Abstract

Background & Aims

Celiac disease (CeD) provides an opportunity to study autoimmunity and the transition in immune cells as dietary gluten induces small intestinal lesions.

Methods

Seventy-three celiac disease patients on a long-term, gluten-free diet ingested a known amount of gluten daily for 6 weeks. A peripheral blood sample and intestinal biopsy specimens were taken before and 6 weeks after initiating the gluten challenge. Biopsy results were reported on a continuous numeric scale that measured the villus-height–to–crypt-depth ratio to quantify gluten-induced intestinal injury. Pooled B and T cells were isolated from whole blood, and RNA was analyzed by DNA microarray looking for changes in peripheral B- and T-cell gene expression that correlated with changes in villus height to crypt depth, as patients maintained a relatively healthy intestinal mucosa or deteriorated in the face of a gluten challenge.

Results

Gluten-dependent intestinal damage from baseline to 6 weeks varied widely across all patients, ranging from no change to extensive damage. Genes differentially expressed in B cells correlated strongly with the extent of intestinal damage. A relative increase in B-cell gene expression correlated with a lack of sensitivity to gluten whereas their relative decrease correlated with gluten-induced mucosal injury. A core B-cell gene module, representing a subset of B-cell genes analyzed, accounted for the correlation with intestinal injury.

Conclusions

Genes comprising the core B-cell module showed a net increase in expression from baseline to 6 weeks in patients with little to no intestinal damage, suggesting that these individuals may have mounted a B-cell immune response to maintain mucosal homeostasis and circumvent inflammation. DNA microarray data were deposited at the GEO repository (accession number: GSE87629; available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Keywords: Oral Tolerance, Mucosal Immunity, Autoimmunity, Regulatory B Cell

Abbreviations used in this paper: Cd, crypt depth; CeD, celiac disease; cRNA, complementary RNA; TG2, transglutaminase 2; TR, T-cell receptor; Vh, villus height; Vh:Cd, ratio of villus height to crypt depth

Graphical abstract

Summary.

A gluten challenge in celiac patients provides a unique opportunity to study the immunology associated with the transition from relative health to autoimmunity. This study showed that a B-cell population in peripheral blood correlated inversely with gluten-dependent small intestinal lesions, implicating a protective mechanism.

Human beings ingest a wide variety of food proteins in the diet that are considered foreign with respect to the immune system. Immune cells in the small intestine survey the contents in the intestinal environment looking for pathogens. Oral tolerance is a mechanism that balances the need to promote tolerance to orally administered, foreign, yet harmless, food proteins with the need to provide a host defense against harmful pathogens in the intestine.1 Although not well understood, oral tolerance to a food protein is an active immune response whose function is to suppress inflammatory immune responses to the same food protein when presented to the immune system for a second time. In celiac disease (CeD), a lack of oral tolerance develops to a family of cereal proteins collectively referred to as gluten,2 resulting in a pathogenic and inflammatory immune response.

The small intestinal mucosa consists of an epithelium and its underlying structures, which are immediately adjacent to the intestinal lumen and in contact with digested food. To increase surface area for nutrient absorption, the mucosa projects finger-like extensions called villi into the lumen of the gut. At the base of the villi are proliferative crypts. In patients with CeD, gluten ingestion results in blunting of the villi and hypertrophy or elongation of the crypts. The ratio of the height of the villi (Vh) to the depth of the crypt (Cd), expressed as Vh:Cd, has been used to quantify the extent of intestinal damage in CeD.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 In severe cases, villi shrink completely with extensive crypt elongation, resulting in a flat mucosa and a Vh:Cd measurement approaching zero.

HLA-DQ is an important genetic factor that predisposes individuals to CeD and type 1 diabetes.9, 10 A total of 5%–10% of individuals with type 1 diabetes develop CeD,11 which is significantly higher than the chance of developing CeD in the overall Caucasian population, estimated to be 1%.12 Most CeD patients (90%) express HLA-DQ2.5, whereas the remainder express HLA-DQ2.2 or HLA-DQ8.13 Gluten peptides that are deamidated by the self-protein transglutaminase 2 (TG2) bind strongly to HLA-DQ and the resulting complex is presented to HLA-DQ–restricted CD4+ T cells,14 resulting in a T-cell response to deamidated gluten.15 In addition to the T-cell response, gluten-dependent, disease-specific B cells appear early during disease pathogenesis. They precede gut damage, often are predictive of impending disease,16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and produce antibodies specific for deamidated gluten and TG2.21 It is unclear whether gluten-dependent auto-antibodies against TG2 contribute to the disease and there is little evidence that T cells with specificity for self-antigens drive the disease.

The B cell recognizes a specific protein antigen, such as gluten or TG2, through direct interactions with its B-cell receptor containing a membrane-bound immunoglobulin.22 The immunoglobulin determines antigen specificity and is unique for each B-cell clone. B-cell receptor signaling contributes strongly to B-cell proliferation and differentiation. B cells can be antigen-presenting cells23 and have the ability to express HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8. Because gluten peptides are excellent substrates for TG2 and the two proteins form a transient covalent complex, the possibility exists that a deamidated gluten- or TG2-specific B cell binds the complex through the B-cell receptor, internalizes, and then presents gluten on HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 at the B cell surface to a gluten-specific HLA-DQ2– or HLA-DQ8–restricted CD4+ T cell.15, 24 In this scenario, the resulting B cell is a functional antigen-presenting cell whose cell phenotype, as determined by B-cell–receptor signaling and direct B- and T-cell co-stimulatory interactions, ultimately may be under the control of gluten.

An inflammatory, gluten-induced immune response in the gut may propagate systemically in peripheral blood. The plausible trafficking of B and T cells and anti-TG2 to sites beyond the gut may help to explain several systemic clinical manifestations of CeD,25 including dermatitis herpetiformis, a gluten-dependent blistering skin condition. CeD also may manifest as a bone disease,26 in the central nervous system as ataxia and brain atrophy,27 or as an isolated subclinical28 or severe liver disease.29 Evidence indicates that immune cells migrate to and from the gut in peripheral blood. For example, disease-specific T cells expressing the gut-homing β7 integrin migrate transiently to the periphery upon gluten challenge in CeD patients; these T cells are inflammatory in nature.30, 31 The peripheral blood therefore may be a good source to obtain biomarkers of the disease.

It is not clear how gluten interacts with mechanisms of peripheral immune tolerance and whether B or T cells are responsible for disrupting the tolerogenic environment of the small intestine. The objective of this work was to determine if peripheral blood B and T cells modify gene expression in response to a 6-week gluten challenge in patients with treated CeD, and to correlate any changes in peripheral B- or T-cell gene expression with the extent of gluten-induced histological damage to the small intestine.

Materials and Methods

All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Human Clinical Study

Intestinal biopsy specimens and whole blood samples were collected from a single clinical site at the University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland, with patient consent (ethics approval ETL R09084M, ETL R10135M, and Eudra CTs 2009-012221-10 and 2010-023127-23). For each time point, small-bowel biopsy specimens (4–7 specimens) were sampled from the descending duodenum, sectioned, and scored by the same evaluator using standardized morphometric tools.5, 32 Of the 73 patients included in this analysis, 37% were male and 63% were female. The age range was 23–74 years with a median age of 59 years. For 6 weeks, patients ingested 6 g/day (20 patients), 3 g/day (26 patients), or 1.5 g/day (27 patients) wheat gluten with a meal. At the baseline time point, patients (85%) were negative for antibodies against transglutaminase 2. All patients completed the full 6-week study.

B- and T-Cell Isolation

CD19+ B cells and CD3+ T cells were purified together from freshly prepared, venous whole blood (14 mL) using whole-blood CD19 and CD3 magnetic microbeads and the whole-blood column kit as specified by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). EDTA was used as a blood anticoagulant. The final cell pellet containing purified B and T cells was resuspended in TRIzol (Fisher Scientific) reagent (5 mL) to lyse the cells and protect the RNA from degradation. The denatured B- and T-cell lysate was stored at -70°C for up to 3 months before purification of total RNA. For convenience, whole-blood samples may be stored on ice for up to 1 hour before adding magnetic beads. Preparation time from the point of adding magnetic beads to freezing the B- and T-cell lysate was less than 2 hours.

Total RNA Preparation

Pooled B- and T-cell lysates (5 mL) denatured in TRIzol were extracted with chloroform (0.2 vol) and the crude RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with the addition of isopropanol (0.7 vol). The RNA pellet was purified further using the RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen, Hilden Germany) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Purified total RNA was eluted from the spin column with the addition of 2 aliquots (35 μL) RNase-free water. An Agilent BioAnalyzer (Santa Clara, CA) was used to determine total RNA yield (median, 2.2 μg), purity (median A260/A280, 2.1), and size (median RNA integrity number, 9.5) for all 146 samples. Purified total RNA was stored at less than -60°C.

Microarrays

RNA samples were converted into labeled target complementary RNA (cRNA) using the Illumina TotalPrep-96 RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Briefly, 100 ng of total RNA was converted to double-stranded complementary DNA using an oligo-d(T) primer-adaptor. This complementary DNA was purified using magnetic beads and used as a template for in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase and biotin–uridine triphosphate. The resulting biotinylated cRNA was purified using magnetic beads and quantified by spectrophotometry. For hybridization, 750 ng of purified biotinylated cRNA was added to Hybridization Cocktail Buffer (Illumina), applied to arrays, and incubated at 58°C for 16 hours. After hybridization, arrays were washed and stained using standard Illumina procedures before scanning on an Illumina iScan instrument using the DirectHyb Tiff setting. Scanned images were processed by the Gene Expression module of GenomeStudio (v 1.6; Illumina) using default parameters without normalization.

