Abstract

Glioma is one of the most common, rapidly progressive and fatal brain tumors, and accumulating evidence shows that microRNAs (miRNAs) play important roles in the development of cancers, including glioma. Therapeutic applications of miRNAs in Ras-driven glioma have been proposed; however, their specific functions and mechanisms are poorly understood. Here, we report that miR-1301-3p directly targets the neuroblastoma Ras viral oncogene homolog (N-Ras) and functions as a tumor-suppressor in glioma. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was applied to detect the expression of miR-1301-3p in glioma specimens. The direct target genes of miR-1301-3p were predicted by bioinformatic analysis and further verified by immunoblotting and luciferase assays. The effects of miR-1301-3p on the proliferation and cell cycle of glioma cells were analyzed by cell-counting kit 8, colony formation, 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EDU) and flow cytometry assays. A xenograft model was used to study the effect of miR-1301-3p on tumor growth and angiogenesis. The expression levels of miR-1301-3p in glioma specimens were significantly downregulated. N-Ras was confirmed as a direct target of miR-1301-3p. MiR-1301-3p inhibited glioma cell growth and blocked the cell cycle to G1 by negatively regulating N-Ras and its downstream signaling pathway, MEK-ERK1/2. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of miR-1301-3p could be rescued by the overexpression of N-Ras. The protein levels of N-Ras were up-regulated in clinical glioma specimens and were negatively correlated with miR-1301-3p expression levels (r=-056, P=0.0002). In vivo studies revealed that increased levels of miR-1301-3p delayed the growth of intracranial tumors, which was accompanied by decreased Ki67 and CD31 expression. Taken together, our results demonstrate that miR-1301-3p plays a significant role in inactivating the Ras signaling pathway through the inhibition of N-Ras, which may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for treatment of glioma and other Ras-driven cancers.

Keywords: miR-1301-3p, N-Ras, proliferation, glioma

Introduction

Gliomas are the most frequent primary tumors that arise in the brain. The most malignant form of glioma, glioblastoma multiforme (GBM, grade IV), is one of the most aggressive human cancers and is a challenging disease to treat [1]. Although the current standard therapeutic strategy, which includes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, has been widely used, the median survival time of patients with GBM is still only 15 months [2,3]. The rapid growth of glioblastoma is a result of genomic instability and dysregulation of gene expression [4,5]. Moreover, because of our poor understanding of this cancer’s pathogenesis, therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma are limited [6,7]. Studying the molecular implications of genetic alterations underlying the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma should aid in the development of new diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic approaches.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small endogenous noncoding RNAs with lengths of approximately 18-23 nucleotides. They regulate gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level by completely or incompletely binding to the 3’-UTR (untranslated region) of their target messenger RNA (mRNA), and then repress translation or promote degradation of the mRNA to exert biological functions [8,9]. MiRNAs have pivotal roles in regulating important cellular functions such as proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, death, stress response, differentiation, and development. Dysregulation of miRNAs has been suggested to be associated with a variety of disorders, particularly cancers [10,11]. Moreover, miRNAs have been shown to be useful as diagnostic and prognostic indicators of disease type and severity [12-14]. Accumulating evidence has indicated that a subset of miRNAs are deregulated in gliomas [15-18], and our preliminary experiments show that miR-1301-3p is one of them. However, the role and mechanism of miR-1301-3p in glioma has not been reported so far.

RAS sarcoma (Ras) proteins are highly homologous small G proteins with GTPase activity that mediate cellular responses to external growth stimuli by signaling via different effector cascades [19]. Kirsten Ras (K-Ras), neuroblastoma Ras viral oncogene homolog (N-Ras), and Harvey Ras (H-Ras) represent the prototype members of the family of small G proteins that are the most frequently activated oncogenes in human cancers [20-23]. N-Ras is implicated and functionally altered in a number of cancers including glioma and has potential roles in the regulation of cancer cell growth, survival, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis [24,25]. Enhanced expression of the N-Ras gene by disrupted transcription may be a factor in the progression of glioma [26]. The major mechanism of N-Ras-induced oncogenic transformation is related to enhanced mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) pathway signaling caused by Ras-dependent activation of Raf serine/threonine-specific kinases. In addition, signal transduction via other pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways, are also critical [27-30]. Thus, N-Ras silencing has become an efficient therapeutic strategy in glioma, but it is still far from optimal and novel therapeutic strategies are needed urgently.

In the present study, we found that the expression of miR-1301-3p correlated with WHO grade and was down-regulated in clinical GBM samples. Moreover, we identified N-Ras mRNA as a direct target of miR-1301-3p, which was up-regulated in GBM tissues, and that the levels miR-1301-3p inversely correlated with those of N-Ras. We then sought to understand: (i) what are the roles of miR-1301-3p in tumor growth; (ii) the potential direct target of miR-1301-3p that may be involved in glioma development; (iii) whether miR-1301-3p overexpression inhibits MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathways via its direct target; (iv) the role miR-1301-3p has in glioma cell growth in nude mice. Generally speaking, the answers of these questions will provide new insights into the molecular mechanism of glioma development and will help develop a unique miRNA-based therapy for GBM management.

Materials and methods

Human tissue samples

Glioma specimens (low grade =15, high grade =18) and non-cancerous brain tissues (NBT) (n=6) were obtained from The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) approved the use of GBMs and non-cancerous brain tissues, and the procedures were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines. Permissions were obtained from participants, and patients granted informed consent. Gene expression profiling from four glioma cohorts of were used in this study. Microarray miRNA expression data for 158 gliomas were downloaded from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) data portal (http://www.cgga.org.cn/portal.php). The samples included 48 astrocytomas (A, WHO Grade II), 13 oligodendrogliomas (O, WHO Grade II), 8 anaplastic astrocytomas (AA, WHO Grade III), 10 anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (AO, WHO Grade IV), 15 anaplastic oligoastrocytomas (AOA, WHO Grade III), and 64 GBMs (WHO Grade IV). Microarray mRNA expression data for 216 gliomas were downloaded from the CGGA, which included 97 WHO II, 34 WHO III, 89 GBMs. Gene expression data (27 WHO II and III, 595 GBMs) were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/). Gene expression profiling data for 153 glioma samples were collected from GSE4290 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc= GSE4290), including 44 WHO II, 31 WHO III and 77 GBMs. Gene expression profiling data for 284 glioma samples were collected from GSE16011 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=+GSE16011), including 8 WHO I, 24 WHO II, 85 WHO III and 159 GBMs.

