Abstract

Given the severe shortage of physicians in Israel, the Ministry of Health issued a decree that offered advanced authority and responsibilities to experienced nurses; thus, the status of the nurse specialist (NS) was created. The role of NS in Israel is truly varied, incorporating many different facets that range from stabilizing to changing the existing palliative care (PC) orders, including those involving dosages and methods of care provision, issuing of repeat prescriptions, suspending drug treatment, and prescribing new drugs for a patient according to a protocol issued by a physician. The NS is also authorized to perform many clinical duties that frequently involve direct patient care. According to the different needs of the patients, he/she coordinates with the different members of the interdisciplinary team, who may be suitable to offer further help and support to the client and/or his/her significant others. His/her work keeps him/her in a constant dialogue with other health-care professionals, and as questions arise, he/she answers them and offers support to staff, patients, and family members. In the Middle East, the whole issue of PC is relatively new, and due to cultures, traditions, and religions, a number of difficulties have to be resolved.

Keywords: Israel, palliative care, role of clinical nurse specialist, shortage of doctors

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) is a relatively new discipline in the Middle East and considerably remains in the process of development in the region. Given the fact that health professionals, cancer patients and the public at large were not understanding what PC is about, there have been misunderstandings, misgivings, and confusion that are in part associated with cultural, traditional, and religious aspects of life. The term PC itself has not aided the understanding as it has not been obvious in communicating exactly what the clinical discipline has to offer in the manner of improving the quality of life of the patients.[1]

In Israel, a rising awareness of the specialty of PC has occurred since the late 1970s,[2] and throughout the succeeding years, the development has continued in various places within Israel.[1]

In the year 2009, the Israeli Ministry of Health (MOH) decided to develop PC services in the whole land of Israel. The services were to be rendered in hospitals, nursing facilities, and the community.[3] This decision was related to a severe shortage of physicians in Israel,[4,5,6] and it lead to augmenting the authority and responsibilities of nurses.[4]

In many countries worldwide, advanced practice providers have been integrated into health-care systems to cover the following: shortage of available physicians; need for improved access or delivery of services; need to provide services in regions that are underserved; and to keep costs down.[5]

Aaron and Scheinberg Andrews[5] helped to clarify the term of the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) linguistically. In Hebrew, the term “Clinical Nurse Specialist” is used but the scope of practice for the new Israeli role is closer to the international description of a nurse practitioner, as the emphasis of his/her work is on direct patient care.

As one of the steps for implementing the plan to acquire PC on a national basis, the MOH initiated a selection process interviewing nurses with experience in PC that were to become part of the pioneering group of CNSs in Israel. Riba, the former head of the Israeli MOH's nursing division, presented the following explanations: “We are talking about a very senior nurse who is independent in administering treatment and generally deals with less complex and more chronic patients, such as those who require long-term monitoring.”[7] Thus, after a careful selection process, these professionals, that had undergone advanced training in various settings, were granted recognition as CNSs.[8]

In January 2010, these nurses received a certificate that authorized them to work in their new roles in hospitals, nursing homes, or community. They have the authority to stabilize and change existing PC orders, including those involving dosages and methods of care provision.[4] This pertains to PC patients in their homes, in PC clinics, or oncological patients receiving care in the community.[9]

Two universities in Israel are developing formal academic programs, and a licensing examination for the graduates will occur in the future.[2] Silberman et al.[1] added that there are 1- or 2-year diploma courses offered at some of the universities for physicians, nurses, and social workers.

The actual form of the role of the Nurse Specialist (NS) in the hospital depends on the way the nurse develops it within the context of his/her work setting. He/she works as a consultant and expert nurse and is given the authority to perform his/her role by the institution he/she is working at.[10] In practice, the NS has had the opportunity to write her own job description according to the evolving service that was rendered. With the help of keeping a detailed record of all the different assignments that she was called to attend to over the last year and a half, the role started to become clearer.

