CALHM1 is an essential ion channel component of the ATP neurotransmitter release mechanism in type II taste bud cells. Its contribution to type II cell resting membrane properties and excitability is unknown. Nonselective voltage-gated currents, previously associated with ATP release, were absent in cells lacking CALHM1. Calhm1 deletion was without effects on resting membrane properties or voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels but contributed modestly to the kinetics of action potentials.

Keywords: ATP release channel, voltage-gated ion channel, taste bud, voltage clamp

Abstract

Taste bud type II cells fire action potentials in response to tastants, triggering nonvesicular ATP release to gustatory neurons via voltage-gated CALHM1-associated ion channels. Whereas CALHM1 regulates mouse cortical neuron excitability, its roles in regulating type II cell excitability are unknown. In this study, we compared membrane conductances and action potentials in single identified TRPM5-GFP-expressing circumvallate papillae type II cells acutely isolated from wild-type (WT) and Calhm1 knockout (KO) mice. The activation kinetics of large voltage-gated outward currents were accelerated in cells from Calhm1 KO mice, and their associated nonselective tail currents, previously shown to be highly correlated with ATP release, were completely absent in Calhm1 KO cells, suggesting that CALHM1 contributes to all of these currents. Calhm1 deletion did not significantly alter resting membrane potential or input resistance, the amplitudes and kinetics of Na+ currents either estimated from action potentials or recorded from steady-state voltage pulses, or action potential threshold, overshoot peak, afterhyperpolarization, and firing frequency. However, Calhm1 deletion reduced the half-widths of action potentials and accelerated the deactivation kinetics of transient outward currents, suggesting that the CALHM1-associated conductance becomes activated during the repolarization phase of action potentials.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY CALHM1 is an essential ion channel component of the ATP neurotransmitter release mechanism in type II taste bud cells. Its contribution to type II cell resting membrane properties and excitability is unknown. Nonselective voltage-gated currents, previously associated with ATP release, were absent in cells lacking CALHM1. Calhm1 deletion was without effects on resting membrane properties or voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels but contributed modestly to the kinetics of action potentials.

taste cells located in taste buds in the oral cavity relay information to the brain about the types of molecules present in saliva. Salt and sour are detected by ion channel-based mechanisms in the apical membrane of type III cells. In contrast, sweet, bitter, and umami molecules are recognized by apical membrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) present in type II cells. In response to stimulation, types II and III cells fire action potentials that are essential for neurotransmitter release to afferent gustatory neurons (Avenet and Lindemann 1991; Béhé et al. 1990; Chen et al. 1996; Furue and Yoshii 1997; Huang and Roper 2010; Kimura et al. 2014; Murata et al. 2010; Roper 1983; Vandenbeuch and Kinnamon 2009; Yoshida et al. 2006). In type III cells, ion channel-mediated depolarization triggers tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ action potentials that activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels that supply Ca2+ for vesicular neurotransmitter release at synapses with gustatory neurons. In type II cells, TTX-sensitive Na+ action potentials are also generated, but they result from a stereotypic signal transduction cascade engaged by GPCR activation. Type II cells also possess a distinct mechanism of neurotransmitter release. Type II cells lack synapses and molecular machinery for regulated exocytosis, including absence of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Instead, the neurotransmitter, primarily ATP, is released by a voltage-gated nonvesicular ion channel mechanism (Huang et al. 2007; Kinnamon and Finger 2013; Ma et al. 2016; Medler 2015; Murata et al. 2010; Romanov et al. 2007, 2008; Taruno et al. 2013a). Whereas pannexins and connexin hemi-channels had been previously considered as candidates for the ATP release channels, it was recently shown that pannexins are not involved (Tordoff et al. 2015; Vandenbeuch et al. 2015) but that CALHM1 is an essential component of the ATP neurotransmitter voltage-gated release channel (Taruno et al. 2013b).

CALHM1 was initially discovered in a search for genes expressed in the brain that were associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Dreses-Werringloer et al. 2008). It was subsequently established that CALHM1 is a pore-forming subunit of a voltage-gated nonselective ion channel (Ma et al. 2012) with structural features that it shares through convergent evolution with connexin and pannexin families of channels, including a hexameric assembly of subunits surrounding a wide (~14A diameter) pore (Siebert et al. 2013). Genetic deletion of Calhm1 eliminated taste perception of sweet, bitter and umami substances by abolishing action potential-dependent ATP release in type II cells (Taruno et al. 2013b). It also strongly reduced the magnitude of a voltage-dependent, slowly activating nonselective current that had been previously associated with the ATP release mechanism (Romanov and Kolesnikov 2006; Romanov et al. 2007; Taruno et al. 2013b).

In addition to its role in peripheral taste perception as an ATP release channel, CALHM1 was shown to play a role in mouse cortical neuron excitability, since its genetic deletion altered the basal electrical properties of mouse cortical neurons, rendering them less excitable at low input stimulus strength, but transforming them from phasic to tonic responders with stronger depolarizing inputs (Ma et al. 2012). With its subsequent discovery as a fundamental component of the transduction machinery in type II taste cells (Taruno et al. 2013b), these results raise the possibility that CALHM1 may also influence the electrical properties of type II taste cells. To explore this possibility, here we have examined the resting and active membrane properties of type II cells acutely isolated from wild-type and Calhm1-knockout (KO) mice to determine the contribution of CALHM1 to these properties and whether CALHM1-associated channels are activated during action potentials in taste type II cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Generation of Calhm1−/− mice was previously described (Dreses-Werringloer et al. 2008; Taruno et al. 2013b). TRPM5-GFP/Calhm1−/− mice were generated by crossing transgenic TRPM5-GFP mice, generously provided by Dr. R. F. Margolskee (Clapp et al. 2006), with Calhm1+/− mice (129S × C57BL/6J mixed background). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free, temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Diet consisted of standard laboratory chow and double-distilled water. All methods of mouse handling were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health “Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.” Only transgenic mice expressing GFP were used in experiments. All experiments were performed with WT and Calhm1 knockout (KO) littermates of both sexes that were at least 3 mo old. Mouse genotypes were determined by real-time PCR (Transnetyx, Cordova, TN).

Taste bud cell isolation.

Animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation. The circumvallate taste epithelium was enzymatically delaminated, taste buds were collected from peeled epithelium, and dissociated single taste cells were collected as detailed previously (Taruno et al. 2013b). Briefly, 0.5 ml of a mixture of enzymes containing Dispase II (2 mg/ml; Roche), collagenase A (1 mg/ml; Roche), trypsin inhibitor (1 mg/ml; Sigma), elastase (0.2 mg/ml; Sigma), and DNase I (10 µg/ml; Roche) diluted in a Ca2+-Tyrode solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 5 Na-pyruvate, and 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) was injected under the lingual epithelium. After 30 min of incubation in Ca2+-Tyrode solution at room temperature, the epithelium was peeled off and incubated for 15 min in Ca2+-free Tyrode solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 glucose, 5 Na-pyruvate, and 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Gentle suction with a glass capillary pipette removed circumvallate cells from the taste buds. The isolated cells were placed on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and allowed to settle for ~60 min before electrophysiological recording.

Electrophysiology and data analysis.