Cell culture and antibodies

Human GBM cell lines U87, U251, U118, LN229, A172, and H4 were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China), and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units of penicillin/mL, and 100 ng of streptomycin/mL. Normal human astrocytes (NHAs) were obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured in the provided astrocyte growth media supplemented with rhEGF, insulin, ascorbic acid, GA-1000, L-glutamine and, 5% FBS. All the cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Antibodies against mammalian MEK, p-MEK, ERK, p-ERK, CyclinE1, CDK2, CDC2 and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA). Antibodies against N-Ras, H-Ras and K-Ras were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Oligonucleotides, plasmid construction, and transfection

Hsa-miR-1301-3p mimic and hsa-miR-ctrl were chemically synthesized by Ribobio (Guangzhou, China). Small interfering (Si)N-Ras and control si-non-coding (siNC) oligonucleotides were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). A plasmid containing the human N-Ras coding sequence was constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Genechem; Shanghai, China). A human N-Ras cDNA was inserted into the vector, pGL3, to generate pGL3-N-Ras. All oligonucleotides and plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lentiviral packaging and establishment of stably transduced cell lines

A lentiviral packaging kit was purchased from Genechem (Shanghai, China). A lentivirus carrying hsa-miR-1301-3p or hsa-miR-negative control (miR-ctrl) was packaged in the human embryonic kidney cell line, 293T, and the virions were collected according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stable cell lines were established by infecting U87 cells and U251 cells with lentiviruses, followed by puromycin selection.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was isolated from harvested cells or human tissues with Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, CA, USA). A stem-loop-specific primer method was used to measure the expression levels of miR-1301-3p, as described previously [31,32]. Expression of U6 was used as an endogenous control [33]. The cDNAs were amplified by qRT-PCR using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara) on a 7900HT system, Primers were purchased from Ribobio. And fold changes were calculated by relative quantification (2-ΔΔCt).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously [34]. Briefly, Cells or tissues were lysed on ice for 30 min in radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA, and 10 mM NaF) supplemented with 1 mM sodium vanadate, 2 mM leupeptin, 2 mM aprotinin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 mM pepstatin A. The lysates were centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min, the supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (KenGEN, Jiangsu, China). Protein extracts were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) in transfer buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM glycine, 20% [volume/volume] methanol). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies. An electrochemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for signal detection.

Cell proliferation assay

For the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, stabled transfected U251 and U87-MG cells were seeded in 96-well plates, and then cells were cultured for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h before performing the CCK-8 assay (Dojindo, Japan). After a 1 h incubation with CCK-8 at 37°C, absorbance (OD value) at a wave length of 450 nm was detected and used for calculating cell viability.

For the colony formation assay, cells were harvested 24 h after transfection and then seeded in a new six-well plate (200 cells/well) and cultured for approximately 2 weeks until colony formation was observed. Colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma, USA). A colony was considered to be 450 cells. Colony formation rate was used to calculate post-transfection cell survival rate.

For the 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EDU) proliferation assay, the Cell-Light EDU imaging detection kit was purchased from Life Technologies (MA, USA). Cells which had been transfected 48 h previously were incubated with 10 μM EDU for 24 h, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with both the Alexa-Fluor 594 reaction cocktail for EDU and Hoechst 33342 for cell nuclei, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Finally, samples were imaged under a fluorescent microscope.

Flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle

The glioma cells from each group were cultured in six-well plates, trypsinized at 48 h after transfection of lentivirus and/or plasmids, and then collected by centrifugation for five minutes at 1500 r/minute. The cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), collected by centrifugation and ruptured in 70% alcohol overnight. The supernatant was discarded after centrifuging. The cells were washed with PBS, stained using a Cell Cycle Staining Kit (Multi Sciences, Hangzhou, China), and incubated for 30 minutes in the dark before being analyzed by flow cytometry.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

The wild-type (WT) and mutated (Mut) putative miR-1301-3p seed matching sites in the N-Ras 3’-UTR and cloned into the SacI and HindIII sites of the pmiRNA-Report vector (Genechem, Shanghai, China). U87 and U251 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and cotransfected with the WT or Mut reporter plasmid, a Renilla luciferase (pRL) plasmid, and the miR-1301-3p mimic or miR-ctrl. Luciferase activities were analyzed 24 h after transfection using the Promega Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (WI, USA).

Nude mouse model of intracranial glioma

BALB/c-A nude mice at 4 weeks of age were purchased from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We investigated the therapeutic potential of miRNA-1301-3p using U87 glioma cells in a xenograft model. The mice were randomly assigned into two groups and intracranially implanted with 5×105 U87 cells (pretreated with lentivirus containing the miRNA-1301-3p or negative control sequences) using a stereotactic instrument. Bioluminescence imaging was used to detect intracranial tumor growth. The mice were anesthetized, injected intraperitoneally with D-luciferin at 50 mg/mL and imaged with the IVIS Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences) for 10-120 s. The Living Images software package (Caliper Life Sciences) was used to determine the integrated flux of photons (photons per second) within each region. Additionally, the overall survival of the mice was monitored during the experimental period. Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) of brain specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and used for immunohistochemistry. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Management Rule of the Chinese Ministry of Health (document 55, 2001) and were conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines and experimental protocols of Nanjing Medical University.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining

For HE staining, brain tissue sections (5 μm) embedded in paraffin blocks were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in alcohol and distilled water. The samples were washed in PBS for 5 min three times each and stained with hematoxylin (USA, Sigma) for 5 min. To observe the clarity of nuclei and cytoplasm under the microscope, sections were stained with eosin (USA, Sigma) for 2 min. After conventional dehydration and sealing, images were observed and collected under a microscope.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry to detect CD31 and Ki-67 (Cell Signaling Technology MA, USA) in nude mouse xenograft tumor tissues was performed as described previously [35].