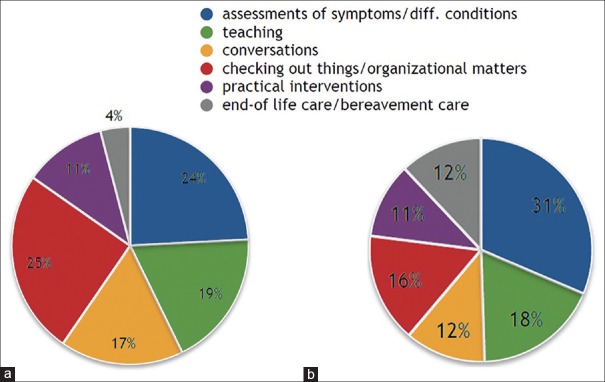

The following charts show the results of the evaluation of the statistics:

Assessing the patients’ conditions and symptoms

Teaching patients, their families, and the staff

Conversations that cover the whole span of answering questions to speaking about the illness and topics related to the matter or giving emotional support to patients, their families, and members of staff

Organizational matters can range from organizing a complex discharge of a patient, including teaching the family members how to use a central line in a home setting to contacting community care and getting things organized with their services

Practical interventions: For example, giving a patient pain medication or feeding someone to spend time and have a lengthy conversation with him/her in a quiet setting or draining a pleural effusion via an indwelling catheter

End of life and bereavement care entails offering support to the patient, his/her family, and the staff surrounding the preterminal and terminal phase in a patient's life and also after his/her death [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Data of 7 months of activity in 2015. (b) In the 10 months thus far, in 2016, the picture looks a little different

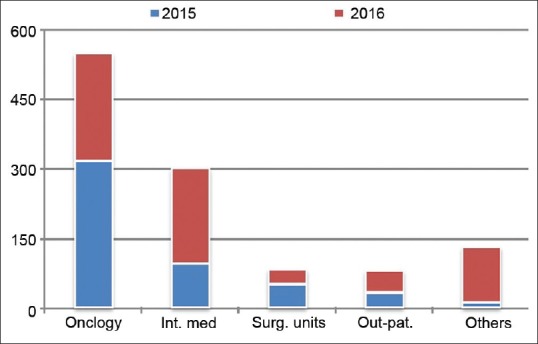

Moreover, the needs of the various teams within the hospital have become more evident. In 2015, the Oncology/Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit were the departments that requested most of the NS's visits. In 2016, changes were to be observed as the service became increasingly popular [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Requests for PC-visits from the different units at the hospital in the years 2015 (7 months) and 2016 (10 months)

This article is a short report on how the role developed and will give some insight on the needs of patients, their caregivers, and the various members of staff involved in their care.

A Personal Report

I have worked in the oncology unit for a number of years as a PC nurse alongside being a regular member of the staff there. The team of the oncology unit has been accustomed to the whole topic of PC over time. In the rest of the hospital, not so much of an awareness of what PC can offer for the well-being of the patients exists.[11]

With the new law in operation, the health care system started to organize itself. In our hospital, a multi-disciplinary PC team consisting of a number of medical doctors, some nurses, a social worker, and a psychologist was formed in November 2014. Some of the doctors in the team are oncologists, we have a hematologist, a nephrologist, a physician from the Intensive Care Unit, and an anesthesiologist. Three members of the team belong to the pain team. The nurses involved are working in the pain clinic, one NS works in the Children's Hospital and one NS has been allocated 18 hours per week in the rest of the hospital, in which she attends to patients who need symptom management or wound assessments (mainly bed sores and cancer-related wounds) or support in the phase of the end of life, and so on.

Silberman et al.[1] talked about the challenges that go with introducing PC services into the local Israeli setting: one point is the raising of awareness and knowledge regarding PC among health care professionals. Brittany[1,12] appropriately describes that PC needs to begin at the bedside, one patient at a time, and the PC team needs to show everyone what they can offer in the way of helping. It is similar to a private practice setting wherein health care professionals must be available at all times, attending to all arising needs and also being palliative for the other staff members.

Peterson et al.[13] supported the above statement concerning the staff who is also in need of PC/support. They showed that communicating with patients and their families, as well as with co-workers, is an integral part of how nurses cope with death and dying. This was confirmed in our experience: once the PC team became more known and what it and the NS have to offer, requests for visits have started to become progressively frequent. Several members of the staff have also started to share with the NS what they are experiencing with their patients either in their wards or in their private lives in connection with death and dying.

All of this has taken months to develop. Connell et al.[14] found that patient symptom control and education for carers on symptom control and on how to provide care help to maintain the patient's and the carer's psychological health. As part of her work, the NS assesses the patient's needs (symptoms, general condition, social, psychological, and spiritual) and then turns to other members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) to ensure that the patient receives the best possible care. MDT in the local setting includes social workers, psychologists, dieticians, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, a doctor who specialized in alternative medicine, and a score of volunteers that are willing to help with various things. Concerning spiritual support for our patients, potential for further development of the topic exists.