All experiments were performed on isolated single green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing type II taste bud cells dissociated from circumvallate papillae from Calhm1−/− and WT littermates using standard patch-clamp procedures in the whole cell mode as described previously (Ma et al. 2012). All recordings were performed at room temperature (20~22°C). Data were acquired with an Axopatch 200B amplifier at 5 kHz. Currents were filtered by an eight-pole Bessel filter at 1 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz with an 18-bit analog-to-digital converter. Electrode capacitance was compensated electronically, and 60% of series resistance was compensated with a lag of 10 μs. Electrodes were made from thick-walled PG10150-4 glass (World Precision Instruments) and had a resistance of 4–7 MΩ in the recording conditions. HEKA Pulse software (HEKA Eletronik, Lambrecht, Germany) was used for data acquisition and stimulation protocols. Igor Pro was used for graphing and data analysis (WaveMetrics). Leak subtractions were not applied in the current study. Results are means ± SE. Student’s t-test was employed for statistical analyses.

Recording solutions.

In the whole cell current-clamp mode to record action potentials, and in the whole cell voltage-clamp mode to record Na+ and K+ conductances, the pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 K+, 6 Na+, 1 Mg2+, 1 Ca2+, 30 Cl−, 11 EGTA, 3 ATP3−, 0.3 GTP Tris salt, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 adjusted by methanesulfonic acid, ∼290 mosM. The bath solution contained (in mM) 150 Na+, 5.4 K+, 1.5 Ca2+, 1 Mg2+, 150 Cl−, 20 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 adjusted by methanesulfonic acid, ∼330 mosM.

RESULTS

Steady-state voltage-gated currents in acutely isolated WT and Calhm1-KO type II cells.

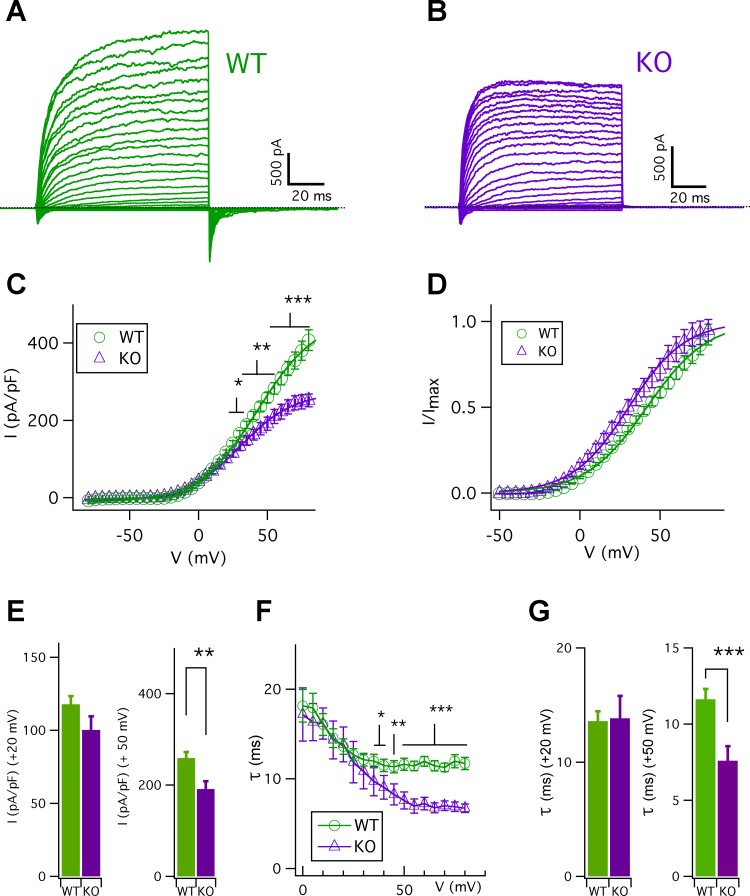

We examined the biophysical properties of type II taste cell membrane conductances using acutely isolated cells in a defined medium and stimulated them electrically. To determine whether CALHM1-associated channels are activated during action potentials, we first investigated if CALHM1 contributes to steady-state currents induced by 100-ms voltage pulses at a holding potential of −70 mV with physiologically relevant pipette and bath solutions (see materials and methods). Representative families of whole cell currents are shown for a WT cell (capacitance = 4.9 pF; Fig. 1A) and a Calhm1 KO cell (capacitance = 5.3 pF; Fig. 1B). The current-voltage (I-V) relations for the outward currents from WT and Calhm1-KO cells are shown in Fig. 1C, and their normalized I-V relations are shown in Fig. 1D. The I-V relations were fitted by a Boltzmann function with a half-activation voltage (V0.5) of ~39.4 mV and voltage dependence (Z0) of ~1.4 e for WT cells, and ~29.5 mV and ~1.5 e for Calhm1-KO cells, respectively. Thus CALHM1 contributes to the steady-state currents evoked by 100-ms voltage pulses by right shifting the I-V relation by 10 mV and increasing cell conductance at voltages >20 mV (Fig. 1, C and D). The average steady-state currents at 20 mV were not different between WT cells and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 1E, left; P = 0.10). In contrast, the currents in Calhm1 KO cells at 50 mV were significantly reduced (P < 0.005) compared with those in the WT cells (Fig. 1E, right). The activation time constants, obtained by single exponential fits of the outward activation currents, are shown in Fig. 1F. The time constants at 20 mV were ~15 ms, with no significant difference between WT cells and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 1G, left; P = 0.87). However, the activation time constant at voltages >35 mV was significantly increased in the WT type II cells (Fig. 1F). For example, the time constant at 50 mV in WT cells was significantly larger (P < 0.0005) than that in Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 1G, right). These results suggest that CALHM1-associated channels became activated during the 100-ms voltage pulses and provide an additional component to the outward currents at voltages >20 mV in WT type II cells. Notably, inward tail currents at −80 mV evoked by prepulses of 100-ms depolarizing voltages observed in WT type II cells were completely absent in Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 1, A and B). This indicates that CALHM1-associated channels contribute nearly completely to these inward tail currents. These observations are consistent with the notion that CALHM1 contributes to the steady-state outward currents at depolarized voltages.

Fig. 1.

Steady-state voltage-gated currents in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells. A and B: representative families of whole cell currents from WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells, respectively, evoked by 100-ms voltage pulses from −80 to 80 mV in 5-mV increments from a holding potential of −70 mV (see materials and methods for details of bath and pipette solutions). C: I-V relations for WT and Calhm1 KO outward currents, obtained by measurement of currents at end of pulses, normalized to individual whole cell capacitance. Solid lines are Boltzmann function fits with V0.5 and Z0 of 39.4 ± 2.4 mV and 1.4 ± 0.1 e for WT cells (n = 11) and 29.5 ± 1.3 mV and 1.5 ± 0.1 e for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (***P < 0.0005 for V0.5; P = 0.32 for Z0). D: I-V relations of outward currents for WT and Calhm1 KO cells, normalized to maximum currents (Imax) obtained by fitting of a Boltzmann function to individual cell currents. E, left: at 20 mV, steady-state outward currents were 117.8 ± 5.7 pA/pF for WT cells (n = 11) and 100.3 ± 9.32 pA/pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.10). Right, at 50 mV, steady-state outward currents were 258.8 ± 13.3 pA/pF for WT cells (n = 11) and 191.4 ± 16.9 pA/pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (**P < 0.005). F: voltage dependence of outward current activation time constants (τ) for WT (n = 11) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13), obtained by single exponential fits. Time constants were different between WT and Calhm1 KO cells at voltages >35 mV (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005). G, left: outward current activation time constants at 20 mV were 13.6 ± 0.9 ms for WT cells (n = 11) and 13.8 ± 1.9 ms for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.75). Right, outward current activation time constants at 50 mV were 11.6 ± 0.7 ms for WT cells (n = 11) and 7.6 ± 0.8 ms for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (***P < 0.0005). Whole cell capacitances were 4.6 ± 0.2 pF for WT cells (n = 11) and 4.8 ± 0.4 pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.45).

