Abstract

To address the combined importance of fathers and neighborhoods for adolescent adjustment, we examined whether associations between fathers' parenting and adolescents' problem behaviors were qualified by neighborhood adversity. We captured both mainstream (e.g., authoritative) and alternative (e.g., no-nonsense, reduced involvement) parenting styles and examined parenting and neighborhood effects on changes over time in problem behaviors among a sample of Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads (N = 462). Compared to their counterparts in low-adversity neighborhoods, adolescents in high-adversity neighborhoods experienced greater initial benefits from authoritative fathering, greater long-term benefits from no-nonsense fathering, and fewer costs associated with reduced involvement fathering. The combined influences of alternative paternal parenting styles and neighborhood adversity may set ethnic and racial minority adolescents on different developmental pathways to competence.

Keywords: neighborhoods, fathers, parenting, problem behaviors, Mexican-origin

Over the last decade, the number of studies that have documented associations between parent socialization and adolescent development among U.S. racial and ethnic minority group members (“minorities”) has increased substantially (see Chao & Otsuki-Clutter, 2011 for a review). Also during this period, parenting researchers have documented the unique contributions that fathers make to development (Simpkins, Fredricks, & Eccles, 2015), especially during the transition to adolescence (Zeiders et al., in press), when the development of problem behaviors is a salient concern (Galambos, Barker, & Almeida, 2003). Meanwhile, neighborhood scholarship has documented the critical role that neighborhood adversity plays in qualifying the effects of parenting (mostly maternal) on adolescent problem behaviors (Leventhal, Dupéré, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). These three trends have likely stimulated qualitative research that has focused on minority (mostly African American) fathers' parenting in adverse neighborhoods (e.g., Doyle et al., 2015; Threlfall, Seay, & Kohl, 2014). The lack, however, of longitudinal studies documenting the combined influences of paternal parenting and neighborhood adversity on the development of problem behaviors among minority adolescents is viewed as a major gap in the literatures on fathering and adolescent development (Cabrera et al., 2014).

In the current study we sought to address gaps in the literature by examining the degree to which neighborhood adversity qualified the effects of fathers' parenting on the development of problem behaviors form early to middle adolescence. We examined the associations between paternal parenting styles (e.g., authoritative) and neighborhood adversity in early adolescence (5th grade) with longitudinal trajectories of problem behaviors (i.e., internalizing and externalizing) across adolescence (i.e., from 5th grade to10th grade) in a sample of Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads. The developmental timeframe includes key transitions from elementary to middle and high school (Eccles & Midgley, 1989), a timespan over which parenting effects may wane (Steinberg, 2008) and neighborhoods become increasingly salient contexts of development (Leventhal et al., 2009). People of Mexican origin comprise the largest subgroup (63%) of U.S. Latinos (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011) and Mexican-origin Latinos are highly likely to raise their children in two-parent, father-present households (Suro et al., 2007). The fathers in these families are notably involved and influential (Coltrane, Parke, & Adams, 2004; Parke et al., 2004). Further, because Mexican-origin Latino residential fathers are prevalent across a wide range of socioeconomic (Lopez & Velasco, 2011) and neighborhood (Roosa et al., 2009) contexts, they are an ideal population to study the combined influence of fathers and neighborhoods on adolescents' problem behaviors.

Paternal Parenting Effects on Adolescent Problem Behaviors Across Neighborhoods

One approach to documenting associations between parent socialization and adolescent development is to examine the effects of parenting styles on adolescents' problem behaviors (Moilanen, Rasmussen, & Padilla-Walker, 2015; Varela et al., 2004). The predominant parenting styles frameworks (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983), which characterize parents along responsiveness (acceptance without harshness) and demandingness (consistent discipline with monitoring) dimensions (Simons & Conger, 2007), classifies parents as either authoritative (high responsiveness and demandingness), authoritarian (low responsiveness and high demandingness), indulgent (high responsiveness and low demandingness), or neglectful (low responsiveness and demandingness). The authoritative style is considered the gold-standard in parenting, in part because it is associated with optimal problem behavior trajectories during adolescence (Galambos et al., 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999). Much of the longitudinal work documenting associations between parenting styles and problem behaviors, however, (a) excludes, or only includes a small proportion of, racial or ethnic minority group members; (b) excludes fathers, or combines mothers' and fathers' scores into a single parenting style assessment; and (c) does not consider that extra-familial contexts may qualify the effect of parenting on problem behaviors (Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999; Williams et al., 2009). Consequently, well-documented associations between parenting styles and adolescent problem behaviors (Galambos et al., 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999) may not generalize to minority fathers and adolescents, or across levels of neighborhood adversity.

Minority fathers and adolescents

Minority parents, including Latino fathers, employ diverse parenting styles. Research shows that some of these parenting styles conform to the predominant frameworks, but others do not (Domenech-Rodriguez et al., 2009; Kim, Wang, Orozco-Lapray, Shen & Murtuza, 2013). First, minority parents disproportionately face environmental stressors and deleterious contexts that influence parenting, and are, in part, a product of their minority and gendered social positions (García Coll et al., 1996). For example, being Latino (relative to being non-Latino White) was associated with higher exposure to discrimination (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000) and with residential segregation into low-quality neighborhoods (Alba et al., 2014). Further, being a Latino man (relative to being a Latina woman) was associated with longer sustained residence in low-quality neighborhoods (Sampson & Sharkey, 2008). Second, minority parents endorse diverse heritage cultural beliefs that influence parenting. For example, in the context of higher endorsement of heritage cultural beliefs, Mexican-origin fathers have been found to be less likely (than their lower-endorsement counterparts) to display reduced levels of responsiveness and demandingness toward their adolescents (White, Zeiders, Gonzales, Tein, & Roosa, 2013). In a study that compared Mexican-origin fathers and mothers of adolescents, among the families that endorsed the highest levels of heritage cultural beliefs, fathers engaged in higher levels of responsive and demanding parenting behaviors than mothers (Updegraff, Perez-Brena, Baril, McHale, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012). Overall, environmental demands associated with fathers' minority and gendered social positions combine with heritage cultural belief systems to influence paternal parenting (Cabrera et al., 2014; García Coll et al., 1996). Consequently, research on the associations between parenting and adolescent adjustment must recognize the range of parenting styles employed by minority fathers, including styles that do not conform to the predominant frameworks (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

One previously documented nonconformity relates to parenting disruptions. Disruptions to effective parenting occur when environmental stressors, ones commonly experienced by ethnic minority group members (García Coll et al., 1996) and Latino males (Sampson & Sharkey, 2008), cause problems in parenting, including lower levels of responsive and demanding behaviors (Conger et al., 2010; White, Liu, Nair, & Tein, 2015). It does not follow, however, that these lower levels of responsiveness and demandingness are necessarily so low as to be characteristics of neglectful (Maccoby & Martin, 1983) fathering. Indeed, prior work shows that, despite their minority and gendered social positions, Latino and Mexican-origin fathers did not display the low levels of responsiveness and demandingness consistent with the neglectful parenting style (Domenech-Rodriguez et al., 2009). Instead, reduced involvement fathering, characterized by lower levels of responsive and demanding behaviors, may be the common response to such stressors (Conger et al., 2010; White et al., 2013). Compared to mothers, Mexican-origin fathers have been shown to be especially susceptible to these disruptions (White, Roosa, Weaver, & Nair, 2009).

The second type of nonconformity to the predominant parenting styles frameworks relates to parenting adaptations. Parenting adaptations are aimed at promoting minority adolescent competencies within the context of extant environmental demands and affordances (Fuller & García Coll, 2010; García Coll et al., 1996). For example, no-nonsense parenting, which combines high levels of demandingness and acceptance with elevated levels of harshness, is not recognized by the predominant frameworks (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Yet, no-nonsense parenting has been actively theorized in research on African American families (Brody & Flor, 1998), empirically identified among Mexican-origin fathers (but not mothers; White et al., 2013), and may offer a culturally-situated parallel to some of the alternative parenting styles employed by other ethnic minority parents, including fathers (Kim et al., 2013). For Mexican-origin fathers' (but not mothers; White et al., 2013), no-nonsense parenting may represent a culturally-informed adaptation to environmental demands encountered, for example, in the context of discrimination and long-term residential segregation (Finch et al., 2000; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008).

