Abstract

Caspases are key enzymes responsible for mediating apoptotic cell death. Across species, caspase‐2 is the most conserved caspase and stands out due to unique features. Apart from cell death, caspase‐2 also regulates autophagy, genomic stability and ageing. Caspase‐2 requires dimerization for its activation which is primarily accomplished by recruitment to high molecular weight protein complexes in cells. Here, we demonstrate that apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5/AAC11) is an endogenous and direct inhibitor of caspase‐2. API5 protein directly binds to the caspase recruitment domain (CARD) of caspase‐2 and impedes dimerization and activation of caspase‐2. Interestingly, recombinant API5 directly inhibits full length but not processed caspase‐2. Depletion of endogenous API5 leads to an increase in caspase‐2 dimerization and activation. Consistently, loss of API5 sensitizes cells to caspase‐2‐dependent apoptotic cell death. These results establish API5/AAC‐11 as a direct inhibitor of caspase‐2 and shed further light onto mechanisms driving the activation of this poorly understood caspase.

Keywords: apoptosis, apoptosis inhibitor 5, caspase‐2, cell death, pore‐forming toxins

Subject Categories: Autophagy & Cell Death

Introduction

Normal development and tissue homoeostasis are regulated by apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death (PCD) defined by unique morphological and biochemical features 1. Caspases are key executioner enzymes of apoptosis and depending on the chronology of activation, they are classified into initiator and effector caspases 2. Caspases cleave hundreds of substrates to elicit an apoptotic phenotype, and thus, the activation of caspases is tightly controlled. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) are thus far the only known endogenous inhibitors of caspases as they can directly bind to caspases and prevent their activation 3. Initiator caspases are activated by dimerization, which is accomplished by recruitment of caspase monomers to multimeric protein complexes assembled in cells in response to apoptotic stimuli 4. For instance, caspase‐8 is recruited and activated in the death‐inducing signalling complex (DISC) and caspase‐9 is recruited to the apoptosome for activation 5. Caspase‐2 is a unique member of the caspase family as it exhibits features of both initiator and effector caspases 6. More recent studies revealed other functions of this caspase: it suppresses tumours, plays a role in autophagy and regulates metabolism and ageing (for reviews see 7, 8). In response to DNA damage, caspase‐2 is recruited to a high molecular weight complex called PIDDosome which contains PIDD (p53‐induced protein with a death domain DD) and the adapter protein RAIDD (receptor‐interacting protein‐associated ICH‐1/CED‐3 homologous protein with a DD) 9. However, recent evidence suggests that caspase‐2 can be activated in a PIDDosome‐independent manner 10. We have previously shown that caspase‐2 functions as an initiator caspase during pore‐forming toxin (PFT)‐mediated apoptosis in a variety of cell types 11. In these settings, the activation of caspase‐2 is PIDDosome‐independent and critically dependent on the intracellular potassium ion concentration. Depletion of intracellular potassium ions by PFTs led to oligomerization and recruitment of caspase‐2 into a high molecular weight complex thus leading to its activation.

In our attempts to uncover the molecular determinants that drive the activation dynamics of caspase‐2 in PFT‐mediated apoptosis, we identified API5/AAC‐11/FIF (anti‐apoptosis clone 11 and fibroblast growth factor‐2 interacting factor) as a novel inhibitor of caspase‐2. API5 was originally discovered as a protein responsible for protecting cells against growth factor deprivation‐induced cell death 12. API5 can also bind to acinus, ALC1 and FGF2 regulating cell death and tumorigenesis 13, 14, 15, 16. Structurally, API5 comprises of multiple helices constituting HEAT (Huntingtin, elongation factor 3, PR65/A, TOR)‐like and ARM (Armadillo)‐like repeats that mediate protein–protein interactions 17. API5 also inhibits E2F1‐dependent apoptosis in a transcription‐independent manner 18. Recent studies revealed that API5 is highly expressed in various cancers and associated with poor prognosis especially in NSCLCs and cervical cancer; however, the molecular mechanisms behind API5‐mediated cell survival remains poorly understood 19, 20. Here, we reveal that API5 directly binds to the CARD domain of caspase‐2 and prevents its dimerization and activation. Loss of API5 thus sensitizes cells to caspase‐2‐dependent apoptotic cell death.

