Abstract

Tuberculosis is one of the common causes of fever of unknown origin in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is more common in CKD patients, and is, unfortunately, often underdiagnosed despite extensive assessments. Recently, fluorine-18-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) has been available in the diagnosis of malignancy, inflammatory and infectious diseases, and has become a useful diagnostic tool. Here, we present two cases of endstage kidney disease who presented with fever of unknown origin at the time of dialysis initiation. In both cases, although interferon-gamma-releasing assay was positive, combined conventional diagnostic modalities such as computed tomography and gallium-citrate scintigraphy failed to detect the sites infected with tuberculosis. By contrast, extrapulmonary lesions were detected by FDG-PET/CT and successfully treated with combined anti-tuberculous drugs. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis was confirmed by biopsy of the affected lymph node and lumbar spine, followed by PCR of the biopsied specimen. These cases highlight the importance of considering tuberculosis as one of the differential diagnoses in pre-dialysis CKD patients with persistent fever, and the usefulness of FDG-PET/CT in the detection of infectious sites of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Dialysis initiation, Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Fever of unknown origin, Interferon-gamma-releasing assay, Positron emission tomography

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the common causes of fever of unknown origin in dialyzed and non-dialyzed chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients [1]. Recent clinical studies have shown that extrapulmonary TB is more common in CKD patients [2, 3]. The diagnosis of TB in CKD patients is often delayed because of their unspecific symptoms and negative tuberculin skin test results, reflecting impaired cellular immunity; host defenses against mycobacterial infection depend largely on cellular immunity [4, 5]. Diagnostic tools with high sensitivity and specificity are thus indispensable in the diagnosis of TB in CKD patients.

Recent advances in diagnostic tools and imaging techniques have drastically changed the diagnosis and management of TB [6]. Fluorine-18-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) has been used as a useful diagnostic tool in the detection of malignancy, inflammatory diseases and infectious diseases including TB [7]. In addition, interferon-gamma-releasing assay (IGRA) has emerged as a useful detection assay for active and latent TB, with higher sensitivity compared with the conventional diagnostic modalities [8].

Here, we report two cases of endstage kidney disease (ESKD) patients not on dialysis who presented with fever of unknown origin, and were finally diagnosed with extrapulmonary TB using IGRA, FDG-PET/CT and percutaneous biopsy and were successfully treated with anti-tuberculous drugs.

Case reports

Case 1

An 83-year-old woman with CKD stage G5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate: 6.0 mL/min/1.73 m2) received thorough review for persistent low-grade fever and lower back pain at our hospital. She had been treated with conservative treatment for CKD as an outpatient since she was 72-year old. The underlying kidney disease was hypertensive nephrosclerosis. She had a history of pulmonary TB, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and chronic urinary tract infection with multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli. She was initially diagnosed as having TB, contracted 15 years prior to admission, by computed tomography at another hospital. She did not receive anti-TB treatment at that time. She had a history of gastric carcinoma 10 years prior to admission. Her height was 163 cm and her body weight ranged between 45 and 47 kg. Her body mass index was ~17 kg/m2 for the last 5 years.

On admission, her body weight was 43 kg. She showed a relapsing fever (37–38 °C) and night sweating lasting for 6 months with slightly increased serum inflammatory markers, and high serum creatinine (Cr) and blood urea nitrogen levels. Laboratory data at presentation are shown in Table 1. Computed tomography did not show any lesions that could be causing the fever. Gallium-citrate scintigraphy showed no accumulation of the radioisotope in the whole body. IGRA (QuantiFERON-TB-Gold) was positive. Acid-fast stain of sputum did not reveal Mycobacterium. However, real-time PCR for TB was positive in one of the three distinct liquid cultures of sputum. An FDG-PET/CT was performed to determine the origin of the fever of unknown origin. An FDG-PET/CT disclosed the increased uptake of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose in the para-aortic lymph node, mesenteric lymph nodes and lumbar spine (Fig. 1a–d). Histology based on specimens obtained from a percutaneous lumbar spine biopsy showed recruitment of epithelioid cells and formation of multi-nucleated giant cells positive for CD68 without necrotic change (Fig. 2a–c), although Ziehl–Neelsen staining did not reveal acid-fast bacilli and fungus. However, the acid-fast culture of the biopsy specimen and sputum identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was finally diagnosed as having active TB of lumbar spondylitis and lymphadenitis.

