Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths among men in the United States. Patients with advanced prostate cancer are vulnerable to difficult treatment decisions because of the nature of their disease.

Objective

To describe and understand the lived experience of patients with advanced prostate cancer and their decision partners who utilized an interactive decision aid, DecisionKEYS, to make informed, shared treatment decisions.

Interventions/Methods

This qualitative study uses a phenomenological approach that included a sample of thirty-five pairs of patients and their decision partners (16 pairs reflected patients with less than 6 months since their diagnosis of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC); 19 pairs reflected patients with more than 6 months since their diagnosis of mCRPC). Qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews was conducted describing the lived experience of patients with advanced prostate cancer and their decision partners using an interactive decision aid.

Results

Three major themes emerged: 1) the decision aid facilitated understanding of treatment options, 2) quality of life was more important than quantity of life, and 3) contact with healthcare providers greatly influenced decisions.

Conclusions

Participants believed the decision aid helped them become more aware of their personal values, assisted in their treatment decision-making, and facilitated an interactive patient-healthcare provider relationship.

Implications for Practice

Decision aids assist patients, decision partners, and healthcare providers make satisfying treatment decisions that affect quality/quantity of life. These findings are important for understanding the experiences of patients who have to make difficult decisions.

Keywords: prostate cancer, decision-making, quality of life, decision aid, decision partners

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. In 2016, an estimated 180,890 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, and approximately 26,120 men will die of the disease1. In a lifetime, approximately 14% of all men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer2.

Patients with advanced prostate cancer, such as metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), may experience pain during urination, blood in his urine, and urinating frequently at night. Metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer is defined as cancer of the prostate that progresses despite the deprivation of androgen. Metastatic disease may not exhibit symptoms; however, bone pain, weight loss, or abnormal swelling in the feet may be experienced by the patient. Although there are treatment interventions targeting patients with advanced prostate cancer, survival rates have been relatively unchanged3–5.

There are numerous difficult decisions that patients with advanced prostate cancer must make, including treatment options, cost of care, and family involvement; however, over time patients with advanced cancer often regret some past decisions6–8. Many factors may increase the likelihood that patients will not have complete information at the time it is needed in order to optimize decision making, for example time constraints, forgetting to ask questions, and provider-patient miscommunication9–12. Treatment decisions in particular are important in relationship to patients’ health outcome13. Patients with advanced prostate cancer must often choose among hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or stopping treatments14. There are benefits and risks to each of these options. There are also risks related to these options, including hot flashes, pain, fatigue, diarrhea, and infections14. Treatment decisions may be difficult for a number of reasons. Patients may feel they are burdening caregivers if they take the treatment due to high treatment costs and other associated consequences of treatment15–17.

Many patients with advanced prostate cancer struggle with treatment decisions. Stressors can arise, such as coping with treatment side effects and balancing providers’ recommendations with those of family/friends’ desires. Men with advanced prostate cancer can be challenged by the side effects from the treatments used to decrease the progression of the disease. These side effects include fatigue, hot flashes, bone pain, osteoporosis, erectile dysfunction, and urinary incontinence. In addition, men who live with an incurable disease often struggle with psychosocial issues, such as depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and social isolation18,19. If patients and healthcare providers fail to engage in a systematic, informed, shared decision-making process (a collaborative process whereby patient and healthcare provider make a health care decision together, taking in account scientific/clinical evidence and the patient’s/decision partner’s values and preferences)20, there is a greater chance that the patient will be dissatisfied and regretful regarding the decisions that were made8,21,22. Moreover, decision partners may become “proxies” in interactions with healthcare providers; but, they often misunderstand the patient’s informational and decision needs23.

Decision aids can help patients apply specific health information while actively participating in health-related decision making24,25. To date, decision aids have primarily been applied to localized disease with an emphasis on treatment knowledge or options. Decision aids are most effective when they are tailored, interactive, collaborative, and focused on the priorities of the individual patient25–29; but, interactive decision aids are rarely implemented28. In this article, a collaborative, interactive decision aid for patients with advanced prostate cancer that focuses on patient priorities was evaluated to assess its use in facilitating informed, shared decisions about treatments that affect quality of life.

