Abstract

Background

We aimed to evaluate the potential benefits of the Leadership and Coaching for Health (LEACH) program on physical activity (PA), dietary habits, and distress management in cancer survivors.

Methods

We randomly assigned 248 cancer survivors with an allocation ratio of two-to-one to the LEACH program (LP) group, coached by long-term survivors, or the usual care (UC) group. At baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months, we used PA scores, the intake of vegetables and fruits (VF), and the Post Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) as primary outcomes and, for secondary outcomes, the Ten Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior adhered to and quality of life (QOL), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30).

Results

For primary outcomes, the two groups did not significantly differ in PA scores or VF intake but differed marginally in PTGI. For secondary outcomes, the LP group showed a significantly greater improvement in the HADS anxiety score, the social functioning score, and the appetite loss and financial difficulties scores of the EORTC QLQ-C30 scales from baseline to 3 months. From baseline to 12 months, the LP group showed a significantly greater decrease in the EORTC QLQ-C30 fatigue score and a significantly greater increase in the number of the Ten Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the LEACH program, coached by long-term survivors, can provide effective management of the QOL of cancer survivors but not of their PA or dietary habits.

Trial registration

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT01527409 (the date when the trial was registered: February 2012).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3290-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Health partnership, Health coaching, Balanced diet, Regular exercise, Positive thinking

Background

As a result of the substantial progress made in the early detection of cancer and new treatment technologies, the population of cancer survivors is increasing [1, 2]. Unfortunately, however, many cancer survivors develop poor health behaviors, such as physical inactivity, and exhibit overweight and psychological distress [3–5], and many develop recurrent or secondary primary cancers [6–9] during the transition from intensive treatment to survivorship.

Cancer can now be viewed as a chronic illness subject to management and long-term surveillance [10]. The US Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) new paradigm for the Chronic Care Model (CCM) of survivorship care planning (SCP) requires an ongoing collaborative partnership between patients and providers [10, 11]. These partnerships empower cancer patients by enabling them to manage their health crisis and quality of life (QOL) through self-management interventions [12, 13]. As in the proactive leadership trend in organizational management, self-leadership could empower patients to maintain healthy habits and grow positively in a CCM [3]. Since self-leadership, healthy behaviors, and post-traumatic growth factors are associated with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in cancer survivors [3], we are developing a novel health management program based on self-leadership that is designed to empower patients to proactively improve their health.

Another model for careful and proactive health management tailored to each patient’s health status and preference is health coaching, a hospital-based program that provides regular coaching sessions to patients by phone [14, 15]. The novel, trans-theoretical model (TTM)-based health management program we designed to empower cancer survivors to take care of themselves is called “Leadership and Coaching for Health” (LEACH).

Here we describe a 12-month randomized control trial that evaluated the benefits of LEACH on physical activity, dietary habits, and distress management compared with the benefits of routine care (standardized health education materials and a workshop) in a large sample of patients at 10 teaching hospitals, each with a different health partner and health master coach. Our hypothesis was that patients using LEACH would show increased physical activity, adopt a better diet, and attain greater positive growth than patients who received routine care.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy of a stage-tailored intervention based on the LEACH program from April 2012 through August 2013, using usual care as a control. The LEACH program consists of comprehensive, multifaceted core strategies from the TTM of health behavior change, the leadership model of “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” [16], and a Coaching Model [17]. The intervention includes 1) a TTM-based health education booklet and workbook for cancer survivors, 2) a workshop for empowerment of patients’ leadership skills, and 3) TTM-based telephone coaching with a health coaching manual (repeated assessment of stage of change, and planning how to achieve target health levels in accordance with their preferences and abilities) (Additional file 1: Table S1). The LEACH program covers physical activity, diet, and distress management.

Eligibility criteria

We used cancer registries from 10 South Korean teaching hospitals, each with a different health partner and health master coach. Cancer survivors who completed primary cancer treatment (in situ, localized, or regional with a favorable prognosis) within the last 24 months for breast, stomach, colon (other than rectal), and lung cancer within 18 months of completion of primary treatment were identified. To be included in the study, a patient had to 1) be ≥20 years old, 2) have a platelet count ≥100,000/mm3, 3) have a serum hemoglobin ≥10 g/dl, and 4) have not already met two or more behavioral goals aimed for in the study (i.e., i) energy expenditure achieved by at least moderate exercise for at least 150 min/week; ii) intake of ≥5 servings of fruit and vegetables per day; iii) a total score > 72 points in the Post Traumatic Growth Inventory). Patients were excluded from the study if they 1) were currently receiving cancer treatment, 2) had a progressive malignant disease or a recurrent, metastasized, or additional primary cancer, 3) had a condition that might compromise adherence to an unsupervised exercise program (e.g., uncontrolled congestive heart failure or angina, recent myocardial infarction, breathing difficulties requiring oxygen use or hospitalization, unable to walk without a walker or wheelchair, or were planning to receive hip or knee replacement surgery), 4) had a condition that could interfere with ingestion of a diet high in vegetables and fruit (e.g., kidney failure or need for chronic warfarin, 5) a serious psychological disorder (e.g., bipolar disease, schizophrenia, or an eating disorder), 6) had an infection (body temperature ≥ 37.2 °C or WBC ≥11,000 mm3), 7) had visual or motor dysfunction, or 8) were pregnant.

Participant recruitment

Permission to contact patients was obtained from the patients’ physician. Recruitment was either by a mailed letter of invitation or by direct approach by a research staff member in an outpatient department in a study hospital. The letters of invitation, which were stamped with an official approval seal from the Institutional Review Board, included an explanation of the LEACH study, a LEACH study promotional leaflet, a preaddressed, postage-paid return envelope, and a brief instrument that screened for ineligibility factors. After the prescreening, an oncologist and a research staff member in each study hospital confirmed that patients met the eligibility criteria by reviewing medical records and by blood tests. Research staff then related the details of the study to participants who met the eligibility criteria and who provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each hospital.