Table 1.

Laboratory data at the time of diagnosis

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.1 | 8.8 |

| White blood cell (μL) | 8130 | 8050 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 78.5 | 58.2 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 11.3 | 27.1 |

| Platelet (μL) | 16.6 × 104 | 31.9 × 104 |

| Biochemistry | ||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.0 | 7.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 10 | 12 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 7 | 11 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 229 | 229 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | 9 | 22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 147 | 262 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 95 | 91 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 5.85 | 9.99 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 8.2 | 7.3 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 127 | 142 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 5.3 | 4.8 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 97 | 107 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.1 | 7.5 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 5.3 | 8.4 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 3.46 | 0.93 |

| Others | ||

| IGRA | Positive | Positive |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 6.0 | 5.7 |

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, IGRA interferon-gamma-releasing assay

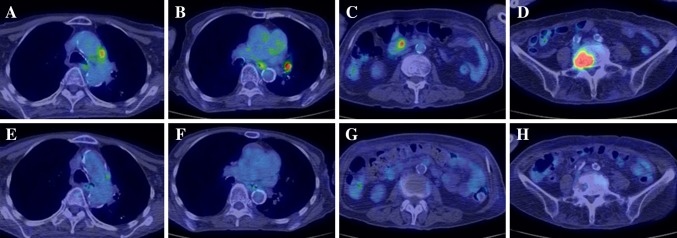

Fig. 1.

Images of 18-FDG-PET/CT before and after anti-tuberculosis treatment in Case 1. Images of 18-FDG-PET before treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs showing increased uptake in the para-aortic lymph node (a), mediastinal lymph node (b), mesenteric lymph node (c) and lumbar vertebra (d). Images of 18-FDG-PET after treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs showing disappearance of increased glucose uptake in the para-aortic lymph node (e), mediastinal lymph node (f), mesenteric lymph node (g) and lumbar vertebra (h). 18-FDG-PET/CT, fluorine-18-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography

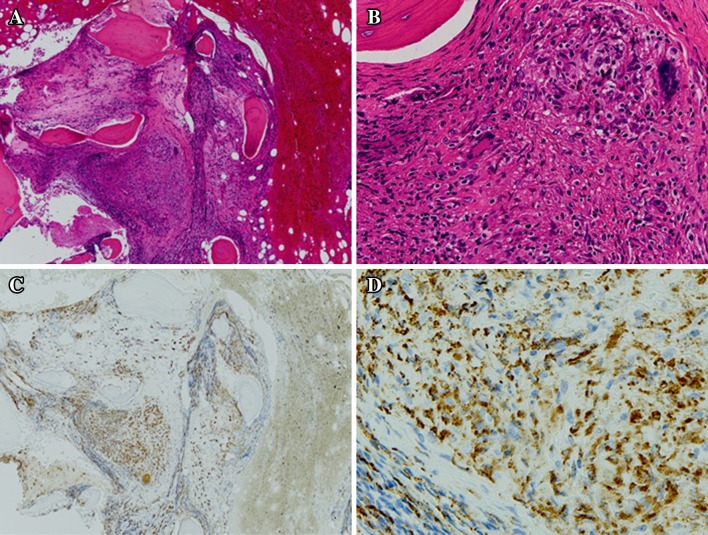

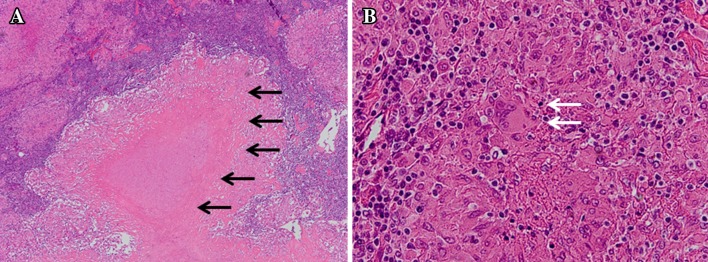

Fig. 2.