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

The expression of miR-1301-3p in GBM samples and NBTs was detected by FISH. The mature human miR-1301-3p sequence is: 3’-CUUCAGUGAGGGUCCGUCGACGUU-5’. We used (LNA)-based probes directed against the full length mature miRNA sequence. The 5’-FAM-labelled miR-1301-3p probe sequence is: 5’-GAAGTCACTCCCAGGCAGCTGCAA-3’, and was purchased from BioSense (Guangzhou, China). The FISH procedure followed the BioSense instructions. Briefly, frozen sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then washed twice with PBS. Fixed slides were then treated with proteinase K at 37°C for 10 min, followed by dehydration in 70%, 85% and 100% ethanol for 5 min. The probe was then added to the slides, which were denatured at 78°C for 5 min. Hybridization was then carried out overnight at 42°C in a humid chamber. The next day, post-hybridization washes were performed with 50% formamide with 2×SSC at 43°C, followed by 2×SSC washes at room temperature to remove non-specific and repetitive RNA hybridization. Finally, slides were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma) for 10 min and examined with a Zeiss LSM 700 Meta confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed three times, and all values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The correlations between miR-1301-3p expression and N-Ras levels in glioma tissues were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed using GraphPad 5.0 software. Statistical evaluation of data was determined using the t test. The differences were considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

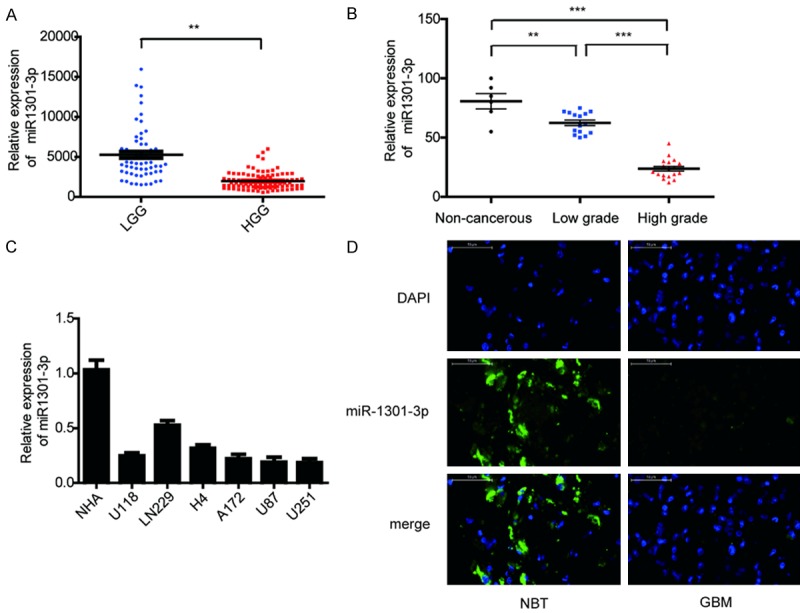

MiR-1301-3p is down-regulated in glioma tissues and cell lines

To investigate miRNA expression in human glioma tissues, miR-1301-3p expression was analyzed in 158 glioma tissues based on the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) data, and we found that miR-1301-3p expression was significantly lower in high grade gliomas (HGG) compared to low grade gliomas (LGG) (Figure 1A). We then evaluated the expression level of miR-1301-3p in 33 different grades of glioma tissues and in six non-cancerous brain tissues by qRT-PCR. The data indicated that the expression level of miR-1301-3p was significantly lower in glioma tissues compared to non-cancerous brain tissues. Moreover, the decrease was more pronounced in high-grade gliomas (grade III and IV) compared to low-grade gliomas (grades I and II) (Figure 1B). In addition, we found that miR-1301-3p was also decreased in the glioma cell lines U118, LN229, H4, A172, U87 and U251, especially in U87 and U251 cells (Figure 1C). We then chosed one representative GBM specimen and the non-cancerous brain tissues for FISH analysis, and we drew a consistent result (Figure 1D). In general, these data suggested that miR-1301-3p was down-regulated in glioma tissues and cell lines and the expression level was negatively correlated with the grade of glioma.

Figure 1.

Down-regulation of miR-1301-3p in glioma tissues and glioma cell lines. A. CGGA database showing reduced miR-1301-3p expression in high-grade glioma tissues compared with that in low-grade glioma tissues. B. The expression of miR-1301-3p in 6 non-cancerous brain tissues, 15 low-grade glioma tissues and 18 high-grade glioma tissues was measured by real-time PCR, miR-1301-3p levels in normal brain tissues were indeed higher than in glioma specimens, and were significantly decreased with ascending pathological grade of tumor. C. The expression of miR-1301-3p in normal human astrocytes (NHAs) and six glioma cell lines (U118, LN229, H4, A172, U87 and U251). D. The expression of miR-1301-3p in NBT and GBM specimens was assessed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (scale bars, 50 μm).