Together, fathers' minority and gendered social positions and heritage cultural beliefs produce diversity in parenting styles that (a) may not conform to the predominant dimensionality and frameworks and (b) may be different from mothers' parenting styles. Person-centered analytic techniques (Berman, 2001) have been effective at capturing the wide range of parenting styles employed by ethnic minority parents, including parenting disruptions and adaptations, in prior works (Kim et al., 2013; White et al., 2013). Prior works also suggest that it may be important, in parts due to their minority and gendered social positions (García Coll et al., 1996) and to diversity in parenting roles within minority families (Updegraff et al., 2012), to examine paternal parenting effects specifically. Research that has combined maternal and paternal scores may have produced an operationalization of parenting that was inaccurate at both the level of the family system and the parent-adolescent dyad because mothers and fathers may approach parenting differently (Cabrera et al., 2014; Simons & Conger, 2007). Research that has combined maternal and paternal parenting into the same models may have masked the important and potentially distinct contributions that fathers make to development (Simpkins et al., 2015).

Neighborhood Adversity

Though contemporary perspectives recognize that associations between parent socialization and adolescent outcomes are likely to vary across diverse levels of environmental adversity (Del Giudice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, 2011), including neighborhood adversity (García Coll et al., 1996), associations between parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories have commonly been studied without consideration of the neighborhood environment. In this work (which has been based on predominant perspectives and has not considered minority fathers' parenting disruptions or adaptations) researchers generally find that authoritative parenting (vs. neglectful parenting) is associated with lower levels of internalizing and externalizing among youths, and that youths of authoritarian or indulgent parents usually fall somewhere in the middle of the other two groups (see Luyckx et al., 2011 for a review). It is critical to advance beyond this work by simultaneously considering the range of parenting styles employed by minority fathers (including reduced involvement and no-nonsense parenting) and actively theorizing the meaning and consequences of diverse paternal parenting styles across diverse neighborhood environments.

Neighborhood adversity can qualify the effects of parent socialization on adolescent development in multiple ways. Mainstream perspectives on adverse neighborhood environments have advanced a tripartite classification of the ways in which relations between parenting and problem behaviors are qualified by neighborhood adversity: (a) amplified advantages effects, when the benefits of positive parenting are greatest for adolescents in low-adversity neighborhoods; (b) family compensatory effects, when the benefits of positive parenting are greatest for adolescents in high-adversity neighborhoods; and (c) amplified disadvantages effects, when the costs of negative parenting are greatest for adolescents in high-adversity neighborhoods (Roche & Leventhal, 2009). Recent work, based largely on culturally and contextually informed developmental theory (Del Giudice et al., 2011; García Coll et al., 1996), suggests that a fourth classification is needed: adaptive parenting effects, when the influence of parenting characterized as costly in mainstream settings (e.g., higher harsh parenting in low-adversity neighborhoods) proves non-costly or beneficial in non-mainstream settings (e.g., in high adversity neighborhoods; White et al., 2015).

Only a few studies have examined neighborhood adversity as a moderator of the associations between parenting styles and problem behaviors. First, Meyers and Miller (2004) found that authoritativeness was concurrently associated with fewer problem behaviors, but only when (predominately European American and African American) adolescents lived in high-adversity neighborhoods (consistent with family compensatory effects). Conversely, Simons et al., (2005) found that authoritative caregiving was most beneficial at reducing African American adolescents' problem behaviors in low-adversity neighborhoods (consistent with amplified advantages effects). One study that was not exclusively based on the predominant frameworks found that less involved parenting displayed amplified disadvantages effects on problem behaviors (Brody et al., 2003). Still, these studies focused heavily on mothers, non-Latinos, and the predominant parenting styles frameworks (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Consequently, they did not investigate fathers' parenting or no-nonsense fathering.

Given the limited focus on (paternal) parenting style by neighborhood adversity interactions in the extant literature, additional insight may be gained from research on specific parenting behaviors. Like extant research on parenting styles, however, few studies have focused specifically on fathers' parenting behaviors. Further, the pattern of findings is mixed and somewhat suggestive of ethnic and racial group differences (Dearing, 2004). Maternal acceptance behaviors demonstrated family compensatory effects in sample of African Americans (Dearing, 2004) and amplified advantages effects in a pan-racial-ethnic sample (Wickrama & Bryant, 2003). A prospective study that focused specifically on Mexican-origin fathers and adolescents, however, found that paternal acceptance displayed amplified advantages effects (White et al., 2015). Parental (combining mothers and fathers) monitoring has displayed family compensatory effects among diverse groups, including Latinos (Beyers et al., 2003; Rankin & Quane, 2002; Roche & Leventhal, 2009). Qualitative work suggests that monitoring may be an especially important component of the fathering repertoire for minority fathers living in adverse circumstances (Dumka et al., 2009; Letiecq & Koblinsky, 2004), but no quantitative studies have examined the association between paternal monitoring and adolescent problem behavior trajectories across diverse neighborhoods. Harsh maternal parenting demonstrated adaptive parenting effects in an African American and pan-Latino sample of mother-adolescent dyads (Roche et al., 2011), but, in a Mexican-origin sample, paternal (and not maternal) harsh parenting displayed adaptive parenting effects (White et al., 2015). Though evidence is scarce, and few studies have focused on Mexican-origin Latinos or fathers, the current pattern of findings favors amplified advantages effects of authoritative fathering, amplified disadvantages effects for reduced involvement fathering, and adaptive parenting effects of no-nonsense fathering among Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads.

Current Study

The aim of the current study was to examine associations between diverse paternal parenting styles and Mexican-origin adolescent problem behavior trajectories across diverse levels of neighborhood adversity. Based on our review of minority fathers' parenting, along with developmental theory highlighting the importance of parents' minority and gendered social positions for parent socialization (García Coll et al., 1996), we relied on a set of Mexican-origin fathers' parenting styles identified in prior work, including authoritative, reduced involvement, and no-nonsense fathering (White et al., 2013). We examined whether the relation between a given parenting style and problem behavior trajectory was qualified by neighborhood adversity. We hypothesized that authoritative fathering would display amplified advantages effects, reduced involvement fathering would display amplified disadvantages effects, and no-nonsense fathering would display adaptive parenting effects. Though adolescent sex did not influence the parenting style employed by Mexican-origin fathers (White et al., 2013), there are well-documented differences in rates of problem behaviors between boys and girls (Galambos et al., 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011). Similarly, there are differences in rates of problem behaviors between Mexico- versus U.S.-born adolescents (Gonzales, Germán, & Fabrett, 2012). Therefore, we controlled for adolescent sex and nativity in all analyses.

Method

Data were from the first three waves (W1, 5th grade; W2, 7th grade; and W3, 10th grade) of a longitudinal study of the influence of culture and context in the lives of Mexican-origin adolescents and their families (Roosa et al., 2008). Beginning in the fall semester of 2004, Mexican-origin students and their families (N = 749 families) were recruited from 5th grade rosters of schools that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities. Eligible families met the following criteria: (a) there was a 5th grade youth who attended a sampled school, was not severely learning disabled, and was the biological child of a Mexican-origin mother and Mexican-origin father; (b) the Mexican-origin biological mother lived with the youth; and (c) no step-father figure was living in the household. Accordingly, eligible families did not have to be two-parent households with a co-resident biological father. Only 570 families were two-parent, father-present households; the remaining 179 families were single-parent, female-headed households. Fathers in the 570 two-parent households were eligible to participate in the study. Other biological fathers were excluded because they are less common among Mexican-origin Latinos (Suro et al., 2007) and extra-household fathers would likely have experienced difficulty answering questions on parenting. The current study focused on the subset of 462 father-adolescent dyads that participated at W1 and had data on parenting (81.1% of eligible father-adolescent dyads).

Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the first author's university. Complete research procedures are published elsewhere (Roosa et al., 2008). The research team first identified economically, culturally, and socially diverse communities served by 47 public, religious, and charter schools throughout a large southwestern metropolitan area. We sent recruitment materials home with all 5th graders in these schools (approximately 86% of 5th graders and their families returned materials and expressed interest in the study) and screened interested families for eligibility. Of all eligible families, 73% (N = 749) were interviewed. All study materials were available in English and Spanish. Each family member completed computer assisted personal interviews and was paid $45, $50, and $55 for participation at W1, W2, and W3, respectively.

Our prior work demonstrates that the current sample of father-adolescent dyads (N = 462) is similar on family income, child nativity, father nativity, and child gender to the 108 (18.9%) families in which there was an eligible father that chose not to participate (White et al., 2013). Female adolescents comprised 48.1% of the sample. The mean age at 5th grade was 10.8 years (SD = 0.47). Most of the adolescents (66.9%) were born in the U.S. (the remaining in Mexico) and most (81.8%) were interviewed in English (the remaining in Spanish). Most (79.7%) fathers were born in Mexico, and most (76.4%) completed the interview in Spanish. On a scale of 1 ($0,000 - $5,000) to 20 ($95,001+), average annual family income was 7.76, with 7 representing $30,001 - $35,000, and 8 representing $35,001 - $40,000. Families' residential addresses were assigned to their respective census tracts, an operationalization of the neighborhood environment that offers a comparison to the reviewed work (e.g., Dearing, 2004; Simons et al., 2005; Wickrama & Bryant, 2003). The geographic size of census tracts closely approximates the average size of resident-defined neighborhoods, but census tracts may not correspond perfectly to residents' perceived neighborhood boundaries (Coulton, Korbin, Chan, & Su, 2001). The current sample of father-adolescent dyads came from 126 census tracts at W1. Poverty rates ranged from 0.8% to 68.5% and male unemployment rates ranged from 0.0% to 32.0%.

Measures

Covariates (W1)

Data on a series of demographic characteristics were collected, including adolescent gender adolescent nativity (66.9% U.S.-born; 33.1% Mexico-born), and father reports on annual family income (1 = $0,000 - $5,000 to 20 = $95,001 +).

Parenting styles (W1)

Fathers' parenting styles were previously obtained from a person-centered latent profile analysis (LPA) on four parenting behaviors. Acceptance (8 items, e.g., your father understood your problems and worries), harsh parenting (8 items, e.g., your father spanked or slapped you when you did something wrong), and consistent discipline (8 items, e.g., when you broke a rule, your father made sure you received the punishment he said you would get) were from the Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (Schaefer, 1965). Monitoring (8 items, e.g., your father knew who your friends were) was from Small and Kerns (1993). The scales' cross-language measurement properties (including item invariance and construct validity equivalence) have been establish elsewhere in the literature (author5). In the current study alphas for the four parenting scales ranged from .70 to .88. Response options were 1 (almost never or never), 2 (once in a while), 3 (sometimes), 4 (a lot of the time), and 5 (almost always or always). As in prior work (Simons & Conger, 2007), acceptance and low harsh parenting operationalized the responsiveness dimension; monitoring and consistent discipline operationalized the demandingness dimension.

LPA allowed parenting styles to emerge from the data that were both consistent with and different from the predominant frameworks. Both fathers' self-reports and adolescent-reports on fathers' behaviors were available, and prior work suggests low levels of parent-child agreement on parenting behaviors (author8), so we estimated the profiles separately for father and youth reports on fathers' behaviors. The two LPA solutions were viewed as conceptual replications; similar study results across the two LPA solutions increases both internal and external validity of study findings. LPA details are reported elsewhere (author1). Based on optimal model fit and interpretability we used the 2-class LPA solution for fathers' self-reports and the 3-class LPA solution for the adolescent-reports on fathers' behaviors. A reproduction of the profile solutions is presented in Supplemental Materials Figure A. Both solutions produced an authoritative profile with high acceptance, monitoring, and consistent discipline and low levels of harsh parenting (63.6% and 70.7% of fathers in the father-report and adolescent-report solutions, respectively). Both solutions also produced a reduced involvement profile (36.4% and 17% of fathers in the father-report and adolescent-report solutions, respectively). Reduced involvement patterns mirrored the authoritative profile, but with somewhat reduced levels of acceptance, consistent discipline, and monitoring. The adolescent-report solution produced a third profile, no-nonsense parenting (12.3% of fathers). These fathers had levels of acceptance, consistent discipline, and monitoring that were comparable to authoritative fathers, but they also had elevated levels of harshness. As shown in Supplemental Materials Figure A, the mean on harsh parenting in the no-nonsense group corresponded to using harsh parenting sometimes, whereas the means on harsh parenting in both the authoritative and reduced involvement groups corresponded to using harsh parenting only once in a while. Our prior work established the construct validity of the profiles (author1) and, as discussed there, our profiles offered replications of extant work on Latino parenting (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009; Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008). Perhaps the most notable replication was to Domenech Rodríguez et al.'s (2009) work because their approach, like ours, did not rely on analytical techniques (e.g., sample-based cut-offs) that forced parents into one of the four predominant parenting styles (author1). In their sample of predominantly Mexican-origin Latino parents they also failed to identify groups of neglectful or authoritarian fathers.

Neighborhood adversity (W1)

Neighborhood adversity was assessed using 2000 tract-level census data. We standardized and summed data on the percent of (a) families below the poverty level, (b) unemployed males, (c) single-parent households with a female head, and (d) households with public assistance (Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murry, 2002). Chronbach's alpha was .88 and there was variability in adversity across the 126 neighborhoods in the sample (x̄ = 0.00,SD = 3.44)

Adolescents' problem behaviors (W1, W2, W3)

The computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas, 2004) was used to assess adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Mothers and adolescents were administered the DISC independently. Internalizing symptoms were defined as the sum of the symptom counts for generalized anxiety, major depression, and social phobia; externalizing symptoms were defined as the sum of the symptom counts for oppositional defiance disorder, conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Conger et al., 2002; Cosgrove et al., 2011). Mother reports and adolescent reports were aggregated using standard scoring algorithms to maximize test-retest reliability and criterion validity (Shaffer et al., 2004) and reduce shared method variance.

Analytic Strategy

We relied on longitudinal growth modeling to estimate trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms separately using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). In all models, the time metric used was grade (the 5th, 7th, and 10th grades corresponded to approximately 11, 13, and 16 years in age, respectively) with the anchor point as 5th grade (W1). Additionally, a multilevel model was used to take into account the nesting within neighborhoods at 5th grade. The proportions of missing data on our study variables ranged from 0% to 14.72% (see Supplemental Materials Table A). We used maximum likelihood estimation to deal with missing data (Enders, 2010), allowing the full sample to be included in the analyses. We utilized the robust adjustment of the maximum likelihood estimator to adjust the standard errors of path coefficients for non-normality (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012).

Prior to specifying the analytic strategy, we had to run preliminary growth models to determine the functional form of the growth trajectories (not shown). The first models (one for internalizing and one for externalizing) assumed that there was no quadratic term but allowed the intercept and the slope terms to vary across individuals and across neighborhoods. The second models included a quadratic term fixed to be the same across individuals and the same across neighborhoods, but allowed the intercept and the slope terms to vary across individuals and across neighborhoods. Using the deviances of the two models, we calculated likelihood ratio test statistics, which were non-significant (Δχ2 (1) = .29, p = .59 for internalizing; and Δχ2 (1) = .07, p = .79 for externalizing). This indicated that adding the fixed quadratic terms (which were non-significant in both models) did not improve model fit. Thus, we continued with models assuming random intercept and slope terms, but no quadratic growth term.

