Abstract

The role of thyroid hormones (THs) in the central regulation of energy balance is increasingly appreciated. Mice lacking the type 3 deiodinase (DIO3), which inactivates TH, have decreased circulating TH levels relative to control mice as a result of defects in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. However, we have shown that the TH status of the adult Dio3−/− brain is opposite that of the serum, exhibiting enhanced levels of TH action. Because the brain, particularly the hypothalamus, harbors important circuitries that regulate metabolism, we aimed to examine the energy balance phenotype of Dio3−/− mice and determine whether it is associated with hypothalamic abnormalities. Here we show that Dio3−/− mice of both sexes exhibit decreased adiposity, reduced brown and white adipocyte size, and enhanced fat loss in response to triiodothyronine (T3) treatment. They also exhibit increased TH action in the hypothalamus, with abnormal expression and T3 sensitivity of genes integral to the leptin-melanocortin system, including Agrp, Npy, Pomc, and Mc4r. The normal to elevated serum levels of leptin, and elevated and repressed expression of Agrp and Pomc, respectively, suggest a profile of leptin resistance. Interestingly, Dio3−/− mice also display elevated locomotor activity and increased energy expenditure. This occurs in association with expanded nighttime activity periods, suggesting a disrupted circadian rhythm. We conclude that DIO3-mediated regulation of TH action in the central nervous system influences multiple critical determinants of energy balance. Those influences may partially compensate each other, with the result likely contributing to the decreased adiposity observed in Dio3−/− mice.

The thyroid gland produces 2 main thyroid hormones (THs): the most abundant, thyroxine (T4), and the active hormone triiodothyronine (T3). TH has been known to regulate basal metabolic rate for more than a century (1–3). T3 action is mediated by its binding to nuclear T3 receptors, which act as transcription factors that regulate the expression of target metabolic genes (4). Thus, TH regulates mitochondrial activity (5) and influences the expression of nuclear-encoded respiratory genes (6), markedly enhancing mitochondrial DNA transcription (7). T3 also regulates the expression of the uncoupling proteins (UCPs), which dissipate heat by uncoupling proton electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (8). Given these molecular actions, changes in TH status are associated with changes in body weight. Thus, hypothyroidism in humans is associated with decreased metabolic rate and weight gain, which is proportional to the severity of the hypothyroidism (9). Serum levels of thyrotropin are also positively correlated with body weight (9–11).

Many of the metabolic effects of TH can be attributed to their direct actions on metabolically relevant peripheral tissues (12, 13). Thus, THs exert a wide range of effects on hepatic physiology such as lipid, cholesterol, and glucose metabolism (14–18). Additional major metabolic targets of TH signaling are the skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue (BAT). In the former, TH can regulate muscle glucose uptake, the β-oxidation of fatty acids, and tissue repair (14, 19, 20). In the latter, THs are critical for adequate Ucp1 expression and thermogenic function (21, 22).

In contrast to these well-established peripheral actions of THs, there is limited information regarding the role of THs in the regulation of energy balance by actions in the central nervous system (CNS). Recent evidence suggests that THs act within the brain to modulate food intake and peripheral energy expenditure (EE) (23–25). One key determinant of TH action in the brain is type 3 deiodinase (DIO3), which catalyzes, by inner ring deiodination, the conversion of both T4 and T3 to inactive metabolites (26). DIO3 exhibits a marked developmental pattern of expression (27–29). In rodents and humans, its expression is high in most tissues during fetal life, but in adulthood, only the CNS maintains high levels of expression (30). Thus, mice lacking DIO3 experience excessive exposure to THs during development, leading to functional deficits in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid hormone axis (31). As a result, adult Dio3−/− mice are hypothyroid.

Despite the subnormal circulating levels of TH, and because of the lack of TH clearance in the brain, we have shown that adult Dio3−/− mice manifest a hyperthyroid state in the CNS that is exacerbated with age (30, 32). We hypothesized that the enhanced levels of TH signaling in the brain of Dio3−/− mice during development or in the adult may be of functional consequence to hypothalamic circuitries that regulate energy balance and to adiposity. This includes the leptin-melanocortin system, by which adipocyte-secreted leptin represses and activates, respectively, agouti-related peptide (AGRP) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (33, 34). Neurons in the paraventricular nucleus targeted by AGRP and POMC-derived melanocortin (i.e., melanocyte-stimulating hormone) will then modulate, as appropriate, food intake and EE in peripheral tissues (33, 34).

Here we show that, in association with elevated TH action in the hypothalamus, Dio3−/− mice exhibit decreased adiposity and reduced adipocyte size, but also an abnormal set point and regulation profile of the leptin–-melanocortin system that is suggestive of leptin resistance and susceptibility to obesity. These mice also show elevated levels of physical activity in abnormal circadian rhythms, an alteration that may prevail in causing the observed phenotype of low fat mass. These observations provide insights into the central regulation of energy balance by TH and underscore a role for DIO3 in the control of those mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

Experimental Dio3+/+ and Dio3−/− mice used in the present studies were generated and genotyped as previously described (30). They were littermates produced by heterozygous parents. The father of the experimental mice had a C57Bl/6j background, and the mother was of a 129/Svj background. Thus, the genetic background of the animals used was mixed but identical, a 50:50 ratio of each of that of the parents. Both males and females were used, and the mice studied belonged to litters that were 7 to 9 mice in size. Animals were kept under a 12-hour light cycle and fed ad libitum. In 1 experiment, mice were treated for 4 weeks with 1 of 2 doses of T3 in their drinking water (0.1 µg/mL or 0.25 µg/mL).

Some Dio3+/− mice were crossed with mice carrying 1 copy of the FINDT3B or the FINDT3A transgenes, which were designed to express the β-galactosidase reporter gene under the control of T3 (32, 35). Experimental mice used for β -galactosidase staining experiments were of a C57Bl/6 and 129/Sv mixed genetic background that has been maintained by littermate breeding for more than 12 generations. These experimental mice were also littermates of Dio3+/− parents, 1 of which was hemizygous for the FINDT3 transgene. All animals were euthanized by asphyxiation with CO2. Blood was taken from the inferior vena cava, and serum was obtained by centrifugation and stored at −70°C until later use. Tissues collected were frozen on dry ice immediately after harvesting and stored at −70°C until further use. All animal studies and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Maine Medical Center Research Institute.

Serum determinations

Serum total T4 and T3 concentrations were determined using the total T4 and T3 Coat-a-Count RIA kits from Diagnostics Products (Los Angeles, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum leptin was determined using the Quantikine ELISA Kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of white and brown fat tissues

White and brown adipose tissues (WAT and BAT, respectively) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were visualized by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. White adipocyte size was determined using ImajeJ (open source image program for scientific images; http://imagej.net/ImageJ) using 4 sections from each of 4 animals per group. Nuclear staining in brown fat tissue was quantified as previously described in 7 consecutive sections spanning the areas depicted from 3 different mice (21 sections per group in total) (32).

β-galactosidase staining

Mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. The whole brain was collected and placed in a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer for 4 hours. Coronal brain sections (200–400 µm thick) were then made using a vibratome. Female brains were placed in a 15% sucrose solution overnight at 4°C after fixation, embedded in cold optimal cutting temperature compound, frozen at –70°C, and then sections were made with a cryostat. Sections were submerged in β-galactosidase staining solution for a time that varied between 1 and 4 hours. The staining solution contained saline, 2 mM of MgCl2, 0.02% Nonidet P-40 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 5 mM of potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM of potassium ferrocyanide, and 1 mg/mL of X-galactosidase (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-d-galactopyranoside). After staining, brain sections were washed with saline, dried, and mounted on slides for analysis (32).