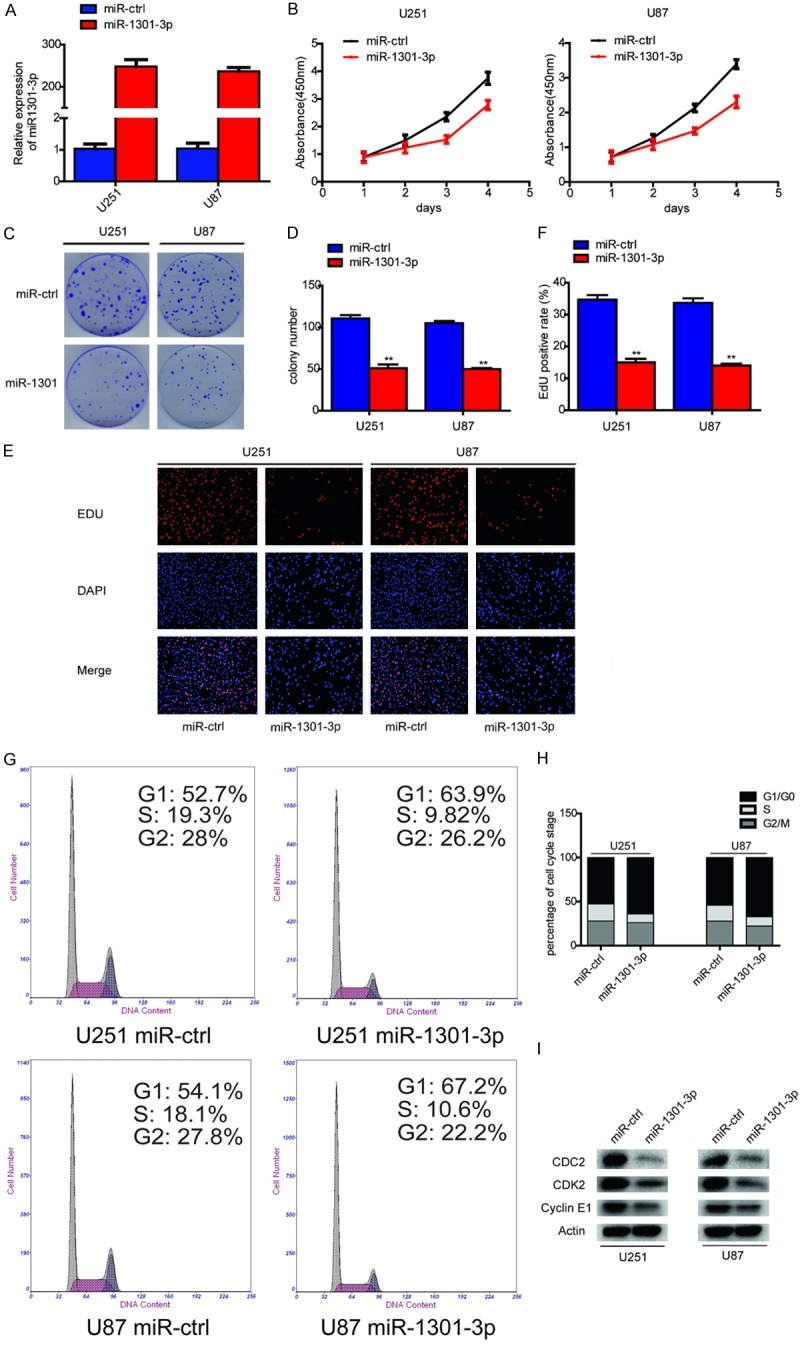

Critical role of miR-1301-3p in glioma cell proliferation

The abnormal expression of miR-1301-3p led us to investigate its biological roles in glioma. Specially constructed lentivirus for miR-1301-3p was transfected into U251 and U87-MG cells to alter the expression level of miR-1301-3p. qRT-PCR demonstrated that miR-1301-3p was significantly increased compared to negative control groups (Figure 2A). The CCK-8 assay was used to assess short-term cell viability. As shown in Figure 2B, miR-1301-3p strongly inhibited cell viability compared to the control group. Furthermore, the colony formation assay found that glioma cells transfected with lentivirus miR-1301-3p always exhibited significantly fewer and smaller colonies compared with those transfected with the miR-ctrl (Figure 2C and 2D). This observation illustrated that miR-1301-3p can suppress long-term glioma cell proliferation. To more objectively evaluate the effect of miR-1301-3p on proliferation, EDU incorporation experiments were performed, the results showed that miR-1301-3p significantly decreased the EDU-positive rate in both U251 and U87-MG cells (Figure 2E and 2F). Because a reduction in cell proliferation ability often accompanies changes in cell cycle progression, we next investigated the cell cycle distribution of cells overexpressing miR-1301-3p. Flow cytometry analysis showed that overexpression of miR-1301-3p increased the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase and decreased the percentage of cells in the S and G2/M phases (Figure 2G and 2H). Meanwhile, western blotting indicated that the expression of cell cycle-related proteins, cyclinE1, CDK2 and CDC2 were reduced dramatically after transfection with miR-1301-3p compared with miR-ctrl (Figure 2I). Taken together, these data suggested that miR-1301-3p acts as anti-oncogene in glioma cells.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of miR-1301-3p inhibits glioma cell proliferation in vitro. A. The relative expression of miR-1301-3p in U251 and U87-MG cells was analyzed by qRT-PCR after transfection. B. Proliferation was determined using the CCK-8 assay following culture for 96 h. Data are presented as the means of triplicate experiments. C, D. Long-term cell viability was evaluated using the colony formation assay. Data are presented as the means of triplicate experiments. E, F. Proliferating cells were examined using the EDU assay. Representative images are shown (original magnification, 200×). (**P<0.01). G, H. The cell cycle phase of U251 and U87-MG cells transfected with miR-1301-3p or negative control (miR-ctrl) lentivirus was analyzed by flow cytometry. I. Western blot analysis of CDC2, CDK2 and cyclinE1 in U251 and U87-MG cells 48 h after transfection. β-Actin served as the loading control.

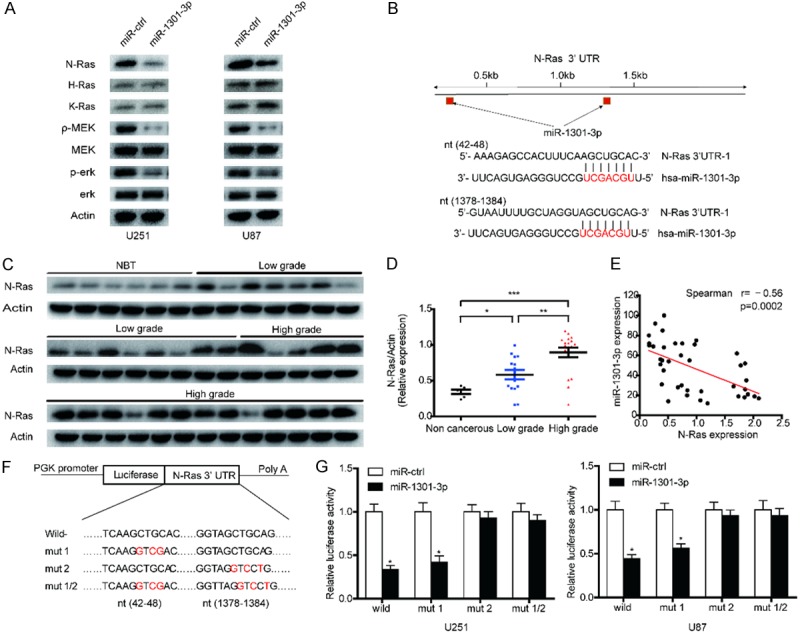

N-Ras is a direct target of miR-1301-3p in glioma cells

Activation of the Ras pathway has been well documented in various tumor types and ERK1/2 are major downstream effectors of Ras signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival. MiR-1301-3p can affect the proliferation of glioma cells, but does it affects the proliferation of glioma cells through the Ras pathway? Immunoblotting revealed that N-Ras, p-MEK and p-ERK expression levels were down-regulated in U87 and U251 cells by overexpression of miR-1301-3p (Figure 3A). Therefore, we believe that miR-1301-3p can indeed affect the Ras pathway. MiRNAs repress transcription or induce mRNA degradation by binding to complementary sequences in the 3’-UTRs of their target mRNA molecules. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis that miR-1301-3p can affect the Ras pathway by targeting a gene in it. To identify the mechanism of the oncogenic effects of miR-1301-3p in glioma cells, we used the bioinformatic tools, miRNAWalk 2.0 and TargetScan, to identify potential targets of miR-1301-3p. There were 2013 genes overlapping between the target genes predicted by these two programs (not show). Here, we mainly focused on genes involved in the Ras pathway (Figure 3B). To further determine the correlation between miR-1301-3p and N-Ras levels, we measured the levels of N-Ras protein in glioma specimens and non-cancerous brain tissues. The results showed that the average expression levels of N-Ras were significantly higher in tumor tissues than in the non-cancerous brain tissues and its expression was positively correlated with the degree of glioma malignancy (Figure 3C and 3D). Then, we determined the correlation between N-Ras and miR-1301-3p expression levels in the same glioma tissues. As shown in Figure 3E, Spearman’s correlation analysis demonstrated that N-Ras levels in glioma samples were inversely correlated with miR-1301-3p expression levels (Spearman’s correlation r=-0.56). Thus, lower levels of miR-1301-3p in glioma are associated with induction of N-Ras, which may in turn induce tumorigenesis. We then performed luciferase reporter assays to determine whether miR-1301 could directly bind to the 3’-UTR of N-Ras. U251 and U87 cells were co-transfected with vectors harboring wild-type or mutant N-Ras 3’-UTRs (Figure 3F) and miR-1301-3p mimic. Luciferase activity in U251 cells was markedly decreased after transfection with wild-type vector and miR-1301-3p mimics (Figure 3G). Luciferase activity was also significantly decreased when the poorly conserved binding site 1 (7mer) was mutated, whereas mutation of conserved binding site 2 (7mer) nearly rescued the decrease. Similar results were obtained in U87 cells (Figure 3G). These data suggest that miR-1301-3p directly regulates N-Ras expression through its binding to site 2 (nt1378-1384) in the 3’-UTR of N-Ras.