Membrane properties of type II taste cells.

Next, we asked whether deletion of Calhm1 affects membrane properties of type II taste bud cells. A range of resting membrane potentials from −40 to −65 mV has been reported for isolated type II cells from various species, including frog (Bigiani et al. 1998; Furue and Yoshii 1997; Suwabe and Kitada 2004), mud puppy (McPheeters et al. 1994; Roper 1983), rat (Chen et al. 1996), and mouse (Medler et al. 2003). Knowledge of the resting potentials in mouse type II cell is important for understanding how action potentials are generated in these cells, providing insights into whether voltage-gated Na+ channels are at resting states before stimulation. We used acutely isolated healthy cells from mice expressing GFP under the transient receptor potential channel M5 (TRPM5) promotor to unambiguously identify type II cells. The resting membrane potential was measured using a ramp protocol in current-clamp mode (Ma et al. 2012) and solutions similar to those used in taste bud cell studies (Chen et al. 1996; Furue and Yoshii 1997; Kimura et al. 2014). Resting membrane potentials were −65.1 ± 0.7 and −65.6 ± 0.8 mV for WT (n = 16) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 19), respectively (P = 0.49). The currents required to hold cells at approximately −70 mV (Ihold) were −15.2 ± 2.6 and −15.2 ± 2.3 pA for WT (n = 16) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 19), respectively (P = 0.98; holding potential in WT cells: −72.9 ± 1.6 mV, n = 16; in Calhm1 KO cells: −73.3 ± 1.2 mV, n = 19; P = 0.75). Whole cell membrane capacitance was not altered by deletion of Calhm1: 5.0 ± 0.2 and 5.2 ± 0.4 pF for WT (n = 16) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 19) cells, respectively (P = 0.65). These results indicate that the resting membrane potential is more hyperpolarized than reported in many studies and that CALHM1 does not affect the resting potential in type II cells.

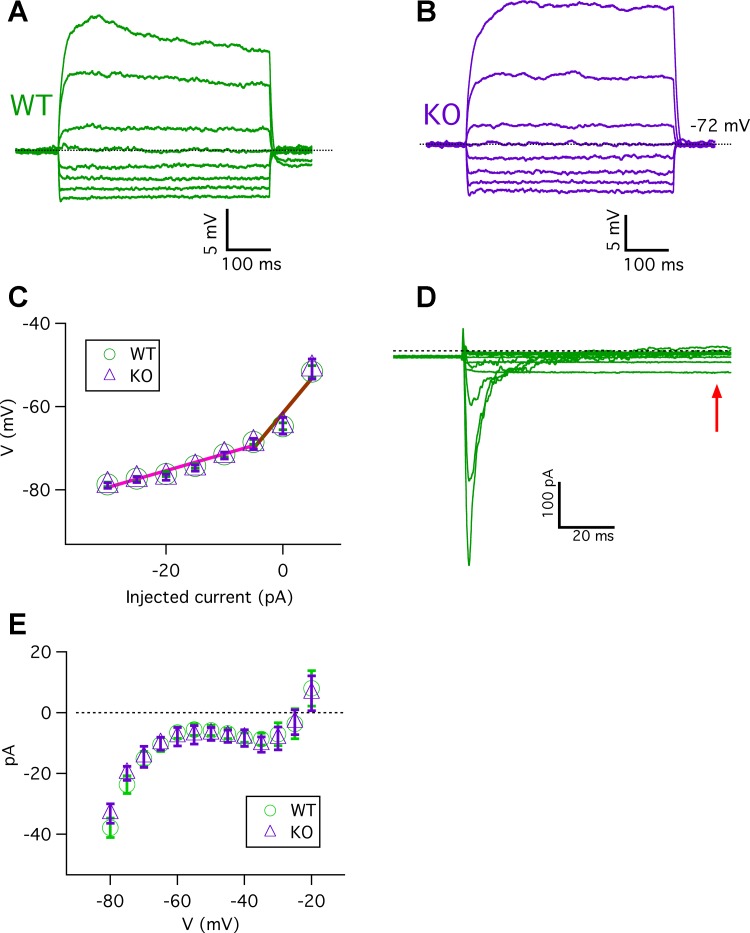

Membrane potentials were also recorded in current-clamp mode, with representative voltage traces from WT and Calhm1 KO cells shown in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively. The voltage-current (V-I) relations were determined at the end of 500-ms current pulses before firing action potentials (Fig. 2C). The membrane input resistances, determined as the slopes of linear fits to the V-I data, were ~400 MΩ for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells for hyperpolarizing current injections relative to the holding current. However, the membrane input resistances were ~1.5 GΩ for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells for depolarizing current injections relative to the holding currents, but before firing action potentials. These results suggest that CALHM1 does not contribute to the resting membrane properties of type II taste cells, in contrast to its contributions in mouse cortical neuronal cells (Ma et al. 2012). Of note, type II cells have lower input resistance within the −80- to −70-mV voltage range than between −70 and −50 mV, indicating that they have a background conductance in a voltage range in which voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels as well as CALHM1-associated channels are expected to be in closed states. To confirm this, membrane conductances over this range of voltages were evaluated by measuring currents evoked by 100-ms voltage pulses from −80 to −20 mV at a holding potential of −70 mV. A representative family of currents is shown in Fig. 2D from one WT type II cell, and the average steady-state I-V relations for WT and Calhm1 KO cells, determined at the end of the pulses, are shown in Fig. 2E. I-V relations showed a larger conductance between −80 and −70 mV than that at more depolarization potentials of −70 to −50 mV.

Fig. 2.

Membrane input resistances and voltage-gated background currents in type II cells. A and B: representative current-clamp recordings from WT (A) and Calhm1 KO cells (B) (Ihold = −10 pA) in response to 500-ms current pulses in 5-pA increments from −30 to + 5 pA every 10 s. Dotted lines indicate the holding potential level. C: membrane potential vs. injected currents for WT (n = 11) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) obtained from steady-state voltages at end of 500-ms current pulses without firing action potentials. Membrane input resistances within −80 to −70 mV were 413 ± 39 MΩ for WT (n = 11) and 432 ± 27 MΩ for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.85). Membrane input resistances within −70 to −50 mV were 1.51 ± 0.21 GΩ for WT (n = 11) and 1.58 ± 0.26 GΩ for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.59). Solid lines are linear fits to WT data. D: representative family of currents recorded in a WT type II cell. Currents were evoked by 100-ms voltage pulses from −80 to −20 mV in 5-mV increments from a holding potential of −70 mV. Dotted line indicates zero-current level. E: I-V relations over voltage range from −80 to −20 mV for WT (n = 5) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 4), with currents measured at end of 100-ms voltage pulses (indicated by arrow in D). Currents are not normalized to whole cell capacitance, which was 5.2 ± 0.5 pF for WT (n = 5) and 5.4 ± 0.5 pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 4). Cells with whole cell seal resistance >3 GΩ were chosen for this analysis.

Steady-state Na+ currents in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells.