RNA preparation and real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from the mouse hypothalamus area and adipose tissues using the RNeasy kit from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). Lipid metabolism genes in adipose tissues and hypothalamic Npy, Agrp, and Pomc expressions were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction using standard procedures. A 7300 system and a Sybr Green master mix from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) were used. One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using standard conditions, and the resulting complementary DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using a 60°C annealing temperature for 1 minute. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 1 (95.9KB, docx) .

Body composition and metabolic determinations

Fat and lean mass were measured in isoflurane-anesthetized mice using a Lunar PIXImus II DEXA Densitometer (Fitchburg, WI). For metabolic determinations, we used metabolic cages (Promethion Metabolic Monitoring Cage System, Las Vegas, NV). A standard 12-hour light/dark (L/D) cycle was maintained throughout the calorimetry studies. Prior to data collection, all animals were acclimated to running wheels for 2 days. The calorimetry system consists of 16 metabolic cages (identical to home cages with bedding), each equipped with water bottles and food hoppers connected to load cells for food and water intake monitoring. All animals had ad libitum access to standard rodent food and water throughout the study. All cages contained running wheels 4.5 ″inches (11.5 cm) in diameter (Mini-Mitter, Bend, OR) that were wired to record revolutions/s continuously using a magnetic reed switch.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between groups was determined by the 2-tailed Student t test (2 groups) or Tukey's multiple comparison test in 1-way analysis of variance (multigroups) using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Regression analysis was performed using JMP 11.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Significance was established at P ≤ 0.05 (2 tailed). Correlations are reported as Pearson r values (36, 37).

Results

Dio3−/− mice show reduced adiposity

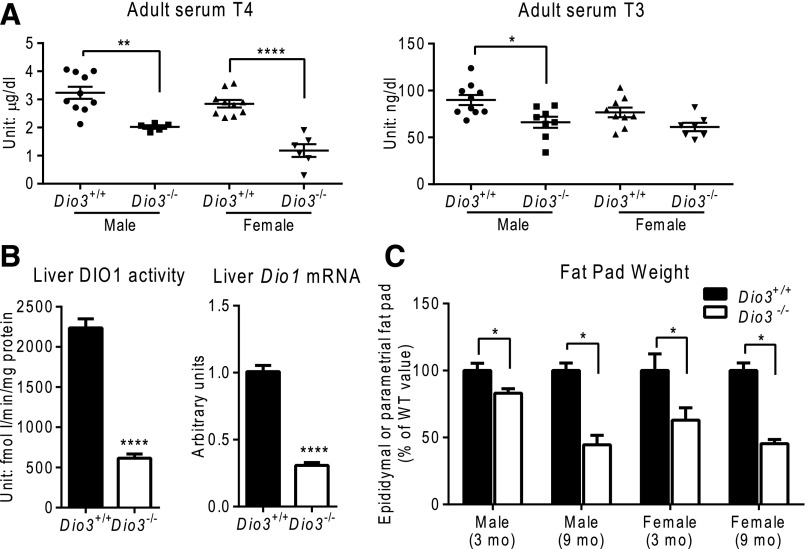

Consistent with our previous work (30), Dio3−/− mice in the current study demonstrated diminished circulating levels of T4 and T3 in both sexes [Fig. 1(A)]. This peripheral hypothyroid state is illustrated by the reduced hepatic messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and enzymatic activity of the T3-dependent gene Dio1 [Fig. 1(B)]. Dio3−/− mice also exhibited a marked decrease in adiposity when compared with Dio3+/+ littermates. The relative weights of epididymal or parametrial fat pads in young and especially old Dio3−/− mice of either sex were significantly reduced, when compared with those in Dio3+/+ mice of corresponding age and sex [Fig. 1(C)].

Figure 1.

Leanness despite hypothyroidism in Dio3−/− mice. (A) Serum T4 and T3 levels of adult mice. (B) Hepatic DIO1 activity and Dio1 gene expression in adult mice. (C) Relative epididymal and parametrial fat pad weights (corrected by body weight and expressed as a % of values in Dio3+/+ mice) of 3- and 9-month-old mice of both sexes. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by the Student t test.

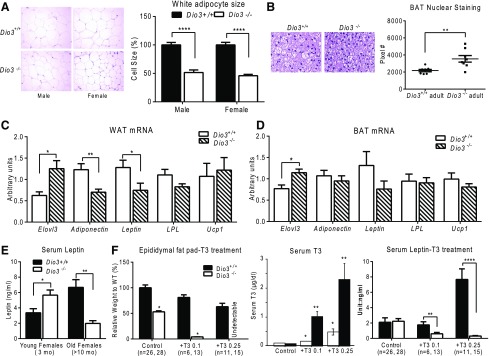

Decreased cell size and altered gene expression in WAT and BAT of Dio3−/− mice

Changes at the histological and molecular level were identified in the WAT and BAT of Dio3−/− mice. Adipocyte size was significantly reduced in the WAT of Dio3−/− mice, as determined by measurements on H&E-stained tissue [Fig. 2(A)]. Likewise, BAT adipocytes in Dio3−/− mice were also smaller than those from Dio3 +/+ mice, as indicated by increased nuclear staining per section area in comparable tissue sections [Fig. 2(B)].

Figure 2.

Reduced adipocyte size and changes in adipose tissue gene expression in Dio3−/− mice. (A) H&E staining of WAT (left) and white adipocyte size (right). (B) H&E staining of BAT (left) and quantification of nuclear staining (right). (C) Gene expression in WAT of 3-month-old male mice. (D) Gene expression in BAT of 3-month-old male mice. (E) Serum leptin in 3- and 9-month-old female mice. (F) Relative weight of epididymal fat pad, serum leptin, and serum T3 in 4-month-old mice treated for 1 month with 1 of 2 doses of T3 in the drinking water (0.1 µg/mL or 0.25 µg/mL). Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by the Student t test in 6 to 16 mice per experimental group. LPL, lipoprotein lipase; WT, wild type.

The small size of brown and white adipocytes was accompanied by abnormalities in gene expression. Adiponectin and leptin mRNAs in the WAT of Dio3−/− mice were lower than in the WAT of Dio3+/+ mice, but no change was observed in the WAT mRNA expression of Lpl, nor any increase in Ucp1 expression, an indicator of WAT “beiging.” The mRNA expression of Elovl3, a gene that is activated upon BAT recruitment (38), was significantly increased in both the WAT and BAT of Dio3−/− mice [Fig. 2(C) and 2(D)]. No changes were observed in the BAT expression of adiponectin, leptin, Ucp1, and Lpl, although leptin expression trended lower [Fig. 2(D)]. Compared with values in Dio3+/+ littermates of the same sex, serum leptin level was significantly higher in Dio3−/− female mice at 3 months of age, but significantly lower when they were 1-year-old animals [Fig. 2(E)].

