Abstract

Background

We examined the current status of depressive and anxiety symptoms in Japanese women during pregnancy and postpartum.

Methods

We asked 220 Japanese women who gave birth to singleton babies at term to answer the two self-administered questionnaires (Whooley’s two questions and two-item generalized anxiety disorder scale) at first, second and third trimester of pregnancy and 1 month after delivery.

Results

The rates of women with depressive symptoms were common during the first trimester of pregnancy (25%) and the postpartum (17%), while the women with anxiety symptoms were common during the first trimester of pregnancy (36%). Eight percent women had histories of mental disorders, and 95% of them showed depressive and/or anxiety symptoms somewhere during pregnancy. Of the women who had depressive symptoms during postpartum, 86% showed depressive and/or anxiety symptoms somewhere during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Screening for depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy was suggested to be useful to detect high risk women of postpartum depression.

Keywords: Depressive symptom, Anxiety symptom, Pregnancy, Postpartum, Japan

Introduction

For women of reproductive age, psychiatry regarding pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing will change rapidly [1]. Recently, perinatal mood and anxiety disorders have been the most common mental health problems among these women, and they have been associated with increased risks of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity and been recognized as significant patient safety issues [1-3]. In Japan, the subsequent maternal mortality rate as the number of deaths from suicide associated with mental disorders has been also reported to be higher than deaths due to obstetric medical conditions like other countries [4, 5].

To date, some observations have indicated that symptom levels of depression, anxiety and/or stress vary over the course of pregnancy [6, 7]. In an earlier study by Rallis et al [6], increased depression in early pregnancy was associated with later depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress in late pregnancy. The studies have indicated the importance of emotional health screening in early pregnancy.

In this study, therefore, we examined the current status of depressive and anxiety symptoms in Japanese women during pregnancy and postpartum using two self-administered questionnaires [8-10]. In addition, we examined the association between mental status during pregnancy and postpartum in Japanese women.

Methods

The protocol for this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Japanese Red Cross Katsushika Maternity Hospital. Informed consent concerning retrospective analyses was obtained from all subjects.

Between April 2016 and January 2017, we asked 220 Japanese women who gave birth to singleton babies at term at Japanese Red Cross Katsushika Maternity Hospital to answer the following two self-administered questionnaires at 8 - 12 (first trimester of pregnancy), 20 - 24 (second trimester of pregnancy), 34 - 37 weeks’ gestation (third trimester of pregnancy) and 1 month after delivery (postpartum), and 207 women (94%) gave us analyzable answers. In this study, we excluded the women complicated by mental disorders currently undergoing psychotherapies and/or medications.

The first questionnaire was the tale of Whooley’s two questions [8, 9], a screening instrument for depression in the general adult population including pregnant and postpartum women. 1) During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? 2) During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things? If at least one of the two questions is “yes”, we diagnose the woman as having depressive symptom. The second questionnaire was the two-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-2) to screen for generalized anxiety disorder [9, 10]. 3) Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious or on edge? 4) Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by not being able to stop or control worrying? If at least one of the two questions is “yes”, we diagnose the woman as having anxiety symptom.

We also retrospectively analyzed the medical charts of the pregnant women who responded these questionnaires as follows: maternal age, parity, history of mental disorders, delivery mode and the most troubled problem in 2 weeks after delivery.

For statistical analysis, the Χ2 test was used and P < 0.05 was considered significant. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.

