Abstract

Context:

Inflammatory pathways may impair central regulatory networks involving gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neuron activity. Studies in humans are limited by the lack of human GnRH neuron cell lines.

Objective:

To establish an in vitro model of human GnRH neurons and analyze the effects of proinflammatory cytokines.

Design:

The primary human fetal hypothalamic cells (hfHypo) were isolated from 12-week-old fetuses. Responsiveness to kisspeptin, the main GnRH neurons' physiological regulator, was evaluated for biological characterization. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was used as a proinflammatory stimulus. Main Outcome Measures: Expression of specific GnRH neuron markers by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, flow cytometry, and immunocytochemistry analyses; and GnRH-releasing ability and electrophysiological changes in response to kisspeptin.

Results:

The primary hfHypo showed a high percentage of GnRH-positive cells (80%), expressing a functional kisspeptin receptor (KISS1R) and able to release GnRH in response to kisspeptin. TNF-α exposure determined a specific inflammatory intracellular signaling and reduced GnRH secretion, KISS1R expression, and kisspeptin-induced depolarizing effect. Moreover, hfHypo possessed a primary cilium, whose assembly was inhibited by TNF-α.

Conclusion:

The hfHypo cells represent a novel tool for investigations on human GnRH neuron biology. TNF-α directly affects GnRH neuron function by interfering with KISS1R expression and ciliogenesis, thereby impairing kisspeptin signaling.

Précis: Primary human GnRH neurons have been isolated and characterized. Exposing these cells to TNF-α directly affected their function by interfering with KISS1R expression and ciliogenesis.

The pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) into the hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal circulation is the main requirement for the initiation and maintenance of reproductive function. Very early on during the human ontogenesis, GnRH-secreting neurons originate from progenitors, located in the olfactory placode, migrate along the olfactory nerve route and reach their final destination within the hypothalamus (1). Human cells isolated from the olfactory epithelium of an 8-week-old fetus can respond to odorant stimuli and secrete GnRH in vitro (2). Regardless of their final location in the brain, GnRH-immunoreactive perikarya have been immunohistochemically detected in the fetal hypothalamus by the ninth week of gestation (3). This is the earliest time evaluated for GnRH positivity in human hypothalamus; therefore, a more precocious development of the GnRH system in the human brain cannot be ruled out. Within the hypothalamus, GnRH neurons are present in a very small number (800 to 2000 cells) in close proximity of the third ventricle and with a peculiar topographical distribution. As derived from combined results of different studies in the human (4), the majority of GnRH-positive neurons are located within the preoptic region and in the medio-basal hypothalamus (infundibular region).

The activity of GnRH neurons is documented during the gestational, perinatal, and postnatal period. It is then dampened until permissive signals determine their reawakening at the time of puberty onset. Several internal (cortical and neuroendocrine) and external (behavioral, ambience-dependent) signals are integrated at central level to finely regulate the human GnRH system activity. In particular, today’s consensus is that a discrete hypothalamic population of kisspeptin-synthesizing neurons mediate a range of hormonal and metabolic inputs known to regulate GnRH secretion (5). Kisspeptin, the active protein encoded by the KISS1 gene, is regarded as the most potent stimulator of GnRH/gonadotropin release in different species, including humans (6), with about 90% of GnRH neurons expressing the KISS1 receptor (KISS1R/GPR54). However, besides the intermediate regulatory network, the GnRH system may be under the direct control of circulating hormonal and metabolic cues. Indeed, GnRH neurons projects dendrites in circumventricular regions, outside the blood brain barrier (7). Although it is recognized that multiple factors related to metabolic derangements may perturb central neuroendocrine mechanisms of the reproductive axis (8), their direct action is poorly investigated.

Over the past decades, several studies have shown that metabolic dysfunctions strictly associate to overnutrition-related inflammation in peripheral organs, such as visceral adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver (9). In addition to peripheral inflammation, low-grade inflammation in the medio-basal hypothalamus of high-fat diet (HFD)–induced animal models of obesity (10) or metabolic syndrome (MetS) (11) may cause alterations in key brain areas controlling energy homeostasis (10) and reproduction (11). Accordingly, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is reputed as an additional clinical manifestation of MetS in both the animal model (11) and in humans (12). To date, little is known about the effects of circulating proinflammatory molecules on human GnRH neurons. Knowledge about the regulatory network governing GnRH system, in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions, is based on laboratory animals, in particular rodents. Moreover, in vitro studies on GnRH neuron biology used immortalized cell lines either of mouse (13, 14) or rat (15) origin. Hence, the primary objective of this study is to establish a cellular model of GnRH neurons of human origin and analyze the effects of proinflammatory cytokines on their biological properties. We believe that such a model could represent a valuable tool for investigating those factors that may directly influence human GnRH neuron function.

Materials and Methods

Human fetal hypothalamic cells isolation

Human fetuses biopsies were obtained from therapeutic medical abortions after women’s informed consent and the approval of the Local Ethical Committee (Protocol Number 678304, University of Florence). Human fetal hypothalamic (hfHypo) tissue of the infundibular region was dissected from brain of 3 human fetuses aged 12 weeks (2 females and 1 male). Cell isolation was performed under sterile conditions from tissue specimens fragmented and enzymatically digested using 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The cell suspensions were mechanically dispersed by pipetting in Coon's modified Ham’s F12 medium (Euroclone, Milan, Italy) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and cultured under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Isolation of total RNA from cells and complementary DNA synthesis was carried out as previously detailed (16). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed according to the fluorescent TaqMan methodology using the 18S ribosomal RNA as reference gene for normalization, as previously described (16). Primers and probes for the target genes were predeveloped assays (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA; Table 1). Amplification and detection were performed with the MyIQ2 Two-Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Table 1.