Random assignment

With the aid of a computerized random number generator (SAS 9.1.3, Proc plan), we randomly assigned eligible participants, two-to-one, to the intervention or the usual care group. To minimize the effects of potentially confounding variables on outcomes, we performed block randomization with 8 strata defined by type of cancer (breast, stomach, colon, or lung) and number of behavior goals practiced at the study entry (0 or 1 out of 3 defined possible behaviors).

Training programs for health master coach and health partner

For the LEACH study, we developed two training programs: the “Health Master Coach Program” for professionals and the “Health Partner Program” for long-term cancer survivors. “Health Partners” were trained by the “Health Partner Program” and are mentored and supervised by a Health Master Coach. Health Master Coaches were trained by the Health Master Coach Program, which consists of three components, such as education on health management in survivorship care planning (i.e., regular exercise, balanced diet, distress management, regular screening, no smoking and drinking, and management of chronic fatigue), leadership, coaching, and facilitator training. The education on the teaching and learning methods was a 72-h group session in parallel with actual practice. The health partners had been trained by the “Health Partner Program,” which is 3-month program consisting of health behavior management (8 h), leadership (16 h), and actual health coaching practice on prior learning via eight sessions using a multilateral telephone system (24 h).

Study conditions

Intervention (LEACH)

The LEACH program is based on 3 concepts—health education, leadership, and coaching, and it is managed through the interaction of a health master coach, health partners, and cancer patients. Health partners were long-term cancer survivors who formed partnerships with cancer patients and helped them achieve the target levels set for their health behaviors. Health master coaches were health professionals who mentored and supervised health partners.

First, patients were given a 1-h health education workshop (physical activity, dietary habits, and distress management) and a 3-h leadership workshop (Seven Habits of Highly Effective People with Cancer). Next, the Intervention group was also offered individual coaching by telephone for a 24-week period. A total of 16 sessions of tele-coaching were conducted: 30 min per week for 12 sessions, 30 min per 2 weeks for 2 sessions, and 30 min per month for 2 sessions were offered for the intervention group. Throughout the LEACH program, participants in the intervention group were provided individual coaching by telephone to practice patient health behaviors (such as regular exercise, balanced diet, and positive thinking) that have been reported to help in self-management. Based on the baseline health status assessment, health partners kept written records of their coaching, and master coaches gave feedback by reviewing those records. The principle investigator supervised these processes. The aim of the intervention was to achieve success in more than two health behaviors among three primary outcomes (physical activity ≧12.5 metabolic equivalents of task (METs) hours per week, daily intake of fruit and vegetables ≧5 dishes per day, and total PTGI ≧72). The secondary outcomes were to improve QOL and leadership of cancer survivors.

Intervention materials

Health education materials

Health education materials based on the TTM of health behavior change included information about 3 intervention areas—physical activity, dietary habits, and distress management. We made the material easy for health partners to understand so that they, in turn, could make it easy for patients to understand.

Health leadership-coaching workbook

Typically, patient health education does not involve interactions. We changed this by developing a leadership-coaching workbook that patients could work with to target their goal, set their action plan, and practice health leadership skills. The health education material in the workbook was based on a TTM model, self-leadership, and coaching strategy. The workbook was provided to health partners and patients.

Health coaching manual

Since health partners were not coaching professionals, we developed a coaching manual that they could use to guide patients on how to achieve the target levels for their health in accordance with their preferences and abilities using a TTM model, self-leadership, and coaching strategy.

Control material

The control group was encouraged to continue their usual care and was given a health education booklet on physical activity, dietary habits, and distress management that was not based on the core strategies from the TTM of health behavior change, as well as a 4-h health education lecture on physical activity, dietary habits, distress management, and screening for a 2nd cancer.

Quality assurance

Quality assurance covered study personnel, Health Partners [18], Health Master Coach training programs [18], experts’ supervision of the LEACH interventions, and the quality assurance committees. All research staff involved in screening and recruiting participants passed their local institution certification requirements for the ethical conduct of research (The Collaborative Institutional Training Initiatives).

Primary outcome

The patients were evaluated at 0, 3, 6, and 12 months. However, due to the lack of participants in the 6-month period, we did not include the 6-month follow-up results in the statistical analyses for this study. The primary outcomes were improvements in physical activity, diet, and post-traumatic growth. Physical activity was measured in METs (kcal/kg/week) using survey responses about the time, length, and intensity of physical activity [19] following the ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription [20]. Diet was evaluated with validated questions about daily intake of vegetables and fruits, and dietary pattern was checked with a questionnaire based on the “Rules for National Cancer Prevention: Dietary Practice Guideline,” which contains 10 questions exploring nutrition balance and dietary habits, such as eating speed and frequency [21, 22]. To evaluate diet, the survey questionnaire was modified based on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data [23]. Posttraumatic growth was measured with the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), a 21-item scale that assesses positive outcomes from persons who experienced traumatic events [24]. Each item was scaled on a 6-point Likert score from 0 to 5.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were improvement in leadership, HRQOL, satisfaction with life, depression and anxiety, distress in response to a specific traumatic event, perceived social support, and number of the Ten Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior adhered to. All of the secondary outcome questionnaires were validated in a Korean version with cancer survivors [3, 25, 26].

Cancer survivors’ leadership

We measured the 7 habits of highly effective people with cancer using the Seven Habit Profile (7HP) [16]. Each question was scored on a 6-point Likert scale, with the sum of the 3 questions covering one subscale, therefore, the total score of each domain was 18. The total of 27 questions consists of 9 subscales, higher scores representing the closer alignment with leadership criteria.

