Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to determine whether visual and automated REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) methods could accurately diagnose idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (iRBD) patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Methods

We visually analyzed RSWA phasic burst durations; phasic, tonic and “any” muscle activity by 3-second mini-epochs; phasic activity by 30-second (AASM rules) epochs; and automated REM atonia index (RAI) analysis in iRBD patients (n=15) and matched controls (n=30) with and without OSA. Group RSWA metrics were analyzed with regression models. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to determine the best diagnostic cutoff thresholds for REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Both split-night and full-night polysomnographic studies were analyzed.

Results

All mean RSWA phasic burst durations and muscle activities were higher in iRBD patients than in controls (p<0.01). Muscle activity (phasic, “any”) cutoffs for 3-second mini-epoch scorings were: submentalis (SM) (15.8%, 19.5%), anterior tibialis (AT) (29.7%, 29.7%), and combined SM/AT (39.5%, 39.5%). Tonic muscle activity cutoff was 0.70% and RAI (SM) cutoff 0.86. Phasic muscle burst duration cutoffs were SM (0.66) and AT (0.71) seconds. Combining phasic burst durations with RSWA muscle activity improved sensitivity and specificity of iRBD diagnosis.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence for quantitative RSWA diagnostic thresholds applicable in iRBD patients with OSA. Our findings in this study were quite similar to those seen in Parkinson's disease-REM sleep behavior disorder (PD-RBD) patients, consistent with a common mechanism and presumed underlying etiology of synucleinopathy in both groups.

Keywords: REM sleep without atonia, REM sleep behavior disorder, obstructive sleep apnea, quantitative analysis, phasic muscle burst activity and duration, tonic muscle activity, diagnosis, threshold cutoffs, AASM, idiopathic

Introduction

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a potentially injurious parasomnia that is strongly linked to synucleinopathy neurodegeneration, often presenting several years prior to development of clinical symptoms of parkinsonism or cognitive decline.[1-5] Therefore accurate diagnostic methods to distinguish at-risk individuals are needed for prognostic counseling and eventual application of neuroprotective therapies to prevent other neurodegenerative consequences of synucleinopathy. The presence of elevated REM sleep muscle tone on polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for a diagnosis of RBD, since RBD can be difficult to distinguish from non-REM parasomnias or disorders of arousal based on clinical history alone.[3] Several methods for quantifying REM sleep muscle atonia loss have been developed.[6-18] Three terms for muscle activity have been defined during REM sleep: phasic (aka transient), comprised of short muscle bursts with amplitude four times greater than the background electromyogram (EMG); tonic, comprised of long-duration muscle activity greater than half of an epoch (or at least 15 seconds in duration), and having an amplitude of two times greater than the background EMG, and, “any” which combines phasic, tonic, and muscle activity not meeting either of the other definitions.[11-13, 15] The majority of previous quantitative RSWA studies have been performed by visual analysis, determining percentages of phasic, tonic, and “any” muscle activity in the chin, leg, and arm, which is a time-consuming process. However, automated methods for submentalis chin muscle tone analysis have been shown to be a faster and equally sensitive and specific method for diagnosis of RBD.[10, 15, 19-21]

Previous studies determining muscle activity percentage cutoff values for RBD have focused on patients having Parkinson's disease with RBD (PD-RBD), or combined analyses of both PD-RBD and idiopathic RBD (iRBD) patients.[11, 15, 22] We recently analyzed both visual and automated RSWA methods, reporting cutoff values for percent muscle activity in the submentalis muscle (SM) and anterior tibialis (AT) muscle, and the automated REM atonia index (RAI) for the SM for PD-RBD patients with or without comorbid obstructive sleep apnea (OSA),[15] and also introduced a method for measuring SM and AT phasic muscle burst durations which improved sensitivity and specificity for RBD diagnosis.[15] While our methods are similar to those published by other groups, we utilize a phasic muscle activity duration of 0.1-14.9 seconds, instead of 0.1-5 seconds, in order to include phasic muscle bursts lasting longer than 5 seconds in our duration analysis.[13-15, 18] We aimed to determine manual and automated RSWA cutoff values in iRBD patients with or without OSA and to determine whether phasic burst duration measurement also improved diagnostic accuracy in iRBD patients.

Methods

A total of 45 consecutive patients seen between 2008 and 2013 at the Mayo Clinic Center for Sleep Medicine were selected for retrospective RSWA analysis from our polysomnographic (PSG) database. The patient group included 15 antidepressant-naïve iRBD patients meeting the ICSD-2 criteria for RBD diagnosis without any clinical signs of parkinsonism or dementia.[23] No RBD patients were receiving medications known to affect REM sleep muscle tone at the time of PSG. The control group included 30 antidepressant-naïve sleep-disorder controls matched for age, sex, and apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). Twenty-two of the control patients were reported in a previous study.[15] Twenty-six (87%) of the control patients were referred for a sleep consultation for evaluation of sleep-disordered breathing. Ten (67%) iRBD patients were referred for dream-enactment behavior, whereas in 5 (33%) patients, a clear history of dream enactment was elicited during clinical interview at presentation with other primary sleep complaints of disordered breathing (3 patients) or insomnia/excessive daytime sleepiness (2 patients). Chart review was performed for age, sex, and other clinical and demographic factors. iRBD patients and controls with an AHI >25/hour or a total REM time of less than 5 minutes were excluded from analysis. Five (33%) iRBD patients and 6 (20%) controls underwent split-night sleep studies (which require an AHI ≥5 per hour during the first two hours of sleep, followed by a positive airway pressure titration trial during the second half of the night).[24] For RSWA analysis, each half of split-night PSGs were combined for whole-night analysis, which we have previously shown to be highly similar in RSWA amounts to whole-night PSGs.[15] The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Polysomnographic Recordings

