Abstract

Introduction

The omega-3 index represents the red blood cell (RBC) content of two major long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). We sought to determine factors associated with a favorable response to fish oil treatment as well as to characterize changes in RBC PUFAs associated with fish oil supplementation.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of the OMEGA-PAD I Trial, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial investigating short-duration, high-dose n-3 PUFA oral supplementation on endothelial function and inflammation in subjects with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Patients with mild to severe claudication received either 4.4g of fish oil providing 2.6g of EPA + 1.8g of DHA daily (n=40) or placebo capsules (n=40) for 1 month. The RBC fatty acid content was measured by gas chromatography and expressed as a percent of total fatty acids. The change in omega-3 index was calculated as the difference between pre- and post-supplementation in the fish oil and placebo groups. Univariate analysis identified predictors of change in omega-3 index, with these variables included in our multivariable model.

Results

In the fish oil group, there was an increase in the omega-3 index (5.1 ± 1.3% to 9.0 ± 1.8%; p<0.0001), whereas there was no change in the control group. Factors associated with a favorable response (i.e., greater than the median change of 4.06%) included a lower body mass index (BMI) and higher concentrations of low-density lipoproteins (LDL). Other demographic/lifestyle factors such as age, race, or smoking status were unrelated to the response. Oral n-3 PUFA supplementation also decreased the n-6 PUFA content in RBCs.

Conclusion

Short-term, high-dose n-3 PUFA supplementation increases the omega-3 index to a greater extent in patients with a lower BMI and higher total and LDL cholesterol levels.

Keywords: peripheral artery disease, fish oil, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, omega-3 index

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the vasculature, continues to be associated with a high risk of cardiovascular events and mortality compared to coronary artery disease (CAD), despite the wide availability of medical and interventional therapies (1). Current nutritional guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology recommend a diet rich in oily fish for individuals with cardiovascular disease, including peripheral arterial disease (PAD) (2). Evidence demonstrates that n-3 PUFA play a role in reducing systemic inflammation (3) and protecting against the development of atherosclerosis (4). A widely used biomarker of n-3 PUFA status is the omega-3 index, which represents the level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in red blood cell (RBC) membranes (5). This marker is a well-documented surrogate of the EPA+DHA status of other tissues (6–8). The omega-3 index is inversely associated with a high-risk CAD profile (9) and inflammatory markers (10), and has been proposed as an actual risk factor for death from CAD (5). Therefore, a relatively low membrane concentration of n-3 PUFA may contribute to the development and progression of PAD (11).

We have previously reported that in patients with PAD, a higher omega-3 index was associated with older age, elevated body mass index (BMI), and prior fish oil supplementation, while a history of smoking correlated with a lower omega-3 index (12). We also demonstrated the ability of high-dose, short duration n-3 PUFA supplementation to increase the omega-3 index in patients with PAD (13). Determining those factors involved in a robust response to n-3 PUFA supplementation could help guide treatment considerations in patients with PAD. The goal of this analysis was, therefore, to identify factors associated with a favorable response to fish oil treatment. We also aimed to characterize changes in other RBC fatty acids with n-3 PUFA supplementation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The methods of the OMEGA-PAD I (NCT01310270) Trial, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial designed to assess the impact of high-dose, short-term n-3 PUFA supplementation on endothelial function and inflammation in patients with symptomatic PAD, have been previously published (14). The current study is a secondary analysis utilizing data from that trial to investigate baseline omega-3 indices in PAD patients, absolute change in the omega-3 index after a one-month course of high-dose n-3 PUFA supplementation, and predictors of omega-3 index response. Eighty patients with stable, mild or severe claudication (Rutherford Class 1 to 3) received either 4.4g of fish oil capsules consisting of 2.6g of EPA and 1.8g of DHA daily (n=40) or placebo capsules (n=40) for 1 month. The placebo capsules were the same shape and color as the fish oil capsules, and the same quantity of capsules was taken daily by all participants in both cohorts. The omega-3 index was analyzed according to the HS-Omega-3 index® methodology (15).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the intervention and placebo groups were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and unpaired t-tests for continuous variables. Changes in RBC PUFA composition from pre- to post-intervention were compared within and between intervention groups using paired t-tests for within-group comparisons and unpaired t-tests for between group comparisons. Within only the intervention group, factors associated with a change in omega-3 were examined for two levels of response: 1) a difference greater than the median response, and 2) a difference greater than the 75th percentile response. We first used univariate logistic regression models to examine each characteristic for potential association with change in level of omega-3 index. We then constructed multivariable logistic regression models including predictors that were significant at the 0.05 level in univariate analysis and adjusted for age. The models were restricted to those subjects who were in the intervention group (n=40). When predictors were highly correlated with one another, we chose to include the predictor which yielded the highest c-statistic contributed the most information. An alpha-level of 0.05 was used to determine significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics and clinical profiles of the two intervention groups have been previously published (13) and are included in Table 1. The two groups were similar at baseline as all subjects were primarily male, Caucasian, and in their mid-sixties. The majority of their cardiovascular and PAD risk factors were also similar, with a history of CAD being the only exception. The fish oil cohort had 33% of patients with known CAD compared to 55% of patients in the placebo cohort (p=0.04).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Profile of the Study Population.