Taqman Gene Expression Assay Used for qRT-PCR Analysis

| Gene Name | Assay ID |

|---|---|

| β-tubulin III | Hs00801390_s1 |

| MAP2, microtubule-associated protein-2 | Hs00234140_m1 |

| Olig2, oligodendrocyte transcription factor-2 | Hs00377820_m1 |

| GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein | Hs00157674_m1 |

| SOX11, SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 11 | Hs00846583_s1 |

| GnRH | Hs00171272_m1 |

| KISS1 | Hs00158486_m1 |

| KISS1R | Hs00261399_m1 |

| CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone | Hs00174941_m1 |

| TAC3, tachykinin-3 | Hs00203109_m1 |

| TAC3R, TAC3 receptor | Hs00357277_m1 |

| FGFR1, fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 | Hs00241111_m1 |

| SEMA3A, semaphorin 3A | Hs00173810_m1 |

| SEMA3F, semaphorin 3F | Hs00188273_m1 |

| NRP2, neuropilin 2 | Hs00187290_m1 |

| AR, androgen receptor | Hs00171172_m1 |

| ER-α, estrogen receptor-α | Hs01046818_m1 |

| ER-β, estrogen receptor-β | Hs01100358_m1 |

| GPER/GPR30, G protein-coupled ER | Hs00173506_m1 |

| TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 | Hs01042313_m1 |

| COX2, cyclooxygenase-2 | Hs00153133_m1 |

| 18S ribosomal subunit | Hs99999901_s1 |

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was performed as previously described (17). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.02% Triton X-100, and then incubated with the following primary antibodies: oligodendrocyte marker O4 mAb (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), MAP2 pAb (Millipore), GFAP mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), GnRH pAb (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and KISS1R pAb (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA) and secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCanto II instrument (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Each area of positivity was determined by gating on the same cells stained with isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies. Data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva Software (BD Pharmingen) and FlowJo v10 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Immunofluorescence

Immunocytochemistry was performed as previously described (16, 17) using the following primary antibodies: anti-GFAP mAb (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GnRH pAb (1:100, Abcam), anti-KISS1R pAb (1:100, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc.), antikisspeptin pAb (1:50, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals), anti-NF-κB pAb (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-acetylated α-tubulin mAb (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by Alexa Fluor-568 or 488 conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200, Molecular Probes). For acetylated α-tubulin/F-actin dual staining, cells were at first stained with rhodamine phalloidin (1:40, Molecular Probes). Negative controls were performed avoiding primary antibodies. Slides were imaged with a Nikon Microphot-FXA microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). To 3-dimensionally evaluate cilium size, images were acquired with a Leica SP2-AOBS confocal microscope, collected as z-stacks through a 63× 1.4NA oil-immersion objective and sampled according to the Nyquist criterion. Images were deconvolved with Huygens Professional software (SVI, Netherlands) and quantitatively analyzed using Volocity 5.2 software (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (17) using the following antibodies: anti-phospho-extracellular signal–regulated kinase (pERK)1/2 mAb (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-STAT1 pAb (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-KISS1R pAb (1:1000, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals), and anti-β-actin mAb (1:10,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Euroclone) were used for detection.

GnRH release assay

Culture media were filtered with Strata C18 columns (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), lyophilized as previously described (16) and immediately used for the GnRH quantification with the LH-RH-fluorescent immunoassay kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Electrophysiology

The patch clamp technique (both current- and voltage-clamp modes) in whole-cell configuration was used as previously described (18). Voltage-clamp protocol generation and data acquisition were controlled by using an output and an input of the analogic/digital-digital/analogic interfaces (Digidata 1200; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and Pclamp 9 software (Axon Instruments). Currents were low-pass filtered with a Bessel filter at 2 KHz. The passive properties parameters were estimated as previously described (19). The membrane conductance Gm and the cell linear capacitance Cm were used as the index of resting cell permeability and cell surface area, respectively. Gm and the transmembrane current Im were normalized to Cm to allow comparison between different cells, assuming Gm/Cm as specific conductance and Im/Cm as current density. Resting membrane potentials (RMPs) were recorded with the current-clamp mode. Voltage-independent currents flowing through canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC)–like cationic channels were measured with a voltage-clamp pulse protocol (18). The TRPC current flow was determined with the point-by-point subtraction of the leak Im recorded after the addition of the selective TRPC blocker gadolinium chloride (GdCl3, 50 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) from the Im, recorded at the beginning of the experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using Student’s t test and a one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey–Kramer post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Fetal hypothalamus is a rich source of neurons with a GnRH phenotype

