Abstract

Characterization of toxicity associated with cancer and its treatment is essential to quantify risk, inform optimization of therapeutic approaches for newly diagnosed patients, and guide health surveillance recommendations for long-term survivors. The National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) provides a common rubric for grading severity of adverse outcomes in cancer patients that is widely used in clinical trials. The CTCAE has also been used to assess late cancer treatment-related morbidity, but is not fully representative of the spectrum of events experienced by pediatric and aging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Also, CTCAE characterization does not routinely integrate detailed patient-reported and medical outcomes data available from clinically assessed cohorts. To address these deficiencies, we standardized the severity grading of long-term and late-onset health events applicable to childhood cancer survivors across their lifespan by modifying the existing CTCAEv4.03 criteria and aligning grading rubrics from other sources for chronic conditions not included or optimally addressed in the CTCAEv4.03. This manuscript describes the methods of late toxicity assessment used in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) Study, a clinically assessed cohort in which data from multiple diagnostic modalities and patient-reported outcomes are ascertained.

Keywords: childhood cancer, late effects, chronic disease, toxicity

Introduction

Investigators, having achieved remarkable progress in developing curative therapy for pediatric malignancies, now have a responsibility to evaluate cancer-related morbidity and its impact on long-term survivor health and quality of life.(1,2) Previous research has established that childhood cancer survivors commonly experience long-term (persistent) health problems following diagnosis and treatment and are at risk for late-onset health events occurring at rates exceeding those of sibling and population comparison groups.(3–9) The morbidity associated with childhood cancer survival is multifactorial, with patient, treatment, and health care circumstances influencing outcomes.(2) The reported prevalence estimates of specific complications vary by data collection methods (e.g., patient report, registry/administrative data, clinical assessment) as well as time (e.g., from diagnosis, attained age) of assessment. These disparities complicate comparison of research outcomes across studies and challenge the characterization of high risk survivors who may benefit from alternate treatment strategies, heightened surveillance, and preventive or remedial interventions.

Essential to the characterization of high risk morbidity profiles associated with cancer treatment is the use of a common rubric for classifying and grading adverse outcomes. The National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) provides a descriptive terminology that is widely used for grading severity of adverse events observed in clinical trials.(10–12) However, despite significant revisions over time, the current CTCAEv4.03 (10) is still not fully representative of the spectrum of outcomes experienced by pediatric and aging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Moreover, CTCAEv4.03 does not routinely integrate detailed patient-reported and medical outcomes data available from clinically assessed cohorts, which may increase the likelihood of inconsistent assessments among research investigators in long-term follow-up settings. To address these deficiencies, we adopted a standardized severity grading of long-term and late-onset health events to utilize in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) Study population. Specifically, we developed an approach that is applicable to childhood cancer survivors across the lifespan by modifying the existing CTCAEv4.03 criteria and aligning grading rubrics from other sources for conditions not included or optimally addressed in the CTCAEv4.03. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the methods of long-term and late-onset adverse event assessment used in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) Study where data from multiple diagnostic modalities and patient-reported outcomes are ascertained.