There were four sets of analyses conducted, including estimating the association between two problem behavior trajectories (internalizing symptom trajectories and separate externalizing symptoms trajectories) and two parenting styles solutions (the two-profile father-report solution and the separate three-profile adolescent-report solution). Parenting styles were dummy-coded, with authoritative being the reference group in all models. The growth factors (i.e., intercept and slope) of adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms were regressed on these parenting dummy variables and the covariates (see Supplemental Materials Figure B). The model intercept represented the 5th grade levels of problem behaviors for the reference group; the linear slope represented the growth rate from 5th to 10th grade for the reference group. To examine whether neighborhood adversity qualified the association between parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories we regressed (a) the random intercept and random slope terms of the reference group and (b) the random effects of the parenting dummy variables on the intercept and slope terms (at the within-neighborhood level) on neighborhood adversity (at the between-neighborhood level). Such effects indicated whether (a) the intercept and slope of the reference group were associated with neighborhood adversity and (b) the effect of each parenting dummy variable on the intercept and slope varied by neighborhood adversity (i.e., moderation effects). If a parenting dummy variable effect on the intercept or slope term was not moderated by neighborhood adversity, nor did it have significant residual variance across neighborhoods, then it was treated as a fixed effect. In contrast, if a parenting dummy variable effect on the intercept or slope term was found to be moderated by neighborhood adversity, we conducted post-hoc comparisons using the MODEL CONSTRAINT command. This allowed us to produce the average intercept and slope parameters for both the target parenting style (e.g. no-nonsense) and the reference group (i.e., authoritative) at high (+ 1 SD) and low (- 1 SD) neighborhood adversity (Cohen et al., 2003). We then tested whether these parameters differed significantly at high and low neighborhood adversity.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We performed preliminary attrition analyses to examine whether families who participated at W2 and W3 versus those that did not were different on W1 adolescent demographic (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), father demographic variables (i.e., age, generational status), and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. All comparisons were non-significant.

We provide two sets of descriptive statistics in on-line Supplemental Materials. First, the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations of study variables at the individual level are presented in Supplemental Materials Table A. Second, we conducted preliminary longitudinal growth modeling to describe the problem behavior trajectories associated with each parenting style. In these analyses, we did not consider neighborhood adversity, thus they offer a more direct comparison to prior work documenting associations between parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories during adolescence (Galambos, Barker, & Almeida, 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999). The intercept and slope terms of the reference group (authoritative) and the parenting dummy variable effects were allowed to vary across neighborhoods (i.e., random effects). (Note: to achieve convergence in the internalizing model with the adolescent-report solution, the reduced involvement dummy variable effects had to be fixed to be the same across neighborhoods.) The parenting dummy variable effects represented differences in intercept or linear slope terms between a given parenting style (e.g., reduced involvement) and the reference group (i.e., authoritative). Based on results from these models, average problem behavior intercept and slope parameters for each parenting style were computed and represented graphically (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

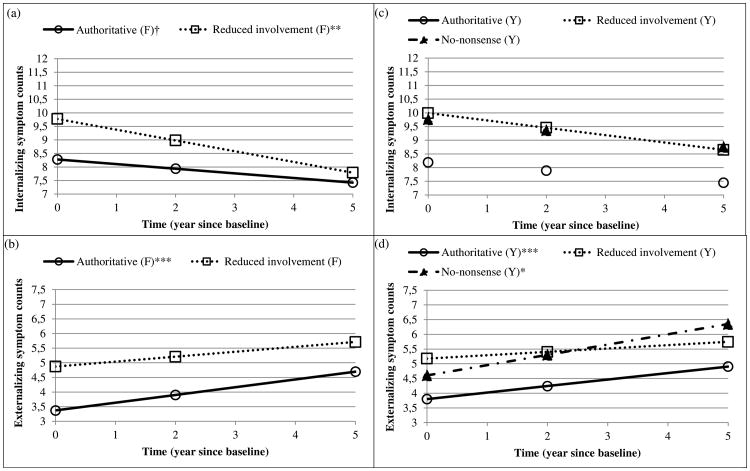

As shown in the preliminary models describing the problem behavior trajectories associated with each parenting style (Supplemental Materials Table B), in both the father-report and adolescent-report internalizing models, adolescents with reduced involvement fathers had significantly higher initial levels of internalizing symptoms compared to those with authoritative fathers [Bfather = 1.50 (.50), p < .01; Badolescent = 1.80 (.60), p < .01)]. Adolescents with both types of fathers, however, experienced statistically similar [Bfather = -.23 (.14), ns; Badolescent = -.12 (.19), ns] declines in internalizing symptoms across adolescence. In both the father-report and adolescent report externalizing models, adolescents with reduced involvement fathers had significantly higher initial levels of externalizing symptoms compared to those with authoritative fathers [Bfather = 1.50 (.49), p < .01; Badolescent = 1.38 (.58), p < .05)]. Adolescents with both types of fathers, however, experienced statistically similar [Bfather = -.10 (.13), ns; Badolescent = -.11 (.15), ns] growth in externalizing across adolescence: positive slopes that were not significantly different from one another. In the youth-report models, adolescents with no-nonsense fathers had internalizing and externalizing intercepts and slopes that were not statistically different [Badolescent = 1.57 (.87), p = .07 for internalizing intercept differences; B = .81 (.59), ns for externalizing intercept differences; Badolescent = -.05 (.19), ns for internalizing slope differences; B = .13 (.17), ns for externalizing slope differences] from those observed for adolescents with authoritative fathers. For descriptive purposes, the internalizing and externalizing trajectories associated with each parenting style are displayed in Figure 1a – d.

Figure 1.

Average trajectories associated with different father-report parenting styles on (a) internalizing symptoms and (b) externalizing symptoms, and average trajectories associated with different adolescent-report parenting styles on (c) internalizing symptoms and (d) externalizing symptoms. Note: † p < .10; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01; *** p ≤ .001. Y = youth report solution; F = father report solution.

Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Problem Behavior Trajectories Across Neighborhoods

Our analyses examined whether the effects of a given parenting style dummy variable on adolescents' problem behavior trajectories (including the intercepts and slopes) were moderated by neighborhood adversity. The effects of neighborhood adversity on the random intercept and slope terms were for the reference group, adolescents with authoritative fathers. If the effects of the parenting dummy variables on the intercept or slope were significantly predicted by neighborhood adversity, then the difference between a given parenting style and the reference group on (a) the 5th grade symptom levels or (b) the growth rate of symptoms would be different across diverse levels of neighborhoods adversity. In these cases, we conducted post-hoc comparisons to see whether the intercept or slope parameters of the corresponding parenting styles were different in high- vs. low-adversity neighborhoods.