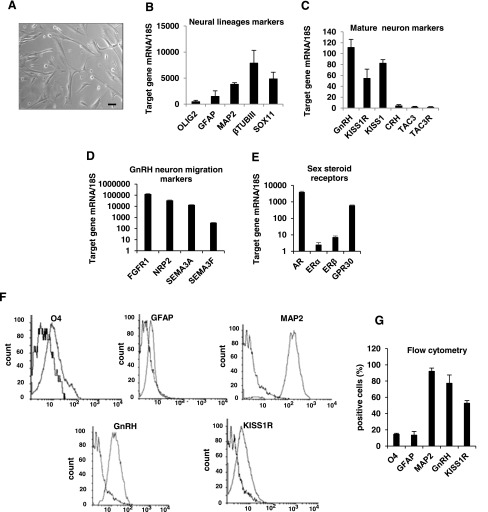

After tissue dissociation, cells were left to emerge and proliferate under standard conditions. At the first passage, adherent cells mainly showed a typical neuronal morphology with processes extending from the cell body [Fig. 1(A)]. The gene expression profile of the primary cultures was analyzed by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 1(B), hfHypo cells abundantly expressed markers of the neuronal lineage, such as β-tubulin III and MAP2, whereas glial markers specific for oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Olig2 and GFAP, respectively) were expressed at low levels. Interestingly, hfHypo cells expressed high messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of SOX11, a transcription factor known to regulate cell type-specific GnRH gene expression. Accordingly, GnRH mRNA levels were the most abundant, followed by KISS1 and KISS1R, whereas CRH, TAC3, and TAC3R transcripts were almost undetectable [Fig. 1(C)]. In addition, hfHypo cells abundantly expressed genes involved in GnRH neuron migration [Fig. 1(D)], such as FGFR1, semaphorins and their cognate receptor NRP2. Among the sex steroid receptors [Fig. 1(E)], AR and GPER1/GPR30 were the most abundant, when compared with the classical estrogen receptors (ERs; ER-α and ER-β). This gene expression profile persisted in vitro throughout the different passages (p2 through p25; not shown). To better define the specific cell fate of the primary culture, hfHypo cells were grown to confluence, and then cultured in plain medium for 3 weeks to allow spontaneous postmitotic maturation. Interestingly, mature hfHypo cells showed abundant relative expression of GnRH and KISS1R mRNA (49.9 ± 10 and 42.7 ± 3.9 arbitrary units, respectively), whereas KISS1 mRNA levels were significantly reduced compared with both the other genes (3.3 ± 0.3 arbitrary units, P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Phenotypic characterization and gene expression profile of hfHypo cells. (A) Phase contrast microphotographs showing cell morphology at passage 1 (scale bar: 50 μm). (B–E) Relative mRNA expression by qRT-PCR analysis of target genes normalized over 18S ribosomal RNA subunit, taken as the reference gene, and reported as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (F) Representative overlaid histograms for O4, GFAP, MAP2, GnRH and KISS1R markers (right peak) with their isotype controls (negative control; left peak), as detected in hfHypo cells by flow cytometric analysis; a total of 104events for each sample was acquired and the (G) bar graph shows the percentage of positive cells reported as mean ± standard error of the mean of at least 4 samples for each marker.

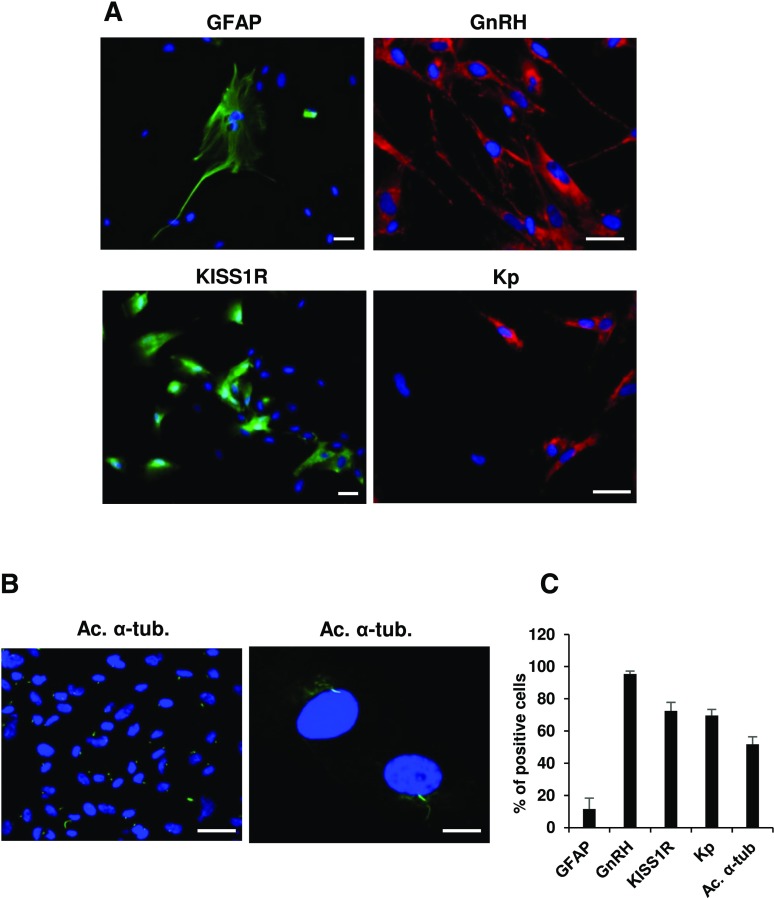

To further characterize the hfHypo cell phenotype, we evaluated the percentage of cells positive to specific markers by flow cytometry [Fig. 1(F, G)]. The majority of cells (92.02 ± 3.9%) were positive for the neuronal marker MAP2, with a low percentage of cells being positive for the glial markers GFAP (13.5 ± 4%) and O4 (14.5 ± 1%). Among the neuronal population about 80% were GnRH-positive cells (77.3 ± 10.2%) and more than 50% expressed KISS1R (52.7 ± 3.3%). Immunocytochemistry confirmed the prominent neuronal phenotype, showing very few GFAP-positive cells (11.5 ± 6.8%) and an abundant positivity for GnRH (95.4 ± 1.7%), KISS1R (72.5 ± 5.3%) and kisspeptin [69.7 ± 3.6%; Fig. 2(A, C)]. Interestingly, a high percentage of cells (more than 50%) possessed a primary cilium, stained with the specific marker acetylated α-tubulin [Fig. 2(B, C)].

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical characterization of hfHypo cell phenotype. (A) Representative images of cells expressing GFAP, GnRH, KISS1R, and kisspeptin (Kp; scale bars: 50 μm). (B) Acetylated α-tubulin (Ac. α-tub.; green) marks primary cilium on hfHypo cells, as shown by images at low (left, scale bar: 50 μm) and high (right, scale bar: 10 μm) magnification; nuclei are counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (C) Quantitative analysis of positive cells for each marker, as calculated by counting at least 5 fields from 3 different experiments. Results are expressed as percentage of positive cells over total and are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean.