Notably, the adiposity in Dio3−/− mice was extremely sensitive to T3 treatment [Fig. 2(F)]. When male mice were treated for 4 weeks with 2 different doses of T3 in the drinking water (0.1 and 0.25 µg/mL), Dio3+/+ mice exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in fat pad weight. However, white fat was absent in Dio3−/− mice treated with either dose of T3. Serum T3 levels achieved by a given dose of T3 were higher in Dio3−/− mice [Fig. 2(F)]. This experiment also revealed some differences between genotypes in the serum levels of leptin. In Dio3+/+ mice, the low dose of T3 did not result in any change in serum leptin, but the higher dose of T3 led to a marked increase in serum leptin [Fig. 2(F)]. Untreated Dio3−/− male mice showed the same serum leptin as untreated Dio3+/+ male mice. In contrast, both doses of T3 resulted in a suppression of serum leptin levels in Dio3−/− mice.

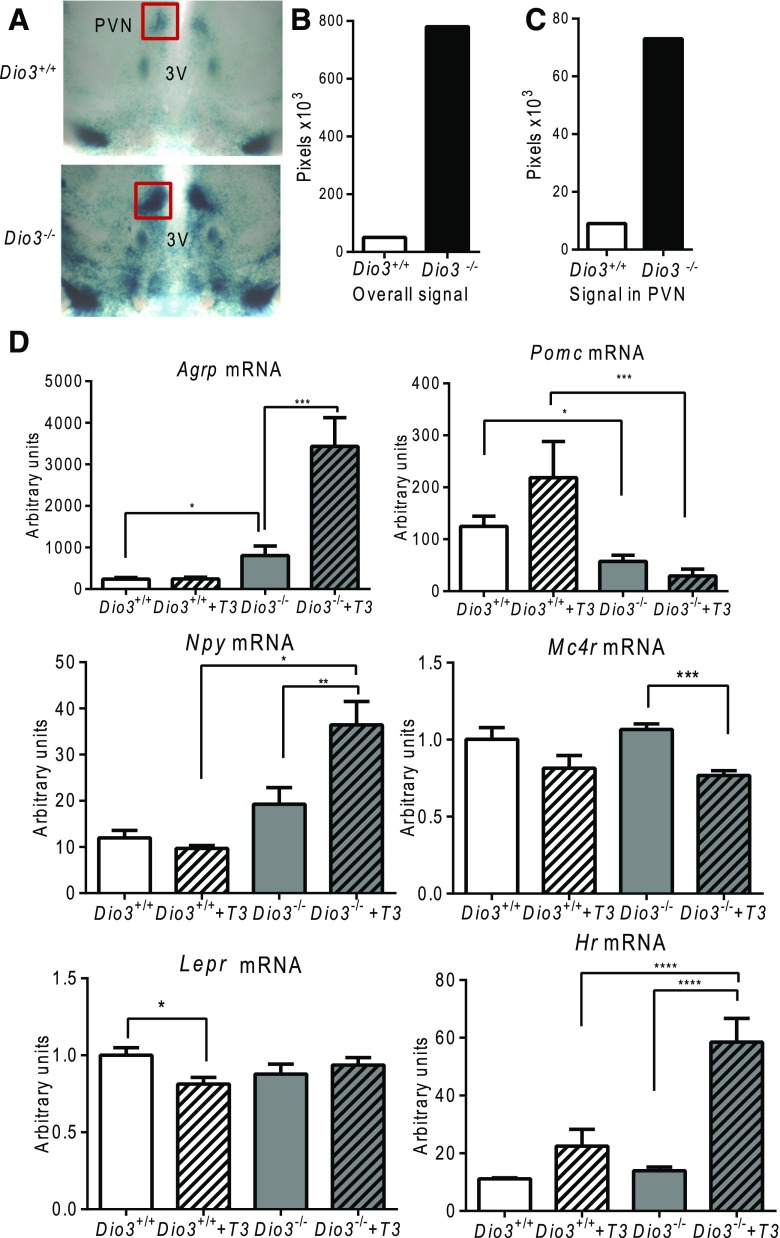

Hypothalamic hyperthyroidism in the Dio3−/− mice

Dio3 is highly expressed in the adult brain (30), and we have previously shown that the brain of Dio3−/− mice becomes increasingly hyperthyroid as the animals age (32). Thus, we investigated the hypothalamus because this brain region is critical for the control of energy balance. To assess the effects of DIO3 deficiency on hypothalamic TH action, we analyzed the β-galactosidase staining of hypothalamic sections from Dio3+/+ and Dio3−/− mice that carried the FINDT3 transgene. This transgene includes a β-galactosidase reporter, the signal of which has been shown to be very specific and markedly regulated by TH status (32). An increase in β-galactosidase staining was observed in most areas of the hypothalamus, such as the paraventricular nucleus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the supraoptic nucleus, and other hypothalamic areas [Fig. 3(A)]. Quantitative assessment shows that the staining level in Dio3−/− mice is about 10-fold higher than in control mice [Fig. 3(B) and 3(C)]. To examine the possible effects of this central hyperthyroid state on the leptin-melanocortin system, we measured hypothalamic mRNA expression of genes integral to this system in untreated mice and in mice treated with T3 for 4 weeks. Compared with male Dio3+/+ mice, male Dio3−/− mice showed increased Agrp expression and decreased Pomc expression [Fig. 3(D)]. Upon treatment with T3, these differences were exaggerated as the expression of those genes responded to T3 treatment in Dio3−/− mice, but not in Dio3+/+ mice. Expression of Npy followed a pattern similar to that of Agrp. Mc4r expression was decreased in T3-treated Dio3−/− mice, but unchanged in T3-treated Dio3+/+ mice. In contrast, Lepr expression was decreased in T3-treated Dio3+/+ mice and unchanged in T3-treated Dio3−/− mice [Fig. 3(D)]. Hypothalamic expression of Hr, a T3-regulated gene and a reliable indicator of TH status in the brain, showed a much greater response to T3 treatment in Dio3−/− mice than in Dio3+/+ mice [Fig. 3(D)].

Figure 3.

Hyperthyroid state in the hypothalamus of male Dio3−/− mice. (A) Representative β-galactosidase staining and (B, C) quantification in hypothalamic coronal sections from 10-month-old male mice. (D) Basal and effect of T3 treatment on hypothalamic mRNA expression of Agrp, Pomc, Npy, Mc4r, Lepr, and Hr in 4-month-old mice. Some of the mice were treated with T3 (0.1 μg/mL) in drinking water for 4 weeks. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test in 6 to 8 mice per experimental group. PVN, paraventricular nucleus; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus.