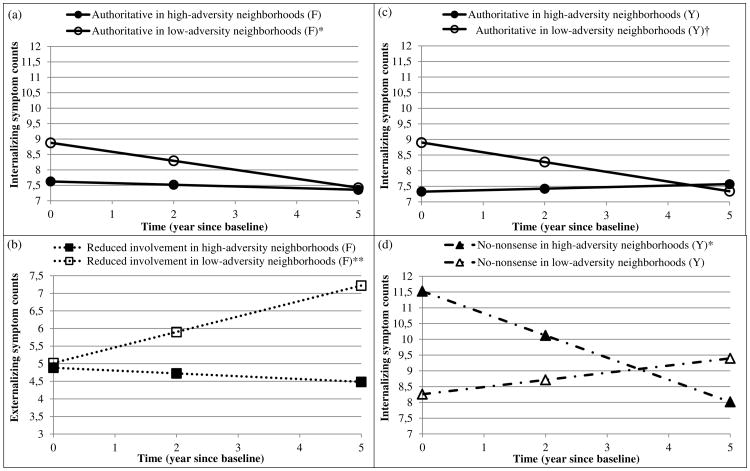

Father-report parenting styles

As show in the top half of Table 1 for the internalizing model, for adolescents with authoritative fathers, the internalizing intercept was significantly associated with neighborhood adversity [B = -.18 (.08), p < .05] but the slope was not [B = .04 (.03), ns]. Post-hoc comparisons showed that initial levels of internalizing among those with authoritative fathers were lower in high-adversity neighborhoods (B = 7.63 (0.40), p < .001) than in low-adversity neighborhoods (B = 8.88 (0.44), p < .001), and the difference between these two intercepts was significant (B = -1.25 (0.57), p < .05; Figure 2a). The effects of the reduced involvement dummy variable on the internalizing intercept and slope terms were not moderated by neighborhood adversity and the residual variance across neighborhoods was not significant. Regardless of neighborhood adversity, the internalizing intercept for the reduced involvement group was always higher than that of the authoritative group [B = 1.53 (.48), p < .01]. The slope difference was non-significant. Thus these effects were fixed to be the same across neighborhoods and had no average effects estimated at the between-neighborhood level. Overall, authoritative fathering had greater initial internalizing benefits for adolescents living in high-adversity neighborhoods.

Table 1. Model results describing neighborhood adversity as a qualifier of parenting effects on problem behavior trajectories.

| Internalizing model Coefficient (SE) | Externalizing model Coefficient (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Father report on parenting styles | ||

| Within-neighborhood | ||

| 5th grade level | ||

| Youth gender | -.42 (.49) | 1.53 (.46)*** |

| Youth nativity | .28 (.56) | .11 (.43) |

| Family income | -.05 (.07) | .10 (.04)* |

| Reduced involvement | 1.53 (.48)** | 1.55 (.50)** |

| Linear slope | ||

| Youth gender | -.20 (.13) | -.31 (.12)** |

| Youth nativity | -.11 (.14) | .12 (.12) |

| Family income | .02 (.02) | .00 (.01) |

| Reduced involvement | -.23 (.14) | -- |

| Between-neighborhood | ||

| Avg. 5th grade level | ||

| Intercept | 8.25 (.31)*** | 3.40 (.30)*** |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -.18 (.08)* | -.02 (.05) |

| Residual variance | .72 (2.31) | .11 (.77) |

| Avg. linear slope | ||

| Intercept | -.17 (.10)† | .26 (.07)*** |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | .04 (.03) | .03 (.02)† |

| Residual variance | .07 (.05) | .03 (.03) |

| Avg. reduced involvement effect on 5th grade level | ||

| Intercept | -- | -- |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -- | -- |

| Residual variance | -- | -- |

| Avg. reduced involvement effect on linear slope | ||

| Intercept | -- | -.08 (.13) |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -- | -.10 (.03)*** |

| Residual variance | -- | .06 (.07) |

| Youth report on father parenting styles | ||

| Within-neighborhood | ||

| 5th grade level | ||

| Youth gender | -.29 (.52) | 1.32 (.48)** |

| Youth nativity | .51 (.57) | .06 (.40) |

| Family income | -.05 (.06) | .08 (.04)† |

| Reduced involvement | 1.86 (.60)** | 1.32 (.56)* |

| No-nonsense | -- | .75 (.58) |

| Linear slope | ||

| Youth gender | -.28 (.13)* | -.32 (.11)** |

| Youth nativity | -.19 (.15) | .11 (.12) |

| Family income | .02 (.02) | .00 (.01) |

| Reduced involvement | -.13 (.18) | -- |

| No-nonsense | -- | .15 (.17) |

| Between-neighborhood | ||

| Avg. 5th grade level | ||

| Intercept | 8.12 (.36)*** | 3.80 (.29)*** |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -.23 (.10)* | .00 (.06) |

| Residual variance | .01 (1.91) | .13 (.58) |

| Avg. linear slope | ||

| Intercept | -.13 (.11) | .21 (.07)*** |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | .05 (.03) | .01 (.02) |

| Residual variance | .003 (.06) | .03 (.03) |

| Avg. reduced involvement effect on 5th grade level | ||

| Intercept | -- | -- |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -- | -- |

| Residual variance | -- | -- |

| Avg. no-nonsense effect on 5th grade level | ||

| Intercept | 1.78 (.81)* | -- |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | .71 (.34)* | -- |

| Residual variance | 3.69 (6.36) | -- |

| Average reduced involvement effect on linear slope | ||

| Intercept | -- | -.09 (.15) |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -- | -.08 (.04)* |

| Residual variance | -- | .06 (.07) |

| Average no-nonsense effect on linear slope | ||

| Intercept | -.11 (.17) | -- |

| 5th grade neighborhood adversity | -.19 (.07)** | -- |

| Residual variance | .02 (.23) | -- |

Note. N = 462.

p < .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

Youth gender was coded 0 = female, 1 = male; youth nativity was coded 0 = US-born, 1 = Mexico-born. Reduced involvement was coded 0 = other parenting styles, 1 = reduced involvement style; no-nonsense was coded 0 = other parenting styles, 1 = no-nonsense style; the reference group, authoritative style, gets a score of zero on both dummy variables. Effects of parenting dummy variable on the intercept or slope term that were not significantly moderated by neighborhood adversity and did not have significant residual variances across neighborhoods were fixed to be the same across neighborhoods. Such effects were instead estimated at the within-neighborhood level, and had no average effects estimated at the between-neighborhood level.

Figure 2.

Average trajectories of (a) internalizing symptoms for father reported authoritative, (b) externalizing symptoms for father reported reduce involvement, (c) internalizing symptoms for youth reported authoritative, and (d) internalizing symptoms for youth reported no-nonsense in high- and low-adversity neighborhoods. Note: † p < .10; * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01. Y = youth report solution; F = father report solution.

As show in the top half of Table 1 for the externalizing model, for adolescents with authoritative fathers, the slope of externalizing symptoms was marginally associated with neighborhood adversity [B =.03 (.02), p < .10] but the intercept was not [B = -.02 (.05), ns]. The difference between the slopes for adolescents with authoritative fathers in high- [B = .36 (.09), p < .001] versus low- [B = .16 (.08), p = .05] adversity neighborhoods was not significant [B = .19 (.11), p = .08]. The effect of the reduced involvement dummy variable on the slope of externalizing symptoms was moderated by neighborhood adversity [B = -.10 (.03), p < .001], but the effect of the reduced involvement dummy variable on the intercept term was not. Thus the effect of reduced involvement dummy variable on the intercept term was fixed to be the same across neighborhoods. Post-hoc comparisons showed that adolescents with reduced involvement fathers did not have a significant average linear slope of externalizing in high-adversity neighborhoods [B = -.08 (.14), ns]; in low-adversity neighborhoods they had a positive average slope [B = .44 (.17), p < .01]. The difference between these two slopes (Figure 2b) was statistically significant [B = -.52 (.21), p < .05]. Overall, adolescents with reduced involvement fathers had similar initial levels of externalizing symptoms across neighborhoods. Over time, however, only those living in low-adversity neighborhoods experienced increases in externalizing.

