Internationally, family members or spouse caregivers are critical in maintaining and improving the quality of life of individuals living with cancer.[1] By providing about 70%–80% of patients’ cancer care, informal caregivers reduce the demands on the health-care system, with significant economic benefits.[2] Despite their value to society and economy, caregivers remain largely a hidden workforce, taking on their important roles and responsibilities with little to no formal training. This lack of formal training leads to high levels of burden and lower quality of life for not only the caregiver but also the person they are caring for.[1] Cancer caregivers have been found to report higher burden than caregivers for individuals with diabetes or frail elders, highlighting their particular vulnerability.[3]

Caregivers’ Unmet Needs

The responsibility that caregivers take on has, in turn, prompted in-depth documentation into the kind of support they need, which is also referred to as unmet supportive care needs. Unmet needs assessments can inform intervention development and the prioritization of resources to address key deficiencies in services. A recent systematic review we completed[4] found that 16%–68% of caregivers report unmet supportive care needs, with an average of 1.3–16 unmet needs (possible maximum range = 17–67) identified. Such rates of unmet supportive care needs exceed those reported by the patients. Caregivers in the acute postdiagnosis phase or advanced phase of the illness were found to be at particularly high risk of reporting unmet needs.[4] Our review identified that caregiver needs fall into the following domains: comprehensive cancer care, emotional and psychological, impact and daily activities, relationship, information as well as spirituality.[4] The unmet needs that were reported in at least one study by more than 60% of caregivers included being told about the help health-care professionals can offer; having the opportunity to participate in patient's care; having a supportive relationship with health-care professionals; having access to health services; dealing with one's own emotional distress; getting emotional support for oneself; accessing financial support; maintaining a sense of control; knowing what to expect; and having information about the illness, treatment, death, and dying, in addition to providing patient care. Unmet needs not only contribute to caregivers’ burden but also adversely impact on patients’ distress, anxiety, and depression.[4]

Although several studies have documented caregivers’ unmet needs, a key limitation is the use of a cross-sectional design, providing limited information on how caregivers’ unmet needs change as they confront different challenges along the illness trajectory. To address this gap in literature, our team recently concluded a longitudinal study of partners’ and caregivers’ well-being and used the Supportive Care Needs Survey – Partners and Caregivers (SCNS-P and C)[5] to identify caregivers’ (n = 547) unmet needs at 6, 12, and 24 months postdiagnosis.[6] One important finding was that six unmet needs ranked in the top (based on their prevalence) across time: managing concerns about cancer coming back, reducing stress in the person with cancer's life, understanding the experience of the person with cancer, more accessible hospital parking, balancing the needs of the person with cancer and yours, and addressing problems with sex life. It is reasonable to recommend that interventions should assist caregivers with these core needs. A second important finding was that a shift in the types of unmet needs reported at 12 and 24 months (in comparison to those reported at 6 months) was noted, with needs related to caregivers’ well-being and relationships (e.g., impact that cancer has had on your relationship with the person with cancer) taking priority over some patient-focused needs (e.g., obtaining best medical care). This shift notes an increased interest by caregivers in processing and managing the impact of the cancer on themselves. This finding suggests that caregiver interventions might need to take into consideration where the caregiver is at along the illness trajectory. In this study, variables associated with reporting more unmet needs were high interference in daily activities, anxiety, and avoidant and active coping. Although active coping is generally associated with enhanced patient outcomes, caregivers may not have had as many opportunities to develop these skills.

How Effective are Caregiver Interventions?