Health related quality of life

HRQOL was assessed using the 30-item European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) based on a 4-point Likert scale [26, 27]. Global life satisfaction was assessed using Diener’s Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), which is scored from 1 to 7 so that the possible range is from 5 to 35; higher scores indicate higher satisfaction [28]. Psychological distress was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [29]; total scores range from 0 to 21 for each of the anxiety and depression subscales. Self-reported current subjective cancer-induced distress in response to a specific traumatic event was rated using the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) [25]. The 22-item scale is composed of 3 subscales representative of the major symptom clusters of post-traumatic stress and this questionnaire is scored with 5-point Likert scales, which comprise 0 (not at all), 1 (a little bit), 2 (moderately), 3 (quite a bit), and 4 (extremely). Perceived social support was assessed using the 20-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) [30]. To obtain a score for overall support, the average of all 19 item scores are calculated and then can be transformed to a 0–100 scale; however, one item rates the number of close friends or relatives.

Patients were also asked to rate how they applied the following Ten Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior [3] (i.e., positive thinking, regular exercise, balanced diet, etc.) to improve QOL. Health behavior stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) were based on the TTM [31]. Behavior stages range from 1 (pre-contemplation) to 5 (maintenance stage) for each item [31].

Statistical approach

Anticipating a 20% dropout rate, we set the recruitment goal to 248 participants based upon the following assumptions: 1) a 2-sided Type I error of 0.05, 2) a 5% attainment of goal behavior in the usual care group (estimated Hawthorne effect), a 15–34% [32] attainment in the LEACH group, and a power of 78–89% to detect a between-arm difference. To achieve statistical power of 80% and an effect size of 0.3 by a two-sided t test, a 0.05 α level was used.

We explored intervention effects using an intent-to-treat analysis (ITT) that compared data from the original randomized groups regardless of group assignment. We used frequencies, means, SDs, and ranges to describe group characteristics, and the t-test (for continuous variables) and Chi-square test (for categorical variables) to evaluate homogeneity of the baseline characteristics between the two groups. We also analyzed each group’s success rate for combined primary outcomes. We calculated the rates of those who succeeded in performing more than two behaviors among three combined outcomes (physical activity ≧12.5 MET hours per week, daily intake of fruit and vegetables ≧5 dishes per day, and total PTGI ≧72) and compared these results between the UC and LP groups. Finally, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusting for baseline scores was conducted to compare between-group differences at each time point (3 and 12 months). The factors we explored were level of physical activity, body composition, diet quality, post-traumatic growth, self-leadership, satisfaction with life, HRQOL, anxiety and depression, and disease impact. For all statistical analyses, we included data for participants who completed the baseline questionnaire regardless of follow-up loss. All analyses were done with STATA version 13 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA) and SAS statistical package version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and all p values were two-sided.

Results

Participants

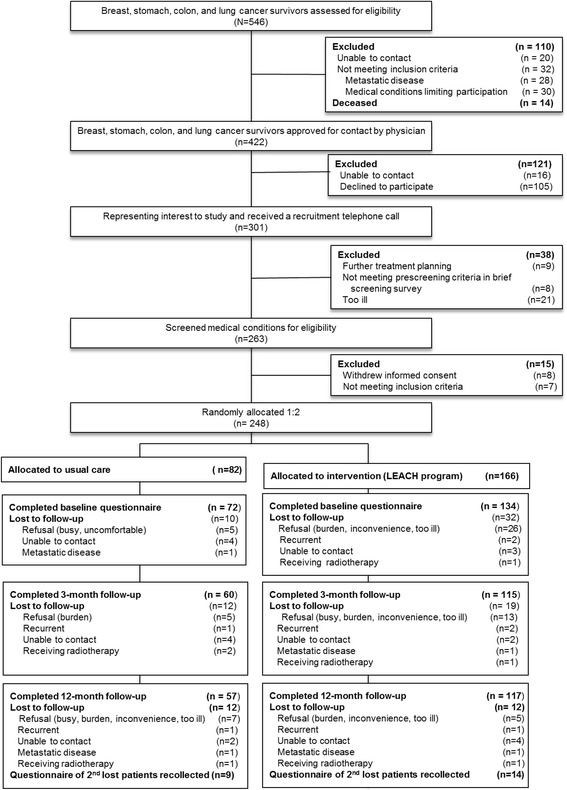

Of the 546 eligible patients, 298 were excluded for various reasons, leaving 248 (45.4%) for randomization into the study (Fig. 1). In the LP group, 115 (69.3%) participants completed the 12-month course at 3 months and 117 (70.5%) at 6–12 months. In the UC group, 60 (73.2%) participants completed the course at 3 months and 57 (71.3%) at 12 months.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participants: recruitment and eligibility screening, randomization, follow-up, and analyses

Baseline characteristics of participants

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of all participants. The scores of the two groups did not differ significantly for primary (PA, diet, and post-traumatic positive growth) or secondary (HADS, EORTC QLQ-C30, 7 Habit Profile, and MOS-SS) outcome measures (Table 1). The baseline questionnaire was completed by 72 (82.8%) participants in the UC group and 134 (80.72%) in the LP group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Control group | Intervention group | All participants | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 72) | (N = 134) | (N = 206) | ||

