Abstract

Background:

Brexpiprazole has previously demonstrated efficacy in acute schizophrenia trials. The objective of this trial was to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of maintenance treatment with brexpiprazole in adults with schizophrenia.

Methods:

Patients with an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms were converted to brexpiprazole (1–4mg/d) over 1 to 4 weeks and entered a single-blind stabilization phase. Those patients who met stability criteria for 12 weeks were randomized 1:1 to double-blind maintenance treatment with either brexpiprazole (at their stabilization dose) or placebo for up to 52 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was the time from randomization to impending relapse. Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

Results:

A total of 524 patients were enrolled, 202 of whom were stabilized on brexpiprazole and randomized to brexpiprazole (n=97) or placebo (n=105). Efficacy was demonstrated at a prespecified interim analysis (conducted after 45 events), and so the trial was terminated early. The final analysis showed that time to impending relapse was statistically significantly delayed with brexpiprazole treatment compared with placebo (P<.0001, log-rank test). The hazard ratio for the final analysis was 0.292 (95% confidence interval: 0.156, 0.548); mean dose at last visit, 3.6mg. The proportion of patients meeting the criteria for impending relapse was 13.5% with brexpiprazole and 38.5% with placebo (P<.0001). During the maintenance phase, the incidence of adverse events was comparable to placebo.

Conclusions:

or patients with schizophrenia already stabilized on brexpiprazole, maintenance treatment with brexpiprazole was efficacious, with a favorable safety profile.

Keywords: brexpiprazole, maintenance, relapse, schizophrenia, stabilization

Significance Statement

Brexpiprazole is a new antipsychotic that has been approved in the United States for the treatment of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder (adjunct to antidepressants). Approval in schizophrenia was based on two acute trials in which brexpiprazole was well tolerated and showed a clinically meaningful improvement vs placebo. The present paper complements this short-term evidence by presenting results from the first long-term, controlled, clinical trial of brexpiprazole as a maintenance treatment for schizophrenia. Brexpiprazole was found to be an efficacious maintenance therapy over the course of 1 year, reducing the risk of impending relapse by 71% vs placebo, and with an incidence of adverse events that was comparable to placebo. Furthermore, the trial assessed changes in social functioning and cognitive ability with brexpiprazole treatment. Overall, this paper suggests that brexpiprazole is a beneficial maintenance treatment for patients with schizophrenia who are stabilized on brexpiprazole.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder with a median lifetime morbid risk of about 7 individuals per 1000 (McGrath et al., 2008). Following successful treatment of an acute episode of schizophrenia, treatment guidelines state that prevention of relapse is an important long-term treatment goal (Lehman et al., 2004; Hasan et al., 2013). Relapse has significant psychosocial repercussions for patients, including impaired functioning, disrupted social relationships, and disrupted employment status (Kane, 2007). Relapse is associated with increased costs for inpatient care and outpatient support (Ascher-Svanum et al., 2010), and may also be associated with a period of disease progression, although evidence for this is inconclusive (Emsley et al., 2013). Maintenance treatment with antipsychotics substantially reduces the risk of relapse in patients with schizophrenia (Leucht et al., 2012; Sampson et al., 2013). However, despite the evidence, many patients do not receive maintenance therapy after successful treatment of an acute episode. Several explanations have been cited for this treatment gap, including that patients are not convinced of the need for continued treatment and that antipsychotics are associated with a considerable side-effect burden (Emsley et al., 2013).

Brexpiprazole acts as a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors and an antagonist at serotonin 5-HT2A and noradrenaline α1B and α2C receptors (Maeda et al., 2014). Brexpiprazole has subnanomolar and almost equal binding affinities for D2, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, α1B, and α2C receptors (inhibition constants [Ki] in the range of 0.12–0.59nM), and therefore brexpiprazole is likely to show similar occupancy of these receptors in vivo (Maeda et al., 2014). In two 6-week phase III schizophrenia trials, brexpiprazole was well tolerated and showed a clinically meaningful improvement vs placebo at the 4-mg/d dose and also at the 2-mg/d dose in one trial (Kane et al., 2015; Correll et al., 2015). Brexpiprazole was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of schizophrenia, and the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder, in July 2015.

Short-term evidence of efficacy and safety needs to be complemented by longer-term evidence. The objective of this trial was to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of maintenance treatment with brexpiprazole compared with placebo in adults with schizophrenia.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Patients were recruited at 49 sites across 7 countries: the United States including Puerto Rico (36% of randomized patients), Ukraine (21%), Serbia (16%), Malaysia (10%), Romania (8%), Colombia (6%), and Turkey (2%). The trial was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guideline and local regulatory requirements, and the trial protocol was approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee for each investigational site. All patients provided written informed consent.

The trial included male and female inpatients and outpatients aged 18 to 65 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia for at least 3 years as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR®; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Patients must have been experiencing an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms at screening, as demonstrated by a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987) total score of >80. Patients must have shown response to antipsychotic treatment (other than clozapine) in the previous year, be currently treated with oral or depot antipsychotics (other than clozapine) or have a recent lapse in antipsychotic treatment, and have a history of relapse and/or symptom exacerbation in the absence of antipsychotic treatment. Exclusion criteria included a DSM-IV-TR® Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia, acute depressive symptoms in the previous 30 days requiring antidepressant therapy, antipsychotic-resistant or refractory schizophrenia, a significant risk of violent behavior or suicide, meeting DSM-IV-TR® criteria for substance abuse or dependence in the previous 180 days, or requiring prohibited concomitant therapy during the trial.