Now that there has been considerable research on caregivers’ unmet needs, an important question to ask is: has this research been translated into effective caregiver interventions? The ultimate goal of caregiver interventions is to reduce caregivers’ burden, anxiety, and depression, and in doing so, enhance their quality of life. The development of caregiver interventions is typically guided by stress and coping theories or principles of cognitive behavioral therapy,[7] whereby it is assumed that addressing caregivers’ needs in a way that is timely and adaptive will result in improved outcomes for caregivers. A 2010 meta-analysis[7] found that 23 of the 29 caregiver interventions reviewed focused on psychoeducation and skills training. These interventions (a) provided disease information, (b) developed caregivers’ coping and self-management skills to optimize patient care (e.g., symptom management) or their own health (e.g., stress management), (c) strengthened patient-caregiver mutual support, and/or (d) connected caregivers to resources. Typically, these interventions addressed a selected number of unmet needs depending on the subgroup targeted. For instance, a psychoeducation intervention by Giarelli et al.[8] for spouses of men following prostate surgery focused mostly on emotional and psychological needs (e.g., stress management), partner impact and daily activities (e.g., role adaptation, illness management tasks), relationship needs (e.g., communication), and information needs (e.g., providing direct care to patient). Across published caregiver interventions, there is a consensus that these domains of needs are essential; however, this has, in part, excluded the comprehensive cancer care unmet need domain. Furthermore, within these domains, there is greater variability regarding which individual need items should be addressed. Overall, caregiver interventions have been found to have significant impact on proximal outcomes, including information needs (effect size [ES] =1.36), coping (ES = 0.47), self-efficacy (ES = 0.25) as well as distal outcomes of anxiety (ES = 0.20), burden (ES = 0.22), and relationship functioning (ES = 0.20).[7] Caregiver interventions have been less successful in affecting caregiving benefit (ES = 0.17), physical functioning (ES = 0.11), depression (ES = 0.06), and social functioning (ES = -0.14). Although the Northouse et al.[7] meta-analysis did not find that intervention type was a moderator of efficacy, systematic reviews since published have found that focusing on communication and/or problem-solving skills training enhanced intervention efficacy.[9,10] This finding emphasizes that if caregivers develop the problem-solving skills required to address any challenge or need, they are not reliant on the specific content of the intervention that might or might not be relevant to them.

Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Caregiver Interventions

Although caregiver interventions have a significant positive effects on numerous outcomes,[7] many ESs are small (<0.30). This is comparable to psychosocial interventions with the patients themselves. There are a number of reasons to explain these results, including small sample sizes (and lack of power), inclusion/exclusion criteria of the participants (e.g., baseline anxiety), selected outcomes and measures (e.g., lack of responsiveness), high attrition, and content of the intervention. We will further discuss attrition and content of the intervention as these limitations are related to the concept of unmet needs.

Approximately, one-third (range=9%–49%) of caregivers who begin a caregiver intervention do not complete it.[11] Commonly, attrition is due to high patient symptom severity or high caregiver burden and strain. Another reason is that the intervention does not meet caregivers’ needs. Many caregiver interventions are based on a theoretical framework to determine their mechanism of action; fewer rely on a systematic needs assessment or an evidence-based list of caregivers’ unmet needs to determine content. Therefore, it might be a hit or miss whether the intervention in fact addresses caregivers’ most pressing needs. One suggestion is to tailor interventions to caregivers’ needs to increase the likelihood of positive outcomes. With the increased use of online platforms, tailoring content based on most prominent unmet needs is becoming more feasible. A related aspect is that most interventions overlook the learning process that caregivers must undertake to acquire the information and skills required to meet their needs. Therefore, other promising tailoring variables to consider in future caregiver interventions include caregivers’ learning preferences (e.g., type and amount of information, learning style) and their readiness to learn. Some interventions do address caregivers’ prevalent unmet needs, but content might be released over time in the form of modules, which means that caregivers might have to wait several weeks before the most relevant module to them is offered. The implication of a time-dependent and content-based approach is that those caregivers in need of most support might withdraw from an intervention that is not offering immediately what they require.

Reliance on an evidence-based list of prevalent unmet needs points to several foci for caregiver interventions. However, such an approach to content development assumes that addressing these needs will directly result in improving outcomes such as anxiety, depression, burden, and/or quality of life. A limitation of this approach is that the relationship between individual unmet needs and these outcomes has not been examined. Most studies to date have examined the relationship between caregiver outcomes and a composite score of unmet needs. Most commonly, this has included unmet need count (e.g., the number of individuals experiencing at least one unmet need) or unmet need domain mean scores. This scoring system overlooks the potential significance of individual unmet need items and to a certain extent, assumes that the burden or anxiety created by an unmet need is equal to that of any other unmet need. The significance of different unmet needs and the impact of addressing these (regardless of prevalence) remains a gap in this field. With unmet needs questionnaires typically including more than 19 items, the very large sample sizes required to reliably explore this issue through regression analyses might be the main barrier. However, statistical methods such as using partial least square (PLS) to narrow the list of significant unmet needs or applying tree analysis to provide a clearer picture of the profile of unmet needs most likely to lead to adverse outcomes could be used.