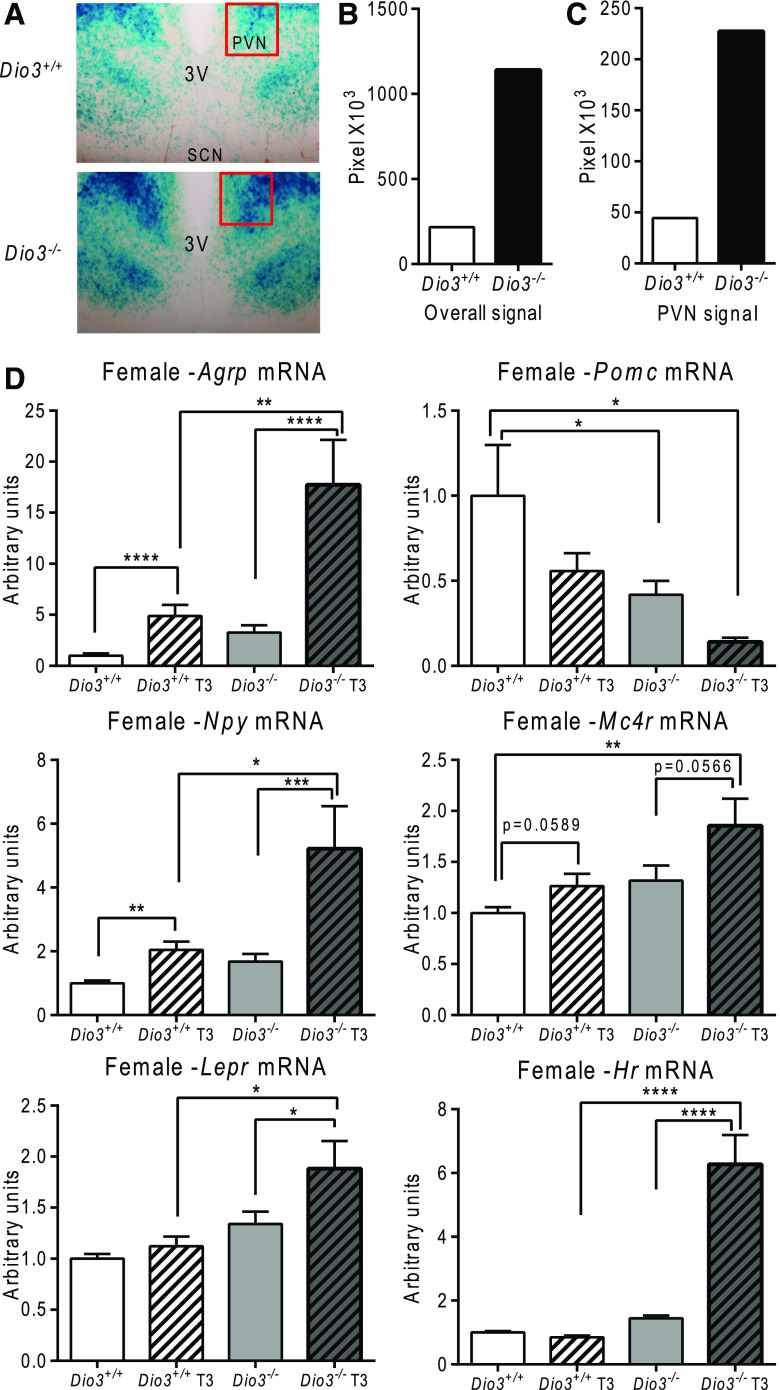

In females, comparable results were obtained. Dio3−/− females carrying the FINDT3A transgene showed increased β-galactosidase staining in the hypothalamus, including the paraventricular nucleus [Fig. 4(A–C)]. Similarly to males, at baseline, Dio3−/− females manifested elevated expression of Agrp and Npy, and reduced expression of Pomc, and this profile was accentuated when the animals were treated with T3 [Fig. 4(D)]. Contrary to the results obtained in males, expression of the Lepr and Mc4r trended higher in Dio3−/− females compared with control females, and this tendency was particularly significant when the animals were treated with T3 [Fig. 4(D)]. Overall, these results suggest an abnormal set point of the leptin-melanocortin system in Dio3−/− mice, with increased sensitivity to TH and with subtle sexual differences in terms of how the male and female mice are affected.

Figure 4.

Hyperthyroid state in the hypothalamus of female Dio3−/− mice. (A) Representative β-galactosidase staining and (B, C) quantification in hypothalamic coronal sections from 6-month-old female mice. (D) Basal and effect of T3 treatment on hypothalamic mRNA expression of Agrp, Pomc, Npy, Mc4r, Lepr, and Hr in 4-month-old mice. Some of the mice were treated with T3 (0.1 μg/mL) in drinking water for 4 weeks. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test in 6 to 8 mice per experimental group. PVN, paraventricular nucleus.

Body composition and EE in Dio3−/− mice

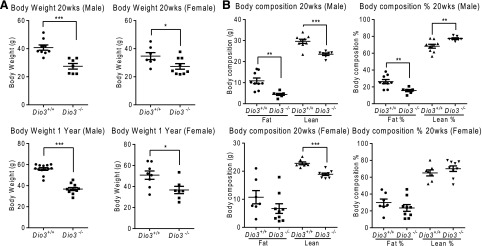

In addition to being lean, we have previously shown that Dio3−/− mice are growth retarded (30). Consistent with that previous observation, the body weight of 20-week-old and 1-year-old Dio3−/− mice was reduced in both adult male and female mice [Fig. 5(A)]. Analysis of body composition revealed that male Dio3−/− mice exhibit an increased percentage of lean mass and a decreased percentage of fat mass [Fig. 5(B)]. A similar trend, although not statistically significant, was observed in female Dio3−/− mice [Fig. 5(B)].

Figure 5.

Decreased body weight and altered body composition in Dio3−/− mice. (A) Body weight in 20-week-old and 1-year-old mice of both sexes. (B) Lean and fat mass as a percentage of body weight in 20-week-old and 1-year-old mice of both sexes. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by the Student t test in 7 to 10 mice per experimental group.

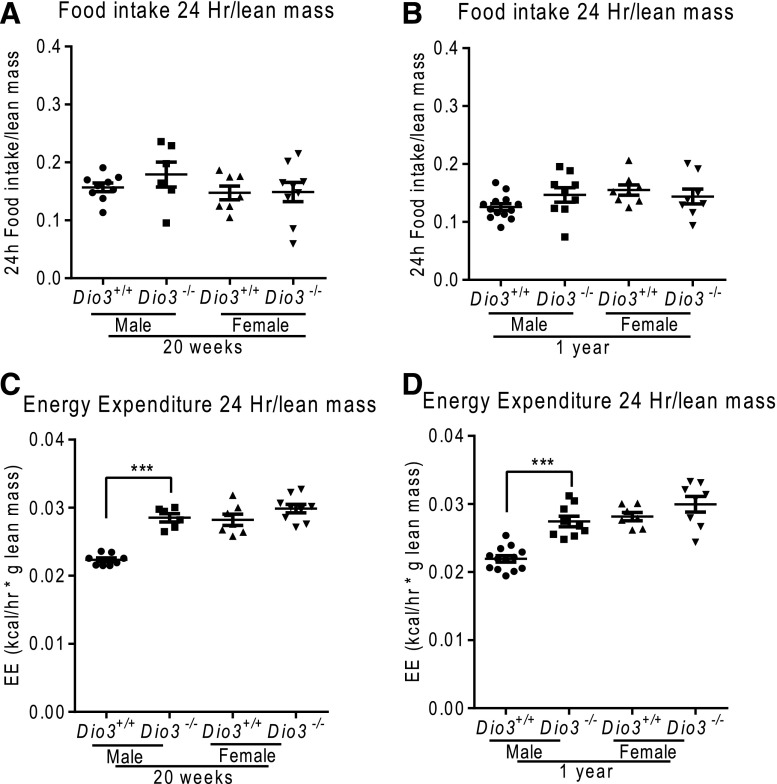

We then analyzed the EE parameters of Dio3−/− mice using metabolic cages (see Supplemental Data (1.4MB, pdf) for full results). Despite their reduced body weight, food intake was not altered in Dio3−/− mice of either sex at either 20 weeks or 1 year of age [Fig. 6(A) and 6(B)]. Relative EE was increased in male Dio3−/− mice, but this result was not significant in females [Fig. 6(C) and 6(D)]. We performed a regression analysis to correct EE by lean mass. There was a linear relation between lean mass vs EE in the 20-week-old Dio3−/− male mice [Supplemental Fig. 1(A) (1MB, eps) ]. Regression adjusted values showed an increase in EE in Dio3−/− male mice at this age [Dio3+/+ 24-hour EE, 0.6944 ± 0.019940 vs Dio3−/− 24-hour EE, 0.7562 ± 0.01174 cal/h; P = 0.01; Supplemental Fig. 1(B) (1.5MB, eps) ].