Figure 3.

MiR-1301-3p directly targets N-Ras and suppresses the activity of the Ras-MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in GBM cells. A. N-Ras, H-Ras, K-Ras, MEK, p-MEK, ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 expression levels in indicated cells were determined by western blotting. B. Predicted miR-1301-3p binding sites in the 3’-UTR of the N-Ras gene. C, D. The expression levels of N-Ras in NBTS and glioma specimens were determined by western blotting; the fold changes were normalized to β-Actin. The non-neoplastic brain tissues (n=6) were collected from brain trauma surgery. The low-grade (n=15) represents samples derived from grades I and II glioma tissues, whereas high-grade (n=18) represents grades III and IV glioma tissues. Data represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. E. Pearson’s correlation analysis of the relative expression levels of miR-1301-3p and the relative protein levels of N-Ras. F. Wild-type and mutant N-Ras 3’-UTR reporter constructs. G. Luciferase reporter assays were performed in U251 and U87 cells with co-transfection of indicated wild-type or mutant 3’-UTR constructs and miR-1301-3p mimic. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Data shown are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05.

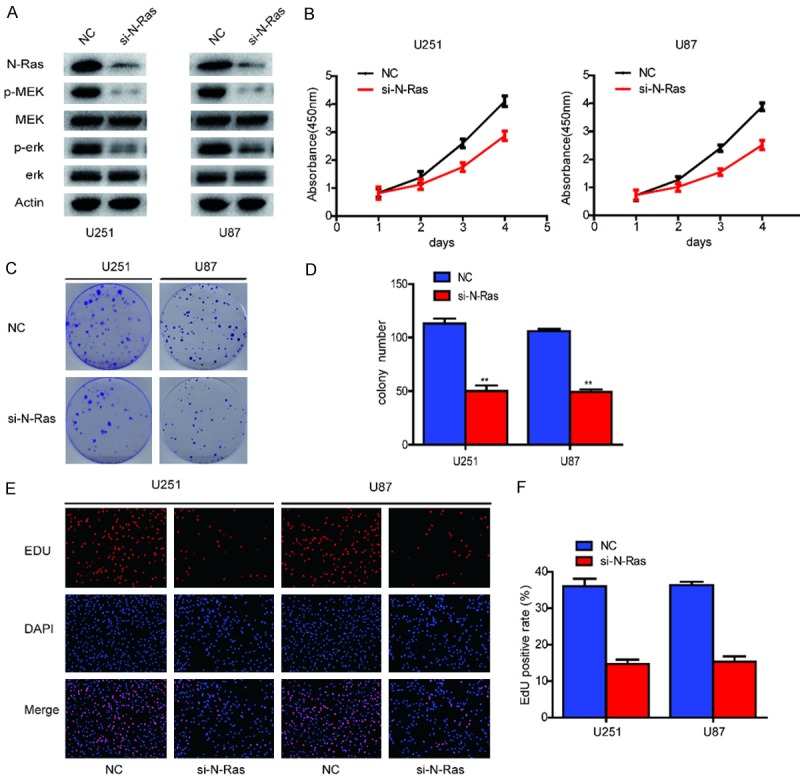

Down-regulation of N-Ras exhibited a similar effect to that of miR-1301-3p overexpression in glioma cells

Previous studies have suggested that N-Ras plays a critical role in the development and progression of various types of human cancers, including GBM. Analysis of N-Ras expression using the CGGA, TCGA, GSE4290 and GSE16011 databases revealed significant upregulation of N-Ras in all subtypes of GBM compared with NBTs (Supplementary Figure 1). Having verified that N-Ras is a direct target of miR-1301-3p in human gliomas, we wondered whether N-Ras is a downstream effecter of miR-1301-3p that mediates its function. To confirm this, we transfected siNC and siN-Ras into U87 and U251 cells to knock down the expression of N-Ras. Western blot analysis indicated that the N-Ras small interfering RNA could effectively suppress the expression of N-Ras protein. Moreover, the activity of the N-Ras pathway was inhibited (Figure 4A). The effects of N-Ras knockdown on cell viability and growth were evaluated in U87 and U251 cells using CCK-8, colony formation and EDU assays. We found that knockdown of N-Ras expression dramatically inhibited the proliferation of GBM cells (Figure 4B-F). These results were consistent with the effect of miR-1301-3p overexpression.

Figure 4.

Down-regulation of N-Ras inhibits glioma cell proliferation in vitro. A. Western blot analysis of N-Ras, MEK, p-MEK, ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 expression in U251 and U87 cells after knockdown of N-Ras. B. Proliferation ability was determined using the CCK-8 assay following culture for 96 h. Data are presented as the means of triplicate experiments. C, D. Long-term cell viability was evaluated using the colony formation assay. Data are presented as the means of triplicate experiments. E, F. Proliferating cells were examined using the EDU assay. Representative images are shown (original magnification, 200×). (**P<0.01).

