Abstract

The overall prognosis of bladder cancer has not been improved over the last 30 years and therefore, there is a great medical need to develop novel diagnosis and therapy approaches for bladder cancer. We developed a multifunctional nanoporphyrin platform that was coated with a bladder cancer-specific ligand named PLZ4. PLZ4-nanoporphyrin (PNP) integrates photodynamic diagnosis, image-guided photodynamic therapy, photothermal therapy and targeted chemotherapy in a single procedure. PNPs are spherical, relatively small (around 23 nm), and have the ability to preferably emit fluorescence/heat/reactive oxygen species upon illumination with near infrared light. Doxorubicin (DOX) loaded PNPs possess slower drug release and dramatically longer systemic circulation time compared to free DOX. The fluorescence signal of PNPs efficiently and selectively increased in bladder cancer cells but not normal urothelial cells in vitro and in an orthotopic patient derived bladder cancer xenograft (PDX) models, indicating their great potential for photodynamic diagnosis. Photodynamic therapy with PNPs was significantly more potent than 5-aminolevulinic acid, and eliminated orthotopic PDX bladder cancers after intravesical treatment. Image-guided photodynamic and photothermal therapies synergized with targeted chemotherapy of DOX and significantly prolonged overall survival of mice carrying PDXs. In conclusion, this uniquely engineered targeting PNP selectively targeted tumor cells for photodynamic diagnosis, and served as effective triple-modality (photodynamic/photothermal/chemo) therapeutic agents against bladder cancers. This platform can be easily adapted to individualized medicine in a clinical setting and has tremendous potential to improve the management of bladder cancer in the clinic.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, photodynamic therapy, photothermal therapy, nanotechnology

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth and eleventh most common cancer among men and women, respectively[1]. Approximately 80% of patients have non-myoinvasive bladder cancer at diagnosis that is treated with transurethral resection followed by intravesical instillation of therapeutic agents, such as Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, in high-risk patients. Transurethral resection is associated with microscopic residue tumor in at least a third of the cases regardless of the experience of the surgeon [2]. This treatment is associated with a recurrence rate of approximately 60% at two years [3], and disease progression to invasive cancer in around 25% of cases. Because of the high recurrence rate, surveillance with intrusive, uncomfortable and costly cystoscopy is performed once every few months during the first two years and at longer intervals for life. These surveillance procedures make bladder cancer the most costly cancer per case among all cancer types [4]. The overall prognosis of bladder cancer has not changed over the last three decades [5]. Therefore, there is a great unmet medical need for the diagnosis and therapy for bladder cancer.

Photodynamic diagnosis and therapy have been an attractive alternative modality in the management of bladder cancer [6–9], as it is minimally invasive, relatively tumor selective, and has low risk for development of resistance [10]. Compared to traditional white light transurethral resection, Photodynamic diagnosis assisted transurethral resection significantly improved the detection of bladder cancer and lowered the risk for recurrence [8, 11–14] Photosensitizers, Photofrin® and Hexaminolevulinate, had been approved in Canada and USA, respectively, for bladder cancer, while others, such as 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), 3-(1′-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH), Hematoporphyrin derivate, and chlorin E6, are at the different stages of clinical development[15–17].

However, current photosensitizers have poor selectivity, a low absorption band, poor bioavailability, low efficiency[18], and no photothermal effect or ability to co-deliver chemotherapeutic drugs and thus are limited in their clinical utility. To address these limitations, we introduce a small (<25 nm), multi-functional, highly water soluble micelle combining photodynamic therapy with imaging, cancer-specific drug delivery and extended drug retention. This enhanced functionality results from the self-assembly of micelles combining two species of cholic acid-polymer conjugates: 1) a porphyrin-cholic acid (CA)-polyethelene glycol (PEG) conjugate, and 2) a molecularly-targeted, cholic acid-polyethelene glycol conjugate [19] (Fig. 1A). We have previously reported the discovery of a bladder cancer-specific cyclic peptide named PLZ4 (amino acid sequence: cQDGRMGFc). PLZ4 specifically binds to the αvβ3 integrin on bladder cancer cells even in the presence of bladder inflammation [20, 21]. We previously demonstrated that PLZ4-coated micelles (PMs, a mixture of PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-CA8 telodendrimers) specifically delivered the drug paclitaxel to canine and human bladder tumor cells in vitro and in vivo, resulting in superior anti-cancer efficacy in comparison to drug-loaded non-targeted micelles and free drug [22]. Thus, we mixed original PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 (providing molecular targeting) and newly introduced PEG5k-Por4-CA4 (providing photodynamic diagnosis/therapy) to form PLZ4-nanoporphyrin (PNPs) which address current clinical challenges in treating bladder cancers.

Figure 1. Illustration and characterization of PLZ4-Nanoporphyrins (PNPs).

(A)Diagram of PNPs spontaneously assembled by the Pyropheophorbide a -containing-telodendrimer(PEG5k-Por4-CA4) and PLZ4 conjugated telodendrimer (PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8). Moreover, PLZ4-micelle (PM) was a mixture of PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-CA8, while nanoporphyrin(NP) was a mixture of PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-Por4-CA4 (B)Transmission electron microscopy images and (C) particle size distribution of PNPs and PNP-DOX. (D) The drug release profiles of free DOX, PM-DOX, and PNPs loaded with DOX (PNP-DOX). (E) Near infrared fluorescence (NIRF, left Y-axis) and singlet oxygen production (indicator: SOSG, right Y-axis) of PNPs in PBS (intact) or SDS (dissociated) after light exposure (20 J/cm2). Solid triangle: NIRF of PNPs in SDS; solid circle: NIRF of PNPs in PBS. Open triangle: SOSG production of PNPs in SDS; open circle: SOSG production of PNPs in PBS. (F) The relationship between temperature change and NIRF of PNPs in PBS or SDS as well as corresponding pyropheophorbide a (Ppa) in DMSO after light exposure (20J/cm2). (G) Pharmacokinetics of DOX after administration of free DOX and PNP-DOX (5mg Dox/kg). (H) Fluorescence microscopic observation for selective uptake of PNPs in the normal canine bladder urothelial cells (URO: no fluorescence, large polygonal cells with abundant cytoplasm) co-cultured with 5637 bladder cancer cells (BC: DiO pre-labeled, green). (160×, Bar=150 μm).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a targeted nanoparticle platform that is able to integrate such a broad range of clinically relevant functionalities in a single nano-formulation specifically for bladder cancer. It has the great potential to significantly change the clinical management paradigm of bladder cancer.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and characterization of PLZ4-Nanoporphyrins (PNPs)

The pyropheophorbide a containing telodendrimer (PEG5k-Por4-CA4, Fig. 1A) was synthesized via solution-phase condensation reactions according to our published method [23]. Our previously reported PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 telodendrimer was synthesized by the conjugation of alkyne-derivatized bladder cancer targeting ligand PLZ4 (CPC scientific, Sunyvale, CA)[24, 25] to PEG5k-CA8 telodendrimer via click chemistry [26–28].

PNPs were obtained via a mixed micelle strategy. Briefly, 10 mg of PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-Por4-CA4 (Fig. 1A) were dissolved in the chloroform, and evaporated on a rotavapor to obtain a homogeneous dry polymer film. The film was reconstituted in 1 ml PBS, followed by sonication for 30 min, allowing the sample film to disperse into PNP solution. DOX was loaded into PNPs by following the same solvent evaporation method after mixing neutralized DOX with telodendrimers[29]. PNP-DOX stock (20 mg of PNP/ml) contains 2 mg/ml Pyropheophorbide a and 1 mg/ml DOX. Finally, the nanoparticle solution was filtered with 0.22 μm filter to sterilize the sample. Similarly, a PLZ4-micelle (PM) formed from a mix of PLZ4-PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-CA8, while nanoporphyrin (NP) was formed from a mix of PEG5k-CA8 and PEG5k-Por4-CA4.

The particle size and morphology were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (Microtrac, Montgomeryville, PA) and transmission electron microscopy (Philips, CM-120, Andover, MA), respectively. The drug release profiles of the DOX-loaded nanoparticles was investigated using dialysis method in the presence of 10% FBS as described previously[22].