Figure 6.

Food intake and EE in Dio3−/− mice. (A) Daily food intake in 20-week-old mice of both sexes. (B) Daily food intake in 1-year-old mice of both sexes. (C) EE in 20-week-old mice of both sexes. (D) EE in 1-year-old mice of both sexes. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. ***P < 0.001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ mice as determined by the Student t test in 6 to 15 mice per experimental group.

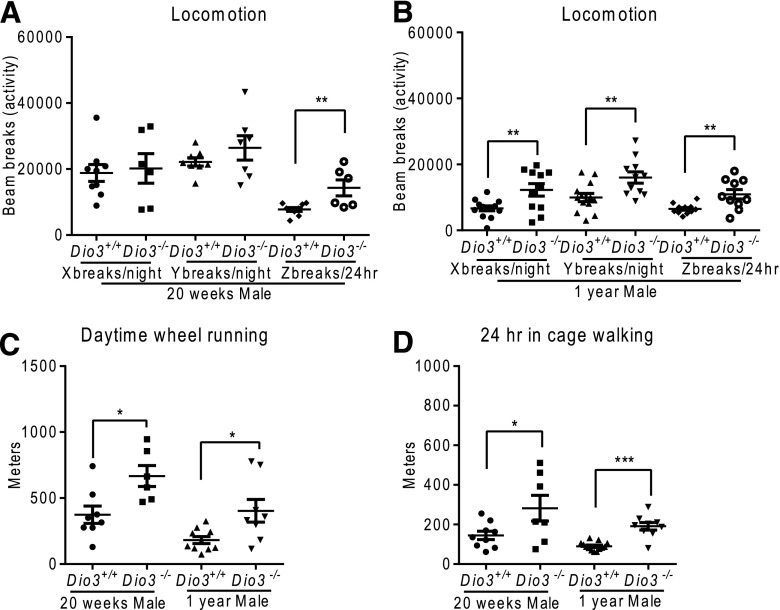

Overall physical activity was markedly increased in DIO3-deficient mice. At 20 weeks of age, Dio3−/− male but not female mice had higher Z breaks (rising on hind legs) than Dio3+/+ mice [Fig. 7(A)]. Strikingly, the number of X, Y, and Z breaks in 1-year-old Dio3−/− male mice were all higher than those in control male mice [Fig. 7(B)]. Distances run in the wheel and traveled in the cage were both higher in Dio3−/− male mice at 20 weeks and 1 year of age [Fig. 7(C) and 7(D)]. The number of Z breaks in 20-week-old female Dio3−/− mice was also higher than that in Dio3+/+ mice. However, at 1 year of age, no difference between genotypes was observed in the number of X and Y breaks in female mice. Running distances of Dio3−/− female mice were mildly increased at 20 weeks and significantly increased at 1 year old. We did not observe a change in the distance walked by Dio3−/− female mice (Supplemental Fig. 2 (1.5MB, eps) ).

Figure 7.

Increased physical activity in Dio3−/− male mice. (A) Locomotion in 20-week-old and (B) 1-year-old male mice. (C) Wheel running and (D) walking distances in 20-week-old and 1-year-old male mice. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ as determined by the Student t test in 6 to 11 mice per experimental group.

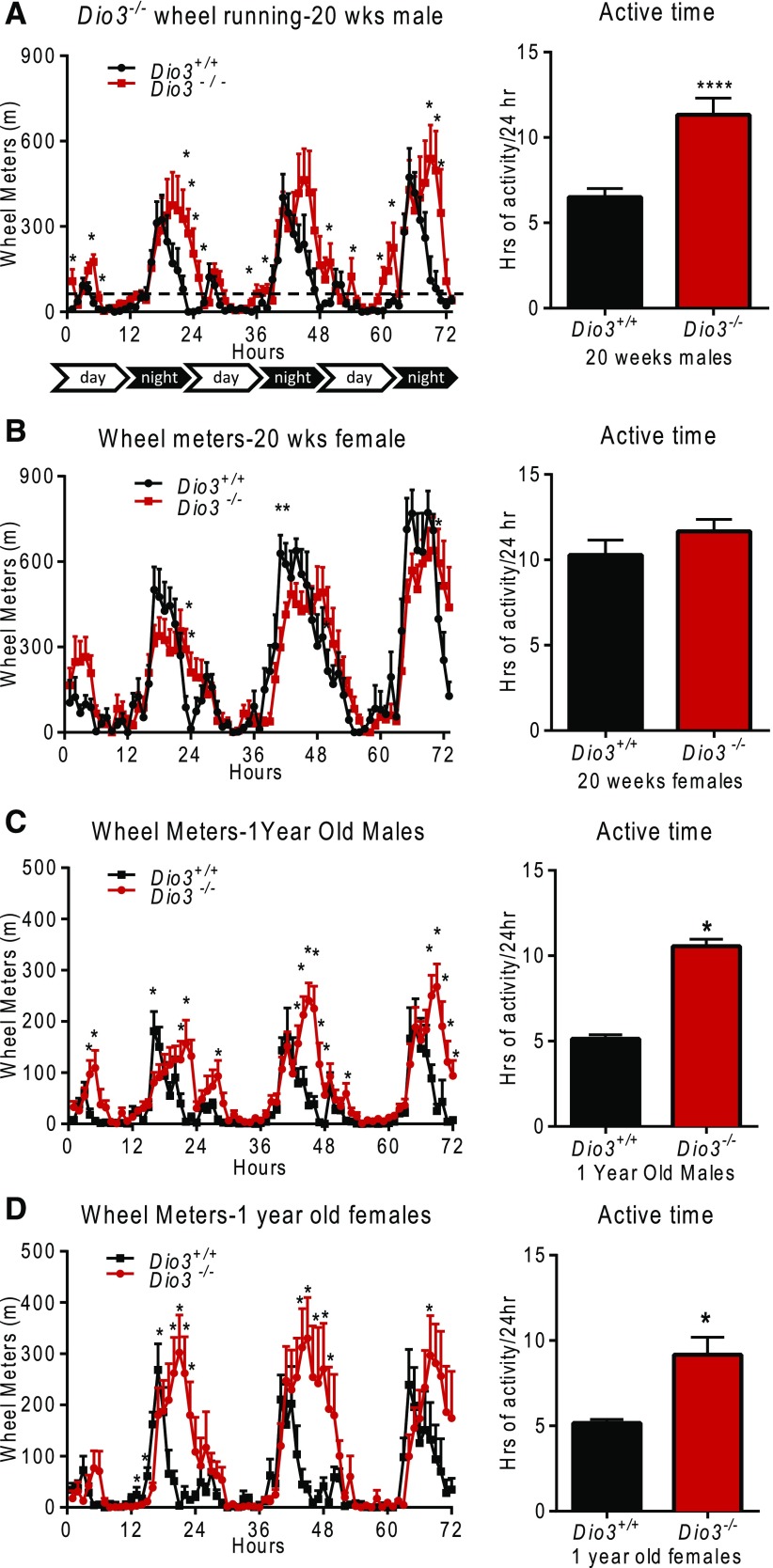

Day-night activity changes in Dio3−/− mice

The increased physical activity of Dio3−/− mice was due in part to an expansion in time across the daily L/D cycles (Fig. 8). The wheel running time frame was consistent with the L/D cycle in control mice. However, 20-week-old Dio3−/− male mice were noted to have an extended running period on the wheel that lasted 4 hours longer than in Dio3+/+ mice [Fig. 8(A)]. The circadian pattern of wheel running of 20-week-old female Dio3−/− mice showed no difference from Dio3+/+ mice [Fig. 8(B)]. We also tested the physical activity of 1-year-old mice. At this age, both male and female Dio3−/− mice showed increased running time and an extended dark-cycle of physical activity, similar to 20-week-old male Dio3−/− mice [Fig. 8(C) and 8(D)]. The time frame of pedal walking time was also consistent with the L/D cycle in the control mice. In contrast, the daily walking activity patterns of Dio3−/− mice showed increased active time and walking meters in both day and night cycles. This was observed in 20-week-old Dio3−/− mice of both sexes and in 1-year-old Dio3−/− males (Supplemental Fig. 3 (1.8MB, eps) ).

