Abstract

The objective of this case series is to describe the procedure and outcomes of a multidisciplinary approach to vaginoplasty using autologous buccal mucosa fenestrated grafts in two patients with vaginal agenesis. This procedure resulted in anatomic success with a functional neovagina with good vaginal length and caliber and satisfactory sexual function capacity and well healed buccal mucosa. There were no complications and patients were satisfied with surgical results. We conclude that the use of a single fenestrated graft of autologous buccal mucosa is a simple, effective procedure for the treatment of vaginal agenesis that results in an optimally functioning neovagina with respect to vaginal length, caliber, and sexual capacity.

Keywords: neovagina, Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Vaginal agenesis, also known as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, is characterized by the congenital absence of the vagina usually presenting with primary amenorrhea. One of the goals of medical and surgical management is to construct a neovagina functional for sexual intercourse. Currently, there is no consensus on the best technique to achieve this objective [1]. Non-surgical management of self-dilation with progressive perineal dilation is encouraged as first-line therapy, as it is minimally invasive, is endorsed by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [2], and can be effective for many patients [3]. However, for patients in whom non-surgical treatment is unsuccessful, surgery to create a neovagina may be considered.

Several surgical techniques for vaginal agenesis include the Vecchietti technique [4,5], Davydov procedure [6], bowel vaginoplasty [7], and McIndoe vaginoplasty, the preferred method for most clinicians [8-10]. The Vecchietti procedure, or traction vaginoplasty, does not require extraneous tissue grafting and may be performed laparoscopically; however, the procedure carries potential complications related to traction threads placed in vesicorectal space and possible later vaginal prolapse [4,11]. The three-stage Davydov technique involves abdominal mobilization of peritoneum, attachment of the peritoneum to the vaginal introitus, and closure that sutures the top of the new vagina [12]. While the Davydov procedure is advantageous with respect to granulation and scarring in the neovagina, the neovaginal tissue lacks lubrication and the procedure carries the risk of bowel and bladder injury [11]. Bowel vaginoplasty typically uses sigmoid colon and provides lubricated tissue with an excellent blood supply; however, the procedure requires bowel anastomosis and has associated morbidity including significant vaginal discharge, postoperative ileus, bowel obstruction, bowel ulceration, risk of malignancy, and diversion colitis [11, 13-17].

The McIndoe procedure allows for a vaginal approach to create the neovagina. Various types of graft material have been used for the McIndoe technique including autologous skin grafts, typically from the buttocks or thigh [10], amnion [18-20], Interceed (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) [21], peritoneum (Davydov procedure) [12,13,22,23], autologous in vitro cultured vaginal tissue [24], and labial or gracilis myocutaneous flaps [25-28]. The most commonly used graft material for the McIndoe procedure is split thickness skin graft obtained from the buttocks or thigh area. Complications include scarring and contracture of the graft material, coloration and presence of hair in the vaginal graft tissue, and poor cosmetic appearance of the donor site. As such, alternative graft materials are needed to minimize these adverse effects.

Some promising results have been reported regarding the use of autologous buccal mucosa to form the neovagina since 2003 [29-32]. The advantages of using buccal tissue include secretory capacity, hairless texture, coloration similar to native vaginal tissue, distensibility, and inconspicuous scarring at the donor site [29]. Microscopically, buccal and vaginal epithelium are histologically similar, both with mucus secretions [29]. Concerns have been raised that the size of the tissue obtained from the buccal region may be small relative to the surface area of the neovaginal cavity. Techniques described include mincing the buccal mucosa tissue obtained and applying it directly to the dissected neovagina space [31,32] and use of the whole fenestrated buccal graft [29,30,33,34]. Although many pediatric urologists are familiar with the technique of harvesting buccal mucosa [34], most gynecologists are not. Thus, oral maxillofacial surgeons are ideal collaborators for buccal graft harvest. As use of autologous fenestrated buccal mucosa graft for creation of a total neovagina is a novel technique with many advantages over more traditional methods, our aim was to describe our experience and outcomes using a multidisciplinary team approach in two patients with vaginal agenesis.

Case Summaries

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania reviewed this work and deemed it exempt.