Background

There are a number of decision aids for patients with localized cancers; however, they often provide only disease content and are not truly interactive25. Very few decision aids focus on the advanced stages of cancer, particularly in prostate cancer. Existing decision aids are largely patient-focused, and may be inappropriate for use with patients with advanced cancers where patients may lose the ability to make decisions as the disease progresses.

Chosen decision aid for study

DecisionKEYS for Balancing Choices: Cancer Care, was developed to improve decision making for patients by enhancing the shared, informed decision-making process and reducing decisional conflict30. This decision aid is intended to: improve decision-making skills when there are multiple complex and stressful choices; help with a specific decision; and provide structured time for support by healthcare providers for decision making. The decision aid consists of 7 components (Table 1): 1) education pamphlets, 2) decision-making theory description, 3) a decision balance sheet that helps prioritize choices, 4) structured time with a healthcare provider, 5) treatment decision collaboration with the decision partner, 6) participation treatment decision preference level, and 7) audio CDs that discuss decisions what other patients with cancer have made and how they made them. The series of decision balance sheets includes pros and cons for oneself and others in a four-cell table. The decision aid’s audio component and the balance sheet are to organize and empower participants to effectively engage with healthcare providers. The decision aid is coupled with a valid and reliable computer-assisted quality of life instrument, Prostate Cancer Symptom Scale (PCSS), using an electronic handheld device to provide immediate patient reported outcome (PRO) results in an instant color graphic summary report over the treatment period. The 18-item self-reported PCSS has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7, which indicates an acceptable reliability. The healthcare provider participates in the interactive decision aid process through reviewing the priorities on the balance sheets with the patient and the decision partner.

Table 1.

Key components of a decision aid for adults with cancer

| DecisionKEYS for balancing choices: cancer care | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component | Content Elements | Process |

| Social support | Because patients generally do not make decisions in isolation, each patient is asked to choose a supporter (defined as any family member or concerned other who consistently provides emotional support) to accompany the patient to the clinic visits and participate in the decision process with the patient. | Ongoing inclusion of a support person throughout the process if available. |

| Anticipatory guidance related to the disease and treatment | Includes standard/usual care at the site (e.g., what to do about treatment side effects, signs of an infection, how quality of life is measured, why a treatment would be changed or stopped) using the clinics’ existing patient education pamphlets, such as those developed by the National Cancer Institute or Cancer Care National Office. | Content elements have been reviewed by a panel of experts for each type of cancer of interest. The brochures are helpful, but not the primary source of information, which rests with the physician. |

| A brief quality decision making process tutorial | Teaches parts of a psychological theory in the form of a “Decision Making Guide” (a synopsis of the Janis & Mann’s decisional conflict theory), to provide understanding of “why” quality decision making is important and how it affects satisfaction/regret of a consequential decision. The decision theory has been simplified into an easy-recall method by Hollen using a linear graphic diagram. | Handout with graphic depicting the theory is used at clinic visit and then provided to the patient/supporter pair to also review at home. |

| Patient’s decision participation preference | Determines the patient’s preference for level of participation in treatment decision-making, and shares this preference with the physician as a part of each decision within the intervention. | Control Preference Scale is used at each decision as preference may change over time. |

| Normalization | Provides the context of what others in similar situations have done, using the “Cancer Survival Toolbox: An Audio Resource Program” (latest edition) [© 2007; National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, Oncology Nursing Society, Association of Oncology Social Work, and Genentech BioOncology]. The program includes a basic skills set of six topics: (1) Communicating; (2) Finding Information; (3) Making Decisions; (4) Solving Problems; (5) Negotiating; and (6) Standing Up for Your Rights. To ensure a practical intervention, the overview is used. | CD Toolkit and CD player are in CD Home Kit for the patient/CPP dyad to keep for their own. Each dyad is shown how to use the CD player and a checklist is provided that outlines the three CDs for the program and amount of time needed to listen to each one. |

