Abstract

We report a case of structural valve deterioration, which occurred 7 years after aortic valve replacement in a 78-year-old male with cardiac sarcoidosis. His echocardiography showed low transprosthetic valve gradient and depressed left ventricular function. A dobutamine stress echocardiography was performed to identify his pathophysiology, and it revealed that his depressed left ventricular function was not due to cardiac sarcoidosis but to structural valve deterioration. Reoperation for structural valve deterioration was performed, and his left ventricular function recovered.

Keywords: Cardiac sarcoidosis, dobutamine stress echocardiography, low-gradient, structural valve deterioration

Introduction

Structural valve deterioration is one of the complications after bioprosthetic valve replacement. Reoperation for structural valve deterioration is recommended in symptomatic patients with high transprosthetic gradient. However, it is unclear whether to perform reoperation in asymptomatic patients with low transprosthetic gradient. Especially, in patients with depressed left ventricular function, it is important to clarify which the main cause of left ventricular dysfunction is structural valve deterioration or other factors such as cardiomyopathy.

Case Report

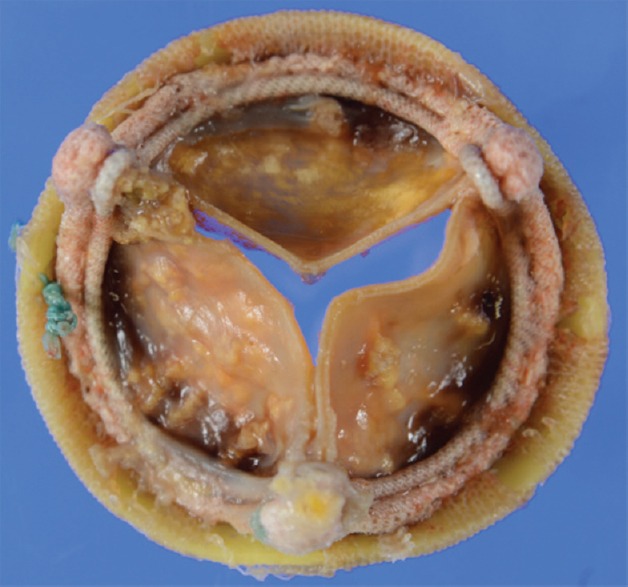

This case is a 78-year-old male who underwent aortic valve replacement with a 23 mm Carpentier-Edwards Perimount pericardial bioprosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) for aortic valve stenosis 7 years ago at another hospital. He had a medical history of sarcoidosis treated with 10 mg of prednisolone. Pulmonary sarcoidosis was diagnosed in his 50s, and cardiac sarcoidosis was diagnosed by a myocardial biopsy at the time of the previous cardiac surgery. His echocardiography showed a thinned basal interventricular septum. He had a past history of thyroid cancer, and his thyroids and parathyroids were resected at the age of 45, and then after that, he had been prescribed with levothyroxine and alfacalcidol. The echocardiography 6 years after the previous operation showed a normal opening of his prosthesis with an effective orifice area index of 0.62 cm2/m2, a mean pressure gradient of 15 mmHg, and mildly reduced left ventricular function with an ejection fraction of 43%. Although he was asymptomatic, his transthoracic echocardiography 1 year later revealed the restricted motion of the prosthetic valve leaflets, with an effective orifice area index of 0.28 cm2/m2 and a mean pressure gradient of 28 mmHg. It also revealed depressed left ventricular function with an ejection fraction of 37%, moderate mitral insufficiency, and severe tricuspid insufficiency. Considering comparably early deterioration of his bioprosthesis valve and left ventricular function, we decided to perform a dobutamine stress echocardiography to differentiate structural valve deterioration from pseudo-aortic stenosis due to cardiac sarcoidosis. At the baseline, the aortic valve peak velocity and the stroke volume index were 3.8 m/s and 31 ml/m2. At a dose of 10 μg/kg/min of dobutamine infusion, they increased to 4.4 m/s and 41 ml/m2, respectively, and the mean pressure gradient across the bioprosthesis increased to 47 mmHg, as the effective orifice area index remained small at 0.29 cm2/m2. Therefore, he was diagnosed as having structural valve deterioration of bioprosthesis at aortic position. He underwent redo aortic valve replacement with a 20 mm ATS standard mechanical valve (ATS Medical, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), mitral annuloplasty with a 26 mm Carpentier-Edwards Physio II annuloplasty ring (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA), and tricuspid annuloplasty with a 28 mm Edwards MC3 tricuspid annuloplasty ring (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). A transthoracic echocardiography at 6 months after the reoperation showed a recovery of left ventricular function with ejection fraction of 49%. Pathologic examination of the explanted prosthesis showed calcified deposit and desmoplasia in all the leaflets without an evidence of infiltration of monocyte [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Explanted prosthesis showed calcification in all the leaflets.

