Abstract

Background:

Approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond adequately to their antidepressant treatment, underscoring the need for more effective treatment options. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of adjunctive brexpiprazole on depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder who were not responding to adjunctive or combination therapy of their current antidepressant treatments with several different classes of agents (NCT02012218).

Methods:

In this 6-week, open-label, phase 3b study, patients with major depressive disorder who had an inadequate response to ≥1 adjunctive or combination therapy, in addition to history of ≥1 failure to monotherapy antidepressant treatment, were switched to adjunctive brexpiprazole. Efficacy was assessed by change from baseline to week 6 in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score. Patient functioning was assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale and the Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire. Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

Results:

A total of 51/61 (83.6%) patients completed 6 weeks of treatment with adjunctive brexpiprazole. Improvements in depressive symptoms were observed (least squares mean change from baseline to week 6 in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score, −17.3 [P < .0001]) as well as improvements in general and cognitive functioning (mean changes from baseline to week 6: Sheehan Disability Scale, −3.1 [P < .0001]; Massachusetts General Hospital–Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire, −9.2 [P < .0001]). The most common adverse event was fatigue (14.8%); akathisia was reported by 8.2% of patients.

Conclusions:

In patients with major depressive disorder who had switched to open-label adjunctive brexpiprazole following inadequate response to previous adjunctive or combination therapy, improvements were observed in depressive symptoms, general functioning, cognitive function, and energy/alertness.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, brexpiprazole, adjunctive, switching, antidepressant

Introduction

Despite sufficient availability of current antidepressant treatments (ADTs), approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not respond adequately to treatment, and only 35% to 40% of patients will experience remission of symptoms in the initial 8 weeks of treatment (Fava, 2003; Papakostas, 2009). A recent self-report survey of adult patients with MDD who were receiving ADT revealed that of 5988 patients who were assessed, 31.2% experienced a partial response to their ADT and 37.9% were classified as nonresponders (Knoth et al., 2010). Additionally, patients with MDD who were classified as having inadequate response (partial or no response) to their ADT were more likely to be associated with loss of work productivity in employment or a low likelihood of current employment (Knoth et al., 2010). As such, MDD is a challenging condition to treat and there is a need for novel, effective MDD treatments.

Treatment strategies for patients with MDD who experience inadequate response to their ADT include increasing ADT dose, switching to another ADT, combining current therapy with another ADT (combination therapy), or augmentation with a non-ADT, such as an atypical antipsychotic, stimulant, or bupropion (Fava, 2001; Fava and Rush, 2006; Connolly and Thase, 2011). However, no clear consensus currently exists on which treatment strategy is the most effective for patients with MDD who do not respond adequately to treatment (Connolly and Thase, 2011), particularly for those with inadequate response to adjunctive treatment strategies.

Findings from the STAR*D study showed that a high proportion of patients with MDD not only experience suboptimal outcomes to citalopram monotherapy but also fail to achieve a sufficient response after up to 3 subsequent levels of switching or adjunctive treatment interventions (Rush et al., 2006; Trivedi et al., 2006).

As relapse rates are high in patients with MDD who require multiple lines of treatment (Rush et al., 2006), there is a need to develop effective early treatment strategies for patients with inadequate response to treatment in order to increase the quality of life of these patients, improve clinical benefits, and, ultimately, aid recovery and restoration of euthymia (Connolly and Thase, 2011; Fava and Bech, 2015). A recent report has suggested that clinicians could target residual symptoms or treatment resistance by considering the mechanism of action of their treatments (Thase and Schwartz, 2015). Due to their broad receptor-binding profiles, atypical antipsychotics are considered a rational treatment choice as adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for the treatment of MDD, and there is a large evidence base supporting the augmentation of ADT with an atypical antipsychotic (Papakostas, 2009). The antipsychotics aripiprazole and quetiapine are approved in the US and other countries for use as adjunctive therapy to ADTs in the treatment of adults with MDD. The clinical use of atypical antipsychotics can, however, be limited by associated adverse events (AEs) (Nelson and Papakostas, 2009; Citrome, 2010, 2013); for instance, akathisia is associated with aripiprazole treatment, and somnolence and sedation are associated with quetiapine treatment (Gao et al., 2011; Citrome, 2013).

The serotonin-dopamine activity modulator, brexpiprazole, has recently received FDA approval (July 2015) for use as adjunctive therapy to ADTs for the treatment of adults with MDD based on results from two pivotal studies (Thase et al., 2015a; Thase et al., 2015b). Brexpiprazole has a unique pharmacological profile, acting as a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors, and an antagonist at serotonin 5-HT2A and noradrenaline alpha1B/2C receptors, all at similar potencies (Maeda et al., 2014). Clinical data suggest relatively lower rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and hyperprolactinemia compared with full D2 antagonists and lower rates of akathisia compared with partial agonists with more pronounced agonistic properties (Thase et al., 2015a; Thase et al., 2015b).

The objectives of this exploratory study were to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and subjects’ subjective satisfaction of patients with MDD who were switched to brexpiprazole after having an inadequate response to their prior adjunctive or combination therapy.

Methods

This was a phase 3b, multicenter, open-label, flexible-dose, exploratory study conducted between December 9, 2013 and October 14, 2014 (NCT02012218).