Results and Discussion

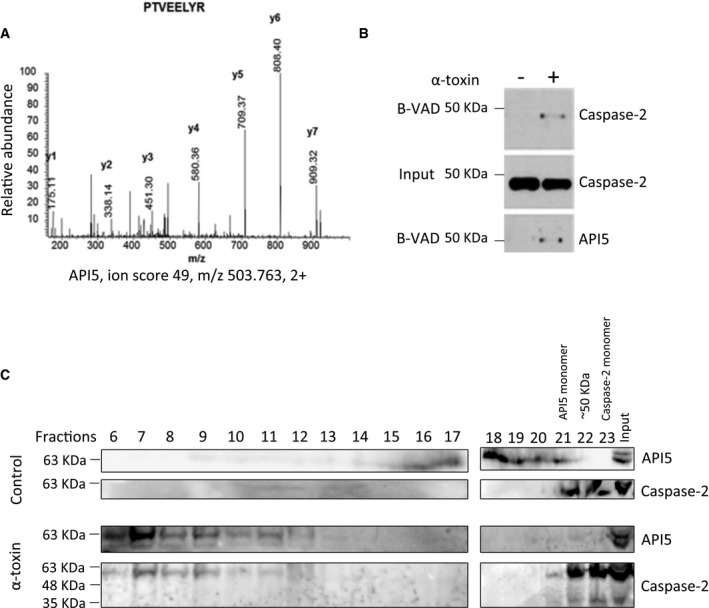

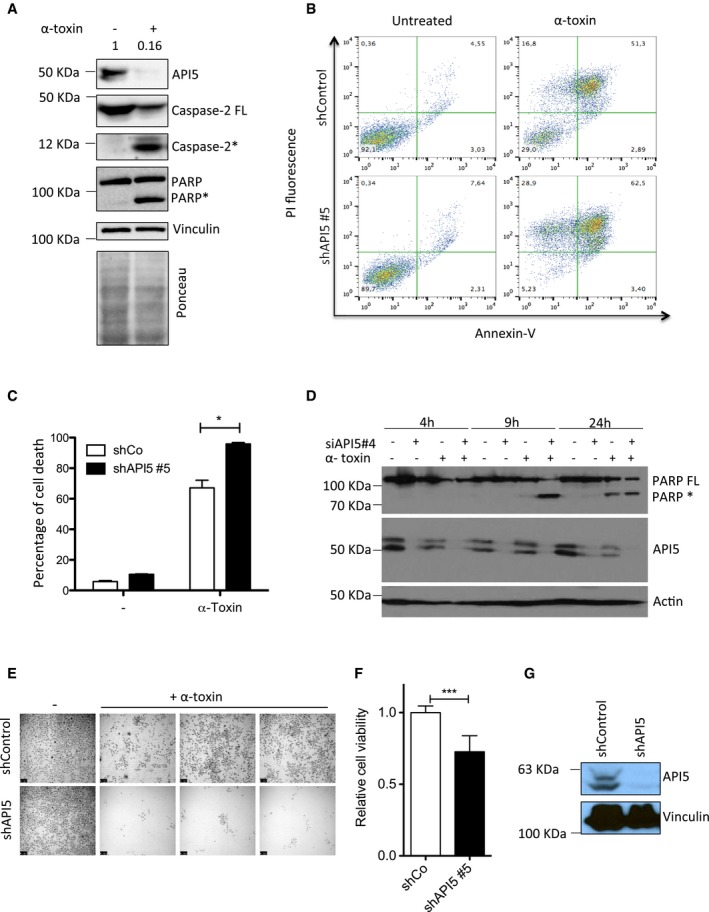

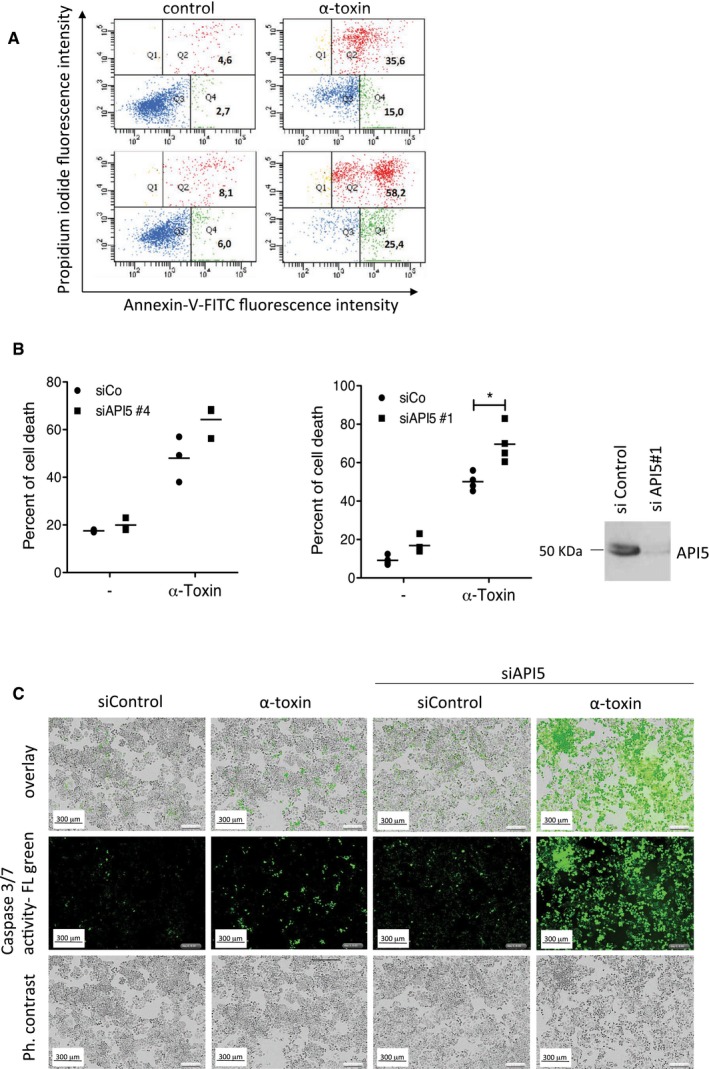

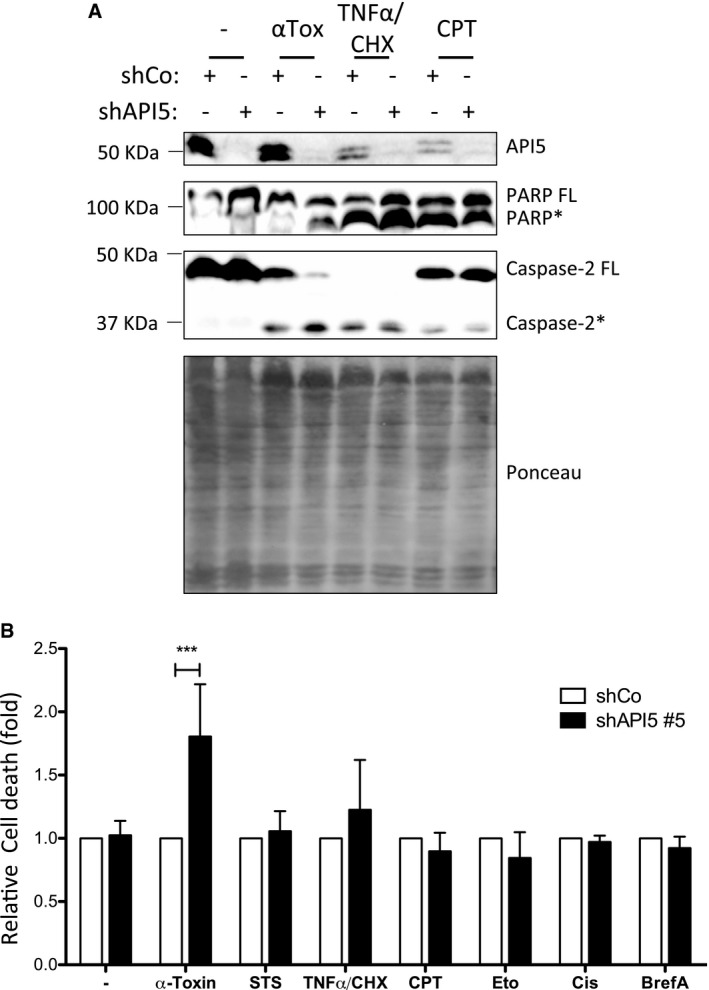

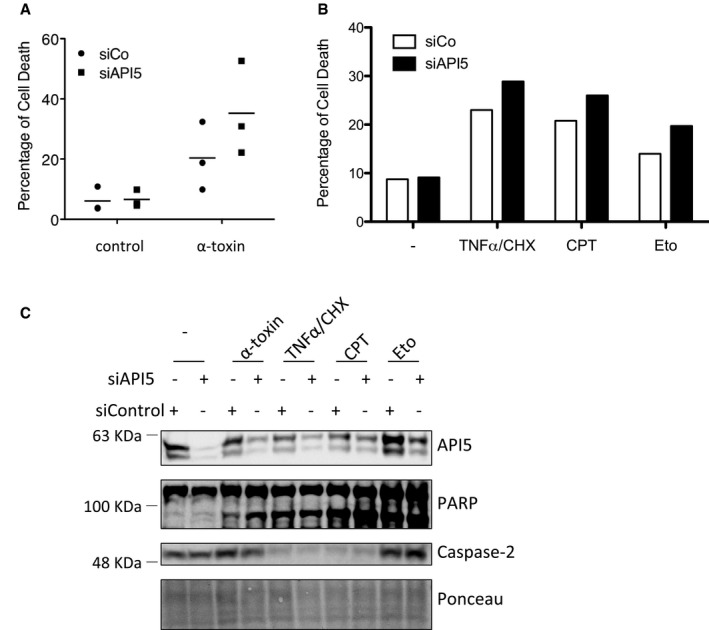

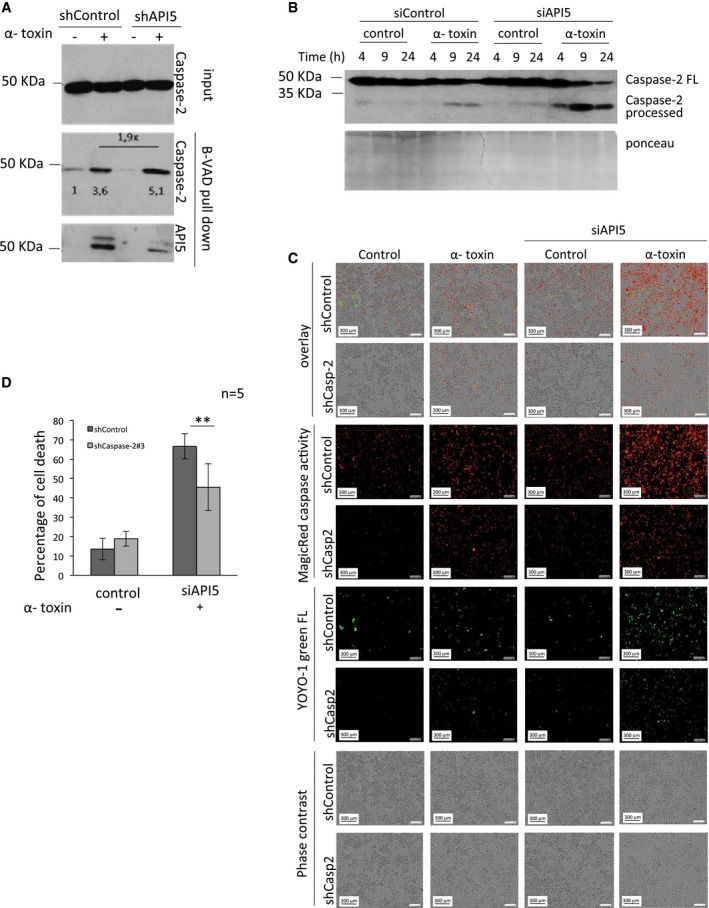

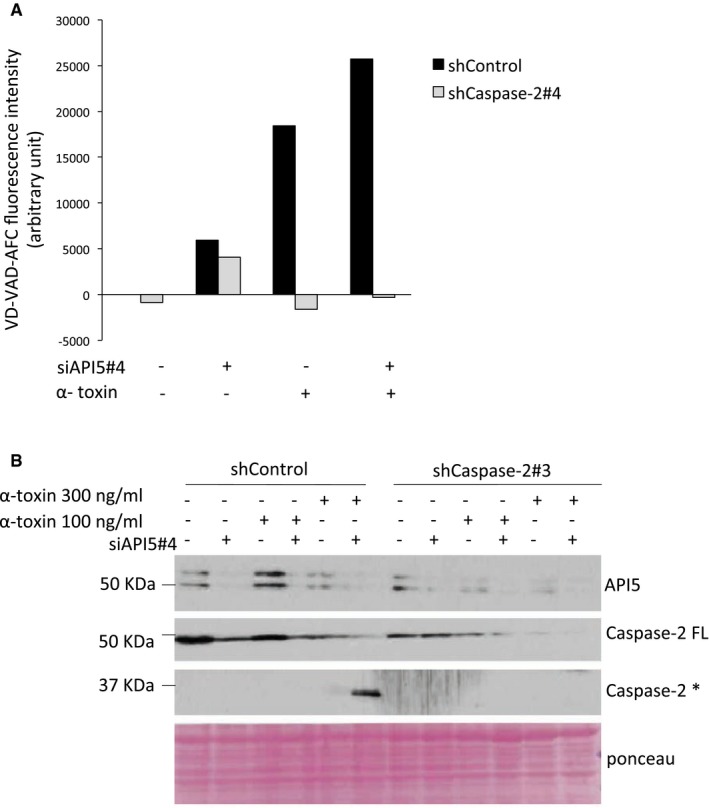

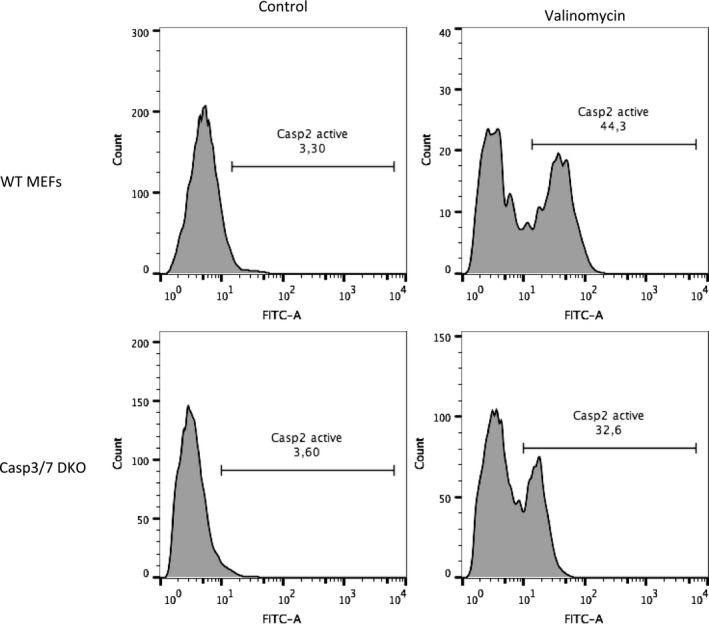

Caspase‐2 functions as an initiator caspase during PFT‐mediated apoptosis in multiple cell types 11. To identify proteins that regulate caspase‐2 activation in these settings, we have performed a mass spectrometry‐based analysis of active caspase‐2‐containing protein complexes. HeLa cells treated with biotin‐VAD‐fmk were subjected to α‐toxin treatment and proteins bound to biotin‐VAD‐fmk were precipitated by streptavidin beads. We subjected the proteins bound to the streptavidin beads to trypsin digestion and performed mass spectrometry analysis. As expected, caspase‐2 peptides were identified and among the other co‐precipitated proteins, we identified four unique peptides with six peptide spectrum matches for apoptosis inhibitor 5 (Fig 1A). We confirmed the presence of API5 in active caspase‐2‐containing complexes by immunoblots (Fig 1B). As shown before 14, 19, API5 antibodies detect a double band in HeLa cells recognizing both the 55‐ and 57‐kDa isoforms (Fig 1B). Gel filtration analysis revealed that API5 and caspase‐2 are shifting towards high molecular weight fractions in PFT‐treated cells (Fig 1C). Together, these results confirmed that API5 is probably associated directly with the activation of caspase‐2. We then explored whether API5 plays a role in the regulation of cell death mediated by PFTs. Immunoblot analysis of PFT‐treated cells revealed that API5 tends to be degraded in apoptotic cells (Fig 2A). To decipher the physiological role of API5 in regulating caspase‐2 activation, we resorted to both siRNA‐ and shRNA‐mediated loss of function approaches. As expected, stable knockdown of API5 sensitized HeLa cells to PFT‐mediated cell death (Fig 2B and C). These results are recapitulated with two different siRNAs targeting API5 (Figs 2D and EV1A and B). Consistently, enhanced PARP cleavage is detected