Using the data from our partner and caregiver study and PLS, we identified that of the 45 items of the SCNS-P and C, 20 were significantly related to anxiety (variable importance in projection [VIP] >1.0[12]) at 6 months. The majority of the core needs mentioned above were significant; however, unmet needs that do not satisfy the prevalence cut-off were also found to be significant (e.g., look after your own health). In fact, “make decisions in the context of uncertainty” had the highest VIP but is not in the top 10. Because this type of need typically does not meet the prevalence cut-off, it is not often addressed by current caregiver interventions. The implication of this finding is that even if an intervention addresses the most common unmet needs, neglecting those needs most associated with anxiety might undermine the actual efficacy of the intervention.

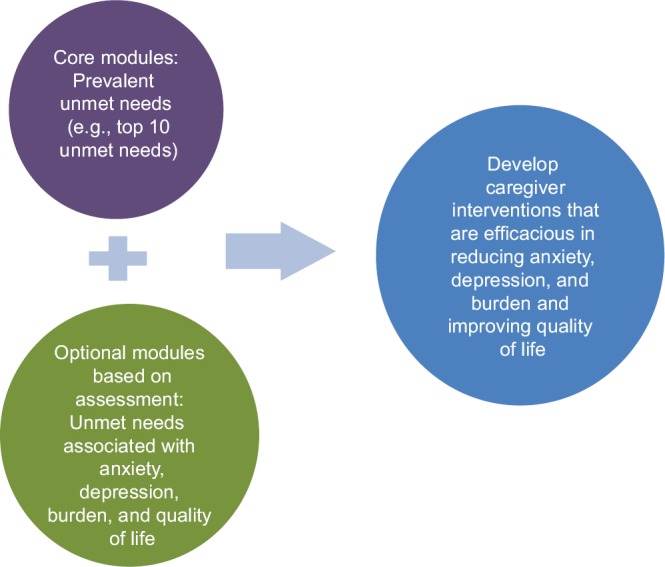

In conclusion, our recommendations in integrating the unmet needs research in designing effective caregiver interventions are to: (a) tailor content according to caregivers’ most prominent needs and learning context, (b) offer the content at the time that is most relevant for caregivers (refrain from using a time-dependent, content-based approach), and (c) better understand caregivers’ most distressing unmet needs (regardless of prevalence) and integrate these in the intervention. One suggestion is for caregiver interventions to include core and optional modules. The core modules could address the most prevalent unmet needs, likely to benefit the majority of caregivers, at a time most relevant to them. The optional modules would be offered to caregivers who report unmet needs that are not necessarily frequent but that adversely impact on key outcomes [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of recommendation on the integration of core and optional intervention modules to address caregivers’ needs

Financial support and sponsorship

Dr. Lambert was funded by IPOS to attend ICCN. Dr. Lambert was also funded by a FRQS Research Scholar Award. Prof. Girgis is funded through a Cancer Institute NSW grant.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article was written on the basis of a presentation given at the International Conference on Cancer Nursing (ICCN) 2016 held in Hong Kong.

References

- 1.Lambert SD, Girgis A, Levesque J. The impact of cancer and chronic conditions on caregivers and family members. In: Koczwara B, editor. Cancer and Chronic Conditions: Addressing the Problem of Multimorbidity in Cancer Patients and Survivors. Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fast J, Niehaus L, Eales J, Keating N A profile of Canadian chronic care providers. A Report Submitted to Human Resources and Development Canada. Edmonton: Department of Human Ecology UOA; 2002. Department of Human Ecology UOA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y, Schulz R. Family caregivers’ strains: Comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. J Aging Health. 2008;20:483–503. doi: 10.1177/0898264308317533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, Bonevski B, Carey M, Lawsin C, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2:224–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C. The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncology. 2011;20:387–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girgis A, Lambert SD, McElduff P, Bonevski B, Lecathelinais C, Boyes A, et al. Some things change, some things stay the same: A longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers’ unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1557–64. doi: 10.1002/pon.3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giarelli E, McCorkle R, Monturo C. Caring for a spouse after prostate surgery: The preparedness needs of wives. J Fam Nurs. 2003;9:453–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baik OM, Adams KB. Improving the well-being of couples facing cancer: A review of couples-based psychosocial interventions. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37:250–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldron EA, Janke EA, Bechtel CF, Ramirez M, Cohen A. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of life. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1200–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan TW, Lambert SD, Girgis A, Kelly B, Kayser K, Turner J. Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? A systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akarachantachote N, Chadcham S, Saithanu K. Cutoff threshold of variable importance in projection for variable selection. Int J Pure Appl Math. 2014;94:307–22. [Google Scholar]