Pharmacokinetic study

Four Jugular vein cannulated rats (Harlan Laboratories, Livermore, CA) were employed for the pharmacokinetic study. Each rat received 5 mg/kg DOX or PNP-DOX (5 mg/kg DOX and 100 mg/kg PNPs (10 mg/kg Pyropheophorbide a). Fifty microliters of blood were collected at different time points and fluorescence was measured.

Cellular uptake and ROS production

Human bladder cancer 5637 cells (ATCC®, Manassas, VA) were seeded into 96-well plates overnight. After treatment with various concentrations of PNPs and NPs for 4 hours, free drugs were washed and cells were lysed with 100 μl of lysis buffer for 30 minutes with shake. Fluorescence was measured by ELISA reader (Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

For intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) productions, 5637 cells were treated with 10 μg/ml PNPs (Pyropheophorbide a : 2μg/ml) for 2 hours and washed by PBS for 3 times in suspension. Cells were then loaded with 10μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) (Sigma) for 30 minutes followed by 4.2 J/cm2 light treatment (Omnilux New-U LED panel with 635 nm light, Clifton Park, NY). ROS production was then analyzed by flow cytometry. Methods for assessment of the tissue level of ROS production were described previously[19].

To specifically confirm the signet oxygen generation in vitro, we incubated singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG, Sigma) with different concentrations of PNPs with or without SDS. SOSG and porphyrin fluorescence were measured by ELISA reader.

Confocal microscope – selective uptake and cellular bio-distribution

Primary normal dog urothelial cells [22] were co-cultured with DiO (Sigma) dye labeled 5637 cells. Plate was treated with 10 μg/ml PNPs for 2 hours and imaging was acquired under fluorescence microscope without wash. For subcellular bio-distribution study, 5637 cells were treated with DOX-loaded PNPs. Images were then obtained through confocal microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL). To detect intracellular Glutathione changes, Thiol Tracker™ Violet Glutathione Detection Reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was incubated for 30 minutes after treatment and slides were analyzed by confocal microscope.

Cell viability, caspase 3/7 activities, and mitochondria potentials

Cell viability was measured by WST-8 cell proliferation kit (Cayman chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) as previously described [19]. SensoLyte® Caspase3/7 Assay Kit (Anaspec, Fremont, CA) was used to detect Casepase3/7 production. Mitochondria membrane potential changes and cell viability were measured by DiOC6(3) (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Propidium iodide (PI) as previously described[19].

Othotopic bladder cancer model in mouse and intravesical photodynamic diagnosis

One million mouse bladder cancer MB49-GFP-Luc cells (MB49 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Yi Luo from University of Iowa. MB49 cells transfected with Lentivirus vector pCCLc-MNDU3-LUC-PGK-EGFP-WPRE, kindly provided by UC Davis Vector Core.) were implanted into 4–5 weeks B6/C57 female mice (Harland) bladder which was pretreated with poly-L-lysine via 24G iv catheter. After 1 week, tumor establishment was confirmed by Luciferase activity.

To evaluate the photodynamic diagnosis function of PNPs, different concentrations of PNPs were administrated into the bladder via the urethra as indicated. The bladder was washed with PBS and the animal was terminated. Major organs and bladder were harvested for an ex vivo imaging study. The bladder was later cut open to expose the lumen and imaging was acquired using Kodak imaging station (Kodak, Rochester, NY), and Leica 3D large scale confocal microscope.

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) bladder cancer mouse model for fluorescence imaging

The animal protocol was approved by UC Davis IACUC (No. 17763). Three different PDX models (BL269, BL440, BL645, and BL293, The Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA) were established in NOD scid gamma(NSG) mice (The Jackson laboratory) by subcutaneously implanting tissue in the flank or into bladder wall [28]. After PDXs were established, mice were intravesically administrated PNPs for local diagnosis. Bladders from both PDX models and normal mice were harvested for cryosections. Metamorph software was used to measure the fluorescence intensity at the certain depth indicated from the surface at 5 different random areas. For systemic application, mice were intravenously given 5-ALA (100 mg/kg), PNPs and PNP-DOX (eq. 50 mg/kg of PNPs or 5 mg/kg pyropheophorbide a, and 2.5 mg/kg DOX). Whole body imaging was acquired at indicated times. After imaging, animals were injected with FITC-Dextran (Sigma) for blood vessel staining and then sacrificed immediately. Tumors and other major organs were harvested for ex vivo imaging. Cryosection of tumor was observed under fluorescence microscope.

In vivo PNP mediated photodynamic therapy in an orthotopic PDX model and microbubble contrast enhanced ultrasonography

Two days post-implantation, mice were treated with PBS, 1 mg/ml DOX, or 5 mg/ml PNPs for 1 hour. After a PBS wash, the PNP treated group was further treated with 0.2 W laser light (690nm, Shanghai Xilong Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd, China) via a 600 micron optical fiber for 3 minutes. Mice were monitored daily for appearance, activity, and urine color. One month later, ultrasound imaging was used to visualize the bladder tumor burden: both B-mode images (before microbubble injection) and contrast pulse sequencing images (after microbubble injection) with a dose of 5 × 107 microbubbles per mouse. Mice were then sacrificed, and bladders were harvested for histopathology evaluation.

In vivo anti-cancer efficacy study in bladder cancer PDX mice model

Six NSG mice with subcutaneous BL293 PDX per group received PBS, PM-DOX, PNP, and PNP-DOX, and tumor were locally illuminated with a diode laser system (Applied Optronics, South Plainfield, NJ) with 690 nm wavelength after 24 hours at dose indicated weekly for 3 times. Tumor size, body weight, and other behavior/appearance changes were monitored every 2–3 days. For histopathology evaluation, tumors were harvested 24 hour post illumination.

Tumor temperature measurement

NSG mice bearing subcutaneous BL293 PDX were intravenously injected with PBS, 5-ALA, PNPs, and PNP-DOX After 24 hours, mice were treated with light as indicated. Tumor temperature was measured using FLIR infrared camera (FLIR systems, Boston, MA).

Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least 3 times unless otherwise specified. Results were presented in mean ± S.D. Student t-test was used for statistical analysis. p<0.05 was considered as significant. Data organization and analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism. Quantitative imaging analysis was performed using Image J.

Results

Synthesis and Characterization of PLZ4-nanoporphyrins (PNPs)

PNPs imaged before and after doxorubicin (DOX) loading (PNP-DOX) were spherical in shape (Fig. 1B) with a particle diameter of 22±7 and 23±6 nm for PNPs and PNP-DOX, respectively (Fig. 1C). The release of DOX from PNP-DOX was significantly slower than PLZ4-micelles(PM) in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Fig. 1D). Upon light exposure in PBS, PNPs were intact, the fluorescence was quenched (Fig. 1E left y-axis) and there was little singlet molecular oxygen production as detected by Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green® (SOSG, right y-axis). In contrast, in the presence of ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), PNPs were partially disassociated, resulting in concentration-dependent increase of fluorescence and singlet oxygen production (Fig. 1E). Free pyropheophorbide a has poor water solubility (precipitated in PBS) and showed strong fluorescence when dissolved in organic solvent dimethyl sulfoxide under identical concentrations (data not shown). Consistent with the previous findings [19], when the nanoporphyrins were intact and fluorescence was quenched, light was absorbed and released as heat. There was a negative correlation between heat production and fluorescence of the PNP solution under light exposure (Fig. 1F). In PBS when PNPs were intact, the temperature reached 59°C in 20 seconds associated with little singlet oxygen production under light exposure at a concentration of 1 mg/ml, while Pyropheophorbide a dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at the same concentration reached 39°C (Fig. 1F) with much higher singlet oxygen production. SDS partially dissolved PNPs, leading to heat release and singlet oxygen production between intact PNPs and free Pyropheophorbide a.

We next determined the effect of the PNP formulation on the pharmacokinetics of DOX which is used as a first-line therapeutic for bladder cancer (Fig. 1G). Hydrophobic free DOX quickly diffused into tissue and was cleared from circulation within 2 min after intravenous administration (T1/2α=1.66min; T1/2β=251.74min). PNP-DOX restricted tissue distribution and significantly improved the blood circulation time of DOX (T1/2α=22.78; T1/2β=1219.86 min). PNP-DOX exhibited 10.6 times higher area under the curve (AUC) than free DOX (AUC=20.67 vs 1.96 μg·24 h/ml) (Table S1).