Video PSG recordings were conducted on a 16-channel Nicolet NicVue digital system with general acquisition methods as previously published.[15] Electromyogram (EMG) recording included SM, bipolar linked AT electromyography in both RBD patients and controls and extensor digitorum communis (EDC) for RBD patients only. Our laboratory only routinely records EDC when RBD is suspected, so we were not able to analyze EDC muscle activity in controls. We chose to analyze the SM, and AT for generalizability of our data to other clinical sleep practices given that these muscles are commonly sampled in clinical sleep laboratories. 30-second PSG epochs were used for standard sleep stage scoring.[25] Because RSWA often does not allow scoring of REM sleep by established rules, the occurrence of the first REM in the EOG channel was used to determine the onset of REM,[15, 26] with end of REM sleep determined when either no REMs were detected in 3 consecutive minutes or when an awakening, K complexes, or spindles were observed. SM and AT EMG channels were amplified at 5 μV/mm with low- and high-frequency filters set at 10 and 70 Hz, respectively, with a sampling rate of 500 Hz, as previously established methods.[15]

Analysis of REM Sleep Muscle Activity

The reference background EMG amplitude during REM sleep varied from 0.5-2.0 μV in all subjects. Quantitative analysis of EMG activity was performed utilizing HypnoLab sleep scoring software (ATES Medica Labs, Verona, Italy). Overall tonic, phasic, and “any” (either tonic, phasic, or both forms of muscle activity occurring within the same mini-epoch) percent muscle activity were manually scored by previously published methods.[11-13, 15, 27] Phasic and “any” percent muscle activity were also calculated separately for SM and AT muscles. In addition, the duration of each phasic muscle burst during REM sleep was directly measured, and those bursts fulfilling scoring standards[13, 15, 17, 25] were individually recorded for each muscle, resulting in an overall average phasic muscle burst duration. Any 3-second mini-epoch containing a breathing-related, snoring-related, or spontaneous arousal was excluded from final analysis. [15]

Phasic muscle activity was defined as having duration between 0.1-14.9 seconds with an amplitude of greater than four times the lowest background muscle activity voltage. Return of muscle activity to background for at least 200 msec was considered to be the end of a phasic burst. Percent phasic muscle activity was calculated based on the number of 3-second mini-epochs containing phasic muscle activity divided by the total number of 3-second mini-epochs during REM sleep. Similarly, percent “any” muscle activity was calculated as the number of 3-second mini-epochs containing phasic muscle activity plus the number of 3-second mini-epochs containing tonic muscle activity divided by the total number of REM 3-second mini-epochs (any 3-second mini-epoch containing both phasic and tonic muscle activity was only counted once to avoid artificially inflated muscle activity percentages).[15]

Thirty-second epochs were used to score tonic muscle activity in both the SM and AT muscles. An epoch was considered positive for tonic activity if greater than 50% of the epoch (i.e., 15 or more seconds in duration), had muscle activity continuously greater than double the background EMG, or ≥10 μV.[13-15, 17, 25] Tonic muscle activity percentage was calculated as the total number of positive 30-second epochs divided by the total number of analyzable 30-second REM sleep epochs. “Phasic-on-tonic” muscle activity (i.e., concurrent phasic and tonic muscle activity occurring within the same 3-second mini-epoch) was scored positively in addition to underlying tonic activity only if the overlying phasic burst was greater than twice the background tonic EMG activity within that same 3-second mini-epoch. [11, 15]

The RAI for the SM muscle was calculated using HypnoLab sleep scoring software.[10] Prior to RAI analysis, 30-second epochs containing a breathing-related artifact, snoring, or arousal were excluded and the SM signal was notch filtered at 60 Hz and rectified.[10, 15]

RSWA was also analyzed using AASM criteria for excessive phasic muscle activity, defined as a 30-second epoch containing five or more 3-second mini-epochs containing phasic muscle activity within them.[25] This definition was used to generate AASM phasic percent muscle activity for the SM and AT muscles individually and combined.