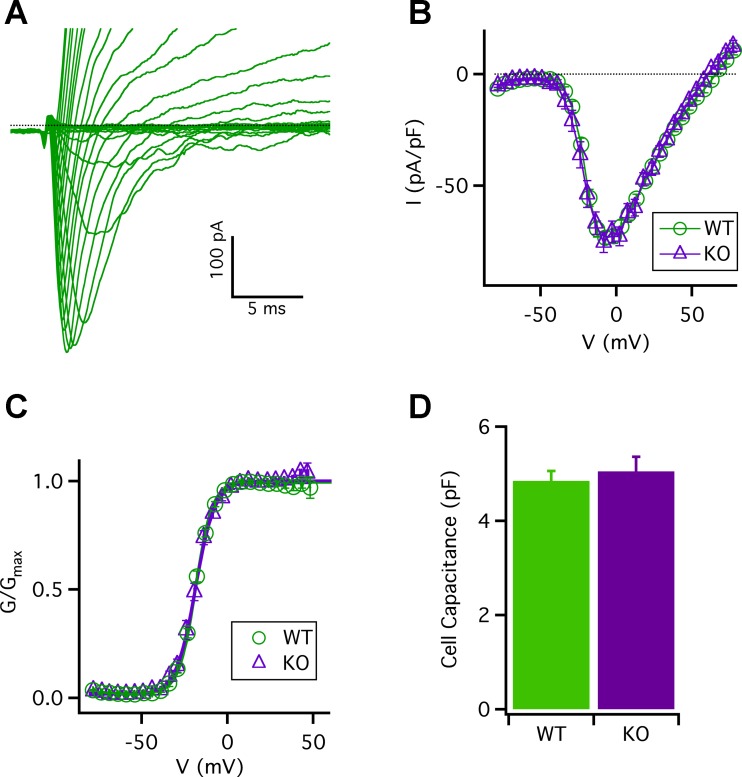

To further explore if CALHM1 influences type II cell excitability, we asked if deletion of Calhm1 affects voltage-gated Na+ currents. Whole cell voltage-gated Na+ and K+ currents were recorded from the same single cells analyzed in Fig. 1. A representative family of Na+ currents from a WT cell is shown in Fig. 3A. The I-V relations for inward Na+ peak currents from WT and Calhm1 KO cells are shown in Fig. 3B. The peak inward Na+ currents were approximately −75 pA/pF for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells, respectively (P = 0.15). The half-maximal activation voltage (V0.5) was approximately −20 mV for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells with a strong and similar voltage dependence (Z0 of ~6 e; Fig. 3C). The whole cell capacitances for cells used in these Na+ current measurements were similar for WT and Calhm1 KO cells (P = 0.52; Fig. 3D). These results suggest that deletion of Calhm1 does not alter the steady-state voltage-gated Na+ currents in type II cells.

Fig. 3.

Steady-state Na+ currents in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells. A: representative family of whole cell Na+ currents from WT type II cell (capacitance: 4.5 pF) evoked by 100-ms voltage pulses from −80 to +65 mV in 5-mV increments from a holding potential of −70 mV. Bath and pipette solutions are described in materials and methods. B: I-V relations of Na+ currents for WT and Calhm1 KO cells, obtained by measurements of peak inward currents, normalized to individual whole cell capacitance. Maximum peak inward currents near −10 mV were −73.5 ± 2.9 pA/pF for WT (n = 26) and −75.5 ± 4.6 pA/pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 18) (P = 0.15). C: Na+ conductance-voltage relations (G-V), fitted with a Boltzmann function with half-activation voltage (V0.5) and voltage dependence (Z0) of −18.8 ± 1.0 mV and 6.1 ± 0.4 e for WT (n = 26) and −19.6 ± 1.6 mV and 6.1 ± 0.5 e for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 18), respectively (P = 0.48 for V0.5; P = 0.94 for Z0). D: whole cell capacitance for cells used in Na+ current measurements was 4.9 ± 0.2 pF for WT (n = 26) and 5.1 ± 0.3 pF for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 18) (P = 0.52).

Action potential properties of type II cells.

CALHM1 does not appear to influence the resting membrane properties or voltage-gated Na+ channels in type II taste cells. However, in our previous studies in mouse cortical neurons, genetic knockout of Calhm1 altered membrane electrical properties, reducing excitability at low input stimulus strengths (Ma et al. 2012). Accordingly, in the current study we investigated whether knockout of Calhm1 alters the action potential properties of type II cells. Action potentials were generated by 500-ms current pulses in whole cell current-clamp mode in single GFP-positive type II cells from WT and Calhm1 KO mice. The properties of a single action potential were analyzed for the first action potential for each acutely isolated cell. A representative action potential is shown in Fig. 4A from a WT cell. Action potential thresholds, detected by measuring the change in dV/dt (Fig. 4B), were not different in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells (WT: −35.3 ± 0.5 mV, n = 16; KO: −34.6 ± 0.7 mV, n = 19; P = 0.18). The action potential overshooting peaks detected by Gaussian fits were 50.2 ± 2.8 mV (n = 16) and 50.5 ± 2.8 mV (n = 19) in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells, respectively (P = 0.94). The action potential half-width, detected by Gaussian fits from threshold to overshooting peak, was significantly shorter in cells from Calhm1 KO (2.1 ± 0.1 ms, n = 19) vs. WT mice (2.4 ± 0.2 ms, n = 16). In contrast, the afterhyperpolarization (AHP) was similar for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (WT: −56.6 ± 1.7 mV, n = 16; Calhm1 KO: −56.8 ± 1.5 mV, n = 19; P = 0.91). Thus, whereas CALHM1 does not appear to influence the threshold, AHP, and overshooting peak of single action potentials in type II cells, its deletion reduced the action potential half-width. These results suggest that CALHM1-associated channels become activated during the action potentials in type II taste cells.

Fig. 4.

Action potential properties in type II taste cells from WT and Calhm1 KO mice. A: representative single action potential (green trace) in a WT cell. Red solid line is Gaussian fit between two threshold voltages, which was used to determine the overshooting value and half-width for each action potential. B: first time derivative of the voltage (dV/dt) during the action potential in A. Threshold was defined as the voltage (red arrow) reached once dV/dt significantly increased from baseline.

Properties of trains of action potentials in type II cells.

Action potentials are required to activate voltage-gated ATP release channels in type II taste bud cells (Kinnamon and Finger 2013; Murata et al. 2010; Romanov et al. 2008; Taruno et al. 2013b). Understanding the properties of a train of action potentials may provide further insights into how action potentials activate the voltage-gated channels to release ATP. Injection of stronger 500-ms depolarizing current pulses resulted in repetitive action potential generation in both WT (Fig. 5A) and Calhm1 KO (Fig. 5B) type II cells. Increasing the amplitude of the injected currents increased the number of overshooting action potentials to a peak (~3 action potentials per 500 ms) in both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 5C). With >20-pA current injection, the number of overshooting action potentials declined, presumably due to Na+ channel inactivation (Fig. 5, A–C). In cells that generated a maximum number of action potentials, the average interval between the first and second action potential in a train of action potentials (Fig. 5D) was ~100 ms for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 5E). The action potential frequency, the reciprocal of the interval time, was ~10 Hz for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 5F). The interval between first and second action potentials was reduced by stronger depolarizing current injections. A 25-pA current injection enhanced action potential frequency to ~15 Hz for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (data not shown). These results indicate that type II taste cells fire repetitive action potential trains and that deletion of CALHM1 does not affect the action potential firing frequency induced by electrical stimulation in type II cells.