in API5‐depleted cells as early as 9 h post‐induction (Fig 2D). As expected, enhanced caspase‐3/7 activity was detected in API5‐depleted cells treated with PFT (Fig EV1C). Long‐term clonogenicity and cell survival assays with API5‐specific shRNAs further confirmed that depletion of API5 significantly reduced the survival of PFT‐treated HeLa cells (Fig 2E–G). API5‐depleted cells were sensitized to PFT but not to TNF‐α/CHX, staurosporine, camptothecin, etoposide, cisplatin and brefeldin A (Fig 3A and B). To avoid any cell type‐specific phenotypes, we performed similar experiments in NCI‐H1650 lung carcinoma cell lines. Depletion of API5 strongly sensitized these cells to PFT‐ but not to TNF‐α/CHX‐, camptothecin‐ or etoposide‐induced cell death (Fig EV2A–C). We then tested whether API5 directly influences caspase‐2 activation in vivo. Caspase‐2 possesses a CARD domain at its N‐terminus and CARD‐mediated dimerization is required for its initial activation 21, 22. This initial activation step is followed by auto‐processing leading to a mature caspase‐2 dimer containing two P19 and P12 subunits 7. We tested whether caspase‐2 dimerization and/or activation are enhanced in response to PFTs in API5‐depleted cells by employing the “in situ active caspase trapping” approach 22, 23. As expected, experiments employing biotin‐VAD revealed that more active, dimerized caspase‐2 was detected in API5‐depleted cells after PFT treatment (Fig 4A). Caspase‐2 activity assays employing a fluorogenic substrate (VDVAD‐AFC) also confirmed increased caspase‐2 activation in API5‐depleted cells in response to PFTs (Fig EV3A). Further, we also detected enhanced caspase‐2 processing in response to PFT in API5‐depleted cells (Figs 3A, 4B and EV3B). As caspase‐2 processing can also happen downstream of effector caspase activation 24, we have reconfirmed whether caspase‐2 activation is triggered in the absence of caspase‐3/7 in response to depletion of potassium ions as with PFTs 11. To perform these experiments, we have employed valinomycin as MEFs are unresponsive to α‐toxin. As expected, caspase‐2 activity was triggered in caspase‐3/7 double knockout MEFs in response to valinomycin (Fig EV4).