The trial comprised a screening phase, a phase for conversion from other antipsychotics to oral brexpiprazole (and washout of prohibited concomitant medications), a single-blind treatment phase to stabilize patients on oral brexpiprazole, a double-blind maintenance treatment phase, and a safety follow-up phase (supplementary Figure 1). Eligible patients, as determined during screening, entered either the open-label conversion phase or the single-blind stabilization phase. Patients entered the conversion phase (weekly visits) if they were currently receiving oral or long-acting injectable antipsychotic treatment, and/or if they required washout of prohibited concomitant medications. The purpose of the conversion phase was to cross-titrate the patient’s current antipsychotic treatment(s) to brexpiprazole monotherapy over a period of 1 to 4 weeks and to allow washout of prohibited medications. Brexpiprazole was initiated at 1mg/d, and the dose was adjusted within the range of 1 to 4mg/d over the cross-titration period according to the investigator’s judgment. Patients completing the conversion phase and those who did not require washout of prohibited concomitant medications (supplementary Figure 1) entered a 12- to 36-week stabilization phase. In this phase (weekly visits for 4 weeks, 2 weekly thereafter), patients were titrated to a dose of brexpiprazole (1–4mg/d) that would maintain stability of psychotic symptoms while minimizing tolerability issues. Stability was defined as meeting all of the following criteria for 12 consecutive weeks (one excursion was permitted prior to last visit): (1) outpatient status; (2) PANSS total score of ≤70; (3) score of ≤4 on each of the following PANSS items: conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content; (4) Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness (CGI-S; Guy, 1976) score of ≤4 (moderately ill); (5) no current suicidal behavior as assessed by the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2011); and (6) no violent or aggressive behavior resulting in injury or property damage.

In addition, the dose of brexpiprazole must have been stable for at least the last 4 weeks of the stability period. Patients not achieving 12 weeks of stability after 36 weeks of treatment were discontinued. In the 52-week maintenance phase (2 weekly visits for 8 weeks, 4 weekly thereafter), patients who met the stability criteria were randomized 1:1 to double-blind, parallel-arm treatment with either their stabilization dose of brexpiprazole or placebo. An interactive voice/web response system was used to assign blocks of randomization numbers to trial centers and individual numbers to patients according to a computer-generated randomization code provided by the sponsor. Brexpiprazole and placebo were supplied as tablets, identical in appearance, in weekly blister cards. Patients were not informed of dose adjustments and should not have been aware of the transition between phases. Except in cases of emergency, patients and trial personnel remained blinded to the identity of the treatment assignments until every patient had completed trial treatment.

Safety follow-up comprised telephone contact or a clinic visit 30 (+2) days after the last dose. There were no protocol amendments.

Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint of this trial was the time from randomization to exacerbation of psychotic symptoms/impending relapse (referred to hereafter as impending relapse) in the double-blind maintenance phase, defined as meeting any of the following 4 criteria:

Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement (CGI-I; Guy, 1976) score of ≥5 (minimally worse) and an increase on any of the following PANSS items: conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content (a) to a score of >4 with an absolute increase of ≥2 on that specific item since randomization, or (b) to a score of >4 with an absolute increase of ≥4 on the combined 4 PANSS items since randomization.

hospitalization due to worsening of psychotic symptoms

suicidal behavior as assessed by the C-SSRS

violent or aggressive behavior resulting in injury or property damage.

These criteria for impending relapse have been used previously in clinical trials of long-acting injectable aripiprazole (Fleischhacker et al., 2014; Ishigooka et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2012), and comparable criteria have been used for over a decade (Csernansky et al., 2002). The appearance of any of the signs of impending relapse at any visit resulted in withdrawal from the trial.

The key secondary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients meeting impending relapse criteria in the double-blind maintenance phase. Other secondary efficacy outcomes were the proportion of patients still meeting stability criteria at their last (post-baseline) visit in the double-blind maintenance phase, mean change in PANSS total, positive subscale, and negative subscale scores, mean change in CGI-S score, mean CGI-I score, mean change in Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale score, mean change in Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale score, time to discontinuation due to any reason, mean change in PANSS excited component score, mean change in PANSS Marder factor scores, and mean change in Cogstate computerized cognitive test battery scores (individual tasks and composite score). The PSP and GAF are clinician-rated scales that assess a patient’s functioning on a scale from 1 (worst) to 100 (best); the PSP measures socially useful activities (including work and study), personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing and aggressive behaviors; the GAF measures psychological, social, and occupational/school functioning (Morosini et al., 2000; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The PANSS is commonly split into positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscales; in addition, retrospective factor analysis produced 5 domains referred to as Marder factors (positive symptoms [8 items], negative symptoms [7 items], disorganized thought [7 items], uncontrolled hostility/excitement [4 items], and anxiety/depression [4 items]); (Marder et al., 1997). Furthermore, the PANSS excited component assesses agitation based on 5 PANSS items (excitement, hostility, tension, uncooperativeness, and poor impulse control); (Montoya et al., 2011). The Cogstate battery comprises computerized versions of standard cognitive tasks, 4 of which were used in the present study: detection task (processing speed), identification task (attention/vigilance), 1-card learning task (visual learning), and Groton maze learning task (reasoning and problem solving) (Pietrzak et al., 2009; Maruff et al., 2009).

Safety was assessed by spontaneous reporting of adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory tests, physical examination, vital signs, body weight, and electrocardiograms. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) were formally assessed using the Simpson–Angus Scale (Simpson and Angus, 1970), Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (Barnes, 1989), and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (Guy, 1976). Suicidality was assessed using the C-SSRS.

Statistical Analyses

With an assumption that 45% of patients who received placebo and 25% of patients who received brexpiprazole would relapse in 6 months, a hazard ratio of 0.4812 (brexpiprazole vs placebo) was derived. Thus, 90 relapse events were needed to reach 93% power to test the primary hypothesis at a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05. Two interim analyses were planned for assessment of efficacy (at approximately 50% and 75% of events of impending relapse [45 and 68 events, respectively]), so that the trial could be terminated once the primary objective was met in order to minimize exposure to placebo in the maintenance phase. An interim analysis review committee was formed for the independent review of unblinded efficacy data.

The enrolled population comprised all patients who signed an informed consent form and entered the conversion phase or the stabilization phase. Safety and efficacy samples were defined for both the stabilization phase and the maintenance phase. The safety samples comprised all patients who received at least one dose of trial medication in the corresponding phase. The efficacy samples comprised all patients in the corresponding safety samples who had at least one post-baseline efficacy evaluation in that phase.

