Abstract

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a prevalent and dangerous behavior among young adults, but no treatments specific to NSSI have been developed for patients without borderline personality disorder. The purpose of this study was to develop and investigate a novel intervention for NSSI among young adults. The intervention is a 9-session behavioral treatment designed to decrease the frequency of NSSI behaviors and urges. Using an open pilot design, feasibility and acceptability were investigated in a small sample (n = 12) over a 3-month follow-up period. A preliminary investigation of change in NSSI was also conducted. Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention were supported. Medium to large effect sizes were found for decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges over the follow-up period. Results of this open pilot trial support the further evaluation of this intervention.

Keywords: nonsuicidal self-injury, treatment development, treatment outcome research

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as deliberate harm to the body without intent to die and includes acts such as cutting, burning, carving words, designs, or symbols into the skin, scratching and skin picking, and self-hitting. The behavior is especially prevalent among young adults (Rodham & Hawton, 2009). Although NSSI is well documented among clinical samples (e.g., Briere & Gil, 1998; Nijman et al., 1999; Zlotnick, Mattia, & Zimmerman, 1999), the behavior is also highly prevalent among nonclinical samples. Researchers have reported rates of NSSI ranging from 12% to as high as 38% among young adults (e. g., Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002; Muehlenkamp & Guttierez, 2004).

The prevalence of NSSI is alarming, especially when the significant consequences of the behavior are considered. By definition, NSSI results in physical injury ranging in medical severity and physical disfiguration. The behavior is frequent and repetitive (Muehlenkamp, 2005), placing the individual at continual risk of physical harm. These behaviors are likely to increase in level of risk or lethality over time, resulting in more severe injuries, attempted suicide, or even death (Briere & Gil, 1998; Stellrecht et al., 2006). In fact, research indicates that individuals who engage in NSSI may underestimate the lethality of their behaviors (Stanley, Gameroff, Michalsen, & Mann, 2001) or may habituate to the physical and emotional pain inherent in death by suicide (Van Orden, Merrill, & Joiner, 2005), increasing the possibility of suicide or unintentional death. Further, individuals are impacted by social stigma, guilt, shame, and social isolation associated with the behavior (Gratz, 2003). Though researchers and clinicians alike consider NSSI difficult to treat (e.g., Muehlenkamp, 2006; Walsh & Rosen, 1988; Zila & Kiselica, 2001), the severe nature of the behavior necessitates intervention in order to preclude further negative consequences.

Despite the importance of treating NSSI (Arensman et al., 2001), only one intervention has been developed and evaluated specifically for the behavior. Gratz and colleagues (Gratz & Gunderson, 2006; Gratz & Tull, 2011) developed an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy (ERGT) for women with borderline personality disorder (BPD) to reduce the frequency of NSSI. Compared to those receiving treatment as usual (TAU), women with BPD and subclinical BPD receiving ERGT and TAU reported greater decreases in NSSI following treatment (Gratz & Gunderson; Gratz & Tull). A relatively larger body of research exists for the treatment of deliberate self-harm (DSH), which, unlike NSSI, includes behaviors performed both with and without suicidal intent. Although NSSI and DSH both involve deliberate injury to the body, research on the treatment of DSH may not generalize to the treatment of NSSI because of the inclusion of suicide attempts, a distinct category of self-injury (Muehlenkamp, 2005, 2006). Some DSH treatment studies, however, have specifically reported NSSI as an outcome variable. One study specifically investigated manual assisted cognitive therapy (MACT), a cognitive-behavioral intervention with a focus on problem solving developed to treat DSH (Evans et al., 1999; Salkovskis, Atha, & Storer, 1990; Tyrer et al., 2003), for the treatment of NSSI among women with BPD. The authors found that MACT in addition to TAU was more effective than TAU alone at decreasing NSSI (Weinberg, Gunderson, Hennen, & Cutter, 2006). Although additional research is necessary, problem-solving therapy may be a promising intervention for reducing NSSI, especially when combined with other cognitive behavioral techniques (Evans, 2000; Hawton et al., 1998; Muehlenkamp, 2006).

An explicit target of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), an empirically supported treatment (EST; Chambless & Hollon, 1998) for BPD, is the reduction of DSH. DBT incorporates cognitive behavioral techniques and acceptance strategies with a focus on improving emotion regulation and generally lasts for a minimum of 1 year (Linehan, 1993), although shorter lengths of treatment have been used successfully (e.g., Bohus et al., 2004; Stanley, Brodsky, Nelson, & Dulit, 2007). Several studies have reported the efficacy of DBT on reducing NSSI specifically. Among women with BPD, a 12-month course of DBT was found to be superior to TAU in decreasing NSSI (Verheul et al., 2003), with results maintained at 6-month follow-up (van den Bosch, Koeter, Stijnen, Verheul, & van den Brink, 2005). Another study comparing a 3-month inpatient DBT program to a waitlist group reported a significant reduction in NSSI at 1-month follow-up among women with BPD (Bohus et al.). An investigation of a 6-month DBT intervention, Brief DBT (DBT-B), yielded significant decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges (Stanley et al., 2007). Among college students reporting current suicidal ideation, at least three BPD symptoms, and a history of NSSI or attempted suicide, patients who received DBT reported greater decreases in NSSI than those who received TAU (Pistorello, Fruzzetti, MacLane, Gallop, & Iverson, 2012). DBT has been modified for adolescents (Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2007), but its effect on NSSI specifically has not yet been investigated in adolescent samples (Brausch & Girresch, 2012).