Figure 1. Apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5) is identified in caspase‐2‐containing protein complexes.

- Mass spectrometry analysis of active caspase‐2 complexes. HeLa cells were pre‐incubated with biotin‐VAD‐fmk (B‐VAD, 50 μM) for 1 h and the cells were subsequently treated with 300 ng/ml of α‐toxin as mentioned in the Materials and Methods. The cells were then harvested and the active caspase‐2 complexes were precipitated by streptavidin agarose beads. The entire sample was subjected to trypsin digestion, and the proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. Shown is the MS/MS spectra of one of the API5 peptides identified.

- The presence of API5 in caspase‐2 complexes was verified by immunoblot analysis.

- Gel filtration analysis of control and PFT‐treated HeLa cell lysates. HeLa cells were treated with α‐toxin (150 ng/ml) for 4 h. Then, the cells were harvested, lysed and the crude protein extract was prepared for gel filtration analysis. The proteins were separated by size‐exclusion chromatography as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. The proteins from each collected fraction were precipitated, and the presence of proteins of interest was tested by Western blot analysis. The individual fractions are indicated.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure 2. Depletion of API5 sensitizes cells to PFT‐induced apoptosis.

- API5 is degraded during PFT‐mediated apoptosis. HeLa cells were treated with α‐toxin (300 ng/ml for 24 h) and the presence of API5, caspase‐2, and PARP was tested by immunoblots. Ponceau‐stained membrane is presented below to verify the loading (* indicates processed caspase‐2 and PARP).

- API5 depletion sensitizes HeLa cells to PFT‐mediated apoptosis. ShControl and shAPI5 HeLa cells were treated with α‐toxin (600 ng/ml for 24 h), and the percentage of cell death was analysed by FACS. The Annexin V/PI staining pattern of control and toxin‐treated cells from a representative experiment is presented.

- Quantification of experiments presented in (B) (n = 3, Mann–Whitney test, *P‐value = 0.0286), error bars represent ±SD of the mean.

- HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs (siControl or siAPI5#4) for 1 day prior to α‐toxin treatment. The cells were harvested for Western blot analysis at different time points (as indicated). FL: full length, *: processed PARP.

- HeLa cells were treated for 24 h with α‐toxin (300 ng/ml), and the dead cells were washed away. The surviving cells were allowed to replicate for 48 h to check for clonogenic survival. Shown are data from a representative experiment. Scale bar, 250 μm.

- For testing the viability of the cells, the crystal violet assay was performed on both control and shAPI5 treated with toxin and the surviving cells were quantified. The error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3, Mann–Whitney test, ***P < 0.0001).

- The efficiency of the shAPI5 was verified by Western blot and vinculin was employed as a loading control.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV1. Depletion of API5 sensitizes cells to PFT‐mediated apoptosis.

-

A, BHeLa cells were transfected with either control or API5 siRNAs for 1 day and then treated with 300 ng/ml of PFT for 24 h. The cells were harvested and the dead cells were measured by FACS analysis after Annexin V/PI staining as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Shown in (B) are data from three (n = 3; left panel) or four (n = 4, middle panel) independent experiments. The dead cells include Annexin V‐positive early apoptotic as well as Annexin V/PI double‐positive cells, indicating the late apoptotic/secondary necrotic populations as analysed by flow cytometry. The efficiency of the knockdown with siRNA#1 was monitored by immunoblots (B, right panel).

-

CMicroscopy analysis of API‐5 depleted cells upon α‐toxin treatment. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA and treated with PFT as mentioned before. The cells were treated with in situ caspase‐3/7 substrate (green) for 30 min as mentioned in the Materials and Methods. The images were acquired after 6 h post‐toxin treatment. Scale bar, 300 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure 3. Depletion of API5 sensitizes HeLa cells to PFT, but not to other inducers of apoptosis.

-

A, BShControl and shAPI5 cells were treated for 24 h with α‐toxin (150 ng/ml), staurosporine (STS, 125 nM), TNF‐α (20 ng/ml)/CHX, camptothecin (CPT, 4 μM), etoposide (ETO, 50 μM), cisplatin (Cis, 40 μM) or brefeldin A (BrefA, 5 μM). Cells were harvested and labelled with propidium iodide for cell death assay (B) or lysed for Western blot analysis (A) (* indicates processed caspase‐2 and PARP). The Ponceau staining of the entire membrane is shown below. For (B) n = 3, two‐way ANOVA with a Bonferroni test, ***P‐value < 0.001.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV2. Depletion of API5 sensitizes NCI‐H1650 cells to PFT‐mediated apoptosis.

-

A–CNCI‐H1650 cells (lung adenocarcinoma) cells were transfected with control or API5 siRNAs employing Saint‐Red reagent. After 24 h, the cells were treated with α‐toxin (150 ng/ml), TNF‐α (20 ng/ml)/CHX, camptothecin (4 μM) or etoposide (50 μM) for 24 h. Cells were harvested and labelled with propidium iodide for analysing cell death by (A, B) FACS analysis (n = 3 in A, n = 1 in B) or for (C) Western blot analysis.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure 4. Depletion of API5 enhances caspase‐2 activation and caspase‐2‐dependent cell death.

- Depletion of API5 enhances caspase‐2 dimerization and activation. ShControl and shAPI5 HeLa cells were incubated with biotin‐VAD‐fmk (B‐VAD, 50 μM) 1 h prior to α‐toxin (300 ng/ml) treatment and incubated for 18 h. The active caspase‐2 complexes were precipitated with streptavidin–agarose beads as mentioned in the Materials and Methods section. The samples were then tested for the presence of active caspase‐2 and API5 by immunoblot analysis. The relative intensity of caspase‐2 bands was measured by ImageJ software and is indicated below the bands.

- HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs, and 24 h later, they were challenged with α‐toxin at different concentrations and the processing of caspase‐2 was monitored by immunoblots. FL: full‐length caspase‐2.

- Microscopy analysis of API5‐ and caspase‐2‐depleted cells upon α‐toxin treatment. ShControl and shCaspase‐2 HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs and 24 h later, the cells were pre‐incubated with fluorescent Magic Red Caspase substrate and green fluorescent YOYO‐1 for 30 min following the manufacturers' instructions. The cells were treated with α‐toxin (300 ng/ml) for 24 h. The images were acquired at 12 h post‐treatment in the IncuCyte imaging system. Scale bar, 300 μm.

- ShControl and shCaspase‐2 HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs, and 1 day later, the cells were challenged with α‐toxin (300 ng/ml). The samples were subjected for Annexin V/PI measurements by flow cytometer as mentioned in the Materials and Methods. The error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 5), **P‐value = 0.00897 (Student's t‐test).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV3. Depletion of API5 enhances caspase‐2 activation and processing.

- Measuring caspase‐2 activity. ShControl and shCaspase‐2 HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs, and 24 h later, they were challenged with α‐toxin (300 ng/ml); 24 h post‐treatment, the samples were subjected to in vitro caspase‐2 activity measurement as indicated in the Materials and Methods and following manufacturer's instructions.

- The cells were treated as above and 24 h later were subjected to Western blot analysis. FL: full length, *: processed form.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV4. Caspase‐2 is activated in response to potassium ion depletion in a caspase‐3/7‐independent manner.