Fig. 5.

Trains of action potentials in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells. A and B: representative current-clamp recordings (Ihold = −10 pA) from WT and Calhm1 KO cells, respectively, in response to indicated depolarizing current injections. Dotted lines indicate 0 mV. C: number of overshooting action potentials during 500-ms depolarizing current injections in WT (n = 11) and Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13). D: expanded scale for the third KO action potential trace in B. E: interval between overshooting peaks of first and second action potential in trains of action potentials with a maximum number of action potentials for each cell was 103.8 ± 6.9 ms for WT (n = 11) and 104.3 ± 11.8 ms for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.96). F: action potential frequency (reciprocal of the interval time in E) was 10.5 ± 0.9 Hz for WT (n = 11) and 11.8 ± 1.6 Hz for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 13) (P = 0.34).

Na+ and K+ currents during the first action potential in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells.

Because deletion of Calhm1 decreased the half-width of a single action potential without affecting other action potential properties, we considered that CALHM1 may provide an additional component of the conductances during an action potential. To test this possibility, the voltage-gated transient currents during action potentials were estimated. The main contribution of voltage-gated Na+ and K+ currents to the action potentials in type II cells has been studied previously (Chen et al. 1996; Kimura et al. 2014; Noguchi et al. 2003). Expression of multiple voltage-gated Na+ channels (Gao et al. 2009) and K+ channels (Ohmoto et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2009) in type II cells allows precise control of the action potential properties and firing frequency. To analyze the ionic currents during action potentials, we found that use of acutely isolated healthy single taste bud cells was essential. In our current study, whole cell clamping was performed in the Pulse program (HEKA), which lacks the capability to use the action potential from a recorded cell as the voltage command waveform to elicit currents in the same single cell. Nevertheless, the voltage-gated transient currents during action potentials can be estimated. For action potentials recorded under conditions of no or small current injections, the net ionic current through the membrane is approximately equal and opposite to the capacitance current, expressed as Iionic = −CmdV/dt, where Iionic is the net ionic current, Cm is the cell capacitance, and dV/dt is the first time derivative of the action potential (Bean 2007; Hodgkin and Huxley 1952; Taddese and Bean 2002). Phase-plane plots of the first time derivative of the first action potential (dV/dt) vs. the voltage are shown in Fig. 6B. There were large transient inward Na+ currents and outward currents during the first action potential for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (red traces in Fig. 6A). The estimated Na+ current rapidly reached a maximum inward peak at ~20 mV of −180 pA with an activation time constant of 1.10 ms for this WT cell (cell capacitance: 5.0 pF) and −230 pA with an activation time constant of 0.95 ms for this Calhm1 KO cell (cell capacitance: 4.6 pF; Fig. 6, A and C). The average peak inward Na+ current was similar between WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 6D, left). The average time constant of Na+ current reaching the peak was ~1.0 ms for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 6D, right). These results suggest that CALHM1 does not contribute to the amplitude and kinetics of the Na+ currents during the first action potential, which is consistent with a lack of effect of CALHM1 expression on steady-state Na+ currents.

Fig. 6.

Phase-plane plots and inward Na+ and outward currents during the first action potential. A: action potentials recorded from WT (left; green trace) and Calhm1 KO type II cells (right; purple trace). Estimated voltage-gated currents [−C(dV/dt), where C is cell capacitance and V the membrane voltage] during action potentials are shown for WT and Calhm1 KO cells (red traces). B: dV/dt vs. voltage phase-plane plots during the action potentials in A and B. C: phase-plane plots of estimated currents [−C(dV/dt)] vs. voltage during action potentials in A for a WT (left) and a Calhm1 KO cell (right). D, left: estimated peak inward Na+ currents during the first action potential were −201.6 ± 26.8 pA for WT (n = 8) and −220.5 ± 31.7 pA for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) cells (P = 0.75). Right, activation time constants of Na+ currents (τNa) during first action potential were 1.10 ± 0.06 ms for WT (n = 8) and 1.03 ± 0.06 ms for Calhm1 cells KO (n = 7) (P = 0.35). E, left: estimated peak outward currents during the first action potential were 127.1 ± 14.4 pA for WT (n = 8) and 131.3 ± 12.4 pA for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) (P = 0.71). Right, activation time constant of outward currents (τoutward) during first action potential were 2.95 ± 0.23 ms for WT (n = 8) and 2.11 ± 0.16 ms for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) (**P < 0.005). Time constants were determined by fitting with single exponential functions. F: times between peak inward Na+ current and peak outward current were 3.8 ± 0.2 ms for WT (n = 8) and 3.2 ± 0.3 ms for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) (*P < 0.05).

The estimated transient outward current reached a maximum peak at 20 mV of 140 pA 3.4 ms after the inward Na+ current peak for the WT cell and 190 pA at 2.4 ms after the inward Na+ current peak for the Calhm1 KO cell (Fig. 6, A and C). The time constant of the estimated outward current deactivation from its peak to baseline was 2.6 ms for this WT cell and 1.7 ms for this Calhm1 KO cell. The average outward peak current was similar between WT cells and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 6E, left). Notably, the average time constant of outward current deactivation in WT cells (2.95 ± 0.23 ms, n = 8) was larger (P < 0.005) than that in Calhm1 KO cells (2.11 ± 0.16 ms, n = 7; Fig. 6E, right). The average time between peak inward Na+ and peak outward currents in WT cells (3.8 ± 0.2 ms, n = 8) was also longer (P < 0.05) than in Calhm1 KO cells (3.2 ± 0.3 ms, n = 7; Fig. 6F). Thus, although CALHM1 does not significantly contribute to the amplitude of the outward currents during action potentials, these results indicate that it contributes to their kinetics, delaying the time to peak and slowing their deactivation. These results suggest that CALHM1-associated channels contribute to the conductances during action potentials.

Na+ and K+ currents during action potential trains in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells.