Results

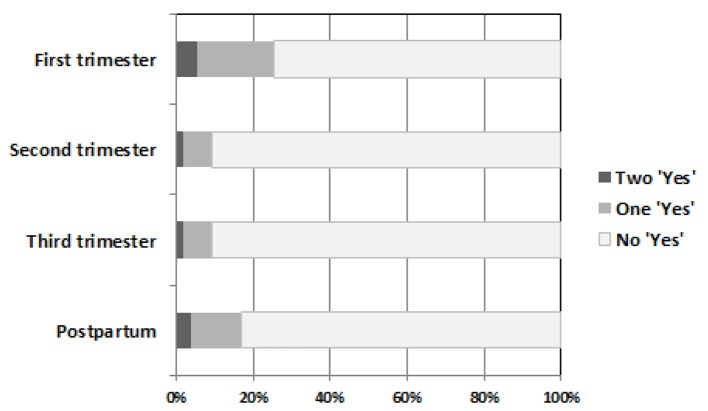

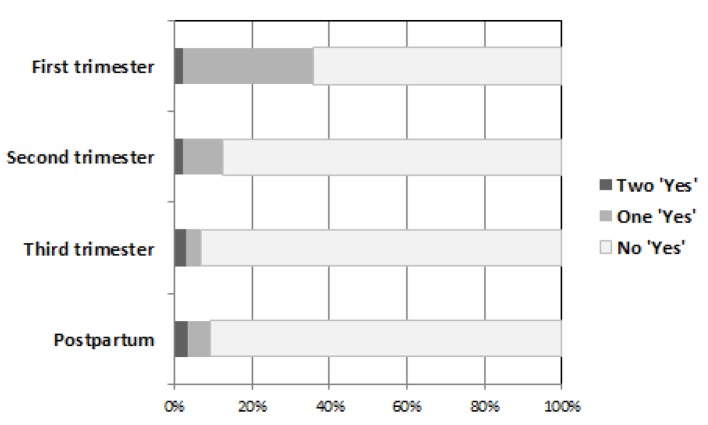

Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2 show the results of answers for the two self-administered questionnaires in this study (Figure 1 shows the results of Whooley’s two questions, while Figure 2 shows the results of GAD-2). As shown in Table 1, the women with depressive symptoms were common during the first trimester of pregnancy and the postpartum, while the women with anxiety symptoms were common during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Table 1. Results of Answers for the Two Self-Administered Questionnaires During Pregnancy and 1 Month After Delivery.

| Whooley’s two questions | Generalized anxiety disorder scale-2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 208 | 208 |

| First trimester | ||

| Yes at least one question | 53 (25%) | 75 (36%) |

| Yes to the both questions | 11 (5%) | 5 (2%) |

| Second trimester | ||

| Yes at least one question | 19 (9%) | 26 (13%) |

| Yes to the both questions | 4 (2%) | 5 (2%) |

| Third trimester | ||

| Yes at least one question | 19 (8%) | 14 (7%) |

| Yes to the both questions | 4 (2%) | 6 (3%) |

| Postpartum | ||

| Yes at least one question | 35 (17%) | 19 (9%) |

| Yes to the both questions | 8 (4%) | 7 (3%) |

Figure 1.

Results of answers for Whooley’s two questions during pregnancy and 1 month after delivery.

Figure 2.

Results of answers for the two-item generalized anxiety disorder scale during pregnancy and 1 month after delivery.

There were 16 women (8%) who had histories of mental disorders (Table 2). Of these, 10 (63%) and 13 women (81%) had depressive and anxiety symptoms during the first trimester, respectively. Fifteen of them (95%) showed depressive and/or anxiety symptoms somewhere during pregnancy.

Table 2. Women With Histories of Mental Disorders.

| Total | 16 |

| Depression | 5 |

| Anxiety disorders | 4 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 |

| Others | 3 |

Of the 35 women who had depressive symptoms during postpartum, 30 women (86%) showed depressive and/or anxiety symptoms somewhere during pregnancy, while five women (14%) showed no these symptoms during pregnancy. According to their medical charts, four of them were primiparas and were worried about the possibility of insufficient breastfeeding.

Table 3 shows the clinical descriptions and most serious troubles in the women (n = 8) who answered “yes” to the both Whooley’s two questions. Three had troubles in breastfeeding including the worrying about the possibility of insufficient breastfeeding, two had those with crying at night and two had those with neonatal congenital abnormalities. The rest one was worried without any reasons.