Wild‐type or caspase‐3/7 double KO MEFs were treated with valinomycin (30 μM) for 24 h. Cells were then collected and treated with FAM‐VDVAD‐FMK‐FLICA reagent. Caspase‐2 activity was measured by FACS analysis following the manufacturer's protocol (ImmunoChemistry). Shown are data from a single representative experiment.

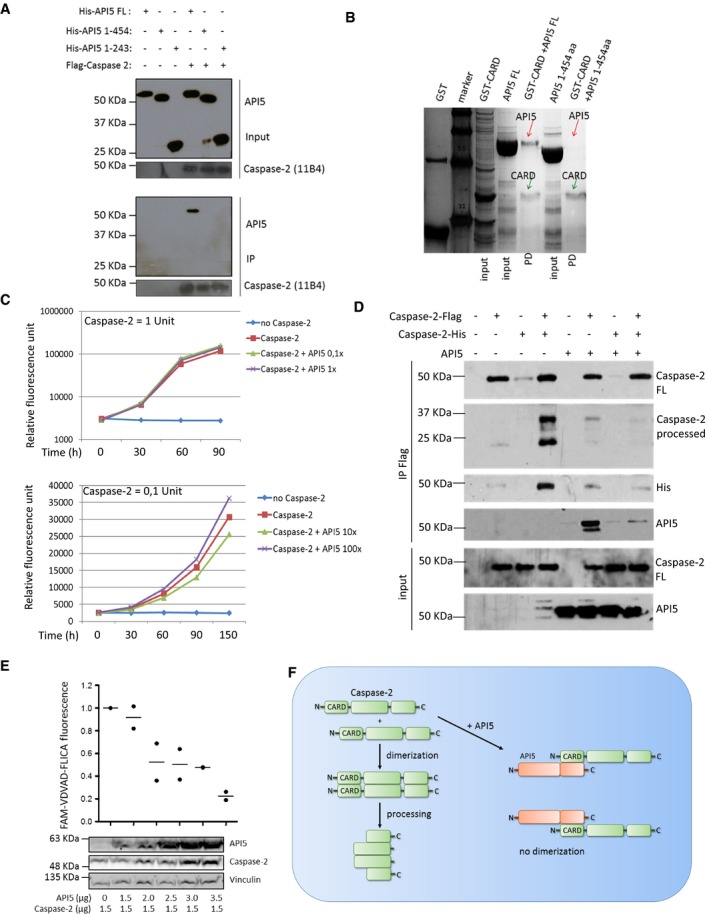

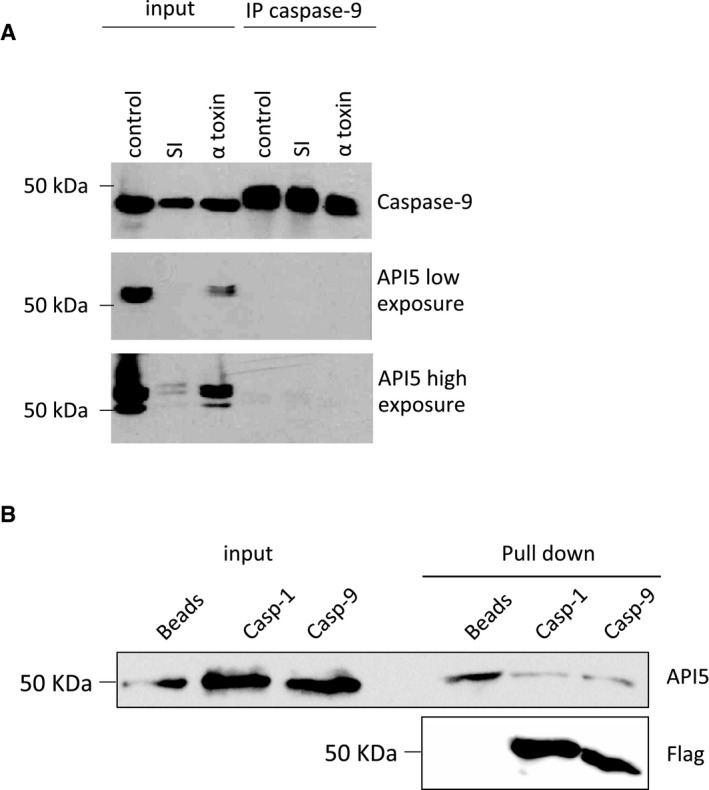

We then tested whether the sensitization to cell death observed in API5‐depleted cells is dependent on caspase‐2. Consistently, co‐knockdown of caspase‐2 reduced the sensitization to apoptosis in API5‐depleted cells suggesting a role for API5 in inhibiting caspase‐2‐mediated cell death (Fig 4C and D). In addition, we explored the potential mechanisms by which API5 can regulate caspase‐2 dimerization. As API5 possesses HEAT repeats and ARM‐like repeats, we tested whether API5 can directly interact with caspase‐2. Flag pull‐down experiments employing recombinant API5 and in vitro‐translated caspase‐2 produced from rabbit reticulocyte lysates revealed a direct interaction between API5 and caspase‐2 (Fig 5A). Interestingly, deletion of 50 amino acids at the C‐terminus of API5 (API5 1–454 = API5ΔC) abrogated this interaction (Fig 5A). As API5 directly binds to caspase‐2 and regulates caspase‐2 dimerization, we hypothesized that API5 can directly bind to the CARD domain, which is responsible for driving this dimerization event. In vitro binding experiments, employing recombinant proteins confirmed a direct interaction between the CARD domain of caspase‐2 and API5 (Fig 5B). As expected, API5ΔC failed to interact with the CARD domain of caspase‐2. As CARD domains are also present in other caspases like caspase‐9 and caspase‐1, we tested whether API5 can bind to them. Interestingly, we failed to detect any interaction between API5 and caspase‐9 or caspase‐1 (Fig EV5A and B). Consistently, loss of API5 failed to sensitize cells to caspase‐9‐dependent cell death (Fig 3B). Next, we tested whether recombinant API5 can directly inhibit the activity of fully processed recombinant caspase‐2, which is devoid of CARD domains. Incubation of increasing concentrations of API5 failed to inhibit the activity of fully processed caspase‐2 (Fig 5C). To further confirm the role of API5 in inhibiting dimerization of the CARD domains directly, we performed in vitro reconstitution experiments employing full‐length caspase‐2 purified from rabbit reticulocyte lysates. As expected, presence of API5 directly prevented the dimer formation between Flag‐tagged caspase‐2 and His‐tagged caspase‐2 (Fig 5D). To further confirm these observations, we have performed additional gain of function experiments. Consistently, overexpression of API5 inhibited the activity of co‐expressed caspase‐2 in a concentration‐dependent manner (Fig 5E). Taken together, these data suggest that API5 is a direct inhibitor of caspase‐2 and that API5 directly binds and impedes CARD‐mediated dimerization and activation (Fig 5F).

Figure 5. API5 directly interacts with the CARD domain and prevents caspase‐2 dimerization.

- API5 directly interacts with caspase‐2. In vitro‐translated Flag‐tagged caspase‐2 was incubated with recombinant API5 and its truncated versions for 2 h and caspase‐2 was pulled down with Flag‐M2 beads. The samples were eluted and subjected to Western blot analysis to check for binding between caspase‐2 and API5. 11B4 refers to the antibody clone raised against caspase‐2. The various constructs of API5 and their respective amino acid compositions are indicated above. FL: full length, aa: amino acid.

- The interaction between recombinant API5 and the CARD domain of caspase‐2 was tested by GST pull‐down experiments as indicated in the Materials and Methods section. The samples were eluted and separated via SDS–PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. The red arrow indicates the anticipated size of API5. The green arrow shows the anticipated size of caspase‐2–GST–CARD. PD: pull‐down.

- Human recombinant caspase‐2 was incubated with different concentrations of human recombinant API5 (1× = 100 ng) for 1 h at 37°C and subjected to caspase activity measurement using a fluorescent plate reader as mentioned in the Materials and Methods.