Despite the evidence in support of the aforementioned interventions for NSSI, there are several reasons to develop a new treatment. First, although ERGT, MACT, and DBT have demonstrated decreases in NSSI, these interventions were developed to treat NSSI or DSH among individuals with BPD, and studies have only included participants with BPD diagnoses or predominant BPD symptoms. NSSI, however, occurs across psychiatric disorders (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006) and often occurs outside a BPD diagnosis (Andover, Pepper, Ryabchenko, Orrico, & Gibb, 2005). Additional research is necessary to investigate the efficacy of these interventions in treating NSSI in non-BPD samples. Further, individuals without BPD may benefit from an intervention designed to specifically target NSSI that can either be used alone when appropriate or integrated into treatments for co-occurring disorders. Second, DBT, the intervention with the most empirical support in the reduction of NSSI, ranges from 3 months to 1 year of intensive—sometimes inpatient—treatment (e.g., Bohus et al., 2004; Verheul et al., 2003) that includes individual therapy, group therapy, telephone consultation for patients, and case consultation for therapists. Given the prevalence of the behavior, treating NSSI with DBT may not be practical from the perspectives of both cost and available resources (e.g., Pasieczny & Connor, 2011), and DBT may be more intensive than necessary for reducing NSSI in non-BPD samples (Comtois, 2002; Comtois & Linehan, 2006). The need for a brief, feasible intervention for NSSI that could be integrated into treatments for co-occurring disorders when appropriate is evident given the lack of ESTs for NSSI in non-BPD samples and the dangerous nature of this highly prevalent behavior.

Therefore, we developed a brief intervention specifically for NSSI in young adults, the Treatment for Self-Injurious Behaviors (T-SIB). This novel intervention integrates theoretically appropriate and empirically supported strategies (e.g., Muehlenkamp, 2006; Nock, Teper, & Hollander, 2007) to reduce NSSI behaviors and urges through functional assessment, which allows for the identification of the functions and reinforcers of an individual’s NSSI, and the differential reinforcement of more adaptive coping strategies. Following recommendations for pilot studies in clinical research (Leon, Davis, & Kraemer, 2011; Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001), we conducted an open pilot trial to evaluate treatment feasibility and acceptability and conducted a preliminary investigation of change in NSSI postintervention and at 3-month follow up. The aims of the study were three-fold: to examine treatment feasibility, to examine treatment acceptability, and to examine change in NSSI behaviors and urges to engage in NSSI using an intent-to-treat approach.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 12 treatment-seeking participants recruited through flyers and online advertisements posted on college campuses and community websites. Inclusion criteria were broad to maximize generalizability of study findings and consisted of (a) 18 to 29 years of age; and (b) engaged in NSSI involving direct tissue damage within the past month, or history of NSSI and urges to engage in NSSI within the past month. The addition of urges to engage in NSSI to the second inclusion criterion was added shortly after the study began to address the ethical concern that individuals with strong urges to self-injure would be excluded from treatment. Exclusion criteria were (a) active severe suicidal ideation as indicated by a score of 21 or greater on the Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI; Miller, Norman, Bishop, & Dow, 1986); and (b) current psychotic symptoms as indicated on the psychosis module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbons, 1995). Individuals who did not meet inclusion criteria for the current study received referrals to appropriate community resources.

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Mean age of the sample was 22.08 years (SD = 3.18). The majority of the sample was female (83.3%; n = 10). Two-thirds of the sample was Caucasian (66.6%; n = 8), 16.6% were biracial (n = 2), 8.3% were African American (n = 1), and 8.3% reported “other” race (n = 1). A quarter of the sample was Latino (n = 3), and 25% reported a previous hospitalization for a mental health reason (n = 3). Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the SCID-I and the borderline personality disorders (BPD) module of the SCID-II (First, Gibbons, Spitzer, & Williams, 1997). The majority of the sample (83.3%, n = 10) met criteria for an Axis I disorder; 58.3% (n = 7) met criteria for more than one Axis I disorder. Half the sample met criteria for major depressive disorder (50.0%, n = 6). In addition, participants met criteria for specific phobia (25%, n = 3), social anxiety disorder (25%, n = 3), generalized anxiety disorder (16.7%, n = 2), dysthymia (16.7%, n = 2), substance abuse (16.7%, n = 2), substance dependence (16.7%, n = 2), obsessive-compulsive disorder (8.3%, n = 1), panic disorder without agoraphobia (8.3%, n = 1), panic disorder with agoraphobia (8.3%, n = 1), bipolar II disorder (8.3%, n = 1), and anxiety disorder NOS (8.3%, n = 1). A third of the sample (33.3%, n = 4) met criteria for BPD.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Mean (SD)/% (n) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| % Female | 83.3% (10) |

| Age | 22.08 (3.18) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 66.6% (8) |

| African American | 8.3% (1) |

| Biracial | 16.6% (2) |

| Other | 8.3% (1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| % Latino | 25.0% (3) |

| Axis I Disorders | |

| Mood Disorders | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 50.0% (6) |

| Dysthymia | 16.7% (2) |

| Bipolar II Disorder | 8.3% (1) |

| Anxiety Disorders | |

| Specific Phobia | 25.0% (3) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 25.0% (3) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 16.7% (2) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 8.3% (1) |

| Panic Disorder with or without Agoraphobia | 16.7% (2) |

| Anxiety Disorder NOS | 8.3% (1) |

| Substance-Related Disorders | |

| Substance Abuse | 16.7% (2) |

| Substance Dependence | 16.7% (2) |

| Axis II Disorders | |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 33.3% (4) |

| NSSI within Past Month | |

| NSSI Behaviors | 75.0% (9) |

| NSSI Urges Only | 25.0% (3) |

Note. NSSI = Nonsuicidal self-injury

All participants reported a history of NSSI. The majority of the sample (75.0%, n = 9) reported at least one episode of NSSI within the past month, and 25.0% (n = 3) reported no NSSI behaviors within the past month, but urges to self-injure. Of those who engaged in NSSI within the past month, methods reported included cutting (50.0%, n = 4), skin picking (50.0%, n = 4), hitting (37.5%, n = 3), scratching (25.0%, n = 2), and other method (12.5%, n = 1). Seventy-five percent (n = 6) reported engaging in multiple methods of NSSI in the past month. For the 4 weeks prior to the baseline assessment, participants reported a mean of 12.25 (SD = 19.58) NSSI episodes, and they reported engaging in NSSI on a mean of 9.33 days (SD = 12.92). NSSI urges were assessed in 6 of the 12 participants, with a mean of 18.67 urges (SD = 19.99) on a mean of 11.33 days (SD = 10.48) in the previous 4 weeks.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements. Individuals calling in response to an advertisement were given additional information about the study. If interested, callers were screened to determine whether inclusion criteria for age and NSSI behaviors or urges within the past month were met. Those meeting inclusion criteria were invited to complete a baseline assessment. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant at the beginning of the baseline assessment. The SCID-I, SCID-II, MSSI, Timeline Follow Back interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988; Beck & Steer, 1991), and the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorders (MSI-BPD; Zanarini et al., 2003) were administered at baseline. Study treatment was provided by the first author for nine sessions, usually held weekly, at a treatment space within the university. The MSSI, TLFB, BDI-II, BAI, MSI-BPD, and Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Attkisson & Zwick, 1982) were administered within 1 week posttreatment. These measures, excluding the CSQ-8, were re-administered at 3-month follow up. Posttreatment and follow-up assessments were conducted by trained assessors blind to the participant’s baseline assessment and progress in therapy. The study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were provided remuneration for assessments, and the intervention was provided free of charge.