A total of 146 RNA samples were analyzed by microarray representing 73 patients with high-quality microarray data at baseline and 6-week time points (146 arrays). The 146 arrays included 39 from HT-12 version 3 and 107 from HT-12 version 4 (Illumina). The version 3 arrays were discontinued by the manufacturer, requiring the change to version 4. Only probes having identical sequence content between versions were retained. Potential artifacts caused by the 2 array versions and batch were removed by assuming the batch medians for a given probe were equal (covariates were not associated with batch). This was facilitated by the fact that both baseline and 6-week time points for 60 of 73 patients (82%) were analyzed on the same batch. After median shifting each probe relative to batch medians, probe quantile normalization was performed across all samples. Background then was subtracted with a monotonic transform of probe values below background to the (0,1) interval so that all normalized probes had positive values before log transformation. After normalization, batch adjustment, and background subtraction, the difference in expression between baseline and the 6-week time points was calculated as log2 (6-wk/baseline) for each subject resulting in a matrix of 20,624 features and 73 samples.

Gene Lists

According to Bindea et al,33 genes highly enriched in T cells were segregated into immune subpopulations: T cell, T CD8, T γδ, T helper, T helper 1, T helper 2, T helper 17, T central memory, T effector memory, T follicular helper, and T regulatory. These categories were taken verbatim from the publication as multiple lists representing T-cell subpopulations and used separately to analyze the CeD data set. The T-regulatory category was characterized by one gene (FOXP3), which was not present on the Illumina array and therefore dropped from the analysis. According to Newman et al,34 genes highly enriched in T cells also were segregated into immune subpopulations: CD8, CD4 naive, CD4 memory resting, CD4 memory activated, T follicular helper, T regulatory, and T γδ. In this case, genes representing T-cell subpopulations were consolidated into one gene list. Genes highly enriched in B cells were taken verbatim from the publication as a single list (Bindea et al33) or the B-cell subpopulations were consolidated into a single list (Newman et al34). Bindea et al33 also provided gene lists representing a diverse set of immune cell expression phenotypes, including mast, natural killer, neutrophils, macrophage, eosinophils, dendritic, and cytotoxic cells, as well as SW480 cancer cells and normal mucosa, which were included as controls. The University of North Carolina IgG gene list was used previously as a predictor in breast cancer.35 All gene lists used to analyze the CeD data set are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

In whole blood, the estimate is that T cells vastly outnumber B cells. In addition, the purified CD19+ B-cell population used in this study should have little to no fully differentiated CD19- plasma B cells, further reducing the number of B cells. Given that B and T cells were purified together, B- and T-cell genes were selected from Newman et al34 based on the following characteristic: highly enriched in at least one B- or T-cell subpopulation relative to other leukocytes. In addition, for B-cell gene selection, the gene had to show little to no expression in T cells or expression that greatly exceeded that in T cells because the contribution of B cells to the overall pool of total RNA was relatively small.

Genes obtained from the Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) array platform (Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 studies) that were not expressed in the CeD data set or not present on the Illumina array platform were excluded from analysis. There were compatibility issues with T-cell receptor (TR) gene segments between array platforms. The T-cell gene list obtained from Newman et al34 was modified to retain TR transcripts by deleting Affymetrix TR probes and substituting all TR probes on the Illumina array if these probes were expressed in the CeD data set. It was common for genes obtained from Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 to correspond to multiple Illumina DNA microarray probes. All relevant probes were included in the analysis.

Correlation Between Gene Lists and ΔVh:Cd

Approximately one third of genes mapped to more than one microarray probe. In these cases, we took two different approaches. First, the gene was consolidated to a single probe by taking only the probe with the greatest SD of expression across the 73 patients. The rationale behind this approach is that probes that perform poorly show a nearly constant, low level of signal across the data set, and thus can be screened out by their low variation. This approach was referred to as genes. Second, the gene was analyzed using all corresponding probes, as opposed to the one with highest variation. This approach was referred to as probes. In both cases, expression levels for all genes or probes in a given list were averaged on log signal values, and the average expression profile across 73 patients was correlated to ΔVh:Cd using Spearman rank correlation. Nearly identical results were obtained using the median rather than the mean expression profiles for both genes and probes (data not shown) to collapse a given gene list. For determination of the core B-cell gene module, expression levels for single probes also were correlated to ΔVh:Cd using Spearman rank correlation.

Statistical Analyses

Spearman correlations were calculated in R using the standard cor.test routine. The significance of the correlation was assessed using the Student t distribution by setting exact = FALSE. The GSA module in R was used for file parsing. The Student t test used for correlations with anti-TG2 also was performed in R. Chi-squared analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA).

Celiac Disease Serum Antibodies

Serum antibodies directed against TG2-IgA were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quanta Lite h-TG-IGA; Inova Diagnostics, San Diego, CA).32 The positive threshold was 20 intensity units.

Results

Gluten-Dependent Intestinal Damage

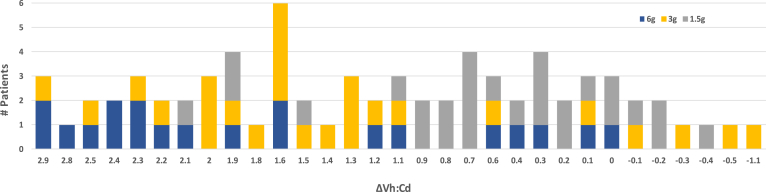

The data set consisted of 73 CeD patients following a strict gluten-free diet for at least one year. Each patient ingested 6, 3, or 1.5 g wheat gluten daily for 6 weeks. A whole blood sample, which was used to purify B and T cells, and intestinal biopsy specimens were taken before (baseline) and 6 weeks after initiating the gluten challenge. The median Vh:Cd at baseline was 2.7 (see Table 1 for patient data). Net change in intestinal biopsy from baseline to 6 weeks, defined as ΔVh:Cd, showed wide variation across all patients from no change or slight improvement to extensive mucosal damage (Figure 1). The largest ΔVh:Cd (-2.9) was observed in 3 patients who transitioned from a relatively healthy mucosa (Vh:Cd, 3.1) to a nearly flat mucosa (Vh:Cd, 0.2) in 6 weeks. Daily gluten dose for 2 of these patients was 6 g (roughly 2 slices of wheat bread). Although the 6 g gluten dose in these 2 patients resulted in extensive mucosal damage, in other patients it resulted in no damage (Figure 1, blue bars). Similar observations were made for the other 2 gluten doses, 3 g (yellow) and 1.5 g (grey). As a result, gluten dose was distributed across the full spectrum of intestinal damage. Regression analysis of ΔVh:Cd vs gluten dose showed that gluten dose explained roughly 18% of the variation in mucosal damage (adjusted R2, 0.18; P = .0001). How an individual responded to the gluten challenge partly reflected the magnitude of the gluten dose.

Table 1.

Patient Data

| Patient ID | Vh:Cd (time, 0 days) | Vh:Cd (time, 42 days) | ΔVh:Cd (time 0 - time 42) | Gluten challenge, g/day | Age range, y | Sex | Anti–TG2-IgA (time, 0 days) | Anti–TG2-IgA (time, 42 days) | Anti–TG2-IgA fold change | Anti–TG2-IgA positivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 6 | 41–50 | F | 7 | 216 | 31 | Pos |

| X | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 6 | 51–60 | F | 6 | 8 | - | Neg |

| AV | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 3 | 61–70 | F | 17 | 183 | 11 | Pos |

| O | 3.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 6 | 51–60 | F | 8 | 146 | 18 | Pos |

| P | 2.7 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 6 | 41–50 | F | 11 | 227 | 21 | Pos |

| AS | 3.2 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 11 | 8 | - | Neg |

| M | 2.9 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 6 | 61–70 | M | 12 | 19 | - | Neg |

| Y | 2.8 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 6 | 51–60 | F | 10 | 10 | - | Neg |

| G | 2.6 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 6 | 31–40 | M | 6 | 240 | 40 | Pos |

| W | 2.6 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 6 | 41–50 | F | 6 | 53 | 9 | Pos |

| AF | 2.7 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 3 | 41–50 | M | 23 | 40 | - | Baseline pos |

| R | 3 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 6 | 61–70 | F | 7 | 10 | - | Neg |

| AW | 2.8 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 3 | 41–50 | F | 15 | 85 | 6 | Pos |

| K | 2.4 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 6 | 41–50 | F | 15 | 282 | 19 | Pos |

| CM | 2.8 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 41–50 | F | 10 | 72 | 7 | Pos |

| AQ | 2.4 | 0.4 | 2 | 3 | 61–70 | F | 10 | 22 | 2 | Pos |

| AY | 2.6 | 0.6 | 2 | 3 | 61–70 | M | 12 | 36 | 3 | Pos |

| AC | 2.3 | 0.3 | 2 | 3 | 61–70 | M | 7 | 11 | - | Neg |

| V | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 6 | 61–70 | F | 10 | 133 | 13 | Pos |

| CX | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 12 | 34 | 3 | Pos |

| AP | 3 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 8 | 88 | 11 | Pos |

| CS | 2.5 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 9 | 8 | - | Neg |

| AH | 2.7 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 3 | 41–50 | F | 10 | 114 | 11 | Pos |

| H | 2 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 6 | 51–60 | F | 109 | 365 | - | Baseline pos |

| AA | 2.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 25 | 59 | - | Baseline pos |

| AG | 2.5 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 11 | 23 | 2 | Pos |