| Values clarification and preference discussion with several difficult decisions during treatment | Uses a decision balance sheet (a summary report for values/concerns/conflict designed by Janis and Mann) to weigh in terms of the benefits and risks for oneself and others, resulting in values clarification for the patient and care provider. The balance sheet exercise involves completion of a four-cell table related to the pros and cons for self and others, which was reviewed by two panels of experts (decision making and type of cancer). The final entry is the decision preference. | A balance sheet for the consequential decision is used in an interactive process at the clinic visit. |

| Structured time with oncology professionals to discuss difficult decisions | To enhance decision making to an informed, shared decision-making process, additional time is needed with the oncology professionals (at least 15–30 minutes of additional time with the oncology nurse at each decision time point, and 5 min of additional structured time with the oncologist). | Physician presents initial treatment choices to the patient (pair); nurse helps the patient (pair) process the information using the decision balance sheet; physician then uses information from the nurse to enhance the decision making process and answer further questions; physician then assures that the treatment decision is acceptable to the patient (pair). |

Ref: Hollen et al., 2013, Support Care Cancer, p. 893

Underpinning theory

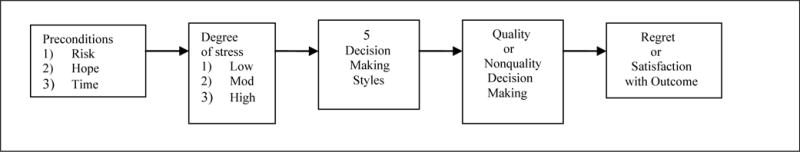

The Janis and Mann’s31,32 conflict theory of decision making, underpins the decision aid. As seen in Figure 1, this theory’s basis is that a certain degree of stress from preconditions (risk, hope, time) affects a person’s decision-making style, the quality of the decision, and ultimately the level of satisfaction or regret with the outcome. The theorists describe four descriptive styles of decision making, operationalized as non-quality styles: (a) unconflicted adherence (with low stress), (b) unconflicted change (with low stress), (c) defensive avoidance (with high stress), and (d) hypervigilance (with high stress). These four non-quality styles lead to the outcomes of more regret, less satisfaction, and a greater likelihood of changing one’s choice. The theory also prescribes a normative style, known as vigilance, which is operationalized as quality decision making, based on clarifying goals and values involved in the decision, canvassing options, searching and evaluating information, contrasting and weighing alternatives, and making contingency plans for implementation. Vigilance is often associated with moderate stress (enough to pay attention to important cues and seek out information, but not too much to be distracted and immobilized by anxiety). This style leads to less regret, more satisfaction, and less likelihood of reversing one’s choice. The decision aid places emphasis on the preconditions of risk, hope, and time by oncology professionals (guidance is given through a brief tutorial of the theory with a diagram), more time for clarifying options, values, and patient preferences (through use of a tailored decisional balance sheet), and more time for support (more structured time by the healthcare providers). This allows patients and their decision partners to recognize they did their best in following a quality decision-making process and will be less likely to feel regret about their decision.

Figure 1. Diagram of theory adapted for brief tutorial.

Ref: Hollen et al., 2013, Support Care Cancer, p. 891

Methods

Design

A phenomenological approach was used in this study to examine the experiences of patients with advanced prostate cancer and their decision partners. A hermeneutic phenomenological approach was used to interpret narrative in the context of exploring, describing, and interpreting participants’ experiences that are complex and not understood completely33. A semi-structured interview guide was developed by the authors and was used to capture the narrative of the participants’ experiences and perceptions of the intervention. This article reports the qualitative findings.

