). Safety data suggest that low-dose oral naltrexone is well tolerated in individuals with opioid use disorder transitioning to XR-naltrexone on an outpatient basis. Naltrexone-assisted detoxification was also associated with a significantly higher proportion of participants receiving a second XR-naltrexone injection in Week 5, further confirming that patients who received the first injection using the rapid method did not find this procedure aversive and accepted the subsequent injection.

The feasibility, tolerability and significant rates of success observed with rapid naltrexone induction are consistent with findings from a recent open-label outpatient study evaluating low-dose oral naltrexone, in combination with buprenorphine, to initiate treatment with XR-naltrexone.29 The current study demonstrates in a controlled trial the safety and superior efficacy of low-dose oral naltrexone-assisted detoxification, compared to the traditional clinical approach of a descending agonist taper for transition to XR-naltrexone. The primary advantage of the naltrexone-assisted method is circumventing the need for a waiting period for agonist washout prior to XR-naltrexone, during which there is a high risk of relapse. This accelerated transition increases the success rate of XR-naltrexone-induction and has the potential to decrease overdose following detoxification.8,36–38 Buprenorphine-maintained individuals seeking to transition off buprenorphine while reducing their risk for relapse represent another relevant clinical population for this ascending-dose oral naltrexone regimen. Two recent studies have examined transition from brief39 or maintenance40 buprenorphine to naltrexone, and this patient population will be an important focus for future studies.

For all retained participants, withdrawal severity decreased significantly with time across the detoxification period, and average withdrawal severity continued to decrease after injection naltrexone. Additionally, the severity of withdrawal, depressive symptomatology, and proportions of reported post-XR-naltrexone adverse events did not differ between the two treatment groups among retained participants. These findings contrast with the widely held perception that agonist tapers afford a more tolerable and therefore successful transition from opioid dependence. To the contrary, participants treated with low-dose naltrexone did not exhibit greater withdrawal severity and were more likely to receive XR-naltrexone. All side effects reported were consistent with mild opioid withdrawal, and none was unexpected or study medication-related.

Our findings support the conclusion that a 7-day opioid detoxification with gradually ascending doses of oral naltrexone is a well-tolerated outpatient procedure, with a success rate comparable to inpatient induction.12, 32,33 Higher success rates for naltrexone induction were seen in participants with primary prescription opioid abuse, typically reflecting a lower level of physical dependence. For heroin-using individuals with higher-severity opioid dependence, further work is needed to make rapid induction more feasible. This outpatient induction strategy may be improved by permitting more flexible oral naltrexone dosing and more rapid transition to XR-naltrexone, thus minimizing the risk of dropout.

Several potential limitations relate to our study. We chose an open-label pragmatic study design to evaluate regimens as these might be implemented in real-world practice. Using a masked design would have increased internal validity, but it would have been logistically awkward to endeavor to mask two such different conditions (e.g., use of double-dummy oral and sublingual medications; adding a placebo injection in each group to be given on Day 8 or 15). Moreover, administering a placebo-injection raises ethical concerns, as patients who falsely believe they have received active naltrexone may use opioids. Such use would not only “unmask” their condition but also put them at risk of relapse and overdose. Staff were trained and motivated to help all participants be inducted onto XR-naltrexone regardless of randomization assignment. The primary outcome in this study – whether or not injection naltrexone was received – is objective and was not subject to rater bias. In addition, the frequency and duration of patient visits exceeded that common in outpatient practice. Given the necessity for structured withdrawal assessments to guide oral naltrexone dosing, a schedule of daily visits during outpatient opioid detoxification is recommended. Subject payments may have encouraged study visit attendance across both groups. Finally, our use of low-dose oral naltrexone required a research pharmacy to compound these doses, which are not FDA-approved or commercially available.

In conclusion, these results support the feasibility of ascending low doses of oral naltrexone, in combination with an initial dose of buprenorphine and standing non-opioid ancillary medications, as an outpatient regimen for opioid detoxification and induction onto injection naltrexone. By circumventing the need for a protracted period of abstinence and mitigating the severity of withdrawal symptoms experienced during detoxification, this strategy has the potential to considerably increase patient acceptability of, and access to, antagonist therapy. The proposed regimen proved significantly more successful for individuals with dependence on prescription opioids. Future studies should include patients who have been maintained on buprenorphine and are interested in discontinuing it while reducing their risk for relapse.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Daniel Brooks and the staff of the STARS treatment program. Special thanks go to the patients who participated in the study.