- In vitro‐translated caspase‐2‐Flag and caspase‐2‐His were co‐incubated with increasing concentrations of in vitro‐translated API5 protein for 30 min and caspase‐2‐Flag was immunoprecipitated. IP Flag: co‐immunoprecipitation, input: total sample before IP, FL: full length.

- API5 overexpression inhibits caspase‐2 activity; 293T were transected with caspase‐2 with increasing amounts of API5 for 48 h. Cells were then collected and treated with FAM‐VDVAD‐FMK‐FLICA for measuring caspase‐2 activity following manufacturer's instructions (ImmunoChemistry) (n = 2).

- Schematic view of API5‐mediated inhibition of caspase‐2 dimerization and activation. N: N‐terminus, C: C‐terminus of the protein.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV5. API5 did not interact with caspase‐9 and caspase‐1.

- HeLa cells were incubated in serum‐free EBSS (SI, starvation‐induced) media or treated with α‐toxin, and the samples were lysed and subjected to caspase‐9 immunoprecipitation (IP) (see Materials and Methods) 24 h post‐treatment. The total lysates and the immunoprecipitated‐eluted samples were analysed by Western blot.

- 293T cells were transfected with pCMV2‐Flag‐Caspase‐1 or pCMV3‐Flag‐Caspase‐9 for 48 h. The Flag‐tagged caspases were precipitated by anti‐Flag M2 Magnetic Beads. The anti‐Flag M2 Magnetic Beads were washed 5 times and then incubated overnight at 4°C with recombinant API5. After washing (3×), the beads were re‐suspended in SDS buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins are known to inhibit caspases (casp‐8/9 and casp‐3/7) directly through their BIR (Baculoviral IAP Repeat) domains and RING domains and direct inhibitors of caspase‐2 are thus far unknown 25. Caspase‐2 was cloned in 1994 and despite intense research, the molecular machinery driving the activation of this caspase remains unclear 26, 27. Though the PIDDosome serves as an activation platform during DNA damage‐mediated apoptosis, caspase‐2 can also be activated in the absence of PIDD and RAIDD 10. We have demonstrated that caspase‐2 can be recruited to a high molecular weight complex in a PIDD‐ or RAIDD‐independent manner in response to PFTs in human epithelial cells 11. Here, by employing mass spectrometry, we identified API5 as a novel inhibitor of caspase‐2. While cleavage is essential for effector caspase activation, initiator caspases depend on dimerization of caspase monomers but not on cleavage for activation 5. Initiator caspases are brought to close proximity in multimeric protein complexes leading to their activation and auto‐processing. CARD domain‐containing proteins exhibit homophilic interactions with other CARD domain‐carrying proteins leading to the formation of high order multimers in cells 28. Thus, binding of CARD domain‐containing caspases with adaptor molecules like RAIDD or APAF1 leads to an increased local concentration of the initiator caspases resulting in their dimerization and activation. Here, we present one of the first inhibitors of caspases that directly interferes with the CARD–CARD interaction both in vitro and in vivo. Our in vitro binding experiments with recombinant proteins reveal that the C‐terminus of API5 is required for interaction with the caspase‐2 CARD domain. However, it is currently unclear whether the C‐terminal fragment drives the interaction or whether the deletion of the API5 C‐terminus leads to an altered conformation of API5 that fails to interact with CARD domains. Interestingly, we could not detect any interaction with the CARD domain of caspase‐9 or caspase‐1. Thus, further biochemical and structural analyses are clearly warranted to characterize the interaction between API5 and caspase‐2. API5 has also been shown to be upregulated in several cancers and our studies raise the possibility that inhibition of caspase‐2 activation could possibly contribute to the pro‐tumorigenic role of API5 and chemoresistance. Interestingly, API5 is degraded in apoptotic cells (Figs 2A and 3A) and further studies are warranted to uncover the mechanisms driving this degradation. Further, caspase‐2 was originally identified to contribute to growth factor deprivation‐induced apoptosis, a process directly inhibited by API5 overexpression 29. Our preliminary data suggest that loss of API5 also sensitizes tumour cells to starvation‐induced cell death (G. Imre and K. Rajalingam, unpublished observations). However, it is currently unclear whether caspase‐2 is directly involved in this process. The role of caspase‐2 in mediating DNA damage‐ or ER‐stress‐mediated apoptosis remains contentious and we detect that loss of API5 primarily sensitizes cells to PFT but not to other inducers of apoptosis (Figs 3 and EV2). API5 has also been shown to undergo phosphorylation and it would be interesting to explore whether post‐translational modifications determine the binding of API5 to caspase‐2 in cells 30. Taken together, our study reveals a novel mechanism (direct disruption of CARD‐mediated dimerization) regulating initiator caspase activation and identifies one of the first direct inhibitors of caspase‐2. The study sheds further light on the mechanisms driving the activation of caspase‐2, a poorly defined member of the caspase family.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and apoptosis induction

HeLa cells were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium and A549, NCI‐H1650, caspase‐2−/− and caspase‐3/7 DKO MEFs were cultured in DMEM (both Gibco BRL), both supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco BRL), and 0.2% penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Gibco BRL) and 2 mM l‐glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cell death experiments were performed with purified α‐toxin (α‐haemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus) (Sigma) for various time points. Staurosporine (Cell Signaling), cisplatin (Uniklinik Mainz), etoposide (Sigma), camptothecin (Selleckchem), TNF‐α (R&D Systems), cycloheximide (Sigma), brefeldin A (Selleckchem), valinomycin (Sigma).

shRNA‐mediated RNA interference by lentiviral particles

In order to achieve a stable knockdown, HeLa cells were seeded in 96‐well plate format at 40,000 cells/100 μl medium. The next day, the medium was changed to polybrene (hexadimethrine bromide, final concentration 8 μg/ml)‐containing medium and the cells were infected with shRNA‐carrying lentiviral particles (Sigma) at an MOI of 5. The medium was changed 24 h later. At 48 h post‐infection, the cells were trypsinized and re‐suspended in puromycin‐containing medium and seeded into 12‐well plates. To avoid clonal‐specific effects, a pool of infected cells was used for the subsequent experiments after validating the knockdown of the respective genes by Western blot analysis. The following sequences were employed for accomplishing knockdown:

caspase‐2 #3 (TRCN0000003507): 5′‐CCGGGTTGAGCTGTGAC TACGACTTCTCGAGAAGTCGTAGTCACAGCTCAACTTTTT‐3′

API5 #5 (TRCN0000294026): 5′‐CCGGGGAGAAGAGTAATGGT CAATCCTCGAGGATTGACCATTACTCTTCTCCTTTTTG‐3′

ShControl (SHC002V): non‐target shRNA control transduction particles.

SiRNA transfection

Cells were seeded into 12‐well plates to obtain 50–60% confluency the next day. Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) transfection reagent was used to achieve efficient siRNA transfection (final DNA concentration: 60 nM). The next day, the medium was changed and cells were treated with α‐toxin. Approximately a day later, the transfected samples were subjected to various treatments (like apoptosis induction) as specified in the figure legends. The following siRNAs provided efficient knockdowns: siAPI5#1 (SI02225580, QIAGEN), siAPI5#4 (Hs02_00341902, Sigma).