hfHypo cells respond to kisspeptin and release GnRH

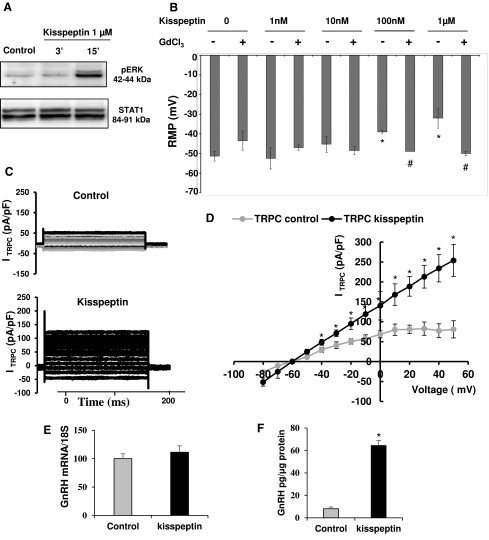

To perform a biological characterization of hfHypo cells, we analyzed their ability in responding to kisspeptin. Consistent with the known intracellular mechanism triggered via KISS1R activation (20), exposing cells to kisspeptin (1 µM) determined a phospho-ERK increase [Fig. 3(A)]. Considering that kisspeptin is able to depolarize GnRH neurons mainly through the activation of TRPC channels (21), we performed electrophysiological experiments in current-clamp conditions. The mean RMP recorded in untreated hfHypo cells was –49.4 ± 1.8 mV. None of tested cells exhibited action potential. Addition of increasing concentrations of kisspeptin (10−9 to 10−6 M) to the bath solution caused a clear depolarizing effect that reached the statistical significance with 100-nM and 1-µM doses [P < 0.05 vs control; Fig. 3(B)]. This effect was significantly prevented by the specific TRPC blocker GdCl3 [P < 0.05; Fig. 3(B)].

Figure 3.

Kisspeptin effects in hfHypo cells. (A) Western blot analysis of ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in serum-starved cells treated or not (control) with 1-µM kisspeptin for 3 or 15 minutes. STAT1 immune-detection was used as protein loading control. (B) Dose-response effect of kisspeptin on RMP in the absence (–) or presence (+) of TRPC blocker GdCl3 (*P < 0.05 vs control; #P < 0.05 vs the related kisspeptin dose alone). (C) Representative TRPC current traces from a control cell (upper) or in the presence of 1μM kisspeptin (lower); current traces result from the point-by-point subtraction of currents recorded in the absence or presence of 50-μM GdCl3. (D) I–V curves, plotting the mean cumulative data from 12 cells for each condition; currents were normalized to whole-cell capacitance (*P < 0.05 vs control). (E) GnRH mRNA expression by qRT-PCR in hfHypo cells treated or not (control) with kisspeptin (1 µM, 24 hours); data are normalized over 18S ribosomal RNA taken as the reference gene, and are reported as mean ± SEM of 4 experiments performed in triplicate. (F) GnRH secretion in the culture medium by hfHypo cells treated or not (control) with kisspeptin (1 µM, 24 hours) as detected by fluorescent immunoassay; results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 experiments performed in triplicate (*P < 0.05 vs control).

To further demonstrate the effect of kisspeptin on TRPC currents we performed electrophysiological experiments in voltage clamp conditions. TRPC currents were isolated thanks to the use of GdCl3. Kisspeptin (1 μM) clearly increased the TRPC currents amplitude in comparison with a control cell [Fig. 3(C)]. Note that the GdCl3-sensitive current is almost linear, as expected for nonselective cation channels, and significantly increased by kisspeptin addition [P < 0.05 vs control; Fig. 3(D)].

Moreover, 24-hour treatment with 1-µM kisspeptin did not change GnRH mRNA expression [Figure 3(E)], whereas it significantly increased GnRH secretion into the culture media, when compared with untreated cells [P < 0.05; Fig. 3(F)].