Scorers of RSWA were blinded to patient group and had high inter-rater reliability with a ĸ coefficient of 0.897. ĸ coefficients were calculated according to previously published methods.[11, 15]

Statistical Analysis

Clinical, demographic, and PSG data are presented as means, standard deviations, and frequencies. Quantitative variables were analyzed using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests while chi-square tests were used to analyze categorical variables with JMP statistical software (JMP, Version 9. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Relationships between clinical independent variables and dependent tonic, phasic, and “any” muscle activity, RAI, and phasic muscle burst duration were analyzed utilizing multivariable linear or logistic regression. A post-hoc Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple tests, setting experiment-wise alpha level at p <0.01. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated for combined phasic, tonic, and “any” percent muscle activities as well as phasic and “any” percent muscle activities for SM and AT muscles. In addition, ROC curves were calculated for phasic muscle burst durations in both muscles. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each analysis, and cutoff diagnostic threshold values were chosen that yielded the highest combined sensitivity and specificity distinguishing RBD from OSA controls. A reclassification analysis was also performed to determine the impact of phasic burst duration consideration on the diagnosis of RBD.[15]

Results

Clinical and Demographic Data

Of the 45 patients, 38 (85%) were male with an average age of 66.5 (range 33-87) years. RBD was diagnosed at an average age of 63.8±6.0 (range 51-73) years with an average symptom duration of 5.7±3.1 (range 1-10) years (Table 1). Six (40%) RBD patients had a diagnosis of OSA (AHI≥5) compared to 11 (37%) controls. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and body mass index (BMI) did not differ between iRBD patients and controls. No patient had a diagnosis of narcolepsy. PSG variables were no different between groups (Supplemental Table 1). A mean of 1267.4±431.9 mini-epochs were analyzed per patient.

Table 1. Patient demographics and RSWA analysis.

| iRBD | Controls | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Age | 66.8±5.1 | 66.1±13.5 | 0.44 |

|

|

|||

| Gender (M/F) | 13/2 | 25/5 | 0.77 |

|

|

|||

| ESS | 9.7±3.9 | 8.5±5.3 | 0.46 |

|

|

|||

| BMI | 29.3±4.2 | 27.8±4.45 | 0.43 |

|

|

|||

| % ME Excluded | 10.4±7.0 | 7.3±5.5 | 0.16 |

|

|

|||

| Any EMG % | 62.8±13.9 | 22.2±12.8 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| Phasic EMG % | 55.1 ±11.2 | 22.2±12.8 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| #SM + AT Tonic EMG % | 14.1±14.2 | 0.02±0.12 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| Any SM % | 41.8±23.6 | 4.3±3.2 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| Phasic SM % | 33.8±17.1 | 4.3±3.2 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| Any AT % | 34.9±17.7 | 18.9±13.3 | 0.004 |

|

|

|||

| Phasic AT% | 34.5±17.6 | 18.9±13.3 | 0.004 |

|

|

|||

| SM duration (sec) | 1.2±0.38 | 0.48±0.21 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| AT duration (sec) | 1.1±.0.39 | 0.47±0.20 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| RAI | 0.62±0.2 | 0.94±0.04 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| AASM SM | 33.3±21.2 | 1.05±1.5 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| AASM AT | 33.1 ±25.6 | 11.3±16.1 | 0.002 |

|

|

|||

| AASM Combined | 61.8±18.4 | 14.1±16.4 | <0.0001 |

|

|

|||

| Any EDC % | 30.2±16.3 | N/A | N/A |

|

|

|||

| Phasic EDC % | 27.3±13.8 | N/A | N/A |

|

|

|||

| EDC duration (sec) | 1.10±0.27 | N/A | N/A |

AT tonic contributed to 1% of total tonic muscle activity so it was combined with SM tonic muscle activity;

ESS=Epworth Sleepiness Score; BMI=body mass index; SM=submentalis muscle; AT=anterior tibialis muscle; RAI=REM atonia index; AASM =American Academy of Sleep Medicine defined criteria for RSWA; EDC=extensor digitorum communis; ME = 3 second mini-epochs