Cell death assays

After the respective treatments, the cells (0.5 × 106 cells) were collected by trypsinization. Samples were washed once with PBS and then resuspended in 100 μl of 1× annexin binding buffer provided by the manufacturer (ENZO), and 5 μl of Annexin V‐FITC stock solution and 1 μg/ml (final concentration) propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma) were added to the cells and incubated for 15 min. After incubation, the stained samples were measured by flow cytometry. The cell debris was excluded from analysis. For the flow cytometry analysis, the following channels were used: FITC‐FL1 channel (488‐nm blue laser/530‐nm band‐pass filter), PI‐FL2 channel (488‐nm blue laser/585‐nm band‐pass filter; BD FACSCanto I and II, Becton Dickinson). For long‐term clonogenicity assays, 1 × 105 Shcontrol and shAPI5 knockdown cells were seeded into 12‐well plates and treated with 300 ng/ml of α‐toxin for 24 h. The dead cells were washed away and the surviving cells were allowed to replicate for 2 days to test their clonogenic capacity. The cells were labelled using crystal violet solution, and pictures of the clones were taken from various fields. For testing cell viability, 1 × 104 control and API5 knockdown cells were seeded into 96‐well plates and treated with 300 ng/ml α‐toxin for 24 h. The dead cells were washed away, and the surviving cells were labelled with crystal violet solution. The crystal violet was then eluted using 33% acetic acid, and the absorbance at 590 nm was measured. The relative cell viability was calculated by setting the cell viability of the untreated cells as 1.

Biotin‐VAD pull‐down of activated caspases

HeLa cells were seeded into six‐well plates and were grown until 80–90% confluency. They were treated with 50 μM biotin‐VAD (MP Biomedicals, Enzyme System Products) for 1 h and then 300 ng/ml of α‐toxin was added to the cells. The cells were incubated for various time points and then collected by scraping. The collected cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 500 μl KPM buffer [50 mM KCl, 50 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 1.92 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)]. The cells were lysed by repeated freezing and thawing (3×) and centrifuged for 10 min (15,000 g, 4°C); 50 μl of the supernatant was collected as loading control. The rest of the sample (450 ml) was incubated with 30 μl of streptavidin agarose beads (Invitrogen) at 4°C on a vertical rotator overnight. The next day, samples were centrifuged (500 g for 3 min at 4°C) and the supernatant was thoroughly discarded. The beads were resuspended in 500 μl of KPM buffer. This step was repeated three times. Finally, the beads were resuspended in 60 μl of 5× Laemmli buffer with 5% β‐mercaptoethanol, were boiled and subjected to SDS–PAGE for subsequent immunoblot or mass spectrometric analysis. The mass spectrometry analysis was essentially performed as described earlier 11.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed directly in 5× Laemmli (with 5% β‐mercaptoethanol) buffer and the proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (90 min, 860 mA, RT), and the presence of proteins was monitored by immunoblot analysis following standard procedures. The following primary antibodies were employed: anti‐caspase‐2 (clone 11B4, Alexis), anti‐API5, anti‐caspase‐9, anti‐PARP, anti‐His (Cell Signaling Technologies) and anti‐actin (Sigma).

Fluorescence time‐lapse microscopy

HeLa cells were plated into 12‐well plates. Immediately after treatment, the cells were stained with either Caspase‐3/7 reagent (Essen Bioscience), alternatively with YOYO‐1 (Life Technologies) and Magic Red Caspase‐3/7 Detection Kit (Immunochemistry Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. The plates were incubated in the IncuCyte Zoom automated microscopy system (Essen BioScience), which enabled us to conduct the measurements inside a cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) in order to ensure stable conditions for long‐term measurements. Images were taken with a digital camera attached to the microscope at various time points (green channel: Caspase‐3/7 and YOYO‐1; red channel: Magic Red Caspase‐3/7; phase contrast channel) with 10× objective.

In vitro translation

In vitro translation assays were performed using the TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate (Promega) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of pCDNA3‐caspase‐2‐Flag(C) (Addgene #11811, kind gift from Prof. Guy Salvesen), pET‐53‐DEST‐caspase‐2‐His(N) or pCDNA3‐API5‐T7 (kind gift from Dr. Jean Luc Poyet) was mixed with T7 polymerase, rabbit reticulocyte lysate (25 μl), amino acid cocktail, RNase inhibitor and buffer provided by the manufacturer. The samples were incubated 30°C for 90 min and subsequently frozen at −80°C.

In vitro pull‐down experiments

The DNA encoding the CARD domain (amino acid 15–104) of human caspase‐2 was amplified with PCR and cloned into pGEX4T vector (GE Healthcare) using BamHI and XhoI restriction sites generating a N‐terminal GST‐fusion construct. The recombinant protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21_pLysS (Novagen). The cells were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin. Protein expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropylβ‐D‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the cells reached an optical density at 600 nm of about 0.5 and cell growth continued for 20 h at 18°C.

The pellet was resuspended in buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted by sonication on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto GST‐binding resin (Novagen) using an open column which had previously been equilibrated with buffer A (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) and subsequently was washed with buffer A. The protein was eluted with buffer A containing 20 mM reduced l‐glutathione. Product homogeneity of the purified protein was determined by SDS–PAGE under denaturing conditions using 12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gels. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

API5 His‐tagged protein was purified by a Ni2+‐chelated NTA Agarose (Qiagen) using an open column. GST–CARD protein and GST protein itself were purified by GST resin (Novagen) using an open column. The elution buffer of the purified proteins (API5, CARD and GST) was changed to buffer B (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.0025% Tween‐20) using an Amicon Ultra‐15 ultrafiltration device. The proteins were concentrated to 1 mg/ml. The GST–CARD tag protein and GST protein were immobilized on GST resin by incubating with GST resin which had previously been equilibrated with buffer B for 90 min at 4°C. After incubation, these columns were washed three times with buffer B using open columns. The API5 protein was loaded onto GST–CARD tag protein‐bound GST resin and GST protein‐bound GST resin, and washed three times with buffer B. The bound proteins were eluted with buffer B containing 20 mM reduced l‐glutathione. The eluted proteins were visualized using Coomassie blue staining or Western blot analysis.

The in vitro‐translated samples were mixed with recombinant API5 and re‐suspended in 300 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X‐100). First, 30 μl of the lysate was taken as loading control. Subsequently, 20 μl of equilibrated anti‐Flag M2 Magnetic Beads (Sigma) were pipetted into tubes containing 270 μl of lysate. The samples were incubated overnight at 4°C on a vertical rotator. Next day, the samples were placed in a magnetic separator and washed three times with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4). The washed anti‐Flag M2 Magnetic Beads were resuspended in 5× Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 3 min. Finally, the eluates were collected into a separate tube and stored at −20°C until analysed by SDS–PAGE and subsequent Western blotting. For testing the interaction between caspase‐1/9 and API5, 293T cells were transfected with Flag‐tagged caspases (caspase‐9 and caspase‐1 obtained from Sinobiological). The caspases thus produced were precipitated by Flag beads, and the interaction with API5 is tested with recombinant API5 proteins as described above.

Caspase‐9 immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells were harvested at 80% confluency (two wells of a 6‐well plate/sample) and re‐suspended in 500 μl RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X‐100 with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1 mM DTT). The samples were lysed by repeated freeze–thaw cycles (3) and centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 g and 4°C. The supernatant was collected and 50 μl was taken as input. The rest of the samples was mixed with 4.5 μl of caspase‐9 antibody (Cell Signalling) and incubated overnight at 4°C in a vertical rotator. The next day, 20–30 μl of agarose A and G beads (Roche) were mixed with the samples and incubated at 4°C for 2 h on a vertical rotator. The beads were washed three times in RIPA buffer and re‐suspended in 5× Laemmli sample buffer (with 5% β‐mercaptoethanol).

Caspase‐2 activity assay

Depending on the experiment, either 1 × 106 cells or purified recombinant proteins (human recombinant caspase‐2 (ENZO) with human recombinant API5) were resuspended in 50 μl ice‐cold lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 10 min. Next, 50 μl 2× reaction buffer (with freshly added DTT, 1 mM) was pipetted, and finally, 5 μl of caspase‐2 fluorometric caspase substrate (VDVAD‐AFC, final concentration 50 μM) was mixed with the sample (Caspase‐2 Fluorometric assay kit, ENZO). The mixtures were incubated in a flat‐bottom 96‐well plate at 37°C for various time points and the fluorescence intensity increase was detected using a Fluorometric Plate Reader (Victor X, Perkin Elmer).