The primary efficacy analysis was a log-rank test at the 0.05 significance level (2-sided) comparing time to impending relapse in the brexpiprazole group vs the placebo group in the maintenance phase efficacy sample. O’Brien–Fleming boundaries were used to maintain an overall significance level of 0.05 (2-sided) for the planned interim analyses at 45 and 68 events and the final analysis at 90 events; the corresponding 2-sided alpha levels were 0.003051, 0.018325, and 0.044005, respectively. Rate of impending relapse was plotted on a Kaplan–Meier curve; a hazard ratio (brexpiprazole vs placebo) and 95% CI were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as term. The key secondary efficacy analysis was a chi-squared test comparing the percentage of patients in each group meeting impending relapse criteria in the maintenance phase efficacy sample. A hierarchical testing procedure was employed to preserve the overall type I error rate at 0.05: the key secondary endpoint was tested at the 0.05 level only if the primary endpoint was statistically significant at an overall nominal alpha level of 0.05. Other secondary efficacy analyses were conducted in the stabilization phase, with descriptive statistics by visit, and in the maintenance phase, with mixed-effect model repeated measures (MMRM) analyses using observed data, and last observation carried forward (LOCF) sensitivity analyses using an ANCOVA model. In the maintenance phase, CGI-I score was analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel method with LOCF data. The change in Cogstate cognitive test battery composite score was calculated from the average of z-scores for each individual task. In the maintenance phase, an ANCOVA model was used, and Cohen’s d was calculated to assess the magnitude of the effect size.

All safety analyses used descriptive statistics; formal EPS rating scales were also evaluated using ANCOVA.

Results

Results of the first interim analysis were positive, and the trial was terminated because the primary endpoint of a significant delay in time to impending relapse for patients randomized to brexpiprazole compared with placebo had been achieved. The trial was initiated on 24 October 2012 and completed on 12 February 2015.

Patient Disposition and Characteristics

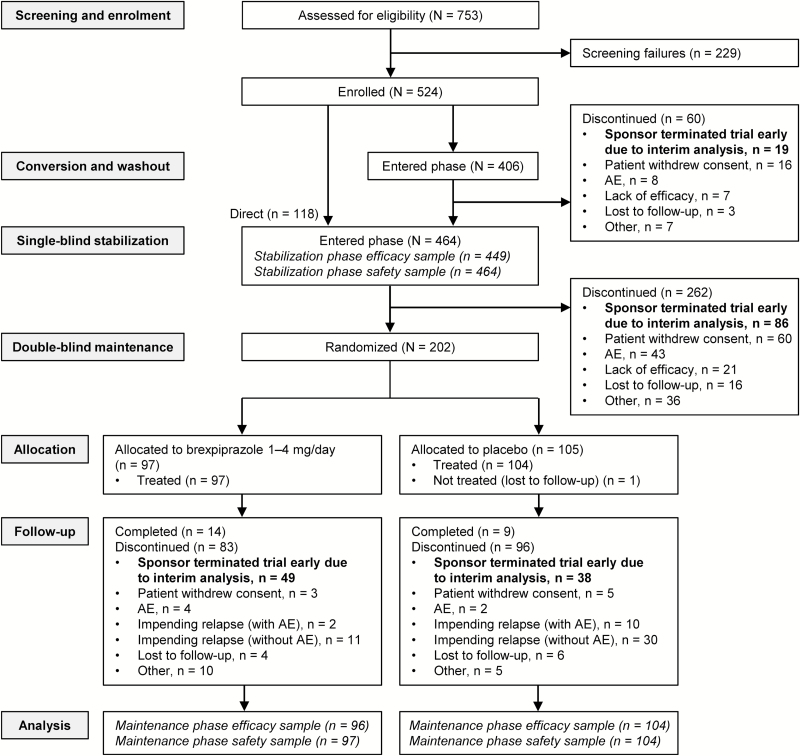

A total of 524 patients were enrolled, 406 of whom entered the conversion phase and 118 entered the stabilization phase directly (Figure 1). Of the 202 patients who met stability criteria, 97 were randomized to brexpiprazole and 105 to placebo. Reasons for treatment discontinuation are given in Figure 1; the most common reasons for discontinuation across the 3 treatment phases were early termination of the trial by the sponsor due to the result of the interim analysis and withdrawal of consent by the patient. Baseline demographics for the 3 treatment phases are shown in Table 1 and were comparable between groups in the maintenance phase.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (Enrolled Population)

| Conversion Phase (n=406) | Single-Blind Stabilization Phase (n=464) | Double-Blind Maintenance Phase (n=202) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brexpiprazole (n=97) | Placebo (n=105) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 39.8 (11.3) | 39.2 (11.2) | 38.8 (10.7) | 41.6 (10.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.5 (6.1) | 27.8 (6.4) | 28.2 (6.7) | 29.1 (6.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 162 (39.9) | 186 (40.1) | 39 (40.2) | 40 (38.1) |

| White, n (%) | 267 (65.8) | 277 (59.7) | 62 (63.9) | 65 (61.9) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age at first diagnosis (y), mean (SD) | 26.6 (8.7) | 25.0 (8.5) | 26.5 (8.2) | 27.9 (8.3) |

| PANSS total score, mean (SD) | 91.1 (8.7) | 84.4 (12.3) | 56.5 (8.7) | 58.1 (8.1) |

| CGI-S score, mean (SD) | 4.6 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) |

| PSP score, mean (SD) | 48.3 (11.3) | 48.0 (11.6) | 50.1 (12.4) | 48.7 (11.7) |

| GAF score, mean (SD) | 46.2 (10.5) | 45.8 (10.4) | 64.3 (9.2) | 63.1 (8.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance.

The mean average daily dose of brexpiprazole at patients’ last visit was 3.4mg in the stabilization phase (n=464) and 3.6mg in the maintenance phase (n=97); 99% of patients (n=96/97) received brexpiprazole 2 to 4mg at their last visit and 1% (1 patient) received 1mg. Due primarily to the early termination of the trial following the interim analysis, only 50 patients (51.5%) were exposed to brexpiprazole for at least 141 days in the maintenance phase (i.e., were treated during week 24).

Efficacy

The first planned interim efficacy analysis, after 45 events of impending relapse, included 167 patients. Brexpiprazole 1 to 4mg/d demonstrated superiority over placebo on the primary analysis, time to impending relapse during the maintenance phase, with a hazard ratio of 0.338 (95% CI 0.174, 0.655; P=.0008, log-rank test).