Setting and Sampling Plan

Participants were recruited at the University of Virginia Emily Couric Cancer Center in Charlottesville, Virginia and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Serial screenings of the clinics’ appointment rosters were conducted by the study nurse and the physician to determine which patients were eligible for the study. Once a patient was identified as eligible, the physician briefly described the study and introduced the study nurse to the patient/decision partner to discuss and answer questions about the study. For those patients who agreed to participate, written informed consent was obtained from each patient and decision partner prior to participation in the study. Participants included 35 pairs of patients and their decision partners (16 pairs reflected patients less than 6 months since their diagnosis of mCRPC; 19 pairs reflected patients more than 6 months since their diagnosis of mCRPC). Inclusion criteria for the participants were: 1) diagnosed with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; 2) disease progression despite testosterone castration levels; 3) Karnofsky Performance Status between 60–100%; 4) life expectancy greater than six months; 5) 18 years old or older; 6) having a decision partner (defined as a patient-selected person who provides support, care, or assistance in decision-making); and 7) the ability to understand English. The exclusion criterion was any documented diagnoses of severe psychiatric issues.

Data Collection Procedures

Institutional review board approval was obtained at both medical institutions. The study’s goals, procedures, and decision aid administration were discussed with the study nurses to ensure understanding of the protocol. Patients and decision partners completed the decision aid intervention within the clinic settings to help them make the treatment decision that was right for them. The intervention was then discussed with the participants during the time of the clinic visit that the physician presented the treatment options. Following the decision aid intervention and after the participants’ made their decision about treatment with the help of the physician and nurse interventionists, an audio-recorded telephone interview with both the patient and their decision partner was conducted lasting approximately one hour.

Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed and potential identifiers were removed from the interviews to maintain data confidentiality. Participants’ thick descriptions of their experiences with the intervention and decision-making process were captured34,35. Thick descriptions are defined as the way that data is described in a comprehensive manner that builds an analytical explanation of what has occurred. An iterative approach, defined as the authors ongoing analysis of the data to narrow the categories, allowed themes to emerge. The first two authors read the transcripts several times to be immersed in the data, coded the transcripts, identified strips (short data extracts that capture important aspects of participants’ experiences), and then created categories from which themes were formed. The authors independently reviewed transcripts to validate the themes then confirmed the results among themselves creating credibility, dependability, and confirmability36,37. Credibility was established by active engagement with the narratives and data as well as through member checking. Dependability and confirmability were established through the use of an audit trail. An exhaustive text description clarifying the lived experience of patients with advanced prostate cancer and their decision partners assisted the authors in understanding the phenomenon. This process allows for transferability of the findings36. Descriptive analysis was gathered to examine characteristics of the sample. Descriptive data were analyzed using SPSS®, version 22.

Findings

Forty-one pairs were categorized as having a man diagnosed with mCRPC. Thirty-five pairs (16 pairs with less than 6 months of mCRPC and 19 pairs with greater than 6 months of mCRPC; total of 70 participants) completed the recorded telephone interviews. Descriptive characteristics are presented for patients and their decision partner (Table 2).

Table 2.

Presenting Clinical Profiles of Patients and their Chosen Decision Partners Facing Difficult Decisions related to Prostate Cancer (N = 70 participants)

| Characteristics | Early Stage Advanced Prostate Cancer (n = 32 participants) |

Later Stage Advanced Prostate Cancer (n = 38 participants) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Patients (n = 16) |

Decision Partners (n = 16) |

Patients (n = 19) |

Decision Partners (n = 19) |

|

|

| ||||

| Age | 74 (median) | 64 (median) | 72 (median) | 60 (median) |

| Gender | 100% men | 13% men | 100% men | 89% women |

| Married | 87% | 100% | 79% | 79% |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 63% | 63% | 84% | 84% |

| African American | 31% | 31% | 16% | 16% |

| Latino | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (prefer not to answer) | 6% | 6% | 0 | 0 |

| School Years Completed | 16 (median) 6–20 (range) |

16 (median) 8–21 (range) |

16 (median) 0–22 (range) |

16 (median) 12–23 (range) |

| Income | ||||

| (<$40,000) | 25% | 25% | 47% | 37% |

The three themes (Table 3), that emerged described the lived experience of patients with advanced prostate cancer, mCRPC, and their decision partners at different points in the cancer trajectories (less than 6 months of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) greater than 6 months of mCRPC). These themes were: 1) the decision aid facilitated understanding of treatment options; 2) quality of life was more important than quantity of life; and 3) contact with the healthcare providers greatly influenced decisions.