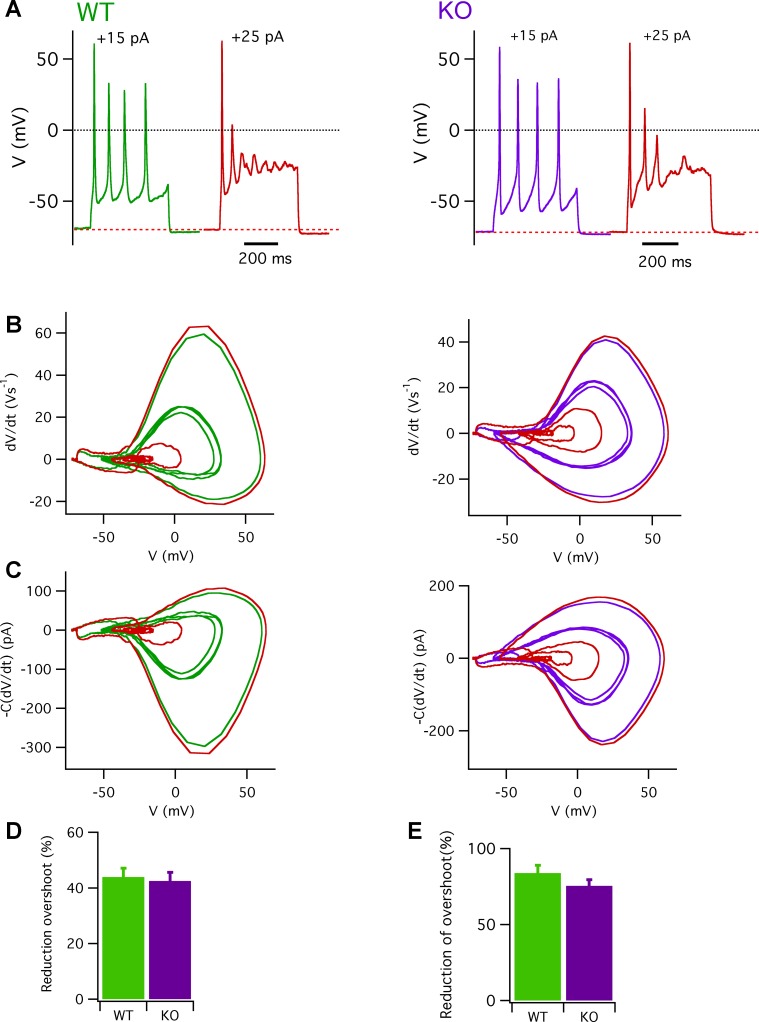

Phase-plane plots were also analyzed to estimate the Na+ and K+ currents during a train of action potentials (Fig. 7A). Phase-plane plots for trains of action potentials, in which four action potentials were triggered by a 15-pA depolarizing current injection in a WT cell (green trace) and a Calhm1 KO cell (purple trace) are shown in Fig. 7B. The phase-plane plot shows that the overshooting values of the second action potential in both cells were significantly reduced compared with those of the first action potential. However, the subsequent action potentials displayed overshooting values similar to those of the second action potential. The average overshooting peaks produced by the second action potential were reduced by ~43% for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 7D). The phase-plane plots of the estimated ionic currents (Fig. 7C) were consistent with the observed reduction of overshooting of action potentials following the first one. The peak inward Na+ current during the second action potential was strongly reduced and was achieved at a more hyperpolarized voltage compared with that of the first action potential. The outward current was also reduced after the first action potential, suggesting that the extent of K+ channel activation was dictated by the extent of Na+ channel-induced depolarization. The results indicate that type II taste bud cells can fire a train of action potentials in response to a mild electrical stimulus, but that deletion of CALHM1 has no obvious effects on the firing frequency.

Fig. 7.

Estimated currents during trains of action potentials in WT and Calhm1 KO type II cells. A: representative trains of action potentials (Ihold = −10 pA) for WT (left) and Calhm1 KO type II cells (right) elicited by current injections of 15 and 25 pA. Black dotted lines indicate 0 mV. Red dashed lines represent −71 mV for a WT cell and −72 mV for a Calhm1 KO cell. B: phase-plane plots of dV/dt vs. voltage during a train of action potentials for WT (left) and Calhm1 KO cells (right), with either 15-pA (green and purple) or 25-pA (red) current injections. C: phase-plane plots of estimated currents [−C(dV/dt)] vs. voltage during a train of action potentials, with color codes as in B, for a WT cell (left; capacitance = 5.0 pF) and a Calhm1 KO cell (right; capacitance = 5.6 pF). D: percent reduction of second action potential overshooting value, calculated as reduction (%) = [(overshoot1st – overshoot2nd)/overshoot1st × 100], was 43.9 ± 3.2% for WT (n = 8) and 42.5 ± 3.1% for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) (P = 0.79) under a mild electrical stimulus. With stronger depolarizing current injections, percent reductions were 83.9 ± 5.1% for WT (n = 8) and 75.5 ± 4.0% for Calhm1 KO cells (n = 7) (P = 0.31).

We also investigated the effects of stronger stimulation by using a more depolarizing current injection. Injection of 25 pA increased the firing frequency to 15 Hz from 10 Hz at 15 pA. Action potential traces in Fig. 7A and their phase-plane plots in Fig. 7B (red traces) indicate that overshooting of the second action potential was much more strongly reduced compared with that observed with 15-pA current injection. The overshoots of the second action potential were reduced by ~80% for both WT and Calhm1 KO cells (Fig. 7E).

The slow depolarization after the first action potential leading up to the second action potential is likely due to a Na+ current. This current between action potentials may be associated with partial recovery from Na+ channel inactivation. After the second action potential, Na+ channel inactivation and recovery from inactivation with mild stimuli achieved equilibrium, since the currents did not decrease further in subsequent action potentials. However, with stronger depolarizing current injections that enhanced action potential firing frequency, escape from Na+ channel inactivation was too slow to sustain action potential firing. Accordingly, type II cell taste cells can fire a repetitive action potential train with mild stimuli, whereas stronger stimulation limits the number of action potentials that the cells can generate. Deletion of CALHM1 did not alter the Na+ and K+ currents properties during repetitive action potential firing in response to either mild or strong electrical stimulations under the conditions of the current study.

DISCUSSION

A challenging question in peripheral taste perception is how action potentials generated during stimulation of type II cells activate nonselective voltage-gated channels to release ATP. With the recent identification of CALHM1 ion channel as an essential component of the ATP-release mechanism, a rigorous characterization of the membrane properties and action potential features under defined stimulation conditions in the presence and absence of CALHM1 expression is critical. In the current study, we systematically recorded action potentials and voltage-gated currents in the same single type II taste bud cells by switching between whole cell current- and voltage-clamp modes in acutely isolated cells using defined electrical stimuli. Whereas taste molecules may elicit different responses in cells in situ, the present studies provide a rigorous characterization by which in situ responses can be compared and interpreted. We have established the properties of the resting and active Na+ and K+ conductances and the roles of CALHM1 in in the electrical properties of type II cells. A major finding in the present study is that the steady-state voltage-gated outward currents with associated tail currents are completely absent in type II cells from Calhm1 KO mice, convincingly demonstrating that these voltage-gated currents are carried by CALHM1-associated channels. In addition, we found that CALHM1-associated channels in type II cells are closed at the resting membrane potentials and appear to be activated during action potentials generated by electrical stimulation.

Membrane properties in taste type II cells.

The resting membrane potential of taste bud cells has been reported over a large range from −70 to −40 mV, with most studies reporting between −40 and −50 mV (Bigiani et al. 1998; Medler et al. 2003; Roper 1983), although a few measured approximately −65 mV (Noguchi et al. 2003; Suwabe and Kitada 2004). In our present study, the resting membrane potential of type II cells was near −65 mV, a value that is similar to that of mouse cortical neurons (Ma et al. 2012). The resting membrane potential was strongly dependent on the daily preparations, indicating significant variability of the health of the isolated cells. Accordingly, we discarded recordings from cells with whole cell seal resistance of <1.5 GΩ at a holding potential of −70 mV. The injection current required to hold type II cells at −70 mV was not altered by knockout of Calhm1, in contrast to mouse cortical neurons, in which a larger injection current was required to hold Calhm1 KO vs WT cells at −75 mV (Ma et al. 2012). Furthermore, eliminating CALHM1 expression did not alter the resting membrane potential, indicating that CALHM1-associated channels do not contribute to the resting membrane conductance in type II cells.