Role of funding source

Funding for this study was provided by NIDA grant DA030484 (Dr. Sullivan) and K24 DA022412 (Dr. Nunes). MAS, AB, and KM were responsible for data collection and management. AG, CJC and MP were responsible for data analysis.

Dr. Sullivan received medication for this NIH-funded study through the Alkermes Investigator-Initiated Trial program while a full-time faculty member at Columbia University. Dr. Sullivan participated in the design, initiation, and conduct of this study while at Columbia. After becoming an employee of Alkermes, Dr. Sullivan participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation. Dr. Bisaga received honoraria, consultation fees and travel reimbursement for training, medical editing and market research from UN Office on Drugs and Crime, The Colombo Plan, Motive Medical Intelligence, Healthcare Research Consulting Group, Indivor for an unbranded educational activity, GLG Research Group, and Guidepoint Global, and he received medication, extended-release naltrexone, from Alkermes for NIH-funded research studies. Dr. Bisaga served as an unpaid consultant to Alkermes, Inc. Dr. Levin received medication for NIH-funded research studies from US World Meds and consulting fees from GW Pharmaceuticals and served on the advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company (2005–2007) and Shire (2005–2007). Dr. Nunes received medication or software for research studies from Alkermes, Reckitt-Benckiser, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, and HealthSim; devices under investigation and travel reimbursement from Brainsway; advisory board fees from Lilly and book royalties from Civic Research Institute.

Footnotes

Contributors

MAS, AB, EVN conceived the study design. MAS and AB wrote the protocol, supervised the study, and were responsible for patient care. FRL, KMC, and JJM participated in data collection and provided patient care. MAS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AG, CJC and MP wrote the statistical analyses and results sections. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to critically revising the paper, and all read and approved the final submission.

Disclosures

All remaining authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Contributor Information

Maria A. Sullivan, Alkermes, plc., 852 Winter Street, Waltham, Massachusetts 02451 Columbia University – Psychiatry, 1051 Riverside Drive Unit 120, New York, New York 10032.

Adam Bisaga, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University – Psychiatry, New York, New York; New York State Psychiatric Institute – Division on Substance Abuse, New York, New York.

Martina Pavlicova, Columbia University – Biostatistics, NY, New York.

C. Jean Choi, New York State Psychiatric Institute – Biostatistics, New York City, New York.

Kaitlyn Mishlen, New York State Psychiatric Institute – Substance Abuse, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, New York 10032.

Kenneth M. Carpenter, Columbia University – Psychiatry, New York, New York New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York.

Frances R. Levin, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York

Elias Dakwar, NYSPI/Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons – Psychiatry, 1051 Riverside Drive Unit 66, NY, New York 10032.

John J. Mariani, Columbia University – Psychiatry, New York, New York

Edward V. Nunes, Columbia University – Psychiatry, New York, New York New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York.

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50).Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed on April 24, 2016.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC – Prescription Painkiller Overdoses Policy Impact Brief – Home and Recreational Safety. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths – United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 64(50–51):1378–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Physicians Desk Reference. 2015 http://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/vivitrol?druglabelid=1199&id=2886.