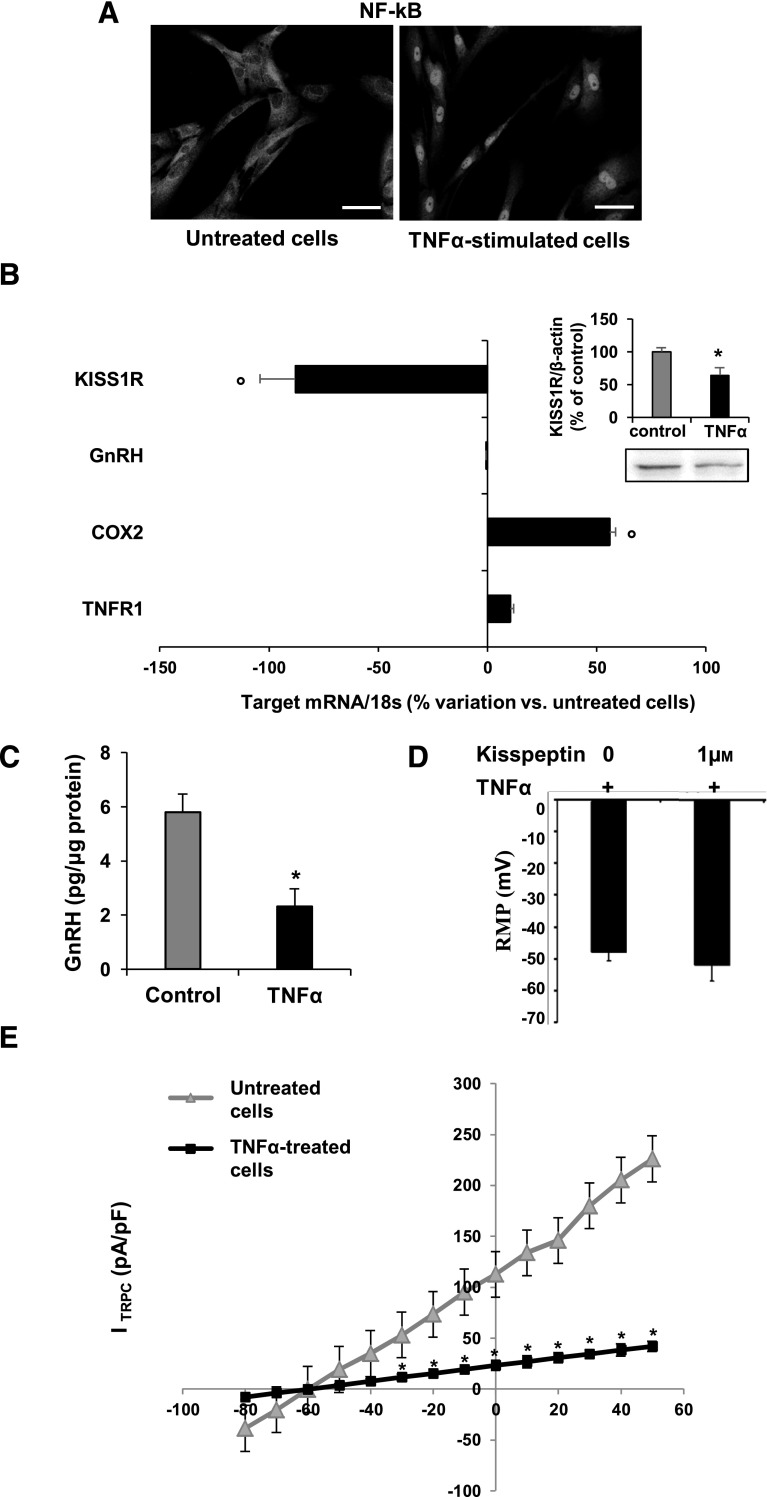

TNF-α downregulates kisspeptin signaling and GnRH release by hfHypo cells

We next wondered if hfHypo cells could be a useful tool to evaluate direct actions of insults interfering with GnRH neuron physiology. Specifically, we tested the effects of inflammation using TNF-α. We firstly verified that hfHypo cells expressed TNFR1 mRNA, the most abundant TNF-α receptor in the brain (22) and that 24-hour exposure to 10 ng/mL TNF-α did not affect cell viability (not shown). The inflammatory response of TNF-α–stimulated cells was demonstrated by immunolocalization of NF-κB p65. In untreated cells NF-κB p65 was totally inactive and retained in the cytoplasm [Fig. 4(A)]. Exposing cells to 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 5 hours induced a complete nuclear NF-κB p65 translocation [Fig. 4(A)]. Accordingly, prolonged exposure to TNF-α (24 hours) activated NF-κB p65 target gene transcription determining a significant increase of COX2 mRNA [P < 0.001 vs control; Fig. 4(B)]. Interestingly, TNF-α significantly downregulated both mRNA (P < 0.001 vs. control) and protein (P < 0.05 vs. control) expression of KISS1R [Fig. 4(B)]. Moreover, despite no effects on GnRH gene expression [Fig. 4(B)], basal secretion of GnRH was significantly reduced by TNF-α treatment [P < 0.05; Fig. 4(C)].

Figure 4.

TNF-α activates proinflammatory pathways and inhibits kisspeptin signaling in hfHypo cells. (A) Immunocytochemical detection of NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation in TNF-α–stimulated (10 ng/mL for 5 hours) compared with untreated (control) cells (scale bar: 50 μm). (B) qRT-PCR analysis showing the percentage variation of KISS1R, GnRH, COX2, and TNFR1 mRNA expression in TNF-α–treated (10 ng/mL for 24 hours) vs control cells; data are normalized over 18S ribosomal RNA subunit and results are reported as mean ± SEM of 4 separate experiments performed in triplicate (°P < 0.001 vs control); inset: representative immunoblot of KISS1R protein expression and computer-assisted quantification of band intensity for control and TNF-α–treated (10 ng/mL for 24 hours) cells; data are normalized over β-actin and are expressed as percentage of control; results are reported as mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate (*P < 0.05 vs control). (C) GnRH secretion by control and TNF-α–treated (10 ng/mL for 24 hours), cells as detected by fluorescent immunoassay; results are reported as mean ± SEM of 4 experiments performed in triplicate (*P < 0.05 vs control). (D) RMP measured in mV from TNF-α–pretreated cells (+10 ng/mL for 24 hours) in the absence (0) or presence of kisspeptin (1 μm). (E) Kisspeptin-sensitive TRPC currents, ITRPC (pA/pF), as evaluated from control (triangle) or TNF-α–treated cells (square). *P < 0.05 vs control, n = 8.

We next tested whether TNF-α affected the hfHypo cell electrophysiological response to kisspeptin. As reported in Figure 4(D), when cells were pretreated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL, 24 hour), 1µM kisspeptin did not cause any significant change in RMP. Accordingly, patch clamp recordings revealed that TNF-α treatment significantly hampered kisspeptin-sensitive TRPC currents [P < 0.05; Fig. 4(E)].

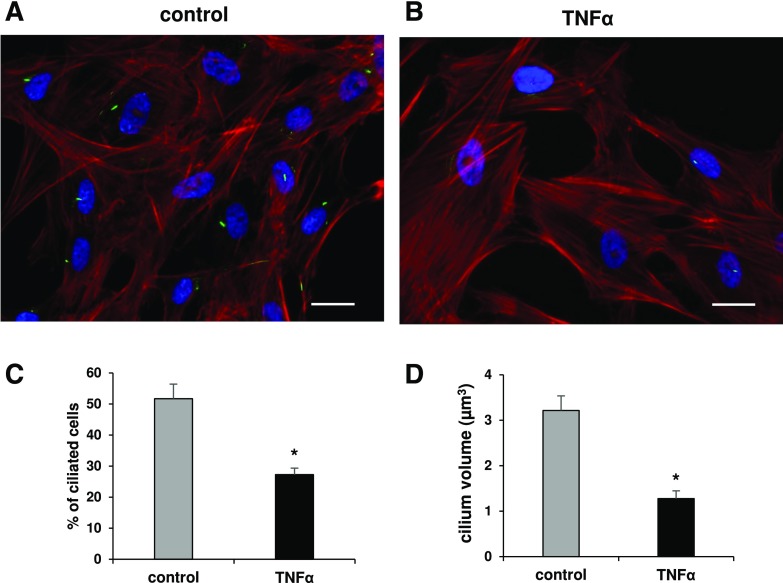

Because hfHypo cells possessed a primary cilium we examined whether TNF-α affected ciliogenesis. As shown in Figure 5, TNF-α exposure determined a significant reduction in the percentage of cells exhibiting a primary cilium (27.3 ± 2%), when compared with control cells [51.7 ± 5%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 5(A–C)]. The primary cilium volume was also significantly reduced in TNF-α–treated cells [P < 0.0001; Fig. 5(D)].

Figure 5.