Patients

Male and female outpatients aged 18 to 65 years were recruited at 28 sites in the US. Inclusion criteria for the study included: diagnosis of MDD with a current major depressive episode (≥8 weeks duration) as defined by DSM-IV-TR and assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and a psychiatric evaluation; inadequate response to ≥1 adjunctive treatments in the current major depressive episode (including a history of ≥1 additional failure [in current or prior episode] to adequate monotherapy ADT [deemed both adequate in dose and duration at the investigator’s judgement]); Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D17) total score (Hamilton, 1960) ≥18 at screening and baseline visits; currently receiving a stable dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with adjunctive or combination treatment for ≥6 weeks prior to screening (permitted selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; escitalopram 10–20 mg/d, fluoxetine 20–40 mg/d, paroxetine controlled release 25–50 mg/d, or sertraline 50–200 mg/d; permitted serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, duloxetine delayed release 40–60 mg/d or venlafaxine extended release 75–225 mg/d); and a potential to benefit from adjunctive treatment with brexpiprazole, according to investigator judgement. Patients were excluded if they had received electroconvulsive therapy for the current major depressive episode, had a current need for involuntary commitment, had been hospitalized for their major depressive episode within 4 weeks of screening, had occurrence of hallucinations or delusions during the current major depressive episode, had a current diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder, or, in the opinion of the investigator, were at serious risk of suicide.

The study was carried out in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and applicable local laws and regulatory requirements. The protocol was approved by independent ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Design

This study consisted of a screening period of ≤3 weeks. Patients discontinued their adjunctive or combination medication ≥5 days before the start of a 6-week treatment period, during which time they received treatment with open-label brexpiprazole as an adjunctive therapy to current ADT. Patients were assessed at weekly visits. No change from the ADT administered in the screening period was permitted during the treatment period. All patients were categorized according to their prior adjunctive or combination therapy as follows: ADT+atypical antipsychotic (ADT+aripiprazole or ADT+quetiapine); ADT+ADT (combination); ADT+bupropion; ADT+stimulant (modafinil, methylphenidate, or other psychostimulant). The first 2 weeks of the treatment period consisted of a titration period in which brexpiprazole was started at 0.5 mg/d for 1 week, titrated to 1 mg/d for week 2, and increased to 2 mg/d (target dose) at the start of week 3. Following the titration period, administration of a flexible daily dose (1–3 mg/d) of brexpiprazole was permitted. Following the treatment period, brexpiprazole treatment was discontinued and patients underwent a safety follow-up period of 30 (±2) days.

Assessments

Function and Efficacy

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change from baseline to week 6 in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score, which ranges in value from 0 to 60 (Montgomery and Åsberg, 1979).

Exploratory endpoints included the MADRS response rate (defined as ≥50% reduction in MADRS total score from baseline), MADRS remission rate (defined as ≥50% reduction in MADRS total score from baseline and MADRS total score ≤10), and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale score, each assessed at all trial visits during the open-label treatment phase. MADRS response or remission at any given study visit did not depend on whether response or remission was present at a subsequent visit. Changes from baseline to week 6 were also measured in CGI-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) scale score (Guy, 1976); HAM-D17 total score; Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) mean and domain scores (Sheehan et al., 1996); Massachusetts General Hospital–Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (MGH-CPFQ) (Fava et al., 2009); Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-version 11 (BIS-11) (Patton et al., 1995); Insomnia Severity Index (ISI); Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) total score (Johns, 1993); and subject satisfaction, as measured by the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-14) (Atkinson et al., 2004).

Safety and Tolerability

Safety and tolerability were assessed through AEs, clinical laboratory tests, vital signs, physical examinations, body weight, and ECGs. The criteria for potentially clinically relevant change in fasting metabolic parameters or prolactin were as follows: cholesterol, ≥240 mg/dL; glucose, ≥100 mg/dL; HDL cholesterol, females <50 mg/dL, males, <40 mg/dL; LDL cholesterol, ≥160 mg/dL; prolactin, >upper limit of normal; and triglycerides, ≥150 mg/dL. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the Adult Treatment Panel III criteria (National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, 2002). Suicidality was assessed at each weekly visit using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Mean changes from baseline in EPS were assessed using the Simpson Angus Scale total score (Simpson and Angus, 1970), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale total score (Guy, 1976), and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale global score (Barnes, 1989), which were all measured at baseline and week 6.

Statistical Analysis

The safety analysis set comprised all patients who had received at least one dose of brexpiprazole. The full analysis set (FAS) comprised all patients who had received at least one dose of brexpiprazole and who had a baseline assessment and at least one postbaseline MADRS assessment. All efficacy analyses were performed on the FAS. Statistical comparisons between baseline and week 6 assessments were based on 2-sided 0.05 significance levels.

The primary efficacy endpoint, change from baseline to week 6 in MADRS total score, was analyzed using a mixed model repeated measures analysis, with the visit and enrollment group as fixed effects and interaction terms of enrollment group by visit and baseline MADRS total score using observed case (OC) data. The model also included baseline MADRS total score and the interaction term of baseline MADRS total score by visit as covariates. Missing data were imputed using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach. A sensitivity analysis was analyzed using an ANCOVA model, with enrollment group as a factor and MADRS total score at baseline as a covariate based on LOCF data.