Selective uptake of PNPs by bladder cancer cells

The specificity of photosensitizer delivery to cancer cells is critically important for photodynamic diagnosis and therapy. Firstly, we showed that PNP could be specifically taken up by human bladder cancers in a time-dependent manner (Fig S1A) and primarily distributed in the cytoplasm with a membrane and perinuclear pattern (Fig S1B). Next, we co-cultured normal urothelial cells (not recognized by PLZ4[28]) with DiO-labeled human bladder cancer cells (green) and exposed this cell mixture to PNPs. Cellular internalization of PNPs (red) was highly selective to bladder cancer cells and not to adjacent normal urothelial cells (Fig. 1H). Because PNPs in culture medium were intact and the fluorescence was quenched, we did not observe fluorescence overlaying normal urothelial cells even without washing to remove the medium. Similar results were confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. S2A). Consistent with our prior results, we confirmed that surface PLZ4 significantly enhanced PNP internalization by bladder cancer cells as compared with non-PLZ4-coated nanoporpyrin, resulting in enhanced cytotoxicity after light treatment (Fig. S2B&C).

In vivo PNP mediated photodynamic diagnosis in orthotopic bladder cancer models

We next evaluated the potential application of PNPs in photodynamic diagnosis of bladder cancer after intravesical application. In this experiment, we studied mice carrying orthotopic bladder cancer established from a GFP expressing MB49 cell line. MB49 cells could also be recognized by PLZ4 (Fig S3) and are a highly reliable model to establish superficial bladder cancers [30]. After intravesical application, fluorescence was observed only in the bladder, indicating limited systemic absorption (Fig. S4A). After the bladders were harvested and prepared (Fig. S4B), PNP fluorescence was detected as early as 30 minutes within bladder cancer cells and increased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and S4C&D). In contrast, normal urothelium(GFP-) had minimal PNP uptake as demonstrated by minimal red fluorescence and confirmed by histopathology(Fig. 2A). The bladder cancer specific uptake was further confirmed by large scale confocal microscopy with higher resolution imaging (Fig. 2B). Bladder cancer lesions (as small as 1 mm in diameter) could be detected even with a low concentration of PNPs (1 mg/ml, or 0.2 mg/ml pyropheophorbide a) on fresh unfixed full thickness bladder samples (Fig. S4D). Similar results were confirmed in an orthotopic model arising from human bladder cancer UMUC-3 (Fig. S5).

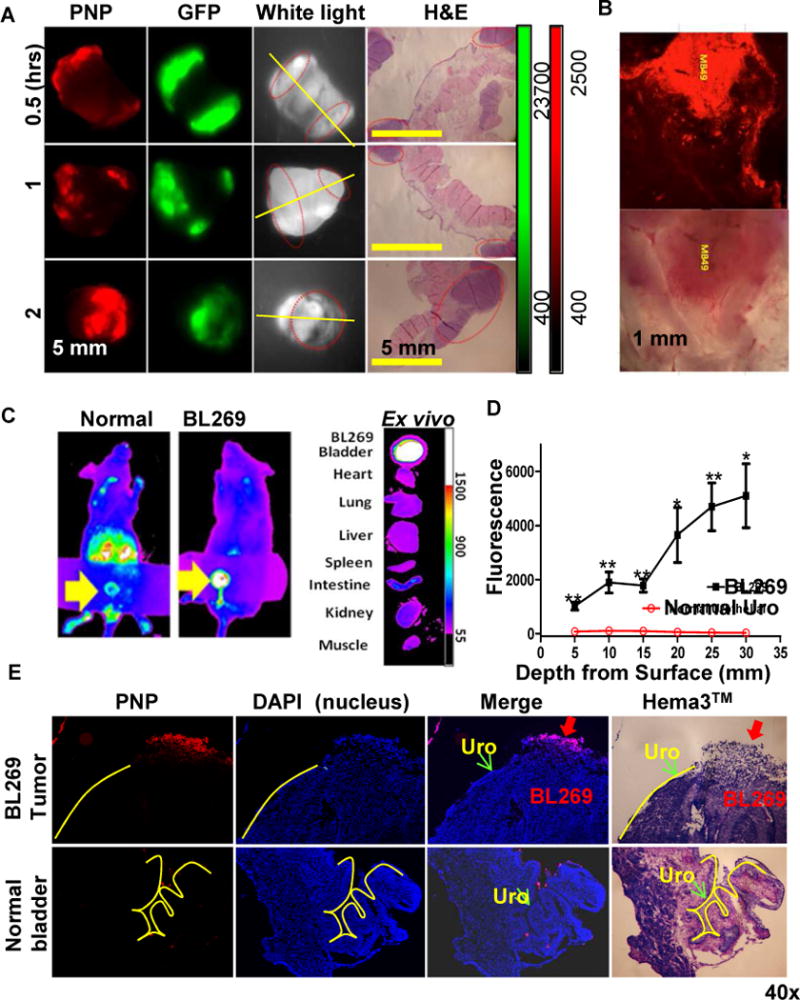

Figure 2. Photodynamic diagnosis of orthotopic mouse bladder cancer in vivo.

(A) PNPs mediated intravesical photodynamic diagnosis using Kodak imaging station in orthotopic mouse bladder cancer model. Mouse with established MB49-GFP-Luc bladder cancers were intravesically injected with 10 mg/ml PNPs (pyropheophorbide a: 2 mg/ml) using 26G blunt needle via urethra. After 2 hours, bladder and other major organs were harvested and imaged in the GFP (tumor cells) and NIRF channel (PNP uptake) using Kodak imaging station. Yellow line: cut line for histopathology; red circles: tumor locations. (B) Large scale 3-D confocal imaging (Leica) for PNP mediated photodynamic diagnosis in orthotopic mouse MB49 bladder cancer model. (C) Uptake of PNPs in an orthotopic PDX BL269 and other organs after intravesical administration of PNPs. (D) The penetration depth analysis between lumen exposed tumor sites and normal urothelium Cryosection was performed on bladder BL269 PDX samples. The fluorescence intensity was measured using Metamorph image analysis software at different spots and depth from lumen surface of tumor (such as red arrow) versus normal urothelial areas (such as green arrow). (p<0.01, t-test). (E) A representative cryosection showing selective uptake of PNPs by PDX bladder cancers (red arrow) but not normal urothelial cells (yellow lines).

To further validate the clinical application, we studied the in vivo PNP uptake using a bladder cancer patient-derived xenograft (PDX) that was developed from unselected uncultured clinical bladder cancer specimens. We previously showed that PDX maintained the morphological fidelity and 92–97% genetic aberrations of parental patient cancers [31], suggesting that studies in PDXs can more likely be directly translated into clinical applications. Immunodeficient NSG mice carrying orthotopic PDX BL269 could be detected after intravesical administration of PNPs (Fig. 2C). Only the bladders implanted with BL269 were positive for PNP uptake; other major organs, including a normal bladder, were negative. Cross-sections of a normal bladder and bladder carrying orthotopic PDX showed that PNPs could penetrate to 30 μm in depth. The fluorescence signal at the same depth is 30–50 times higher than that of normal urothelium (p<0.001, Fig. 2D). Microscopic examination confirmed that the delivery of PNPs was specifically restricted to cancer cells and not to the adjacent normal urothelial cells (Fig. 2E upper panels) or normal bladder (Fig. 2E lower panels).

Cytotoxicity and mechanisms of PNP-mediated photodynamic therapy against bladder cancer cells

We then determined the potential of PNPs for photodynamic therapy compared with 5-ALA, a traditional photosensitizer pro-drug. 5-ALA has been used for photodynamic therapy, but is not cancer-specific and requires an extensive incubation time (usually overnight to a few days) to metabolize into active photosensitizers. After illumination, PNPs caused concentration-dependent and light dose-dependent cytotoxicity against human bladder cancer cells even with only 2 hours of incubation (Fig. 3A left panel), and was >100 times more potent compared to 5-ALA in vitro (Fig. 3A right panel). After light exposure, PNP-pretreated bladder cancer cells showed dramatic cellular damage, as evidenced by cellular and nuclear swelling, loss of cell-cell contact, and degradation of the membrane (Fig. 3B). Consistent with decreased cell viability, intracellular ROS was increased (Fig. 3C) and glutathione decreased (Fig. 3D) for cells treated with PNPs plus light.