Histology of the lumber vertebra in Case 1. Hematoxylin–eosin staining of the epithelioid cell granuloma, consisting of many epithelioid cells and lymphocytes at a low magnification (original magnification ×40) and b high magnification (original magnification ×200). Caseous necrosis was not observed. Immunohistochemistry of epithelioid cells positive for CD68 at c low magnification (original magnification ×40) and d high magnification (original magnification ×200). Macrophage lineage cells are stained for CD68

Combination therapy with rifampicin, isoniazid and moxifloxacin for 2 months followed by 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid therapy was initiated, and the fever rapidly subsided. An FDG-PET/CT performed after 6 months of treatment revealed disappearance of increased fluorine-18-deoxyglucose uptake in the para-aortic lymph node, mesenteric lymph node, para-hilar lymph node and lumber spine (Fig. 1d–f). Fever did not relapse. Anti-TB treatment did not halt the progression of CKD. The slope of 1/Cr did not change significantly after treatment with anti-TB drugs. Eight months after anti-tuberculosis treatment, she started maintenance hemodialysis for ESKD and is now on dialysis without relapse.

Case 2

A 56-year-old man with CKD stage G5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate: 5.7 mL/min/1.73 m2) was hospitalized for persistent low-grade fever. He developed phlebitis of unknown etiology in the lower limbs at ages 34, 37 and 42. He received Y-graft replacement for an abdominal aortic aneurysm at age 47. At the time of operation, he was diagnosed as having CKD of unknown cause, and started to visit the nephrology department thereafter. At age 54, his serum Cr level was approximately 5 mg/dL. Two months prior to admission, he repeatedly developed a high fever (38.7 °C) that spontaneously subsided and showed a persistent increase in serum C-reactive protein levels (2.8–4.1 mg/dL) and ESKD (serum Cr: 9.6 mg/dL). Accordingly, he was hospitalized for evaluation of the persistent fever and for induction of renal replacement therapy for ESKD.

He showed a slight fever and slightly increased serum inflammatory markers with high serum Cr and blood urea nitrogen levels. Laboratory data at presentation are shown in Table 1. A chest X-ray and computed tomography did not show any lesions that could be causing the fever. Gallium-citrate scintigraphy showed no accumulation of the radioisotope throughout the body (Fig. 3a). An IGRA (QuantiFERON-TB-Gold) result was positive, although he did not have a previous history of TB. An FDG-PET/CT disclosed the increased uptake of fluorine-18-deoxyglucose in the bilateral cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 3b). Neck ultrasonography showed enlargement of bilateral lymph nodes (Fig. 3c). Histology based on specimens obtained from a percutaneous cervical lymph node biopsy showed recruitment of epithelioid cells and formation of multi-nucleated giant cells with caseous necrosis (Fig. 4a, b), although Ziehl–Neelsen staining did not reveal acid-fast bacilli and fungus. However, the acid-fast culture of the biopsy specimen detected Mycobacterium tuberculosis. He was finally diagnosed as having active tuberculous lymphadenitis.

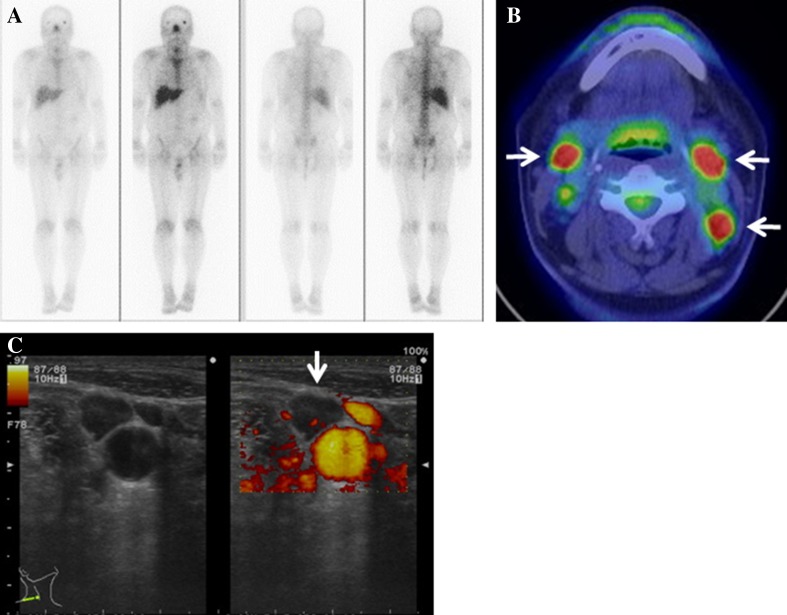

Fig. 3.