| BK | 2.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 3 | 41–50 | M | 14 | 24 | 2 | Pos |

| S | 2.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 6 | 61–70 | F | 11 | 14 | - | Neg |

| AN | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3 | 41–50 | F | 16 | 5 | - | Neg |

| AU | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 3 | 61–70 | M | 22 | 21 | - | Baseline pos |

| DK | 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 9 | 8 | - | Neg |

| AL | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 11 | 52 | 5 | Pos |

| AI | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 8 | 95 | 12 | Pos |

| AK | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 3 | 61–70 | F | 15 | 7 | - | Neg |

| AE | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 3 | 71–80 | M | 8 | 67 | 8 | Pos |

| T | 2.9 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 6 | 61–70 | M | 7 | 15 | - | Neg |

| AD | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 50 | 41 | - | Baseline pos |

| DF | 2.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 51–60 | M | 6 | 4 | - | Neg |

| L | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 6 | 61–70 | M | 23 | 209 | - | Baseline pos |

| AM | 3.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 6 | 6 | - | Neg |

| CE | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 61–70 | M | 10 | 21 | 2 | Pos |

| DC | 2.9 | 2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 51–60 | F | 7 | 5 | - | Neg |

| CA | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 31–40 | F | 8 | 7 | - | Neg |

| DZ | 3.2 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 6 | 5 | - | Neg |

| CG | 2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 6 | 8 | - | Neg |

| DQ | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 4 | 3 | - | Neg |

| DY | 3 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 7 | 5 | - | Neg |

| DB | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 41–50 | M | 9 | 6 | - | Neg |

| C | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 6 | 21–30 | F | 74 | 239 | - | Baseline pos |

| CN | 3.1 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 71–80 | F | 14 | 11 | - | Neg |

| AT | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 3 | 41–50 | M | 25 | 70 | - | Baseline pos |

| DG | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 3 | 3 | - | Neg |

| U | 2.5 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 6 | 51–60 | F | 15 | 32 | 2 | Pos |

| DH | 3.3 | 3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 6 | 4 | - | Neg |

| DW | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 61–70 | M | 8 | 6 | - | Neg |

| A | 2.9 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 6 | 41–50 | F | 47 | 43 | - | Baseline pos |

| CB | 3 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 31–40 | F | 17 | 32 | 2 | Pos |

| CJ | 3 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 8 | 7 | - | Neg |

| DR | 2.9 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 8 | 6 | - | Neg |

| AO | 2.9 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 14 | 16 | - | Neg |

| DJ | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 16 | 11 | - | Neg |

| Q | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 6 | 61–70 | M | 13 | 32 | 2 | Pos |

| N | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0 | 6 | 51–60 | M | 8 | 10 | - | Neg |

| DN | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0 | 1.5 | 61–70 | M | 14 | 12 | - | Neg |

| DP | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0 | 1.5 | 51–60 | M | 7 | 6 | - | Neg |

| DM | 1.3 | 1.4 | -0.1 | 1.5 | 41–50 | F | 13 | 12 | - | Neg |

| AJ | 2.5 | 2.6 | -0.1 | 3 | 51–60 | F | 13 | 16 | - | Neg |

| DX | 2.9 | 3.1 | -0.2 | 1.5 | 61–70 | F | 10 | 6 | - | Neg |

| CT | 2.8 | 3 | -0.2 | 1.5 | 71–80 | M | 15 | 23 | 2 | Pos |

| AR | 2.3 | 2.6 | -0.3 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 13 | 22 | 2 | Pos |

| DA | 2.4 | 2.8 | -0.4 | 1.5 | 51–60 | F | 36 | 22 | - | Baseline pos |

| AX | 2.8 | 3.3 | -0.5 | 3 | 51–60 | M | 20 | 19 | - | Baseline pos |

| AB | 2.3 | 3.4 | -1.1 | 3 | 41–50 | M | 9 | 9 | - | Neg |

NOTE. Parameters associated with the gluten challenge included the amount of gluten ingested daily for 42 days, the age range (median, 59 y; range, 23–74 y), antisera directed against TG2-IgA (anti-TG2-IgA) expressed in intensity units for both baseline and 42 days, and anti–TG2-IgA that was positive (pos) or negative (neg) above threshold (20 intensity units) at 42 days. Several patients were above threshold for anti–TG2-IgA at baseline (baseline pos). Anti–TG2-IgA fold change was expressed in intensity units, which may or may not reflect linearity pending assay validation.

F, female; M, male.

Figure 1.

Gluten-dependent intestinal mucosal injury as a clinical end point in a human clinical study. Vh:Cd, a histologic measure of mucosal health, was determined at baseline and at the 6-week time point. ΔVh:Cd, defined as baseline minus the 6-week Vh:Cd, represents intestinal damage (positive number) or healing (negative number) over the 6-week timeframe. The bar graph shows the number of patients (y-axis) with a given ΔVh:Cd (x-axis) for a total of 73 patients. The number of patients for a given ΔVh:Cd was subdivided further to indicate the amount of gluten ingested daily per patient, which was 6 (blue, 20 patients), 3 (yellow, 26 patients), and 1.5 (grey, 27 patients) grams of gluten daily for 6 weeks.

We were interested in wide variations in gluten-induced ΔVh:Cd across the data set, which we observed. The question we investigated in this study was whether mucosal damage correlated with an immune response, irrespective of the nominal amount of gluten administered daily.

Genes Differentially Expressed in B and T Cells

The experimental design was to isolate only CD19+ B cells and CD3+ T cells from whole blood, which enabled a simplified analysis of gene expression data focusing solely on genes highly enriched in B and T cells. With this design, our goal was to reduce the noise associated with analyzing global gene expression. For this purpose, we used two published gene lists derived from DNA microarray analyses of fractionated human leukocytes (Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34). The overlap in the B-cell gene lists between Bindea et al33 (23 genes) and Newman et al34 (38 genes) was 15 genes. The overlap in the T-cell gene lists between the sum of all 11 T-cell subpopulations from Bindea et al33 (185 genes) and the single T-cell list from Newman et al34 (99 genes) was 33 genes. The two studies have more agreement than one would expect by chance but less than ideal agreement in defining differential B- and T-cell gene expression. Lymphocytes are diverse, the methods used to purify these diverse cells vary, and differential gene expression is a relative measure that compares expression with other leukocytes. Given these complexities, it is beneficial to use both studies to define the most relevant genes. We started with comprehensive B- and T-cell gene lists, and ultimately set out to refine these lists to obtain a gene signature that correlated more specifically with gluten-induced intestinal injury in CeD.

The B- and T-cell gene lists (see the Materials and Methods section and Supplementary Table 1) obtained from each publication were used separately to analyze the CeD data set.

ΔVh:Cd Correlates With B-Cell Gene Expression

By using DNA microarrays, we measured genome-wide gene expression in a purified pool of B and T cells taken from each patient at baseline and at the 6-week time points. We calculated the net change (baseline to 6 weeks) in B- and T-cell gene expression for each of the published B- and T-cell gene lists and correlated this change with the net change in Vh:Cd.