Materials and Methods

Study population

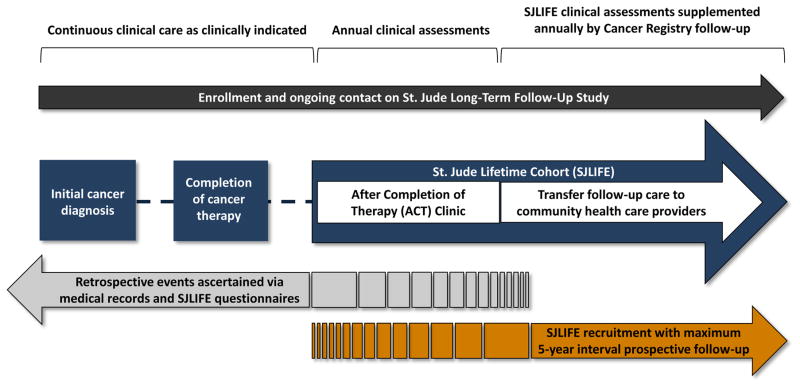

The ongoing institutional review board-approved SJLIFE study was initiated in late 2007 with the aim of facilitating longitudinal evaluation of health outcomes among individuals surviving pediatric cancer.(13) Eligibility criteria for participation in SJLIFE initially included: diagnosis of pediatric cancer treated or followed at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH), attained age of 18 years or older, and survival of 10 or more years from diagnosis. In 2015, eligibility criteria were expanded to include five-year survivors of any age. The SJLIFE study design involves a retrospective cohort with prospective follow-up and ongoing accrual (Figure 1). The retrospective component of SJLIFE utilizes (3–9) data from surviving cancer patients treated at SJCRH since its opening in 1962. During and following treatment of pediatric malignancy, cancer remission status and treatment-related toxicities are routinely monitored by the primary oncology team and/or the long-term follow-up (After Completion of Therapy) clinic until the survivor is 10 years from diagnosis and at least 18 years of age. Data obtained from medical record review of all participants include demographic details, the cumulative doses of specific chemotherapeutic agents, the fields and doses of radiation, information on surgical interventions, primary cancer recurrences and subsequent neoplasms, and acute and late organ-specific toxicity.

Figure 1.

Sources of health outcomes data used in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE) Study where severity grading criteria of long-term and late-onset health events was applied. During and following treatment of pediatric cancer, cancer remission status and treatment-related toxicities are routinely monitored by the primary oncology team and/or the long-term follow-up (After Completion of Therapy) Clinic until the survivor is 10 years from diagnosis and at least 18 years of age. Participants in the SJLIFE cohort are invited to return to SJCRH at least once every five years for follow-up using protocol-based medical evaluations and assessments of patient-reported outcomes, neurocognitive function, and physical performance status. In addition to longitudinal evaluations undertaken as part of SJLIFE, all oncology patients transitioned from SJCRH long-term follow-up care to community providers are followed by the institutional review board-approved St. Jude Long-Term Follow-Up Study (SJLTFU) study. All SJCRH patients are invited to participate in SJLTFU study at diagnosis. Health and vital status of SJLTFU participants are monitored by the St. Jude Cancer Registry and supplemented by periodic National Death Index searches.

In addition to longitudinal evaluations undertaken as part of SJLIFE, all oncology patients transitioned from SJCRH long-term follow-up care to community providers are followed by the institutional review board-approved St. Jude Long-Term Follow-Up Study (SJLTFU) study. All SJCRH patients are invited to participate in SJLTFU study at diagnosis. Health and vital status of SJLTFU participants are monitored by the St. Jude Cancer Registry and supplemented by periodic National Death Index searches.

Following provision of informed consent, participants in the SJLIFE cohort are invited to return to SJCRH at least once every five years for follow-up using protocol-based medical evaluations and assessments of patient-reported outcomes, neurocognitive function, and physical performance status. Permission for release of medical records is requested at each evaluation to validate interim, survivor-reported medical events. Data available through both retrospective health record review and prospective, standardized clinical assessment provides detailed information about symptoms, physical findings, laboratory/diagnostic study results, and clinical interventions to consider in the severity grading of chronic and late health events experienced by cohort members.

Grading of Chronic and Late Onset Health Events

A large and diverse multidisciplinary team reviewed data regarding health events routinely collected as part of the SJLIFE and SJLTFU studies, focusing on persistent health conditions present from diagnosis or developing during or shortly after therapy (long-term) and those developing five or more years after diagnosis (late-onset); congenital conditions and acute cancer- and treatment-related toxicities that subsequently resolved were excluded. The compiled health events were then compared to those in CTCAEv4.03.