A number of our patients need symptom relief due to pleural effusions or ascites. These are mostly oncological patients, and some have received an indwelling, under tunneled catheter that enables the draining of troubling liquids by the caregivers in a home setting. Fleming et al.,[15] Bertolaccini et al.,[16] and Mullard et al.,[17] confirmed that such catheters can be useful for symptom control and improvement of the quality of life.[17] Recently, in one of the internal medical units, a 92-year-old female needed such a catheter to be able to go home and spend the rest of her life with her family outside of the hospital. Thus far, she needed to undergo thoracentesis every three days and she was not mobile. The treating physician and NS gathered with the family, and finally, they arrived at a point in the conversation where it became vital to inform the family that this patient was in the possibly few remaining months of her life and that these were important times for preparation and closure. The family accepted the message and a new level of trust was established between them and the medical staff. The daughters were given instructions on how to use the catheter and numerous other questions were asked and answered. This conversation also changed the relationship between the treating physician and the NS in a positive way.

Conclusion

The role of the NS is a varied and an innovative one. The nurse has a unique opportunity to help improve the quality of life of the patients, caregivers, and also the staff involved. Much teaching is conducted on the role, which is a highly rewarding and fulfilling assignment, involving the goal of making a positive difference in the lives of the patients, their families, and other caregivers and also the hospital staff.

Potential development of the services can occur when further funds can be allocated to the broadening of the service. At this stage, further studies are needed in connection with the development of the administration of PC services and their implementation and the role of the NS in the Israeli setting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, Nestoros S, Pitsillides B, Charalambous H, et al. Palliative cancer care in middle Eastern countries: Accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):15–28. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livneh J. Development of palliative care in Israel and the rising status of the clinical nurse specialist. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(Suppl 2):S157–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230e22f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nursing Administration Circular Expert Nurse in Palliative Care. Ministry of Health, Jerusalem. 2009. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 01]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.il/hozer/ND79_09.pdf .

- 4.Ben Natan M, Oren M. The essence of nursing in the shifting reality of Israel today. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaron EM, Scheinberg Andrews C. Integration of advanced practice providers into the Israeli healthcare system. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:7. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Even D. Health Ministry Warns of Shortage of Doctors, Nurses: Haaretz Newspaper. 2010. [Last retrieved on 2016 Nov 18]. Available from: http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/health-ministry-warns-of-shortage-ofdoctors-nurses-1.300230 .

- 7.Even D. More Nurses to be Trained to Take on Doctor's Duties, Health Ministry Plans. [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 17];Haaretz Newspaper. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentur N, Emanuel LL, Cherney N. Progress in palliative care in Israel: Comparative mapping and next steps. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2045-4015-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nursing Administration Circular Nursing Activities in Palliative Care. Ministry of Health, Jerusalem. 2011. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 01]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.il/download/forms/a3861_ND-88int.pdf .

- 10.DeKeyser Ganz F. Nurses Given the Authority to perform their Roles by the Institutions they Work in. Advanced Practice Nursing in Israel. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.international.aanp.org/content/docs/APN_In_Israel.pdf .

- 11.World Health Organization Definition of Palliative Care. 2002. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en .

- 12.Brittany MP. How does the pain and palliative care service function within the NIH clinical center? NCI Cancer Bull. 2010. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 01]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/ncicancerbulletin/032310/page6 . [No accessing possible on 27.11.2016. Reference taken from Silberman et al. (2012)]

- 13.Peterson J, Johnson M, Halvorsen B, Apmann L, Chang PC, Kershek S, et al. Where do nurses go for help? A qualitative study of coping with death and dying. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010;16:432–434. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.9.78636. 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connell T, Fernandez RS, Griffiths R, Tran D, Agar M, Harlum J, et al. Perceptions of the impact of health-care services provided to palliative care clients and their carers. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010;16:274–84. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.6.48829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming ND, Alvarez-Secord A, Von Gruenigen V, Miller MJ, Abernethy AP. Indwelling catheters for the management of refractory malignant ascites: A systematic literature overview and retrospective chart review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertolaccini L, Viti A, Gorla A, Terzi A. Home-management of malignant pleural effusion with an indwelling pleural catheter: Ten years experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullard AP, Bishop JM, Jibani M. Intractable malignant ascites: An alternative management option. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:251–3. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]