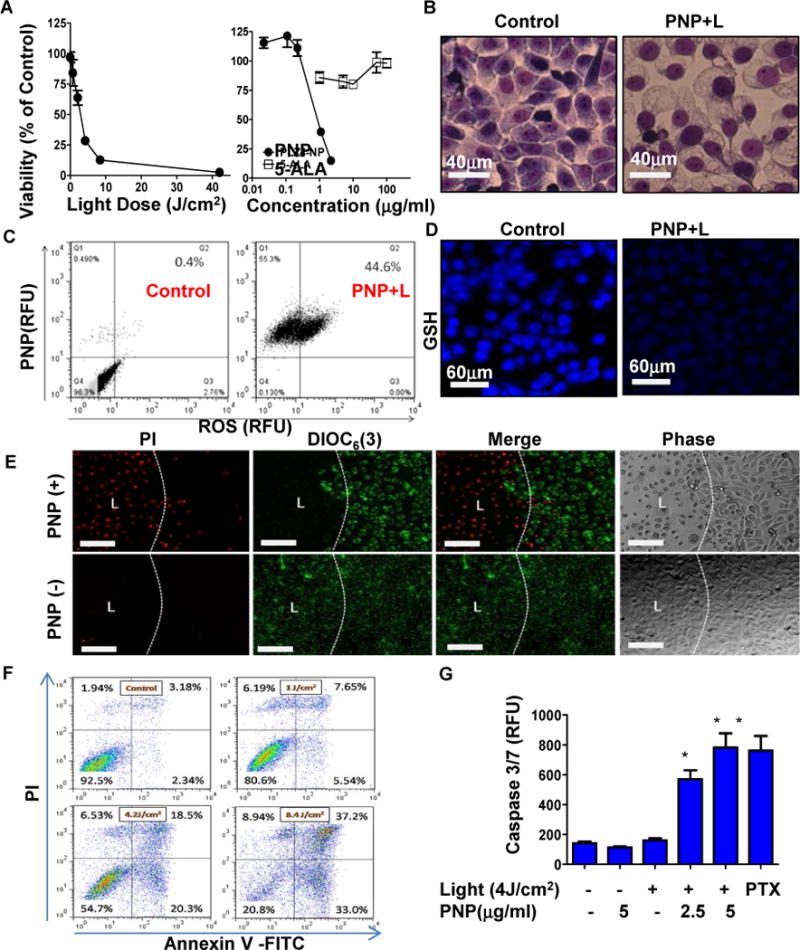

Figure 3. In vitro antitumor efficacy and cytotoxic mechanisms of PNPs against bladder cancer cells.

(A) left: the viability of 5637 bladder cancer cells at 24 hours post PNP treatment and illumination with different doses of light (Pyropheophorbide a: 2 μg/ml for 2 hours) and different PNP and 5-ALA concentrations (right) (Light dose: 4.2 J/cm2). (B) Cell morphology changes at 3 hours post PNP-mediated photodynamic therapy. (Hema3™, 1000× oil). (C) Intracellular ROS production and (D) Glutathione (GSH) levels in 5637 cells upon photodynamic therapy. (E) Mitochondria membrane potential (DiOC6(3): green) and cell integrity/viability (PI : red) 24 hours post treatment. Cells were incubated with DiOC6(3) and PI for 20 minute. DiOC6(3) low referred to loss of membrane potential, while PI + (red) stained dead cell nucleus. Bar=150 μm. (F) Apoptosis/necrosis assay, and (G) caspase 3/7 activation of 5637 cells at 24 hours post photodynamic therapy. PTX (1μg/ml) treated groups were served as positive control. (PI+/Annexvin V+ : late apoptosis; PI-/Annexvin V+: early apoptosis; PI+/Annexvin V− : Necrosis). (n=3, t-test, * p<0.05).

Moreover, after incubation with PNPs and light treatment at the left side of upper panels of Fig. 3E, cell integrity (assayed with positive PI staining (red fluorescence)), and mitochondrial potential (assayed with DiOC6(3) staining (DiOC6(3)low/PIhigh)) were lost within 24 hours. In contrast, cells treated with PNPs only without light (right half of Fig. 3E upper panels), light only without PNPs (left half of Fig. 3E lower panels) or no treatment (right half of Fig. 3E lower panels) remained alive with retention of mitochondrial potential and cell integrity (DiOC6(3)high/PIlow). Based on the apoptosis analysis, PNP-mediated photodynamic therapy caused bladder cancer cell apoptosis (Annexin V+/PI− and Annexin V+/PI+), necrosis (Annexin V−/PI+) (Fig. 3F), and caspase 3/7 activation (Fig. 3G), in a dose dependent manner. This supported the hypothesis that caspase3/7 mediated apoptosis presumably by ROS during photodynamic therapy.

In vivo photodynamic therapy in orthotopic PDX bladder cancer model

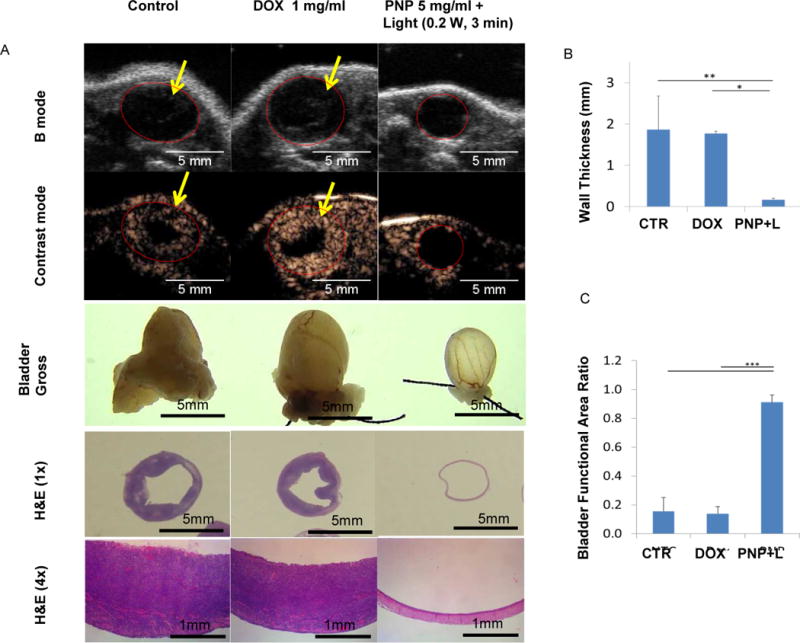

Next, we determined whether photodynamic therapy with PNPs could eliminate bladder cancer in an orthotopic bladder cancer PDX model. In 4 weeks post last light treatment, mice were examined with B-mode ultrasound and microbubble-enhanced contrast ultrasound imaging. Intravesical treatment with DOX has been clinically used to manage superficial bladder cancer[32] and thus was used as a chemotherapeutic treatment control. Mice in the PBS and DOX treated groups had significantly thicker tumor-filled bladder walls (Fig. 4A and B, Movie S1, S2, and S3) and significant lower ratio of functional bladder area (urine containing central areas/whole bladder (red circle)) (Fig. 4A and C). Of note, compared to B-mode, microbubble imaging improved bladder tumor visualization. Consistent with the ultrasound finding, bladders from PBS and DOX groups were enlarged and grossly and microscopically filled with solid bladder tumors, while the PNP treated group had a grossly normal bladder (Fig. 4A). Four of five (80%) in each of the PBS and DOX groups developed bladder cancer, while only one in four (25%) of the PNP group developed a small tumor. In summary, intravesical treatment of DOX was ineffective; however, PNP mediated PDT effectively prevented bladder cancer development in this orthotopic PDX mouse model.

Figure 4. Anti-bladder cancer efficacy study of PNPs and PNP-DOX in an orthotopic PDX mouse model.