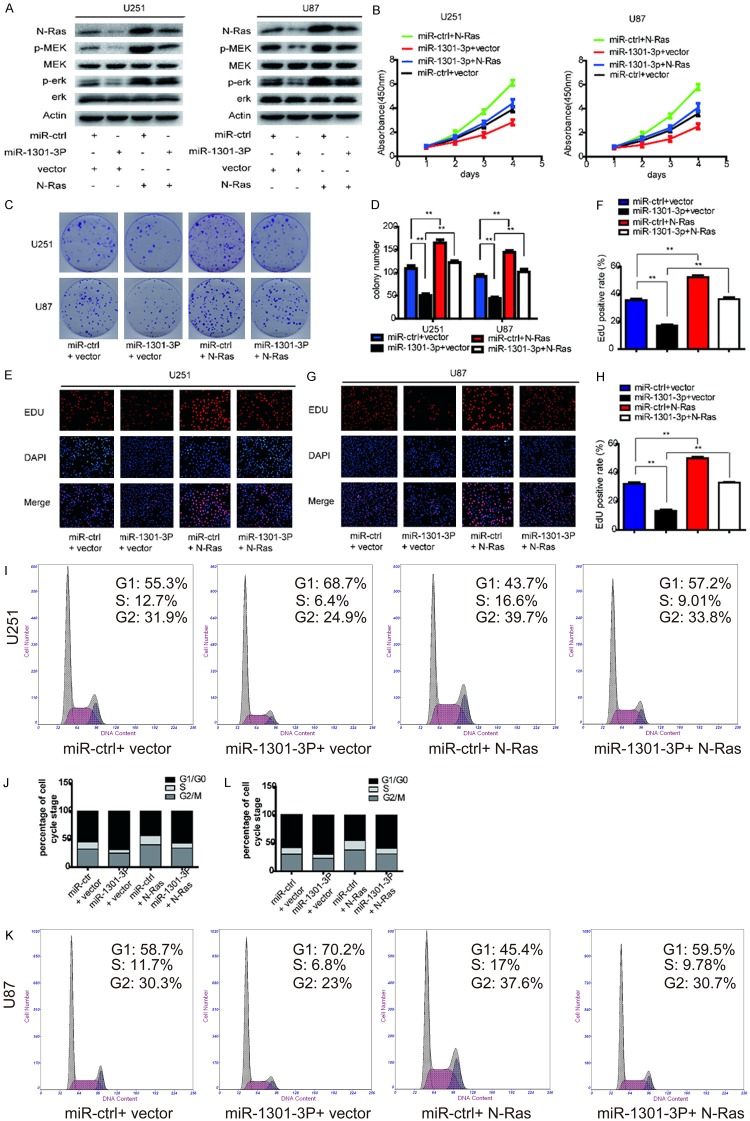

Reintroduction of N-Ras attenuates the effect of miR-1301-3p on the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma cells

As shown above, overexpression of miR-1301-3p inhibited the proliferation of glioma cells and N-Ras was validated as a direct target of miR-1301-3p. Therefore, we addressed whether changes in cell phenotypes after miR-1301-3p overexpression resulted directly from the down-regulation of N-Ras and its downstream pathways. PcDNA3-N-Ras plasmids were transfected into U87 and U251 cells stably expressing miR-1301-3p or miR-ctrl. As shown in Figure 5A, the decreased level of N-Ras due to miR-1301-3p overexpression was rescued by overexpression of N-Ras. Interestingly, the phosphorylation levels of MEK and ERK1/2 were altered in a similar way to the expression level of N-Ras; that is, decreased levels of p-MEK and p-ERK1/2 due to miR-1301-3p overexpression could be rescued by up-regulation of N-Ras (Figure 5A). To further confirm whether N-Ras is an important target of miR-1301-3p in cell proliferation, further experiments on the cell cycle and proliferation were conducted. As indicated in Figure 5B-L, the the cell cycle status and the inhibition of proliferation induced by miR-1301-3p were reversed by N-Ras overexpression. These results suggest that N-Ras is a functional target of miR-1301-3p in glioblastoma cells.

Figure 5.

N-Ras reintroduction reverses the inhibitory effect of miR-1301-3p. A. The rescue experiment was performed by introducing pcDNA3.1-N-Ras or pcDNA3.1 in the presence or absence of ectopic miR-1301-3p or miR-ctrl expression in U87 and U251 cells. Western blot analysis of N-Ras, MEK, p-MEK, ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 in the indicated cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. B-D. Cell viability of glioma cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-N-Ras and miR-1301-3p separately or together was detected using the CCK-8 and colony formation assays. E-H. Cell proliferative potential was evaluated using the EDU assay 48 h after co-transfection. I-L. Cell cycle distribution of glioma cells was measured using flow cytometry.

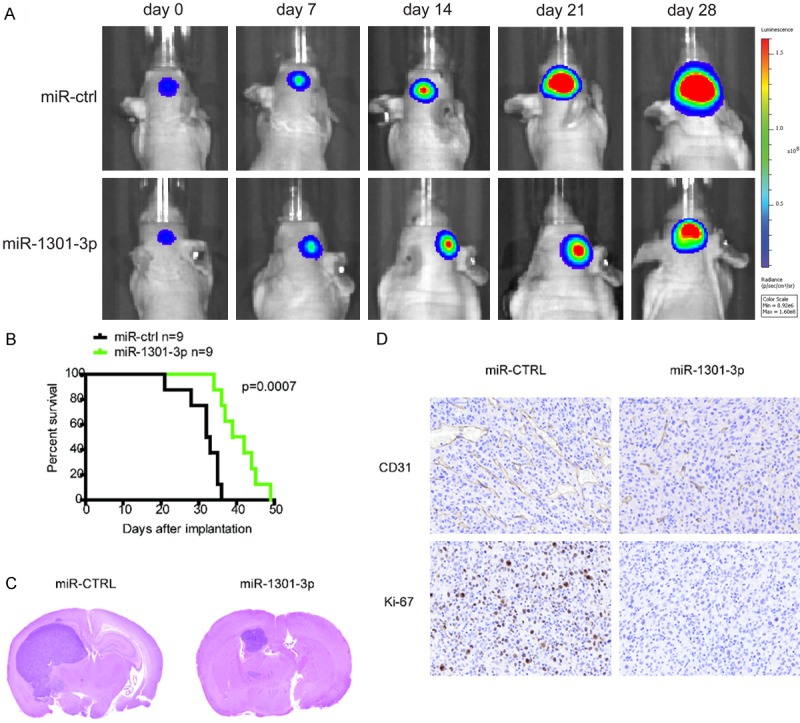

MiR-1301-3p suppresses glioblastoma xenograft growth in vivo

Considering the remarkable inhibitory effects of miR-1301-3p on glioblastoma in vitro, we extended our investigation to examine if miR-1301-3p could retard glioblastoma growth in vivo using nude mice. Before implantation, U87 glioblastoma cells were co-infected with lentivirus expressing luciferase with miR-ctrl or miR-1301-3p. The intracranial tumor volumes of the miR-1301-3p groups were significantly reduced compared with those of the miR-ctrl groups. On days 14, 21, and 28 after implantation, the growth of intracranial tumors was significantly inhibited in association with increased expression of miR-1301-3p (Figure 6A). To analyze the survival of the different treatment groups, we generated Kaplan-Meier survival curves and found that the survival of mice injected with miR-1301-3p expressing U87 cells was significantly prolonged (Figure 6B). Tumor volumes were significantly different between the two groups as revealed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 6C). Further, immunohistochemical experiments were carried out to examine the levels of Ki67 and CD31, which are often used to reflect tumor proliferation and angiogenesis. We found that levels of these two proteins were significantly reduced in the miR-1301-3P groups. In conclusion, these data supported the tumor-suppressive roles of miR-1301-3p in vivo.