| General Characteristics | FISH (n=40) |

PLACEBO (n=40) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 ± 7 | 69 ± 9 | 0.41 |

| Male | 39 (98) | 39 (98) | 1.0 |

| Caucasian | 27 (68) | 31 (78) | 0.32 |

| BMI (kg/m) | 28 ± 5 | 27 ± 4 | 0.17 |

| Index ABI | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 0.74 |

| Rutherford | |||

| Mild Claudication | 10 (25) | 10 (25) | 0.75 |

| Moderate Claudication | 10 (25) | 12 (30) | |

| Severe Claudication | 20 (50) | 18 (45) | |

| Omega Index (%) | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 0.13 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Coronary Artery Disease | 13 (33) | 22 (55) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 38 (95) | 35 (88) | 0.24 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 32 (80) | 36 (90) | 0.21 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 11 (28) | 14 (35) | 0.47 |

| PAD Risk Factors | |||

| History of smoking | 38 (95) | 36 (90) | 0.40 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 175 ± 48 | 161 ± 37 | 0.15 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 157 ± 99 | 150 ± 69 | 0.71 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45 ± 14 | 44 ± 12 | 0.77 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 100 ± 42 | 87 ± 33 | 0.12 |

| Statin therapy | 31 (77.5%) | 37 (92.5%) | 0.12 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 6.1 ± 1.2 | 0.85 |

| Vitamin D (ng/ml) | 24 ± 11 | 23 ± 12 | 0.64 |

| Inflammation | |||

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 4.3 ± 4.6 | 4.2 ± 4.1 | 0.91 |

| IL – 6 (pg/ml) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.59 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/ml) | 250 ± 77 | 281 ± 101 | 0.13 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.05 |

| Fibrinogen | 389 ± 77 | 389 ± 105 | 0.99 |

ABI – ankle brachial index; HDL – high-density lipoprotein; LDL – low-density lipoprotein; HbA1c – Hemoglobin A1c; hsCRP – high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6 – interleukin-6; ICAM-1 - intercellular adhesion molecule 1; TNF- α –tumor necrosis factor - α