Imaging of multi-modality tests in Case 2. a Gallium-citrate scintigraphy showing no regional uptake of radionuclei. b 18-FGD-PET/CT with increased glucose uptake in the bilateral cervical lymph nodes (white arrows). c Ultrasonographic images of the enlargement of cervical lymph nodes without blood flow signal (white arrows). 18-FDG-PET/CT, fluorine-18-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography

Fig. 4.

Histopathology of the cervical lymph node in Case 2. a Caseous necrosis surrounded by granuloma consisting of inflammatory cells in the lymph node (black arrows) (original magnification ×50, hematoxylin–eosin staining). b Epithelioid cell granuloma consisting of many epithelioid cells, lymphocytes and multi-nucleated giant cells (white arrows) (original magnification ×200, hematoxylin–eosin staining)

Combination therapy with rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and streptomycin was initiated, and the fever disappeared. During hospitalization, he initiated maintenance hemodialysis therapy for ESKD and is now on dialysis without relapse.

Discussion

Here, we described two cases of pre-dialysis ESKD patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis or tuberculous spondylitis who presented with fever of unknown origin. In Case 1, para-aortic and mesenteric lymphadenitis and lumbar spine TB were detected by FDG-PET/CT and confirmed by lumber spine biopsy and PCR. In Case 2, cervical lymphadenitis was successfully detected by FDG-PET/CT and confirmed by histology and culture of the lymph node biopsy specimen. Histological findings of both cases showed granuloma consisting of epithelioid cells, indicating active TB. Both cases were successfully treated by a combination of anti-tuberculous drugs, followed by initiation of maintenance hemodialysis therapy for ESKD.

FDG-PET/CT has become a useful diagnostic tool for detecting the site of various diseases and rating disease activity [9, 10]. Because sampling from the infected sites and detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by culture or PCR are the cornerstones for the definite diagnosis of TB, localization of extrapulmonary TB is a critical issue. There are several imaging modalities, such as ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which rely significantly on morphological changes and fail to detect changes at molecular levels [11]. By contrast, an FDG-PET/CT can detect increased glucose metabolism at molecular levels and can identify multiple occult foci of TB involvement in a single study and lead to prompt and accurate diagnosis [12]. Although an FDG-PET/CT does have several limitations, such as high cost, low availability, and confounding by diabetes mellitus, FDG-PET/CT provides substantial benefits for CKD patients with fever of unknown origin including extrapulmonary TB.

Among the several diagnostic modalities for active TB, IGRA has been increasingly used in patients suspected of active TB [13]. A tuberculin skin test, which is often used in the general population, is less useful in hemodialysis patients because impaired cellular immunity yields a high prevalence of false-negative results [3–5]. The principle behind IGRA is to quantitatively assess activation of monocytes by measuring the amount of interferon-gamma released from CD4-positive lymphocytes exposed to specific antigens that are related to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: early secreted antigen target 6 and culture filtrate protein 10 [14]. Importantly, IGRA does not respond to other mycobacterium species, even Bacille Calmette–Guerin, enabling the use of IGRA instead of the tuberculin skin test for patients previously vaccinated with Bacille Calmette–Guerin.

One of the major drawbacks of IGRA is that IGRA cannot distinguish active TB from latent TB infection based on its mechanism [13]. In a strict sense, a positive result with IGRA indicates either active TB or latent TB. In this regard, positive results of IGRA do not confirm diagnosis of acute TB infection. Thus, the gold standard diagnosis is still the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by culture or PCR using infected samples [8, 15]. In the present case, both patients were negative for tuberculin skin tests, while IGRA was positive, suggesting that the attending physicians consider the possibility of active TB as the potential cause of the fever of unknown origin, although a positive result with IGRA does not confirm the presence of active TB. The sensitivity of IGRA is much higher than that of the tuberculin skin test, making IGRA a more useful supplementary tool in the diagnosis of active TB [13, 16].