| No. Coaching attendees | 10.63 (6.29) | |||

| Age, years | 51.04 (7.55) | 50.52 (10.21) | 50.68 (9.43) | |

| Sex - no.(%) | ||||

| Male | 18 (25.00) | 24 (17.91) | 42 (20.39) | 0.229 |

| Female | 54 (75.00) | 110 (82.09) | 164 (79.61) | |

| Marital status- no.(%) (missing = 2) | ||||

| Married | 63 (87.50) | 106 (80.30) | 169 (82.84) | 0.193 |

| Widowed/Divorced/separated/single | 9 (12.50) | 26 (19.70) | 35 (17.16) | |

| Education - no.(%) (missing = 2) | ||||

| High-school graduate or less | 39 (54.17) | 66 (50.00) | 105 (51.47) | 0.569 |

| College graduate | 33 (45.83) | 66 (50.00) | 99 (48.53) | |

| Religion - no.(%) (missing = 4) | ||||

| No | 16 (22.86) | 47 (41.17) | 64 (31.19) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 54 (77.14) | 85 (64.39) | 139 (68.81) | |

| Household income –no.(%) (missing = 4) | ||||

| < 300million won | 25 (34.72) | 49 (37.69) | 49 (47.62) | 0.675 |

| ≥ 300million won | 47 (65.28) | 81 (82.38) | 128 (63.37) | |

| Cancer stage (missing = 7) | ||||

| 0 | 2 (2.94) | 3 (2.29) | 5 (2.51) | 0.476 |

| I | 31 (45.59) | 69 (52.67) | 100 (52.67) | |

| II | 28 (41.19) | 38 (29.01) | 66 (33.17) | |

| III | 4 (5.88) | 16 (12.21) | 20 (10.05) | |

| IV | 1 (1.47) | 1 (0.76) | 2 (1.01) | |

| Other (5,6) | 2 (2.94) | 4 (3.05) | 6 (3.02) | |

| Type of cancer | ||||

| Stomach | 17 (23.94) | 34 (25.76) | 51 (25.12) | |

| Lung | 3 (2.80) | 5 (5.20) | 5 (3.79) | |

| Breast | 42 (59.15) | 81 (79,98) | 123 (60.59) | |

| Colorectal | 5 (7.04) | 6 (4.55) | 11 (5.42) | |

| Gynecologic | 4 (5.63) | 5 (3.79) | 9 (4.43) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0.76) | 1 (0.49) | |

| Type of treatment (missing = 10) | ||||

| Surgery | 68 (98.55) | 127 (100.00) | 195 (99.49) | 0.174 |

| Radiotherapy | 39 (56.52) | 61 (64.80) | 100 (51.02) | 0.256 |

| Chemotherapy | 43 (62.32) | 76 (59.84) | 119 (60.71) | 0.735 |

| Hormonal therapy | 20 (50.0) | 31 (40.26) | 51 (43.59) | 0.314 |

| Weight, kg (missing = 1) | 56.31 (8.36) | 57.53 (8.72) | 57.10 (8.59) | 0.330 |

| BMI (missing = 1) | 21.70 (2.67) | 22.23 (3.00) | 22.05 (2.89) | 0.213 |

| Hemoglobin (missing = 14) | 13.05 (1.25) | 13.06 (1.22) | 13.05 (1.23) | 0.955 |

| Total Cholesterol-mg/dl (missing = 21) | 173.72 (28.62) | 181.9 (34.60) | 178.96 (11.44) | 0.103 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (missing = 87) | 116.33–72.94 | 112.9–72.93 | 117.52–72.94 | 0.462/0.999 |

| Baseline | ||||

| Vegetable intake 5 plates/day, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 22 (30.56) | 45 (33.58) | 67 (32.52) | 0.659 |

| No | 50 (69.44) | 89 (66.42) | 139 (67.48) | |

| Total-MET | 27.53 (19.82) | 26.67 (27.50) | 26.97 (25.04) | 0.799 |

| Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | ||||

| Relating to others | 20.83 (6.17) | 21.40 (6.64) | 21.21 6.47) | 0.568 |

| New possibilities | 14.36 (5.10) | 14.61 (4.70) | 14.52 (4.83) | 0.723 |

| Personal strength | 11.28 (4.37) | 11.90 (4.01) | 11.68 (4.14) | 0.308 |

| Spiritual change | 5.07 (3.09) | 4.72 (4.20) | 4.84 (3.08) | 0.444 |

| Appreciation for life | 10.21 (3.18) | 10.46 (2.92) | 10.37 (3.01) | 0.576 |

| Total | 61.78 (18.91) | 63.09 (18.51) | 62.63 (18.61) | 0.631 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values = mean (SD)

MET metabolic equivalent task, BMI body mass index

Effect of health partnership program

Table 2 shows each LP and UP group’s change of success rates in more than 2 of 3 primary outcomes (physical activity, dietary habits, and post-traumatic positive growth) from baseline to 3 and 12 months. The Chi-square test for each time point shows that the two groups did not differ significantly, however, in two or more health behavior goals. Table 3 shows the changes from baseline to 3 and 12 months in the two groups for all measures. For primary outcome scores, the two groups did not significantly differ in intake of vegetables and fruit (servings/day) (p = 0.819 for 3 months, and p = 0.413 for 12 months) and MET/h/day (p = 0.54 for 3 months, and p = 0.975 for 12 months), but differed marginally at 12 months in post-traumatic positive growth (p = 0.065). For secondary outcomes, the LP group showed a significantly greater decrease in the HADS anxiety score (p = 0.025), a significantly greater increase in the social functioning score of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (p = 0.018), and a significantly greater decrease in the appetite loss (p = 0.048) and financial difficulties scores (p = 0.036) of the EORTC QLQ-C30 from baseline to 3 months. From baseline to 12 months, the LP group, relative to the UC group, showed a significantly greater decrease in the EORTC QLQ-C30 fatigue score (p = 0.065) and a significantly greater increase in number of 10 Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior adhered to (p = 0.015). Differences in IES-R score between the UC and LP groups were marginally significant from baseline to 12 months (p = 0.068).

Table 2.