Table 3.

Emerged Themes

| Themes |

|---|

| Decision aid facilitated understanding of treatment options |

| Quality of life was more important than quantity of life |

| Contact with the healthcare providers greatly influenced decisions |

Decision aid facilitated understanding of treatment options

Participants believed the decision aid was helpful in understanding treatment decisions. Patients and decision partners thought the decision aid was helpful in making their treatment decision. The decision aid is a tool that is intended to provide patients and their decision partners with assistance to examine options in a manner that made sense to them. One participant with less than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

It took us a little time to know what was the right thing to do… You look at your options and what it cost. And, what are you giving up with it? And, what is it going to do for you? So, yeah, your program helps decision making from that standpoint.

Many participants had prostate cancer for years (median, 8 years and 9 months) before their disease had progressed into advanced stage and reported they would have benefited from the decision aid earlier. One participant with less than 6 months of mCRPC said,

It would have really been great if my family doctor offered this to me when he said I should go to an urologist for a follow-up on my rising PSA.

A wife of a man with greater than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

I think they [balance sheets] were helpful. I recall my husband being a little surprised at some things that the balance sheet mentioned…things that he hadn’t really thought about when we began to discuss chemotherapy or its ramifications.

Participants viewed the decision aid as helpful in making treatment decisions. The decision aid highlighted issues that participants were unaware of thereby helping them consider and discuss issues in-depth. By patients and decision partners being able to discuss issues more thoroughly, and providing time to do so, it allowed them to have a better understanding and feel more confident in the decisions that they made.

Quality of life was more important than quantity of life

Participants agreed that quality of life was more important than extending life at the cost of suffering treatment complications. Patients felt that treatment side effects decreased the ability for participants to enjoy the remaining time they had alive. Participants did not want to have a longer life and have to be in pain or discomfort. A participant with less than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

And you know that’s what was always important to me from the beginning, is that anything we could do to improve the quality of life and not just extend it, would be good. But, if all we were doing is extending it [life], then I didn’t [want that], and as it turned out, it was as I feared. It [treatment side effects] robbed me of what little quality of life I had at the time, and so that’s when the decision was made to stop [treatment].

Often it was not only the patients who believe quality of life is more important, but it was their decision partner. A son of a man with less than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

Before, it would be really hard to do anything for him (father). But, I think when he used the decision-making process from the decision aid to come to the decision, it was his quality of life that mattered most.

Participants, particularly those with less than 6 months of mCRPC, viewed quantity of life as less important than quality of life. Advanced prostate cancer treatment complications can decrease patients’ urinary continence, physical energy, emotional stability, and mental concentration. These and other side effects can inhibit a man from completing daily tasks and enjoying life.

Contact with the healthcare providers greatly influenced decisions

Participants found that using the decision aid with the healthcare team was helpful in their decision making. The decision aid facilitated closer patient-healthcare provider relationships, allowing more patient-centered and productive conversations. Those participants with greater than 6 months of mCRPC interacted with the nurses more often than with the physician; however, those patients with less than 6 months of mCRPC interacted with the physician more often than with the nurse. When asked if the balance sheet (prioritizing treatment decision benefits and risks) helped the conversation between the patient/decision partner and the healthcare provider, a man with greater than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

I think the decision aid would be a good tool for folks to have on the front end. The process of the decision aid when you talk through pros and cons of difficult decisions with the oncology nurse…so they know what are your priorities… there can be a more meaningful discussion between you and the healthcare provider. It was a more efficient clinical visit.

The son of one participant with less than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

I thought he [the patient] was well informed. I had confidence that he thought clearly about the decisions he made, and he regularly questioned the doctors on why a certain treatment was being advised and my comfort level was okay. I thought he was very engaged in the decision making and was very proactive in having physicians explain the treatments they recommended. The decision aid helped with this.

Participants stated that the decision aid benefited interactions with their healthcare provider. Participants felt they had more meaningful conversations with the healthcare provider after discussing their values.