Treatment

The intervention consists of nine weekly individual sessions lasting 1 hour each. The first session consists of psychoeducation on NSSI and exercises to address ambivalence towards behavior change. The next five sessions focus on identifying antecedents and consequences of NSSI behaviors and urges using functional assessment, the identification of alternative behaviors to be differentially reinforced, behavior change through the differential reinforcement of alternative behaviors (DRA), and ongoing assessment. Functional assessment and behavior modification continue for the next two sessions, which also focus on strengthening skills deficits hypothesized to contribute to NSSI. Skills deficits are identified through functional assessment by the therapist and patient, and sessions are selected from a choice of three modules that address different skills. The final session is focused on reviewing participant gains and relapse prevention. Sessions are discussed in detail below, and the intervention manual is available by request from the first author.

Session 1: Psychoeducation and Addressing Ambivalence

The goal of Session 1 is to provide psychoeducation regarding NSSI and to orient the patient to the intervention, which largely conceptualizes NSSI as a coping strategy. In addition, motivational enhancement techniques are utilized to address potential ambivalence and resistance towards change and to begin building motivation for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Sessions 2–6: Functional Assessment and Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behaviors

The goals of Sessions 2 to 6 are to use functional assessment to identify the triggers and reinforcers for NSSI, to identify alternative behaviors to NSSI, and to use differential reinforcement procedures to decrease engagement in NSSI and increase the use of alternative behaviors. Functional assessment provides an ongoing evaluation of the intervention.

Informant-based antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) charts are the primary method of functional assessment used in this intervention. A specific NSSI episode is entered as the behavior, and the patient and therapist work together to identify the environmental, emotional, cognitive, and social antecedents to and consequences of the behavior. If the patient is not experiencing NSSI behaviors, urges to engage in NSSI are the focus of the functional assessment, and antecedents to and consequences of the urges are examined. Functional assessments are conducted for each method of NSSI used, as methods may differ in function, and across as many situations as possible.

During Session 2, the technique is introduced and functional assessments of recent NSSI episodes are conducted. Results of the initial functional assessment conducted in Session 2 may suggest environmental strategies that can be immediately implemented to potentially decrease NSSI behaviors. For example, a patient who self-injures in a particular setting, such as in the bathroom, may be encouraged to limit time in that setting. Similarly, a patient may be encouraged to put tape around a sharp implement to make access to the tool more difficult, thereby giving the patient more opportunity to use an adaptive strategy. These manipulations are then assessed in future functional assessments. Homework is introduced in Session 2 and is an important component of the intervention; the patient is instructed to complete a functional assessment for each episode of NSSI or NSSI urge during the week, which is then reviewed at the beginning of each session.

Because the majority of patients endorse automatic negative reinforcement as a primary function of NSSI (Nock & Prinstein, 2004), Sessions 3 and 4 focus on identifying adaptive ways to decrease negative affect so that the individual can use other coping skills in their repertoire to address an antecedent to NSSI behaviors and urges. During Session 3, the functional assessment is continued and expanded to include an occasion where the patient experienced an antecedent that often leads to NSSI, but he or she did not self-injure. With significant collaboration between the patient and therapist, the focus of Session 4 is to identify alternative behaviors that serve a similar function for the patient’s NSSI. Techniques that the patient has used in the past to successfully cope with NSSI urges, along with patient preferences for distraction techniques, are focused upon. The therapist collaborates with the patient to develop a list of possible alternative behaviors that are simple and easily accessible (i.e., not overly complicated or relying on equipment to which the patient may not have access). For homework, the patient is asked to practice these techniques in response to mild negative affect and to perform a functional assessment on each occurrence. The patient is not asked to use alternative behaviors as a substitution for NSSI in Session 4. In Session 5, the patient’s experiences in performing the homework assignment are incorporated, and the list of alternative behaviors is revised. The patient is asked for homework to test these behaviors in lieu of NSSI, again performing a functional assessment on each instance. During Session 6, the list of alternative behaviors is again revised based on patient experiences. Alternative behaviors are reinforced by the desired consequences—for example, reducing negative affect—thus increasing the likelihood that the alternative behavior will be repeated and decreasing the likelihood of NSSI through DRA.

Sessions 7 and 8: Individualized Modules

For the remainder of the intervention, the patient continues to practice utilizing alternative behaviors in lieu of NSSI. Functional assessments assigned for homework throughout the week are reviewed at the beginning of each session, and the list of alternative behaviors is revised as necessary to ensure that the alternative behaviors are reinforced, thus contributing to behavior change through DRA. The content of Sessions 7 and 8 consists of one of three individualized modules: Interpersonal Communication, Cognitive Distortions, and Distress Tolerance. Based on the common antecedents identified in the functional assessments and patient feedback, the therapist and patient hypothesize deficits in coping that may be contributing to NSSI and select the module most related to these deficits. For example, patients whose NSSI has a communication function or appears to be related to deficits in interpersonal communication may receive the Interpersonal Communication module; those whose NSSI is related to cognitive distortions or core beliefs, such as worthlessness or a need to be punished, may receive the Cognitive Distortions module; and those who engage in NSSI for automatic negative reinforcement without a relevant interpersonal or cognitive trigger may receive the Distress Tolerance module. Module selection is flexible, and modules are chosen to best address the skills deficits most related to current NSSI episodes. The goals of the Interpersonal Communication module are to increase the patient’s assertiveness skills, particularly in situations that may trigger NSSI, and to practice these skills using role-play. The goals of the Cognitive Distortions module, based on principles and techniques of cognitive therapy, are to introduce the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, to identify cognitive distortions that may contribute to NSSI, and to begin to evaluate negative automatic thoughts and generate more realistic thoughts. Similar to the Distress Tolerance module of DBT, the goals of T-SIB’s Distress Tolerance module are to discuss the concept of accepting and tolerating distressing situations and feelings, and to discuss ways of tolerating distress. Unlike DBT, however, distress tolerance skills are only a focus of the two sessions of this specific module and are not incorporated throughout the treatment. Although two sessions are not sufficient to thoroughly address deficits in any of these areas, the goal of the individualized modules is to give the patient basic skills to begin to address some of the underlying skills deficits that may be associated with their NSSI. Patients are encouraged to seek additional treatment to continue the work begun in the intervention.