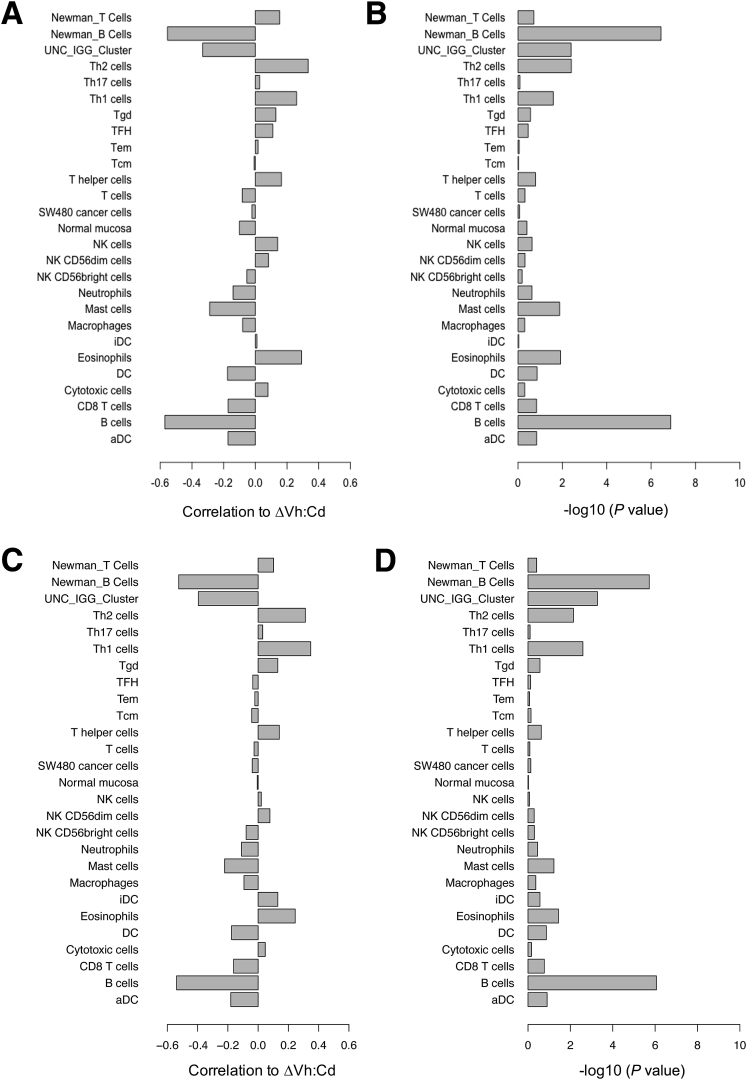

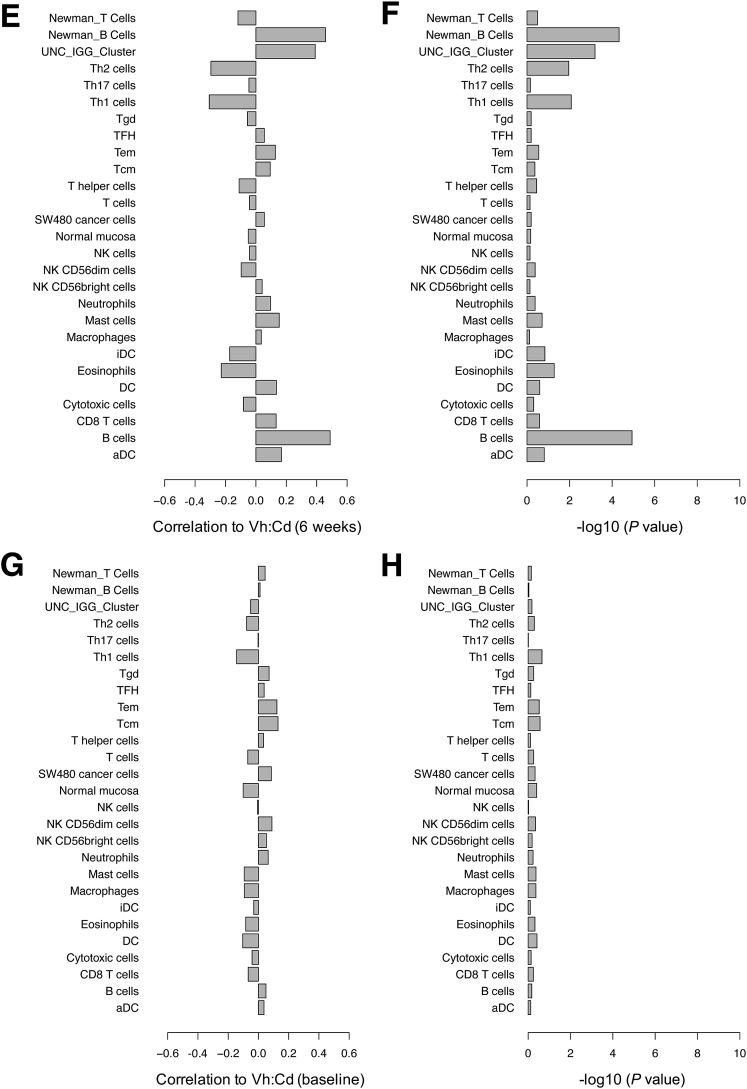

Results showed that the net change in expression of B-cell genes from Bindea et al33 (corr. -0.54; P = 8.7E-07) and Newman et al34 (corr. -0.52; P = 1.9E-06) correlated (corr.) strongly with ΔVh:Cd (Figure 2A and B). It was a negative correlation, which means that B-cell genes were expressed relatively strongly in patients with little to no ΔVh:Cd and relatively poorly in patients with large ΔVh:Cd. Two gene lists from Bindea et al33 representing T-cell subpopulations showed weak positive correlation to ΔVh:Cd, including Th1 (corr. 0.34; P = 0.2.58E-03) and Th2 (corr. 0.31; P = 7.21E-03). In this case, opposite to B-cell genes, T-cell genes were expressed relatively strongly in patients with large ΔVh:Cd and relatively poorly in patients with little to no ΔVh:Cd. Other T-cell gene lists defined by Bindea et al33 showed little to no correlation, including T CD8+, T helper, T, T central memory, T effector memory, T follicular helper, T γδ, and Th17. The T-cell gene list from Newman et al34 also showed no correlation to ΔVh:Cd (corr. 0.10; P = 3.92E-01). Not surprisingly, gene lists corresponding to other leukocytes showed little to no correlation because B and T cells were the only cells analyzed in this study. The University of North Carolina IgG gene signature,35 which contains several known B-cell genes that predict favorable outcomes in breast cancer patients, showed a moderate negative correlation with ΔVh:Cd.

Figure 2.

Spearman rank correlation of gene signatures with the extent of gluten-induced intestinal injury. Gene lists obtained from three publications corresponded to B- and T-cell populations, other leukocytes, cancer cells, and normal mucosa (y-axis). All gene lists were obtained from Bindea et al,33 except for B- and T-cell lists from Newman et al34 (as indicated) and the University of North Carolina (UNC) IgG cluster from Fan et al.35 (A) The mean expression profile for a given gene list was correlated with ΔVh:Cd and the correlation was reported on a scale of 0 to 1 (x-axis). Multiple microarray probes corresponding to a single gene were consolidated to a single probe by taking only the probe with the greatest SD of expression across the 73 patients. (B) Significance for each correlation in panel A was expressed as a P value. Gene signatures also were correlated with (C) ΔVh:Cd, (E) end-of-study Vh:Cd, and (G) baseline Vh:Cd using mean expression profiles and all probes representing a given gene. Significance for each correlation in panels C, E, and G was expressed as a P value in panels D, F, and H, respectively. aDC, activated dendritic cell; DC, dendritic cell; iDC, immature dendritic cell; NK, natural killer; Tcm, T central memory; Tem, T effector memory; TFH, T follicular helper; Tgd, T gamma delta.

Nearly identical results were obtained irrespective of whether multiple microarray probes corresponding to one gene were reduced to a single probe (Figure 2A and B) or whether all probes were analyzed (Figure 2C and D) (see the Materials and Methods section).

In addition to ΔVh:Cd, we correlated gene expression to baseline and end-of-study (week 6) Vh:Cd for all 73 patients. Results showed that the net change in expression of B-cell genes from Bindea et al33 (corr. 0.49; P = .1.16E-05) and Newman et al34 (corr. 0.46; P = 4.71E-05) correlated with end-of-study Vh:Cd (Figure 2E and F) and was only slightly weaker than that observed for ΔVh:Cd. The correlation was positive, which suggests that a reduction in B-cell gene expression over the 6-week gluten challenge (end-of-study minus baseline) was associated with a smaller end-of-study Vh:Cd. Th1 (corr. -0.31; P = .0084) and Th2 (corr. -0.30; P = .011) gene expression was correlated negatively with the end-of-study Vh:Cd, albeit modestly, which is consistent with results obtained from the ΔVh:Cd analysis. There was no correlation of gene expression with baseline Vh:Cd (Figure 2G and H).

Serum Anti-TG2 Correlates With ΔVh:Cd and the Core B-Cell Gene Module

Sixty-two of 73 patients (85%) were negative at baseline for serum antibodies directed against TG2 (anti–TG2-IgA) (Table 1, threshold for positivity was 20 intensity units). For those 62 patients who were negative at baseline, 42% seroconverted to a positive value over the course of a 6-week gluten challenge. By using a Student t test (unpaired, 2-sided) to compare means, and excluding baseline-positive patients, we determined that anti–TG2-IgA positivity correlated with ΔVh:Cd (P = .0029) and the core B-cell gene module (P = .0022). These results showed that anti-TG2 correlated with B-cell gene expression as well as it did with ΔVh:Cd. A positive anti-TG2 was associated with reduced B-cell gene expression and increased intestinal damage over the course of 6 weeks.

A Subset of B-Cell Genes Drives Correlation to ΔVh:Cd

In the correlation analyses, probes were averaged to generate a mean expression profile across the entire gene list, which then was correlated to ΔVh:Cd; individual genes or probes were not analyzed separately. We asked whether all or a fraction of the genes in the two published B-cell gene lists from Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 correlated with ΔVh:Cd. To define a core set of B-cell genes that drives the correlation, all probes in the two B-cell gene lists were consolidated into a single list and then the probes were ranked separately based on their ability to correlate with ΔVh:Cd. There were 63 unique probes between the two B-cell gene lists, representing 48 unique genes. Of these, 28 probes representing 24 unique genes significantly correlated with ΔVh:Cd (P < .01). We defined these 28 probes as a core B-cell gene module representing a subset of known B-cell genes (see Table 2 for genes). The gene SPIB, present in both the Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 B-cell gene lists, showed the strongest correlation to ΔVh:Cd (corr. -0.56; P = 2.5E-07) (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Gene Symbols and the Corresponding Illumina Microarray Probe IDs Representing the Core B-Cell Gene Module, Non-correlating B-Cell Gene List, and the Extended Core B-Cell Gene Module

| Core B-cell gene module | Non-correlating B-cell gene list | Extended core B-cell gene module | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Probe ID | Gene | Probe ID | Gene | Probe ID | B-cell expression |