Figure 6.

MiR-1301-3p suppresses tumor growth in an intracranial xenograft model. A. U87 cells pretreated with a miR-ctrl or miR-1301-3p lentivirus and a lentivirus containing luciferase were implanted in the brains of nude mice, and tumor formation was assessed by bioluminescence imaging. Bioluminescent images were measured at days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after implantation. B. Overall survival was determined by Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and a log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences. C. Tumor volume in the LV-miRNA-1301-3p group was significantly diminished based upon HE histology. D. After sacrifice, mouse brain tissues were harvested, embedded, and cut into paraffin sections for immunohistochemistry analysis. The expression of CD31 and Ki67 in the LV-miRNA-1301-3p group was significantly reduced.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that the abnormal expression of miR-1301 was closely related to oral squamous carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer and chronic myeloid leukemia [25,36-39]. However, its expression in glioma tissues was not clear. Through CGGA database analysis, we found that the expression of miR-1301-3p was decreased and negatively correlated with glioma grade. To verify the expression level of miR-1301-3p in glioma tissues, we randomly selected 33 different grades of glioma tissues and six cancerous brain tissues, and using independent qRT-PCR, we found that the expression of miR-1301-3p in glioma tissues was significantly lower than that in non-cancerous brain tissues. Moreover, our results showed that the expression of miR-1301-3p was significantly lower in high-grade gliomas than in low-grade gliomas, indicating that the expression level of miR-1301-3p was negatively correlated with glioma grade. Whether miR-1301-3p could be a biomarker of early stage diagnosis warrants further study.

Emerging evidence has shown that some miRNAs play significant roles in the development and progression of glioma. The abnormal expression of these miRNAs is closely related to malignant biological behaviors, including proliferation, invasion, apoptosis and angiogenesis. To study the effect of miR-1301-3p on the proliferation of glioma cells, we up-regulated miR-1301-3p in glioma cells by transfecting them with miR-1301-3p lentivirus. We obtained stably transfected glioma cells and CCK-8, colony formation and EDU assays showed that their proliferation capacity in both the short and long term was significantly decreased. Through flow cytometry assay, we found that miR-1301-3p could arrest cells at G1/S phase, which inhibits proliferation. As is well known, regulation of the cell cycle mainly depends on the protein kinase complex, which is composed of various cell cycle proteins (cyclins) and the corresponding cyclin dependent kinases (cyclin-dependent-kinase, CDK). Among them, CyclinE-CDK2 and CyclinE-CDC2, the two key kinase complexes, play vital roles in transition from the G1 phase to the S phase, enabling cells to initiate DNA synthesis by phosphorylation of a series of downstream substrates such as Rb, NPAT and P107 [40-42]. By western boltting, we found that the expression levels of CDK2, CDC2 and cyclinE1 were significantly decreased after overexpression of miR-1301-3p. Therefore, we suggest that miR-1301-3p can arrest the cell cycle in the G1 phase by inhibiting the expression of CDK2, CDC2 and cyclinE1.

The Ras family plays pivotal roles in the transduction of several growth and differentiation factor stimuli. The expression of N-Ras is closely related to the degree of the cancer malignancy, including for glioma, melanoma, breast cancer and other cancers [43-46]. Recent evidence has indicated that miRNAs can regulate the expression of Ras family proteins. For example, overexpression of miR-181a can led to reduced proliferation, impaired colony formation and increased sensitivity to chemotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells by targeting N-Ras and K-Ras [44,47]. In this study, we have demonstrated that the N-Ras oncogene is a target of miR-1301-3p in vitro and in vivo. Firstly, luciferase reporter assays confirmed that miR-1301-3p can specifically bind to the 3’-UTR region of the N-Ras transcript. Secondly, the expression of N-Ras was significantly decreased in glioma cells stably expressing miR-1301-3p. Thirdly, the expression of N-Ras protein was negatively correlated with miR-1301-3p in clinical specimens. Finally, inhibition of N-Ras expression by miR-1301-3p inhibits constitutive phosphorylation of MEK and ERK1/2 which are downstream proteins of the Ras/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. Taken together, our results provide the first evidence that miR-1301-3p is significant in suppressing glioma cell growth through inhibition of N-Ras and its downstream Ras/MEK/ERK1/2 signaling pathway.