MADRS response and remission rates and CGI-I responders were analyzed using exact binomial 95% CI on both OC and LOCF data. Change in CGI-S score was analyzed using the same mixed model repeated-measures model as for the primary efficacy analysis. Changes in HAM-D17, SDS, MGH-CPFQ, ISI, ESS, TSQM-14, and BIS-11 scores were analyzed using ANCOVA on OC data. CGI-I and safety results were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Of 124 patients who were screened for eligibility, 61 (49.2%) were enrolled in the study and received treatment with adjunctive brexpiprazole. The safety analysis set comprised all 61 patients and the FAS 59 patients; 2 patients did not meet the criteria for the FAS due to being lost to follow-up after the baseline assessment. The numbers of patients who had received each type of prior adjunctive or combination ADT therapy were as follows: ADT+aripiprazole (augmentation), n = 12; ADT+quetiapine (augmentation), n = 11; ADT+ ADT (combination), n = 13; ADT+bupropion (combination), n = 19; ADT+stimulant (augmentation with modafinil, methylphenidate, or other psychostimulant), n = 6. A total of 51/61 patients (83.6%) completed the study. Patients were discontinued from the study drug due to withdrawal of consent (4/61, 6.6%), AEs (2/61, 3.3%), patient being lost to follow-up (2/61, 3.3%), patient meeting protocol-specified withdrawal criteria (1/61, 1.6%), and protocol deviation (1/61, 1.6%).

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. At baseline, patients had severe depression, indicated by a mean (SD) baseline MADRS score of 29.6 (5.0), mean (SD) CGI-S score of 4.4 (0.5), and mean (SD) duration of current episode of 14.9 (17.5) months. At week 6 the mean (SD) dose of brexpiprazole for all patients was 2.25 (0.74) mg. Summary statistics of doses of ADT at baseline are given in supplementary Table 1; screening values for HAM-D17 total score are given in supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| ADT+brexpiprazole 1–3 mg/d (N = 61) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45.6 (12.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 32.4 (7.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 43 (70.5) |

| Male | 18 (29.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 39 (63.9) |

| Black or African American | 19 (31.1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1.6) |

| Asian | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 1 (1.6) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Duration of current episode, months | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.9 (17.5) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 10.0 (3, 120) |

| Number of lifetime episodes | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.0) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 4.0 (1, 10) |

| MADRS total score, mean (SD)a | 29.6 (5.0) |

| HAM-D17 total score, mean (SD)a | 23.5 (3.3) |

| CGI-S total score, mean (SD)a | 4.4 (0.5) |

| SDS score, mean (SD)a | 6.3 (2.0) |

| Work/school | 5.2 (2.6) |

| Social life | 6.5 (2.1) |

| Family life/home responsibilities | 6.7 (2.3) |

| MGH-CPFQ total score, mean (SD)a | 29.3 (5.5) |

| ISI total score, mean (SD)a | 16.2 (6.2) |

| ESS total score, mean (SD)a | 10.1 (5.9) |

| BIS-11 total score, mean (SD)a | 72.6 (13.4) |

| TSQM-14, mean (SD)a | |

| Effectiveness score | 37.0 (19.1) |

| Side effects score | 83.8 (27.4) |

| Convenience score | 78.7 (15.9) |

| Global satisfaction score | 47.3 (20.8) |

Abbreviations: ADT, antidepressant treatment; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-version 11; BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression- Severity; FAS, full analysis set; HAM-D17, Hamilton Depression Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MGH-CPFQ, Massachusetts General Hospital–Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; TSQM-14, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication – 14 item.

aBased on FAS (n = 59).