Adolescent-report parenting styles

As shown in the bottom half of Table 1 for the internalizing model, the intercept for the authoritative group was significantly associated with neighborhood adversity [B = -.23 (.10), p < .05] but the slope was not [B = .05 (.03), ns]. Post-hoc comparisons showed that the average internalizing intercept for authoritative was lower in high-adversity neighborhoods (B = 7.33 (0.41), p < .001) compared to low-adversity neighborhoods [B = 8.90 (0.56), p < .001]. This difference was significant (B = -1.58 (0.67), p < .05; Figure 2c). The effects of the reduced involvement dummy variable on the internalizing intercept and slope terms were not moderated by neighborhood adversity. Thus these effects were fixed to be the same across neighborhoods, and had no average effects estimated at the between-neighborhood level. The effects of the no-nonsense dummy variable on the internalizing intercept and slope terms were significantly moderated by neighborhood adversity [B = .71 (.34), p < .05, a cross-level intercept interaction; B = -.19 (.07), p < .001, a cross-level slope interaction]. Post-hoc comparisons showed that adolescents with no-nonsense fathers had a negative average slope of internalizing in high-adversity neighborhoods [B = -.70 (.31), p < .05], but a non-significant average slope in low-adversity neighborhoods [B = .23 (.29), ns]. The difference between these two slopes was significant [B = -.93 (.47), p < .05; Figure 2d]. The difference between the no-nonsense internalizing intercepts across high-adversity [B = 11.52 (1.32), p < .001] and low-adversity [B = 8.26 (1.44), p < .001] neighborhoods was not significant [B = 3.26 (2.22), ns]. Overall, authoritative fathering had greater initial internalizing benefits for adolescents living in high-adversity neighborhoods than those living in low-adversity neighborhoods. Adolescents with no-nonsense fathers had similar initial levels of internalizing across high- and low-adversity neighborhoods; over time, however, only those in high-adversity neighborhoods showed significant declines in internalizing symptoms.

As shown in the bottom half of Table 1 for the externalizing model, neither the intercept nor the slope was associated with neighborhood adversity for the authoritative group [B =.00 (.06), ns; B = .01 (.02), ns, respectively]. The effects of the no-nonsense dummy variable on the externalizing intercept and slope terms were not moderated by neighborhood adversity. The effect of reduced involvement on the intercept term was not moderated by neighborhood adversity. These effects were fixed to be the same across neighborhoods. The effect of the reduced involvement dummy variable on the slope term of externalizing symptoms was moderated by neighborhood adversity [B = -.08 (.04), p < .05]. Post-hoc comparisons showed that adolescents with reduced involvement fathers had a non-significant average slope in high-adversity neighborhoods [B = -.11 (.20), ns], but a marginally significant positive average slope in low adversity neighborhoods [B = .37 (.20), p = .06]; the difference between these slopes was marginally significant [B = -.48 (.25), p = .06]. Though the findings were only marginally significant, the pattern replicated the difference observed for reduced involvement in high- and low-adversity neighborhoods in the father-report parenting styles models (e.g., Figure 2b).

Discussion

In the current study we examined the association between Mexican-origin fathers' parenting styles and longitudinal trajectories of adolescents' problem behaviors across diverse levels of neighborhood adversity. Because fathers' parenting styles are influenced by environmental demands associated with their minority and gendered social positions and by their heritage cultural beliefs (García Coll et al., 1996), it was critical to capture the range of paternal parenting styles employed by Mexican-origin fathers. According to extant scholarship on Mexican-origin fathers' parenting (Domenech Rodriquez et al. 2009) this range has included styles that conformed to the predominant frameworks (i.e., authoritative; Bamrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin; 1983) and ones that did not (i.e., reduced involvement and no-nonsense), as well as styles that have been used by Mexican-origin fathers, but not mothers (i.e., no-nonsense fathering, author1). Because associations between parenting and adolescent development may be qualified by neighborhood adversity (Del Giudice et al., 2011; García Coll et al., 1996), it was also critical to examine the implications of neighborhood adversity for the associations between paternal parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories. We found that, compared to their counterparts in low-adversity neighborhoods, Mexican-origin adolescents in high-adversity neighborhoods experienced greater initial benefits from authoritative fathering, greater long-term benefits from no-nonsense fathering, and fewer costs associated reduced involvement fathering.

Paternal Parenting and Adolescent Problem Behavior Trajectories Across Neighborhoods

The generalizability, to minority fathers and adolescents and across neighborhoods, of extant scholarship documenting associations between parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories (Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Scaramella, Conger, & Simons, 1999; Williams et al., 2009) was uncertain. This uncertainty reflected, in part, an overemphasis on the predominant parenting styles frameworks, which did not recognize parenting disruptions and adaptations associated with fathers' minority and gendered social positions and heritage cultural beliefs (Cabrera et al., 2014; García Coll et al., 1996). It also reflected an outdated underlying assumption about the universal implications of parenting for diverse adolescents' problem behaviors (Conger et al., 2010; author2). Contemporary developmental perspectives recognize that associations between diverse parenting styles and adolescent development depend on the quality of the extant environment (Del Giudice et al., 2011; García Coll et al., 1996). Consistent with these perspectives, across all three paternal parenting styles examined herein – including authoritative fathering, no-nonsense fathering, and reduced involvement fathering – there was evidence that neighborhood adversity qualified the association between diverse paternal parenting styles and problem behavior trajectories. Those qualifications, however, were not always in the hypothesized directions.

Authoritative fathering

Authoritative fathering displayed an initial family compensatory effect on internalizing symptoms: it was most beneficial in high-adversity neighborhoods. These findings replicated across father- and adolescent-report models, and offer a replication and extension of prior work. Meyers & Miller (2004) found similar cross-sectional effects in multi-racial and ethnic sample. Given that the parenting style and initial levels of problem behaviors were assessed at the same time in the current study (5th grade), the cross-sectional finding replicates and extends their work to a sample of Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads. The initial compensatory effect, however, did not appear to extend across adolescence because neighborhood adversity did not qualify the effect of authoritative fathering on the internalizing growth rate. Fathers who are high on acceptance, consistent discipline, and monitoring and low on harshness may create a home environment in which early adolescents are able to feel safe and secure. These feelings run counter to internalizing problems (Scaramella et al., 1999). The benefits of having such a home environment may be especially critical for early adolescents in adverse neighborhoods, who may need to rely more heavily on the family (vs. the extra-familial) environment for safety and security. This compensatory effect, however, does not appear to extend to changes in internalizing symptoms across adolescence. Perhaps authoritative fathering is important for curbing early internalizing vulnerabilities. As adolescents engage in an expanding social context, however, their more direct experiences in extrafamilial neighborhood environments may become influential (Leventhal et al., 2009). Alternatively, these expanding social contexts may signal alternative paternal parenting needs (Del Giudice et al., 2011), as discussed below.

Though our results for authoritative fathering and internalizing were consistent with a family compensatory effect that has been observed in past cross-sectional work (Meyers & Miller, 2004), we had originally hypothesized that they would be consistent with an amplified advantages effect (Simons et al., 2005; author2). Simons et al. (2005) reported amplified advantage effects of authoritative parenting, but only a small proportion of fathers were included in their sample of African American caregivers. Relative to their African American counterparts, Mexican-origin families in adverse neighborhood environments are more likely to have co-resident fathers (Lopez & Velasco, 2011). It may be that the added presence of authoritative fathers in adverse neighborhood environments compensates for adversity; whereas authoritative mothering only amplifies environmental advantages. Still, [author] et al (2015) documented amplified advantages effects of paternal acceptance behaviors among Mexican-origin fathers. Though paternal acceptance, alone, may be able to amplify environmental advantages, compensating for neighborhood adversity during early adolescence may require numerous resources and paternal investments (above and beyond paternal acceptance), including responsiveness and demandingness. More research on the amplifying versus compensatory properties of paternal and maternal parenting behaviors and styles will shed light on these hypotheses.

No-nonsense fathering

Consistent with our hypothesis, no-nonsense fathering displayed adaptive parenting effects on internalizing symptom trajectories. It was associated with significant declines in adolescent internalizing symptoms only for those that lived in high-adversity neighborhoods. Our findings offer a substantial extension to prior work. First, the findings extend prior work among African American caregivers and adolescents (Brody & Flor, 1998; Brody & Murry, 2001a), which theorized that no-nonsense mothering promoted early adolescent competencies in adverse environments. Second, we previously found that Mexican-origin fathers' paternal harshness displayed adaptive parenting effects on internalizing symptoms three years later (author2), but that study was not able to examine paternal harshness vis-à-vis paternal demandingness and acceptance. Here, we empirically tested culturally and contextually informed developmental theorizing (Brody & Flor, 1998) and document that the combination of elevated paternal harshness with high acceptance and demandingness is effective at reducing Mexican-origin adolescents' internalizing symptoms in adverse neighborhoods.