Patient 1

Patient 1 presented at age 15 with cyclic pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. She had normal external female genitalia, normal hymen, and a blind vaginal pouch. A pelvic magnetic resonance image noted an abnormal appearing uterus measuring 9.5 × 4.9 × 7.2 cm with distended endometrial canal and no clear normal cervical or vaginal tissue as is consistent with the diagnosis of MRKH syndrome. The patient was also noted to have a left hematosalpinx and a 9.2-cm endometrioma arising from the left ovary.

Kidneys were normal on ultrasound evaluation. Following extensive counseling with the patient and her parents regarding the loss of reproductive function and the risks and benefits of uterine-sparing approaches, a decision was made to proceed with total laparoscopic hysterectomy, left salpingectomy, and left ovarian cystectomy. Her pelvic pain improved following surgery. At age 18, the patient commenced self-dilation to lengthen the vagina, however made minimal progress over the next two years with the addition of only 1 cm of vaginal length. At age 22, frustrated by lack of progress of dilation, the patient desired surgical intervention. Owing to concern over scarring at the donor site, the patient declined the use of split thickness skin grafts. An autologous buccal mucosa graft was proposed as an alternative. The patient was seen preoperatively by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon and was noted to have bilateral buccal mucosa 5 cm in width and > 2 cm in length.

Patient 2

Patient 2 presented at age 14 for primary amenorrhea. She had normal development of secondary sexual characteristics and a blind vaginal pouch. She underwent laboratory testing that revealed normal gonadotropins, androgens, thyroid stimulating hormone, and prolactin. Pelvic and abdominal ultrasound demonstrated absent uterus and normal kidneys. Karyotype revealed 46XX, confirming the diagnosis of MRKH syndrome. At age 19, the patient initiated dilator therapy. Despite being very motivated, she was only able to lengthen the vagina to 2 cm after > 6 months of dilator use. At the age of 20, after discussing options of continuing dilation and surgical construction of a neovagina, the patient desired to proceed with vaginoplasty; autologous buccal mucosa was proposed as an alternative to split thickness skin graft.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Surgical preparation

Both patients were counseled regarding the risks and benefits of vaginoplasty including risk of injury to bowel and bladder, vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula formation, failure of graft tissue to take, contracture of graft, and need for continued dilation. In addition, both patients were counseled regarding the risks of buccal harvest including pain, bleeding, infection, delayed healing, damage to adjacent structures—specifically Stenson’s duct, and trismus (spasm of the jaw muscles). Both patients were given full bowel preparation with 17 grams of polyethylene glycol and a mineral oil enema the day before surgery. Patients were also prescribed 200 mg of pyridium the night before surgery and the morning of surgery to facilitate intraoperative identification of ureteral patency at cystoscopy. Two grams of cefazolin were given intravenously prior to surgery. After general nasal endotracheal anesthesia was induced, both patients were placed in dorsal lithotomy position and were prepped and draped for the gynecologic portion of the surgery. Both patients were also prepped and draped for the oral surgical procedure with a full head wrap, securing the nasal endotracheal tube. The gynecologic and oral maxillofacial surgical teams performed vaginal dissection and buccal harvest procedures simultaneously.

Harvest of buccal mucosa (donor tissue)

A moistened throat pack was placed in the patients’ posterior oropharynx. Using Bovie electrocautery (Bovie Medical Corporation, Purchase, NY), an incision was made in the buccal mucosa 1 cm from the commissure of the lip extending inferiorly 5 mm from the mucogingival junction in the mandible. This excision was carried posteriorly to the retromolar pad remaining about 5 mm from the pterygomandibular raphe. The incision was then extended superiorly to approximately 5 mm below Stensen’s duct. Using electrocautery, the mucosal flap was raised superficial to the buccinators, elevated out of the mouth and passed to the gynecologic team to prepare for implantation (Figure 1). The same procedure was performed on the contralateral buccal mucosa. Hemostasis was achieved and after harvest was complete, the oropharynx was irrigated. The buccal mucosal flaps were kept moist in warm saline until needed.

Figure 1.