RSWA Analysis

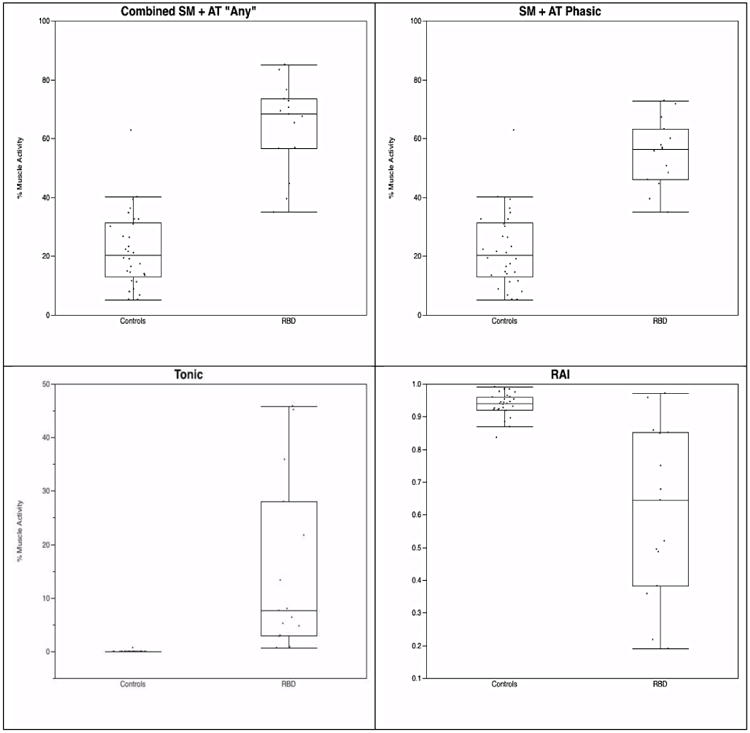

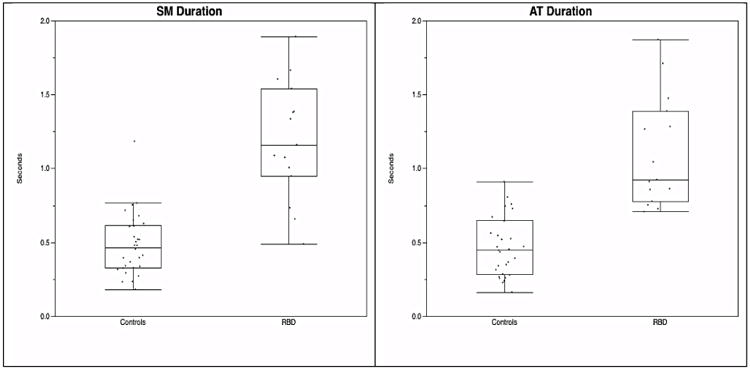

All measures of RSWA were significantly greater in iRBD patients compared with controls (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2) with only RBD diagnosis remaining associated with increased RSWA when adjusted for age, sex, periodic limb movement index (PLMI), and REM AHI in regression analyses. Longer RBD symptom duration was unassociated with longer SM duration (p=0.09). iRBD patients had similar levels of phasic muscle activity in both the SM and AT (33.9±17.8, 34.5±17.7) in comparison to controls, who had significantly more phasic muscle activity in AT than SM (18.9±13.3 vs. 4.3±3.2, p<0.0001). AT tonic muscle activity contributed to less than 1% of total tonic muscle activity, and there were no differences in levels of SM + AT tonic muscle activity vs. SM tonic muscle activity alone in iRBD patients or controls.

Figure 1. Combined, tonic RSWA muscle activity and REM atonia index.

Figure 2. SM and AT durations.

SM=submentalis muscle; AT=anterior tibialis muscle

Analysis of phasic muscle activity utilizing 3-second mini-epoch scoring or AASM 30-second epoch scoring yielded similar amounts of RSWA for iRBD patients in SM+AT combined (55.1±11.2 vs. 61.8±18.4, p=0.19), SM (33.8±17.1 vs. 33.3±21.2, p=0.95), and AT (34.5±17.6 vs. 33.1±25.6, p=0.47). However, 3-second vs. 30-second phasic muscle activity percentages differed significantly within the control group: SM + AT combined (22.2±12.8 vs. 14.1±16.4, p=0.003), SM alone (4.3±3.2 vs. 1.05±1.5, p<0.0001), and AT alone (18.9±13.3 vs. 11.3±16.1, p=0.002).

A cutoff in 3-second mini-epochs of 39.5 for both SM + AT combined “any” and phasic muscle activity was 93% sensitive and 93% specific for RBD diagnosis. A tonic muscle activity cutoff of 0.70 was 100% sensitive and 97% specific. For SM “any” muscle activity, a 3-second mini-epoch cutoff of 19.7 yielded 87% sensitivity and 100% specificity, while a SM phasic cutoff of 15.8 resulted in the same sensitivity and specificity. AT was the least sensitive and specific muscle with a cutoff of 29.7 yielding sensitivity and specificity of 67% and 83%, respectively. An RAI of 0.86 was 87% sensitive and 96% specific for RBD. SM duration of 0.66 seconds was 93% sensitive and 83% specific for RBD, while an AT duration of 0.71 seconds yielded 100% sensitivity and 80% specificity (Table 2).

Table 2. Cutoff values for RBD diagnosis.

| Cutoff Rates | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| SM+AT “Any” % | 39.5 | 93% | 93% | 0.980 |

|

|

||||

| SM+AT Phasic % | 39.5 | 93% | 93% | 0.970 |

|

|

||||

| Tonic % | 0.70 | 100% | 97% | 0.998 |

|

|

||||

| SM “Any” % | 19.7 | 87% | 100% | 0.933 |

|

|

||||

| SM Phasic % | 15.8 | 87% | 100% | 0.933 |

|

|

||||

| AT “Any” % | 29.7 | 67% | 87% | 0.769 |

|

|

||||

| AT Phasic % | 29.7 | 67% | 83% | 0.767 |

|

|

||||

| SM Duration (sec) | 0.66 | 93% | 83% | 0.942 |

|

|

||||

| AT Duration (sec) | 0.71 | 100% | 80% | 0.958 |

|

|

||||

| RAI | 0.86 | 87% | 96% | 0.891 |

|

|

||||

| AASM SM+AT % | 36.1 | 93% | 93% | 0.962 |

|

|

||||

| AASM SM % | 8.7 | 87% | 100% | 0.900 |

|

|

||||

| AASM AT % | 22.7 | 67% | 87% | 0.771 |

SM=submentalis muscle; AT=anterior tibialis muscle; RAI=REM atonia index; AASM =American Academy of Sleep Medicine defined criteria for RSWA; AUC=area under curve