The grading criteria for each late effect featured in CTCAEv4.03 were reviewed by the multidisciplinary team. Minor modifications were made to the CTCAE grading schema for some conditions in order to integrate specific diagnostic findings, clinical management, surgical interventions, and patient-reported outcomes with the goal of creating a more transparent and uniformly replicable grading rubric (Table 1). Clinical management was incorporated into the grading criteria to account for the treatment burden and intervention risks among survivors whose adherence to clinical management resulted in normal laboratory and diagnostic testing results.

Table 1.

Examples of Modifications of CTCAEv4.03 and Rationale

| Example | Rationale for modification | CTCAEv4.03 | Modified CTCAEv4.03 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTCAEv4.03 Eye disorders: Other, Specify Visual field deficit |

“Visual field deficit” is not specifically included as an adverse event in CTCAEv4.03. Option of “other” eye disorders is not specific without incorporating patient-reported outcomes relative to performance of ADLs. Grade 4 is eliminated because visual field deficits represented persistent (as opposed to acute) events in long-term survivor cohort. |

|

|

| CTCAEv4.03 Infections and infestations: Hepatitis viral |

With availability of more effective therapy for chronic hepatitis, “Grade 1: asymptomatic; treatment not indicated” was perceived to be inappropriate as symptoms are not the only indication driving treatment decisions. Grade 2 category developed to reflect common presentation with asymptomatic hepatitis and variceal hemorrhage to reflect decompensated liver function. Additional text added to Grade 3 to align with proposed CTCAEv5.0. |

|

|

| CTCAEv4.03 Nervous system disorders: Intracranial hemorrhage |

Text added to clarify neuro-imaging findings consistent with intracranial bleeding in asymptomatic survivors. |

|

|

| CTCAEv4.03 Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders: Bronchospasm |

Text added to clarify integration of routine clinical management into severity grading. |

|

|

| CTCAE v4.03 Investigations: Ejection fraction decreased |

Ejection fraction parameters specified to denote subnormal range and clinically significant decline from baseline. Text added to clarify integration of routine clinical management into severity grading. |

|

|

| CTCAE v4.03 Metabolism and nutrition disorders: Glucose intolerance (Includes: impaired fasting glucose, insulin resistance with impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes mellitus) |

Text added to clarify integration of routine clinical management into severity grading. |

|

|

In addition, pediatric-specific criteria (e.g., bone mineral density deficit) (14) and more conservative diagnostic ranges were used to revise definitions of certain CTCAEv4.03 conditions (e.g., bradycardia and tachycardia) to avoid over-diagnosis based on assessments that fell marginally outside the standard reference ranges. Grading criteria for CTCAEv4.03 events originally designed to capture acute toxicities (e.g., seizures) were modified to facilitate chronic event grading that coincided with the traditional categories [mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe/disabling (grade 3), life-threatening (grade 4) or death (grade 5)].

Chronic and late health events perceived to be relevant to pediatric cancer survivors that were not included or optimally addressed in CTCAEv4.03 were also identified (e.g., liver fibrosis/cirrhosis) (Table 2). Metrics for severity grading of newly identified events were derived from established standards (e.g., body mass index for overweight and underweight pediatric survivors) or developed by multidisciplinary team consensus using a rubric similar to that of the CTCAE. Detailed grading criteria for neuropsychological outcomes were outlined by psychologists incorporating patient-reported outcomes and the results of validated cognitive and psychological measures and comprehensive psychosocial evaluations by study social workers (Supplemental Table 1). Proxy parent-report was used when patient self-report was not appropriate (i.e., young age of participant, severe cognitive impairment). Novel (compared to CTCAE) grading procedures were outlined for the spectrum of benign and malignant subsequent neoplasms experienced by childhood cancer survivors and mapped using histology-based ICD-O-3,(15) in combination with lesion site and surgical ICD9 (16) codes (Table 3). With the exception of amputation, surgical interventions were not graded as a chronic health condition; instead, the clinical or functional consequences of the procedure were graded (e.g., chronic kidney disease following nephrectomy).