Figure 8.

Daily profile of wheel running in male Dio3−/− mice. Wheel running profile (left side) and total hours of daily activity (right side) in (A) 20-week-old male and (B) female mice and in (C) 1-year-old male and (D) female mice. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; Dio3−/− vs Dio3+/+ as determined by the Student t test in 6 to 9 mice per experimental group.

The sleep time is consistent with the activity results. Both 20-week-old and 1-year old Dio3−/− male mice exhibited marked decreases in sleeping time [Supplemental Fig. 4(A) (912.9KB, eps) ]. Reduced sleeping time was also observed in 1-year-old Dio3−/− females, with a trend toward that result in 20-week-old female mice [Supplemental Fig. 4(B) (912.9KB, eps) ]. We also analyzed the hypothalamic expression of circadian-related genes Per2 and Rora (39–42)(Supplemental Fig. 5 (1MB, eps) ). A decrease in Rora expression in the hypothalamus of Dio3−/− females was the only parameter that was close to reaching statistical significance (Supplemental Fig. 5 (1MB, eps) ). However, these data have limited significance, given that the potential circadian alterations in Dio3−/− mice were not anticipated and tissues were not harvested at particular times of the circadian cycle.

Discussion

TH has long been recognized as a major factor regulating human metabolism. These metabolic effects have been attributed to the direct actions of TH on peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle, liver, fat (12, 43), and heart (44). Most recently, the concept has emerged that TH metabolic effects are also mediated via CNS processes (23, 45–47).

In this regard, although Dio3−/− mice exhibit decreased serum levels of TH (27, 30), we have shown that their CNSs manifest a state of thyrotoxicosis that increases during adult life (48). We hypothesize that this elevated level of TH action may affect hypothalamic systems and cause an abnormal regulation of energy balance that alters their susceptibility to obesity. We indeed observed that Dio3−/− mice of both sexes exhibit reduced white and brown adipocyte size, and a reduction in fat mass that becomes more prominent with advancing age. This is accompanied by changes in the WAT expression of genes related to lipid metabolism, but not with BAT expression changes in genes related to thermogenesis.

Given that adult expression of DIO3 is high in the brain but negligible in WAT and BAT, the adipose tissue phenotype of Dio3−/− mice is likely the result of enhanced levels of TH signaling in multiple regions of the hypothalamus. As a consequence, many important hypothalamic circuitries regulating energy balance may be altered, including the leptin-melanocortin system. Consistent with a previous study that used hypothalamic administration of T3 (23), we now show that enhanced local T3 action resulting from the lack of DIO3 activity leads to increased expression of Agrp and Npy mRNAs and decreased levels of Pomc mRNA in the hypothalamus of Dio3−/− mice. This abnormal regulation of gene expression was exacerbated by T3 treatment in Dio3−/− mice, but not in Dio3+/+ mice, underscoring the regulatory role of DIO3 on T3 action directly in these neurons or in hypothalamic circuitries that influence their physiology. Paradoxically, in light of the observed reduction in adiposity, serum leptin levels were normal in young Dio3−/− male mice and elevated in young females. In older females, serum leptin was decreased, consistent with their reduced fat mass. Taken together, these results reveal abnormalities in the setup and regulation of the leptin-melanocortin system that may be the result of enhanced TH signaling in the hypothalamus during development and in adulthood.

The abnormalities in the leptin-melanocortin parameters of Dio3−/− mice of both sexes, however, do not explain the lean phenotype of these animals. An increase in Agrp/Npy expression should be associated with increased food intake, whereas a decrease in Pomc expression should be associated with decreased EE. The anticipated results of both effects would be increased adiposity, but the opposite is observed. Dio3−/− mice show unchanged food intake, although they are smaller, and increased EE per lean mass (although the latter parameter, after regression analysis, is only statistically significant in young adult males). This suggests that the leptin-melanocortin system of Dio3−/− mice is abnormally programmed, probably because of developmental thyrotoxicosis, and target neurons may have reduced sensitivity to AGRP and/or MSH. The only measured parameter that can explain the resultant lean phenotype of Dio3−/− mice is the enhanced physical activity. Male Dio3−/− mice travel longer distances than Dio3+/+ littermates via in-cage walking and wheel running, as well as demonstrate a prolongation of their activity periods. This increased level of physical activity, which is consistent with clinical observations in hyperthyroid individuals (49, 50), appears to counteract the observed obesogenic effects of enhanced TH action on the melanocortin system and those of the peripheral hypothyroid state, and likely explains the observed phenotype of reduced adiposity. Thus, the leaner phenotype in older Dio3−/− mice is the consequence of longer periods of enhanced physical activity. We have shown that essentially all regions in the Dio3−/− brain manifest increased levels of TH signaling during adult age (32); thus, multiple areas of the central nervous system may be involved in this phenotype. An interesting aspect of the increased physical activity of Dio3−/− mice is that it appears to be partially due to expanded circadian cycles of activity during the dark phase. Compared with control littermates, Dio3−/− mice start earlier and end later their physical activity at the beginning and end of the dark cycle, respectively. In addition, their sleeping time is very substantially reduced. This raises the possibility that the enhanced TH action resulting from DIO3 deficiency may be exerting functional effects on hypothalamic systems that regulate the circadian clock. This effect may be related to the observation that Dio3 exhibits a circadian pattern of expression in the adrenal gland of mice from certain genetic backgrounds (51), as well as a seasonal pattern of expression in the hypothalamus of birds and mammals (52, 53). Our initial results regarding the expression of genes involved in the regulation of the circadian rhythm do not show overt abnormalities, but a circadian phenotype was not anticipated, and in-depth studies will require the analysis of the suprachiasmatic nucleus at different time points of the L/D cycle. This may be the subject of future studies.

Our results demonstrate that the effects of DIO3 deficiency on several parameters of energy balance are more pronounced in male mice than in females. This sexual dimorphism is also consistent with the fact that the hypothalamus, largely the origin of the behavioral patterns analyzed here, is a brain region particularly rich in sexually dimorphic features at the molecular, cellular, and functional levels (54–56). A very recent study reported that sex-related differences in physical activity, EE, and the development of obesity are driven by a subpopulation of Pomc neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (57). Our results demonstrate that the prominent effects of TH on these metabolic systems do not negate this basic sexually dimorphic biological pattern.