Our combined internalizing findings for the authoritative and no-nonsense fathering styles in high-adversity neighborhoods offer an unexpected developmental observation. In high-adversity neighborhoods authoritative fathering was associated with the lowest levels of early-adolescent (i.e., initial) internalizing; no-nonsense fathering, however, was associated with decreases across time as youth transitioned from early to middle adolescence. It appears that the addition of elevated harshness to the parenting and neighborhood configuration worked to substantially reduce internalizing across the developmental period. Perhaps, no-nonsense fathering affects feelings of safety and security for adolescents transitioning to more autonomous stages and experiencing more independent contact with their adverse neighborhood environments. Elevated levels of paternal harshness, including punitive child management techniques and a more aggressive interactional style, may effectively shield adolescents in high-adversity neighborhoods from victimization and teach them to anticipate and adequately prepare for environmental adversity (Brody & Flor, 1998). For minority adolescents living high-adversity neighborhoods, no-nonsense fathering may meet a particular parenting need that manifests across this developmental transition. Research that can simultaneously examine changes over time in parenting styles and adolescents' problem behaviors could shed light on this hypothesis.

Contrary to our hypothesis, neighborhood adversity did not qualify the effect of no-nonsense fathering on externalizing symptom trajectories. As it concerned externalizing symptoms, adolescents with no-nonsense fathers had 5th grade levels that were statistically similar to adolescents with authoritative fathers and increases across time that were statistically similar to the increases adolescents with authoritative fathers experienced. Though neighborhood adversity did not moderate these associations, our findings that no-nonsense fathering was associated with externalizing trajectories that were the same (statistically) as the externalizing trajectories of adolescents with authoritative fathers, runs contrary to mainstream conceptualizations of elevated parental harshness (Conger et al., 2010). According to those perspectives, any elevation in paternal harshness should be associated with more externalizing problem behaviors, as both harsh parenting and externalizing behaviors reflect an aggressive style of interacting with others (Scaramella, et al., 1999). Yet we did not observe such a pattern. To the extent that a fathering style that includes elevated levels of harsh parenting does not predict higher initial levels or stronger increases (e.g., than authoritative fathering) in externalizing symptoms across a developmental period when increases are normative (Luyckx et al., 2011), it may be appropriate to conclude that no-nonsense fathering is functioning adaptively for Mexican-origin adolescents. Though neighborhood adversity does not appear to be the factor that qualifies the effects of no-nonsense fathering on externalizing symptoms, other aspects of minority adolescents' diverse ecologies may help to explain why and under what conditions no-nonsense fathering (beneficially) influences externalizing symptoms. For example, no-nonsense fathering may display adaptive parenting effects to other essential factors commonly encountered in minority adolescents' developmental niches (García Coll, et al., 1996).

Overall, these findings suggest that no-nonsense fathering may be a successful adaptation to adverse neighborhood environments and for Mexican-origin adolescents. It may be that the influences of fathers' minority and gendered social positions and heritage cultural beliefs produce parenting adaptations (García Coll et al., 1996), aimed at promoting minority adolescent competencies within the context of extant environmental demands and affordances (Fuller & García Coll. 2010). Some of these adaptions may involve diversity in parenting (maternal vs. paternal) roles (Updegraff et al., 2012). Because prior work suggests that Mexican-origin mothers did not employ this parenting style (author1), no-nonsense parenting may represent a specific paternal adaptation (reflecting Mexican-origin fathers' minority and gendered social positions and heritage cultural beliefs) aimed at promoting their adolescents' development in adverse neighborhood environments. This paternal adaptation may set Mexican-origin adolescents on different developmental pathways to competence (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). Specifically, in contrast to prior findings in mainstream developmental research (e.g., Conger et al., 2010), our results suggest that the combination of elevated paternal harshness, acceptance, and demandingness is associated with an alternative developmental trajectory in adverse neighborhood contexts and for minority adolescents. These alternative developmental trajectories included significantly decreasing internalizing behavior problems and developmentally normative changes in externalizing behavior problems.

Reduced involvement fathering

Reduced involvement fathering displayed adaptive parenting effects on externalizing symptom trajectories. Specifically, reduced involvement fathering was associated with more optimal externalizing trajectories in high-adversity neighborhoods and less optimal trajectories in low-adversity neighborhoods. This finding ran counter to our expectations that living in a high-adversity neighborhood would amplify the costs of having a father that was less-involved (Brody et al., 2003). Instead, in low-adversity (more mainstream) neighborhoods, reduced involvement fathering was associated with increases in externalizing symptoms comparable to what might generally be expected from the broader literature on neglectful parenting (Galambos et al., 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011). In high-adversity neighborhoods, reduced involvement fathering was not associated with increase in externalizing. Notably, the basic pattern of findings was replicated across the father- and adolescent-report models.

To understand this replicated pattern, it may be helpful to consider the different meanings or circumstances surrounding reduced involvement fathering in low- and high-adversity neighborhoods (Brody & Flor, 1998; Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2004). It is possible that having a less involved father – one who is not so extremely low on responsiveness and demandingness to be considered neglectful – is only costly in low-adversity neighborhood environments where the presence of fathers and norms for parental involvement may be higher (Sampson, 2001 ; Pyke, 2000). In such a context, where the fathering role carries the expectation of greater involvement (along with, perhaps, adequate resources to support involvement), reduced involvement fathering may signal an actual or perceived fathering deficit (Pyke, 2000). In contrast, it may be more normative for fathers in high-adversity, less resourced neighborhoods to experience limits vis-à-vis their parenting (author6). In the high-adversity context, then, a reduced form of paternal involvement is not interpreted as a parenting deficit and does not influence Mexican-origin adolescents externalizing symptoms. In the low-adversity context, conversely, the paternal deficit may influence adolescents to act out and display more externalizing symptoms. Both the meaning adolescents place on reduced paternal involvement (Choi et al., 2013) and the normativeness of paternal involvement (Lansford et al., 2004) across high- and low-adversity neighborhoods are important underlying mechanisms to explore in future work.

Neighborhood adversity as a qualifier of paternal parenting effects on adolescent problem behavior trajectories

Comparisons between our neighborhood adversity models and our preliminary descriptive models, which did not consider neighborhood adversity, highlight the importance of the neighborhood context for accurate predictions about the associations between diverse paternal parenting styles and adolescents' problem behavior trajectories. When we did not model neighborhood adversity, we found that authoritative fathering compared to reduced involvement fathering was associated with lower initial levels of problem behaviors (both internalizing and externalizing symptoms), but that there were no differences in changes over time in problem behaviors. This is largely consistent with prior work (Galambos et al., 2003; Luyckx et al., 2011).

Overall, in the models that did not consider neighborhood adversity, we observed some mean level differences in early adolescent problem behaviors for youths of authoritative and reduced involvement fathers, but no differences in changes across adolescence between authoritative and either of the other two groups. When we examined the effect of Mexican-origin fathers' parenting styles on problem behavior trajectories across diverse levels of neighborhood adversity, however, far more trajectory differences surfaced. Authoritative fathering demonstrated family compensatory effects on early adolescent internalizing levels. No-nonsense fathering displayed adaptive parenting effects on changes in internalizing symptoms across adolescence. Reduced involvement fathering displayed adaptive parenting effects on changes across adolescence in externalizing symptoms. The study suggests that fathers' parenting style effects on problem behavior trajectories across adolescence are substantially qualified by neighborhood adversity. Consequently, accurate predictions about the effects of minority fathers' socialization on adolescents' problem behaviors likely requires knowledge about neighborhood adversity.