A 30-second (AASM rules) epoch cutoff for combined SM + AT phasic muscle activity of 36.1 was 93% sensitive and 93% specific for RBD diagnosis. An AASM SM cutoff of 8.7 was 87% sensitive and 100% specific, whereas AASM AT was less sensitive with a cutoff of 22.7, yielding 67% sensitivity and 87% specificity (Table 2). All sensitivities and specificities were increased when combining percent muscle activity cutoffs with phasic muscle burst durations in reclassification analysis (Table 3).[15]

Table 3. Adjusted sensitivity and specificity combining phasic and “any” percent muscle activity with phasic muscle durations.

| Muscle Combinations | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| “Any” + SM Duration | 100% | 100% |

| Phasic + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| “Any” + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| Phasic + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| Individual Muscles | ||

| SM “Any” + SM Duration | 93% | 100% |

| SM “Any” + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| SM Phasic + SM Duration | 93% | 100% |

| SM Phasic + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AT “Any” + SM Duration | 100% | 97% |

| AT “Any” + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AT Phasic + SM Duration | 100% | 97% |

| AT Phasic + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| RAI + SM Duration | 93% | 96% |

| AASM Combined + SM Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AASM Combined + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AASM SM + SM Duration | 93% | 100% |

| AASM SM + AT Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AASM AT + SM Duration | 100% | 100% |

| AASM AT + SM Duration | 100% | 100% |

SM=submentalis muscle; AT=anterior tibialis muscle; RAI=REM atonia index; AASM =American Academy of Sleep Medicine defined criteria for RSWA

Discussion

We determined highly sensitive and specific RSWA diagnostic cutoff values for iRBD patients that were quite similar to our previously published values for PDRBD patients, and which can be applicable in clinical patient populations undergoing split-night polysomnography for diagnosis and treatment of co-morbid OSA.[11, 15, 22] In addition, we also replicated the importance of considering phasic muscle burst durations toward improving sensitivity and specificity for RBD diagnosis, with similar cutoff values (SM: 0.65 seconds in PD-RBD and 0.66 seconds in iRBD; AT: 0.79 seconds in PD-RBD and 0.71 seconds in iRBD).[15] There was a weak association between SM duration and disease length, indicating longer RSWA phasic burst duration could be a biomarker for distinguishing an underlying neurodegenerative etiology in RBD patients. In addition, quantitative RSWA measurement of phasic muscle activity and burst duration could be useful in determining whether patients with iRBD or incidentally elevated RSWA without dream enactment are at risk for developing future overt neurodegeneration, as has been suggested by a novel longitudinal pilot study of patients presenting with isolated RSWA from Innsbruck, which demonstrated phenoconversion to clinical RBD in 7% and presence of at least 1 neurodegenerative biomarker in 71.4%.[28] This hypothesis requires testing in prospective longitudinal cohort studies,[15, 18, 27] to distinguish specific patterns of RSWA in different RBD patient populations and controls.

RSWA has been shown to vary substantially within individuals between different nights,[9, 29] as well as between individuals,[29, 30] and over the time course of underlying RBD disease duration and type (i.e., whether idiopathic or symptomatic).[18, 27, 31] Our cutoff values for iRBD patients are highly similar to those that we and others have previously reported in PD-RBD patients.[11, 15, 22] This, along with recent data analyzing RSWA in psychiatric RBD patients compared with iRBD and PD-RBD patients,[16] suggests that most adult RBD patients have a common underlying RSWA pathophysiologic mechanism and are likely undergoing a similar synuclein-mediated neurodegenerative process, with most variability explainable by the factor of temporal disease duration and variation in sampling at different time points in the disease process.[16]

Our patient demographics and frequency of OSA (40%) are similar to those of the typical antidepressant-naïve RBD population. [4, 5, 15, 32, 33] RBD patients were similar to controls with regard to demographics, clinical factors including sleepiness, and PSG variables, indicating a relatively normal sleep drive in iRBD patients compared with PD-RBD patients, who generally report significant sleepiness.[15, 34] We purposefully matched AHI between groups, which explains why we did not find differences in apnea severity between RBD patients and controls, as had been noted in a previous report that found RBD patients had less severe OSA than patients without RBD.[35]

Comparing the utility of 3-second mini-epoch score cutoffs with 30-second AASM epoch scoring yielded relatively similar cutoff values for RBD diagnosis in SM+AT phasic muscle activity (39.5% vs. 36.1%), with more variation in SM (15.8% vs. 8.7%) and AT (29.7% vs. 22.8%) phasic muscle activity cutoffs, albeit with similar sensitivities and specificities. In addition, the amount of phasic RSWA in the individual SM and AT muscles varied between 3-second mini-epochs and 30-second epoch methods only in controls. These differences suggest that the 30-second AASM method may be useful in patients having a large (and abnormal) amount of RSWA but could miss subtle cases and lead to more variable RSWA estimates in patients with lower amounts of RSWA.