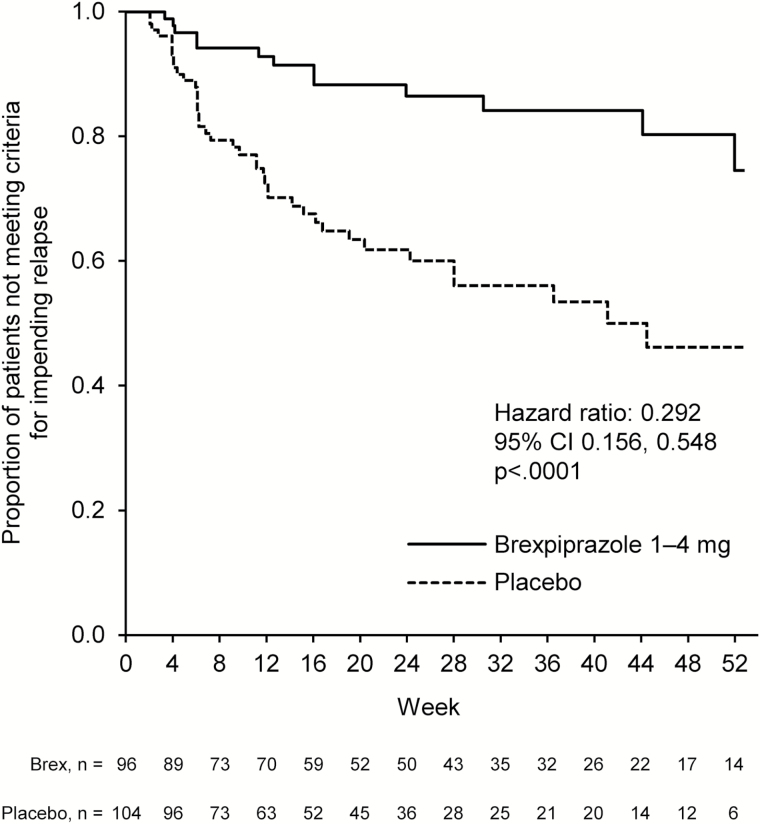

The final efficacy analysis after 53 events of impending relapse included 200 patients. Brexpiprazole 1 to 4mg/d (mean dose at last visit, 3.6mg) demonstrated superiority over placebo on the time to impending relapse during the maintenance phase, with a hazard ratio of 0.292 (95% CI 0.156, 0.548; P<.0001, log-rank test) (Figure 2). The key secondary analysis showed that, in the maintenance phase, the proportion of patients who met the criteria for impending relapse was statistically significantly lower in the brexpiprazole group than the placebo group (13.5% [n=13/96] vs 38.5% [n=40/104], respectively; P<.0001, chi-squared test).

Figure 2.

Time from randomization to impending relapse in the double-blind maintenance phase. The hazard ratio (brexpiprazole vs placebo) and 95% CI were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as term. The P value was calculated using the log-rank test. The analysis was conducted in the maintenance phase efficacy sample.

The following results are for the final analysis. For patients who discontinued, the median time to discontinuation due to any reason in the maintenance phase (other than early termination of the trial by the sponsor) was 169 days with brexpiprazole vs 111 days with placebo, with discontinuation rates of 34.4% and 54.8%, respectively (P=.0014 vs placebo, log-rank test). The proportion of patients still meeting stability criteria at their last (post-baseline) visit in the maintenance phase was 79.2% (n=76/96) in the brexpiprazole group vs 56.7% (n=59/104) in the placebo group (P=.0007, chi-squared test).

During the conversion and stabilization phases, respectively, 1.7% (n=7/406) and 4.5% (n=21/464) of patients withdrew due to lack of efficacy, and 1.0% (n=4/406) and 6.0% (n=28/464) of patients withdrew due to an AE of schizophrenia or psychotic disorder.

Other secondary efficacy analyses are presented in Table 2. In the stabilization phase, there was a mean decrease (improvement) in PANSS total score of 15.13 points from baseline to last visit. Across the 52-week maintenance phase, the PANSS total score was relatively stable in the brexpiprazole group (a least squares mean increase of 3.25 points), whereas a least squares mean increase (worsening) of 11.20 points was observed in the placebo group (LOCF, ANCOVA, P=.0007) (supplementary Figure 2). Due to the trial terminating early (at the time of the first interim analysis), the number of patients with week 52 data for the MMRM analyses was low (brexpiprazole, n=15; placebo, n=9). In the stabilization phase, there was also a mean improvement from baseline to last visit on PANSS subscales, CGI-S, CGI-I, PANSS excited component, and all Marder factor scores. In the maintenance phase, in LOCF analyses, brexpiprazole was favored over placebo at week 52 (P<.01) on PANSS positive subscale, CGI-S, CGI-I, PANSS excited component, and Marder factor (positive symptoms, disorganized thought, and uncontrolled hostility/excitement) scores. Similarly, on the social functioning scales, there was a mean 11.42-point improvement in GAF score from baseline to last visit in the stabilization phase (PSP was not assessed post-baseline in the stabilization phase). In the maintenance phase, brexpiprazole was favored over placebo at week 52 on PSP and GAF scores (LOCF, P<.01). PSP scores improved in both treatment groups during the maintenance phase, with a least squares mean increase of 15.06 points in the brexpiprazole group and 10.31 points in the placebo group (LOCF). Supplementary Figure 3 shows the evolution of PSP scores over time, and Supplementary Figure 4 shows the evolution of GAF scores over time.

Table 2.