Buccal mucosa donor site following harvest

Preparation of vaginal cavity

After Foley catheter placement and careful examination of the perineum and rectum, a 3-cm transverse incision was made with a scalpel between the rectum and vagina. Using careful, progressive, and meticulous blunt dissection and intermittent rectal exams to identify location of and avoid injury to rectal tissue, a neovaginal lumen was created without injury to the rectum or bladder. Hemostasis was maintained during dissection by cautery and sutures.

Preparation of the buccal mucosa

Preparation of the buccal mucosa graft was performed according to the technique described by Grimsby et al [33]. The buccal mucosa was defatted, then fenestrated sharply. Using a 15-blade scalpel, small incisions were made 1 to 2 mm apart throughout the tissue (Figure 2a). By fenestrating the tissue, the size of the buccal graft was increased. The two graft pieces were anastomosed with 4-0 chromic gut sutures to form a diamond (Figure 2b). Warm, sterile saline was used to prevent desiccation of the grafts.

Figure 2a.

Preparation of buccal mucosa graft. Left-prior to fenestration, Rightfollowing fenestration

Figure 2b.

Bilateral buccal mucosal grafts sewn together

Affixation of donor tissue to graft site

The buccal mucosa graft was folded in half along the suture line and placed in the neovaginal space. The sutured edge was placed at the apex of the vaginal space and affixed with interrupted 4-0 chromic gut sutures [34]. The rest of the graft was stretched to fill the dissected neovaginal space and was affixed to the side walls and the perineum. These sutures were free of tension, and the graft provided excellent coverage of the cavity (Figure 3). At the end of the procedure, vaginal length was approximately 5 cm with caliber of two fingerbreadths. After irrigation, a 60-mL silicone inflatable vaginal stent (Silimed, Sientra Inc., Goleta, CA) lubricated with triamcinolone 0.025% cream was placed in the neovagina to facilitate graft application to the vaginal cavity. The stent was silk-sutured to bilateral labia majora (Figure 4). Rectal exam confirmed no injury, and cystoscopy demonstrated flow of pyridium-stained urine from ureteral ostia. Operating time was 197 minutes for Patient 1 and 203 minutes for Patient 2, and estimated blood loss was less than 5 mL for each patient. No intraoperative complications were noted.

Figure 3.

Affixation of buccal graft to neocavity

Figure 4.

Vaginal mold held in place by silk suture

Postoperative Management

On postoperative day (POD) 1, both patients were advanced to normal diets. Normal saline rinses of the mucosa were performed for oral hygiene. From POD 1 to 5, the patients remained on strict bed rest with Foley catheters to minimize displacement of the vaginal stent and to prevent tearing of labial sutures. The patients were given daily senna (Purdue Pharma, Stamford CT) and had soft bowel movements while admitted. The perineal area was kept clean and dry with gauze fluffs held in place with underwear. The patients were given intravenous and oral narcotics for discomfort. No antibiotics were administered in the postoperative period. On POD 6, patients were taken back to the operating room for vaginal mold removal and assessment of graft adherence under monitored anesthesia care. Vaginal stents were removed and neovaginas irrigated and inspected (Figure 5). Grafts were intact with greater than 60% adherence in both patients. Patients had vaginal lengths of 6 to 8 cm with > 2 fingerbreadths of vaginal caliber. Cystourethroscopy was performed using a 70-degree rigid cystoscope that demonstrated normal bladder and urethra in both patients, with no injuries noted. Rectal exam was normal without hematomas or injury. Medium- to large-sized soft Milex® (CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT) vaginal-rectal dilator was placed in the neocavity with a sterile condom covering the dilator owing to its porous consistency (Figure 6). Each patient passed voiding trials that evening and was discharged to home on POD 7. They were instructed to wear the vaginal molds continuously for 12 weeks, then nightly until sexual activity was initiated. The mold was held in place with a pad and tight-fitting underwear. The mold could be removed and replaced for showering or for restroom use. Patients were instructed on reinsertion techniques: to lubricate the vaginal mold at reinsertion with triamcinolone once daily in order to decrease the incidence of granulation tissue formation [34] and water-based lubricant all other times.