| All probes from core B-cell gene module plus the following | ||||||

| ADAM28 | ILMN_1664631 | ABCB4 | ILMN_1767349 | AFF3 | ILMN_1775235 | 1 |

| ALOX5 | ILMN_1680996 | BACH2 | ILMN_1670695 | ALS2CR13 | ILMN_1739942 | ND |

| BACH2 | ILMN_2058468 | BLNK | ILMN_2142935 | BASP1 | ILMN_1651826 | 3 |

| BANK1 | ILMN_1661646 | CCR9 | ILMN_2337386 | BTK | ILMN_1662026 | 4 |

| BCL11A | ILMN_1659800 | CCR9 | ILMN_1664316 | C22ORF13 | ILMN_1764410 | ND |

| BCL11A | ILMN_1752899 | CD180 | ILMN_1665647 | C4ORF34 | ILMN_2224907 | ND |

| BCL11A | ILMN_2255133 | CD1C | ILMN_1654210 | CD24 | ILMN_2060413 | 4 |

| BCL11A | ILMN_2342271 | CD40 | ILMN_2367818 | CD74 | ILMN_1736567 | 3 |

| BLK | ILMN_1668277 | CD79B | ILMN_1710017 | CD74 | ILMN_2379644 | 3 |

| BLR1 | ILMN_2337928 | CD79B | ILMN_1785439 | CD79A | ILMN_1734878 | 4 |

| CD19 | ILMN_1782704 | CD79B | ILMN_2366212 | CNTNAP2 | ILMN_1690223 | 1 |

| CD22 | ILMN_1792075 | COCH | ILMN_1711514 | CXXC5 | ILMN_1745256 | ND |

| CD37 | ILMN_1786176 | CR2 | ILMN_1684724 | CYBASC3 | ILMN_2129505 | ND |

| CD37 | ILMN_2375825 | CR2 | ILMN_2369666 | FAIM3 | ILMN_1775542 | 2 |

| CD40 | ILMN_1779257 | EAF2 | ILMN_1708798 | FCRLA | ILMN_1691071 | ND |

| CD72 | ILMN_1723004 | FCGR2B | ILMN_1804174 | GGA2 | ILMN_1686152 | 3 |

| CD79A | ILMN_1659227 | FCGR2B | ILMN_2382403 | HLA-DQB1 | ILMN_1661266 | 2 |

| FCER2 | ILMN_1662451 | FCGR2B | ILMN_1660027 | HLA-DRB4 | ILMN_1752592 | 5 |

| GNG7 | ILMN_1728107 | FCRL2 | ILMN_1665152 | KIAA0746 | ILMN_1797822 | 3 |

| HHEX | ILMN_1762712 | FCRL2 | ILMN_1791329 | LYN | ILMN_1781155 | 3 |

| HLA-DOB | ILMN_1700428 | KIAA0125 | ILMN_1707491 | MARCKS | ILMN_1807042 | 2 |

| HLA-DQA1 | ILMN_1808405 | LOC653980 | ILMN_1659943 | MDS028 | ILMN_1701244 | 2 |

| OSBPL10 | ILMN_1669497 | LOC91353 | ILMN_2083066 | NAPSB | ILMN_2109416 | ND |

| PNOC | ILMN_1676003 | MEF2C | ILMN_1742544 | PLCG2 | ILMN_1815719 | 3 |

| RASGRP3 | ILMN_1727045 | MS4A1 | ILMN_2401714 | PTPN6 | ILMN_1738675 | 3 |

| SPIB | ILMN_2143314 | MS4A1 | ILMN_1776939 | SEMA4B | ILMN_1672589 | ND |

| TCL1A | ILMN_1788841 | P2RX5 | ILMN_1677793 | SIDT2 | ILMN_1791912 | 2 |

| VPREB3 | ILMN_1700147 | P2RY14 | ILMN_2258409 | SNX2 | ILMN_1691575 | 3 |

| P2RY14 | ILMN_2342835 | SWAP70 | ILMN_1785175 | 4 | ||

| RALGPS2 | ILMN_1654692 | SYK | ILMN_2059549 | 4 | ||

| RALGPS2 | ILMN_2276290 | TLR10 | ILMN_2414762 | ND | ||

| RALGPS2 | ILMN_1813703 | |||||

| RNASE6 | ILMN_1780533 | |||||

| SCN3A | ILMN_2387395 | |||||

| TNFRSF17 | ILMN_1768016 | |||||

NOTE. Immgen data browser (available: http://www.immgen.org/databrowser/index.html, datagroup; human immune cells, Garvan) was used to quantify the relative amounts of B- and T-cell gene expression for 30 genes in the extended core B-cell gene module (as indicated) using an arbitrary scale from 1 to 5: 5, expressed in B cells 10-fold more than other leukocytes; 4, expressed in B cells 10-fold more than T cells; 3, expressed in B cells between 3- and 10-fold more than T cells; 2, expressed in B and T cells with less than 3-fold differential; 1, poorly measured.

ND, no data.

Expression levels for all 28 probes in the core B-cell gene module were averaged across the data set, and the mean expression profile was correlated to ΔVh:Cd. The core B-cell gene module correlated strongly with ΔVh:Cd (corr. -0.59; P = 3.3E-08). As expected, all 28 single probes correlated strongly with the mean expression profile (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, for the remaining 35 B-cell probes (24 unique genes) that correlated poorly as single probes (P > .01), in the aggregate, the mean expression profile across all 35 probes also correlated poorly (corr. -0.24; P = 3.8E-02). We refer to the published B-cell genes that correlated poorly with ΔVh:Cd as the non-correlating B-cell gene list (see Table 2 for genes). Correlations and P values comparing the relative performance of relevant gene lists are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Spearman Correlation of B- and T-Cell Gene Lists With ΔVh:Cd

| Gene list | Correlation | P value |

|---|---|---|

| All B-cell genes Bindea et al33 | -0.54 | 8.74E-07 |

| All B-cell genes Newman et al34 | -0.52 | 1.90E-06 |

| Core B-cell gene module | -0.59 | 3.30E-08 |

| Non-correlating B-cell gene list | -0.24 | 3.80E-02 |

| Single-gene SPIB | -0.56 | 2.50E-07 |

| Extended core B-cell gene module | -0.60 | 2.65E-08 |

| Th1 genes Bindea et al33 | 0.34 | 2.58E-03 |

| Th2 genes Bindea et al33 | 0.31 | 7.21E-03 |

| All T-cell genes Newman et al34 | 0.10 | 3.92E-01 |

NOTE. Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 refer to the authors of the published B- and T-cell gene lists. Correlation was negative or positive, as indicated. The core B-cell gene module and non-correlating B-cell gene list were analyzed by taking all probes for a given gene (probes). The other gene lists used only the probe with the highest SD across the data set (genes) (see the Materials and Methods section for more detail). Th1 and Th2 refer to T-cell subpopulations as defined by Bindea et al.33

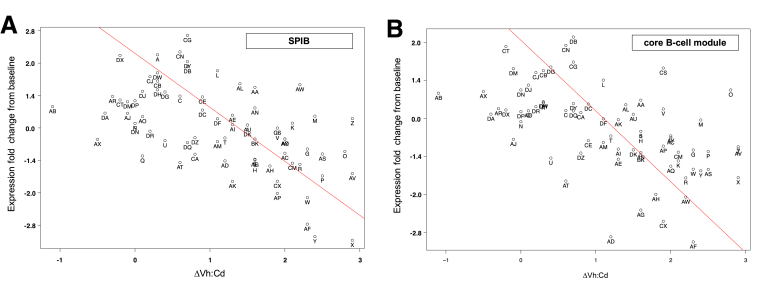

Point plots showed the scatter associated with the relationship between ΔVh:Cd and the net change in gene expression for the single-probe SPIB (Figure 3A) and the mean expression of all 28 probes in the core B-cell gene module (Figure 3B). Seventy-three patients were scattered fairly uniformly on both sides of the regression line over the entire spectrum of intestinal damage.

Figure 3.

Point plots comparing the net change in B-cell gene expression with ΔVh:Cd for 73 patients. (A) The single-gene SPIB or (B) the mean expression across all 28 probes in the core B-cell gene module was used to analyze the net change in B-cell gene expression (end-of-study minus baseline). The regression line is shown in red.

The Extended Core B-Cell Gene Module

Genes representing the core B-cell gene module and the non-correlating B-cell gene list were obtained exclusively from the Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 curated gene lists. We asked whether the core B-cell gene module could be used to discover additional disease-relevant genes that were not included in the Bindea et al33 and Newman et al34 published gene lists. To this end, we took the Spearman correlation between the mean expression profile of the core B-cell gene module and all 20,624 probes in the CeD data set. Significance was assessed using a t test and the Bonferroni correction. Forty-three unique genes (48 probes) (Supplementary Table 2) showed strong correlation to the mean expression profile (r > 0.7; corrected P < 8.3E-8). Twenty-nine unique genes (31 probes) identified in this analysis were not found in the core B-cell gene module. The combination of the core B-cell gene module (24 genes, 28 probes) with genes that shared a similar expression profile to the core module (29 genes, 31 probes) resulted in a list of 53 genes (59 probes) referred to as the extended core B-cell gene module (see Table 2 for genes).

The 29 genes that were added to the core B-cell gene module in the extended list were not obtained from the Bindea et al33 or Newman et al34 curated gene lists. To determine if these 29 genes were expressed differentially in human B cells, we used the Immunological Genome Project (Immgen) data browser, which is based on gene expression studies of fractionated human leukocytes (Garvan data set, GEO GSE3982). The Garvan data set also was used in the Bindea et al33 publication. Half of the 29 genes were expressed differentially in B cells at levels that were at least 3–10 times higher than in T cells (Table 2). None of the 29 genes were known to be expressed differentially in T cells.