TNF-α inhibits primary cilia expression in hfHypo cells. (A, B) Merge representative images of acetylated α-tubulin (green)/F-actin (red) dual immunostaining showing the primary cilium formation in untreated [control (A)] or TNF-α–treated [10 ng/mL for 24 hours (B)]) cells (scale bar: 25 µm). (C) Number of ciliated cells, counted in 4 different random fields for each condition and expressed as percentage of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained (blue) total cells; results are reported as the mean ± SEM of 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.0001 vs control). (D) Computer-assisted evaluation of the primary cilium volume performed in at least 12 cells for each condition and reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.0001 vs control.

Discussion

In humans, the study of GnRH neuron physiology in vivo is extremely difficult given their low number and distribution as a diffuse network within the adult hypothalamus. The development of immortalized GnRH neuron cell lines (13–15) doubtless facilitated in vitro studies. However, besides limitations inherent to the immortalization procedure, which could alter normal neuron biology, to date available lines are invariably of mouse (GT1-7, GN11) or rat (GnV-3) origin. In this study, we report for the first time the isolation and characterization of primary cultures of hypothalamic GnRH neurons of human origin. This in vitro approach bears some limitations due to the fact that primary cultures may contain different cell types reflecting the source tissue heterogeneity, and therefore including not only neurons but also glial cells. However, the first positive result of our study was that hfHypo cells presented a clearly neuronal phenotype and were characterized by a high percentage of GnRH-positive cells (80%). In addition, the hfHypo cell identity as GnRH neurons was documented by the ability to release GnRH in the culture medium, express KISS1R, and thereby respond to kisspeptin, the main physiological stimulus for GnRH neurons (5). Interestingly, all these features persisted long-term throughout several passages (p2 to p25) and were observed without any prior cell-culture purification or cell-sorting procedure, thus indicating that human fetal hypothalamus, at least as of week 12 of gestation, may be regarded as a rich source of neurons with a GnRH-secreting phenotype.

Gene expression data corroborated the GnRH neuronal phenotype of hfHypo cells, which, besides GnRH and KISS1R, also abundantly express FGFR1, NRP2, SEMA3A, and SEMA3F, essential for the migratory processes during embryogenesis (23). In contrast, CRH expression, which is specific of neurons located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, anatomically distinct from the regions occupied by the GnRH neurons, was almost undetectable, thus confirming the accuracy of the fetal tissue sampling. Similarly, we have found an almost absent expression of both TAC3/neurokinin B and TAC3R genes, thereby confirming the lack of the expression of this system in GnRH neurons in the human, as previously reported in other animal species (24, 25). Indeed, it has been shown that the neurokinin B is released by a distinct group of kisspeptin, non-GnRH neurons, which act by an autocrine or paracrine mechanism to enhance kisspeptin secretion (26).

The expression of KISS1 by GnRH neurons is a controversial issue, with most studies carried out in the rat, having identified KISS1 neurons as a neuronal population distinct from GnRH neurons (5). However, our observation that hfHypo cells express KISS1 is in agreement with data reported in other animal species, such as sheep (27) and mice (28), thus indicating, for the first time in a human model, a possible autocrine/paracrine regulation of GnRH release by kisspeptin. Accordingly, human fetal GnRH-secreting neurons (FNCB4) isolated from the olfactory epithelium (2) also express KISS1 (16). Given the fetal origin of these cells and our observation that KISS1 expression is lost by hfHypo cells when left to differentiate in vitro, we may speculate that this function could be specific of fetal life. Guimiot et al. (29) recently reported that kisspeptin expression increased from 15 weeks to midgestation at the tuberal hypothalamus of human fetuses and then decreased until disappearing at term gestation, whereas GnRH positivity persisted. Overall, these findings suggest a specific role for kisspeptin in the early gestational period and may limit the significance of our cellular model in elucidating GnRH physiology in adult as opposed to fetal life. Further studies are needed to definitely clarify this issue. In particular, it would be of considerable interest compare the phenotype of the premigration FNCB4 neurons, with that of the postmigration hfHypo neurons to add new information about the developmental processes of human GnRH neurons.

Gene expression analysis revealed that hfHypo cells also express classical sex steroids receptors, with AR being the most abundant in comparison with both ER-α and ER-β. The low ER levels are in agreement with the prevalent hypothesis that the influence of estrogen on GnRH is not direct but is conveyed to GnRH neurons via interneurons such as kisspeptin neurons, as consistently reported in animal models (30). At variance, the membrane estrogen receptor GPER1/GPR30, which has been recently implicated in rapid action of estrogen in GnRH neurons (31), is expressed at high levels by hfHypo cells. Exploring the role played by GPER1/GPR30 in hfHypo cells could help in understanding the mechanisms underlying direct and rapid estrogenic action on human GnRH neurons.

Interestingly, hfHypo cells express a high abundance of SOX11 transcript, further corroborating their phenotype as GnRH neurons under development. It is known that a SOX11 expression pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that this gene is important in the developing nervous system (32) and plays a role in the specific activation of GnRH gene transcription in a limited population of hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons (33). In fact, SOX11 is found in susbstantially lower abundance in non-GnRH hypothalamic cells (33).

Our study also documents for the first time the deleterious direct effect of inflammation on the responsiveness of GnRH neurons to kisspeptin. Inflammation is a hallmark of age-related diseases, including MetS. An association between metabolic dysfunctions and alterations of the reproductive axis has emerged from several epidemiological and clinical studies (12). The pathogenic mechanism underlying this association has not yet been completely understood, but dietary-induced hypothalamic inflammation, most likely affecting GnRH neuron function, may play a causative role. Accordingly, molecular inflammation within the hypothalamus caused the inhibition of GnRH gene expression by activated microglia via a TNF-α–induced Ikβ kinase (IKK-β)/NF-κB pathway (34). Recent studies demonstrated that HFD-induced MetS in rabbits impaired GnRH neurons, with a reduction of circulating gonadotropins and sex hormones related to MetS severity (11). In this animal model, HFD-induced inflammatory injury at the hypothalamic level was associated with a substantially decreased KISS1R positivity (11). This finding is consistent with the direct inhibitory effect of TNF-α on KISS1R expression we observed in hfHypo cells. Furthermore, it supports the idea that the deleterious effects of inflammation on GnRH neurons function, activated by metabolic disturbances, are exerted through a reduced responsiveness to kisspeptin due to a downregulation of its receptor. Undoubtedly, direct exposure of hfHypo cells to TNF-α was able to decrease not only the GnRH release but also the capability of kisspeptin to elicit membrane electrical properties as expected by KISS1R activation (20).