Table 3. Clinical Descriptions and Most Serious Troubles in the Women Who Answered “Yes” to the Both Whooley’s Two Questions (n = 8).

| Case | Maternal age (years) | Parity | Delivery mode | Most serious trouble |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | 0 | Normal delivery | Breastfeeding |

| 2 | 29 | 1 | Normal delivery | Unknown |

| 3 | 26 | 0 | Forceps delivery | Breastfeeding |

| 4 | 36 | 0 | Elective cesarean delivery | Breastfeeding |

| 5 | 35 | 1 | Normal delivery | Neonatal congenital abnormalities |

| 6 | 39 | 0 | Elective cesarean delivery | Neonatal congenital abnormalities |

| 7 | 30 | 0 | Normal delivery | Crying at night |

| 8 | 36 | 0 | Normal delivery | Crying at night |

Discussion

Depression and anxiety have been reviewed to be the most common mental health problems in perinatal period. These had been observed to affect about 10 - 15 out of every 100 pregnant women [2, 3]. In our current study, the incidence of depressive and/or anxiety symptoms has been observed to be about 20-35% in the women during the first trimester of pregnancy. The reliability accuracy of the current two questionnaires for Japanese women may be unclear; however, the current frequencies may indicate that the mental status of Japanese women at the period is unstable with various physical and/or social changes associated with pregnancy. In addition, the levels of general and maternal anxiety have been observed to be high at first trimester and become low towards the end of pregnancy in Japan [11, 12]. The current results seemed to support these previous studies [2, 3, 11, 12].

The current results can support the relation between the mental health problems in the past and those during pregnancy reported previously [2, 7]. In addition, the current results also seemed to support the previous reports those women with postpartum depressive symptoms usually had some psychiatric symptoms before and/or during pregnancy [2, 6, 13]. In this study, in addition, the main worried troubles in the women with postpartum depressive symptoms were those concerning their infants. Some previous studies consistently have shown that mothers of unhealthy infants experience postpartum depression at higher rates with more elevated symptomatology than mothers of healthy infants [14, 15]. The feeling of lactation shortage during the early postpartum period has been observed to cause the mother’s self-confidence relating to the incidence of postpartum depression in Japan [16, 17]. In addition, a connection between depression and poor sleep among postpartum mothers associated with the feeling of lactation shortage has been observed [18].

In this study, we examined the current status of depressive and anxiety symptoms in pregnant and puerperal Japanese women. Screening for depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy was suggested to be useful to detect high risk women of postpartum depression. In addition, the assessment of past histories concerning mental disorders and neonatal status is important for perinatal mental health care.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, Kay LB, Miller ES, Moore Simas TA, Frieder A. et al. Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health: Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):422–430. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Mental health in pregnancy. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/mentalhealthinpregnancy.aspx (February 13, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamo T. [Perinatal Depression: The Meaning of the Paradigm Shift from "Postnatal" to "Perinatal"] Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2015;117(11):902–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeda S. Challenge to maternal death 'zero' (in Japanese) Nippon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 2016;68(9):1815–1822. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rallis S, Skouteris H, McCabe M, Milgrom J. A prospective examination of depression, anxiety and stress throughout pregnancy. Women Birth. 2014;27(4):e36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okano T. Pregnancy, delivery and clinical psychiatry practice (in Japanese) Jpn J Psych Treat. 2013;28:545–551. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. Clinical guideline [CG192]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (Published date: December 2014, Last updated: June 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niimi Y, Tukada T, Kamigori H. Anxiety of pregnant women: Transition of anxiety during pregnancy and the way of health guidance (in Japanese) J Nurs Soc Toyama Med Pharm Univ. 1993;2:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwamoto S, Nakamura M, Yamashita H, Yoshida K. Impact of situation of pregnancy on depressive symptom of women in perinatal period (in Japanese) J Natl Inst Public Health. 2010;59:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bicking C, Moore GA. Maternal perinatal depression in the neonatal intensive care unit: the role of the neonatal nurse. Neonatal Netw. 2012;31(5):295–304. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.31.5.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(3):230–237. doi: 10.1007/s10880-010-9202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamazaki K, Takagi H, Kubo K, Masuda T. Astudy on fatigue during the early puerperium and its associated aggravating factors (in Japanese) Jpn J Mater Health. 2016;57(2):314–322. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okano T, Minamida T, Kokubu M. Treatment of postpartum depression (in Japanese) Obstet Gynecol Ther. 2010;101(4):375–379. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CM, Carter PA, Guo JL. A comparison of sleep and daytime sleepiness in depressed and non-depressed mothers during the early postpartum period. J Nurs Res. 2004;12(4):287–296. doi: 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387513.75114.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]