Phasic RSWA was also greater in the AT compared with the SM in controls, consistent with previous studies that also found a lower sensitivity and specificity for RBD diagnosis using the AT muscle alone.[11, 15] We have also previously found that AT RSWA levels are higher in men and with advancing age in a large cohort of control subjects without dream enactment,[36] suggesting that the influences of age and sex could explain differences in RSWA values between these muscles.

Comorbidities such as peripheral neuropathy or restless legs syndrome, which occurred in 27% of controls, could contribute to increased RSWA in the AT of controls, making it a less specific muscle for RBD diagnosis. Other nocturnal movement disorders such as excessive fragmentary myoclonus may be partially responsible for elevation of AT muscle activity in our control patients.[37] However, fragmentary myoclonus is by definition shorter than 150 ms,[37] and average AT phasic muscle burst duration was 470 ms in controls, indicating that fragmentary myoclonus was unlikely to be responsible for increased AT RSWA in our controls.

We routinely review each PSG prior to scoring RSWA in order to identify and remove any 3-second mini-epochs that contain muscle activity that is related to snoring, breathing-related events, and arousals.[15] This is a crucial step for both manual and automated RSWA scoring, so that muscle activity related to arousals or disordered breathing events is rigorously excluded from RSWA analysis. Artifact exclusion is essential when evaluating REM sleep muscle tone for iRBD diagnosis, to ensure that exclusion of physiologic muscle activity related to arousal (and that is not related to RSWA pathophysiology per se) is achieved. Arousal related muscle activity must be appropriately excluded from the determination of RSWA muscle activity percentages, so as to avoid falsely positive diagnoses of RBD. Rigorous artifact rejection prior to automated computerized scoring has been shown to reduce the amount of false positive RSWA by as much as 40%, when compared to RSWA determined by computerized scoring alone without artifact rejection.[21]

Our study has several limitations. Given that our sample was drawn from a single tertiary care sleep center, it is likely to be subject to referral and sampling biases. However, our iRBD cohort had similar age, gender, and clinical characteristics to other published series of RBD patients, suggesting that it is reasonably representative of iRBD patients encountered in clinical practice. In addition, we included patients who received split-night polysomnograms and included REM sleep PLM-like movements in our RSWA analyses. Six control patients and 6 iRBD patients underwent split-night PSG. We have previously shown that combining each half of a split-night study for RSWA analysis yields similar results as full-night PSG studies, and that CPAP therapy has little to no effect on RSWA.[15] Eight control patients had a total sleep periodic limb movement index of >50; however, PLMI was not associated with RSWA. The consistency of our RSWA cutoffs to our previous[18] and other studies,[11] and the difficulty in distinguishing REM PLM-like activity from true PLMS of NREM sleep, argues that this approach is practical and sound. Six of our iRBD patients had an AHI >5, raising the possibility of pseudo-RBD.[38] However, all but two of these patients (who had an AHI of 6 and 10 with CPAP titration) had an AHI of < 5 during CPAP titration, allowing for normalization of REM sleep muscle tone that may have been related to sleep-disordered breathing and accurate RSWA analysis; and all iRBD patients continued to exhibit dream enactment behaviors following successful treatment of their OSA.[38] In addition any 3-second mini-epoch that contained arousal-related or sleep-disordered breathing artifact was removed prior to analysis.

The SINBAR group has found upper limb muscles such as the flexor digitorum superficialis and the biceps brachii to be the most specific muscles for a diagnosis of RBD. Since our center only routinely records upper limb EMG from the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) in patients having a clinical suspicion for RBD, we were unable to compare arm muscle activity between RBD patients and controls in the current study.[11] Finally, we were unable to review video-PSG in correlation with RSWA in this retrospective study. However, previous studies utilizing video-PSG have found that most clinical manifestations of RBD are detected when analyzing the mentalis and limb muscles, indicating that video review may not be absolutely essential to the diagnosis of RBD. [11, 13] Furthermore, dramatic or complex, “scenic” type (i.e., elaborate or seemingly purposeful voluntary movement) DEBs often do not occur during overnight study in the sleep laboratory even in two consecutive nights, whereas RSWA is relatively stable with only minor night to night variability,[9, 39] suggesting that quantitative RSWA analysis has a greater practical diagnostic yield for RBD.

While experienced expert sleep neurologists can often accurately diagnose RSWA by subjective visual review alone, we recommend that quantitative RSWA analyses be used to complement a purely subjective visual review when diagnostic uncertainty still prevails, given the important prognostic implications of making an accurate RBD diagnosis. Tonic RSWA of 0.7% and “any” or phasic 39.5% RSWA cut-offs for the combined submentalis and anterior tibialis muscles had maximal diagnostic yield in our analyses, although SM 15.8% phasic or 19.7% “any” muscle activity also had excellent AUC values, and even average phasic burst duration over 0.66-0.71 seconds in SM or AT performed comparably, suggesting that measurement of average phasic burst durations alone may be sufficient to make a RBD diagnosis, although this will require further prospective validation. An automated RAI cutoff of 0.86 was only slightly less accurate than the visual method, suggesting the RAI may be an excellent screening tool, with more labor and time intensive visual quantitative analysis reserved for difficult cases, or in those RBD patients who have predominantly abnormal limb muscle activity and who lack significant tone elevations in the SM muscle. In our current practice, we reserve arm EMG recordings of the EDC or flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) for clinically suspected RBD, although the ICSD-3 has suggested that the SINBAR approach of recording combined SM and FDS arm EMG should be the preferred approach, and we plan to additionally validate arm muscle RBD diagnostic yield once we have a sufficient number of controls without RBD for analysis.