Discussion

We reported a rare case of low transprosthetic gradient structural valve deterioration at aortic position in a patient with cardiac sarcoidosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis occurs in perhaps 5% of patients with sarcoidosis. The principal manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis are conduction abnormalities, ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure.[1] Considering early bioprosthetic deterioration in a patient with cardiac sarcoidosis, there were three challenging points to be discussed in this case. First, it was difficult to diagnose which the main cause of depressed left ventricular function was structural valve deterioration or cardiac sarcoidosis. Second, he had no previously reported predictive factors for early bioprosthetic deterioration. Third, the optimal strategy for this case including the type of surgery and prosthesis was worth debating.

This case was low-gradient aortic stenosis, which was defined as an aortic valve area <1.0 cm2 and a mean transvalvular gradient <40 mmHg.[2] One of the diagnostic challenges in low-gradient aortic stenosis with depressed left ventricular function is to differentiate true severe aortic stenosis from pseudo-aortic stenosis. In this case, if the cause of depressed left ventricular function was structural valve deterioration, redo aortic valve replacement would be strongly recommended. On the other hand, if his depressed left ventricular function was the clinical manifestation of the cardiac sarcoidosis, the benefit of reoperation on the ventricular reverse remodeling was uncertain. A dobutamine stress echocardiography is useful to differentiate true severe aortic stenosis from pseudo-aortic stenosis in case of native aortic valve.[3] It remains unclear whether it is also useful in case of bioprosthetic valve deterioration, but it could lead us to the diagnosis of true structural valve deterioration.

Only 7 years had passed until the reoperation for structural valve deterioration in this case. The time period was relatively short in comparison with the previous reports.[4] Nollert et al. reported several risk factors of early bioprosthetic deterioration, but this case did not have any of these factors.[5] Skolnick et al. reported the association between osteoporosis and decreased progression of aortic stenosis, and speculated inhibition of valvular calcification might be due to alterations in levels of Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone.[6] On the other hand, it is reported chronic secondary hyperparathyroidism in renal failure is associated with aortic calcification. In patients with sarcoidosis, high plasma parathyroid hormone-related peptide levels are often observed. It might contribute to the hypercalcemia of sarcoidosis and act like parathyroid hormone. Therefore, the possible cause of early bioprosthesis deterioration in this case might be alfacalcidol, an analog of Vitamin D or parathyroid hormone-related protein due to sarcoidosis.

The patient was asymptomatic, but it was reasonable to perform reoperation because the structural valve deterioration caused the left ventricular dysfunction. In this case, we decided to perform surgical aortic valve replacement with mechanical valve considering his early bioprosthetic valve deterioration and the possibility of the need for another redo aortic valve replacement. However, it might be another option to perform surgical aortic valve replacement with bioprosthetic valve and transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure if necessary in the future. Future studies are warranted to determine what strategies about the optimal type of surgery and valve selection are reasonable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RS. Cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:411–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2438–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deFilippi CR, Willett DL, Brickner ME, Appleton CP, Yancy CW, Eichhorn EJ, et al. Usefulness of dobutamine echocardiography in distinguishing severe from nonsevere valvular aortic stenosis in patients with depressed left ventricular function and low transvalvular gradients. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:191–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)80078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourguignon T, Bouquiaux-Stablo AL, Candolfi P, Mirza A, Loardi C, May MA, et al. Very long-term outcomes of the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount valve in aortic position. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:831–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nollert G, Miksch J, Kreuzer E, Reichart B. Risk factors for atherosclerosis and the degeneration of pericardial valves after aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:965–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skolnick AH, Osranek M, Formica P, Kronzon I. Osteoporosis treatment and progression of aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:122–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]