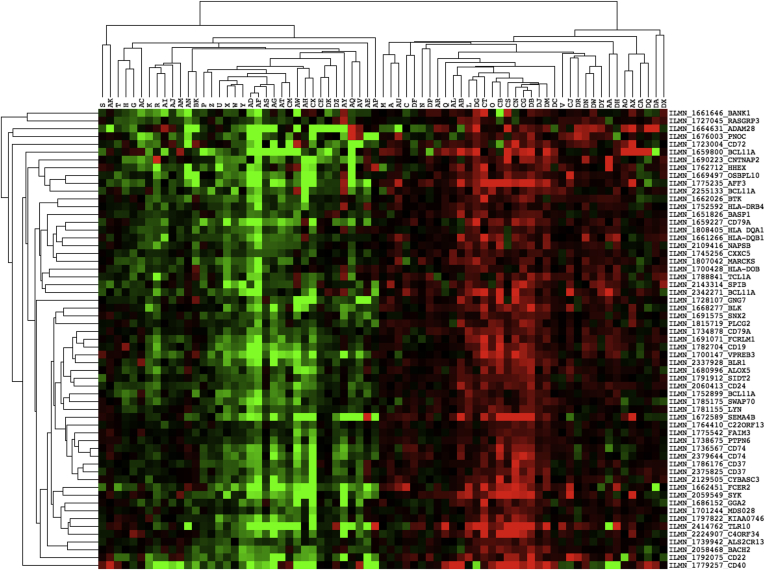

Hierarchical clustering showed that genes contained within the extended core B-cell gene module were expressed similarly across the 73 patients (Figure 4), consistent with the possibility that they are expressed coordinately in B cells. The extended module contained notable genes, including, among others, HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1, the two subunits of HLA-DQ2 that bind gluten. Notable genes that were absent included, among others, MS4A1 (CD20), CD79B, CR2, and FCRL2, despite the observation that all four genes were represented by multiple probes on the microarray. The extended core B-cell gene module is therefore a portrait of B-cell gene expression that correlated strongly (corr. -0.60; P = 2.65E-08) with autoimmune clinical outcomes in CeD.

Figure 4.

Clustergram of extended core B-cell gene module using Java Treeview. Gene symbols and Illumina microarray IDs are shown for each probe. Centered data were used to show a relative increase (red), decrease (green), or median level of expression (black) for each gene across the 73 patient data set. Dendograms on both axes represent similarity in expression for 59 probes (horizontal) and 73 patients (vertical). The preclustering data file is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Immune Response in Patients With Little to No Gluten-Induced Intestinal Injury

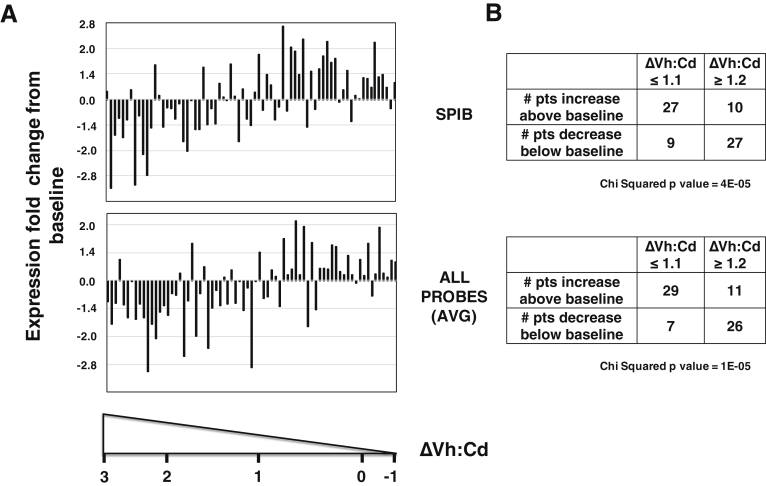

Two plausible hypotheses may explain how a change in B-cell gene expression correlates with gluten-induced intestinal injury (ΔVh:Cd) over the 6-week study period. First, patients with little to no ΔVh:Cd could maintain a constant level of B-cell gene expression from their baseline start to study conclusion, whereas those with a larger ΔVh:Cd may reduce expression of B-cell genes. Alternatively, patients with little to no ΔVh:Cd actually could increase B-cell gene expression above their baseline starting levels, whereas those with a larger ΔVh:Cd simply maintain or decrease expression. In either scenario, the conclusion is the same. A relative increase in expression of B-cell genes correlated with tolerance to gluten (little to no ΔVh:Cd), whereas their relative decrease correlated with gluten-induced intestinal injury (larger ΔVh:Cd). To distinguish between these two possibilities, we compared uncentered microarray data from both baseline and 6-week time points. To illustrate this point, we compared the expression of SPIB with the mean expression of all 28 probes in the core B-cell gene module. By 6 weeks, we found that the single-probe SPIB (Figure 5A, top panel) and the aggregate mean (Figure 5A, lower panel) increased expression above baseline for most patients who showed little to no intestinal injury (ΔVh:Cd ≤ 1.1; 36 patients). Conversely, in most patients with larger intestinal injury (ΔVh:Cd ≥ 1.2; 37 patients), both the single-probe SPIB and the aggregate mean decreased expression relative to their baseline levels (Figure 5A). The number of patients that increased or decreased expression was statistically significant (Figure 5B). These results were used qualitatively to suggest that patients who presented clinically with little to no change in the intestinal biopsy after a 6-week gluten challenge actually mounted an immune response by increasing expression of genes within the core B-cell gene module.

Figure 5.

Fold change in B-cell gene expression from baseline to 6 weeks. (A) Log2 transformed data were obtained from Supplementary Table 4. To calculate the expression fold change from baseline (y-axis), the 6-week time point (visit 6 or V6) was subtracted from baseline start (visit 2 or V2) for each of 73 patients. There was more (increase from zero), unchanged (zero), or less (decrease from zero) RNA after the 6-week gluten challenge. For convenience, numbers on the y-axis were changed to remove log2 transformation (fold changes of 0, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 in log2 space became fold changes of 0, 1.4, 2, and 2.8 without log2 transformation) to reflect the actual magnitude of the change. Seventy-three patients (x-axis) were ordered by decreasing gluten-induced intestinal damage (ΔVh:Cd) with actual ΔVh:Cd values of -1, 0, 1, 2, and 3 for reference. B-cell gene expression was represented by SPIB (top panel) or the aggregate average expression of all 28 probes in the core B-cell gene module (all probes average, lower panel). (B) Quantification of the number of patients who increased or decreased expression of SPIB (top panel) and core B-cell gene module (bottom panel) at the 6-week time point relative to baseline. Seventy-three patients were segregated equally into 2 groups based on ΔVh:Cd ≤ 1.1 (36 patients) and ≥ 1.2 (37 patients). The chi-square test was used to determine whether the number of patients who segregated above and below baseline for the 2 groups differed from expected values distributed randomly.

Discussion

In CeD, the immune system mounts a response to dietary gluten, resulting in destruction of small intestinal epithelial cells and tissue remodeling of the gut mucosa. To date, no immune cell in peripheral blood has been shown to correlate with gluten-induced intestinal mucosal damage. Our objective was to identify such an immune cell in peripheral blood with emphasis on B and T lymphocytes. The experimental design included a gluten challenge in patients with CeD who had been following a gluten-free diet for at least a year. We defined oral tolerance from a clinical perspective as the ability to ingest gluten in treated patients diagnosed with CeD without showing a characteristic crypt hyperplastic lesion in the small intestine. In our study, the length of time associated with the gluten challenge (6 weeks) was otherwise sufficient to cause damage in most patients. This experimental design provided a rare and important look into a relatively healthy immune system before and immediately after a possible break in oral tolerance as study participants relapsed to varying degrees in the context of a well-controlled clinical study. Over the 6-week study period, peripheral B, but not T, cells showed a relative increase in gene expression in those individuals with an increasingly healthy or undamaged gut mucosa. Conversely, in those individuals with decreasing mucosal health, peripheral B cells showed a relative decrease in gene expression. The peripheral B cell therefore tracked with oral tolerance across the full spectrum of intestinal damage, from no change to a nearly flat mucosa. This observation can be interpreted in several ways. First, the peripheral B cell may be a biomarker that indicates oral tolerance to gluten but plays no functional role in dampening the inflammatory process. Alternatively, peripheral B cells may function to promote local and peripheral immune tolerance, the hallmark of a regulatory B cell36 whose compromised function has been implicated in both human37 and mouse models38 of autoimmunity.

The peripheral B cells identified in this study satisfy one requirement of a regulatory B cell in that its presence correlates with tolerance. Unfortunately, there are no biomarkers that are specific to regulatory B cells. These cells are not considered a distinct developmental lineage of B cells but rather to have acquired a tolerogenic phenotype in response to environmental cues or specific antigen binding to their B-cell receptor. In addition, regulatory B-cell subsets may be distinct from one another with unique tolerogenic phenotypes. Given these complexities, the peripheral B cell identified in this study may fall within the functional definition of regulatory B39 and T40 cells to dampen intestinal inflammation.

The identification of a functional human regulatory B cell would have potential therapeutic implications for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including CeD. The therapeutic objective would be to restore this peripheral B-cell phenotype that, in the absence of intervention, subsides along with immune tolerance. Depending on tissue specificity and diversity of regulatory B-cell subsets, knowledge obtained using CeD as a model for discovery also may extend to cancer immunotherapy. B cells that migrate into the tumor may acquire a regulatory phenotype that overrides a local antitumor immune response. A therapeutic objective would be to inhibit the tolerogenic phenotype of the regulatory B cell and thus promote the immune response to hematopoietic and solid cancers.

