Abstract

Systemic amyloidosis is a rare disease that can be rapidly progressive due to widespread organ involvement. There are well-described renal, cardiac, pulmonary, neurological, and dermatologic findings. Here, we outline one patient’s experience with the condition from presentation to making the diagnosis. She presented with pathognomonic dermatologic findings including pinch purpura and ecchymoses found in the skin folds.

Key words: apple-green birefringence, amyloid, amyloidosis, Congo red, inframammary erosions, periorbital ecchymoses, pinch purpura, plasma-cell dyscrasia, serum protein electrophoresis

Introduction

Amyloid is a term selected by the pathologist Rudolf Virchow in 1954 to describe the microscopic depositions he observed as being “cellulose-like” (Seldin and Skinner, 2012). Amyloidoses are a large group of diseases in which multifolding of excess proteins renders these proteins insoluble and results in deposition within organs and tissues (Falk et al., 1997, Merlini and Bellotti, 2003). Although localized and systemic forms exist, in the United States less than 10% of cases are the localized form. There are no known racial, occupational, geographic, or environmental predispositions to this condition (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012). The incidence of amyloidosis is unclear, but it is thought to be increasing. From 1950 to 1969, there were 6.1 cases per million, which increased to 10.5 cases per million between 1970 and 1989 (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012).

At least 26 unrelated proteins are known to form amyloid fibrils. While there is a great variety in the precursor protein fibril, diffraction studies have shown that all amyloid proteins share a similar pattern of antiparallel β-sheets with a propensity for aggregation (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012, Merlini and Bellotti, 2003). In addition to the disease-specific protein, all amyloid deposits also contain a proteoglycan, serum amyloid P, laminin, collagen IV, entactin, and apolipoprotein E (Kisilevsky, 2000). The misfolded proteins are highly organized, which is thought to be responsible for the proteins’ stability and resistance to proteolysis (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012).

The most common form of amyloidosis is amyloid light chain (AL amyloidosis), in which proteins originate from misfolded monoclonal antibody light chains. Plasma cell dyscrasia leads to the overproduction of these immunoglobulins. In these patients, 5 to 10% of bone marrow cells are plasma cells (Falk et al., 1997). Not all immunoglobulin light changes result in amyloidosis; in fact, only 12 to 15% of patients with myeloma have AL amyloidosis (Falk et al., 1997). However, more than 80% of patients with clinically significant AL amyloidosis have some form of monoclonal gammopathy (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012). These protein depositions consist of 23-kDa monoclonal Ig light chains or 11-18-kDa fragments. Although both lambda and kappa subtypes have been described, the lambda subtype is most common (Seldin and Skinner, 2012).

Case Summary

A 66-year-old woman was referred by her cardiologist to the department of dermatology with a 2-month history of nonhealing, inframammary lesions (Fig. 1). These lesions initially presented as erythematous patches that progressed to erosions. They were intermittently productive of a grey exudate. The lesions were asymptomatic with the exception of mild burning when applying nystatin powder, which failed to produce clinical improvement. The patient denied pruritus. The patient was in her usual state of good health until 3 to 4 months before her presentation, when she started to experience worsening shortness of breath with exertion. She was found to have a host of arrhythmic issues such as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (treated with catheter ablation), and sick sinus syndrome. The patient suffered from severe diastolic heart failure with New York Heart Association class III symptoms that was increasingly unresponsive to diuretic therapy. She was found to have severe left ventricular hypertrophy on her echocardiogram without any clinical history of hypertension. Her electrocardiogram showed slightly diminished voltage in the limb leads.

Fig. 1.

Ecchymoses and erosions in the inframammary region. Note how the skin at the inframammary crease is intact whereas skin where friction is likely to be applied is most affected.

On exam, the patient had three oval-shaped erosions, two located in the left inframammary region and one in the right inframammary region, ranging in size from approximately 2 cm × 1 cm to 4 cm × 3 cm. The bases were bright red and without exudate. Purpura were present adjacent to the ulcers but were present and more prominent on the adjoining skin of the breasts. The skin at the inframammary crease was clear, and no satellite lesions were appreciated (Fig. 1). The patient was also found to have purpura of the medial half of the left upper eyelid (Fig. 2). Further questioning revealed a 2-month history of intermittent eyelid purpura that occurred bilaterally but with a predilection for the left eyelid.

Fig. 2.

Waxy ecchymosis on the medial portion of the left upper eyelid. With the appropriate history, this may represent a pinch purpura classically described as a waxy, indurated, plaque after minor trauma.

Laboratories included b-type natriuretic peptide 1457 pg/mL, troponin I 0.28 ng/mL (Positive 0.05-0.49 ng/mL), Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) 49 mg/dl, creatinine 1.4 mg/dl, and albumin 3.5 g/dl. No monoclonal protein was detected in the serum; however, serum immunofixation identified three precipitin bands, one against immunoglobulin-G heavy chains and 2 against lambda light chains.