Given the comparability of our diagnostic RSWA cut-offs with previously published data [11, 15, 17], we favor the use of 3 second rather than 30 second (AASM) epoch scoring, since 3 second epoch scorings appear to produce more reliable and consistent RSWA calculations across different quantitative RSWA studies, probably due to the data reduction necessary to exclude artifacts and loss of viable and validly scorable 3 second miniepochs within overall 30 second epochs; that is, when rigorously excluding artifacts to avoid scoring “falsely positive” RSWA muscle activity (when using a 30 second epoch approach), it is necessary to exclude entire 30 second epochs that contain one or more mini-epochs with disordered breathing, snoring, or arousal related artifacts, leading to the omission and loss of many valid, scorable 3 second miniepochs from the calculated percentages.

Conclusion

Our method of measuring REM muscle activity and RAI, along with the addition of phasic muscle burst duration, yielded accurate diagnosis in iRBD patients with and without OSA. Our study is amongst the first that focuses on iRBD patients, and our iRBD cutoff values were highly similar to those determined for PD-RBD, indicating that idiopathic and symptomatic RBD patients are likely undergoing a similar neurodegenerative process, but are being sampled at different time points along the disease course. Our diagnostic RSWA cutoff values provide useful data to help physicians more accurately diagnose RBD in a clinical sleep medicine practice utilizing split-night polysomnography and conventional SM and AT lead placements, an important advance for clinical scoring since OSA is a common comorbidity in iRBD patients.[15, 32, 40] Future studies are planned to determine whether RSWA measures, particularly phasic muscle burst duration, may be a biomarker to predict phenoconversion to overt neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We determined visual and automated REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) diagnostic cut-offs for idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (iRBD) patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) during split-night polysomnography.

Combining analysis of phasic muscle activity burst durations with standard visual and automated methods improved sensitivity and specificity for iRBD diagnosis.

iRBD RSWA cutoffs were similar to those previously determined for PD-RBD, possibly indicating a similar underlying neurodegenerative process.

Our diagnostic RSWA cutoff values provide useful data to help physicians more accurately diagnose RBD in a clinical sleep medicine practice utilizing split-night polysomnography and conventional submentalis and anterior tibialis EMG lead placements.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by a Mayo Clinic Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Grant Award from the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG016574), and the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosures: Study Funding: Supported by a Mayo Clinic Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Grant Award from the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG016574), and the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01.

No off-label medication use.

SJ McCarter reports no disclosures. He is responsible for study concept/design, acquisition and interpretation of data, and authorship of manuscript.

EK St. Louis reports that he receives research support from the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (CCaTS), supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01, and from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Grant Award from the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG016574). He is responsible for study concept/design, acquisition and interpretation of data, and authorship of manuscript.

DJ Sandness reports no disclosures. He is responsible for analysis of data and critical review of manuscript for content.

EJ Duwell reports no disclosures. He is responsible for analysis of data and critical review of manuscript for content.

PC Timm reports no disclosures. He is responsible for analysis of data and critical review of manuscript for content.

BF Boeve reports that he is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Cephalon, Inc., Allon Pharmaceuticals, and GE Healthcare. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009). He has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology. He receives research support from the National Institute on Aging [P50 AG16574 (Co-Investigator), U01 AG06786 (Co-Investigator), RO1 AG32306 (Co-Investigator)] and the Mangurian Foundation. He is responsible for critical review of manuscript for content.