Interestingly, we also report for the first time that inflammation triggers the loss of primary cilium expression in human GnRH neurons. The primary cilium is a typically solitary, nonmotile appendage that projects from the cell surface of several cell types, including neurons. These antenna-like sensory organelles are able to survey the extracellular milieu and transmit signals into the cell (35). Indeed, certain G protein-coupled receptors selectively localize to neuronal cilia (35) and murine GnRH neurons possess primary cilia, which are enriched for KISS1R (36). Hence, it is conceivable that impairment of ciliogenesis may interfere with kisspeptin signaling in GnRH neurons. The loss of primary cilia by TNF-α treatment has been demonstrated in mesenchymal stromal cells (37). We here report that TNF-α exposure reduced by half (27 vs 50%) the percentage of ciliated hfHypo cells, which also showed a reduction of cilia volume, indicative of an impaired formation process. Although we did not perform time-course experiments, based on cilia volume data, it is conceivable that the effect on ciliogenesis could be worsened by prolonged TNF-α exposure further reducing the percentage of ciliated cells. The TNF-α–mediated inhibition of ciliogenesis in hfHypo cells could be responsible for the reduced electrophysiological response to kisspeptin. Accordingly, disruption of cilia selectively on GnRH neurons in the mouse led to a reduction of kisspeptin-mediated GnRH neuron firing rate, even though this effect was substantial in male but not in female animals (36). Our findings, obtained in GnRH neurons from both female and male fetuses, did not evidence the gender differences highlighted in the mouse model. However, it should be taken into account that besides cilia formation, TNF-α strongly reduced KISS1R expression in hfHypo cells, and therefore, the combination of the 2 effects could impair KISS1R signaling rather than ciliogenesis alone. Koemeter-Cox et al. (36) also reported that although cilia on GnRH neurons enhance KISS1R signaling, they are not required for sexual maturation nor adult reproductive function in mice. In humans, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is a feature of the Bardet–Biedl syndrome ciliopathy (38). A better comprehension of the mechanisms linking ciliopathies to reproductive axis deficit may clarify the functional significance of TNF-α–impaired ciliogenesis in human GnRH neurons.

In conclusion, our study reports that fetal hypothalamus is a rich source of neurons with a GnRH phenotype, able to respond to kisspeptin and release GnRH. Moreover, hfHypo cells retain their phenotype in vitro, most likely due to their fetal origin, and may be regarded as a new powerful tool for investigations on human GnRH neuron biology, particularly to unravel the direct action of metabolic factors. Among these factors, we here explored the role of inflammatory cytokines, showing that TNF-α may impair not only the GnRH neurons secretory activity but also their ability in responding to kisspeptin through different mechanisms (KISS1R expression downregulation and primary cilia loss), overall leading to KISS1R signaling reduction.

Finally, given the fetal origin of hfHypo cells, our results are also of importance when considering the detrimental effects that maternal inflammation during pregnancy may have on fetal development, causing long-term consequences, according to “the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis” (39). In this regard, a recent study demonstrated that prenatal maternal exposure to inflammatory insult impaired the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis in rat offspring (40).

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GnRH

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- hfHypo

- human fetal hypothalamic

- KISS1R

- kisspeptin receptor

- MetS

- metabolic syndrome

- mRNA

- messenger RNA

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- RMP

- resting membrane potential

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor α

- TRPC

- canonical transient receptor potential.