(A) B-mode and microbubble enhanced ultrasound images, gross, and histopathology of mice carrying orthotopic PDX bladder cancer after treatments. Mice were implanted with BL645 inside bladder after pre-conditioned with acid. Mice were treated with PBS control, 1 mg/ml free DOX, or 5 mg/ml PNPs (1 mg/ml pyropheophorbide a) for 1 hour. After wash, PNP groups were further received whole bladder illumination (0.2 W for 3 minutes) via optical fiber. One month later, mice were imaged with ultrasound, and B-mode and contrast enhanced images were collected before and after microbubble injection to facilitate bladder cancer evaluation. After imaging, mice were sacrificed. Bladders were pre-filled with formalin (gross) before removal and submitted for histopathology evaluation (H&E stain, 1× and 4×). (B) The comparison of the wall thickness and (C) bladder functional area ratio of PDX bearing mice after treatment (n=3, one-way ANOVA tests, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***P<0.001).

Potential Synergistic effect of chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy in bladder cancer cells

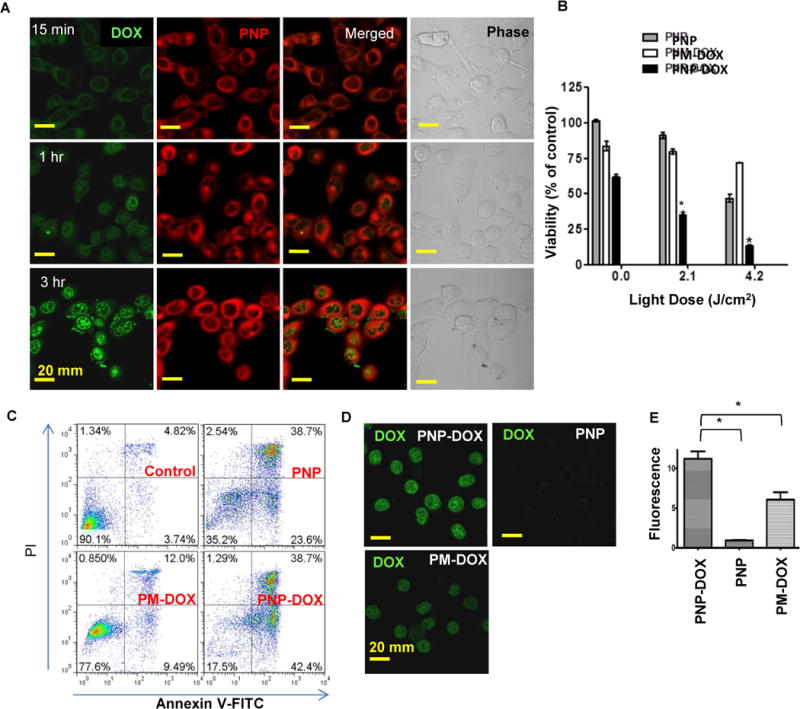

We studied the benefit of using PNPs as nanocarriers for cancer-specific targeted delivery of DOX for combination therapy. After treatment with PNP loaded with DOX (PNP-DOX) for 15 minutes, both PNPs and DOX signals accumulated and remained in the cytoplasm of 5637 human bladder cancer cells (Fig. 5A top panels). DOX kills cells through intercalating into DNA helix, and the DOX signal gradually increased in the nucleus from 1 to 3 hours after incubation, while PNPs remained in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). These results showed the ability of PNPs to deliver DOX into cells and subsequently release DOX into nucleus. Both PNPs and PNP-DOX showed light dose-dependent cytotoxicity, while light had a small effect on cell viability after treatment with DOX loaded PLZ4-micelles without porphyrin (PM-DOX) (Fig. 5B). This result was consistent with the apoptosis assay, which showed that 81.1% of PNP-DOX treated cells underwent apoptosis (Annexin V+), compared to 62.3% and 21.5% of PNPs and PM-DOX treated cells after light treatment (Fig. 5C). Together, this suggests a potential synergistic effect of chemotherapy from DOX and photodynamic therapy from PNPs with light illumination. Interestingly, even without light exposure, PNP-DOX decreased cell viability more than PNPs or PM-DOX at the same concentration. Consistent with this finding, PNP-DOX delivered significantly higher amounts of DOX into the nucleus compared to PM-DOX at the same concentration (Fig. 5 D & E).

Figure 5. Intracellular delivery of DOX and potential synergistic cytotoxic effect of PNP-DOX against bladder cancer cells.

(A) Subcellular distribution of PNP-DOX at 15 minutes, 1 and 3 hours after treatment. (DOX: green; PNPs: red) (630×, oil). (B) Viability assay on 5637 cells treated with PNPs, PM-DOX, and PNP-DOX for 2 hours followed by different light exposure. (n=3, t-test, * p<0.05). (C) Apoptosis assay on 5637 cells treated with PNPs, PM-DOX, and PNP-DOX for 2 hours followed by light exposure. (D) Intra-nucleus DOX fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscope after 2 hour incubation, and (E) quantitative imaging analysis of intranuclear DOX was performed using Image J. (n=3, t-test, * p<0.05)

Cancer-specific delivery of drug load in PDX bladder cancer models

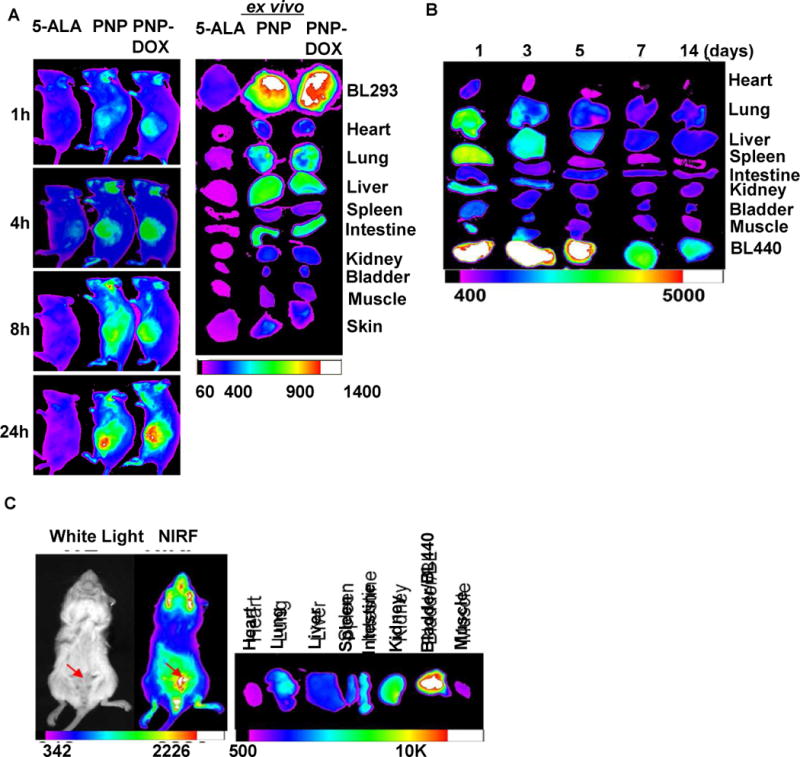

In addition to intravesical application, we then determined the possible of using PNPs in detection of and drug delivery with systemic administration. We first compared in vivo drug delivery of PNPs, PNP-DOX and free 5-ALA to subcutaneous xenografts after intravenous administration. The fluorescence signal from both the PNPs and PNP-DOX group showed time-dependent accumulation in xenografts as early as 4 hours, increasing to 24 hours (Fig. 6A), and retained in xenografts for up to two weeks (Fig. 6B). Minimal fluorescence was seen at the tumor site in mice treated with free 5-ALA (Fig. 6A). Ex vivo imaging confirmed the high selectivity and efficiency in the accumulation of PNPs and PNP-DOX in tumors when compared to free 5-ALA (Fig. 6A). Microscopic evaluation confirmed that the porphyrin signal (red) was primarily located in the perivascular area 24 hours post-injection (Fig. S6). Similar bladder cancer accumulation of PNP was also confirmed in the orthotopic BL440 patient-derived xenograft model, as fluorescence was greatest in the bladder tumors as compared to other organs (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. NIRF imaging of PDX mice models bearing subcutaneous and orthotopic bladder cancer.