Session 9: Termination

Session 9 focuses on treatment termination and relapse prevention. As such, this session has two main goals: (1) to review gains made during the treatment, and (2) to address obstacles to maintaining gains in the future. In order to review gains made in treatment, the therapist presents a line graph of NSSI behaviors and urges since the initial assessment. Decreases— and increases—in behavior are discussed with the patient using a functional assessment framework. The patient and therapist then review the skills that the patient found most helpful in reducing NSSI, including functional assessment and alternative behaviors. As part of relapse prevention, the patient and therapist discuss obstacles to maintaining gains following treatment and how they may be minimized or avoided. In addition, the potential for relapse is discussed. It is emphasized to the patient that relapse should not be considered failure, but instead an opportunity to collect new data. Recurrences of NSSI may suggest that there is another trigger or function of NSSI, which the patient should investigate with functional assessment, or that the patient’s strategies for addressing the behaviors, urges, or antecedents should be reassessed or potentially modified.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, Axis I, Non-Patient Version (SCID-I; First et al., 1995)

The SCID-I was used to assess DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses at baseline. Interrater reliability with trained interviewers for the SCID-I is high (.70 to 1.00; First et al., 1995). Validity against clinical interviews is good to superior (First et al.). To reduce participant burden, only the mood episodes, psychotic symptoms, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders modules were administered. Interrater reliability was calculated on 75% of interviews conducted; interrater reliability was high, with 95.36% concordance.

Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, Axis II Disorders (SCID-II; First et al., 1997)

The SCID-II was used to assess the presence of BPD in the sample at baseline. Previous studies have supported the interrater reliability and internal consistency of the SCID-II modules (e.g., Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991; Maffei et al., 1997). Interviewer concordance was calculated for nearly 60% of interviews (58.33%); interviewers were 91.47% reliable on the SCID-II.

Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI; Miller et al., 1986)

The MSSI, an 18-item interview modified from the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979), was used to assess patients’ levels of suicidal ideation at baseline. Excellent internal consistency and concurrent validity have been reported in clinical samples (Rudd & Rajab, 1995), and the scale has been used in a number of research studies. A score of 21 on the MSSI reflects severe levels of suicidal ideation (Miller et al., 1986). For the current study, participants receiving a score of 21 or above were excluded from participation. Interrater reliability was calculated for half of the interviews conducted; interviewers were 98.0% reliable.

Time Line Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992)

The TLFB is a retrospective, calendar-prompted interview that was used to assess NSSI behaviors and urges over a specific time period. NSSI was defined as deliberate injury to the body involving tissue damage that was performed in the absence of suicidal intent as reported by the participant. For the purposes of the current study, the number of days during which an NSSI thought or behavior occurred, the number of episodes, or sessions, of NSSI thoughts and behaviors, and the total number of NSSI thoughts and behaviors were assessed. The TLFB has been used extensively in alcohol research with excellent reliability and validity (Sobell & Sobell, 1992), and has been successfully used to assess NSSI (Glenn & Klonsky, 2011). The TLFB was administered at baseline (following back 4 weeks), posttreatment (following back 4 weeks), and 3-month follow-up (following forward 12 weeks from the posttreatment assessment).

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996)

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II has demonstrated good internal consistency and retest reliability (Beck et al., 1996; Steer & Clark, 1997). The BDI-II also has good convergent validity (Beck et al.). The BDI-II was administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up. Cronbach’s alphas for the BDI-II at each administration were .91, .87, and .96, respectively.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988; Beck & Steer, 1991)

The BAI consists of 21 items measuring neurophysiological, autonomic, subjective, and panic symptoms of anxiety (Beck & Steer, 1991). The reliability and validity of the BAI have been supported in numerous studies (Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Osman, & Wade, 1997). The BAI was administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up. Cronbach’s alphas for the BAI at each administration were .93, .87, and .88, respectively.

McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD; Zanarini et al., 2003)

The MSI-BPD, a 10-item self-report questionnaire, reflects the criteria of BPD in the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. It was administered at baseline, postintervention, and 3-month follow-up to assess BPD characteristics. The MSI-BPD has shown good sensitivity and specificity when compared to the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini et al., 2003). Cronbach’s alphas for the MSI-BPD at each administration were .56, .59, and .83, respectively.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Attkisson & Zwick, 1982)

The CSQ-8 was administered posttreatment to assess patient satisfaction with treatment. The CSQ-8 demonstrates high validity and reliability (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982). Cronbach’s alpha for the CSQ-8 in the present study was .78.

Results

Of the 12 participants, 9 completed the intervention. Two participants withdrew from the study after two sessions, and 1 participant could not be contacted after seven sessions. These participants could not be reached to conduct postintervention or follow-up assessments. Of the 9 treatment completers, 8 completed all nine 1-hour sessions 1 one completed the intervention after seven 1-hour sessions. (This participant was beginning cognitive therapy with an outside therapist; together with the patient and therapist, we decided to omit the individualized module to allow for earlier termination.) Mean number of sessions attended for all participants was 7.50 (SD = 2.68). Half of participants completed the Cognitive Distortions individualized module (n = 4), 3 completed Interpersonal Communication, and 1 completed Distress Tolerance. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.

Feasibility and Acceptability

In order to evaluate treatment feasibility, we first examined recruitment. Twenty-seven individuals responded to advertisements to learn more about the research study, 25 of whom completed a telephone screen. Twenty-two individuals were eligible to complete the baseline assessment per telephone screen. Nearly all (n = 21) scheduled a baseline assessment, but only 13 attended the baseline assessment. Of the individuals who attended the baseline assessment, 12 were eligible to participate, and all 12 enrolled in the research study.