Within the voltage range of −80 to −50 mV, two membrane input resistances were detected. Within −80 to −70 mV, input resistance was ~400 MΩ, consistent with some previous reports (McPheeters et al. 1994; Roper 1983), whereas it was ~1.5 GΩ within −70 to −50 mV, consistent with some other reports (Chen et al. 1996; McPheeters et al. 1994; Medler et al. 2003; Suwabe and Kitada 2004). This represents the first report of two conductance regimes in type II cells, with unexpectedly less input resistance at more strongly hyperpolarized potentials. Interestingly, the resting membrane potential sits near the transition of these two conductance regimes. Although Kir2.1 channels could contribute to taste cell conductance at potentials of −80 to −60 mV (Ye et al. 2016), it is unlikely that they contribute to the currents we measured because EK = −82 mV in our study. Their molecular basis therefore remains to be determined. The conductance at more depolarized voltages of −60 to −40 mV may be contributed by Na+ steady-state “persistent” currents that have been observed in this voltage range in neuronal cells (Bean 2007; French et al. 1990; Vervaeke et al. 2006). This steady-state persistent current in type II taste cells has been observed previously (Kimura et al. 2014; Romanov and Kolesnikov 2006), but it was thought to be a leak current (Kimura et al. 2014). However, this is unlikely because the I-V relation between −80 and −40 mV was not linear (Fig. 3E). This likely Na+ persistent current may contribute to the slow depolarization phase between action potentials. CALHM1-associated channels were not activated at membrane potentials from −80 to −50 mV, so they did not contribute to the membrane input resistance in this voltage range. The molecular basis of the persistent current remains to be identified in type II cells.

Membrane excitability of type II taste cells.

Taste bud cells generate action potentials in response to either electrical or tastant stimuli. In type II cells, it is generally agreed that action potentials are involved in activating the voltage-gated ATP release channels (Murata et al. 2010; Noguchi et al. 2003; Romanov et al. 2007, 2008; Taruno et al. 2013b), although it has been suggested that TRPM5 generator potentials are sufficient (Huang and Roper 2010). An outstanding question in peripheral taste transduction is how action potentials activate the nonselective voltage-gated channels to release ATP in type II cells. In the present study, we characterized membrane properties and action potential features in single type II cells. Unique in this study was the systematic application of current- and voltage-clamp modes to record action potentials and voltage-gated currents in the same single type II cells. In addition, we examined these properties in type II cells from both WT and Calhm1 KO mice to evaluate the influence of CALHM1 on these features. Type II cells fired action potentials generated by electrical stimulation at a threshold voltage of approximately −35 mV, overshooting to ~50 mV with ~2.5-ms half-width duration followed by an afterhyperpolarization to approximately −55 mV. We never observed type II cells to fire spontaneous action potentials at a holding potential of −70 mV. However, depolarization generated a train of action potentials with ~10-Hz firing frequency. By comparing the magnitudes and kinetics of the transient Na+ and K+ currents during action potentials with those of the steady-state voltage-gated currents, we can estimate that only 50% and 10% of all available Na+ and K+ channels, respectively, are activated during the first action potential under our conditions. Subsequent action potentials engaged ~25% of Na+ and ~5% of K+ channels available.

Deletion of Calhm1 reduced the time between the peak inward Na+ and peak outward currents during an action potential. In addition, deletion of Calhm1 accelerated the deactivation kinetics of the action potential transient outward current. These observations are consistent with activation of CALHM1-associated channels during an action potential (Romanov et al. 2007). Previous modeling of type II action potentials suggested that the presence of a nonselective tetraethylammonium-insensitive conductance would broaden the action potential and slow the membrane repolarization (Kimura et al. 2014), consistent with our observations that deletion of Calhm1 narrowed the width of the action potential and accelerated membrane repolarization. Our data therefore suggest that CALHM1-associated channels become at least partially activated during action potentials, but further studies are required to establish this more rigorously and to define the magnitude of the CALHM1-associated current activated during action potential firing.

We noticed that the CALHM1-associated currents ran down with time in some cells. We excluded cells from analyses if the recorded currents were >15% smaller after compared with before action potentials were recorded. CALHM1-associated current rundown was independent of the presence or absence of ATP, GTP, or Mg2+ in the pipette solution. CALHM1-associated current rundown may have influenced previous studies, since tail currents, shown in this study to be CALHM1 dependent, were either absent or minimal in some previous studies (Medler et al. 2003; Suwabe and Kitada 2004; Vandenbeuch et al. 2010).

Sustained and graded receptor potentials generated by tastants in situ were previously studied by intracellular recording (Akaike et al. 1976; Kimura and Beidler 1961; Tateda and Beidler 1964) and tastant-evoked action potentials in situ were studied by either loose- or tight-seal cell-attached patch clamp (Chang et al. 2010; Furue and Yoshii 1997; Murata et al. 2010; Varkevisser et al. 2001; Yoshida et al. 2005, 2006). Whereas these recordings revealed tastant-evoked responses, they did not record membrane conductances from the same cells. In contrast, action potentials elicited by electrical stimulation have been recorded by intracellular recording (Roper 1983) or by the whole cell patch clamp (Chen et al. 1996; Furue and Yoshii 1997; Kimura et al. 2014), but only one previous study recorded action potentials and whole cell conductances from the same single taste bud cell (Kimura et al. 2014). In the present study we have extended these studies to record action potentials and voltage-dependent conductances from the same type II cells, revealing important membrane properties in the presence and absence of the ATP release channel CALHM1. In the future, whole cell recordings, as we have performed, on identified type II cells in intact taste buds in normal and genetically modified animals in response to different taste molecules will provide deeper insights into the in situ electrical behavior of these cells.

In summary, we have established membrane properties of type II taste cells from both wild-type and Calhm1 knockout mice. Type II taste cells have two distinct regimes of membrane conductances. CALHM1 does not alter the resting membrane properties of these cells, unlike in mouse cortical neurons, but it accounts for the large nonselective voltage-gated currents that are a unique feature of type II cells, and it shapes action potentials by increasing their half-width duration.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders Grant DC012538 (to J. K. Foskett and Z. Ma).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.M. and J.K.F. conceived and designed research; Z.M. and W.T.S. performed experiments; Z.M. and W.T.S. analyzed data; Z.M., W.T.S., and J.K.F. interpreted results of experiments; Z.M. prepared figures; Z.M. and J.K.F. drafted manuscript; Z.M. and J.K.F. edited and revised manuscript; Z.M., W.T.S., and J.K.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address for J. K. Foskett: Department of Physiology, 700 Clinical Research Bldg., Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6085 (e-mail: foskett@mail.med.upenn.edu).