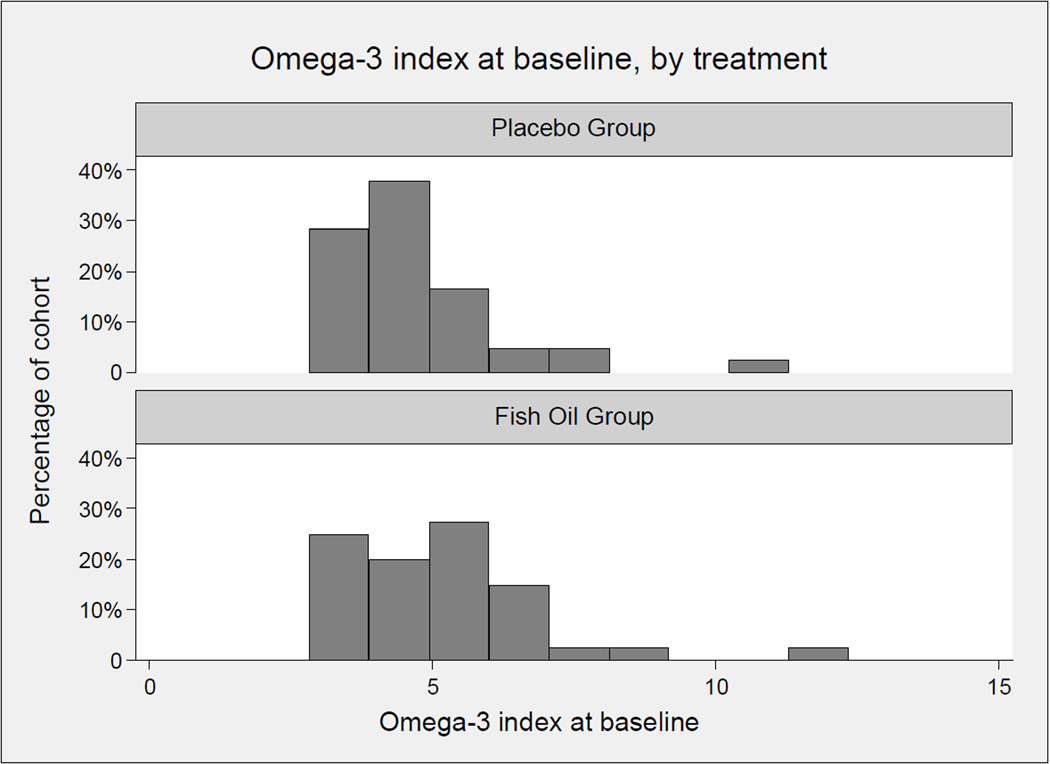

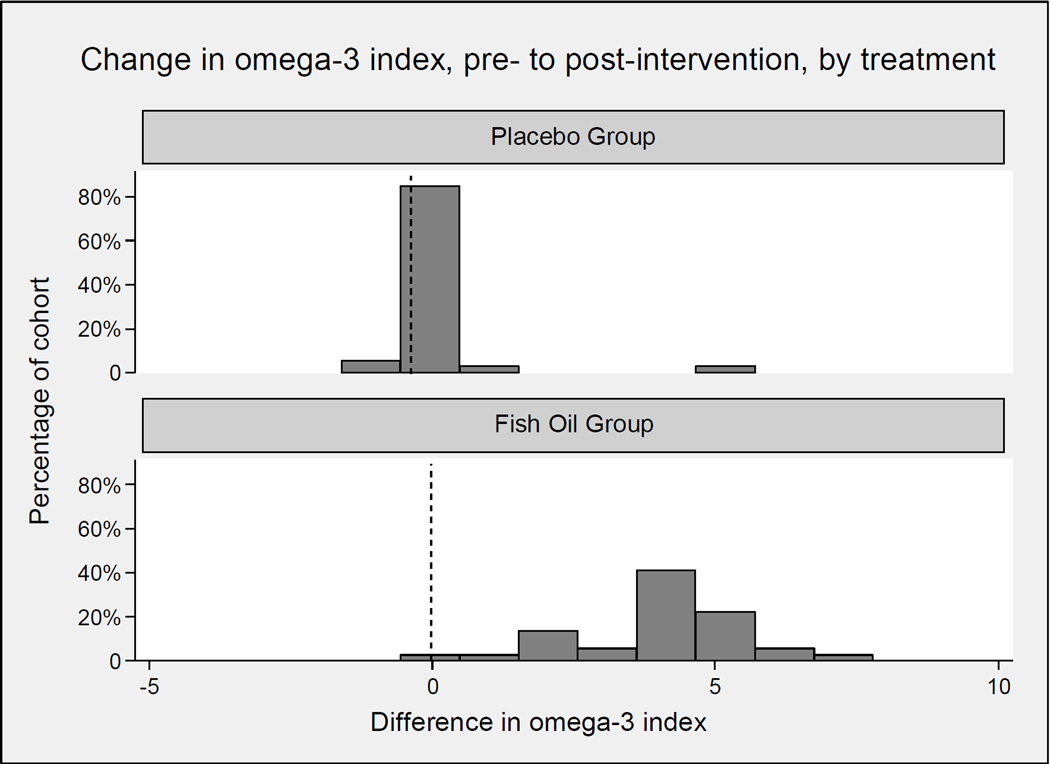

The baseline omega-3 index (Figure 1) averaged 5%, with a right-tail skew seen in both cohorts. Following one month of fish oil supplementation, the mean increase in the omega-3 index was 3.99 ± 1.4% (p<0.0001) in the supplemented fish oil group, while no change was seen in the control group (+0.11 ± 0.91, p=0.49) (Figure 2). The increase in the n-3 PUFAs was accompanied by a decrease in the n-6 PUFAs, as well as cis-monosaturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids (Table 2).

Figure 1. Baseline omega-3 index in patients with PAD.

Histogram of omega-3 index at baseline in placebo group (A) and fish oil group (B). The histograms show a similarly right-tailed distribution in the two groups.

Figure 2. Change in omega-3 index.

Following one month of fish oil supplementation, there was no change in the omega-3 index in the control group [4.8 ± 1.5% to 4.9 ± 1.4% (p=0.49)] (A). The mean omega-3 index increased significantly from 5.1 ± 1.3% to 9.0 ± 1.8% (p<0.0001) in the supplemented fish oil group.

Table 2.

Changes in red blood cell PUFA composition

| Fish oil group | Placebo group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Intervention -Pre-Intervention (n=40) |

Post-Intervention -Pre-Intervention (n=40) |

Between- group p-value |

|||||

| Name | mean | (sd) | p-value | mean | (sd) | p-value | |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (%) | |||||||

| Alpha-linolenic | −0.006 | (0.04) | 0.37 | −0.02 | (0.09) | 0.30 | 0.53 |

| Eicosapentaenoic | 2.17 | (0.78) | <0.0001 | 0.06 | (0.07) | 0.40 | <0.0001 |