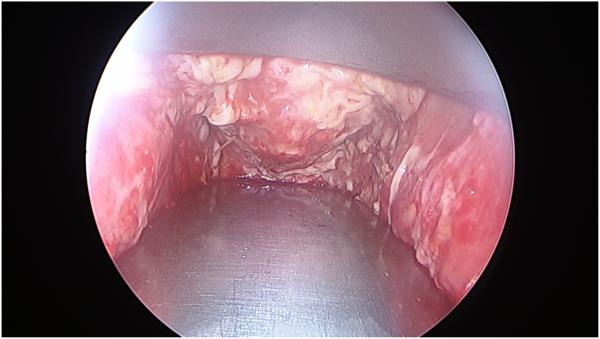

Figure 5.

Vaginal cavity on post-operative day #6 following stent removal

Figure 6.

Vaginal dilator placed into neocavity after removal of stent

By week 8, oral surgical sites of patient 1 were noted to be well healed with mild scarring on the left buccal mucosa (Figure 7). At 9 weeks, she was well-healed and her vaginal mucosa appeared healthy, entirely engrafted without granulation or stenosis. No strictures were noted and the patient had excellent vaginal caliber (> 2 finger width) and depth (> 8 cm length). She had increased dilation to the largest dilator without difficulty. After 18 weeks, she had been sexually active twice without any difficulty.

Figure 7.

Appearance of buccal donor site at 8 weeks following harvest

The oral donor sites for patient 2 were completely healed by week 10, with some firm submucosal scar formation. However, she did report tightness with opening her mouth and left V3 paresthesia. Though her maximal interincisal opening was within normal range, given the patient’s perceived restricted mouth opening, triamcinolone injections to buccal scars were performed and buccal massage instructed. She tolerated dilation well and was able to accommodate the largest dilator by week 12. The patient attempted vaginal intercourse after 12 weeks with difficulty. Owing to minimal lubrication, her partner was unable to fully penetrate the neovagina.

DISCUSSION

This is the first published case report in the United States using a multidisciplinary approach to perform a vaginoplasty with single-fenestrated autologous buccal grafts in patients with vaginal agenesis. This procedure achieved neovaginal anatomic success using a simple surgical technique resulting in complete uptake of the donor graft and good vaginal length and caliber. This was achieved with a 7-day hospitalization and 12-week stent duration, allowing for most recovery and rehabilitation to occur with ease in the patient’s home. By using a multidisciplinary approach, oral and gynecologic surgeries may be performed concurrently and facilitate an option for gynecologists not familiar with buccal mucosa grafts.

Vaginal reconstruction for MRKH using autologous buccal mucosa has been described in both animal and human models (Table 1) [29-32, 34-35]. The use of fenestrated autologous buccal mucosa was described by Yesim Ozgenel et al. [29] and Lin et al. [30]. Complications reported in these two reports included one bladder injury and one patient with vaginal bleeding. Grimsby et al. described the use of this technique in 7 patients (2 for secondary reoperations) [34]. Complications reported included a urethral injury, oral contracture, and reoperation. The use of “micromucosa” was described by both Zhao et al. [31] and Li et al. [32] where buccal grafts were first minced into < 1-mm pieces either using a microskin machine or by hand to increase the expansion ratio and edges for growth. These pieces were spread onto gelatin sponges and placed into the neocavity (mucosa facing the cavity) followed by a stent placed to hold the grafted pieces in place. There was a single report of vaginal bleeding from these reports.

Table 1.

Buccal mucosa for vaginal reconstruction for Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome

| Authors, year published |

Number of patients |

Donor tissue utilized | Outcomes discussed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yesim Ozgenel et al., 2003 (29) |