Primary outcomes over time

| Time point | Intervention group | Control group | P-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. | Success no. (%) | Total no. | Success no. (%) | ||

| Baseline | 134 | 47 (35.1) | 72 | 25 (34.7) | 0.960 |

| 3 months | 100 | 44 (44.0) | 55 | 20 (36.4) | 0.356 |

| 12 months | 92 | 42 (45.7) | 50 | 16 (32.0) | 0.114 |

Each time point includes three primary outcomes (MET, PTGI, Vegetable intake 5 plates/day), with two or more defining success

†Chi-square test

Table 3.

Effect of health partnership program

| Unadjusted estimates, mean (SD) | Adjusted analysis for intervention vs usual carea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | Intervention group | Control group | P value1) | ||

| MET/h/day | Baseline | 26.7 (27.5) | 27.5 (19.8) | |||

| 3 months | 27.1 (25.4) | 24.3 (24.6) | 26.2 (2.2) | 23.9 (3.0) | 0.540 | |

| 12 months | 23.5 (23.6) | 22.9 (24.6) | 22.9 (2.3) | 22.8 (3.3) | 0.975 | |

| PTGI-Total | Baseline | 63.1 (18.5) | 61.8 (18.9) | |||

| 3 months | 63.6 (19.3) | 61.2 (18.6) | 62.7 (1.3) | 62.1 (1.7) | 0.791 | |

| 12 months | 66.6 (19.3) | 60.2 (19.1) | 66.3 (1.6) | 61.2 (2.2) | 0.065* | |

| Vegetable intake n(%), ≥5 serves/day | Baseline | 45 (33.6) | 22 (30.6) | |||

| 3 months | 52 (42.6) | 27 (40.9) | 33.6 (4.9) | 31.0 (6.3) | 0.819 | |

| 12 months | 41 (36.9) | 26 (42.6) | 31.0 (5.4) | 37.3 (6.7) | 0.413 | |

| Leadership | Baseline | 121.3 (21.2) | 120.1 (20.8) | |||

| 3 months | 125.0 (21.7) | 121.6 (20.2) | 123.1 (1.3) | 121.8 (1.9) | 0.552 | |

| 12 months | 127.7 (22.1) | 122.8 (20.6) | 125.4 (1.6) | 123.3 (2.2) | 0.433 | |

| HADS | ||||||

| Anxiety | Baseline | 5.7 (3.4) | 5.9 (3.1) | |||

| 3 months | 5.0 (3.0) | 6.1 (3.1) | 5.2 (0.2) | 6.0 (0.3) | 0.025** | |

| 12 months | 5.1 (3.0) | 5.8 (2.9) | 5.2 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) | 0.228 | |

| Depression | Baseline | 6.4 (3.5) | 6.1 (3.1) | |||

| 3 months | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.3) | 0.986 | |

| 12 months | 5.4 (3.4) | 5.6 (3.1) | 5.3 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) | 0.428 | |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | ||||||

| Functional scales | ||||||

| Global health status | Baseline | 64.5 (19.9) | 63.4 (18.7) | |||

| 3 months | 67.7 (18.7) | 65.7 (17.5) | 67.0 (1.6) | 66.0 (2.3) | 0.705 | |

| 12 months | 70.1 (17.1) | 65.3 (17.9) | 69.0 (1.6) | 66.0 (2.2) | 0.269 | |

| Physical functioning | Baseline | 78.6 (13.5) | 77.9 (11.1) | |||

| 3 months | 80.0 (12.1) | 78.4 (12.0) | 79.4 (0.9) | 79.3 (1.3) | 0.942 | |

| 12 months | 82.9 (13.1) | 78.2 (12.4) | 81.9 (1.2) | 78.7 (1.6) | 0.123 | |

| Role functioning | Baseline | 79.4 (21.4) | 77.9 (19.8) | |||

| 3 months | 80.9 (18.1) | 77.3 (18.4) | 80.3 (1.5) | 78.5 (2.2) | 0.497 | |

| 12 months | 82.7 (19.8) | 79.9 (18.9) | 80.9 (1.8) | 81.1 (2.4) | 0.958 | |

| Emotional functioning | Baseline | 76.8 (19.4) | 73.0 (23.0) | |||

| 3 months | 78.0 (19.1) | 74.5 (16.5) | 76.7 (1.5) | 75.3 (2.2) | 0.602 | |

| 12 months | 78.0 (19.9) | 75.9 (18.3) | 76.2 (1.9) | 77.7 (2.4) | 0.625 | |

| Cognitive functioning | Baseline | 76.7 (19.9) | 72.6 (20.9) | |||

| 3 months | 80.1 (17.2) | 72.5 (20.2) | 77.6 (1.4) | 75.1 (2.4) | 0.322 | |

| 12 months | 78.1 (14.9) | 76.5 (19.2) | 76.8 (1.6) | 78.4 (2.1) | 0.552 | |

| Social functioning | Baseline | 75.8 (26.8) | 73.1 (23.4) | |||

| 3 months | 85.4 (19.3) | 76.3 (20.2) | 84.8 (1.8) | 77.4 (2.5) | 0.018 | |

| 12 months | 85.3 (19.5) | 78.2 (22.4) | 84.8 (2.2) | 79.0 (2.9) | 0.123 | |

| Symptom scales | ||||||

| Fatigue | Baseline | 38.6 (20.9) | 40.8 (21.6) | |||

| 3 months | 33.5 (17.8) | 38.1 (17.7) | 34.3 (1.5) | 37.6 (2.2) | 0.214 | |

| 12 months | 33.8 (16.1) | 42.4 (21.4) | 34.8 (1.6) | 41.9 (2.1) | 0.010** | |

| Nausea/vomiting | Baseline | 4.6 (10.0) | 4.2 (10.6) | |||

| 3 months | 5.7 (10.6) | 5.3 (9.8) | 5.6 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.3) | 0.733 | |