(A) In vivo NIFR imaging of NSG mice bearing subcutaneous PDX BL293 up to 24 hours after intravenously administration of 5-ALA (100 mg/kg), PNPs (Pyropheophorbide a 5 mg/kg), and PNP-DOX (Pyropheophorbide a 5mg/kg and DOX 2.5 mg/kg). Right: ex vivo NIFR imaging for BL293 tumors and other major organs. (5-ALA induced protoporphyrin IX ex/em = 633/650–710nm; PNP ex/em = 680/690nm. Kodak imaging system 650/700nm) (B) Biodistribution and tumor retention of PNP-DOX at different time points after injection. (C) The NIRF imaging of mice bearing orthotopic BL440 PDX model (red arrow) 24 hours after the administration of PNP. (Left panel: In vivo whole mouse imaging; Right panel: ex vivo imaging)

In vivo photodynamic, photothermal and chemotherapy in PDX bladder cancer models

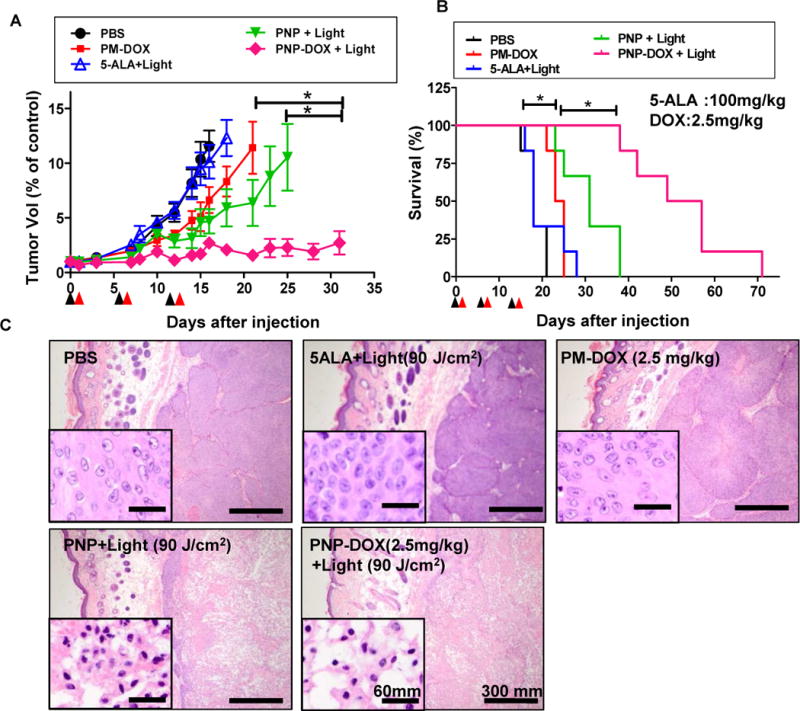

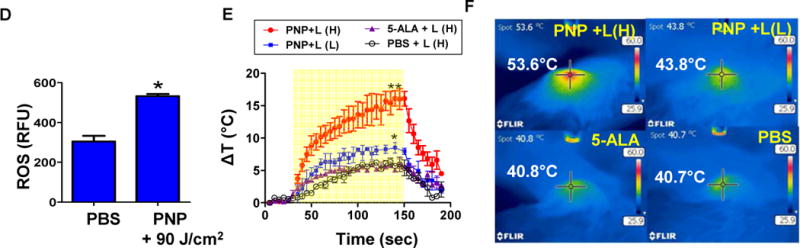

We further investigated whether this image-guided trimodal therapy (photodynamic therapy/photothermal therapy/targeted chemotherapy) of PNP-DOX could be translated into improved survival in PDX models. 5-ALA was currently approved photosensitizer and served as control, while free Pyropheophorbide a has extremely poor water solubility and thus was not optimal for in vivo study. Consistent with our prior finding[19], anti-cancer efficacy of PNPs was light dose dependent (Fig. S7). At the light dose of 90 J/cm2, the group treated with PNP-DOX with light showed prolonged inhibition of tumor growth compared with the control, 5-ALA, PM-DOX, and PNPs with light groups with the medium survival of 53 versus 18, 18, 24 and 31 days, respectively (p<0.05) (Fig. 7A&B and Table S2). The majority of tumors in the PNP-DOX group were eliminated after 3 treatments. Both PM-DOX and PNP with light treatment (90 J/cm2) showed significant delay in tumor progression and prolonged survival time compared to the PBS control and 5-ALA treated group with a medium survival of 24 and 31 days versus 18 and 18 days, respectively (p<0.05) (Fig. 7A&B and Table S2). No obvious body weight changes or other signs of toxicity were observed in all treatment groups. Microscopic evaluation showed that PNPs or PNP-DOX mediated phototherapy caused extreme tumor microenviroment damage and abundant tumor cell death/apoptosis evidenced by massive cellular dissociation, shrinking, cytoplasmic swelling, nucleus condensation and fragmentation (Fig. 7C), but not other groups. These in vivo results were in agreement with our in vitro studies that PNP-DOX mediated phototherapy showed potential synergistic anti-cancer effect with chemotherapy (Fig. 5B&C).

Figure 7. In vivo efficacy study of PNPs and PNP-DOX in PDX mouse model.

(A) The tumor volume changes and (B) survival curve of mice bearing subcutaneous PDX BL293 tumor after treatment. Black arrows: intravenous injection; red arrows: light treatment (90 J/cm2, 690 nm) (n=6). Tumors larger than 1000 mm3 were considered as end-point. Graph ended when one mouse in each group reached its end point. (*p<0.05, One-way ANOVA). (C) Histopathology evaluation of BL293 tumors at 24 hours post illumination. H&E stain, bar = 300 μm; insert: bar = 60 μm). (D) Intratumoral ROS production in mice bearing BL293 tumors after PNPs and PBS (control) followed by light exposure 90 J/cm2). (n=5, t-test, * p<0.01) (E) Time course of tumor temperatures before and after laser irradiation. Light dose low(L) (90 J/cm2) and high dose (H) (180 J/cm2). (yellow area: lights on; n=3, t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01) (F) Representative tumor surface temperature captured in the central spot by FLIR thermal camera.

To further elucidate the superior in vivo anti-cancer effect of PNPs, we compared the ROS and heat production at tumor site 24 hours after the administration of PNPs under light irradiation. PNP treated group produced significantly more ROS than the PBS group (p<0.01, Fig. 7D) upon illumination. Moreover, tumors in mice treated with PNPs showed light dose dependent temperature increase (ΔT=9°C at low light dose of 90 J/cm2, p=0.036 & 17 °C at the high light dose of 180 J/cm2, p=0.001) for photothermal therapy, while those mice treated with 5-ALA or PBS had much less temperature elevation (< 6°C) even after a high light exposure (Fig. 7E&F). PNP mediated photothermal therapy with high dose light could reach over 50 °C which was enough for thermal ablation of tumor alone (Fig. 7E&S7).

Discussion

Here we present the preclinical studies and proof of principle for innovative bladder cancer-specific targeting multifunctional PLZ4-nanoporphyrin (PNP) platform. This single PNP platform can be used simultaneously for photodynamic diagnosis and imaging-guided trimodal therapy. All of those applications can be achieved with this single PNP platform in a single procedure with a single wavelength of light with either intravesical or systemic administration. We validated these applications in patient-derived bladder cancer xenografts and believe the PNP platform have broad clinical applications and can be easily translated.