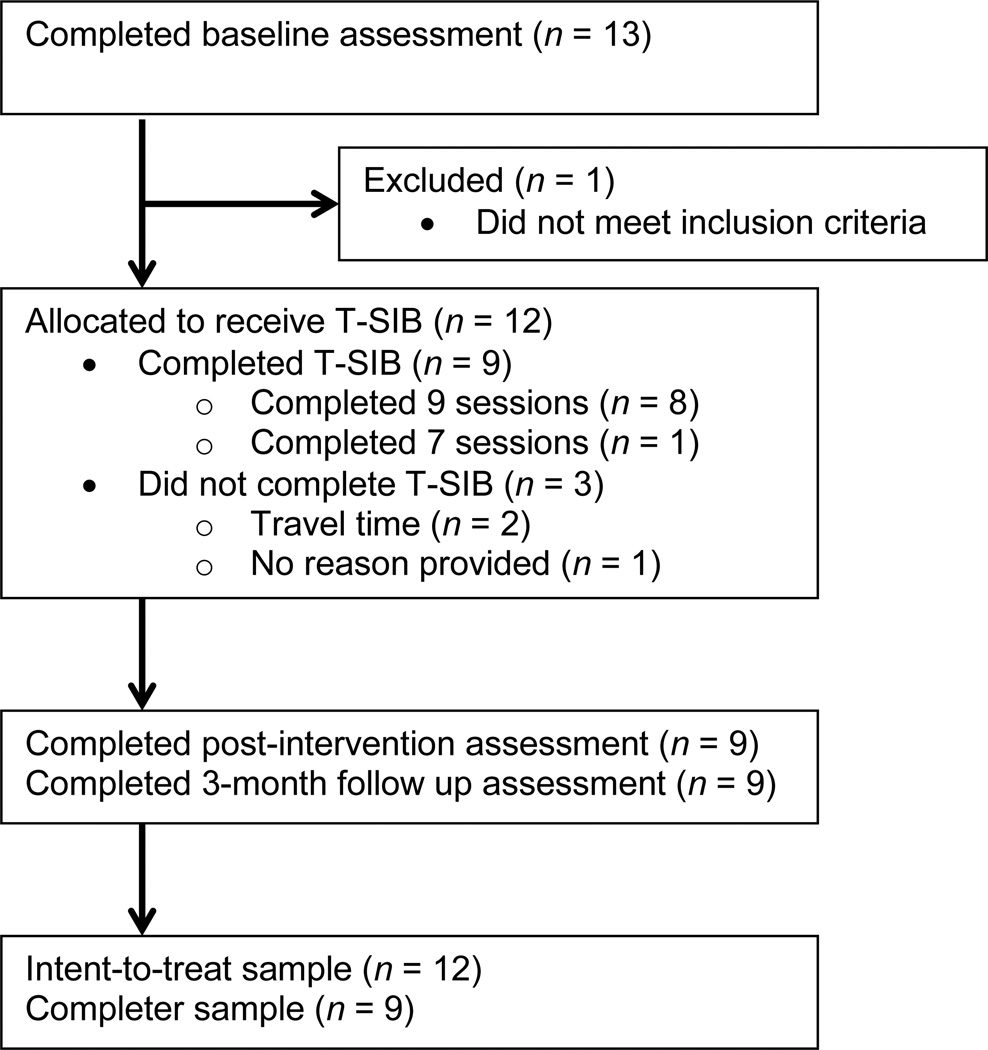

We next examined retention of participants in the study. As seen in Figure 1, of the 12 patients enrolled in the study, 9 completed the intervention. Three patients withdrew from treatment; 2 patients withdrew because of difficulty traveling to and from the treatment site, and 1 could not be reached to provide a reason. These patients could not be reached to complete postintervention or follow-up assessments.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of patient enrollment and disposition.

Overall, patients reported high satisfaction with the intervention on the CSQ8 (M = 29.29, SD = 2.85; CSQ8 Range = 8–32). When asked to report specific aspects of the treatment that were especially helpful on the CSQ8, one patient stated, “The most helpful part was the fact that there was someone to report to, to whom I was accountable.” Another patient wrote, “The most helpful aspect was the tools/techniques I was given to stop picking as much. I don’t think there was anything that wasn’t helpful to me or that wouldn’t be helpful for anyone else.” Two patients noted the functional assessments as being helpful, one noted alternative behaviors, and one noted treatment alliance. The only negative feedback received was length of assessments.

Change in NSSI Behaviors and Urges

Although the sample size in this open pilot was not large enough to obtain adequate power to investigate statistical significance, we conducted analyses to provide an initial investigation of statistically significant change, clinically significant change, and patterns of change in NSSI behaviors and urges from pretreatment to posttreatment and from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up. Specifically, we investigated (a) the number of NSSI episodes or NSSI urges in a 1-month period, and (b) the number of days during which the patient engaged in NSSI or experienced NSSI urges (consistent with the proposed NSSI diagnosis in DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2012). Behaviors were assessed for the 4 weeks prior to the pretreatment assessment and the posttreatment assessment, and for the 12 weeks after the posttreatment assessment at the 3-month follow up. Consistent with an intention-to-treat approach, analyses included the 12 participants who enrolled in the study.