Conclusions and Limitations

Our findings suggest that ethnic minority fathers may need to calibrate their parenting style to maximize their adolescents' success in diverse neighborhoods (Del Giudice et al., 2011; García Coll et al., 1996). Minority adolescents, including Mexican-origin adolescents, are adapting to different circumstances than European American adolescents. These differences certainly occur vis-à-vis neighborhood adversity (South et al., 2005), but they also occur in other ways. For example, minority adolescents (like their fathers) are developing in and adapting to different social positions, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic segregation (García Coll et al., 1996). It is important to consider that fathering that combines responsiveness and demandingness with elevated levels of harshness may be an adaptation to several aspects of minority adolescents' developmental ecologies. It is also important to consider that minority adolescents living in more mainstream, less-adverse neighborhoods may have heightened vulnerability to reduced involvement fathering. Also, because similar parenting styles may be employed by other minority groups' parents and caregivers (Brody & Flor, 1998; Kim et al, 2013), consistent with their own minority and gendered social positions, we encourage extension of this hypothesis testing to other groups.

It is necessary to view the study's contributions in light of its limitations. We tested our study hypotheses among a sample of fathers from two-parent Mexican-origin families. The focus on intact families is an important one for this population, but we strongly encourage work on other family forms. We replicated all analyses with the parenting styles solution obtained from an LPA of fathers' self-reports on acceptance, harsh parenting, consistent discipline, and monitoring and the parenting styles solution obtained from an LPA of adolescents' reports on the same behaviors. Generally, results for authoritative and reduced involvement fathering were replicated across these solutions. As discussed elsewhere (author1) and subsequently corroborated by differences between father- and adolescent-reports on fathering profiles in other minority groups (Kim at al., 2013), our father-report LPA solution did not produce a no-nonsense style. Consequently, we were unable to offer a replication of those results. Replications drawing from both multi-reporter and observational data will offer valuable extensions. Still, our results demonstrated the value of the no-nonsense style of fathering in high-adversity contexts, a finding that is theoretically consistent with prior work (Brody & Flor, 1998; author2). We operationalized the neighborhood at the level of the census tract using census data from 2000; future work will need to consider other operationalizations (e.g., block group or resident-defined; Coulton et al., 2001) and strive to minimize any time lags between census and primary data collections. Though we controlled for income and nativity status, two variables influencing neighborhood selection, only true experimental designs can eliminate selection confounds in neighborhood research (Dupere, Leventhal, Crosnoe, & Dion, 2010). In light of (a) the influence of Latino fathers' heritage values and minority and gendered social positions on their parenting styles (Alba et al., 2014; Finch et al., 2000; García Coll et al., 1996; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008; author1), as well as limitations associated with combined (with mothers) scoring (Simons & Conger, 2007) and modeling approaches (Simpkins et al., 2015), it was critical to devote attention to fathers specifically. Still, future work will need to incorporate information on the mother-adolescent and parent subsystems to inform the best and most nuanced understanding of parenting and adolescent development. Finally, though we controlled for gender differences in problem behavior trajectories, it is possible that adolescent gender is a child factor that further qualifies the nature of the parenting-by-neighborhood adversity interaction. Future work incorporating a larger sample of adolescents and neighborhoods could examine such complexities.

Our findings with Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads supports both mainstream and ethnic and racial minority developmental theories (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Del Giudice et al., 2011; García Coll et al., 1996), suggesting some potential that our hypotheses and research question could generalize to other ethnic and racial minority group members. Indeed, work with diverse ethnic and racial minority families supports the existence of alternative parenting styles (Brody & Flor, 1998; Kim et al., 2013). Also, parenting characterized by reduced levels of responsive and demanding behaviors, like reduced involvement fathering, is common among diverse families exposed to environmental stressors (Conger et al., 2010). Therefore, it is likely that the implications of fathers' diverse parenting styles for their adolescents' development of problem behaviors varies systematically as a function of neighborhood adversity in other groups. Because parenting styles combining high levels of demandingness and acceptance with elevated levels of harsh, punitive, and demeaning behaviors may be relevant to African American mothers (Brody & Flor, 1998) and Chinese American fathers (Kim et al., 2013), it is critical that practitioners working with diverse adolescents and families recognize that these parenting styles may be effective (Kim et al.2015; Roche & Leventhal, 2009), either in certain neighborhood contexts, or in the broader context of minority adolescents' ecological niches (García Coll, et al., 1996). Similarly, because reductions in responsiveness and demandingness may be common parenting responses to environmental stressors (Conger et al., 2010) that both minority and majority group members experience, it is critical that practitioners working with diverse adolescents and families carefully consider that the implications of reduced paternal involvement for adolescents' problem behaviors may be different in high- vs. low-adversity neighborhood environments. Generally, interventions designed to combat reduced involvement or no-nonsense fathering are not universally indicated.

Supplementary Material

Figure A. Original figures with profile solutions for the 2-class LPA solution for fathers' self-reports (top panel) and the 3-class LPA solution (bottom panel) for the adolescent-reports on fathers' behaviors1.

Figure B. Analytical model.

Table A. Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Study Variables at the Individual Level

Table B. Model results describing problem behavior trajectories associated with fathers' parenting styles, absent consideration of neighborhood adversity

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the families for their participation in the project. Work on this project was supported, in part, by NIMH grant R01-MH68920.

Contributor Information

Rebecca M. B. White, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics and Latino Resilience Enterprise, Arizona State University

Yu Liu, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Nancy A. Gonzales, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

George P. Knight, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Jenn-Yun Tein, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

References

- Alba R, Deane G, Denton N, Disha I, McKenzie B, Napierala J. The role of immigrant enclaves for Latino residential inequalities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2014;40:1–20. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.831549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR. A person-centered approach to adolescence: Some methodological challenges. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths' externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Flor D. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM. Sibling socialization of competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:996–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol 1: Theoretical models of human development. 6th. New York: John Wiley; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Fitzgerald HR, Bradley RH, Roggman L. The ecology of father-child relationships: An expanded model. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2014;6:336–354. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM. Self-reported parenting practices in Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers of young youths. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:354–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Otsuki-Clutter M. Racial and ethnic differences: Sociocultural and contextual explanations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Kim SY, Park IJ. Is Asian-American parenting controlling and harsh? Empirical testing of relatinhips between Korean American and Western parenting measures. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4:19–29. doi: 10.1037/a0031220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Laurence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Parke RD, Adams M. Complexity of father involvement in low-income Mexican American families. Family Relations. 2004;53:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove V, Rhee S, Gelhorn H, Boeldt D, Corley R, Ehringer M, et al. Hewitt J. Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton CJ, Korbin J, Chan T, Su M. Mapping residents' perceptions of neighborhood boundaries: A methodological note. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:371–383. doi: 10.1023/A:1010303419034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E. The Developmental implications of restrictive and supportive parenting across neighborhoods and ethnicities: Exceptions are the rule. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2004;25:555–575. [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA. The adaptive calibration model of stress responsivity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35:1562–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez M, Donovick M, Crowley S. Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process. 2009;48:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle O, Trenette CT, Cryer-Coupet Q, Nebbitt VE, Goldston DB, et al. Unheard voices: African American fathers speak about their parenting practices. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 16:274–283. doi: 10.1037/a0038730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Russell ST, Crockett LJ. Parenting styles and adolescent well-being across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, Millsap RE. Academic success of Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers' and fathers' parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles. 2009;60:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Midgley C. Stage-environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. Research on Motivation in Education. 1989;3:139–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NC. The Hispanic population: 2010 (2010 Census Briefs No C2010BR-04) Washington, DC: U. S. Census; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Belzer A, Davis C, Levine JA, Morrow K, Washington M. How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In: Wilson WJ, editor. Sociology and the public agenda. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]