| 12 months | 6.4 (14.5) | 7.8 (15.3) | 6.5 (1.6) | 7.7 (2.1) | 0.660 | |

| Pain | Baseline | 15.4 (19.2) | 21.4 (19.0) | |||

| 3 months | 11.9 (16.0) | 19.6 (19.6) | 13.6 (1.5) | 17.4 (2.1) | 0.146 | |

| 12 months | 13.1 (17.6) | 19.7 (21.4) | 15.5 (1.8) | 16.2 (2.3) | 0.810 | |

| Dyspnea | Baseline | 11.9 (19.9) | 19.4 (21.0) | |||

| 3 months | 8.2 (15.9) | 13.7 (16.6) | 10.3 (1.3) | 11.3 (1.9) | 0.668 | |

| 12 months | 10.6 (19.5) | 13.6 (17.9) | 12.1 (2.0) | 11.3 (2.6) | 0.797 | |

| Insomnia | Baseline | 28.8 (30.0) | 30.3 (28.9) | |||

| 3 months | 24.1 (24.50 | 26.7 (26.9) | 25.0 (2.1) | 25.7 (3.1) | 0.850 | |

| 12 months | 26.2 (27.9) | 32.0 (27.2) | 27.6 (2.5) | 29.1 (3.4) | 0.732 | |

| Appetite loss | Baseline | 12.8 (20.9) | 15.4 (24.8) | |||

| 3 months | 10.7 (17.6) | 17.3 (23.6) | 11.3 (1.8) | 17.7 (2.6) | 0.048 | |

| 12 months | 11.6 (17.6) | 13.6 (20.3) | 12.1 (2.0) | 13.7 (2.6) | 0.631 | |

| Constipation | Baseline | 16.9 (26.7) | 18.9 (24.1) | |||

| 3 months | 14.7 (23.3) | 16.3 (21.6) | 16.5 (1.8) | 16.0 (2.7) | 0.882 | |

| 12 months | 12.6 (18.1) | 17.7 (20.5) | 19.5 (2.2) | 16.5 (2.9) | 0.414 | |

| Diarrhea | Baseline | 13.8 (20.7) | 11.4 (18.8) | |||

| 3 months | 12.6 (18.1) | 14.0 (17.9) | 19.8 (4.1) | 10.0 (5.4) | 0.151 | |

| 12 months | 20.5 (45.6) | 9.5 (20.4) | 11.9 (1.5) | 15.3 (2.2) | 0.211 | |

| Financial Difficulties | Baseline | 20.3 (28.6) | 23.4 (26.0) | |||

| 3 months | 15.5 (25.5) | 26.8 (37.1) | 17.4 (2.6) | 27.0 (3.7) | 0.036 ** | |

| 12 months | 18.9 (26.6) | 20.4 (27.9) | 18.9 (2.5) | 19.3 (3.3) | 0.920 | |

| The MOS-SSS | Baseline | 65.6 (20.9) | 65.6 (20.6) | |||

| 3 months | 66.3 (21.1) | 67.9 (19.3) | 66.9 (1.4) | 65.7 (2.0) | 0.621 | |

| 12 months | 66.6 (21.1) | 68.0 (19.7) | 67.1 (1.7) | 65.3 (2.4) | 0.535 | |

| Health Behavior | Baseline | 4.9 (3.1) | 5.2 (2.7) | |||

| 3 months | 6.4 (2.7) | 5.5 (3.0) | 6.9 (0.3) | 6.2 (0.4) | 0.147 | |

| 12 months | 7.0 (2.8) | 6.3 (2.7) | 6.3 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.3) | 0.015** | |

| IES-R | Baseline | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | |||

| 3 months | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | 0.759 | |

| 12 months | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | 0.068 * | |

aAdjusted baseline value with a statistical power of 80% and an effect size of 0.3 by a two-sided t test at the 0.05 α level was used

*p < 0.10 with bold

**p < 0.05 with bold

1)ANCOVA

MET Metabolic Equivalent Task, PTGI Post-traumatic Growth Inventory, HADS Hospital and Anxiety Scale, EROTC QLQ-C30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30, MOS-SSS Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, IES-R Impact of Event Scale--Revised

Otherwise, other secondary outcomes such as depression (p = 0.9.86 for 3 months, and p = 0.428 for 12 months), QOL functioning (i.e., physical function, role function, emotional function, and cognitive function) and several symptom scales did not show statistically significant changes.

Discussion

Despite the fact that cancer survivors are in a “teachable moment” at a time when they are highly motivated to change behaviors so as to improve their health [33], many practice poor health behaviors [34–37]. Therefore, in this program, we primarily targeted 3 intervention areas—physical activity, dietary habits, and post-traumatic positive growth—as well as secondary outcomes for health related quality of life and leadership improvement through health coaching. To our knowledge, this is the first health coaching program provided by long-term cancer survivors.

In this randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Health Partnership program, the health partners’ tele-coaching significantly improved several areas of HRQOL but failed to change primary health behavior outcomes compared with routine care. There were no significant improvements for the 3 primary targeted intervention areas such as physical activity, dietary habits, and post-traumatic positive growth. The effect was evident in several sub-scales of three well-validated HRQOL assessment measures (EORTC QLQ-C30, HADS, and IES-R) as secondary outcomes. The observed benefits showed clinically significant improvements in fatigue, social functioning, anorexia, financial difficulties (EORTC QLQ-C30), anxiety (HADS), IES-R score, and health behavior activation numbers among long-term cancer survivors.