Secondary Efficacy Endpoints

| Single-Blind Stabilization Phase (Stabilization Phase Efficacy Sample; n=449) | Double-Blind Maintenance Phase (Maintenance Phase efficacy sample; n=200) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) Change at Last (Post-Baseline) Visit | Baseline Mean (SD) | MMRM analysis | LOCF, ANCOVA | ||||||||

| LS Mean Change (SE) at Week 52 | Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | LS Mean Change (SE) at Week 52 | Treatment Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |||||||

| Brex | Brex | Brex | Placebo | Brex | Placebo | Brex | Placebo | |||||

| PANSS total score | 84.26 (12.33) | -15.13 (15.99) | 56.66 (8.51) | 58.07 (8.13) | 0.61 (3.34) | 6.92 (4.53) | -6.31 (-18.1, 5.46) | .2800 | 3.25 (1.94) | 11.20 (1.77) | -7.95 (-12.5, -3.41) | .0007 |

| [n=449] | [n=447] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| PANSS positive subscale score | 21.35 (4.75) | -4.99 (5.45) | 12.48 (3.66) | 12.63 (3.13) | -1.21 (0.73) | 1.50 (0.99) | -2.71 (-5.20, -0.22) | .0339 | 0.99 (0.64) | 4.17 (0.59) | -3.18 (-4.70, -1.66) | <.0001 |

| [n=449] | [n=447] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| PANSS negative subscale score | 22.14 (4.64) | -3.16 (4.61) | 16.30 (3.46) | 17.00 (3.64) | 1.30 (1.37) | 0.87 (1.71) | 0.43 (-4.14, 5.00) | .8470 | 0.39 (0.54) | 1.63 (0.49) | -1.24 (-2.50, 0.01) | .0516 |

| [n=449] | [n=447] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| CGI-S score | 4.31 (0.78) | -0.73 (0.96) | 3.00 (0.60) | 3.08 (0.60) | -0.23 (0.17) | 0.28 (0.22) | -0.51 (-1.09, 0.06) | .0780 | 0.02 (0.11) | 0.55 (0.11) | -0.53 (-0.79, -0.26) | .0002 |

| [n=449] | [n=449] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| CGI-I score | NA | 2.84 (1.24) a | NA | NA | - | - | - | - | 3.77 (1.26)b | 4.40 (1.32) b | -0.61 (-0.96, -0.25) | .0009 |

| [n=454] | [n=96] | [n=104] | ||||||||||

| PSP score | - | - | 49.82 (12.20) | 48.22 (11.64) | 18.63 (2.76) | 12.55 (3.48) | 6.08 (-2.71, 14.87) | .1677 | 15.06 (1.43) | 10.31 (1.34) | 4.75 (1.31, 8.18) | .0071 |

| [n=94] | [n=100] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=94] | [n=100] | |||||||

| GAF score | 45.82 (10.34) | 11.42 (12.30) | 64.22 (9.00) | 63.00 (8.31) | 5.72 (1.87) | -0.16 (2.37) | 5.88 (-0.06, 11.82) | .0522 | 0.55 (1.38) | -6.01 (1.28) | 6.55 (3.28, 9.83) | .0001 |

| [n=449] | [n=426] | [n=95] | [n=102] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=95] | [n=102] | |||||

| PANSS excited component score | 11.03 (3.44) | -1.89 (3.97) | 6.98 (1.92) | 7.37 (2.50) | -0.04 (0.46) | 1.00 (0.59) | -1.03 (-2.58, 0.51) | .1803 | 0.82 (0.41) | 2.35 (0.38) | -1.54 (-2.52, -0.56) | .0023 |

| [n=449] | [n=447] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| PANSS Marder factor scores | ||||||||||||

| Positive symptoms | 25.46 (5.13) | -5.48 (5.66) | 15.89 (3.99) | 15.80 (3.21) | -1.62 (0.83) | 1.78 (1.05) | -3.40 (-6.05, -0.75) | .0136 | 0.58 (0.66) | 4.02 (0.60) | -3.44 (-4.99, -1.89) | <.0001 |

| Negative symptoms | 21.05 (4.92) | -3.23 (4.81) | 15.07 (3.53) | 16.06 (3.68) | 1.37 (1.39) | 1.06 (1.77) | 0.31 (-4.40, 5.02) | .8927 | 0.34 (0.56) | 1.57 (0.50) | -1.23 (-2.52, 0.07) | .0630 |

| Disorganized thought | 19.98 (3.86) | -3.42 (3.95) | 14.54 (2.89) | 14.31 (3.06) | -0.37 (0.99) | -0.30 (1.24) | -0.07 (-3.32, 3.17) | .9632 | 0.29 (0.48) | 1.97 (0.45) | -1.69 (-2.81, -0.56) | .0035 |

| Uncontrolled hostility/ excitement | 8.58 (3.14) | -1.42 (3.35) | 5.56 (1.76) | 5.72 (2.17) | -0.20 (0.40) | 0.94 (0.50) | -1.14 (-2.46, 0.18) | .0875 | 0.49 (0.37) | 1.75 (0.34) | -1.26 (-2.12, -0.39) | .0046 |

| Anxiety/depression | 9.18 (3.21) | -1.57 (3.42) | 5.59 (1.76) | 6.18 (2.47) | 0.04 (0.43) | 0.28 (0.56) | -0.23 (-1.68, 1.21) | .7437 | 1.17 (0.31) | 1.88 (0.29) | -0.72 (-1.47, 0.03) | .0608 |

| [n=449] | [n=447] | [n=96] | [n=104] | [n=15] | [n=9] | [n=96] | [n=104] | |||||

| Cogstate cognitive test battery | Last (post-baseline) visit, ANCOVA | |||||||||||

| Composite change score c | 0.09 (0.88) | -0.12 (0.70) | 0.10 (0.89) | 0.11 (0.88) | - | - | - | - | 0.06 (0.07) | -0.13 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.01, 0.37) | .0419 |

| [n=441] | [n=161] | [n=82] | [n=82] | [n=82] | [n=82] | |||||||

| Detection task (log10 msec) d | 2.66 (0.17) | 0.02 (0.13) | 2.68 (0.17) | 2.67 (0.17) | - | - | - | - | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | -0.01 (-0.04, 0.03) | .7724 |

| [n=444] | [n=164] | [n=82] | [n=82] | [n=82] | [n=82] | |||||||

| Identification task (log10 msec)d | 2.79 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.10) | 2.80 (0.12) | 2.80 (0.12) | - | - | - | - | -0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | -0.03 (-0.06, 0.00) | .0312 |

| [n=444] | [n=164] | [n=84] | [n=83] | [n=84] | [n=83] | |||||||

| One-card learning task c | 0.92 (0.17) | -0.01 (0.16) | 0.95 (0.18) | 0.94 (0.16) | - | - | - | - | 0.02 (0.02) | -0.04 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | .0321 |

| [n=447] | [n=167] | [n=84] | [n=85] | [n=84] | [n=85] | |||||||

| Groton maze learning task d | 72.5 (46.9) | 0.4 (68.3) | 68.24 (36.15) | 63.21 (27.34) | - | - | - | - | 0.22 (3.26) | 2.43 (3.34) | -2.21 (-11.4, 7.02) | .6371 |

| [n=432] | [n=163] | [n=84] | [n=80] | [n=84] | [n=80] | |||||||

Abbreviations: Brex, brexpiprazole 1–4mg; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; LOCF, last observation carried forward; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed-effect model repeated measures; NA, not applicable; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance; –, not assessed/analysis not performed.