References

- 1.Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Jorgenson KL, Bergen HT, Weesner GD, Pfaff DW. Biology of normal luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons during and after their migration from olfactory placode. Endocr Rev. 1992;13(4):623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vannelli GB, Ensoli F, Zonefrati R, Kubota Y, Arcangeli A, Becchetti A, Camici G, Barni T, Thiele CJ, Balboni GC. Neuroblast long-term cell cultures from human fetal olfactory epithelium respond to odors. J Neurosci. 1995;15(6):4382–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch B, Gaillard RC, Culler MD, Negro-Vilar A. Immunohistochemical detection of proluteinizing hormone-releasing hormone peptides in neurons in the human hypothalamus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74(1):135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrabovsky E, Liposits Z. Afferent neuronal control of type-I gonadotropin releasing hormone neurons in the human. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinilla L, Aguilar E, Dieguez C, Millar RP, Tena-Sempere M. Kisspeptins and reproduction: physiological roles and regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(3):1235–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oakley AE, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Kisspeptin signaling in the brain. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(6):713–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herde MK, Geist K, Campbell RE, Herbison AE. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons extend complex highly branched dendritic trees outside the blood-brain barrier. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3832–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teerds KJ, de Rooij DG, Keijer J. Functional relationship between obesity and male reproduction: from humans to animal models. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(5):667–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2111–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, Nguyen HT, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Wisse BE, Morton GJ, Horvath TL, Baskin DG, Tschöp MH, Schwartz MWJ. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morelli A, Sarchielli E, Comeglio P, Filippi S, Vignozzi L, Marini M, Rastrelli G, Maneschi E, Cellai I, Persani L, Adorini L, Vannelli GB, Maggi M. Metabolic syndrome induces inflammation and impairs gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus in rabbits. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382(1):107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Forti G, Maggi M. Update in testosterone therapy for men. J Sex Med. 2011;8(3):639–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellon PL, Windle JJ, Goldsmith PC, Padula CA, Roberts JL, Weiner RI. Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron. 1990;5(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radovick S, Wray S, Lee E, Nicols DK, Nakayama Y, Weintraub BD, Westphal H, Cutler GB Jr, Wondisford FE. Migratory arrest of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(8):3402–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansuy V, Geller S, Rey JP, Campagne C, Boccard J, Poulain P, Prevot V, Pralong FP. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of proliferating and differentiated GnRH-expressing GnV-3 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;332(1–2):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morelli A, Marini M, Mancina R, Luconi M, Vignozzi L, Fibbi B, Filippi S, Pezzatini A, Forti G, Vannelli GB, Maggi M. Sex steroids and leptin regulate the “first kiss” (KiSS 1/G-protein-coupled receptor 54 system) in human gonadotropin-releasing-hormone-secreting neuroblasts. J Sex Med. 2008;5(5):1097–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarchielli E, Marini M, Ambrosini S, Peri A, Mazzanti B, Pinzani P, Barletta E, Ballerini L, Paternostro F, Paganini M, Porfirio B, Morelli A, Gallina P, Vannelli GB. Multifaceted roles of BDNF and FGF2 in human striatal primordium development: an in vitro study. Exp Neurol. 2014;257:130–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sassoli C, Chellini F, Squecco R, Tani A, Idrizaj E, Nosi D, Giannelli M, Zecchi-Orlandini S. Low intensity 635 nm diode laser irradiation inhibits fibroblast-myofibroblast transition reducing TRPC1 channel expression/activity: new perspectives for tissue fibrosis treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48(3):318–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Franco A, Guasti D, Squecco R, Mazzanti B, Rossi F, Idrizaj E, Gallego-Escuredo JM, Villarroya F, Bani D, Forti G, Vannelli GB, Luconi M. Searching for classical brown fat in humans: development of a novel human fetal brown stem cell model. Stem Cells. 2016;34(6):1679–1691 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, Brézillon S, Tyldesley R, Suarez-Huerta N, Vandeput F, Blanpain C, Schiffmann SN, Vassart G, Parmentier M. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(37):34631–34636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C, Roepke TA, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. Kisspeptin depolarizes gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through activation of TRPC-like cationic channels. J Neurosci. 2008;28(17):4423–4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadeau S, Rivest S. Effects of circulating tumor necrosis factor on the neuronal activity and expression of the genes encoding the tumor necrosis factor receptors (p55 and p75) in the rat brain: a view from the blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience. 1999;93(4):1449–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cariboni A, Hickok J, Rakic S, Andrews W, Maggi R, Tischkau S, Parnavelas JG. Neuropilins and their ligands are important in the migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2387–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amstalden M, Coolen LM, Hemmerle AM, Billings HJ, Connors JM, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Neurokinin 3 receptor immunoreactivity in the septal region, preoptic area and hypothalamus of the female sheep: colocalisation in neurokinin B cells of the arcuate nucleus but not in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Wu M, García-Galiano D, Hobbs SJ, Bosch MA, Pinilla L, Clifton DK, Dearth A, Ronnekleiv OK, Braun RE, Palmiter RD, Tena-Sempere M, Alreja M, Steiner RA. Regulation of NKB pathways and their roles in the control of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152(11):4265–4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young J, George JT, Tello JA, Francou B, Bouligand J, Guiochon-Mantel A, Brailly-Tabard S, Anderson RA, Millar RP. Kisspeptin restores pulsatile LH secretion in patients with neurokinin B signaling deficiencies: physiological, pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Neuroendocrinology. 2013; 97(2):193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pompolo S, Pereira A, Estrada KM, Clarke IJ. Colocalization of kisspeptin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ovine brain. Endocrinology. 2006;147(2):804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terasaka T, Otsuka F, Tsukamoto N, Nakamura E, Inagaki K, Toma K, Ogura-Ochi K, Glidewell-Kenney C, Lawson MA, Makino H. Mutual interaction of kisspeptin, estrogen and bone morphogenetic protein-4 activity in GnRH regulation by GT1-7 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;381(1–2):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guimiot F, Chevrier L, Dreux S, Chevenne D, Caraty A, Delezoide AL, de Roux N. Negative fetal FSH/LH regulation in late pregnancy is associated with declined kisspeptin/KISS1R expression in the tuberal hypothalamus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):E2221–E2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terasawa E, Kenealy BP. Neuroestrogen, rapid action of estradiol, and GnRH neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(4):364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noel SD, Keen KL, Baumann DI, Filardo EJ, Terasawa E. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) in rapid action of estrogen in primate LHRH neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(3):349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jay P, Gozé C, Marsollier C, Taviaux S, Hardelin JP, Koopman P, Berta P. The human SOX11 gene: cloning, chromosomal assignment and tissue expression. Genomics. 1995;29(2):541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HD, Choe HK, Chung S, Kim M, Seong JY, Son GH, Kim K. Class-C SOX transcription factors control GnRH gene expression via the intronic transcriptional enhancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2011; 25(7):1184–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang G, Li J, Purkayastha S, Tang Y, Zhang H, Yin Y, Li B, Liu G, Cai D. Hypothalamic programming of systemic ageing involving IKK-β, NF-κB and GnRH. Nature. 2013; 497(7448):211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green JA, Mykytyn K. Neuronal ciliary signaling in homeostasis and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010; 67(19):3287–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koemeter-Cox AI, Sherwood TW, Green JA, Steiner RA, Berbari NF, Yoder BK, Kauffman AS, Monsma PC, Brown A, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K. Primary cilia enhance kisspeptin receptor signaling on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014; 111(28):10335–10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vézina A, Vaillancourt-Jean E, Albarao S, Annabi B. Mesenchymal stromal cell ciliogenesis is abrogated in response to tumor necrosis factor-α and requires NF-κB signaling. Cancer Lett. 2014; 345(1):100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsythe E, Beales PL. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013; 21(1):8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segovia SA, Vickers MH, Gray C, Reynolds CM. Maternal obesity, inflammation, and developmental programming. Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014:418975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izvolskaia MS, Tillet Y, Sharova VS, Voronova SN, Zakharova LA. Disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in rat offspring following prenatal maternal exposure to lipopolysaccharide. Stress. 2016; 19(2):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]