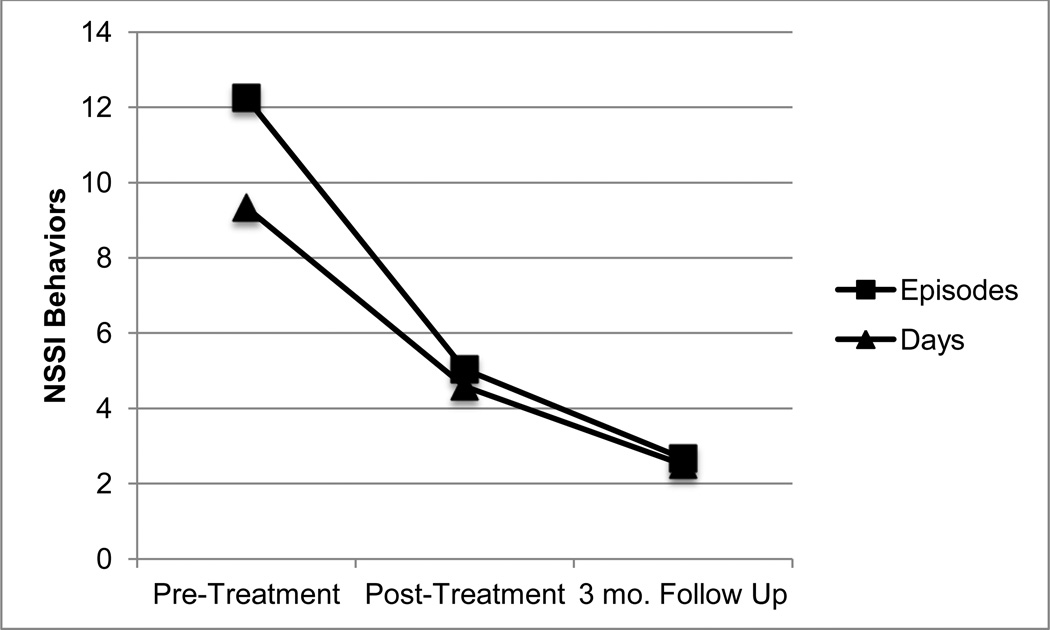

Statistically Significant Change

Two-tailed paired samples t-tests were first conducted on all study outcome variables from pretreatment to posttreatment (see Table 2). Results indicated nonsignificant differences from pretreatment to posttreatment on the number of NSSI episodes, t(11) = 1.52, p = .16, d = .48, and the number of days engaged in NSSI, t(11) = 1.85, p = .09, d = .43. Similarly, the pretreatment to posttreatment differences between number of NSSI urges, t(5) = 1.82, p = .13, d = 1.13, and number of days of NSSI urges, t(5) = 1.82, p = .13, d = 1.17, were nonsignificant. There were no significant differences on clinical variables, although a nonsignificant trend was noted for pretreatment to posttreatment depression severity, t(10) = 2.12, p = .06, d = .59. Change in outcome variables was then investigated between pretreatment and 3-month follow-up (see Table 3). For NSSI variables, two scores were calculated: the mean of the variable over the 3-month follow-up period, and the number of occurrences over the last 4 weeks in the assessment period. Although there were no significant differences between pretreatment and 3-month follow-up, a trend towards significance was noted for the number of days engaged in NSSI in the 4 weeks prior to the assessment, t(11) = 1.99, p = .07, d = .68, and the mean follow-up period, t(11) = 1.96, p = .08, d = .71. Decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges were maintained between posttreatment and 3-month follow up assessments (see Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences for Study Outcomes from Pre- to Posttreatment

| Pre-Treatment |

Post-Treatment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | d | RCI | |

| Behaviors | |||||||||

| Episodes | 12.25 | 19.58 | 5.04 | 8.57 | 1.52 | 11 | .16 | 0.48 | 1.52 |

| Days | 9.33 | 12.98 | 4.58 | 8.45 | 1.85 | 11 | .09 | 0.43 | 1.85 |

| Urges | |||||||||

| Episodes | 18.67 | 19.99 | 2.50 | 2.88 | 1.82 | 5 | .13 | 1.13 | 1.82 |

| Days | 11.33 | 10.48 | 2.33 | 2.94 | 1.82 | 5 | .13 | 1.17 | 1.82 |

| MSI-BPD | 5.42 | 2.11 | 5.25 | 2.22 | 0.46 | 11 | .66 | 0.08 | 0.46 |

| BAI | 19.28 | 12.90 | 13.58 | 8.82 | 1.86 | 11 | .09 | 0.52 | 1.86 |

| BDI-II | 20.60 | 11.93 | 14.27 | 9.54 | 2.12 | 10 | .06 | 0.59 | 2.12 |

| MSSI | 1.50 | 3.06 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 1.31 | 11 | .38 | 0.43 | 1.31 |

| CSQ | 29.29 | 2.85 | |||||||

Note. RCI = Reliable Change Index. MSI-BPD = McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II. MSSI = Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation. CSQ = Client Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences From Pretreatment to 3-Month Follow-up for Study Outcomes

| Pre-Treatment |

3 Month Follow Up |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | d | RCI | |

| Behaviors | |||||||||

| Episodes (Monthly Average) | 12.25 | 19.58 | 2.33 | 5.36 | 1.77 | 11 | .11 | 0.69 | 1.77 |

| Episodes (Last Month) | 12.25 | 19.58 | 2.67 | 5.87 | 1.73 | 11 | .11 | 0.66 | 1.73 |

| Days (average Per month) | 9.33 | 12.98 | 2.28 | 5.35 | 1.96 | 11 | .08 | 0.71 | 1.95 |

| Days (Last Month) | 9.33 | 12.98 | 2.50 | 5.66 | 1.99 | 11 | .07 | 0.68 | 1.99 |

| Urges | |||||||||

| Episodes (Average Per Month) | 18.67 | 19.99 | 2.22 | 2.52 | 1.93 | 5 | .11 | 1.15 | 1.93 |

| Episodes (Last Month) | 18.67 | 19.99 | 2.83 | 2.40 | 1.84 | 5 | .13 | 1.11 | 1.84 |

| Days (Average Per Month) | 1.33 | 10.48 | 2.22 | 2.52 | 2.08 | 5 | .09 | 1.19 | 2.08 |

| Days (Last Month) | 11.33 | 10.48 | 2.83 | 2.40 | 1.87 | 5 | .12 | 1.12 | 1.87 |

| MSI-BPD | 5.42 | 2.11 | 5.17 | 2.86 | 0.38 | 11 | .71 | 0.10 | 0.38 |

| BAI | 19.28 | 12.90 | 14.50 | 8.73 | 1.46 | 11 | .17 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

| BDI | 20.60 | 11.93 | 18.45 | 14.69 | 0.71 | 10 | .50 | 0.16 | 0.71 |

| MSSI | 1.50 | 3.06 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 11 | .38 | 0.37 | 0.91 |

Note. RCI = Reliable Change Index. MSI-BPD = McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II. MSSI = Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Figure 2.

Change in NSSI behaviors over the assessment period. NSSI = Nonsuicidal self-injury.

Figure 3.

Change in NSSI urges over the assessment period. NSSI = Nonsuicidal self-injury.