Although the consequences of the central effects of TH provide a likely explanation for the decreased adiposity in Dio3−/− mice, their systemic hypothyroidism may also be a factor. In contrast to humans, adult hypothyroidism in rodent models is not accompanied by an increase in fat mass. Different investigators have reported no change and even a decrease in adiposity in pharmacological and thyroidectomy rat models of hypothyroidism as a result of metabolic adaptation to the reduced levels of TH (58–62). Although the hypothyroidism in those models is much more severe than the hypothyroidism observed in Dio3−/− mice, those previous findings raise the possibility that the systemic hypothyroidism of Dio3−/− mice may also partially contribute to their decreased adiposity.

One intriguing possibility is that characteristics of DIO3-deficient mice resemble some traits of human attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A recent study has shown that elevated levels of TH during development (which also occurs in Dio3−/− mice) are associated with increased risk of ADHD in humans (63). −−Patients with ADHD are characterized by hyperactivity and impulsive behavior, as well as disrupted circadian rhythms and sleep patterns, and there is a higher prevalence of ADHD in males than in females (64, 65)—traits similar to those observed in Dio3−/− mice. In addition, our findings build on recent work that indicated increased locomotor activity of DIO3-deficient mice in the context of anxiety tests (61). The present observations demonstrate that hyperactivity in these animals is consistent across time and is not the transient result of the contextual environment in which those tests are performed.

We show that in DIO3-deficient mice, enhanced TH signaling in the CNS, including the hypothalamus, affects 2 important determinants of energy balance and adiposity: physical activity and the leptin-melanocortin system. These effects appear to be antiobesogenic and obesogenic, respectively, with the former prevailing in global DIO3 deficiency. To elucidate the distinct metabolic consequences of TH action in specific brain regions, future studies will require the use of mouse models of conditional inactivation of DIO3. Given that more than 82.7% of overweight Americans are unable to maintain a 10% weight loss for 1 year or longer as a result of body weight regain (62), body weight regain is currently the most challenging problem to obesity treatment. Our findings have important implications for the development of novel strategies to control and prevent obesity by manipulating the TH level in the brain. In summary, our results define multiple roles for TH in the central regulation of physiological processes that influence physical activity and energy balance. Additional work with mouse models used in our study and other mouse models will precisely define those roles and their significance for human pathology, opening new possibilities for clinical interventions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Frederic Flamant for the FINDT3 mouse strains. Our studies used the Histopathology, Physiology and Molecular Phenotyping Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation facilities at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, which are recipients of COBRE grants P30GM103392 and P30GM106391 (R. E. Friesel and D. M. Wojchowski, PIs).

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants DK054716 (D.L.S.G.), MH083220 (A.H.), DK095908 (A.H.), and MH096050 (A.H.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ADHD

- attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder

- AGRP

- agouti-related peptide

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- CNS

- central nervous system

- DIO3

- type 3 deiodinase

- EE

- energy expenditure

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- L/D

- light-dark

- mRNA

- messenger RNA

- POMC

- proopiomelanocortin

- T3

- triiodothyronine

- T4

- thyroxine

- TH

- thyroid hormone

- UCP

- uncoupling protein

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

References

- 1.Kim B. Thyroid hormone as a determinant of energy expenditure and the basal metabolic rate. Thyroid. 2008;18(2):141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollenberg AN, Forrest D. The thyroid and metabolism: the action continues. Cell Metab. 2008;8(1):10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner A, Mittag J. Thyroid hormone and the central control of homeostasis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;49(1):R29–R35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Lazar MA. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:439–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goglia F, Moreno M, Lanni A. Action of thyroid hormones at the cellular level: the mitochondrial target. FEBS Lett. 1999;452(3):115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillar TM, Seitz HJ Thyroid hormone and gene expression in the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory function. Eur J Endocrinol 1997;136(3):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutvei A, Kuzela S, Nelson BD Control of mitochondrial transcription by thyroid hormone. Eur J Biochem 1989;180(1):235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanni A, Moreno M, Lombardi A, Goglia F. Thyroid hormone and uncoupling proteins. FEBS Lett. 2003;543(1–3):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox CS, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Murabito JM, Seely EW, Pearce EN, Vasan RS. Relations of thyroid function to body weight: cross-sectional and longitudinal observations in a community-based sample. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(6):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray GA, Fisher DA, Chopra IJ. Relation of thyroid hormones to body-weight. Lancet. 1976;1(7971):1206–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roef G, Lapauw B, Goemaere S, Zmierczak HG, Toye K, Kaufman JM, Taes Y Body composition and metabolic parameters are associated with variation in thyroid hormone levels among euthyroid young men. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167(5):719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva JE. Thermogenic mechanisms and their hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(2):435–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullur R, Liu YY, Brent GA. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(2):355–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, Yim JY, Park MJ, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol. 2012;57(1):150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha RA, Singh BK, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone regulation of hepatic lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(10):538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellentani S, Scaglioni F, Marino M, Bedogni G. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28(1):155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha RA, You SH, Zhou J, Siddique MM, Bay BH, Zhu X, Privalsky ML, Cheng SY, Stevens RD, Summers SA, Newgard CB, Lazar MA, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone stimulates hepatic lipid catabolism via activation of autophagy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2428–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvatore D, Simonides WS, Dentice M, Zavacki AM, Larsen PR. Thyroid hormones and skeletal muscle--new insights and potential implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(4):206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zorzano A, Palacín M, Gumà A. Mechanisms regulating GLUT4 glucose transporter expression and glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183(1):43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christoffolete MA, Linardi CC, de Jesus L, Ebina KN, Carvalho SD, Ribeiro MO, Rabelo R, Curcio C, Martins L, Kimura ET, Bianco AC. Mice with targeted disruption of the Dio2 gene have cold-induced overexpression of the uncoupling protein 1 gene but fail to increase brown adipose tissue lipogenesis and adaptive thermogenesis. Diabetes. 2004;53(3):577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro MO, Bianco SD, Kaneshige M, Schultz JJ, Cheng SY, Bianco AC, Brent GA. Expression of uncoupling protein 1 in mouse brown adipose tissue is thyroid hormone receptor-beta isoform specific and required for adaptive thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010;151(1):432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.López M, Varela L, Vázquez MJ, Rodríguez-Cuenca S, González CR, Velagapudi VR, Morgan DA, Schoenmakers E, Agassandian K, Lage R, Martínez de Morentin PB, Tovar S, Nogueiras R, Carling D, Lelliott C, Gallego R, Oresic M, Chatterjee K, Saha AK, Rahmouni K, Diéguez C, Vidal-Puig A. Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nat Med. 2010;16(9):1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krashes MJ, Shah BP, Madara JC, Olson DP, Strochlic DE, Garfield AS, Vong L, Pei H, Watabe-Uchida M, Uchida N, Liberles SD, Lowell BB. An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AgRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature. 2014;507(7491):238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coppola A, Liu ZW, Andrews ZB, Paradis E, Roy MC, Friedman JM, Ricquier D, Richard D, Horvath TL, Gao XB, Diano S. A central thermogenic-like mechanism in feeding regulation: an interplay between arcuate nucleus T3 and UCP2. Cell Metab. 2007;5(1):21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bianco AC, Kim BW. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(10):2571–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charalambous M, Hernandez A Genomic imprinting of the type 3 thyroid hormone deiodinase gene: regulation and developmental implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(7):3946–3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sagar GD, Gereben B, Callebaut I, Mornon JP, Zeöld A, Curcio-Morelli C, Harney JW, Luongo C, Mulcahey MA, Larsen PR, Huang SA, Bianco AC. The thyroid hormone-inactivating deiodinase functions as a homodimer. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(6):1382–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez ME, Karaczyn A, Stohn JP, Donnelly WT, Croteau W, Peeters RP, Galton VA, Forrest D, St Germain D, Hernandez A. The type 3 deiodinase is a critical determinant of appropriate thyroid hormone action in the developing testis. Endocrinology. 2016;157(3):1276–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, St Germain D. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Liao XH, Van Sande J, Refetoff S, Galton VA, St Germain DL. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency results in functional abnormalities at multiple levels of the thyroid axis. Endocrinology. 2007;148(12):5680–5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez A, Quignodon L, Martinez ME, Flamant F, St Germain DL. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency causes spatial and temporal alterations in brain T3 signaling that are dissociated from serum thyroid hormone levels. Endocrinology. 2010;151(11):5550–5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395(6704):763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers MG Jr, Olson DP. Central nervous system control of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491(7424):357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quignodon L, Legrand C, Allioli N, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Bernal J, Samarut J, Flamant F. Thyroid hormone signaling is highly heterogeneous during pre- and postnatal brain development. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33(2):467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiyala KJ, Schwartz MW. Toward a more complete (and less controversial) understanding of energy expenditure and its role in obesity pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2011;60(1):17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiyala KJ, Morton GJ, Leroux BG, Ogimoto K, Wisse B, Schwartz MW. Identification of body fat mass as a major determinant of metabolic rate in mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1657–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westerberg R, Månsson JE, Golozoubova V, Shabalina IG, Backlund EC, Tvrdik P, Retterstøl K, Capecchi MR, Jacobsson A. ELOVL3 is an important component for early onset of lipid recruitment in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):4958–4968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko CH, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R271–R277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalsbeek A, Scheer FA, Perreau-Lenz S, La Fleur SE, Yi CX, Fliers E, Buijs RM. Circadian disruption and SCN control of energy metabolism. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(10):1412–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross AW, Helfer G, Russell L, Darras VM, Morgan PJ. Thyroid hormone signalling genes are regulated by photoperiod in the hypothalamus of F344 rats. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalsbeek A, Buijs RM, van Schaik R, Kaptein E, Visser TJ, Doulabi BZ, Fliers E. Daily variations in type II iodothyronine deiodinase activity in the rat brain as controlled by the biological clock. Endocrinology. 2005;146(3):1418–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Short KR, Nygren J, Barazzoni R, Levine J, Nair KST. T(3) increases mitochondrial ATP production in oxidative muscle despite increased expression of UCP2 and -3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(5):E761–E769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(5):704–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fliers E, Klieverik LP, Kalsbeek A. Novel neural pathways for metabolic effects of thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(4):230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werneck de Castro JP, Fonseca TL, Ueta CB, McAninch EA, Abdalla S, Wittmann G, Lechan RM, Gereben B, Bianco AC. Differences in hypothalamic type 2 deiodinase ubiquitination explain localized sensitivity to thyroxine. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Foppen E, Su Y, Bisschop PH, Kalsbeek A, Fliers E, Boelen A. Metabolic effects of chronic T3 administration in the hypothalamic paraventricular and ventromedial nucleus in male rats. Endocrinology. 2016;157(10):4076–4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez ME, Charalambous M, Saferali A, Fiering S, Naumova AK, St Germain D, Ferguson-Smith AC, Hernandez A. Genomic imprinting variations in the mouse type 3 deiodinase gene between tissues and brain regions. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(11):1875–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss RE, Stein MA, Trommer B, Refetoff S. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and thyroid function. J Pediatr. 1993;123(4):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hauser P, Soler R, Brucker-Davis F, Weintraub BD. Thyroid hormones correlate with symptoms of hyperactivity but not inattention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22(2):107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labialle S, Yang L, Ruan X, Villemain A, Schmidt JV, Hernandez A, Wiltshire T, Cermakian N, Naumova AK. Coordinated diurnal regulation of genes from the Dlk1-Dio3 imprinted domain: implications for regulation of clusters of non-paralogous genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bechtold DA, Loudon AS. Hypothalamic thyroid hormones: mediators of seasonal physiology. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3605–3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barrett P, Ebling FJ, Schuhler S, Wilson D, Ross AW, Warner A, Jethwa P, Boelen A, Visser TJ, Ozanne DM, Archer ZA, Mercer JG, Morgan PJ. Hypothalamic thyroid hormone catabolism acts as a gatekeeper for the seasonal control of body weight and reproduction. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3608–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu X, Coats JK, Yang CF, Wang A, Ahmed OM, Alvarado M, Izumi T, Shah NM. Modular genetic control of sexually dimorphic behaviors. Cell. 2012;148(3):596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang CF, Chiang MC, Gray DC, Prabhakaran M, Alvarado M, Juntti SA, Unger EK, Wells JA, Shah NM. Sexually dimorphic neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus govern mating in both sexes and aggression in males. Cell. 2013;153(4):896–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scott N, Prigge M, Yizhar O, Kimchi T. A sexually dimorphic hypothalamic circuit controls maternal care and oxytocin secretion. Nature. 2015;525(7570):519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burke LK, Doslikova B, D’Agostino G, Greenwald-Yarnell M, Georgescu T, Chianese R, Martinez de Morentin PB, Ogunnowo-Bada E, Cansell C, Valencia-Torres L, Garfield AS, Apergis-Schoute J, Lam DD, Speakman JR, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Rochford JJ, Myers MG, Evans ML, Heisler LK. Sex difference in physical activity, energy expenditure and obesity driven by a subpopulation of hypothalamic POMC neurons. Mol Metab. 2016;5(3):245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curcio C, Lopes AM, Ribeiro MO, Francoso OA Jr, Carvalho SD, Lima FB, Bicudo JE, Bianco AC. Development of compensatory thermogenesis in response to overfeeding in hypothyroid rats. Endocrinology. 1999;140(8):3438–3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Syed MA, Thompson MP, Pachucki J, Burmeister LA The effect of thyroid hormone on size of fat depots accounts for most of the changes in leptin mRNA and serum levels in the rat. Thyroid. 1999;9(5):503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karakoc A, Ayvaz G, Taneri F, Toruner F, Yilmaz M, Cakir N, Arslan M. The effects of hypothyroidism in rats on serum leptin concentrations and leptin mRNA levels in adipose tissue and relationship with body fat composition. Endocr Res. 2004;30(2):247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aragão CN, Souza LL, Cabanelas A, Oliveira KJ, Pazos-Moura CC. Effect of experimental hypo- and hyperthyroidism on serum adiponectin. Metabolism. 2007;56(1):6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klieverik LP, Coomans CP, Endert E, Sauerwein HP, Havekes LM, Voshol PJ, Rensen PC, Romijn JA, Kalsbeek A, Fliers E. Thyroid hormone effects on whole-body energy homeostasis and tissue-specific fatty acid uptake in vivo. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5639–5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andersen SL, Laurberg P, Wu CS, Olsen J. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in children born to mothers with thyroid dysfunction: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121(11):1365–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coogan AN, Baird AL, Popa-Wagner A, Thome J. Circadian rhythms and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The what, the when and the why. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;67:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nøvik TS, Hervas A, Ralston SJ, Dalsgaard S, Rodrigues Pereira R, Lorenzo MJ; ADORE Study Group . Influence of gender on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Europe--ADORE. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(Suppl 1):I15–I24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]