Table 2.

Examples of New Grading Criteria Developed to Supplement CTCAEv4.03

| Condition | Rationale for addition/change | New Grading Criteria | Grading Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amputation | CTCAE does not include this adverse event. |

|

ICD-9-CM Diagnosis and Procedure Codes |

| Bone mineral density deficit | CTCAE does not have pediatric-specific criteria for bone mineral density deficits. |

|

International Society of Clinical Densitometry |

| Overweight Obesity | CTCAE categories do not provide pediatric-specific reference ranges. | For age 2 – <20 years

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Seizures | CTCAE categories are more appropriate for acute event versus chronic seizure disorder/epilepsy. |

|

Multidisciplinary team consensus |

| Executive function deficit | CTCAE does not include this adverse event. |

|

Performance on neuropsychological testing of executive functions, including measures of cognitive flexibility/shifting, verbal fluency/initiation, working memory, and self-monitoring |

| Post-traumatic stress* | CTCAE does not include this adverse event. |

|

Validated patient reported outcome measure. Threshold of clinical intervention and impact on ADL |

All grades require exposure to a traumatic event

Table 3.

Severity Grading for Benign and Malignant Neoplasms

| Subsequentneoplasms | CTCAE v4.03 Grading Rubric |

Grading Rubric for St. Jude Lifetime Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | ||

| Benign neoplasms | Neoplasms benign, malignant, and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) Other, specified

|

Low-grade or benign neoplasms where surgical intervention is not indicated, observation or minimally invasive biopsy only [e.g. meningioma followed by MRI only or gastrointestinal polyps diagnosed and resected during colonoscopy] | Any low-grade or benign neoplasm requiring surgical intervention more than a minimally invasive biopsy. Excludes CNS or cardiothoracic surgical interventions. [e.g. fibroadenomas, thyroid adenomas, gastrointestinal polyps requiring surgical resection] | Any low-grade or benign neoplasm requiring CNS or cardiothoracic surgical intervention. [e.g., meningioma or myxoma requiring intervention] | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Malignant neoplasms | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; low-grade neoplasms where intervention is not indicated [e.g. cervical intraepithelial neoplasia/cervical dysplasia/CIN, and teratoma incidentally identified on imaging] | Moderate symptoms; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age appropriate instrumental ADL; low-grade, non-metastatic neoplasms [e.g. cervical carcinoma in-situ, cervical lymph node paraganglioma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, parotid carcinoma] | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care ADL; high-grade neoplasms where single treatment therapy required (surgery, radiation with or without chemotherapeutic agent). [e.g. breast cancer if in-situ, prostate cancer, meningioma requiring intervention, bladder carcinoma, thyroid cancer, carcinoid, squamous cell carcinoma cervix, glioma, astrocytoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor/GIST] | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated; high-grade neoplasms where multimodal therapy required or more than one chemotherapy agent used [e.g. MDS, AML, ALL, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, non in-situ/invasive breast cancer, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor/PNET, soft tissue sarcoma, renal cancer, anaplastic CNS tumor, glioblastoma, carcinoma of head/neck, liver cancer, lung cancer, mesothelioma, melanoma] | Death | |