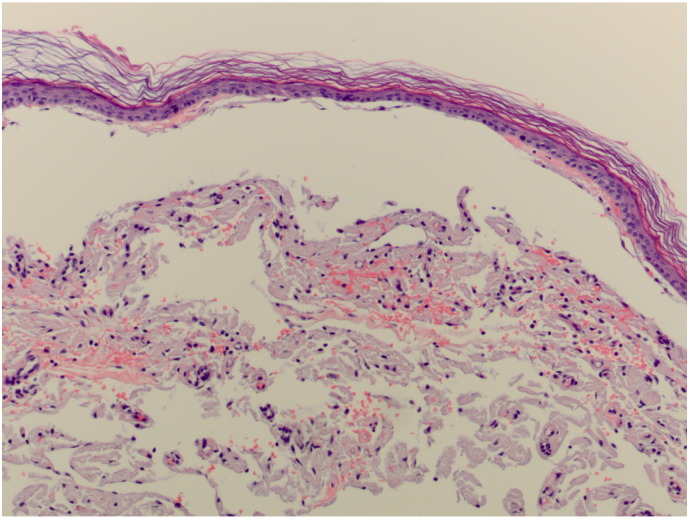

Hemotoxylin and eosin staining of two punch biopsies revealed amorphous, faintly eosinophilic material in the dermis, which was suspicious for amyloidosis (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The diagnosis of amyloidosis was confirmed by apple-green birefringence on polarization and positive staining for Congo red (Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin slide from a punch biopsy showing amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. There appears to be increased pigmentation in the basal layer of the epidermis.

Fig. 4.

Close up of the previous slide showing amorphous deposition of eosinophilic material. Classically, these depositions are found within the papillary dermis.

Fig. 5.

Congo-red stain highlighting the deposition of amyloid protein.

Fig. 6.

Congo-red stained slide under polarization demonstrating apple-green birefringence of the misfolded amyloid protein.

The patient has completed a chemotherapy regimen, which included cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone, and bortezomib to treat her multiple myeloma and AL amyloidosis. She has had a good response. Her lambda light chain has decreased from 1099 mg/L to normal range approximately 5 months after treatment. She still experiences substantial fatigue and shortness of breath with exertion. She continues to have periodic episodes of purpura affecting the eyelid and the inframammary region but rarely develops erosions.

Discussion

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of amyloidosis is based on clinical suspicion and a tissue biopsy showing protein deposition. The recommendation is a punch biopsy of subcutaneous abdominal fat or minor salivary glands (Desport et al., 2012). Staining with Congo red will be positive in 85% of patients and apple-green birefringence will be exhibited when exposed to polarized light (Falk et al., 1997, Merlini and Bellotti, 2003). If the biopsy is positive, then the type of amyloidosis should be determined. AL amyloidosis is the most common type, and a search for plasma cell dyscrasia should be considered. This workup may include serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) to detect light chains.

SPEP reveals a monoclonal protein expansion in 50% of AL amyloidosis patients when serum alone is tested and may show expansion in 86% of patients when serum and urine are tested simultaneously (Kumar et al., 2013). If the SPEP does not reveal a spike in light chains and clinical suspicion remains high, one would then consider immunofixation and a bone-marrow biopsy. If there is no evidence of plasma-cell expansion, then consideration should be given to other forms of amyloidosis (Falk et al., 1997). Nevertheless, it is not always possible to identify a monoclonal protein, and diagnosis of AL amyloidosis is therefore occasionally based on the clinical presentation (Kumar et al., 2013).

Presentation

AL amyloidosis most frequently affects patients after the age of 50 years old, is rapidly progressive, and can present with widespread symptoms (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012). The kidneys are the most frequently affected organ. Renal involvement presents with nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, secondary hypercholesterolemia, and edema. Occasionally, amyloid is deposited in the tubules rather than the glomerulus, resulting in azotemia without proteinuria (Seldin and Skinner, 2012).

The heart is the second most commonly affected organ and accounts for 75% of deaths in AL amyloid patients (Desport et al., 2012). Cardiac involvement, as with our patient, presents as diastolic dysfunction with restrictive cardiomyopathy (Seldin and Skinner, 2012). The characteristic cardiac syndrome includes signs of biventricular congestive heart failure including peripheral edema, elevated jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly, and pulmonary congestion. The disease can also present with symptoms of low cardiac output, such as fatigue, weakness, and dizziness (Falk et al., 1997). Systolic function may be preserved until late in the disease course (Seldin and Skinner, 2012). Cardiac involvement can also include conduction disorders, arrhythmias, or coronary artery disease (Desport et al., 2012).