A gentlemen with less than 6 months of mCRPC stated,

Many times providers have frequent notions of what’s good for you. The patients generally… don’t disagree with the doctor. So if the doctor says, “Oh, I think we ought to do this and that and something else” most people will go with it… …whether they really think that’s what they should do or not. And, it’s at that point… that’s when the patient should ask questions. I think a lot of patients would not. The program [decision aid] would help give them the information early on… to ask those questions.

Facilitating more interactive contact with the healthcare provider as well as the oncology nurse, improved patients’ ability and willingness to ask questions and discuss treatment decisions. Providing the interactive decision aid immediately following the presentation of options by the physician was perceived as important in allowing time to process the information. Patients and their decision partners could absorb the information and ask questions through the balance sheet process with the oncology nurse. The oncology nurse provided a brief summary of participants’ remaining concerns to the physician, which helped the physician focus on those concerns. The follow-up conversation between the participants and healthcare provider to come to a treatment agreement was deemed valuable for patients and decision partners faced with complex difficult decisions.

Discussion

Some qualitative themes emerged differently from the sample based on the length of time the men were diagnosed with mCRPC. This suggests that patients with less than 6 months of mCRPC may have different needs and decisions to make than those with greater than 6 months of mCRPC due to disease progression, family/friend support, and life experience with the disease. Patients do not often make decisions in isolation, but they discuss difficult decisions with others (i.e. family, friends) to help them with their decision38,39.

The decision aid was perceived as positive and helpful to patients and their decision partners in making treatment decisions. The decision aid assisted patients with advanced prostate cancer, mCRPC, to understand the treatment options so that the patients can make informed, shared treatment decisions. The decision aid balance sheets encouraged participants to discuss issues that took priority. Participants believed they were supported by their healthcare provider and oncology nurse and that treatment decisions were influenced by their discussions. The decision aid allowed patients and decision partners more time to feel more comfortable in asking questions and being an active member in the decision-making process along with their healthcare provider. The underpinning conflict theory of decision making, contributed by emphasizing pictorially why decreasing stress and increasing understanding of treatment options would likely increase satisfaction of the patient’s treatment decision. This outcome is consistent with a systematic review of knowledge through use of decision aids in oncology studies40. Also reported in this systematic review40, there were no identified themes of increased anxiety in using decision aids.

The participants saw value in having close contact with their healthcare provider and oncology nurse. The physician and nurse interacted with each participant during the intervention; however, there was more discussion of the physician’s role by the less than 6 months of mCRPC group, and with the nurse’s role for the greater than 6 months of mCRPC group. The reason for this may be that the less than 6 months of mCRPC participants were more focused on their medical diagnosis/treatment and interacted with the physician more. They may be in the process of deciding whether or not to start cancer treatment. Also, they may have chosen the medical center based on a specific physician’s recommendation. Alternatively, greater than 6 months of mCRPC participants, who had lived longer with the disease and were considering changing or stopping cancer treatment, were more focused on other issues discussed with the nurse, such as the financial and emotional support of the family after the patient’s death. Similarly, the less than 6 months of mCRPC participants placed more emphasis on quality of life as more important than quantity of life than those individuals in the greater than 6 months of mCRPC group. Many in the less than 6 months of mCRPC group revealed they would rather forego continuing treatment that may extend life and focus more on quality of life. The reason may be related to patients with less than 6 months of mCRPC being more concerned with treatment-related symptoms (i.e., hormone induced hot flashes; chemotherapy pain, loss of energy, diarrhea, and loss of hair); whereas, those in the greater than 6 months of mCRPC group knew what to expect.

Participants in this study believed that this decision aid helped them make difficult treatment decisions. Patient-healthcare provider interactions were also enhanced due to the decision aid. The time to process the information with the oncology nurse provided focus on values and priorities, presented as risks and benefits for self and others in the decision balance sheet, was satisfying for many participants. These findings are similar to other studies in which patients’ were more satisfied with their decision when they are more engaged in the shared decision-making process41. Patients and decision partners were willing to use and saw value in the decision aid. In the larger framework of prostate cancer decision aids, which usually only provide disease education, this study’s interactive decision aid, which required patients’ active engagement and participation, was positively viewed by patients and their decision partners.