Although limited evidence has suggested that behavioral interventions for cancer survivors based on the TTM and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can improve health outcomes, doubts remain about behavioral interventions to improve multiple behaviors simultaneously along with long-term health outcomes [38]. In RCTs based on TTM and CBT, our research team has showed that target goals could be improved by simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention [39], Health Navigation for cancer-related fatigue [40], and decision aids to help family caregivers discuss terminal disease status [41].

There are several possible explanations for our study findings. First, this study did not support our hypothesis that patients in the LEACH group would attain greater physical activity, intake of vegetables and fruit (servings/day), and post-traumatic positive growth than patients in the routine care group. In contrast to earlier RCTs of behavioral interventions for cancer survivors based on TTM, CBT, and health coaching, the LEACH program showed improvement only in secondary outcomes, such as anxiety, social functioning, anorexia, fatigue, financial difficulties, and the number of 10 Rules for Highly Effective Health Behavior adhered to [13, 42, 43].

We are particularly discouraged by the observation that the intervention and control groups did not differ in primary outcomes during the 12-month follow-up period. This may have been due to lower intervention intensity or low quality of coaching in the intervention arm. Our health coaching program intervention by long-term cancer survivors trained by the Health Partner Program may have important methodological limitations, including inadequate training of the health coach. We have tried to develop this program to provide a new paradigm of partnership between long-term cancer survivors and medical professionals to enable patients to manage their health crises and HRQOL across the cancer-care continuum. Specifically, our new model would enable long-term survivors to form partnerships between patients and physicians to make full use of their experience and wisdom gained during the “War with Cancer”; however, this study did not provide evidence of the effectiveness of the LEACH program.

Nonetheless, this study showed that Health Partner coaching was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in participants’ anxiety, and several aspects of HRQOL and health behavior practice during 3 or 12 months [13, 42, 43]. This fact means long-term cancer survivors can benefit from the Health Partner Program [44] at least in relation to distress and HRQOL management within the cancer care continuum. Therefore, these findings leave room for the possibility of improvement of the program and should not discourage development of new programs that allow long-term cancer survivors to be partners with health professionals in the cancer control continuum. Many trials may be needed to learn how to train survivors to be effective health coaches.

Our study has several limitations. First, the completion rate was low (30.7% of the patients did not complete the full 12-month telephone coaching) and this might have negatively influenced primary outcomes [45]. In addition, due to the lack of participants in the 6-month period, we did not include the 6 month follow-up results in the statistical analyses. Second, the participants did not represent the whole cancer population; most of the recruited participants were early-stage (in situ, localized, or regional cancers with a favorable prognosis) cancer survivors and this often leads to “ceiling effects” in which these participants often report little improvement relative to high baselines in a wide range of modifiable health behaviors and QOL items. Third, our measures of diet and PA were based on self-reports and might have therefore included reporting errors. Finally, our participants included a wide range of cancer types, which might have complicated the interpretation of our findings. If our study were done for a single type of cancer, the interpretation of the findings may have been easier. Further studies are needed to develop new creative programs that are more effective.

Conclusions

Although this program did not change the participants’ primary behaviors such as physical activity or dietary habits, the program was effective in improving cancer patients’ ability to manage their anxiety, social functioning, and symptoms. This health coaching program provides a creative partnership between long term cancer survivors and medical professionals enable cancer patients to manage their distress and QOL with positive growth.

Acknowledgement

We also thank for Miriam Bloom from Sci Writers and Editage who provided language edition.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center (1010470) in design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1320330) in the writing of the manuscript, in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and by the R&D Program for National Research Foundation of Korea (20100028631) in the interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

Identifying/confidential patient data should not be shared.

Authors’ contributions

YH participated in the design of the study, provided financial supports and study materials, collected and assembly the data, interpret the analyses and also participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. YA participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. MK participated in the design of the study, collected and assembly the data, interpret the analyses. JA participated in its design and coordination, collected study materials, conducted data analyses and also participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. BH participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SH Kim participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. ES participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. DY participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. JY participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. S Kim participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. SY participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. CH participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. KH Jung participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. MS participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. SN participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. KH Park participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. SH Park participated in the design of the study, provided study materials and patients, collected and assembly the data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at all participating institutions (Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, National Cancer Center, Samsung Medical Center, Korea University, Ajou University, Keimyung University Dong-san Hospital, Ajou University Hospital, Ewha Womans University Hospital) approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent.

All participants from each of the Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, National Cancer Center, Samsung Medical Center, Korea University, Ajou University, Keimyung University Dong-san Hospital, Ajou University Hospital, Ewha Womans University Hospital provided written informed consent.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CBT

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HRQOL

Health Related Quality of life

- IES-R

Impact of Events Scale-Revised

- LEACH

Leadership and Coaching for Health

- PA

Physical activity

- TTM

Trans-theoretical model

Additional file

The intervention included 1) a TTM-based health education booklet and work book for cancer survivors, 2) a workshop for empowerment of patients’ leadership skills, and 3) TTM-based telephone coaching with a health coaching manual (repeated assessment of stage of change, and planning how to achieve the health target levels in accordance with their preferences and abilities) are described in the Additional file 1: Table S1. (DOCX 22 kb)

Contributor Information

Young Ho Yun, Phone: +82-2-740-8417, Email: lawyun@snu.ac.kr, Email: lawyun08@gmail.com.

Young Ae Kim, Email: elkim7@gmail.com.

Myung Kyung Lee, Email: mlee005@gmail.com.

Jin Ah Sim, Email: jinah811@gmail.com.

Byung-Ho Nam, Email: byunghonam@ncc.re.kr.

Sohee Kim, Email: shkim@ncc.re.kr.

Eun Sook Lee, Email: eslee@ncc.re.kr.

Dong-Young Noh, Email: dynoh@snu.ac.kr.

Jae-Young Lim, Email: drlim1@snu.ac.kr.