4 | Fenestrated autologous buccal mucosa |

Vaginal length 8-10 cm, depth 4-5 cm Fluid in cavity confirmed as mucus Satisfactory sexual intercourse in all patients (+lubrication, no dyspareunia) |

| Lin et al., 2003 (30) |

8 | Fenestrated autologous buccal mucosa |

Vaginal length 6-10 cm, 2 fingers in width |

| Zhao et al., 2009 (31) |

9 | Minced autologous buccal micromucosa |

Vaginal depth 6-10 cm in depth, 2 fingers in width 4/9 patients sexually active, 3 satisfied with sexual life |

| Li et al., 2014 (32) |

38 (4 with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome) |

Minced autologous buccal micromucosa |

Vaginal depth 7-10 cm Vaginal circumference 10-15 cm Mean volume 85-120 mL Man FSFI score 28.8 ± 2.1 Stent time 9-20 months |

| Grimsby & Baker, 2014 (34) |

7 (5 primary operations, 2 re- operations following prior vaginoplasties) |

Fenestrated autologous buccal mucosa |

5 patients with successful sexual activity with no dyspareunia (other 2 not yet sexually active) |

Our procedure was unique owing to the multidisciplinary approach with gynecologic and oral maxillofacial surgical teams. Simultaneous harvest of the buccal mucosa grafts and vaginal dissection by the respective surgical team minimized operative time. Cystoscopy and rectal exams confirmed no injury to bladder or rectum. Consideration could be made to perform a proctoscopy at the completion of the procedure to confirm rectal integrity. Graft uptake was complete in both patients at the time of first postoperative visit (approximately 2 weeks), with no evidence of graft infections. Epithelization was complete at 2 weeks, similar to previously described micromucosal graft techniques [32]. Both patients achieved improved and adequate vaginal lengths (5-10 cm) and calibers (2 fingerwidths), similar to that previously described [29-32, 34-35]. Each patient was able to use the largest size vaginal dilator by 12-weeks postoperatively, sizes that they were unable to accommodate prior to surgery.

Owing to short follow-up of the patients reported here, long-term sexual function following vaginoplasty with autologous buccal mucosa is unknown. One patient attempted vaginal intercourse unsuccessfully at 12-weeks postoperatively and continued to use vaginal dilators to lengthen the neovagina. Further, given limited sexual activity and use of lubricants, perceived lubrication provided by the neovagina itself could not be reported by the patients. The patients will need to be followed for longer periods of time to determine sexual function, satisfaction, and lubrication abilities. While maintenance of adequate vaginal length and caliber are needed for sexual intercourse, sexual satisfaction depends on other factors including psychological variables that must be taken into account [11]. As for the buccal donor site, both patients were able to resume a soft diet within 24 hours of surgery and tolerated a regular diet by the time of hospital discharge. Buccal mucosa donor sites healed well with minimal scarring in both patients. Owing to some restrictive symptoms for Patient 2, a steroid injection was performed with good results.