Clinically Significant Change

In addition to examining statistical significance, we investigated the clinical relevance of the results; specifically, clinical significance and treatment response. First, we computed reliable change indices for each of the study outcome variables (see Tables 2 and 3). A reliable change index (RCI) of 1.96 or above is considered to be clinically significant change (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Clinically significant change from pretreatment to posttreatment was found for depression severity (RCI = 2.12), and change approaching clinical significance was found for the number of days during which an individual engaged in NSSI (RCI = 1.85), the number of NSSI urges (RCI = 1.82), and the number of days on which an individual experienced the urge to self-injure (RCI = 1.82). From pretreatment to 3-month follow-up, clinically significant change was found for the number of days in the past month the individual engaged in NSSI (RCI = 1.99), and a trend towards clinically significant change was found for the average number of days during which the participant engaged in NSSI (RCI = 1.95). A clinically significant change was found for the average number of days per month the individual experienced urges to engage in NSSI (RCI = 2.08), and a trend towards clinical significance was noted for the average number of NSSI urges experienced per month (RCI = 1.93) and during the last month (RCI = 1.84).

We then investigated treatment response, defined for this study as at least a 50% reduction in NSSI behaviors from pretreatment, among individuals who completed the treatment. At the posttreatment assessment, five of the nine patients (55.6%) reported over a 50% reduction in NSSI episodes and number of days engaged in NSSI. At 3-month follow-up, seven of the nine participants (77.8%) reported over a 50% reduction in the number of days engaged in NSSI in the past 4 weeks, and six of the nine (66.7%) reported over a 50% reduction in NSSI episodes in the last 4 weeks of the assessment period.

Discussion

The purpose of this open pilot trial was to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of a novel intervention to reduce NSSI in young adults and to provide a preliminary examination of change in NSSI behaviors and urges over a 3-month follow-up period. Data from the open pilot trial supports each of these aims, suggesting that further research on the Treatment for Self-Injurious Behaviors (T-SIB) as a treatment for NSSI in young adults is warranted.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Overall, the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention were supported. Three quarters of those who completed an initial assessment completed the intervention, and attrition rates were consistent with other studies of NSSI interventions (i.e., Bohus et al., 2004). Those who withdrew from the intervention cited reasons such as travel time to and from the treatment site; for both participants citing travel time as a reason for withdrawal, travel time was over 2 hours one way. The majority of patients completed all nine sessions of the intervention, and patients reported high satisfaction with the intervention per self-report assessment. When asked to identify the components of treatment that were most helpful, participants either cited specific skills taught in the intervention or the relationship with the therapist, which is considered to be an important aspect of NSSI treatment (Muehlenkamp, 2006; Nafisi & Stanley, 2007). Although the study was not designed to investigate mechanisms of change, it is encouraging that patients identified specific components of the treatment as being most helpful.

Change in NSSI Behaviors and Urges

Given the small sample size of this open pilot, we did not anticipate obtaining adequate power to detect statistical differences in NSSI behaviors and urges. However, a preliminary investigation of change in NSSI over a 3-month follow-up period was conducted. There were no statistically significant differences in NSSI behaviors or urges between pretreatment and posttreatment assessments, or between pretreatment assessment and 3-month follow-up. However, effect sizes for decrease in NSSI behaviors were medium at posttreatment and medium to large at 3-month follow-up, and effect sizes for decrease in NSSI urges were “much larger than typical” at posttreatment and 3-month follow-up (Kraemer et al., 2003; p. 1525). Effect sizes alone should not dictate success in an open pilot trial, as they are unstable in small samples. As a measure of clinical significance, however, the effect sizes found for decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges in the current study were promising (Kraemer et al.).

Clinically significant change was also investigated using a reliable change index. We found a clinically significant difference in the number of days the individual engaged in NSSI from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up. Clinically significant change in the number of days an individual experienced an urge to engage in NSSI from pretreatment to 3-month follow-up was also detected. Further, over half of participants who completed the intervention reported greater than a 50% decrease in NSSI behaviors and number of days engaged in NSSI at posttreatment. At 3-month follow-up, nearly 80% reported greater than a 50% reduction in the number of days engaged in NSSI, and two-thirds reported greater than a 50% reduction in NSSI behaviors. Importantly, treatment gains reported at posttreatment assessment were either maintained or improved upon over the 3-month follow-up period. Although NSSI is difficult to treat, the results of this open pilot are consistent with research suggesting that the behavior can be effectively treated (Nock et al., 2007).

Limitations

Several limitations must be noted for the study, several of which are inherent in the open pilot design. First, all participants received the intervention, and there was no control group. Although this is appropriate for an open pilot trial (Leon et al., 2011; Rounsaville et al., 2001), it limits the conclusions that can be drawn without a no-treatment comparison group. Second, the sample size was too small to obtain adequate power to detect statistically significant differences. Although effect sizes ranging from medium to large were promising, they must be viewed together with feasibility and acceptability data for the study, and results of the study must be replicated with a larger sample. Finally, there was only one therapist for the study. Future research should be conducted with more than one therapist to rule out therapist effects. Although these are important limitations to consider, they are integral to the design of open pilot trials, which are an essential step in the development and evaluation of a novel treatment (Leon et al.; Rounsaville et al.).

Conclusion and Future Directions

This open pilot trial provides initial support for the feasibility and acceptability of the Treatment for Self-Injurious Behaviors. Although effect sizes alone should not be used to determine the potential of a treatment (Kraemer, Mintz, Nota, Tinklenberg, & Yesavage, 2006), together with data on feasibility and acceptability, effect sizes provide initial data about the potential strength of a novel intervention. The data on treatment feasibility, acceptability of the intervention to patients, medium to large effect sizes, and clinically significant change for decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges supports the further evaluation of this intervention in a randomized clinical trial, which would allow for the direct evaluation of the intervention against a treatment as usual or waitlist comparison. In addition, future research with a larger sample size should investigate severity of NSSI as a possible moderating variable, as T-SIB may be more beneficial for individuals with a particular level of severity.