Efficacy

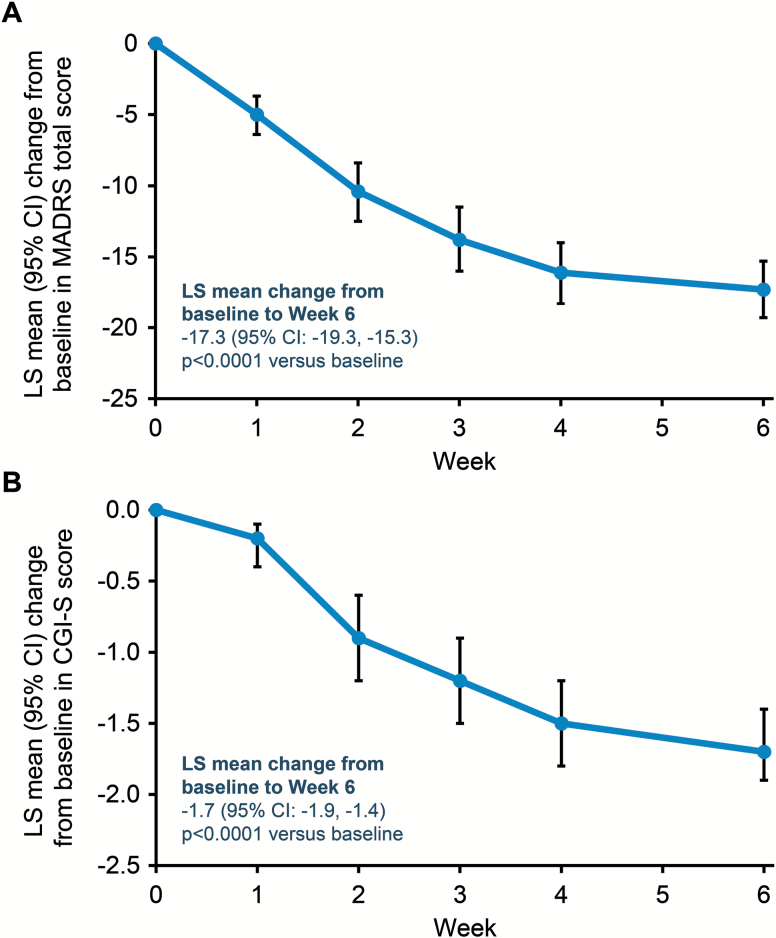

Improvements in depressive symptoms were observed, as evidenced by a reduction from baseline to week 6 in least squares (LS) mean change (95% CI) in MADRS total score of −17.3 (−19.3, −15.3), P < .0001 (Figure 1A) from a baseline score of 29.6. Results from the sensitivity analysis confirmed this finding. Significant reductions were seen in MADRS total score irrespective of prior adjunctive or combination therapy (all P < .0001): changes ranged from an LS mean change of −12.8 from a baseline score of 30 in the group switched from ADT+aripiprazole, to an LS mean change of −19.5 from a baseline score of 31.2 in the group switched from ADT+adjunctive ADT (supplementary Table 3). A significant LS mean reduction from baseline to week 6 was also observed for CGI-S score (Figure 1B). Reductions in MADRS and CGI-S scores over baseline were seen from week 1. These results were supported by an LS mean (95% CI) change from baseline to week 6 in HAM-D17 total score of −13.8 (−15.4, −12.2); P < .0001 and mean (SD) CGI-I score at week 6 of 1.8 (0.9). A similar pattern of significant changes in CGI-S and HAM-D17 total scores was also seen for each type of prior adjunctive or combination therapy (supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Changes in depressive symptoms. (A) Mean change from baseline in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score. (B) Mean change from baseline in Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score. All patients received ADT+brexpiprazole 1 to 3 mg/d switched from previous adjunctive or combination treatment; primary antidepressant treatment (ADT) kept constant. Analyzed using mixed model repeated measures on observed cases (OC) data; P value relative to baseline. LS, least squares.