Size‐exclusion chromatography from endogenous samples

HeLa cells (10 × 75 cm2 flasks at 80% confluency) were treated with α‐toxin and harvested by scraping at 4 h post‐treatment. The control and treated samples were resuspended in hypotonic buffer and lysed by repeated freeze–thaw cycles (3×). Next, the lysates were centrifuged and the supernatant was collected in a separate tube. The samples were kept at 4°C and were subjected to size‐exclusion chromatography (column: sephacryl HR500 (GE)). The entire protocol was described previously 11.

Statistical analysis

Student's t‐test or Mann–Whitney test was performed for statistical significance of the results (*P = 0.05, **P = 0.01, ***P = 0.005). The sample size (number of experiments) has been indicated in the figure as n.

Author contributions

GI and JB conceived and performed most of the experiments, analysed and interpreted data and prepared figures. JH, SK and VD contributed to gel filtration studies, data analysis and interpretation. IMM performed protein–protein interaction studies. BIL contributed valuable materials and interaction studies with GST–CARD and API5. BT contributed to mass spectrometric analysis. KR conceived and designed the project, analysed and interpreted data, co‐ordinated the study and wrote the paper with inputs from all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Essen bioscience for providing us the Incucyte live cell imaging system to perform a set of experiments and Aleksandra Dimitrijevic for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Poyet and Prof. Guy Salvesen for sharing API5 and caspase‐2 plasmids and Dr. Daniela Hoeller for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by DFG RA1739/3‐1 to KR from the DFG. KR is a Heisenberg professor of the DFG, a PLUS3 fellow of the Boehringer Ingelheim Stiftung and a GFK fellow. VD acknowledges support from CEF‐MC.

EMBO Reports (2017) 18: 733–744

References

- 1. Meier P, Vousden KH (2007) Lucifer's labyrinth–ten years of path finding in cell death. Mol Cell 28: 746–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y (1998) Caspases – enemies within. Science 281: 1312–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gyrd‐Hansen M, Meier P (2010) IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF‐kappaB, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salvesen GS, Dixit VM (1999) Caspase activation: the induced‐proximity model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 10964–10967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boatright KM, Salvesen GS (2003) Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krumschnabel G, Manzl C, Villunger A (2009) Caspase‐2: killer, savior and safeguard–emerging versatile roles for an ill‐defined caspase. Oncogene 28: 3093–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumar S (2009) Caspase 2 in apoptosis, the DNA damage response and tumour suppression: enigma no more?. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Dawar S, Kumar S (2015) Old, new and emerging functions of caspases. Cell Death Differ 22: 526–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tinel A, Tschopp J (2004) The PIDDosome, a protein complex implicated in activation of caspase‐2 in response to genotoxic stress. Science 304: 843–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Manzl C, Krumschnabel G, Bock F, Sohm B, Labi V, Baumgartner F, Logette E, Tschopp J, Villunger A (2009) Caspase‐2 activation in the absence of PIDDosome formation. J Cell Biol 185: 291–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imre G, Heering J, Takeda AN, Husmann M, Thiede B, zu Heringdorf DM, Green DR, van der Goot FG, Sinha B, Dotsch V et al (2012) Caspase‐2 is an initiator caspase responsible for pore‐forming toxin‐mediated apoptosis. EMBO J 31: 2615–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tewari M, Yu M, Ross B, Dean C, Giordano A, Rubin R (1997) AAC‐11, a novel cDNA that inhibits apoptosis after growth factor withdrawal. Cancer Res 57: 4063–4069 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rigou P, Piddubnyak V, Faye A, Rain JC, Michel L, Calvo F, Poyet JL (2009) The antiapoptotic protein AAC‐11 interacts with and regulates Acinus‐mediated DNA fragmentation. EMBO J 28: 1576–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van den Berghe L, Laurell H, Huez I, Zanibellato C, Prats H, Bugler B (2000) FIF [fibroblast growth factor‐2 (FGF‐2)‐interacting‐factor], a nuclear putatively antiapoptotic factor, interacts specifically with FGF‐2. Mol Endocrinol 14: 1709–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noh KH, Kim SH, Kim JH, Song KH, Lee YH, Kang TH, Han HD, Sood AK, Ng J, Kim K et al (2014) API5 confers tumoral immune escape through FGF2‐dependent cell survival pathway. Cancer Res 74: 3556–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahel D, Horejsi Z, Wiechens N, Polo SE, Garcia‐Wilson E, Ahel I, Flynn H, Skehel M, West SC, Jackson SP et al (2009) Poly(ADP‐ribose)‐dependent regulation of DNA repair by the chromatin remodeling enzyme ALC1. Science 325: 1240–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han BG, Kim KH, Lee SJ, Jeong KC, Cho JW, Noh KH, Kim TW, Kim SJ, Yoon HJ, Suh SW et al (2012) Helical repeat structure of apoptosis inhibitor 5 reveals protein‐protein interaction modules. J Biol Chem 287: 10727–10737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris EJ, Michaud WA, Ji JY, Moon NS, Rocco JW, Dyson NJ (2006) Functional identification of Api5 as a suppressor of E2F‐dependent apoptosis in vivo . PLoS Genet 2: e196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho H, Chung JY, Song KH, Noh KH, Kim BW, Chung EJ, Ylaya K, Kim JH, Kim TW, Hewitt SM et al (2014) Apoptosis inhibitor‐5 overexpression is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients with cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 14: 545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sasaki H, Moriyama S, Yukiue H, Kobayashi Y, Nakashima Y, Kaji M, Fukai I, Kiriyama M, Yamakawa Y, Fujii Y (2001) Expression of the antiapoptosis gene, AAC‐11, as a prognosis marker in non‐small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 34: 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baliga BC, Read SH, Kumar S (2004) The biochemical mechanism of caspase‐2 activation. Cell Death Differ 11: 1234–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bouchier‐Hayes L, Oberst A, McStay GP, Connell S, Tait SW, Dillon CP, Flanagan JM, Beere HM, Green DR (2009) Characterization of cytoplasmic caspase‐2 activation by induced proximity. Mol Cell 35: 830–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tu S, McStay GP, Boucher LM, Mak T, Beere HM, Green DR (2006) In situ trapping of activated initiator caspases reveals a role for caspase‐2 in heat shock‐induced apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 8: 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paroni G, Henderson C, Schneider C, Brancolini C (2001) Caspase‐2‐induced apoptosis is dependent on caspase‐9, but its processing during UV‐ or tumor necrosis factor‐dependent cell death requires caspase‐3. J Biol Chem 276: 21907–21915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD (2008) IAPs: what's in a name? Mol Cell 30: 123–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA (1994) Induction of apoptosis by the mouse Nedd2 gene, which encodes a protein similar to the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell death gene ced‐3 and the mammalian IL‐1 beta‐converting enzyme. Genes Dev 8: 1613–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krumschnabel G, Sohm B, Bock F, Manzl C, Villunger A (2009) The enigma of caspase‐2: the laymen's view. Cell Death Differ 16: 195–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hofmann K, Bucher P, Tschopp J (1997) The CARD domain: a new apoptotic signalling motif. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 155–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haviv R, Lindenboim L, Yuan J, Stein R (1998) Need for caspase‐2 in apoptosis of growth‐factor‐deprived PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res 52: 491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren K, Zhang W, Shi Y, Gong J (2010) Pim‐2 activates API‐5 to inhibit the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through NF‐kappaB pathway. Pathol Oncol Res 16: 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5