Sung Kim, Email: sungkimm@skku.edu.

Si-Young Kim, Email: sykim55@chollian.net.

Chi-Heum Cho, Email: c0035@dsmc.or.kr.

Kyung Hae Jung, Email: khjung@amc.seoul.kr.

Mison Chun, Email: chunm@ajou.ac.kr.

Soon Nam Lee, Email: snlee@ewha.ac.kr.

Kyong Hwa Park, Email: khpark@korea.ac.kr.

Sohee Park, Email: soheepark@yuhs.ac.

References

- 1.Duk Hyoung Lee KP, Hyung Kook Y, Young Ae K, Eun Joo N. National Cancer Center: Ministry of Health and Welfare. 1st 2014. Cancer facts and figures 2014 in the Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yun YH, Sim JA, Jung JY, Noh DY, Lee ES, Kim YW, Oh JH, Ro JS, Park SY, Park SJ, et al. The association of self-leadership, health behaviors, and posttraumatic growth with health-related quality of life in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, Henrichs M, Carnicke CL. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249(6):751–757. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03330300035030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Sternfeld B, Madlensky L, Al-Delaimy WK, Thomson CA, Kealey S, Hajek R. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2345–2351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Kantsiper ME, Peairs KS, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, Wolff AC, Earle CC. Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: changes from 1998 to 2002. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1054–1061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, Grunfeld E, Muss HB, Vogel VG, Halberg F, Somerfield MR, Davidson NE. American Society of Clinical O: American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5091–5097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control. A national action plan for cancer survivorship: advancing public health strategies. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

- 10.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, Wagner EH. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(IOM) IoM . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams K, editor. Priority areas for National Action: transforming health care quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Synder DC, Morey MC, Sloane R, Stull V, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Pieper C, Hartman TJ, Miller PE, Mitchell DC, et al. Reach out to ENhancE wellness in older cancer survivors (RENEW): design, methods and recruitment challenges of a home-based exercise and diet intervention to improve physical function among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18(4):429–439. doi: 10.1002/pon.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charles P, Giraudeau B, Dechartres A, Baron G, Ravaud P. Reporting of sample size calculation in randomised controlled trials: review. BMJ. 2009;338:b1732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong B. How to calculate sample size in randomized controlled trial? J Thorac Dis. 2009;1(1):51–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covey SR. The Seven habits of highly effective people. 25. New York: US: Simon & Schuster; 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson FM. The handbook of coaching: a comprehensive resource guide for managers, executives, consultants, and human resource professionals. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun YH, Lee MK, Bae Y, Shon E-J, Shin B-R, Ko H, Lee ES, Noh D-Y, Lim J-Y, Kim S, et al. Efficacy of a training program for long-term disease-free cancer survivors as health partners: a randomized controlled trial in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7229–7235. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.12.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O Brien WL, Bassett DR, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9; SUPP/1):S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Sports M. Kenney WL, Humphrey RH, Bryant CX, Mahler DA. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim WY, Cho MS, Lee HS. Development and validation of mini dietary assessment index for Koreans. Korean Journal of Nutrition. 2003;36(1):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SY, Shin MH, Sung MK, Paik HY, Park YK, Kim J, Sohn JW, Kim WG, Jung HJ, Ahn YO. Establishment of Korean dietary guidelines for cancer prevention. Korean J Health Promot. 2011;11(3):129–143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the korea national health and nutrition examination survey (knhanes) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim HK, Woo JM, Kim TS, Kim TH, Choi KS, Chung SK, Chee IS, Lee KU, Paik KC, Seo HJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the impact of event scale-Revised. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang SM, Heo DS, Park SY, You CH, West K. Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(4):863–868. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021692.81214.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Dehaes JCJM, et al. The European-organization-for-research-and-treatment-of-cancer Qlq-C30 - a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical-trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer I. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zigmond ASSR. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The Transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)? Evidence for a "trial effect". J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00305-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demark-Wahnefried W, Pinto BM, Gritz ER. Promoting health and physical function among cancer survivors: potential for prevention and questions that remain. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5125–5131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Sternfeld B, Madlensky L, Al-Delaimy WK, Thomson CA, Kealey S, Hajek R, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2345–2351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol. 2011;28(3):753–765. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland JC. Managing depression in the patient with cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1987;37(6):366–371. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.37.6.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira MG, Figueiredo AP, Fincham FD. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and quality of life in colorectal cancer after different treatments: a study with Portuguese patients and their partners. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, Patrao TA, Baade PD, Lynch BM, Aitken JF, Meng X, Courneya KS. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2313–2321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SH, Shin MS, Lee HS, Lee ES, Ro JS, Kang HS, Kim SW, Lee WH, Kim HS, Kim CJ, et al. Randomized pilot test of a simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(2):E97–106. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E97-E106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun YH, Lee KS, Kim YW, Park SY, Lee ES, Noh DY, Kim S, Oh JH, Jung SY, Chung KW, et al. Web-based tailored education program for disease-free cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1296–1303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yun YH, Lee MK, Park S, Lee JL, Park J, Choi YS, Lim YK, Kim SY, Jeong HS, Kang JH, et al. Use of a decision aid to help caregivers discuss terminal disease status with a family member with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36):4811–4819. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Peterson B, Macri JM, Rock CL, McBride CM, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun YH, Lee MK, Bae Y, Shon EJ, Shin BR, Ko H, Lee ES, Noh DY, Lim JY, Kim S, et al. Efficacy of a training program for long-term disease- free cancer survivors as health partners: a randomized controlled trial in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7229–7235. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.12.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, Spertus JA, Herrin J, Lin Z, Phillips CO, Hodshon BV, Cooper LS, Krumholz HM. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2301–2309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Identifying/confidential patient data should not be shared.