Several patients on the high-gluten dose surprisingly showed weak mucosal damage after the gluten challenge, which contrasts with others in the same cohort and suggests that a subset of CeD patients can maintain oral tolerance to gluten, at least for 6 weeks. Gluten challenges using small and moderate amounts of gluten (1.5–6 g/day) for short times (6–12 wk) in well-treated adult patients with CeD rarely have shown clinically significant mucosal deterioration in all patients. Approximately 30% of subjects did not respond to the short-term gluten challenge.6, 32, 41 To address the issue of oral tolerance longer term, it was observed that the prevalence of CeD in Finland is increasing from childhood (1.5%),42 through adults (2.0%),43 to the elderly (2.7%).44 Although these data can be interpreted several ways, one interpretation is that oral tolerance to gluten is established early and that a break to oral tolerance is more probable later in life after decades of gluten consumption.44, 45 Similarly, when volunteers previously diagnosed with CeD reverted from a gluten-free to a gluten-containing diet many years after their initial diagnosis and with the disease currently in remission, there were subjects who did not break oral tolerance to gluten for more than 2 years.46 One patient relapsed after 7 years and another went 19 years on an unrestricted, gluten-containing diet before the disease relapsed as dermatitis herpetiformis, a gluten-dependent clinical manifestation of CeD.47 These clinical examples suggest that there are mechanisms in at least some CeD patients that promote oral tolerance to gluten. The B-cell gene signature provides biomarkers that may track this tolerogenic, protective mechanism.

The classic definition of oral tolerance is the ability to suppress immune responses to dietary food proteins, such as gluten. We defined oral tolerance to gluten from a clinical perspective, regardless of an immunologic mechanism. From a mechanistic perspective, the regulatory T cell is one possible tolerogenic, protective, cellular mechanism that is known to play a role in suppressing immune responses to dietary food proteins. Most peripheral regulatory T cells in the murine small intestine are induced by dietary proteins from solid foods.48 The dietary proteins from wheat gluten are apparently no exception. Type 1 regulatory T cells conferred oral tolerance to wheat gluten in a murine model of gluten tolerance.49 Macrophages degraded the gluten proteins that in turn stimulated type 1 regulatory T-cell differentiation.50 Oral tolerance is a poorly understood process that involves multiple immune cell populations. We provide correlative evidence in the context of relevant human studies that a regulatory B cell is a strong candidate to promote oral tolerance to gluten.

How a patient responds to a gluten challenge may depend on several variables, including but not limited to the amount of gluten administered, the length of time associated with the challenge, the length of time and stringency of the gluten-free diet, the immune responses that control oral tolerance to gluten, and baseline level of gluten-dependent mucosal injury. Two of these variables deserve further comment. First, it was required that each patient remain on a gluten-free diet for at least one year before enrolling in the study, providing the best possible opportunity to respond to a gluten challenge. In practice, it is nearly impossible to assess the stringency of their gluten-free diet to determine if the patient intentionally but only occasionally consumes gluten, if they risk eating out where they have less control, or if their food source inadvertently is contaminated with gluten. These are limitations associated with human studies that are nearly impossible to quantify. Second, on the last point regarding baseline injury, we observed heterogeneity in baseline Vh:Cd measurements (range, 1.1–3.5), which is a limitation of the study that likely reflects a variability in the CeD population on a gluten-free diet.51 Patients with the highest mucosal injury (Vh:Cd of 1.1, 1.3, and 1.4) still showed further mucosal damage following the 6-week gluten challenge. Ongoing mucosal injury did not preclude a gluten response. It is not known whether patients with ongoing gluten-dependent mucosal injury (smaller Vh:Cd) respond differently to a gluten challenge than patients with less injury (larger Vh:Cd). It is true that patients who start with a Vh:Cd of 1.1 cannot decrease as far as those who start with a Vh:Cd of 3. This may reduce the dynamic range of our analysis, however, it may be less of a concern if a relatively small ΔVh:Cd associated with more baseline injury also reflects a relatively small change in B-cell gene expression. Despite any limitations, we showed strong and important correlations between B-cell gene expression and gluten-dependent gut mucosal injury, which implicates a cellular mechanism of gut inflammation for future study.

A deliberate gluten challenge sometimes is needed to diagnose CeD. A suspected CeD patient may initiate and maintain a gluten-free diet without obtaining a definitive diagnosis. In such instances, to subsequently diagnose the disease, the patient faces the difficult decision to maintain a prolonged gluten challenge followed by serologic tests and potentially undergoing repeated upper gastrointestinal endoscopies with small intestinal biopsies, as the patient waits for the break in oral tolerance to gluten. The strong correlation we observed between B-cell gene expression and ΔVh:Cd suggests that the B-cell signature may be a useful diagnostic tool in this context. Development of such a predictive model will require an accurate determination of the cumulative error associated with measuring ΔVh:Cd. Errors include sampling (number and location), sectioning, and scoring5 intestinal biopsy specimens. Ultimately, biomarkers developed from a peripheral B-cell signature may be used to monitor changes in local gut inflammation from one time point to another. Validation studies should confirm our observation that individuals with CeD vary in their sensitivity or degree of tolerance to gluten, at least by 6 weeks, and that all individuals in this study may have relapsed given more than 6 weeks on a gluten challenge. We hypothesize that the B-cell signature will correlate with relapse when the break to immune tolerance ultimately is observed. It also is noteworthy that, although these B-cell biomarkers were found in peripheral blood, it is not known whether they also localize to disease lesions in the gut.

B-cell populations that differentially express the core B-cell gene module may traffic to and from the gut or reside permanently in peripheral blood. Analogous to T cells,52 if these B cells traffic to the gut, then α4/β7-integrins may be expressed in these cells. Based on our experimental design, it was not possible to address whether integrin expression in B cells was constitutive or inducible from baseline to the 6-week time point. Because we co-purified B and T cells as a single pool, the resulting purified RNA reflects the mixture of B and T cells. Since the number of T cells exceeds that of B cells, and these integrins are expressed in T cells, the purified RNA pool will reflect T-cell expression. Validation studies will expand the repertoire of B-cell–specific biomarkers, including integrins, using more sensitive methodologies. These biomarkers can be used not only to track the location, but also to isolate and characterize the proposed B-cell activity that correlates with immune tolerance in CeD.

A change in the number of B cells relative to T cells in peripheral blood will affect the results of our study where B and T cells were isolated as a pool. Unfortunately, the number of B and T cells at baseline and end-of-study were not quantified. If the number of B cells increased from baseline to end-of-study, then we would expect that all B-cell genes would go up as a unit. We observed that half of the genes (24 of 48 B-cell genes, 35 of 63 B-cell probes, see Table 2, non-correlating B-cell gene list) did not correlate with intestinal injury, which is inconsistent with increases to B-cell numbers only. CD20, CD79B, CR2, and FCRL2 were among the many genes that did not correlate with intestinal injury yet are widely accepted as genes expressed differentially in B cells relative to T cells. We do not rule out the possibility of changes in B-cell numbers, however, the aggregate B-cell population looked qualitatively different by 6 weeks.

We envision several hypothetical scenarios to model how changes in cell number translate to changes in the measured signal. Let us assume the total RNA yield per sample is 100 ng for the B- and T-cell pool and that the number of B cells is roughly 10-fold less than T cells in peripheral blood. If the amount of total RNA used for sample analysis is fixed at 100 ng, 90 ng total RNA comes from T cells and 10 ng comes from B cells. In the first scenario, if the number of B cells and the amount of RNA contributed by B cells were to increase 2-fold, holding T cells constant, we collect an additional 10 ng B-cell RNA and the total RNA yield increases to 110 ng for the B- and T-cell pool. We expect to see the B-cell signal increase nearly 2-fold if 100 ng total RNA is used for analysis. In the second scenario, if the number of T cells and the amount of RNA contributed by T cells were to increase 2-fold, holding B cells constant, then we collect an additional 90 ng RNA and the total RNA yield increases to 190 ng RNA for the B- and T-cell pool. We do not expect to see any increase in the T-cell signal if 100 ng total RNA is used for sample analysis. Changes that occurred in T cells were normalized out if the amount of total RNA hybridized to the array was fixed at 100 ng for both the baseline and end-of-study samples. Finally, in a scenario in which we analyze only B cells without T cells, and assuming the number of B cells and the amount of RNA contributed by B cells were to increase 2-fold, then the total RNA yield increases from 10 ng at baseline to 20 ng at end-of-study. We expect that normalization during microarray analysis will completely eliminate the 2-fold increase in the B-cell signal if 10 ng total RNA is used for sample analysis. In this respect, the T-cell RNA fortuitously serves as an internal control that makes it possible to visualize a 2-fold increase in the number of B cells described in scenario 1. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction and cell counts will be required in validation studies to resolve the ambiguities associated with variations in the ratio of B to T cells. Complexities associated with relative changes in cell numbers are expanded greatly when peripheral blood mononuclear cells or tissues are used for analyses. In comparison, the decision to use purified B and T cells was an advantage and not a disadvantage of the current experimental design.

There are two scenarios in which the current experimental design performs well even in the absence of cell counts or quantitative polymerase chain reaction. First, if the aggregate B-cell gene expression changes for some genes and not others, and the number of B and T cells remains constant from baseline to end-of-study, we expect to visualize these changes for both B and T cells. This scenario includes B- and T-cell subsets that repopulate or traffic to/from peripheral blood. Second, if the number of T cells and the amount of RNA contributed by T cells were to increase 2-fold in a small subset (say 10%) of T cells, then this scenario for T cells is nearly identical to B cells. Given markers specific for this T-cell subset, say Th1, we expect to see the change. Perhaps this is why we observed a small direct correlation of Th1 and Th2 gene expression with intestinal injury. T-cell subsets that otherwise would correlate strongly with ΔVh:Cd but lack unique gene identifiers will not be detected, which is a limitation of the current study design. For example, it was not possible to analyze a contribution for regulatory T cells because the number of unique genes that distinguish this T-cell subset from other T cells was limited. Without unique identifiers, a regulatory T cell will not significantly influence shared gene expression profiles in the aggregate CD3+ T-cell population.