| Docosapentaenoic | 0.57 | (0.27) | <0.0001 | 0.03 | (0.22) | 0.48 | <0.0001 |

| Docosahexaenoic | 1.82 | (0.81) | <0.0001 | 0.05 | (0.56) | 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| Omega-6 Fatty-Acids (%) | |||||||

| Linoleic | −0.98 | (1.47) | 0.0004 | 0.08 | (1.04) | 0.66 | 0.0009 |

| gamma-Linolenic | −0.03 | (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.006 | (0.03) | 0.29 | <0.0001 |

| Eicosadienoic | −0.02 | (0.04) | 0.008 | 0.02 | (0.02) | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| Dihomo-g-linolenic | −0.35 | (0.30) | <0.0001 | −0.06 | (0.21) | 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Arachidonic | −1.93 | (1.11) | <0.0001 | 0.12 | (0.79) | 0.39 | <0.0001 |

| Docosatetraenoic | −0.81 | (0.38) | <0.0001 | −0.02 | (0.33) | 0.69 | <0.0001 |

| Docosapentaenoic | −0.18 | (0.28) | 0.0006 | 0.009 | (0.23) | 0.82 | 0.003 |

| Cis-Monosaturated Fatty Acids (%) | |||||||

| Palmitoleic | −4.56 | (0.83) | <0.0001 | −4.37 | (0.94) | <0.0001 | 0.38 |

| Oleic | 0.35 | (0.55) | 0.0006 | −0.26 | (0.66) | 0.03 | 0.51 |

| Eicosenoic | −0.01 | (0.04) | 0.10 | −0.004 | (0.03) | 0.48 | 0.40 |

| Nervonic | 0.12 | (0.24) | 0.004 | 0.06 | (0.19) | 0.07 | 0.22 |

| Saturated Fatty Acids (%) | |||||||

| Myristic | −0.04 | (0.08) | 0.004 | 0.01 | (0.09) | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| Palmitic | −0.08 | (0.76) | 0.56 | −0.19 | (0.88) | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| Stearic | 0.08 | (0.50) | 0.34 | 0.04 | (0.56) | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| Arachidic | 0.02 | (0.03) | 0.006 | 0.01 | (0.03) | 0.02 | 0.71 |