Study Limitations

One limitation to this study was the socioeconomic characteristics of this sample. The majority of the predominantly college-educated sample had an annual income that was above $40,000. Patients with a lower socioeconomic status may have different needs and concerns related to treatment decisions. The decision partner sample demographic was predominantly comprised of female spouses. The study’s experiences with the decision aid by the decision partners and the interaction with the patient may not be reflective of those decision partners who are male and/or the children of patients with advanced prostate cancer. The family role dynamics and reconciliation of treatment decision among this group might be different from other types of decision partners. Another limitation may be that the decision aid was tested with patients who were predominantly Caucasian. Other races may have different needs, values, and experiences when making treatment decisions. A larger study involving a more diverse population is needed to determine the use of the decision aid among different races. All of the participants in this study were willing to utilize a decision aid during their decision making process; but, there might be important differences in decision making for those patients who are not interested in using decision aids. That information may provide clues to other services or instruments that would be valuable for those patients with advanced prostate cancer who may not want assistance from a decision aid. In addition, the interviews were with the patient and their decision partner together, which may have placed some constraints on speaking freely; even though both patients and decision partners were asked when scheduling the interviews if they preferred to be interviewed separately or together. Each participant stated a preference to be interviewed during the same time.

Implications for Research and Practice

Many patients with advanced prostate cancer, mCRPC, and their decision partners struggle with treatment decision-making. Poor prognosis is compounded by the fact that decision making is complex, and conflicts arise, particularly surrounding quality of life issues42–44. The findings support the need for increased use of interactive decision aids, which were found to be beneficial to patients with advanced prostate cancer in making difficult treatment decisions. The decision aid helped the participants in ways they perceived as important, such as becoming more aware of their own underlying values, facilitating time and support to convey this information to their providers, and providing additional opportunities to discuss the benefits and risks of different treatment options with healthcare providers and oncology nurses.

It is important to understand that patients may need more assistance than only providing additional treatment information in making difficult treatment decisions. A combination of treatment content, thoughtful interactions between patient and decision partners, and an understanding of the patient’s health priorities and what they consider a quality decision are important as healthcare providers engage with these patients. Healthcare providers should be aware of the patients’ needs and desires to live a life that is considered to be satisfactory to them, considering a disease that is advanced and incurable. More evidence is needed with larger samples to support use of this decision aid, DecisionKEYS, for patients with prostate cancer, as a prelude to common use in practice30,45.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to the patients who have participated in our program of research for sharing their thoughts, time, and reflections. We also thank the study nurses who were directly involved with the studies, in particular Debra Bliesner, MSN, RN, OCN and Patricia Featherston, RN.

Disclosure of Funding: National Cancer Institute (1R21CA131754-01) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Dr. Randy A. Jones, University of Virginia School of Nursing.

Dr. Patricia J. Hollen, University of Virginia School of Nursing.

Dr. Jennifer Wenzel, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

Dr. Geoff Weiss, University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Dr. Daniel Song, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Terran Sims, University of Virginia School of Nursing.

Dr. Gina Petroni, University of Virginia Public Health Sciences.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program database: 1973–2012. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. Updated 2016. Accessed March 7, 2016.