The PNP platform described here is a significant innovation over other photosensitizer and nanotheranostics. Traditional photosensitizers, such as 5-ALA and hexaminolevulinate, have poor selectivity between cancerous and non-cancerous tissues and unwanted skin accumulation that result in photo-toxicity and limited clinical applicability. To circumvent these limitations, several groups have encapsulated porphyrin analogs or other photosensitizers into nano-carriers, or conjugated them to a peptide or antibody for targeted delivery. For instance, pyropheophorbide a methyl ester and other porphyrin analogs were formulated into liposome [33], carbon nanotubes [34], or porphysome [35, 36]. Their relatively larger size (~100nm) may potentially limit delivery to tumor sites as enhanced permeability and retention effect is more significant with small nanoparticles (<100 nm), and we previously showed small micelles had better tumor delivery and penetration than large ones[23, 37]. PNPs are small in diameter (<25 nm), highly water soluble, possess preferential tumor accumulation, long retention at tumor site (up to 14 days), and low uptake in other normal tissues including skin as revealed by optical imaging (Fig. 6A&B). Long-term tumor accumulation suggested a long post-injection window for imaging detection and photothermal/photodynamic therapy which may allow a more flexible schedule for patients. Moreover, whole bladder illumination after PNP-DOX imaging-guided surgery or for treating diffuse cancer in situ will further clean out the non-visible and unresectable lesions and thus prevent recurrence. As shown in Fig. 4, photodynamic therapy eradicated cancer cell implants in the entire bladder without visualization. All these findings suggest that PNPs can potentially have great applications in monitoring drug delivery in real-time and identifying cancer cells that can guide tumor resection during cystoscopy, detecting cancer cells during follow-up cystoscopies to early diagnose cancer recurrence, and combining photodynamic diagnosis and therapy in a single procedure.

This novel PNP platform can potentially address several major clinical issues encountered in the diagnosis and treatment of non-myoinvasive bladder cancers [38–40]. Photodynamic diagnosis with fluorescence cystoscopy using 5-ALA or hexaminolevulinate could detect more cancer lesions and prolong recurrence free survival [41, 42], while some other trials showed no benefit at all [43]. One major reason for this limited efficacy is that it relies on relative metabolism and accumulation of photosensitizer metabolites in cancer cells over normal cells resulting in only 2–3 time difference between cancerous and non-cancerous cells [44]. In this study, we showed that PNPs did not bind to normal urothelial cells in mixture with cancer cells (Fig. 1H), and adjacent normal urothelial cells after intravesical instillation (Fig. 2). The difference of fluorescence between normal urothelial cells and cancer cells reached 30–50 times (Fig. 2D).

The superior antitumor efficacy of PNPs could be attributed to the integration of three therapeutic modalities (PDT/PTT/Chemo) in one nanoformulation, and the unique characteristics of the nano-platform. The combination therapy has been demonstrated to be more efficacious than single treatment alone in vitro and in vivo. PNP-DOX had prolonged DOX circulation time evidenced with a 10.6 times of AUC, compared to the free drug. Additionally, PTT might boost the “super EPR effect[45]” and PDT-induced vascular permeability effect [46], allowing long circulating PNP-DOX to further accumulate in the tumors. PTT induced heat and light treatment also trigger DOX release[19], collectively contributing to the superior anti-cancer effects[19]. Interestingly, the Lovell group also recently developed a long-circulating light-activated liposomal Dox and documented light-triggered drug release in the mouse cancer model [47]. We previously showed light induced DOX release from nanoporphyrin in vitro[19]. The PNPs described here have all the advantages described by Lovel et. al. In addition, the PNPs are multi-functional and have a bladder cancer-specific ligand PLZ4 on the surface that can prevent back flow of PNP into blood circulation.

Interestingly, Zhen et al reported another photosensitizer, ZnF16Pc loaded RGD-modified ferritin (RFRT) which exhibited strong affinity toward integrin αvβ3 on neoplastic endothelial cells. Upon RFRT mediated PDT, endothelial gaps increased resulting in superior vascular permeability and massive nanoparticle accumulation[48, 49]. Given that PLZ4 also interacts with integrin αvβ3, it would be interesting to explore the potential similar vascular effects through PLZ4-tumor endothelial cell interaction. Additionally, another relevant photosensitizer 3-(1′-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH) is current in clinical trials for non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma and early stage cancer of the larynx [50, 51] and was previously reported to have 100% tumor response in xenograft mice bladder cancer model at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg. In our study, we used 5 mg pyropheophorbide a /kg, which was chosen to match polymer concentration used to achieve the therapeutic DOX dose (2.5 mg/kg) in mice with our standard formulation (1 mg DOX/10 mg PNP or 2 mg pyropheophorbide a /ml). A more detailed dose-finding study is ongoing to determine the minimal dose required for effective PNP mediated phototherapy.

In conclusion, PNPs represent the first nano-theranostic system that could be utilized for imaging detection/guidance, photodynamic therapy, photothermal therapy, targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic agents and the combination of these therapies against bladder cancer. This PNP platform could be easily translated into clinical applications with minimal concern of toxicity and may dramatically improve the management for bladder cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks for Lisa Even, Sarah Tam, and Dr. Holly Marciniak Thompson for their assistance on ultrasound study on orthotopic model in mice.

Funding: This project was supported by the DoD PRMRP Award (PI: Lam, PR121626), Cancer Center Support Grant (PI: de Vere White, Grant P30 CA093373), and R01 (PI: Li, Grant # 1R01CA199668-01). Also, this work was supported in part by Merit Review (Award # I01 BX001784; PI: Pan), from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Program. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: T. Lin. and Y.L. conceived the idea and designed the overall experiments. Y. L. and J.C. synthesized and characterized the PNPs. T.Lin., Q. L., D.L., H. Z. and S.W.H. performed optical imaging and therapeutic studies on cells and animals. H.Z., K. F. performed the ultrasound imaging experiments. S.A. provided bladder PDX samples. T. Lin., Y.L. and C.P. wrote the paper and all authors commented on the manuscript. T.L., C.P., and K.S.L. supervised all the studies described in this report.