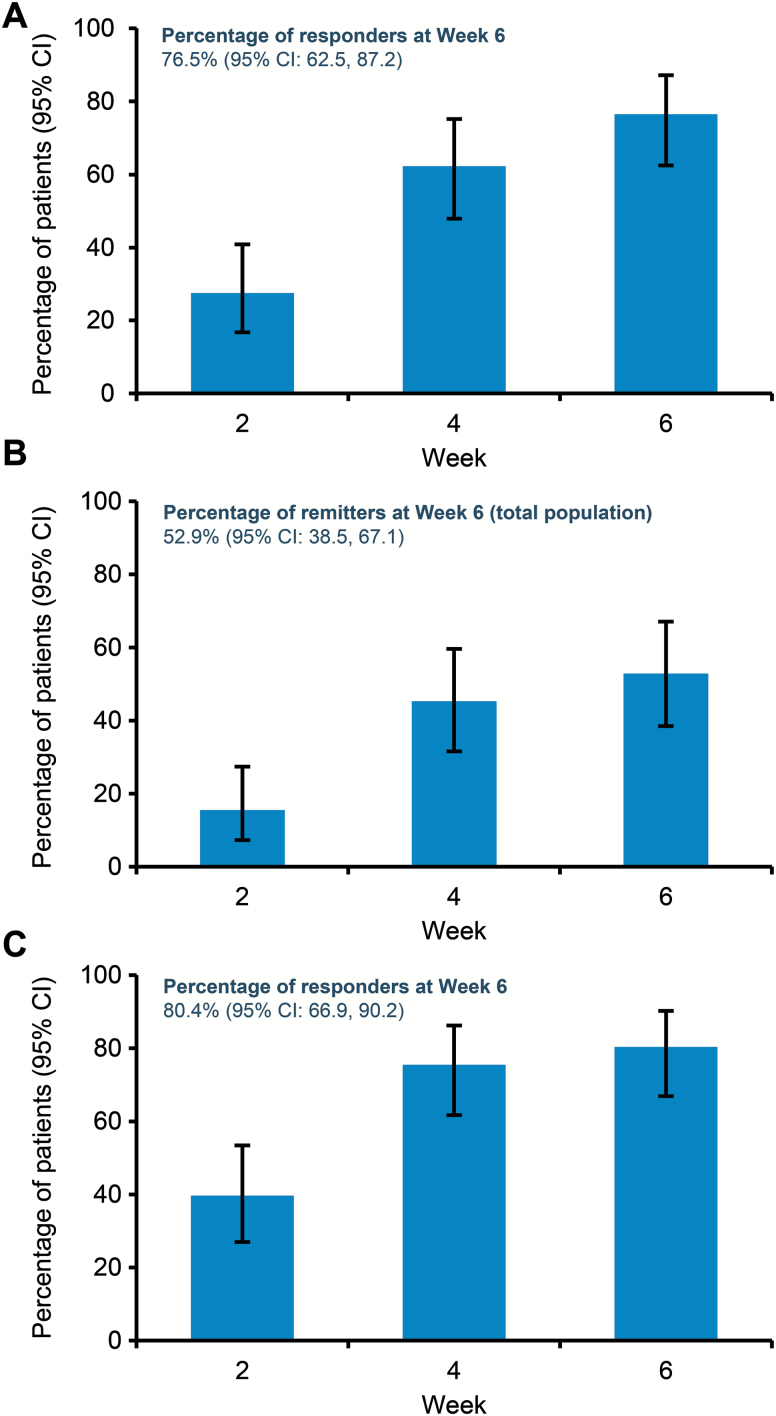

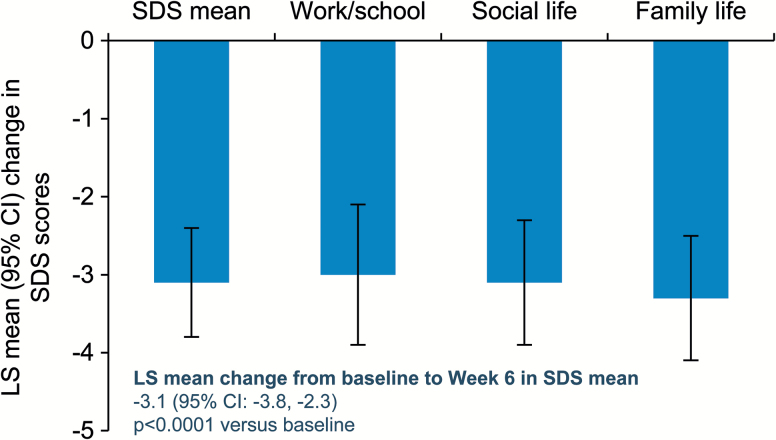

The percentages of patients with MADRS response, MADRS remission, and CGI-I response increased at each study visit (Figure 2). At week 6, MADRS response rate was 76.5%, MADRS remission rate was 52.9%, and CGI-I response rate was 80.4%. The mean changes from baseline to week 6 in the self-reported SDS scale were substantial (−3.1) and were supported by similar improvements in all 3 SDS domains (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Response and remission rates for Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and response rates for Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I). (A) Percentage of patients with MADRS response, defined as a ≥50% reduction from baseline in total score. (B) Percentage of patients with MADRS remission, defined as a total score decrease ≥50% from baseline and ≤10. (C) CGI-I response rates, defined as a score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved). All patients received ADT+brexpiprazole 1–3 mg/d switched from previous adjunctive or combination treatment; primary antidepressant treatment (ADT) kept constant. Analyzed by exact binomial 95% CI on observed cases (OC) data.

Figure 3.

Changes from baseline in Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) mean and domain scores. Analyzed using ANCOVA on observed cases (OC) data. LS, least squares.

Improvements were also observed in patient-rated outcomes of cognitive and physical functioning (as assessed by MGH-CPFQ, a measure of cognition and physical function defined by motivation, alertness, and energy), sleep [ISI score], and impulsivity [BIS-11] (Table 2). Mean changes from baseline in ESS showed small numerical improvements, indicating that daytime sleepiness did not worsen compared with previous adjunctive or combination treatment. Changes in TSQM-14 indicated improvements in treatment satisfaction in the effectiveness, convenience, and global satisfaction domains and no worsening in the side effects domain (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of Changes in Patient-Reported Outcomes of Cognitive and Physical Functioning, Sleep, and Impulsivity

| ADT+brexpiprazole 1–3 mg/d (N = 59) | |

|---|---|

| Cognitive and physical functioning | |

| MGH-CPFQ scorea | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −9.2 (1.1) |

| 95% CI | −11.5, −6.9 |

| P value | <.0001 |

| Sleep | |

| ISI scorea | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −5.7 (0.9) |

| 95% CI | −7.5, −3.9 |

| P value | <.0001 |

| ESS scorea | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −0.6 (0.7) |

| 95% CI | −2.0, 0.7 |

| P value | .3518 |

| Impulsivity | |

| BIS-11 total scorea | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −4.1 (1.2) |

| 95% CI | −6.4, −1.8 |

| P value | .0008 |

Abbreviations: ADT, antidepressant treatment; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-version 11; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; LS, least squares; MGH-CPFQ, Massachusetts General Hospital–Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire; OC, observed cases.

aAnalyzed using ANCOVA on OC data; P value relative to baseline.

Table 3.

Summary of Changes in Treatment Satisfaction

| ADT+brexpiprazole 1–3 mg/d (N = 59) | |

|---|---|

| TSQM-14 effectiveness domaina | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 28.7 (3.6) |

| 95% CI | 21.4, 35.9 |

| P value | <.0001 |

| TSQM-14 side effects domaina | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −6.4 (4.9) |

| 95% CI | −16.3, 3.4 |

| P value | .1963 |

| TSQM-14 convenience domaina | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 7.4 (2.1) |

| 95% CI | 3.3, 11.5 |

| P value | .0007 |

| TSQM-14 global satisfaction domaina | |

| n | 51 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 17.7 (4.2) |

| 95% CI | 9.3, 26.2 |

| P value | .0001 |

Abbreviations: ADT, antidepressant treatment; LS, least squares; OC, observed cases; TSQM-14, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication – 14 item.

aAnalyzed using ANCOVA on OC data; P value relative to baseline.