In summary, the present study provides novel evidence of an important link between miR-1301-3p and tumorigenesis in human glioma. Our findings suggest that miR-1301-3p functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating N-Ras expression. MiR-1301-3p impairs tumor growth through inhibiting Ras/MEK/ERK1/2 pathways at multiple levels. Although miRNA-based therapeutics are still in the initial stages of development, our findings are encouraging and suggest that miR-1301-3p has potential as a diagnostic/prognostic marker and novel therapeutic target for glioma. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to determine the exact mechanism of decreased miR-1301-3p expression during the progression of glioma and to further explore other possible targets of miR-1301-3p in glioma. Additionally, a large cohort study, incorporating N-Ras expression and function should also be investigated.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Research Special Fund For Public Welfare Industry of Health (201402008), the National Key Research and Development Plan (2016YFC0902500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672501, 81472362, 81302184), Jiangsu Province’s Natural Science Foundation (20131019, 20151585), the Program for Advanced Talents within Six Industries of Jiangsu Province (2015-WSN-036, 2016-WSW-013), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Epidemiology and etiology of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:93–108. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0991-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neuro-oncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.20069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagarajan RP, Costello JF. Epigenetic mechanisms in glioblastoma multiforme. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA Jr, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SK, Shinjo SM, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holland EC. Gliomagenesis: genetic alterations and mouse models. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:120–129. doi: 10.1038/35052535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louis DN. Molecular pathology of malignant gliomas. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:97–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. OncomirsmicroRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, Horvitz HR, Golub TR. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenouda SK, Alahari SK. MicroRNA function in cancer: oncogene or a tumor suppressor? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s10555-009-9188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munker R, Calin GA. MicroRNA profiling in cancer. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;121:141–158. doi: 10.1042/CS20110005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babashah S, Soleimani M. The oncogenic and tumour suppressive roles of microRNAs in cancer and apoptosis. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1127–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi L, Cheng Z, Zhang J, Li R, Zhao P, Fu Z, You Y. hsa-mir-181a and hsa-mir-181b function as tumor suppressors in human glioma cells. Brain Res. 2008;1236:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi L, Zhang J, Pan T, Zhou J, Gong W, Liu N, Fu Z, You Y. MiR-125b is critical for the suppression of human U251 glioma stem cell proliferation. Brain Res. 2010;1312:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi ZM, Wang XF, Qian X, Tao T, Wang L, Chen QD, Wang XR, Cao L, Wang YY, Zhang JX, Jiang T, Kang CS, Jiang BH, Liu N, You YP. MiRNA-181b suppresses IGF-1R and functions as a tumor suppressor gene in gliomas. RNA. 2013;19:552–560. doi: 10.1261/rna.035972.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sana J, Hajduch M, Michalek J, Vyzula R, Slaby O. MicroRNAs and glioblastoma: roles in core signalling pathways and potential clinical implications. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1636–1644. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyner JW, Erickson H, Deininger MW, Willis SG, Eide CA, Levine RL, Heinrich MC, Gattermann N, Gilliland DG, Druker BJ, Loriaux MM. High-throughput sequencing screen reveals novel, transforming RAS mutations in myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2009;113:1749–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornblau SM, Womble M, Qiu YH, Jackson CE, Chen W, Konopleva M, Estey EH, Andreeff M. Simultaneous activation of multiple signal transduction pathways confers poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2358–2365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Min YH, Cheong JW, Kim JY, Eom JI, Lee ST, Hahn JS, Ko YW, Lee MH. Cytoplasmic mislocalization of p27Kip1 protein is associated with constitutive phosphorylation of Akt or protein kinase B and poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5225–5231. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang WC, Wang Y, Xiao LJ, Wang YB, Fu WM, Wang WM, Jiang HQ, Qi W, Wan DC, Zhang JF, Waye MM. Identification of miRNAs that specifically target tumor suppressive KLF6-FL rather than oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform. RNA Biol. 2014;11:845–854. doi: 10.4161/rna.29356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsurushima H, Tsuboi K, Yoshii Y, Ohno T, Meguro K, Nose T. Expression of N-ras gene in gliomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1996;36:704–708. doi: 10.2176/nmc.36.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birkenkamp KU, Geugien M, Schepers H, Westra J, Lemmink HH, Vellenga E. Constitutive NF-kappaB DNA-binding activity in AML is frequently mediated by a Ras/PI3-K/PKB-dependent pathway. Leukemia. 2004;18:103–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole AL, Subbanagounder G, Mukhopadhyay S, Berliner JA, Vora DK. Oxidized phospholipid-induced endothelial cell/monocyte interaction is mediated by a cAMP-dependent R-Ras/PI3-kinase pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1384–1390. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000081215.45714.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santarpia L, Myers JN, Sherman SI, Trimarchi F, Clayman GL, El-Naggar AK. Genetic alterations in the RAS/RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways in the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:2974–2983. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posch C, Moslehi H, Feeney L, Green GA, Ebaee A, Feichtenschlager V, Chong K, Peng L, Dimon MT, Phillips T, Daud AI, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE, Ortiz-Urda S. Combined targeting of MEK and PI3K/mTOR effector pathways is necessary to effectively inhibit NRAS mutant melanoma in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4015–4020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216013110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, Barbisin M, Xu NL, Mahuvakar VR, Andersen MR, Lao KQ, Livak KJ, Guegler KJ. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X. A PCR-based platform for microRNA expression profiling studies. RNA. 2009;15:716–723. doi: 10.1261/rna.1460509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian X, Yu J, Yin Y, He J, Wang L, Li Q, Zhang LQ, Li CY, Shi ZM, Xu Q, Li W, Lai LH, Liu LZ, Jiang BH. MicroRNA-143 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis and sensitizes chemosensitivity to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancers. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1385–1394. doi: 10.4161/cc.24477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Z, Chen Q, Li C, Wang L, Qian X, Jiang C, Liu X, Wang X, Li H, Kang C, Jiang T, Liu LZ, You Y, Liu N, Jiang BH. MiR-124 governs glioma growth and angiogenesis and enhances chemosensitivity by targeting R-Ras and N-Ras. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:1341–1353. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YY, Sun G, Luo H, Wang XF, Lan FM, Yue X, Fu LS, Pu PY, Kang CS, Liu N, You YP. MiR-21 modulates hTERT through a STAT3-dependent manner on glioblastoma cell growth. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:722–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rentoft M, Fahlen J, Coates PJ, Laurell G, Sjostrom B, Ryden P, Nylander K. miRNA analysis of formalin-fixed squamous cell carcinomas of the tongue is affected by age of the samples. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Han W, Ma Y, Cui L, Tian Y, Zhou Z, Wang H. P53-dependent miRNAs mediate nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in colonic carcinogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;85:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, He X, Liu Y, Ye Y, Zhang H, He P, Zhang Q, Dong L, Liu Y, Dong J. microRNA-320a inhibits tumor invasion by targeting neuropilin 1 and is associated with liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:685–694. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bi D, Ning H, Liu S, Que X, Ding K. miR-1301 promotes prostate cancer proliferation through directly targeting PPP2R2C. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;81:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nurse P, Thuriaux P. Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1980;96:627–637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaldis P, Aleem E. Cell cycle sibling rivalry: Cdc2 vs. Cdk2. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1491–1494. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng M, Tang H, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Xiong W, Zheng Y, Ye Q, Zeng X, Liao Q, Guo X, Li X, Ma J, Li G. miR-216b suppresses tumor growth and invasion by targeting KRAS in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2997–3005. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang X, Schwind S, Santhanam R, Eisfeld AK, Chiang CL, Lankenau M, Yu B, Hoellerbauer P, Jin Y, Tarighat SS, Khalife J, Walker A, Perrotti D, Bloomfield CD, Wang H, Lee RJ, Lee LJ, Marcucci G. Targeting the RAS/MAPK pathway with miR-181a in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59273–59286. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tilch E, Seidens T, Cocciardi S, Reid LE, Byrne D, Simpson PT, Vargas AC, Cummings MC, Fox SB, Lakhani SR, Chenevix Trench G. Mutations in EGFR, BRAF and RAS are rare in triple-negative and basal-like breast cancers from Caucasian women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcucci G, Radmacher MD, Maharry K, Mrozek K, Ruppert AS, Paschka P, Vukosavljevic T, Whitman SP, Baldus CD, Langer C, Liu CG, Carroll AJ, Powell BL, Garzon R, Croce CM, Kolitz JE, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD. MicroRNA expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1919–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.