Potential conflicts of interest : T. Lin, Y.L, K.S.L. and C.P. are the inventors of a pending patent on nanoporphyrin (US patent application US76916-856975/212300). H. Z., K.S.L. and C.P. are the inventors of PLZ4 (US Patent application No.: 13/497,041). K.S.L. and C.P. are co-founder of LP Therapeutics Inc that has licensed the PLZ4 patent from University of California Davis.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herr HW. Restaging transurethral resection of high risk superficial bladder cancer improves the initial response to bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy. The Journal of urology. 2005;174:2134–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181799.81119.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamie K, Litwin MS, Bassett JC, Daskivich TJ, Lai J, Hanley JM, et al. Recurrence of high-risk bladder cancer: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2013;119:3219–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Redaelli A, Laskin B, Hauser R. The health economics of bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the published literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2003;21:1315–30. doi: 10.1007/BF03262330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray ER, Chatterton K, Thomas K, Khan MS, Chandra A, O’Brien TS. Hexylaminolevulinate photodynamic diagnosis for multifocal recurrent nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Journal of endourology/Endourological Society. 2009;23:983–8. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kausch I, Sommerauer M, Montorsi F, Stenzl A, Jacqmin D, Jichlinski P, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and cumulative analysis of prospective studies. Eur Urol. 2010;57:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, Schmidbauer J, Hermann G, Dragoescu O, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: a meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. Eur Urol. 2013;64:846–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manyak MJ, Ogan K. Photodynamic therapy for refractory superficial bladder cancer: long-term clinical outcomes of single treatment using intravesical diffusion medium. Journal of endourology/Endourological Society. 2003;17:633–9. doi: 10.1089/089277903322518644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61:250–81. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariappan P, Rai B, El-Mokadem I, Anderson CH, Lee H, Stewart S, et al. Real-life Experience: Early Recurrence With Hexvix Photodynamic Diagnosis-assisted Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour vs Good-quality White Light TURBT in New Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Urology. 2015;86:327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lykke MR, Nielsen TK, Ebbensgaard NA, Zieger K. Reducing recurrence in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer using photodynamic diagnosis and immediate post-transurethral resection of the bladder chemoprophylaxis. Scandinavian journal of urology. 2015;49:230–6. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2015.1019562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue K, Fukuhara H, Shimamoto T, Kamada M, Iiyama T, Miyamura M, et al. Comparison between intravesical and oral administration of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the clinical benefit of photodynamic diagnosis for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1062–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mowatt G, N’Dow J, Vale L, Nabi G, Boachie C, Cook JA, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of bladder cancer compared with white light cystoscopy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of technology assessment in health care. 2011;27:3–10. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin WWL, Lau WKO, Heng PWS, Bhuvaneswari R, Olivo M. Fluorescence imaging and phototoxicity effects of new formulation of chlorin e6-polyvinylpyrrolidone. J Photoch Photobio B. 2006;84:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellnier DA, Henderson BW, Pandey RK, Potter WR, Dougherty TJ. Murine Pharmacokinetics and Antitumor Efficacy of the Photodynamic Sensitizer 2-[1-Hexyloxyethyl]-2-Devinyl Pyropheophorbide-A. J Photoch Photobio B. 1993;20:55–61. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(93)80131-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Anai S, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y, Furuse H, Kai F, et al. Oral 5-aminolevulinic acid mediated photodynamic diagnosis using fluorescence cystoscopy for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A randomized, double-blind, multicentre phase II/III study. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy. 2015;12:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballut S, Makky A, Loock B, Michel JP, Maillard P, Rosilio V. New strategy for targeting of photosensitizers. Synthesis of glycodendrimeric phenylporphyrins, incorporation into a liposome membrane and interaction with a specific lectin. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009:224–6. doi: 10.1039/b816128c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Lin T-y, Luo Y, Liu Q, Xiao W, Guo W, et al. A smart and versatile theranostic nanomedicine platform based on nanoporphyrin. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Aina OH, Lam KS, de Vere White R, Evans C, Henderson P, et al. Identification of a bladder cancer-specific ligand using a combinatorial chemistry approach. Urol Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin TY, Zhang H, Wang S, Xie L, Li B, Rodriguez CO, Jr, et al. Targeting canine bladder transitional cell carcinoma with a human bladder cancer-specific ligand. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin TY, Li YP, Zhang H, Luo J, Goodwin N, Gao T, et al. Tumor-targeting multifunctional micelles for imaging and chemotherapy of advanced bladder cancer. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:1239–51. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo J, Xiao K, Li Y, Lee JS, Shi L, Tan YH, et al. Well-defined, size-tunable, multifunctional micelles for efficient paclitaxel delivery for cancer treatment. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2010;21:1216–24. doi: 10.1021/bc1000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng LLR, Marik J, Wang X, Takada Y, Lam KS. Combinatorial Chemistry Identifies High-Affinity Peptidomimetics against alpha4 beta1 Integrin. Nature Chemical Biology. 2006;2:381–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao W, Wang Y, Lau EY, Luo J, Yao N, Shi C, et al. The use of one-bead one-compound combinatorial library technology to discover high-affinity alphavbeta3 integrin and cancer targeting arginine-glycine-aspartic acid ligands with a built-in handle. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2714–23. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostaci RV, Damiron D, Grohens Y, Leger L, Drockenmuller E. Click chemistry grafting of poly(ethylene glycol) brushes to alkyne-functionalized pseudobrushes. Langmuir. 2010;26:1304–10. doi: 10.1021/la902482q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao K, Li Y, Lee JS, Gonik AM, Dong T, Fung G, et al. “OA02” peptide facilitates the precise targeting of paclitaxel-loaded micellar nanoparticles to ovarian cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2100–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin TY, Zhang H, Luo J, Li Y, Gao T, Lara PN, Jr, et al. Multifunctional targeting micelle nanocarriers with both imaging and therapeutic potential for bladder cancer. International journal of nanomedicine. 2012;7:2793–804. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao K, Li Y, Luo J, Lee JS, Xiao W, Gonik AM, et al. The effect of surface charge on in vivo biodistribution of PEG-oligocholic acid based micellar nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3435–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang XH, Ren LS, Wang GP, Zhao LL, Zhang H, Mi ZG, et al. A new method of establishing orthotopic bladder transplantable tumor in mice. Cancer biology & medicine. 2012;9:261–5. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan CX, Zhang H, Tepper CG, Lin TY, Davis RR, Keck J, et al. Development and Characterization of Bladder Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts for Molecularly Guided Targeted Therapy. PloS one. 2015;10:e0134346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nargund VH, Tanabalan CK, Kabir MN. Management of non-muscle-invasive (superficial) bladder cancer. Seminars in oncology. 2012;39:559–72. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guelluy PH, Fontaine-Aupart MP, Grammenos A, Lecart S, Piette J, Hoebeke M. Optimizing photodynamic therapy by liposomal formulation of the photosensitizer pyropheophorbide-a methyl ester: in vitro and ex vivo comparative biophysical investigations in a colon carcinoma cell line. Photochemical & photobiological sciences: Official journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology. 2010;9:1252–60. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00100g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu Y, Liu C, Nadiminty N, Lou W, Tummala R, Evans CP, et al. Inhibition of ABCB1 expression overcomes acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1829–36. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, et al. Porphysome nanovesicles generated by porphyrin bilayers for use as multimodal biophotonic contrast agents. Nature materials. 2011;10:324–32. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin CS, Cui L, Wang F, Chen J, Zheng G. Targeting-Triggered Porphysome Nanostructure Disruption for Activatable Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced healthcare materials. 2014 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Xiao K, Luo J, Lee J, Pan S, Lam KS. A novel size-tunable nanocarrier system for targeted anticancer drug delivery. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2010;144:314–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waters WB, Herbster G, Jablokow VR, Reda DJ. Ureteral replacement using ileum in compromised renal function. The Journal of urology. 1989;141:432–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cookson MS, Herr HW, Zhang ZF, Soloway S, Sogani PC, Fair WR. The treated natural history of high risk superficial bladder cancer: 15-year outcome. The Journal of urology. 1997;158:62–7. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199707000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herr HW, Schwalb DM, Zhang ZF, Sogani PC, Fair WR, Whitmore WF, Jr, et al. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy prevents tumor progression and death from superficial bladder cancer: ten-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1995;13:1404–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colleselli D, Stenzl A, Schwentner C. Re: Florian Jentzmik, Carsten Stephan, Kurt Miller, et al. Sarcosine in urine after digital rectal examination fails as a marker in prostate cancer detection and identification of aggressive tumours. Eur Urol 2010;58:12–8. Eur Urol. 2010;58:e51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denzinger S, Burger M, Walter B, Knuechel R, Roessler W, Wieland WF, et al. Clinically relevant reduction in risk of recurrence of superficial bladder cancer using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence diagnosis: 8-year results of prospective randomized study. Urology. 2007;69:675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumacher MC, Holmang S, Davidsson T, Friedrich B, Pedersen J, Wiklund NP. Transurethral resection of non-muscle-invasive bladder transitional cell cancers with or without 5-aminolevulinic Acid under visible and fluorescent light: results of a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Eur Urol. 2010;57:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seidl J, Rauch J, Krieg RC, Appel S, Baumgartner R, Knuechel R. Optimization of differential photodynamic effectiveness between normal and tumor urothelial cells using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX as sensitizer. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2001;92:671–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<671::aid-ijc1240>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sano K, Nakajima T, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Markedly enhanced permeability and retention effects induced by photo-immunotherapy of tumors. ACS Nano. 2013;7:717–24. doi: 10.1021/nn305011p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snyder JW, Greco WR, Bellnier DA, Vaughan L, Henderson BW. Photodynamic therapy: a means to enhanced drug delivery to tumors. Cancer research. 2003;63:8126–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo D, Carter KA, Razi A, Geng J, Shao S, Giraldo D, et al. Doxorubicin encapsulated in stealth liposomes conferred with light-triggered drug release. Biomaterials. 2016;75:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhen Z, Tang W, Guo C, Chen H, Lin X, Liu G, et al. Ferritin nanocages to encapsulate and deliver photosensitizers for efficient photodynamic therapy against cancer. ACS nano. 2013;7:6988–96. doi: 10.1021/nn402199g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo D, Carter KA, Miranda D, Lovell JF. Chemophototherapy: An Emerging Treatment Option for Solid Tumors. Advanced Science. 2016:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/advs.201600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nava HR, Allamaneni SS, Dougherty TJ, Cooper MT, Tan W, Wilding G, et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) using HPPH for the treatment of precancerous lesions associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2011;43:705–12. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhillon SS, Demmy TL, Yendamuri S, Loewen G, Nwogu C, Cooper M, et al. A Phase I Study of Light Dose for Photodynamic Therapy Using 2-[1-Hexyloxyethyl]-2 Devinyl Pyropheophorbide-a for the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Carcinoma In Situ or Non-Small Cell Microinvasive Bronchogenic Carcinoma: A Dose Ranging Study. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016;11:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.