Safety and Tolerability

A total of 41/61 patients (67.2%) reported ≥1 treatment- emergent AE (TEAE). The most commonly reported TEAE was fatigue (Table 4). A total of 2/61 (3.3%) subjects withdrew because of TEAEs of moderate cognitive disorder (previously treated with combination bupropion and base ADT sertraline) and severe extrapyramidal disorder (previously treated with adjunctive aripiprazole and base ADT venlafaxine). Neither of these AEs was serious but were considered by the investigator to be related to study drug; both resolved within 1 week of discontinuing the study drug. No patients died during the study. One single, serious TEAE of rhabdomyolysis was reported; this event occurred in a 56-year-old white male, currently treated with fluoxetine and switched from quetiapine to brexpiprazole, subsequent to a fall resulting in mild head injury. None of these events was considered by the investigator to be related to study treatment. At the time of these events, the patient had been receiving adjunctive brexpiprazole for 42 days and had been on a 3-mg/d dose for 20 days; no changes to therapy were made following these events. Four days later, at the last study visit, laboratory tests revealed markedly elevated creatine phosphokinase, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase, aspartate amino transferase, lactate, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine. The rhabdomyolysis resolved following administration of i.v. 0.9% saline, with all laboratory parameters returning to within the reference range after 15 days. The rhabdomyolysis was not considered to be related to either brexpiprazole or fluoxetine.

Table 4.

Summary of Adverse Events

| ADT+brexpiprazole 1–3 mg/d (N = 61) | |

|---|---|

| At least one TEAE, n (%) | 41 (67.2) |

| At least one SAE, n (%) | 1 (1.6) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation, n (%) | 2 (3.3) |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients, n (%) | |

| Fatigue | 9 (14.8) |

| Headache | 5 (8.2) |

| Akathisia | 5 (8.2) |

| Restlessness | 5 (8.2) |

| Dry mouth | 5 (8.2) |

| Increased appetite | 5 (8.2) |

| Somnolence | 4 (6.6) |

| Insomnia | 4 (6.6) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (6.6) |

| Other relevant TEAEs, n (%) | |

| Anxiety | 2 (3.3) |

| Sedation | 2 (3.3) |

Abbreviations: ADT, antidepressant treatment; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

EPS-related TEAEs were reported by a total of 7/61 patients (11.5%), including: akathisia (n = 5), extrapyramidal disorder (n = 1, patient discontinued study), and muscle rigidity (n = 1). No notable changes were observed in the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale EPS rating scales (LS mean [standard error; SE] changes from baseline to week 6; −0.1 [0.0] P = not assessed and −0.1 [0.08] P = .2459, respectively). The LS mean (SE) change from baseline to week 6 in Simpson Angus Scale was −0.2 (0.06), P = .0020.

The mean (SD) change from baseline to week 6 in body weight was 1.34 (3.24) kg. No patients had a clinically relevant (≥7% increase) weight gain. One patient (1.7%) had a clinically relevant weight decrease (≥7%); this patient had previously received treatment with ADT+adjunctive ADT.

With respect to clinical laboratory test results and metabolic parameters, no notable changes were observed during the study; changes from baseline to week 6 in prolactin and standard fasting metabolic parameters are presented in supplementary Table 4. Incidences of potentially clinically relevant test results (according to predefined criteria) at any time during the study were as follows: fasting cholesterol, 7/51 (13.7%); fasting glucose, 10/51 (19.6%); fasting HDL, females 9/38 (23.7%), males 4/13 (30.8%); fasting LDL, 6/49 (12.2%); prolactin, 2/57 (3.5%); and fasting triglycerides, 19/51 (37.3%). No patients met the criteria for metabolic syndrome.

During the 6-week treatment period, there were no suicidal behaviors as indicated by the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. There were no incidences of TEAEs related to suicidality throughout the study.

Discussion

In this exploratory, open-label study, improvements in depression, overall functioning, cognitive function, energy/alertness, and patient satisfaction were evaluated following a switch to adjunctive treatment with brexpiprazole in patients with MDD who had an inadequate response to previous adjunctive or combination therapy.

Efficacy benefits on depressive symptoms were observed in patients who switched from previous adjunctive therapy or combination ADT to adjunctive brexpiprazole, as evidenced by improvements in MADRS total score, HAM-D17 total score, CGI-S, and CGI-I scores. The efficacy benefits observed here support efficacy data obtained from pivotal phase 3 studies of adjunctive brexpiprazole (Thase et al., 2015a; Thase et al., 2015b). Additionally, in this study, 76.5% of patients were MADRS responders and 52.9% were MADRS remitters at week 6. The declining likelihood of remission, demonstrated with each treatment level in STAR*D, highlights the need for effective switching or augmentation treatment strategies in the event that patients do not adequately respond to their ADT (Rush et al., 2006). The efficacy benefits observed here at week 6 suggest that a switch to adjunctive brexpiprazole may be an efficacious treatment strategy for patients who have experienced inadequate response to their preceding adjunctive or combination therapies.