MH Silber reports no disclosures. He is responsible for critical review of manuscript for content.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:15–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Silber MH, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as an early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12:182–92. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0253-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schenck CH, Boeve BF, Mahowald MW. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder or dementia in 81% of older males initially diagnosed with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): 16year update on a previously reported series. Sleep Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson EJ, Boeve BF, Silber MH. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in 93 cases. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 2):331–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bliwise DL, Rye DB. Elevated PEM (phasic electromyographic metric) rates identify rapid eye movement behavior disorder patients on nights without behavioral abnormalities. Sleep. 2008;31:853–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns JWCF, Little RJ, Angell KJ, Gilman S, Chervin RD. EMG variance during polysomnography as an assessment for REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2007;30:1771–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consens FB, Chervin RD, Koeppe RA, Little R, Liu S, Junck L, et al. Validation of a polysomnographic score for REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2005;28:993–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cygan F, Oudiette D, Leclair-Visonneau L, Leu-Semenescu S, Arnulf I. Night-tonight variability of muscle tone, movements, and vocalizations in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:551–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferri R, Manconi M, Plazzi G, Bruni O, Vandi S, Montagna P, et al. A quantitative statistical analysis of the submentalis muscle EMG amplitude during sleep in normal controls and patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frauscher B, Iranzo A, Gaig C, Gschliesser V, Guaita M, Raffelseder V, et al. Normative EMG values during REM sleep for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2012;35:835–47. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frauscher B, Iranzo A, Hogl B, Casanova-Molla J, Salamero M, Gschliesser V, et al. Quantification of electromyographic activity during REM sleep in multiple muscles in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2008;31:724–31. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iranzo A, Frauscher B, Santos H, Gschliesser V, Ratti L, Falkenstetter T, et al. Usefulness of the SINBAR electromyographic montage to detect the motor and vocal manifestations occurring in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2011;12:284–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapierre O, Montplaisir J. Polysomnographic features of REM sleep behavior disorder: development of a scoring method. Neurology. 1992;42:1371–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.7.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Duwell EJ, Timm PC, Sandness DJ, Boeve BF, et al. Diagnostic Thresholds for Quantitative REM Sleep Phasic Burst Duration, Phasic and Tonic Muscle Activity, and REM Atonia Index in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder with and without Comorbid Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep. 2014;37:1649–62. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Sandness DJ, Arndt K, Erickson MK, Tabatabai G, et al. Antidepressant Therapy Increases REM Sleep Muscle Tone in Patients with and without REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Sleep. 2014;38:907–17. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montplaisir J, Gagnon JF, Fantini ML, Postuma RB, Dauvilliers Y, Desautels A, et al. Polysomnographic diagnosis of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2044–51. doi: 10.1002/mds.23257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Rompre S, Montplaisir JY. Severity of REM atonia loss in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder predicts Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;74:239–44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ca0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferri R, Gagnon JF, Postuma RB, Rundo F, Montplaisir JY. Comparison between an automatic and a visual scoring method of the chin muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep Med. 2014;15:661–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer G, Kesper K, Ploch T, Canisius S, Penzel T, Oertel W, et al. Quantification of tonic and phasic muscle activity in REM sleep behavior disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;25:48–55. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e318162acd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frauscher B, Gabelia D, Biermayr M, Stefani A, Hackner H, Mitterling T, et al. Validation of an integrated software for the detection of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2014;37:1663–71. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferri R, Fulda S, Cosentino FI, Pizza F, Plazzi G. A preliminary quantitative analysis of REM sleep chin EMG in Parkinson's disease with or without REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2012;13:707–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medicine AAoS. Diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd. 2005. American Academy of Sleep Medicine: International classification of sleep disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khawaja IS, Olson EJ, van der Walt C, Bukartyk J, Somers V, Dierkhising R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of split-night polysomnograms. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:357–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iber C, A IS, Chesson AJ, Quan S. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specification. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahowald MW, S C. REM sleep parasomnias. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders Company; 2005. pp. 897–916. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iranzo A, Ratti PL, Casanova-Molla J, Serradell M, Vilaseca I, Santamaria J. Excessive muscle activity increases over time in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2009;32:1149–53. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.9.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefani A, Gabelia D, Hogl B, Mitterling T, Mahlknecht P, Stockner H, et al. Long-Term Follow-up Investigation of Isolated Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Without Atonia Without Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder: A Pilot Study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1273–9. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferri R, Marelli S, Cosentino FI, Rundo F, Ferini-Strambi L, Zucconi M. Night-tonight variability of automatic quantitative parameters of the chin EMG amplitude (Atonia Index) in REM sleep behavior disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:253–8. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Lam SP, Ho CK, Li AM, Tsoh J, Mok V, et al. Diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder by video-polysomnographic study: is one night enough? Sleep. 2008;31:1179–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chahine LM, Kauta SR, Daley JT, Cantor CR, Dahodwala N. Surface EMG activity during REM sleep in Parkinson's disease correlates with disease severity. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarter SJ, Boswell CL, St Louis EK, Dueffert LG, Slocumb N, Boeve BF, et al. Treatment outcomes in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14:237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Ettinger MG, Mahowald MW. Chronic behavioral disorders of human REM sleep: a new category of parasomnia. Sleep. 1986;9:293–308. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbott RD, Ross GW, White LR, Tanner CM, Masaki KH, Nelson JS, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and subsequent development of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;65:1442–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183056.89590.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, Ho CK, Lam V, et al. Amelioration of obstructive sleep apnea in REM sleep behavior disorder: implications for the neuromuscular control of OSA. Sleep. 2011;34:909–15. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Sandness DJ, Boeve BF, Silber MH. Greatest Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Atonia Loss Occurs in Men and Older Age. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 2014;1:733–8. doi: 10.1002/acn3.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frauscher B, Kunz A, Brandauer E, Ulmer H, Poewe W, Hogl B. Fragmentary myoclonus in sleep revisited: a polysomnographic study in 62 patients. Sleep Med. 2011;12:410–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iranzo A, Santamaria J. Severe obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea mimicking REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2005;28:203–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolitho SJ, Naismith SL, Terpening Z, Grunstein RR, Melehan K, Yee BJ, et al. Investigating the night-to-night variability of REM without atonia in Parkinson's disease. Sleep Med. 2015;16:190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Boswell CL, Dueffert LG, Slocumb N, Boeve BF, et al. Factors Associated with Injury in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.