The patient’s cardiac and dermatological symptoms began simultaneously. An estimated 40% of systemic amyloidosis patients have dermatologic findings and are more closely associated with Amyloid Light-Chain (AL) amyloidosis, followed by Transthyretin-related amyloidosis (ATTR) (familial or transthyretin-related amyloidosis) and AA (secondary amyloidosis) (Campbell et al., 2011). The majority of skin findings are thought to be caused by hemorrhage secondary to amyloid protein infiltration of blood vessel walls. Thus, we often see the stigmata of vascular involvement, including petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses (Kumar et al., 2013). These hemorrhagic skin findings are called amyloid purpura (Colucci et al., 2014) or pinch purpura (Kisilevsky, 2000) and can present as waxy indurations anywhere on the body after even minor trauma (Falk et al., 1997). Flexural regions are most commonly involved, including the eyelids and inframammary regions (Kumar et al., 2013). Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses, or raccoon eyes, are almost pathognomonic for amyloidosis, although the differential diagnosis also includes basilar skull fracture and neuroblastoma (Colucci et al., 2014).

Other less common dermatologic manifestations of systemic amyloidosis have been described, including nonhealing ulcers, bullae, macroglossia, nodules, plaques, papules, telangiectasias, hyperpigmentation, infiltrate similar to scleroderma, alopecia, nail dystrophies, cutis laxa, and even a blue skin tint (Campbell et al., 2011, Chandran et al., 2011, Kumar et al., 2013).

In addition to hemorrhagic skin lesions, more severe skin or internal bleeding can occur due to coagulation factor inhibitory circulating paraprotein, hyperfibrinolysis, platelet dysfunction, or isolated acquired factor X deficiency (Colucci et al., 2014).

Nervous system involvement may present with sensory neuropathy and/or autonomic dysfunction. Patients may complain of dysthesias, postural hypotension, impotence, and disruption of gastrointestinal motility (Merlini and Bellotti, 2003). Rarely, gastrointestinal symptoms manifest as malabsorption or pseudo-obstruction (Merlini and Bellotti, 2003). Hepatic and splenic involvement may include organomegaly and decreased functionality. Macroglossia with indentations on the tongue or an immobile tongue is pathognomonic for AL amyloidosis and affects 10 to 20% of patients (Merlini and Bellotti, 2003, Seldin and Skinner, 2012). Enlargement of the tongue can create pressure against the teeth, leaving indentations in the tongue. Amyloid deposition into soft tissue can include synovial disposition leading to the shoulder pad sign (Merlini and Bellotti, 2003), nail dystrophies, and alopecia (Merlini and Bellotti, 2003, Seldin and Skinner, 2012).

Treatment

The treatment of AL amyloidosis includes chemotherapy to treat the underlying cause of amyloid protein production and supportive care for affected organ systems.

Summary

Amyloidosis should be considered in patients with dermatologic findings including purpura, macroglossia, and/or periorbital ecchymoses, especially in the setting of concurrent unexplained cardiomyopathy, nephropathy, and/or neuropathy. Although macroglossia and periorbital ecchymoses are specific for amyloidosis, they occur in the minority of amyloidosis patients. The prognosis of amyloidosis remains poor, and determining and treating the underlying cause is the cornerstone of treatment (Lachmann and Hawkins, 2012). Minimizing morbidity and mortality in amyloidosis patients requires maintaining a high degree of suspicion to allow for the earliest possible diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Syril Keena T. Que.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: None

Disclosures of interest: None

References

- Campbell M., Rosenthal A., Kundranda M., Pickert A., Dicaudo D., Dogan A. The blue man: a novel cutaneous manifestation of systemic amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2011;18:156–159. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.571318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran N.S., Goh B.K., Lee S.S., Goh C.L. Case of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis with protean clinical manifestations: lichen, poikiloderma-like, dyschromic and bullous variants. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1066–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci G., Alberio L., Demarmels Biasiutti F., Lämmle B. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. An often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249–252. doi: 10.5482/HAMO-14-03-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desport E., Bridoux F., Sirac C., Delbes S., Bender S., Fernandez B. Al amyloidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:54. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk R.H., Comenzo R.L., Skinner M. The systemic amyloidoses. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:898–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky R. The relation of proteoglycans, serum amyloid P and apo E to amyloidosis current status, 2000. Amyloid. 2000;7:23–25. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Sengupta R.S., Kakkar N. Skin involvement in primary systemic amyloidosis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013;5:e2013005. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann H.J., Hawkins P.N. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith L.A., Katz S.I., Gilchrest B.A., editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 8th ed. The McGraw-Hill Companies; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Merlini G., Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin D.C., Skinner M. Amyloidosis. In: Longo D.L., Fauci A.S., Kasper D.L., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. The McGraw-Hill Companies; New York: 2012. pp. 945–950. [Google Scholar]