aMean (SD) score at patients’ last (post-baseline) visit.

bMean (SD) score at week 52.

cAn increase in score indicates improvement.

dA decrease in score indicates improvement.

In the maintenance phase, MMRM analyses using observed data (treatment, trial center, visit, treatment–visit interaction, and baseline value as fixed effects; baseline–visit interaction as covariate) were performed, along with LOCF sensitivity analyses using an ANCOVA model (treatment and trial center as factors; baseline value as covariate). In the maintenance phase, CGI-I score was analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel method with LOCF data. For Cogstate analyses in the maintenance phase, an ANCOVA model (treatment as factor; baseline value as covariate) was used.

Regarding the Cogstate computerized cognitive test battery, mean change in scores during the maintenance phase favored brexpiprazole over placebo (P<.05) on the composite score and on 2 of the individual tasks (identification and 1-card learning) at last visit. Cohen’s d for the composite score was 0.298.

Safety

During the stabilization phase, 8.8% of patients receiving brexpiprazole (n=41/464) discontinued due to treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). During the maintenance phase, 5.2% of patients receiving brexpiprazole (n=5/97) and 11.5% of patients receiving placebo (n=12/104) discontinued due to TEAEs. TEAEs leading to discontinuation and the most common TEAEs are described in Table 3, and treatment-emergent EPS-related AEs are described in supplementary Table 1. During the stabilization phase, 57.5% of patients (n=267/464) experienced a TEAE. TEAEs reported by ≥5% of patients receiving brexpiprazole were insomnia, akathisia, agitation, schizophrenia, increased weight, and headache. During the maintenance phase, 43.3% of patients (n=42/97) in the brexpiprazole group had at least one TEAE compared with 55.8% (n=58/104) in the placebo group. No TEAEs had an incidence of ≥5% in the brexpiprazole group and greater incidence in the brexpiprazole group than in the placebo group. TEAEs with an incidence of ≥2% in the brexpiprazole group and greater incidence than in the placebo group are shown in supplementary Figure 5. The majority of TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity. One patient died during the study (stabilization phase) due to a non-self-inflicted gunshot wound, considered by the investigator to be unrelated to brexpiprazole. One patient made a suicide attempt (stabilization phase), also considered by the investigator to be unrelated to brexpiprazole.

Table 3.

Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

| Single-Blind Stabilization Phase (Stabilization Phase Safety Sample; n=464) | Double-Blind Maintenance Phase (Maintenance Phase Safety Sample; n=201) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Brexpiprazole 1–4mg (n=464), n (%) | Brexpiprazole 1–4mg (n=97), n (%) | Placebo (n=104), n (%) | |

| At least one TEAE | 267 (57.5) | 42 (43.3) | 58 (55.8) |

| At least one serious TEAE | 34 (7.3) | 3 (3.1) | 11 (10.6) |

| Discontinuation due to TEAE | 41 (8.8)a | 5 (5.2)b | 12 (11.5)c |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients in the stabilization phase, or in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group in the maintenance phase | |||

| Headache | 23 (5.0) | 6 (6.2) | 10 (9.6) |

| Insomnia | 56 (12.1) | 5 (5.2) | 8 (7.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 16 (3.4) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (6.7) |

| Schizophrenia | 28 (6.0) | 3 (3.1) | 7 (6.7) |

| Psychotic disorder | 5 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.8) |

| Agitation | 30 (6.5) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.9) |

| Akathisia | 42 (9.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Weight increased | 24 (5.2) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Patients with multiple TEAEs were counted only once towards the total.

aSchizophrenia (n=24), psychotic disorder (n=4), suicidal ideation (n=3), hepatic enzyme increased, somnolence (both n=2), nausea, vomiting, alanine aminotransferase increased, blood creatine phosphokinase increased, electrocardiogram QT prolonged, akathisia, insomnia, libido increased, major depression (all n=1).

bSchizophrenia (n=2), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insomnia, psychotic disorder (all n=1).

cSchizophrenia (n=6), psychotic disorder (n=5), suicidal ideation (n=1).

During the stabilization phase, there was a mean weight increase of 0.8kg, and 11.3% (n=52/462) of patients experienced potentially clinically relevant weight gain (≥7% increase). During the maintenance phase, patients had a mean weight decrease from baseline to their last visit in the brexpiprazole (-0.3kg) and placebo (-2.2kg) groups, and the incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight gain was 5.2% in the brexpiprazole group compared with 1.0% in the placebo group.

On formal EPS rating scales, there were small changes in score during the stabilization phase and no differences between brexpiprazole and placebo during the maintenance phase (supplementary Table 2). Mean changes from baseline to last visit in metabolic laboratory parameters and QT interval were small. In general, the proportions of patients with treatment-emergent suicidality or with treatment-emergent categorical increase in prolactin, lipids, glucose, weight, or QT interval were small in the stabilization phase, and comparable to placebo in the maintenance phase (supplementary Table 3). The incidence of a ≥50-mg/dL increase in fasting triglycerides was higher in the brexpiprazole group (16.3%) than in the placebo group (7.4%), as was a shift in fasting triglyceride level from normal (<150mg/dL) to high (200 to <500mg/dL) (7.0% vs 0.0%).