| Behenic | 0.04 | (0.08) | 0.009 | 0.02 | (0.05) | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| Lignoceric | 0.13 | (0.27) | 0.006 | 0.07 | (0.18) | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| Trans Fatty Acids (%) | |||||||

| Palmitelaidic | −0.006 | (0.04) | 0.38 | −0.005 | (0.02) | 0.25 | 0.91 |

| Elaidic | −0.07 | (0.27) | 0.14 | −0.01 | (0.10) | 0.45 | 0.25 |

| Linoelaidic | −0.03 | (0.09) | 0.09 | 0.03 | (0.09) | 0.09 | 0.02 |

Table 3 identifies factors associated with a more (vs. less) robust response comparing those whose omega-3 index increased by more than the median response across all subjects (i.e., >4.06%) to those whose increase was less than the median. Table 3 also identifies factors associated with a more robust response comparing those whose omega-3 index increased by more than the 75th percentile to those whose increase fell below this level. Baseline levels of total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were directly associated with a more robust response, while BMI was inversely associated with such a response. For every 10 mg/dL higher the level of total and LDL cholesterol, the likelihood of an above-median change in omega-3 index increased by 25%, while for every one-unit greater the BMI, the likelihood of an abovemedian change in omega-3 index decreased by almost 20%. In multivariable analysis, LDL cholesterol (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.60) remained independently associated with an increased likelihood of an above-median change in the omega-3 index, and BMI (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.97) maintained an inverse relationship to an above-median response (Table 4). A Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test indicated a good fit for the model (p=0.35), which yielded a c-statistic (area under the ROC curve) of 0.83. Although age was not significant in univariate analysis, we adjusted for age in the multivariable model. Furthermore, omitting age also resulted in a slightly lower c-statistic (0.82). In this study, compliance (defined by pill count) was not significantly associated with omega-3 index response.

Table 3.

Factors associated with a strong response in omega-3 index in a univariate analysis

| Omega-3 index change above median |

Omega-3 index change above 75th percentile |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age (decades) | 0.93 | (0.39, 2.23) | 0.88 | 0.74 | (0.25, 2.16) | 0.58 |

| Caucasian | 1.20 | (0.29, 5.02) | 0.80 | 4.12 | (0.44, 38.5) | 0.22 |

| BMI at baseline | 0.81 | (0.67, 0.97) | 0.02 | 0.79 | (0.63, 0.995) | 0.05 |

| Blood pressure at baseline | ||||||

| SBP (10 units) | 0.67 | (0.42, 1.09) | 0.11 | 0.53 | (0.27, 1.06 | 0.07 |

| DBP (10 units) | 0.92 | (0.46, 1.83) | 0.81 | 1.06 | (0.47, 2.38) | 0.89 |

| Pill count | 0.99 | (0.97, 1.01) | 0.54 | 0.999 | (0.97, 1.02) | 0.94 |

| PAD risk factors at baseline | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.94 | (0.05, 16.3) | 0.97 | 0.27 | (0.01, 4.87) | 0.37 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.43 | (0.09, 2.09) | 0.30 | 0.34 | (0.04, 3.23) | 0.35 |

| History of smoking | 0.94 | (0.05, 16.3) | 0.97 | N/A | ||

| Tobacco use | 0.66 | (0.21, 2.03) | 0.47 | 0.83 | (0.23, 3.03) | 0.77 |

| Renal, lipid and metabolic measurements |

||||||

| Creatinine | 0.10 | (0.004, 2.67) | 0.17 | 0.007 | (0.00003, 1.57) | 0.07 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.06) | 0.22 | 1.05 | (0.999, 1.11) | 0.057 |

| Albumin | 1.22 | (0.12, 12.7) | 0.87 | 4.07 | (0.22, 74.9) | 0.35 |

| Hemoglobin A1C | 0.73 | (0.37, 1.46) | 0.37 | 0.46 | (0.14, 1.50) | 0.20 |

| Total cholesterol (10 mg/dL) | 1.24 | 1.04, 1.48) | 0.02 | 1.14 | (0.96, 1.35) | 0.13 |