Results

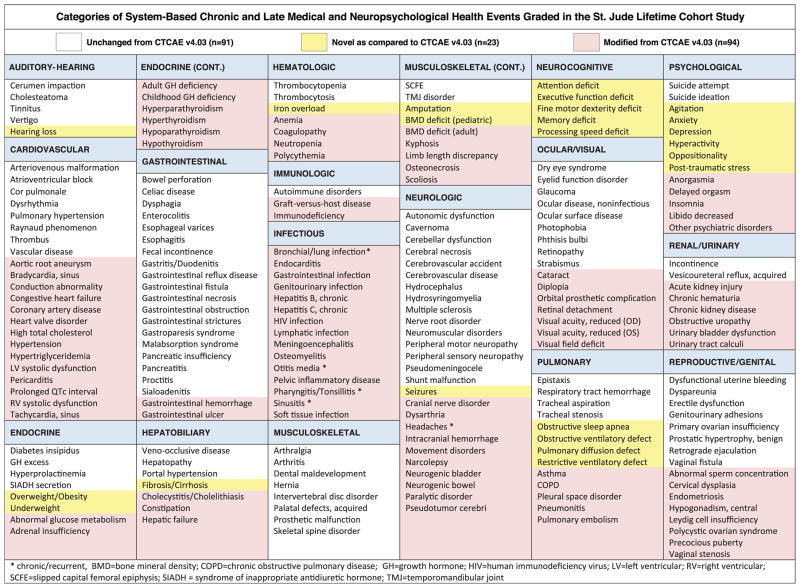

Using organ system-based categories, 190 medical and 18 neuropsychological conditions were selected for late effects grading (Figure 2; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). In all, categories were used as published in CTCAEv4.03 for 91 (44%) conditions/events and modified from those of CTCAE4.03 categories in 94 (45%). Another 23 (11%) required development of new grading criteria for late effects not included in CTCAEv4.03 or for events with CTCAEv4.03 grading not suitable for pediatric or chronic (versus acute) health conditions.

Figure 2.

Categories of system-based chronic and late medical and neuropsychological health events graded in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Among 208 chronic and late-onset medical and neuropsychological conditions, the severity grading was assessed by unmodified categories published in CTCAEv4.03 (n=91, white), modified CTCAEv4.03 categories (n=94, pink) or newly developed grading criteria (n=23, yellow).

Discussion

The majority of individuals treated for cancer during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood will experience extended survival after reaching the 5-year milestone from diagnosis.(1,2) An accurate characterization of cancer-related morbidity is essential to optimize therapeutic approaches for newly diagnosed patients and guide health surveillance recommendations for long-term survivors. The ability to compare outcomes from multiple cohorts requires the use of a common language for the assessment of adverse health events. Historically, CTCAE has provided comprehensive guidelines that enable consistent evaluations of treatment-related toxicity, but its application to cancer survivor cohorts has been limited by a primary focus on acute toxicities and lack of consideration of pediatric-specific reference ranges and developmental health risks.(17)

Challenged with defining the long-term impact of cancer and its treatment in a large cohort of clinically assessed cancer survivors who developed health events across an age spectrum, we modified the CTCAEv4.03 to facilitate consistent and transparent late effects assessment by research team members. Age-appropriate reference ranges were incorporated in the grading criteria for a variety of conditions. Rather than relying on the organ system-specific “other” category for many events, clinically relevant data were added in an effort to augment the grading criteria. Our approach to grading the severity of subsequent neoplasms illustrates how histologic subtype and clinical management were integrated into the assessment of the generic category of “Neoplasms, benign, malignant and unspecified” (Table 3). Inclusion of details about conditions represented within a generic category, diagnostic parameters, and surgical and medical management in grading criteria was perceived by research staff as particularly helpful in improving accuracy and uniformity of assessments. In this regard, we noted that several categories in the proposed CTCAEv5.0 include similar specifications.

As highlighted by previous investigators, guidelines for evaluating adverse events impacting physical and intellectual growth and development in pediatric cancer survivors are not adequately represented in CTCAEv4.03.(17) This deficiency is particularly problematic in the long-term follow-up setting given the high prevalence of endocrine and cognitive late effects associated with specific pediatric cancer therapies.(18–25) Children also experience emotional and psychosocial challenges that are unique from those of adults, necessitating addition of novel categories of pediatric-focused neuropsychiatric outcomes.(20,23,26) Incorporating developmentally sensitive patient-reported outcomes into the grading criteria for many outcomes, especially neuropsychological outcomes (Supplemental Table 1), enhanced our ability to assure that toxicity assessment considered the patient’s perspective and chronic symptoms, which has been reported to be lacking in clinician-based assessments.(27,28)