- 6.Day E, Ison J, Strang J. Inpatient versus other settings for detoxification for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004580. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004580.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling W, Hillhouse M, Domier C, Doraimani G, Hunter J, Thomas C, Jenkins J, Hasson A, Annon J, Saxon A, Selzer J, Boverman J, Bilangi R. Buprenorphine tapering schedule and illicit opioid use. Addiction. 2009;104(2):256–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, Sonne SC, Ling W. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1238–1246. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen S, Hillhouse M, Thomas C, Hasson A, Ling W. A comparison of buprenorphine taper outcomes between prescription opioid and heroin users. J Addict Med. 2013;7(1):33–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318277e92e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenois F, Le MC, Cador M. The motivational component of withdrawal in opiate addiction: role of associative learning and aversive memory in opiate addiction from a behavioral, anatomical and functional perspective. Rev Neurosci. 2005;16:255–276. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2005.16.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Northrup TF, Stotts AL, Green C, Potter JS, Marino EN, Walker R, Weiss RD, Trivedi M. Opioid withdrawal, craving, and use during and after outpatient buprenorphine stabilization and taper: a discrete survival and growth mixture model. Addict Behav. 2015;41:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigmon SC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, O’Connor PG, Kosten T, Woody G. Opioid Detoxification and Naltrexone Induction Strategies: Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(3):187–99. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.653426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charney DS, Heninger GR, Kleber HD. The combined use of clonidine and naltrexone as a rapid, safe, and effective treatment of abrupt withdrawal from methadone. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(7):831–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.7.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins ED, Kleber HD, Whittington RA, Heitler NE. Anesthesia-assisted vs. buprenorphine- or clonidine-assisted heroin detoxification and naltrexone induction: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;294:909–913. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umbricht A, Montoya ID, Hoover DR, Demuth KL, Chiang CT, Preston KL. Naltrexone shortened opioid detoxification with buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;56:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan MA, Bisaga A, Glass A, Mishlen K, Pavlicova M, Carpenter KM, Mariani JJ, Levin FR, Nunes EV. Opioid use and dropout in patients receiving oral naltrexone with or without single administration of injection naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigmon SC, Dunn KE, Saulsgiver K, Patrick ME, Badger GJ, Heil SH, Brooklyn JR, Higgins ST. A randomized, double-blind evaluation of buprenorphine taper duration in primary prescription opioid abusers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1347–54. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pozzi G, Conte G, De Risio S. Combined use of trazodone-naltrexone versus clonidine-naltrexone in rapid withdrawal from methadone treatment. A comparative inpatient study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziaddini H, Nasirian M, Nakhaee N. A comparison of the efficacy of buprenorphine and clonidine in detoxification of heroin-dependents and the following maintenance treatment. Addict Health. 2010;2(1–2):18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Glass A, Mishlen K, Carpenter KM, Mariani JJ, Levin FR, Nunes EV. A placebo-controlled trial of memantine as an adjunct to injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(5):546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan MA, Rothenberg JL, Vosburg SK, Church SH, Feldman SJ, Epstein EM, Kleber HD, Nunes EV. Predictors of retention in naltrexone maintenance for opioid dependence: analysis of a stage I trial. Am J Addict. 2006;15(2):150–9. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Cheng WY, Carpenter KM, Mariani JJ, Levin FR, Raby WN, Nunes EV. A placebo-controlled trial of memantine as an adjunct to oral naltrexone for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1–2):e23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Glass A, Mishlen K, Pavlicova M, Haney M, Raby WN, Levin FR, Carpenter KM, Mariani JJ, Nunes EV. The effects of dronabinol during detoxification and initiation of treatment with extended release naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunes EV, Rothenberg JL, Sullivan MA, Carpenter KM, Kleber HD. Behavioral therapy to augment oral naltrexone for opioid dependence: a ceiling on effectiveness? Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32(4):503–17. doi: 10.1080/00952990600918973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothenberg JL, Sullivan MA, Church SH, Seracini A, Collins E, Kleber HD, Nunes EV. Behavioral naltrexone therapy: an integrated treatment for opiate dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23(4):351–60. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Peoples JF, Oropeza VC, Van Bockstaele EJ. Chronic very low dose naltrexone administration attenuates opioid withdrawal expression. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(4):261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Buonanno A, De Risio S. Use of very low-dose naltrexone during opiate detoxification. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(2):63–70. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannelli P, Patkar AA, Peindl K, Gorelick DA, Wu LT, Gottheil E. Very low dose naltrexone addition in opioid detoxification: a randomized, controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2009;14(2):204–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mannelli P, Wu LT, Peindl KS, Swartz MS, Woody GE. Extended release naltrexone injection is performed in the majority of opioid dependent patients receiving outpatient induction: A very low dose naltrexone and buprenorphine open label trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;38:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Food and Drug Administration. 2015 Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021897s029lbl.pdf. Accessed on April 25, 2015.

- 31.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mogali S, Khan NA, Drill ES, Pavlicova M, Sullivan MA, Nunes E, Bisaga A. Baseline characteristics of patients predicting suitability for rapid naltrexone induction. Am J Addict. 2015;24(3):258–64. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosten TR, Morgan C, Kleber HD. Phase 2 clinical trials of buprenorphine: detoxification and induction onto naltrexone. NIDA Res Monogr. 1992;121:101–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Connor PG, Carroll KM, Shi JM, Schottenfeld RS, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Three methods of opioid detoxification in a primary care setting. A randomized trial. Ann Int Med. 1997;127(7):526–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-7-199710010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kakko J, Svanborg KD, Kreek MJ, Heilig M. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105:1545–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merrall EL, Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Mortality of those who attended drug services in Scotland 1996–2006: record-linkage study. Int Drug Policy. 2012;1:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sigmon SC, Dunn KE, Saulsgiver K, Patrick ME, Badger GJ, Heil SH, Brooklyn JR, Higgins ST. A Randomized, Double-blind Evaluation of Buprenorphine Taper Duration in Primary Prescription Opioid Abusers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1347–1354. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dakwar E, Kleber HD. Naltrexone-facilitated buprenorphine discontinuation: a feasibility trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:60–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]