| HDL cholesterol (10 mg/dL) | 1.48 | (0.76, 2.87) | 0.24 | 1.03 | 0.49, 2.15) | 0.94 |

| LDL cholesterol (10 mg/dL) | 1.26 | (1.03, 1.53) | 0.02 | 1.13 | (0.94, 1.36) | 0.20 |

| Triglycerides (10 units) | 1.01 | (0.92, 1.11) | 0.79 | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.17) | 0.29 |

| Homocysteine | 1.05 | (0.87, 1.27) | 0.58 | 0.46 | (0.14, 1.50) | 0.20 |

| Inflammatory marker | ||||||

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.98 | (0.86, 1.13) | 0.80 | 1.01 | (0.86, 1.18) | 0.92 |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Statin | 0.18 | (0.03, 1.04) | 0.06 | 0.48 | (0.09, 2.59) | 0.39 |

| Aspirin | 1.47 | (0.38, 5.72) | 0.58 | 2.40 | (0.41, 14.1) | 0.33 |

| Ace inhibitor | 1.10 | (0.89, 4.26) | 0.89 | 0.87 | (0.17, 4.43) | 0.87 |

| Beta blocker | 1.40 | (0.35, 5.54) | 0.63 | 1.02 | (0.20, 5.21) | 0.98 |

BMI – body mass index; SBP – systolic blood pressure; DBP – diastolic blood pressure; PAD – peripheral arterial disease; HDL – high-density lipoprotein; LDL – low-density lipoprotein; hsCRP – high sensitivity C-reactive protein

Table 4.

Factors Associated with a Positive Response to n-3 PUFA in a Multivariable Analysis.

| Multivariable Analysis: Factors associated with response above median | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 index change above median |

|||

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age, per year | 0.88 | (0.30, 2.60) | 0.82 |

| BMI at baseline, per kg/m2 | 0.78 | (0.62, 0.97) | 0.03 |

| LDL cholesterol (10 mg/dL) | 1.28 | (1.02, 1.60) | 0.03 |

BMI – body mass index; LDL – low-density lipoprotein. A Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test indicates a good fit for the model (p=0.35), and the c-statistic (area under the ROC curve) is 0.83.

DISCUSSION

A one month-long, high-dose fish oil intervention was found to increase the omega-3 index, increasing the total omega-3 fatty acids and decreasing the n-6 PUFA in the RBC membrane. A stronger response to n-3 PUFA was seen in those patients with lower BMI as well as those with higher LDL and total cholesterol.

PAD is associated with heightened systemic vascular inflammation (16) and elevated risk of cardiovascular events and mortality (1, 17). Endothelial dysfunction is believed to be an important contributing mechanism to the progression of atherosclerosis (18–20). n-3 PUFA supplementation has long been recognized to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, with current evidence suggesting that n-3 PUFA may improve both systemic inflammation and vascular function in patients with PAD (13, 21–23). The omega-3 index is a validated biomarker of n-3 PUFA status based on data demonstrating that the EPA + DHA content in RBC membranes provides an accurate estimate of overall n-3 PUFA intake (24). n-3 PUFAs derived from fish oil have been found to yield beneficial effects on cardiovascular health (25, 26), including decreasing mortality from cardiovascular causes, all-cause mortality, and non-fatal cardiovascular events (27–30). Our previous work has shown that predictors of higher omega-3 index in patients with PAD were older age, elevated BMI and prior fish oil supplementation (12). Here we investigated the predictors of a response to fish oil supplementation and found that a lower BMI and higher LDL cholesterol were the only independent predictors of a favorable response in the omega-3 index.

With respect to the effect seen in subjects with higher LDL levels, we believe this could be partially explained by increased circulating phosphotidylserine (PL)-esterified fatty acid levels. With fish oil supplementation, EPA and DHA are first incorporated into plasma lipids, especially PL (31), a large part of which are found in LDL. Subsequently, RBC membrane PLs may exchange with plasma PL (32). Therefore, increased response of RBC n-3 PUFA with fish oil supplementation may be secondary to the presence of increased circulating LDL, which are the reservoir of EPA and DHA prior to membrane incorporation. The better response in omega-3 index seen in those individuals with a lower BMI could be explained by the fact that the dose per kg body weight is higher in individuals with lower body weights. Therefore, clinical consideration could be given to providing a weight-based dosing schedule related to the patient’s BMI.