Many patients with MDD experience impairments to functioning and quality of life, and patients with MDD who experience inadequate response (partial or no response) to their ADT are more likely to experience low employment prospects or loss in work productivity (Knoth et al., 2010; Kessler, 2012). As improvements in patient functioning can be delayed behind improvements in depressive symptoms (Nierenberg and DeCecco, 2001), improving the functioning of patients with MDD, alongside improvements in depressive symptoms, would benefit patients through preservation of social functioning and improving quality of life. A recent study has demonstrated that changes in cognition (measured with the CPFQ) were highly predictive of changes in functioning in patients with depression receiving ADT (Rothschild et al., 2014). In the present study, the improvements observed in cognition with the CPFQ were robust and consistent with the improvements in functioning detected with the SDS. These findings are particularly meaningful because they evaluate the impact of treatment beyond clinical symptoms to consider outcomes that are important to patients and will facilitate their return to normal functioning (e.g., workplace productivity, interactions with family/friends, and social integration) (Papakostas and Culpepper, 2015).

Sleep disturbances are frequent in MDD and need to be successfully treated in order to achieve full clinical remission. If present as a residual symptom, sleep disturbances may be predictive of a relapse (Mendlewicz, 2009). Previous studies have shown improvements in sleep disturbances, sleep, and daytime alertness (as measured by polysomnography, the ISI scale, and ESS scale, respectively) in patients with MDD who were treated with adjunctive brexpiprazole (A. Krystal, unpublished observations). Although improvements of sleep were observed, the small improvements in ESS total score indicated that patients’ daytime alertness was no worse than it was on prior adjunctive or combination therapy. In addition, wakefulness/alertness and energy are part of the physical functioning measured on the CPFQ (Fava et al., 2009; Baer et al., 2014), which improved with brexpiprazole treatment.

In patients with MDD, impulsivity has been identified as a potentially reliable suicide risk marker, and impulsive behaviors are exhibited more commonly among individuals with MDD featuring anxiety symptoms or anxiety comorbidities (Perroud et al., 2011; Bellani et al., 2012). As such, findings from our study showing improvements in BIS-11 provide additional reassurance that brexpiprazole adjunctive therapy may prove to be an effective therapeutic option in patients with MDD and an inadequate response to prior adjunctive or combination therapy.

Furthermore, patient satisfaction findings were consistent with symptom improvements that, coupled with the observed cognitive and functional improvements, suggest patients switching to adjunctive brexpiprazole may also achieve improvements to their quality of life.

The range of adjunctive treatments from which patients could be switched reflects current practice and guidelines, not necessarily FDA-approved adjunctive therapies. In fact, bupropion was shown to be ineffective as adjunctive to escitalopram in the COMED study (Rush et al., 2011), and little evidence exists to support the clinical efficacy of augmentation with buspirone (Fleurence et al., 2009). Additionally, recent results have demonstrated that an adjunctive stimulant, lisdexamfetamine, was not superior to adjunctive placebo for improvements in MADRS total score in studies of patients with depression (Trivedi et al., 2013; McElroy et al., 2015). As well as brexpiprazole, the FDA has only approved aripiprazole and quetiapine for the adjunctive treatment of MDD, both of which have demonstrated good efficacy at improving symptoms (Nelson and Papakostas, 2009; Papakostas, 2009; Thase et al., 2015a; Thase et al., 2015b). Barriers to use of atypical antipsychotics as adjunctive therapy to ADT include concern about EPS-related side effects, weight gain, and metabolic changes, as well as unwanted sedation or activation, which occur to varying degrees depending on choice of atypical, despite good evidence for their efficacy (Goodwin et al., 2009; Connolly and Thase, 2011).

The overall incidence of AEs observed in patients who switched to adjunctive brexpiprazole was in line with what was observed in the 2 pivotal phase 3 studies for brexpiprazole (Thase et al., 2015a; Thase et al., 2015b). The changes observed in the TSMQ-14 side effects domain suggest that patients notice that side effects of brexpiprazole are different, but not worse than those experienced on previous adjunctive or combination therapy.

Overall, the efficacy and safety profile of adjunctive brexpiprazole suggests that switching to adjunctive brexpiprazole may be an effective treatment strategy for patients with MDD who have experienced inadequate response to their prior adjunctive or combination ADT therapy. Limitations to this study include the small number of patients, lack of an active comparator, and the open-label design. The short washout period for prior adjunctive or combination therapy may have resulted in possible synergi stic effects between prior therapy and brexpiprazole. Resolution of side effects associated with discontinued prior adjunctive or combination therapy may have contributed to the improvement seen in exploratory outcomes. Future placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm the preliminary observations reported here.

Conclusions

The results presented here are supportive of the efficacy and safety of a switch from commonly utilized adjunctive or combination agents to adjunctive brexpiprazole treatment in patients with MDD who have had a previous inadequate response to a previous adjunctive or combination therapy to an ADT. Results here are also supportive of improvements to functional outcomes in patients switching to adjunctive brexpiprazole, providing additional aspects to the treatment of MDD.

Funding

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark).