- 3.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tangen CM, Hussain MHA, Higano CS, et al. Improved overall survival trends of men with newly diagnosed M1 prostate cancer: A SWOG phase III trial experience (S8494, S8894 and S9346) J Urol. 2012;188(4):1164–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman-Censits J, Kelly WK. Enzalutamide: A novel antiandrogen for patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(6):1335–1339. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christie DR, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V. Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? A systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1002–1011. doi: 10.1002/pon.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brom L, De Snoo-Trimp J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Widdershoven G, Stiggelbout A, Pasman H. Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: A qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. 2015:1–16. doi: 10.1111/hex.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahal BA, Chen MH, Bennett CL, et al. The association between race and treatment regret among men with recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015;18(1):38–42. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu W, Deen D, Rothstein D, Santana L, Gold MR. Activating community health center patients in developing question-formulation skills: A qualitative study. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):637–645. doi: 10.1177/1090198110393337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillen MA, de Haes, Hanneke CJM, Smets EMA. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician-a review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(3):227–241. doi: 10.1002/pon.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woods SS, Schwartz E, Tuepker A, et al. Patient experiences with full electronic access to health records and clinical notes through the my HealtheVet personal health record pilot: Qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e65. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robben S, van Kempen J, Heinen M, et al. Preferences for receiving information among frail older adults and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2012;29(6):742–747. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shore ND, Karsh L, Gomella LG, Keane TE, Concepcion RS, Crawford ED. Avoiding obsolescence in advanced prostate cancer management: A guide for urologists. BJU Int. 2015;115(2):188–197. doi: 10.1111/bju.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayasekera J, Onukwugha E, Bikov K, Mullins CD, Seal B, Hussain A. The economic burden of skeletal-related events among elderly men with metastatic prostate cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(2):173–191. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sammon JD, McKay RR, Kim SP, et al. Burden of hospital admissions and utilization of hospice care in metastatic prostate cancer patients. Urology. 2015;85(2):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stokes ME, Ishak J, Proskorovsky I, Black LK, Huang Y. Lifetime economic burden of prostate cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:349. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers SK, Pinnock C, Lepore SJ, Hughes S, O’Connell DL. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for men with prostate cancer and their partners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):e75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Sousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: A clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(2):120–127. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafir A, Rosenthal J. Shared decision making: Advancing patient-centered care through state and federal implementation. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(17):1616–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poon P. The information needs, perceptions of communication and decision-making process of cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Journal of Pain Management. 2012;5(1):93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo L, Slater S. Challenges in providing culturally-competent care to patients with metastatic brain tumours and their families. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;36(2):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor A, Bennett C, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009;(3):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sepucha KR, Borkhoff CM, Lally J, et al. Establishing the effectiveness of patient decision aids: Key constructs and measurement instruments. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozanne EM, Howe R, Omer Z, Esserman LJ. Development of a personalized decision aid for breast cancer risk reduction and management. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2014;14:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jimbo M, Rana GK, Hawley S, et al. What is lacking in current decision aids on cancer screening? CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):193–214. doi: 10.3322/caac.21180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fowler FJ, Jr, Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):699–706. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Jones RA, et al. A theory-based decision aid for patients with cancer: Results of feasibility and acceptability testing of DecisionKEYS for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):889–899. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1603-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janis I, Mann L. Decision-making: A psychological analysis of conflict choice and commitment. New York, New York: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janis L, Mann L. Theoretical framework for decision counseling. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R. Hermeneutic phenomenology: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. CA: Thousand Oaks; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212–1222. doi: 10.1177/1049732315588501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shenton A. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information. 2004;22(63):75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: A framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLennon SM, Uhrich M, Lasiter S, Chamness AR, Helft PR. Oncology nurses’ narratives about ethical dilemmas and prognosis-related communication in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(2):114–121. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31825f4dc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):761–772. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kane HL, Halpern MT, Squiers LB, Treiman KA, McCormack LA. Implementing and evaluating shared decision making in oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(6):377–388. doi: 10.3322/caac.21245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gralla R, Hollen P, Davis B, Peterson J, Saad F. Determining issues of importance for patients with prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(18S):5138. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reyna V, Nelson W, Han P, Pignone M. Decision making and cancer. American Psychologist. 2015;70(2):105–118. doi: 10.1037/a0036834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz SJ, Belkora J, Elwyn G. Shared decision making for treatment of cancer: Challenges and opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):206–208. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones R, Steeves R, Ropka M, Hollen P. Capturing treatment decision making among patient with solid tumors and their caregivers. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40(1):E1–E8. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.E24-E31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]