REFERENCES

- Akaike N, Noma A, Sato M. Electrical responses to frog taste cells to chemical stimuli. J Physiol 254: 87–107, 1976. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenet P, Lindemann B. Noninvasive recording of receptor cell action potentials and sustained currents from single taste buds maintained in the tongue: the response to mucosal NaCl and amiloride. J Membr Biol 124: 33–41, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF01871362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 451–465, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béhé P, DeSimone JA, Avenet P, Lindemann B. Membrane currents in taste cells of the rat fungiform papilla. Evidence for two types of Ca currents and inhibition of K currents by saccharin. J Gen Physiol 96: 1061–1084, 1990. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.5.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigiani A, Sbarbati A, Osculati F, Pietra P. Electrophysiological characterization of a putative supporting cell isolated from the frog taste disk. J Neurosci 18: 5136–5150, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RB, Waters H, Liman ER. A proton current drives action potentials in genetically identified sour taste cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 22320–22325, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013664107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sun XD, Herness S. Characteristics of action potentials and their underlying outward currents in rat taste receptor cells. J Neurophysiol 75: 820–831, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Medler KF, Damak S, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC. Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25. BMC Biol 4: 7, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreses-Werringloer U, Lambert JC, Vingtdeux V, Zhao H, Vais H, Siebert A, Jain A, Koppel J, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Pasquier F, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, Mann D, Lendon C, Campion D, Amouyel P, Davies P, Foskett JK, Campagne F, Marambaud P. A polymorphism in CALHM1 influences Ca2+ homeostasis, Aβ levels, and Alzheimer’s disease risk. Cell 133: 1149–1161, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French CR, Sah P, Buckett KJ, Gage PW. A voltage-dependent persistent sodium current in mammalian hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol 95: 1139–1157, 1990. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furue H, Yoshii K. In situ tight-seal recordings of taste substance-elicited action currents and voltage-gated Ba currents from single taste bud cells in the peeled epithelium of mouse tongue. Brain Res 776: 133–139, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00974-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N, Lu M, Echeverri F, Laita B, Kalabat D, Williams ME, Hevezi P, Zlotnik A, Moyer BD. Voltage-gated sodium channels in taste bud cells. BMC Neurosci 10: 20, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. The components of membrane conductance in the giant axon of Loligo. J Physiol 116: 473–496, 1952. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YA, Roper SD. Intracellular Ca2+ and TRPM5-mediated membrane depolarization produce ATP secretion from taste receptor cells. J Physiol 588: 2343–2350, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. The role of pannexin 1 hemichannels in ATP release and cell-cell communication in mouse taste buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6436–6441, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611280104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Beidler LM. Microelectrode study of taste receptors of rat and hamster. J Cell Comp Physiol 58: 131–139, 1961. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030580204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ohtubo Y, Tateno K, Takeuchi K, Kumazawa T, Yoshii K. Cell-type-dependent action potentials and voltage-gated currents in mouse fungiform taste buds. Eur J Neurosci 39: 24–34, 2014. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnamon SC, Finger TE. A taste for ATP: neurotransmission in taste buds. Front Cell Neurosci 7: 264, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Siebert AP, Cheung KH, Lee RJ, Johnson B, Cohen AS, Vingtdeux V, Marambaud P, Foskett JK. Calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) is the pore-forming subunit of an ion channel that mediates extracellular Ca2+ regulation of neuronal excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E1963–E1971, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204023109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Tanis JE, Taruno A, Foskett JK. Calcium homeostasis modulator (CALHM) ion channels. Pflugers Arch 468: 395–403, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00424-015-1757-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPheeters M, Barber AJ, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of light and dark cells isolated from mudpuppy taste buds. J Comp Neurol 346: 601–612, 1994. doi: 10.1002/cne.903460411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler KF. Honing in on the ATP release channel in taste cells. Chem Senses 40: 449–451, 2015. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler KF, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC. Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-gated currents in defined taste cell types of mice. J Neurosci 23: 2608–2617, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Yasuo T, Yoshida R, Obata K, Yanagawa Y, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. Action potential-enhanced ATP release from taste cells through hemichannels. J Neurophysiol 104: 896–901, 2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00414.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Ikeda Y, Miyajima M, Yoshii K. Voltage-gated channels involved in taste responses and characterizing taste bud cells in mouse soft palates. Brain Res 982: 241–259, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)03013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Misaka T, Abe K. Taste receptor cells express voltage-dependent potassium channels in a cell age-specific manner. Chem Senses 31: 739–746, 2006. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Kolesnikov SS. Electrophysiologically identified subpopulations of taste bud cells. Neurosci Lett 395: 249–254, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Bystrova MF, Jiang P, Margolskee RF, Kolesnikov SS. Afferent neurotransmission mediated by hemichannels in mammalian taste cells. EMBO J 26: 657–667, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Khokhlov AA, Kolesnikov SS. Voltage dependence of ATP secretion in mammalian taste cells. J Gen Physiol 132: 731–744, 2008. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper S. Regenerative impulses in taste cells. Science 220: 1311–1312, 1983. doi: 10.1126/science.6857254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert AP, Ma Z, Grevet JD, Demuro A, Parker I, Foskett JK. Structural and functional similarities of calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) ion channel with connexins, pannexins, and innexins. J Biol Chem 288: 6140–6153, 2013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwabe T, Kitada Y. Voltage-gated inward currents of morphologically identified cells of the frog taste disc. Chem Senses 29: 61–73, 2004. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddese A, Bean BP. Subthreshold sodium current from rapidly inactivating sodium channels drives spontaneous firing of tuberomammillary neurons. Neuron 33: 587–600, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taruno A, Matsumoto I, Ma Z, Marambaud P, Foskett JK. How do taste cells lacking synapses mediate neurotransmission? CALHM1, a voltage-gated ATP channel. Bioessays 35: 1111–1118, 2013a. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taruno A, Vingtdeux V, Ohmoto M, Ma Z, Dvoryanchikov G, Li A, Adrien L, Zhao H, Leung S, Abernethy M, Koppel J, Davies P, Civan MM, Chaudhari N, Matsumoto I, Hellekant G, Tordoff MG, Marambaud P, Foskett JK. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature 495: 223–226, 2013b. doi: 10.1038/nature11906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateda H, Beidler LM. The receptor potential of the taste cell of the rat. J Gen Physiol 47: 479–486, 1964. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordoff MG, Aleman TR, Ellis HT, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Shestopalov VI, Mitchell CH, Foskett JK, Poole RL. Normal taste acceptance and preference of PANX1 knockout mice. Chem Senses 40: 453–459, 2015. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Anderson CB, Kinnamon SC. Mice lacking pannexin 1 release ATP and respond normally to all taste qualities. Chem Senses 40: 461–467, 2015. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Kinnamon SC. Why do taste cells generate action potentials? J Biol 8: 42, 2009. doi: 10.1186/jbiol138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Zorec R, Kinnamon SC. Capacitance measurements of regulated exocytosis in mouse taste cells. J Neurosci 30: 14695–14701, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1570-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkevisser B, Peterson D, Ogura T, Kinnamon SC. Neural networks distinguish between taste qualities based on receptor cell population responses. Chem Senses 26: 499–505, 2001. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervaeke K, Hu H, Graham LJ, Storm JF. Contrasting effects of the persistent Na+ current on neuronal excitability and spike timing. Neuron 49: 257–270, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Iguchi N, Rong Q, Zhou M, Ogunkorode M, Inoue M, Pribitkin EA, Bachmanov AA, Margolskee RF, Pfeifer K, Huang L. Expression of the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ1 in mammalian taste bud cells and the effect of its null-mutation on taste preferences. J Comp Neurol 512: 384–398, 2009. doi: 10.1002/cne.21899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye W, Chang RB, Bushman JD, Tu YH, Mulhall EM, Wilson CE, Cooper AJ, Chick WS, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT, Kinnamon SC, Liman ER. The K+ channel KIR2.1 functions in tandem with proton influx to mediate sour taste transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E229–E238, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514282112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Sanematsu K, Shigemura N, Yasumatsu K, Ninomiya Y. Taste receptor cells responding with action potentials to taste stimuli and their molecular expression of taste related genes. Chem Senses 30, Suppl 1: i19–i20, 2005. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Shigemura N, Sanematsu K, Yasumatsu K, Ishizuka S, Ninomiya Y. Taste responsiveness of fungiform taste cells with action potentials. J Neurophysiol 96: 3088–3095, 2006. doi: 10.1152/jn.00409.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]