Although not specifically investigated, therapist experience and patient feedback suggest that the main components of intervention are functional assessment and differential reinforcement of other behaviors. Although the individualized modules are important in addressing skills deficits related to NSSI, it is unlikely that these deficits are adequately addressed in the two sessions currently allotted, and the individualized modules may be a less potent component of treatment as outlined in the current manual. Future iterations of T-SIB may choose to extend the number of sessions, particularly to extend the number of sessions allotted to the individual modules. Although its current design gives the patient an introduction to the basic skills for each module, patients may benefit from more tools and more time to practice utilizing the tools outside of sessions. Future revisions of the intervention may also include booster sessions following termination to allow for further coaching and accountability. In addition, the brief duration of treatment and specific focus on NSSI may make T-SIB suitable for integration into treatments for other psychiatric disorders experienced by patients who engage in NSSI, such as treatments for depression or anxiety disorders; its utility as an adjunctive intervention should be investigated.

Although the study was not adequately powered to detect significant differences, medium to large effect sizes and clinically significant change in NSSI behaviors and urges were found. Treatment gains were maintained over a 3-month follow-up period. In addition, less improvement was detected for symptoms not targeted in the treatment, such as suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, and BPD symptoms, suggesting that, as intended, the intervention targets NSSI behaviors and not other psychiatric symptoms. Together with data on treatment feasibility and acceptability, this study provides initial support for the Treatment of Self-Injurious Behaviors as an intervention for NSSI among a treatment-seeking sample of young adult outpatients.

Highlights.

We developed an intervention for NSSI and investigated it in an open pilot trial.

The intervention is a 9-session behavioral treatment.

Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention were supported.

Medium to large effect sizes were found for decreases in NSSI behaviors and urges.

Results of this open pilot trial support the further evaluation of the intervention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant K23MH082824.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Margaret S. Andover, Fordham University

Heather T. Schatten, Fordham University

Blair W. Morris, Fordham University

Ivan W. Miller, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

References

- American Psychiatric Association. V 01 Non-suicidal self injury. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=443.

- Andover MS, Pepper CM, Ryabchenko KA, Orrico EG, Gibb BE. Self-mutilation and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Suicide & Life-Threatening behavior. 2005;35:581–591. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arensman E, Townsend E, Hawton K, Bremner S, Feldman E, Goldney R, Träskman-Bendz L. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatment of patients following deliberate self-harm: The methodological issues involved in evaluating effectiveness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31:169–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.2.169.21516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1982;5:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Relationship between the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale with anxious outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1991;5:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Manual. Texas: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bohus M, Haaf B, Simms T, Limberger MF, Schmahl C, Unckel C, Linehan M. Effectiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: A controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:487–499. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Girresch SK. A review of empirical treatment studies for adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2012;26:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA. A review of interventions to reduce the prevalence of parasuicide. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1138–1144. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Psychosocial treatments of suicidal behaviors: A practice-friendly review. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:161–170. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Tyrer P, Catalan J, Schmidt U, Davidson K, Dent J, Thompson S. Manual-assisted cognitive-behaviour therapy (MACT): A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:19–25. doi: 10.1017/s003329179800765x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbons M, Spitzer RL, Williams J. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbons M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV--Patient version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury: A 1-year longitudinal study in young adults. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Targeting emotion dysregulation in the treatment of self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63:1091–1103. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG. Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. Extending research on the utility of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:316–326. doi: 10.1037/a0022144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–489. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Morgan GA, Leech NL, Gliner JA, Vaske JJ, Harmon RJ. Measures of clinical significance. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1524–1529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei C, Fossati A, Agostoni I, Barraco A, Bagnato M, Deborah D, Petrachi M. Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II), version 2.0. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11:279–284. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Norman WH, Bishop SB, Dow MG. The Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:724–725. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2 nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ. Self-injurious behavior as a separate clinical syndrome. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:324–333. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ. Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2006;28:166–185. [Google Scholar]

- Nafisi N, Stanley B. Developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance with self-injuring patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. 2007;63:1069–1079. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman HL, Dautzenberg M, Merckelbach HL, Jung P, Wessel I, del Campo JA. Self-mutilating behaviour of psychiatric inpatients. European Psychiatry. 1999;14:4–10. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)80709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Teper R, Hollander M. Psychological treatment of self-injury among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. 2007;63:1081–1089. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Osman JR, Wade T. The Beck Anxiety Inventory: Reexamination of factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;53:7–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199701)53:1<7::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasieczny N, Connor J. The effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy in routine public mental health settings: An Australian controlled trial. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2011;49:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistorello J, Fruzzetti AE, MacLane C, Gallop R, Iverson KM. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0029096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodham K, Hawton K. Epidemiology and phenomenology of nonsuicidal self-injury. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Rajab MH. Use of the modified scale for suicidal ideation with suicide ideators and attempters. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:632–635. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199509)51:5<632::aid-jclp2270510508>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM, Atha C, Storer D. Cognitive-behavioural problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide: A controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157:871–876. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Allen RJ, editor. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brodsky B, Nelson JD, Dulit R. Brief dialectical behavior therapy (DBT-B) for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11:337–341. doi: 10.1080/13811110701542069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Gameroff MJ, Michalsen V, Mann JJ. Are suicide attempters who self-mutilate a unique population? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:427–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Clark DA. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with college students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 1997;30:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stellrecht NE, Gordon KH, Van Orden K, Witte TK, Wingate LR, Cukrowicz KC, Joiner TE. Clinical applications of the interpersonal-psychological theory of attempted and completed suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:211–222. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P, Thompson S, Schmidt U, Jones V, Knapp M, Davidson K, Wessely S. Randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive behavior therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self-harm: The POPMACT study. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:969–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, Stijnen T, Verheul R, van den Brink W. Sustained efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1231–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Merrill KA, Joiner TE. Interpersonal-psychological precursors to suicidal behavior: A theory of attempted and completed suicide. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2005;1:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, de Ridder MAJ, Stijnen T, van den Brink W. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomized clinical trial in the Neatherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BW, Rosen PM. Self-mutilation: Theory, research, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg I, Gunderson JG, Hennen J, Cutter CJ. Manual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patients. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:482–492. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.5.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;17:568–573. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zila LM, Kiselica MS. Understanding and counseling self-mutilation in female adolescents and young adults. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2001;79:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Mattia JI, Zimmerman M. Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in a sample of general psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:296–301. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]