TB is a very important cause of fever of unknown origin in CKD patients [1, 13, 17]. TB has now been considered as the re-emerging infection worldwide. The prevalence of latent TB is extremely high in pre-dialysis and dialysis CKD patients [13, 18].

Extrapulmonary TB is more common in CKD patients, although the reason remains unclear. Because extrapulmonary TB often accompanies non-specific signs and symptoms, it is often undiagnosed and leads to delayed diagnosis, followed by deterioration in the patient’s nutritional status [13, 19]. In the present cases, both patients showed non-specific symptoms including fever, body weight loss, loss of appetite and night sweats, and these symptoms did not directly identify the cause. Physicians should consider the possibility of extrapulmonary TB when they encounter patients suffering from these above-mentioned non-specific symptoms.

It remains unknown why TB is often reactivated or newly infectious at the time of dialysis initiation. Several studies have reported that more than half hemodialysis patients were diagnosed with TB within 1 year after hemodialysis initiation [17]. A reason may be that the impairment of cellular immunity reaches its maximum at the time of dialysis initiation, because cellular immunity plays important roles as a defense system for organisms living in intracellular spaces, like TB [4, 5]. In CKD, the cellular immune system is shown to be partly impaired by retention of uremic toxin, as evidenced by attenuation of tuberculin skin test [15, 20]. Serum calcitriol, which is important for macrophage lineage cells in the prevention of TB reactivation, decreases in patients with CKD, especially in ESKD patients [21]. Once renal replacement therapy is initiated, retention of uremic toxin gradually attenuates, cellular immunity slightly improves, and the use of calcitriol or its derivative may increase for controlling secondary hyperparathyroidism. Accordingly, we speculate that the risk of developing active TB or reactivation of TB reaches its peak around the time of dialysis initiation.

The contribution made by other important risk factors other than CKD to the recurrence of TB is an important topic of debate. Previous reports have shown that age, old tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, CKD, infliximab therapy, poorly controlled diabetes, silicosis, underweight and gastrectomy are relative risks of reactivation of TB [22]. Most of these risk factors are closely associated with impairment of the host immune system. Gastrectomy may be related to impaired immunity through malnutrition. Among these risk factors, our case was complicated by the patient being underweight and having had a gastrectomy. Because our patient had suffered from several diseases, including pulmonary invasive aspergillosis, CKD, chronic urinary tract infection and distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer, these co-morbidities might have promoted sustained malnutrition, finally contributing to the recurrence of TB.

Previous studies have shown that TB occasionally involves the kidneys directly; for example, tubulointerstitial nephritis and glomerulonephritis [23]. Treatment with anti-TB drugs improves kidney function in patients with renal tuberculosis [24]. In the present cases, FDG-PET did not show hot spots in the bilateral kidneys, indicating that TB did not involve the kidneys. Kidney function did not improve after treatment with anti-TB drugs, although fever subsided and general conditions improved. Furthermore, the progression of CKD did not accelerate after TB treatment, although some anti-TB drugs can induce kidney dysfunction [25]. These results indicate that TB did not involve the kidneys and TB treatment did not affect the progression of CKD in our cases.

In summary, we report two cases of ESKD patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis and lumber spine TB which were successfully detected by FDG-PET/CT, and the diagnosis of active TB was confirmed by histology and culture of infected specimens. While the routine utilization of FDG-PET/CT cannot be justified owing to its limited availability and high costs, combined FDG-PET/CT and IGRA can serve as powerful supplementary tool in the early diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB in CKD patients with fever of unknown origin.

Conflict of interest

Honoraria: Kazuhiko Tsuruya (Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.), Research funding: Kazuhiko Tsuruya (Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries, MSD K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.), Endowed department: Kazuhiko Tsuruya (Baxter).