Statement of Interest

Maurizio Fava is a consultant to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S. Pamela Perry and Ross A. Baker are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization (Princeton, NJ). Takao Okame and Yuki Matsushima are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Commercialization, Inc (Tokyo, Japan). Emmanuelle Weiller is an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark). For a complete list of lifetime disclosures for Dr. Maurizio Fava, please see https://protect-eu.mimecast.com/s/zw3iBQNzRtw?domain=mghcme.org, http://mghcme.org/faculty/faculty-detail/maurizio_fava.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ruth Steer, PhD (QXV Communications [an Ashfield business, part of UDG healthcare plc,] Macclesfield, UK) provided writing support that was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Commercialization, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) and H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark).

References

- Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR. (2004) Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer L, Ball S, Sparks J, Raskin J, Dube S, Ferguson M, Fava M. (2014) Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ). Ann Clin Psychiatry 26:270–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR. (1989) A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellani M, Hatch JP, Nicoletti MA, Ertola AE, Zunta-Soares G, Swann AC, Brambilla P, Soares JC. (2012) Does anxiety increase impulsivity in patients with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder? J Psychiatr Res 46:616–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L. (2010) Adjunctive aripiprazole, olanzapine, or quetiapine for major depressive disorder: an analysis of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Postgrad Med 122:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L. (2013) A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs 27:879–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly KR, Thase ME. (2011) If at first you don’t succeed: a review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategies. Drugs 71:43–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Bech P. (2015) The concept of euthymia. Psychother Psychosom 85:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M. (2001) Augmentation and combination strategies in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 62:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M. (2003) Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 53:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ. (2006) Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom 75:139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Iosifescu DV, Pedrelli P, Baer L. (2009) Reliability and validity of the Massachusetts general hospital cognitive and physical functioning questionnaire. Psychother Psychosom 78:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleurence R, Williamson R, Jing Y, Kim E, Tran QV, Pikalov AS, Thase ME. (2009) A systematic review of augmentation strategies for patients with major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 42:57–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Kemp DE, Fein E, Wang Z, Fang Y, Ganocy SJ, Calabrese JR. (2011) Number needed to treat to harm for discontinuation due to adverse events in the treatment of bipolar depression, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder with atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 72:1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin G, Fleischhacker W, Arango C, Baumann P, Davidson M, de Hert M, Falkai P, Kapur S, Leucht S, Licht R, Naber D, O’Keane V, Papakostas G, Vieta E, Zohar J. (2009) Advantages and disadvantages of combination treatment with antipsychotics ECNP Consensus Meeting, March 2008, Nice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19:520–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. (1976) ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology (revised). In: Hamilton anxiety scale (Hamilton M, ed), pp 193–198. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM) 76–338, Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960) A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MW. (1993) Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest 103:30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. (2012) The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 35:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, Tran QV. (2010) Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care 16:e188–e196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Sugino H, Akazawa H, Amada N, Shimada J, Futamura T, Yamashita H, Ito N, McQuade RD, Mork A, Pehrson AL, Hentzer M, Nielsen V, Bundgaard C, Arnt J, Stensbol TB, Kikuchi T. (2014) Brexpiprazole I: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel serotonin-dopamine activity modulator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Martens BE, Mori N, Blom TJ, Casuto LS, Hawkins JM, Keck PE., Jr (2015) Adjunctive lisdexamfetamine in bipolar depression: a preliminary randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 30:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlewicz J. (2009) Sleep disturbances: core symptoms of major depressive disorder rather than associated or comorbid disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry 10:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. (1979) A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (2002) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. (2009) Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 166:980–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, DeCecco LM. (2001) Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry 62:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI. (2009) Managing partial response or nonresponse: switching, augmentation, and combination strategies for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 70(Suppl 6):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI, Culpepper L. (2015) Understanding and managing Cognition in the Depressed Patient. J Clin Psychiatry 76:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. (1995) Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51:768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Baud P, Mouthon D, Courtet P, Malafosse A. (2011) Impulsivity, aggression and suicidal behavior in unipolar and bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord 134:112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild AJ, Raskin J, Wang CN, Marangell LB, Fava M. (2014) The relationship between change in apathy and changes in cognition and functional outcomes in currently non-depressed SSRI-treated patients with major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 55:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackeim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M. (2006) Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 163:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Kurian BT, Warden D, Morris DW, Luther JF, Husain MM, Cook IA, Shelton RC, Lesser IM, Kornstein SG, Wisniewski SR. (2011) Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): acute and long-term outcomes of a single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry 168:689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. (1996) The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 11:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM, Angus JW. (1970) A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Schwartz TL. (2015) Choosing medications for treatment-resistant depression based on mechanism of action. J Clin Psychiatry 76:720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, Hobart M, Zhang P, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Eriksson H. (2015. a) Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 76:1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, Hobart M, Augustine C, Zhang P, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Nyilas M, Sanchez R, Eriksson H. (2015. b) Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 76:1224–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, on behalf of the Star*D Study Team (2006) Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 163:28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Cutler AJ, Richards C, Lasser R, Geibel BB, Gao J, Sambunaris A, Patkar AA. (2013) A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate as augmentation therapy in adults with residual symptoms of major depressive disorder after treatment with escitalopram. J Clin Psychiatry 74:802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.