Discussion

This is the first long-term, controlled, clinical trial of a new agent, brexpiprazole, as maintenance treatment for schizophrenia. In this trial, oral brexpiprazole was an efficacious maintenance treatment for schizophrenia, as demonstrated by a statistically significantly longer time to impending relapse compared with placebo in stabilized patients. The proportion of patients in the maintenance phase who experienced impending relapse with brexpiprazole was 13.5% compared with 38.5% for placebo (the hazard ratio was 0.292; thus, brexpiprazole reduced the risk of impending relapse by 71% compared with placebo). These impending relapse rates are comparable to those in placebo-controlled trials of similar design: oral lurasidone 29.9%, placebo 41.1% (Tandon et al., 2014); oral paliperidone extended-release 25.0%, placebo 52.7% (Kramer et al., 2007); long-acting injectable aripiprazole 10.0%, placebo 39.6% (Kane et al., 2012); and long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate 17.6%, placebo 47.8% (Hough et al., 2010); and below those in a placebo-controlled maintenance trial with no stabilization phase: oral aripiprazole 33.8%, placebo 57.0% (Pigott et al., 2003).

The efficacy of brexpiprazole as maintenance treatment for schizophrenia was also supported by secondary efficacy measures. During the brexpiprazole stabilization phase, clinical symptomatology improved, as assessed by schizophrenia rating scale scores. During the double-blind maintenance phase, the benefits were generally maintained over 1 year with brexpiprazole, whereas scores worsened with placebo (LOCF analyses). The efficacious maintenance dosage of brexpiprazole in this trial was in the range of 2 to 4mg/d, as indicated by the majority of patients (99%) receiving brexpiprazole 2mg, 3mg, or 4mg at their last visit (mean 3.6mg).

Deficits in psychosocial domains are a core feature of schizophrenia, and therefore social functioning is an important outcome parameter for evaluating successful long-term treatment (Burns and Patrick, 2007; Nasrallah et al., 2008). In this study, social functioning was measured using the GAF and PSP rating scales. Mean GAF score improved in the stabilization phase; the benefits were maintained with brexpiprazole in the maintenance phase, whereas placebo showed worsening (LOCF analysis). PSP scores (changes measured in the maintenance phase only) showed improvements with brexpiprazole that were above the threshold for clinically meaningful response in stabilized patients with schizophrenia (an increase of 4–7 points) (Nasrallah et al., 2008). Benefits were also observed with placebo on the PSP in this clinical trial setting.

The Cogstate computerized cognitive test battery favored brexpiprazole over placebo, with a composite score Cohen’s d of 0.298. As defined by Cohen, this is a small, but clinically meaningful, effect size (Cohen, 1988). Cognitive deficits are a core component of schizophrenia, present at early stages and in the absence of antipsychotic medication, and strongly linked to vocational and functional impairments (Bowie and Harvey, 2006; Fatouros-Bergman et al., 2014). Brexpiprazole showed benefits over placebo (P<.05) on 2 of 4 individual cognitive tasks, consistent with previous findings that no drug has a uniform positive cognitive profile in schizophrenia (Désaméricq et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2015).

No unexpected safety issues were identified with brexpiprazole treatment. Though varying between agents, antipsychotic treatment has been associated with weight gain, metabolic problems, EPS and activating side effects (such as akathisia), sedation, and prolactin increases (Kumar and Sachdev, 2009; Leucht et al., 2013). The incidence of AEs, including sedating side effects, was low in this trial and comparable to those reported in short-term, fixed-dose trials of brexpiprazole in schizophrenia (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015). Activating side effects in the stabilization phase (insomnia [12.1%], akathisia [9.1%], agitation [6.5%]) occurred with similar incidence to those observed in the short-term pivotal trials (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015). These activating AEs had generally resolved by the maintenance phase. A mean weight increase of <1kg was observed in the stabilization phase, and mean weight decreased in both groups in the maintenance phase. Brexpiprazole was associated with only small changes in metabolic parameters and QT interval.

A limitation of this trial is the small number of patients who completed the study (23 of 524 enrolled patients, 4.4%), leaving the MMRM analyses underpowered at week 52. Across the 3 treatment phases, the main reason for discontinuation was early termination of the trial following the results of the interim analysis (n=192). Other common reasons for discontinuation (≥10% of enrolled population), aside from impending relapse, were withdrawal of consent by the patient (n=84) and AEs without impending relapse (n=57). The majority of these discontinuations occurred in the stabilization phase, where 60 patients (12.9%) withdrew consent, and 43 patients (9.3%) discontinued due to AEs (of which 28 were schizophrenia or psychotic disorder). Withdrawal of consent may arise because patients have underestimated the burden of participating in the study, or due to a lack of perceived efficacy and/or insight. In previous maintenance treatment trials, the incidences of discontinuation in the oral stabilization phases were highly variable: lurasidone, 14.2% withdrew consent, 12.3% withdrew due to AEs (ClinicalTrials.gov); paliperidone extended-release, 5.1% withdrew consent, 1.6% withdrew due to AEs (Kramer et al., 2007); and aripiprazole, 4.1% withdrew consent, 2.0% withdrew due to AEs (Kane et al., 2012). In addition to the differences between treatments, this variation may be attributed to differences in study design, notably, variation in the length of the stabilization phase between studies (of which, up to 36 weeks in the present study was the longest), differences in blinding, and the presence or lack of a prior conversion phase. Due to the high rate of discontinuation in the present study, the trial population may not be representative of the population intended to be analyzed. Taken together, these limitations indicate that long-term treatment with brexpiprazole is appropriate for those patients who can tolerate, and respond, to brexpiprazole.

There are ongoing concerns regarding the use of placebo in clinical trials, since placebo is associated with a risk of harm by failing to prevent relapse (Emsley and Fleischhacker, 2013). However, clinical regulatory guidelines of the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency state that the use of a placebo arm is appropriate in a randomized withdrawal trial in stabilized patients, since this trial design minimizes exposure to placebo (US Food and Drug Administration, 2012; European Medicines Agency, 2012). In the present trial, exposure to placebo was to be further minimized by 2 planned interim analyses to halt the study as soon as efficacy was demonstrated. The risk to patients receiving placebo was also minimized, since patients were carefully monitored for early indicators of worsening so that serious relapse could be prevented with appropriate active treatment (Emsley and Fleischhacker, 2013). In general, in a relapse prevention trial, a placebo arm may be justified to establish assay sensitivity (European Medicines Agency, 2012). Inclusion of a placebo control is also believed to reduce the cost and duration of a clinical trial, since it is generally easier to distinguish a new medication from placebo than from a standard effective drug; as a consequence, this will reduce the number of patients exposed to the potential adverse effects of a new medication (Carpenter et al., 2003). Finally, standard drugs are not efficacious for all patients and all aspects of schizophrenia and are associated with significant side effects; thus, there are good reasons to seek more effective and safer treatment options (Carpenter et al., 2003).