The factors identified in this study as predictors of a robust response to n-3 PUFA supplementation could help guide treatment considerations in patients with PAD. Guidelines from the American Heart Association recommend that individuals with cardiovascular disease incorporate fish into their diets and supplement daily with n-3 PUFA (33–35). Furthermore, there is evidence that a low omega-3 index, which varies with n-3 PUFA content in the diet, is predictive of sudden death (36). Our previous work identified a subset of patients with PAD with claudication who may benefit from n-3 PUFA supplementation (13). Screening with the omega-3 index may help identify a subgroup who may benefit from n-3 PUFA supplementation. More robust studies are, however, needed to address this question. Hence, although inclusion of the omega-3 index in our patients could provide important insight, we cannot make formal recommendations at this point.

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size drawn from a fairly specialized population. The cohort is primarily made up of Caucasian males, reflecting the patient population served by the San Francisco Veteran Affairs Medical Center; hence, this cohort may not be representative of the broader PAD population. Because our cohort was comprised of 98% males, our findings cannot be generalized to women with PAD. In addition, a history of smoking was almost universal in both groups (95% in the intervention group and 90% in the placebo group); because the two groups were essentially matched on this risk factor, we could not reliably examine its effect. Although it is possible that persistent smoking during the trial may have blunted the effects of omega-3 index response, we did not capture data on whether or not participants were current smokers. Another limitation relates to compliance with omega-3 daily supplementation. Pill count analysis suggests that compliance was good; however, it is possible that patients did not bring back their pills for the pill count, which would lead to falsely elevated compliance rates. Finally, findings of this study need to be interpreted as hypothesis-generating in light of the lack of a priori power analyses.

CONCLUSION

High-dose, short-term fish oil supplementation increased the omega-3 index and reduced n-6 PUFA content in RBCs. Predictors of a more robust omega-3 index response included a lower BMI and a higher LDL cholesterol level. We will continue to investigate the implications of the omega-3 index and changes in n-3 PUFA and n-6 PUFA RBC membrane content in patients with PAD in a follow-up trial (OMEGA-PAD II; NCT01979874).