References

- 1.Okada R, Yuzawa Y, Kawamura T, Hamajima N, Watanabe Y, Matsuo S. Incidence of fever of unknown origin and subsequent antitubercular medications in hemodialysis patients: a two-year prospective study. Ren Fail. 2009;31:863–868. doi: 10.3109/08860220903216048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussein MM, Mooij JM, Roujouleh H. Tuberculosis and chronic renal disease. Semin Dial. 2003;16:38–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139X.2003.03010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson RM. The diagnosis of tuberculosis in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2012;25:419–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2012.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Descamps-Latscha B, Chatenoud L. T cells and B cells in chronic renal failure. Semin Nephrol. 1996;16:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girndt M, Sester U, Sester M, Kaul H, Kohler H. Impaired cellular immune function in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2807–2810. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.12.2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallis RS, Pai M, Menzies D, Doherty TM, Walzl G, Perkins MD, Zumla A. Biomarkers and diagnostics for tuberculosis: progress, needs, and translation into practice. Lancet. 2010;375:1920–1937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ataergin S, Arslan N, Ozet A, Ozguven MA. Abnormal FDG uptake on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with cancer diagnosis: case reports of tuberculous lymphadenitis. Intern Med. 2009;48:115–119. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR, Ling D, Menzies D, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Fielding K, Wilkinson RJ, Pai M. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70210-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugawara Y, Braun DK, Kison PV, Russo JE, Zasadny KR, Wahl RL. Rapid detection of human infections with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: preliminary results. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:1238–1243. doi: 10.1007/s002590050290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimizuka Y, Ishii M, Murakami K, Ishioka K, Yagi K, Ishii K, Watanabe K, Soejima K, Betsuyaku T, Hasegawa N. A case of skeletal tuberculosis and psoas abscess: disease activity evaluated using (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. BMC Med Imaging. 2013;13:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Souza MM, Sharma R, Tripathi M, Mondal A. F-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in tuberculosis of the hip: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Nucl Med. 2011;26:31–33. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.84610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kälicke T, Schmitz A, Risse JH, Arens S, Keller E, Hansis M, Schmitt O, Biersack HJ, Grünwald F. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET in infectious bone diseases: results of histologically confirmed cases. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:524–528. doi: 10.1007/s002590050538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue T, Nakamura T, Katsuma A, Masumoto S, Minami E, Katagiri D, Hoshino T, Shibata M, Tada M, Hinoshita F. The value of QuantiFERON TB-Gold in the diagnosis of tuberculosis among dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2252–2257. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobashi Y, Mouri K, Obase Y, Fukuda M, Miyashita N, Oka M. Clinical evaluation of QuantiFERON TB-2G test for immunocompromised patients. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:945–950. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segall L, Covic A. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in dialysis patients: current strategy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1114–1122. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09231209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue T, Nangaku M, Hinoshita F. Tuberculous lymphadenitis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and IFN-γ release assay. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:1221. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussein MM, Bakir N, Roujouleh H. Tuberculosis in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:584–587. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.8.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkata RK, Kumar S, Krishna RP, Kumar SB, Padmanabhan S, Kumar S. Tuberculosis in chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2007;67:217–220. doi: 10.5414/CNP67217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taskapan H, Utas C, Oymak FS, Gülmez I, Ozesmi M. The outcome of tuberculosis in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson RJ, Llewelyn M, Toossi Z, Patel P, Pasvol G, Lalvani A, Wright D, Latif M, Davidson RN. Influence of vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D receptor polymorphisms on tuberculosis among Gujarati Asians in west London: a case–control study. Lancet. 2000;355:618–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaziri ND, Pahl MV, Crum A, Norris K. Effect of uremia on structure and function of immune system. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:149–156. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horsburgh CR., Jr Priorities for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2060–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa031667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eastwood JB, Corbishley CM, Grange JM. Tuberculosis and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(6):1307–1314. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1261307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapagain A, Dobbie H, Sheaff M, Yaqoob MM. Presentation, diagnosis, and treatment outcome of tuberculous-mediated tubulointerstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2011;79:671–677. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vriese AS, Robbrecht DL, Vanholder RC, Vogelaers DP, Lameire NH. Rifampicin-associated acute renal failure: pathophysiologic, immunologic, and clinical features. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:108–115. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9428460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]