In summary, in patients with acute schizophrenia who responded to brexpiprazole and met stability criteria, brexpiprazole was an efficacious option as maintenance therapy over the course of 1 year, with an incidence of AEs comparable to placebo and a safety profile similar to that observed in short-term studies. Future research should attempt to replicate this result in a naturalistic setting and to better predict which patients are good candidates to receive brexpiprazole in the long term.

Statement of Interest

W. Wolfgang Fleischhacker is a consultant to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S. Mary Hobart, John Ouyang, Andy Forbes, Stephanie Pfister, Robert D. McQuade, William H. Carson, Raymond Sanchez, and Margareta Nyilas are full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. Emmanuelle Weiller is a full-time employee of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Writing support was provided by Dr Chris Watling of Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd. The authors are entirely responsible for the scientific content of the paper.

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. (Princeton, NJ, USA).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Salkever D, Slade EP, Peng X, Conley RR. (2010) The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 10:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR. (1989) A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. (2006) Cognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2:531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Patrick D. (2007) Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116:403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Jr, Appelbaum PS, Levine RJ. (2003) The Declaration of Helsinki and clinical trials: a focus on placebo-controlled trials in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 160:356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov (2014) PEARL Schizophrenia Maintenance. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01435928 Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01435928 Accessed 25 April 2016.

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, Hobart M, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Eriksson H. (2015) Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 172:870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R; Risperidone-USA-79 Study Group (2002) A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 346:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Désaméricq G, Schurhoff F, Meary A, Szöke A, Macquin-Mavier I, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Maison P. (2014) Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, Harvey BH. (2013) The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R, Fleischhacker WW. (2013) Is the ongoing use of placebo in relapse-prevention clinical trials in schizophrenia justified? Schizophr Res 150:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) (2012) Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products, including depot preparations in the treatment of schizophrenia EMA/CHMP/40072/2010 Rev. 1. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/ 2012/10/WC500133437.pdf Accessed 25 April 2016.

- Fatouros-Bergman H, Cervenka S, Flyckt L, Edman G, Farde L. (2014) Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 158:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker WW, Sanchez R, Perry PP, Jin N, Peters-Strickland T, Johnson BR, Baker RA, Eramo A, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Walling D, Kane JM. (2014) Aripiprazole once-monthly for treatment of schizophrenia: double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority study. Br J Psychiatry 205:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. (1976) ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ; WFSBP Task force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia (2013) World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry 14:2–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M. (2010) Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 116:107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigooka J, Nakamura J, Fujii Y, Iwata N, Kishimoto T, Iyo M, Uchimura N, Nishimura R, Shimizu N; ALPHA Study Group (2015) Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly in Asian patients with schizophrenia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority study versus oral aripiprazole. Schizophr Res 161:421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM. (2007) Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry 68:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, Jin N, Johnson BR, Forbes RA, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Fleischhacker WW. (2012) Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 73:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Skuban A, Ouyang J, Hobart M, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Eriksson H. (2015) A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled Phase 3 trial of fixed-dose brexpiprazole for the treatment of adults with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 164:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, Simpson G, Maciulis V, Kushner S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Eerdekens M. (2007) Paliperidone extended-release tablets for prevention of symptom recurrence in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 27:6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Sachdev PS. (2009) Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry 22:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, Kreyenbuhl J; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines (2004) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry 161:1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Salanti G, Davis JM. (2012) Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379:2063–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, Kissling W, Stapf MP, Lässig B, Salanti G, Davis JM. (2013) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 382:951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Sugino H, Akazawa H, Amada N, Shimada J, Futamura T, Yamashita H, Ito N, McQuade RD, Mørk A, Pehrson AL, Hentzer M, Nielsen V, Bundgaard C, Arnt J, Stensbøl TB, Kikuchi T. (2014) Brexpiprazole I: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel serotonin–dopamine activity modulator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G. (1997) The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 58:538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruff P, Thomas E, Cysique L, Brew B, Collie A, Snyder P, Pietrzak RH. (2009) Validity of the CogState brief battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 24:165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. (2008) Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev 30:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, Valladares A, Lizán L, San L, Escobar R, Paz S. (2011) Validation of the Excited Component of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-EC) in a naturalistic sample of 278 patients with acute psychosis and agitation in a psychiatric emergency room. Health Qual Life Outcomes 9:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. (2000) Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah H, Morosini P, Gagnon DD. (2008) Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with stable schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 161:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen RE, Levander S, Kjaersdam Telléus G, Jensen SO, Østergaard Christensen T, Leucht S. (2015) Second-generation antipsychotic effect on cognition in patients with schizophrenia – a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 131:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Olver J, Norman T, Piskulic D, Maruff P, Snyder PJ. (2009) A comparison of the CogState Schizophrenia Battery and the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Battery in assessing cognitive impairment in chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 31:848–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR, Torbeyns AF, Stock EG, Ingenito GG; Aripiprazole Study Group (2003) Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study. J Clin Psychiatry 64:1048–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. (2011) The Columbia – Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson S, Joshi K, Mansour M, Adams CE. (2013) Intermittent drug techniques for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 39:960–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM, Angus JW. (1970) A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Loebel A, Phillips D, Pikalov A, Hernandez D, Mao Y, Cucchiaro J. (2014) EPA-1722 – A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of lurasidone for the maintenance of efficacy in patients with schizophrenia. Abstracts of the 22nd European Congress of Psychiatry. Eur Psychiatry 29(Suppl 1):1–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) (2012) Draft guidance for industry. Enrichment strategies for clinical trials to support approval of human drugs and biological products Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/ guidances/ucm332181.pdf Accessed 25 April 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.