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by start-up funds from the University of California San Francisco and the Northern California Institute for Research and Education. The project described was supported by Award Number KL2RR024130 from the National Center for Research Resources, Award Number 1K23HL122446-01 from the National Institute of Health/NHLBI, and a Society for Vascular Surgery Seed Grant and Career Development Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. The funding organizations were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. This publication was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number ULI TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors would also like to thank Nordic Naturals for donation of the treatment and placebo capsules.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: The study was designed and implemented by S.M. Grenon. Statistical analyses were conducted by N. Hills. W.S. Harris performed the fatty acid analysis. The manuscript was written by L.M. Drudi and M.S. Schaller, with expert contributions and critical revisions by all of the authors, each of whom has approved the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grenon SM, Vittinghoff E, Owens CD, Conte MS, Whooley M, et al. Peripheral artery disease and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease: insights from the Heart and Soul Study. Vasc Med. 2013;18:176–184. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13493825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, de Jesus JM, Houston Miller N, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S76–S99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437740.48606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madden J, Brunner A, Dastur ND, Tan RM, Nash GB, et al. Fish oil induced increase in walking distance, but not ankle brachial pressure index, in peripheral arterial disease is dependent on both body mass index and inflammatory genotype. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;76:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holy EW, Forestier M, Richter EK, Akhmedov A, Leiber F, et al. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid inhibits arterial thrombus formation, tissue factor expression, and platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1772–1780. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris WS. The omega-3 index as a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1997S–2002S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1997S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris WS, Sands SA, Windsor SL, Ali HA, Stevens TL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in cardiac biopsies from heart transplantation patients: correlation with erythrocytes and response to supplementation. Circulation. 2004;110:1645–1649. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142292.10048.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurzell EA, Wiesinger JA, Morkam C, Hemmrich S, Harris WS, et al. Is the omega-3 index a valid marker of intestinal membrane phospholipid EPA+DHA content? Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2014;91:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metcalf RG, Cleland LG, Gibson RA, Roberts-Thomson KC, Edwards JR, et al. Relation between blood and atrial fatty acids in patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:528–534. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WS, Pottala JV, Lacey SM, Vasan RS, Larson MG, et al. Clinical correlates and heritability of erythrocyte eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid content in the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontes JD, Rahman F, Lacey S, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Red blood cell fatty acids and biomarkers of inflammation: a cross-sectional study in a community-based cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2015;240:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonelli-Incalzi R, Pedone C, McDermott MM, Bandinelli S, Miniati B, et al. Association between nutrient intake and peripheral artery disease: results from the InCHIANTI study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosova EV, Chong KC, Alley HF, Harris WS, Boscardin WJ, et al. Clinical correlates of red blood cell omega-3 fatty acid content in male veterans with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1325–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grenon SM, Owens CD, Nosova EV, Hughes-Fulford M, Alley HF, et al. Short-Term, High-Dose Fish Oil Supplementation Increases the Production of Omega-3 Fatty Acid-Derived Mediators in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease (the OMEGA-PAD I Trial) J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002034. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grenon SM, Owens CD, Alley H, Chong K, Yen PK, et al. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in peripheral artery disease: the OMEGA-PAD trial. Vasc Med. 2013;18:263–274. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13503695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farzaneh-Far R, Lin J, Epel ES, Harris WS, Blackburn EH, et al. Association of marine omega-3 fatty acid levels with telomeric aging in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2010;303:250–257. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federman DG, Bravata DM, Kirsner RS. Peripheral arterial disease. A systemic disease extending beyond the affected extremity. Geriatrics. 2004;59:26, 29–30. 32 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rallidis LS, Varounis C, Sourides V, Charalampopoulos A, Kotakos C, et al. Mild depression versus C-reactive protein as a predictor of cardiovascular death: a three year follow-up of patients with stable coronary artery disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1407–1413. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.584061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH, Kim JW, Ko YH, Choi CU, Na JO, et al. Coronary endothelial dysfunction associated with a depressive mood in patients with atypical angina but angiographically normal coronary artery. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinen Y, Stegemann E, Sansone R, Benedens K, Wagstaff R, et al. Local association between endothelial dysfunction and intimal hyperplasia: relevance in peripheral artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botti C, Maione C, Dogliotti G, Russo P, Signoriello G, et al. Circulating cytokines present in the serum of peripheral arterial disease patients induce endothelial dysfunction. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He K, Liu K, Daviglus ML, Jenny NS, Mayer-Davis E, et al. Associations of dietary long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish with biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial activation (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1238–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micallef MA, Munro IA, Garg ML. An inverse relationship between plasma n-3 fatty acids and C-reactive protein in healthy individuals. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1154–1156. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohsawa M, Itai K, Onoda T, Tanno K, Sasaki S, et al. Dietary intake of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is inversely associated with CRP levels, especially among male smokers. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris WS, Von Schacky C. The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Prev Med. 2004;39:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, de Lezenne Coulander C. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1205–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505093121901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daviglus ML, Stamler J, Orencia AJ, Dyer AR, Liu K, et al. Fish consumption and the 30-year risk of fatal myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1046–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2:757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marik PE, Varon J. Omega-3 dietary supplements and the risk of cardiovascular events: a systematic review. Clin Cariol. 2009;32:365–372. doi: 10.1002/clc.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris WS, Pottala JV, Sands SA, Jones PG. Comparison of the effects of fish and fish-oil capsules on the n 3 fatty acid content of blood cells and plasma phospholipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1621–1625. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed CF. Phospholipid exchange between plasma and erythrocytes in man and the dog. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:749–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI105770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Heart Association Nutrition C. Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;114:82–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ American Heart Association. Nutrition C Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aarsetoey H, Aarsetoey R, Lindner T, Staines H, Harris WS, et al. Low levels of the omega-3 index are associated with sudden cardiac arrest and remain stable in survivors in the subacute phase. Lipids. 2011;46:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3511-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]