The genes that we used for analysis were markers of B- and T-cell differentiation. Using B cells as an example, many of these genes are implicated in B-cell–receptor signaling, hence their differential expression in B cells and their selection as B-cell markers. Even if we assume a functional correlation between B cells and immune tolerance to gluten, it would be premature, although intriguing, to speculate on the possibility of modulating B-cell–receptor signaling and B-cell activation thresholds to promote immune tolerance to gluten. Importantly, it should not be inferred that these are the only genes differentially expressed between tolerance and the lack of tolerance to gluten. The data do not rule out the possibility that the B cell could modulate immune tolerance by a mechanism that is shared with other cells despite the fact that we were not able to use these shared genes in our analysis. Exactly if and how the B cell functions to promote immune tolerance will require partial purification and characterization of the proposed cellular activity. The genes that drive its proposed cellular function may extend beyond the gene lists used for analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work benefitted from data assembled by the Immgen consortium.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Markku Mäki is a scientific advisor to ImmusanT, Inc, and Celimmune LLC; Daniel Adelman is a scientific advisor to ImmunogenX, Inc. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Mitchell E. Garber conceptualized the study; Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, and Markku Mäki were responsible for the methodology; Alok Saldanha and Joel S. Parker were responsible for the software; Alok Saldanha validated the study; Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, and Wendell D. Jones performed the formal analysis; Mitchell E. Garber, Kaija Laurila, and Katri Kaukinen performed the investigation; Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, Marja-Leena Lähdeaho, Daniel C. Adelman, and Markku Mäki provided resources; Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, Wendell D. Jones, and Kaija Laurila curated data; Mitchell E. Garber wrote the original draft; Mitchell E. Garber, Wendell D. Jones, Purvesh Khatri, Chaitan Khosla, Daniel C. Adelman, and Markku Mäki reviewed the writing and edited the paper; Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, and Wendell D. Jones were responsible for visualization; Mitchell E. Garber, Chaitan Khosla, Daniel C. Adelman, and Markku Mäki supervised the study; Mitchell E. Garber, Daniel C. Adelman, and Markku Mäki were responsible for project administration; and Mitchell E. Garber, Alok Saldanha, Joel S. Parker, Chaitan Khosla, Daniel C. Adelman and Markku Mäki acquired funding. Categories were defined by CRediT.53

Funding This study was funded by Alvine Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and grants from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (to Alvine Pharmaceuticals), from the Competitive State Research Financing of the Tampere University Hospital (M.M. and K.K.), from the Academy of Finland Research Council for Health (K.K.), and in part from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK063158 to C.K.). M.E.G. was supported part time during the writing of this manuscript by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK063158 to C.K.). All authors currently have no financial or nonfinancial competing interests in Alvine Pharmaceuticals, which had a role in the clinical study design and collection of biopsy and blood samples, but no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation associated with the biopsies, blood samples, and genomic data used in this study. Alvine Pharmaceuticals had no role in writing this report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Pabst O., Mowat A.M. Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:232–239. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro M., Nunes-Miranda J.D., Branlard G. One hundred years of grain omics: identifying the glutens that feed the world. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:4702–4716. doi: 10.1021/pr400663t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuitunen P., Kosnai I., Savilahti E. Morphometric study of the jejunal mucosa in various childhood enteropathies with special reference to intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1982;1:525–531. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurppa K., Collin P., Viljamaa M. Diagnosing mild enteropathy celiac disease: a randomized, controlled clinical study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:816–823. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taavela J., Koskinen O., Huhtala H. Validation of morphometric analyses of small-intestinal biopsy readouts in celiac disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leffler D., Schuppan D., Pallav K. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013;62:996–1004. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leffler D., Kupfer S.S., Lebwohl B. Development of celiac disease therapeutics: report of the Third Gastroenterology Regulatory Endpoints and Advancement of Therapeutics Workshop. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:407–411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindryckx P., Levesque B.G., Holvoet T. Disease activity indices in coeliac disease: systematic review and recommendations for clinical trials. Gut. 2016 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312762. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorsby E. Invited anniversary review: HLA associated diseases. Hum Immunol. 1997;53:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(97)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nepom G.T., Erlich H. MHC class-II molecules and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:493–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosnes J., Cellier C., Viola S. Incidence of autoimmune diseases in celiac disease: protective effect of the gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green P.H., Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1731–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sollid L.M., Lie B.A. Celiac disease genetics: current concepts and practical applications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:843–851. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tollefsen S., Arentz-Hansen H., Fleckenstein B. HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 signatures of gluten T cell epitopes in celiac disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2226–2236. doi: 10.1172/JCI27620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamnaes J., Sollid L.M. Celiac disease: autoimmunity in response to food antigen. Semin Immunol. 2015;27:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korponay-Szabó I.R., Halttunen T., Szalai Z. In vivo targeting of intestinal and extraintestinal transglutaminase 2 by coeliac autoantibodies. Gut. 2004;53:641–648. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaukinen K., Peraaho M., Collin P. Small-bowel mucosal transglutaminase 2-specific IgA deposits in coeliac disease without villous atrophy: a prospective and randomized clinical study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:564–572. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paparo F., Petrone E., Tosco A. Clinical, HLA, and small bowel immunohistochemical features of children with positive serum antiendomysium antibodies and architecturally normal small intestinal mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2294–2298. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tosco A., Maglio M., Paparo F. Immunoglobulin A anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody deposits in the small intestinal mucosa of children with no villous atrophy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:293–298. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181677067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmi T.T., Collin P., Jarvinen O. Immunoglobulin A autoantibodies against transglutaminase 2 in the small intestinal mucosa predict forthcoming coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:541–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesin L., Sollid L.M., Di Niro R. The intestinal B-cell response in celiac disease. Front Immunol. 2012;3:313. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobeika E., Maity P.C., Jumaa H. Control of B cell responsiveness by isotype and structural elements of the antigen receptor. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanzavecchia A. Antigen-specific interaction between T and B cells. Nature. 1985;314:537–539. doi: 10.1038/314537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.du Pre MF Sollid LM. T-cell and B-cell immunity in celiac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leffler D.A., Green P.H.R., Fasano A. Extraintestinal manifestations of coeliac disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:561–571. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heikkilä K., Pearce J., Mäki M. Celiac disease and bone fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:25–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadjivassiliou M., Mäki M., Sanders D.S. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–377. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000196480.55601.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korpimäki S., Kaukinen K., Collin P. Gluten-sensitive hypertransaminasemia in celiac disease: an infrequent and often subclinical finding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1689–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaukinen K., Halme L., Collin P. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:881–888. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson R.P., Degano P., Godkin A.J. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nat Med. 2000;6:337–342. doi: 10.1038/73200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ráki M., Fallang L.-E., Brottveit M. Tetramer visualization of gut-homing gluten-specific T cells in the peripheral blood of celiac disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2831–2836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608610104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahdeaho M.L., Kaukinen K., Laurila K. Glutenase ALV003 attenuates gluten-induced mucosal injury in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1649–1658. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Tosolini M. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Green M.R. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan C., Prat A., Parker J.S. Building prognostic models for breast cancer patients using clinical variables and hundreds of gene expression signatures. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosser E.C., Mauri C. Regulatory B cells: origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity. 2015;42:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menon M., Blair P.A., Isenberg D.A. A regulatory feedback between plasmacytoid dendritic cells and regulatory B cells is aberrant in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunity. 2016;44:683–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyagaki T., Fujimoto M., Sato S. Regulatory B cells in human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases: from mouse models to clinical research. Int Immunol. 2015;27:495–504. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishima Y., Liu B., Hansen J.J. Resident bacteria-stimulated IL-10-secreting B cells ameliorate T cell-mediated colitis by inducing Tr-1 cells that require IL-27-signaling. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geem D., Ngo V., Harusato A. Contribution of mesenteric lymph nodes and GALT to the intestinal Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell compartment. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lähdeaho M.-L., Mäki M., Laurila K. Small-bowel mucosal changes and antibody responses after low- and moderate-dose gluten challenge in celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mäki M., Mustalahti K., Kokkonen J. Prevalence of celiac disease among children in Finland. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2517–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lohi S., Mustalahti K., Kaukinen K. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1217–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vilppula A., Kaukinen K., Luostarinen L. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mäki M., Holm K., Koskimies S. Normal small bowel biopsy followed by coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1137–1141. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.10.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mäki M., Lähdeaho M.L., Hällström O. Postpubertal gluten challenge in coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1604–1607. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.11.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurppa K., Koskinen O., Collin P. Changing phenotype of celiac disease after long-term gluten exposure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:500–503. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817d8120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim K.S., Hong S.-W., Han D. Dietary antigens limit mucosal immunity by inducing regulatory T cells in the small intestine. Science. 2016;351:858–863. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du Pré M.F., Kozijn A.E., van Berkel L.A. Tolerance to ingested deamidated gliadin in mice is maintained by splenic, type 1 regulatory T cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:610–622. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Leeuwen M.A., Costes L.M.M., van Berkel L.A. Macrophage-mediated gliadin degradation and concomitant IL-27 production drive IL-10- and IFN-γ-secreting Tr1-like-cell differentiation in a murine model for gluten tolerance. Mucosal Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.76. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adelman D., Essenmacher K., Garber M. sa1280 the gluten-free diet alone does not control symptoms and mucosal injury in many patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:S-280. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu H., Ward E.J., Marelli-Berg F.M. Mechanisms of T cell organotropism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:3009–3033. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brand A., Allen L., Altman M. Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit. Learn Publ. 2015;28:151–155. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.