CONCLUSION

This case series confirms that the use of a multidisciplinary approach to create a neovagina using a single fenestrated graft of autologous buccal mucosa is a safe, effective, and practical technique for patients with vaginal agenesis. Further studies on long-term sexual function are needed in patients with vaginal agenesis; however, the described procedure demonstrates successful anatomic function of the neovagina regarding vaginal length and caliber to accommodate self-dilation and good patient satisfaction and cosmesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant T32HD007440 – Dr. Chan).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laufer MR. Congenital absence of the vagina: in search of the perfect solution. When, and by what technique, should a vagina be created? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:441–444. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG Committee Opinion Nonsurgical diagnosis and management of vaginal agenesis. Number 274, July 2002. Committee on Adolescent Health Care. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;79:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gargollo PC, Cannon GM, Jr., Diamond DA, Thomas P, Burke V, Laufer MR. Should progressive perineal dilation be considered first line therapy for vaginal agenesis? J Urol. 2009;182:1882–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vecchietti G. [Creation of an artificial vagina in Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome] Attual Ostet Ginecol. 1965;11:131–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G, Fontana E, Restelli E, Bruni V. The laparoscopic Vecchietti's modified technique in Rokitansky syndrome: anatomic, functional, and sexual long-term results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:377 e1–377 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen LM, Lucco KL, Brown CM, Spitzer RF, Kives S. Psychosexual and functional outcomes after creation of a neovagina with laparoscopic Davydov in patients with vaginal agenesis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2272–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin JF., XIV The formation of an artificial vagina by intestinal transplantation. Ann Surg. 1904;40:398–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klingele CJ, Gebhart JB, Croak AJ, DiMarco CS, Lesnick TG, Lee RA. McIndoe procedure for vaginal agenesis: long-term outcome and effect on quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1569–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00938-4. discussion 1572-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmonds DK. Congenital malformations of the genital tract and their management. Best practice & research. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;17:19–40. doi: 10.1053/ybeog.2003.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIndoe AH. The treatment of congenital absence and obliterative conditions of the vagina. Br J Plast Surg. 1950;2:254–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callens N, De Cuypere G, De Sutter P, et al. An update on surgical and non-surgical treatments for vaginal hypoplasia. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:775–801. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davydov SN. [Colpopoeisis from the peritoneum of the uterorectal space] Akush Ginekol (Mosk) 1969;45:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Mora J, Isnard R, Castellvi A, Lopez Ortiz P. Neovagina in vaginal agenesis: surgical methods and long-term results. J Ped Surg. 1992;27:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90093-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wee JT, Joseph VT. A new technique of vaginal reconstruction using neurovascular pudendal-thigh flaps: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:701–709. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198904000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karateke A, Haliloglu B, Parlak O, Cam C, Coksuer H. Intestinal vaginoplasty: seven years' experience of a tertiary center. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2312–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies MC, Creighton SM, Woodhouse CR. The pitfalls of vaginal construction. BJU Int. 2005;95:1293–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner-Warwick R, Kirby RS. The construction and reconstruction of the vagina with the colocecum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashworth MF, Morton KE, Dewhurst J, Lilford RJ, Bates RG. Vaginoplasty using amnion. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fotopoulou C, Sehouli J, Gehrmann N, Schoenborn I, Lichtenegger W. Functional and anatomic results of amnion vaginoplasty in young women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarwar I, Sultana R, Nisa RU, Qayyum I. Vaginoplasty by using amnion graft in patients of vaginal agenesis associated with Mayor-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson ND, Rosenblatt PL. Use of Interceed Absorbable Adhesion Barrier for vaginoplasty. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:1048–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davydov SN. [Modification of colpopoiesis from peritoneum of the rectoenterouterine recess] Akush Ginekol (Mosk) 1972;48:56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman D. The use of peritoneum in the construction of a vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;40:835–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panici PB, Bellati F, Boni T, Francescangeli F, Frati L, Marchese C. Vaginoplasty using autologous in vitro cultured vaginal tissue in a patient with Mayer-von-Rokitansky- Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2025–2028. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCraw JB, Massey FM, Shanklin KD, Horton CE. Vaginal reconstruction with gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:176–183. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton KE, Davies D, Dewhurst J. The use of the fasciocutaneous flap in vaginal reconstruction. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;93:970–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb08018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flack CE, Barraza MA, Stevens PS. Vaginoplasty: combination therapy using labia minora flaps and lucite dilators--preliminary report. J Urol. 1993;150:654–656. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35575-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chudacoff RM, Alexander J, Alvero R, Segars JH. Tissue expansion vaginoplasty for treatment of congenital vaginal agenesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:865–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yesim Ozgenel G, Ozcan M. Neovaginal construction with buccal mucosal grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2250–2254. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000060088.19246.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin WC, Chang CY, Shen YY, Tsai HD. Use of autologous buccal mucosa for vaginoplasty: a study of eight cases. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:604–607. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao M, Li P, Li S, Li Q. Use of autologous micromucosa graft for vaginoplasty in vaginal agenesis. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:645–649. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31819adfab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li FY, Xu YS, Zhou CD, Zhou Y, Li SK, Li Q. Long-term outcomes of vaginoplasty with autologous buccal micromucosa. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:951–956. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimsby GM, Bradshaw K, Baker LA. Autologous buccal mucosa graft augmentation for foreshortened vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:947–950. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimsby GM, Baker LA. The use of autologous buccal mucosa grafts in vaginal reconstruction. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15:428. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simman R, Jackson IT, Andrus L. Prefabricated buccal mucosa-lined flap in an animal model that could be used for vaginal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1044–1049. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200203000-00039. discussion 1050-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]