Our efforts to standardize late effects toxicity assessments for the SJLIFE study should be considered in the context of several limitations. We focused on assessment of late health outcomes and recognize a more thorough consideration of acute toxicity grading criteria in children is also needed. Although comprehensive in our attempts to be inclusive of the wide range of cancer- and treatment-related late effects, it is possible that we have overlooked other adverse events experienced by childhood cancer survivors. Finally, the modifications and additions to the CTCAEv4.03 reflect the opinions of investigators from a single institution. Broader, multi-institutional collaboration will be required to achieve the goal of a common language for the assessment of late effects of pediatric cancer and its treatment across an age spectrum.

Standardized measures for assessing the severity of long-term and late-occurring health conditions in childhood cancer survivors are needed. We believe that the approach adopted for the SJLIFE cohort augments the existing CTCAE rubric in order to allow uniform assessment and grading of toxicities across a wide spectrum of clinical and research environments. This mechanism provides a platform upon which to further develop and harmonize a system that facilitates future collaborative investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Kathy Laub for technical support with manuscript preparation.

Research grant support: Supported by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Cancer Center Support Grant No. 5P30CA021765-33 to C. Roberts, the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study Grant No. U01 CA195547 to M.M. Hudson and L.L. Robison, and American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities to all authors.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, Stratton KK, Bishop K, Krull KR, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:653–63. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Gibson TM, Mertens AC, et al. Reduction in Late Mortality among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:833–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Stratton K, Stovall M, Hudson MM, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Yeo F, Baassiri M, Ehrhardt MJ, Srivastava DK, et al. Cumulative burden of cardiovascular morbidity in paediatric, adolescent, and young adult survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an analysis from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1325–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidler MM, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Kelly J, Jenkinson HC, Skinner R, et al. Long term cause specific mortality among 34 489 five year survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2016;354:i4351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297:2705–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebholz CE, Reulen RC, Toogood AA, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, et al. Health care use of long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4181–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CTEP.Cancer.gov [homepage on the Internet] Maryland: Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, National Cancer Institute; [updated 2016 November 14]. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trotti A, Byhardt R, Stetz J, Gwede C, Corn B, Fu K, et al. Common toxicity criteria: version 2.0. an improved reference for grading the acute effects of cancer treatment: impact on radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:13–47. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, et al. CTCAE v3. 0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–81. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, Armstrong GT, Green DM, Morris EB, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:825–36. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ISCD.org [homepage on the Internet] Connecticutt: International Society for Clinical Densitometry; copyright December 2013 [updated 2014 September 2]. Skeletal Health Assessment in Children from Infancy to Adolescence. Fracture Prediction and Definition of Osteoporosis. Available from: http://www.iscd.org/official-positions/2013-iscd-official-positions-pediatric/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, Whelan S, editors. First Revision [Internet] 3. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/96612/1/9789241548496_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICD-9-CM Diagnosis and Procedure Codes: Abbreviated and Full Code Titles. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CMS.gov [homepage on the Internet] [updated 2014 May 20] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding/ICD9providerdiagnosticcodes/codes.html#. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Rojas T, Bautista FJ, Madero L, Moreno L. The First Step to Integrating Adapted Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events for Children. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2196–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Huang S, Ness KK, Leisenring W, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:946–58. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brignardello E, Felicetti F, Castiglione A, Chiabotto P, Corrias A, Fagioli F, et al. Endocrine health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the need for specialized adult-focused follow-up clinics. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:465–72. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brinkman TM, Krasin MJ, Liu W, Armstrong GT, Ojha RP, Sadighi ZS, et al. Long-Term Neurocognitive Functioning and Social Attainment in Adult Survivors of Pediatric CNS Tumors: Results From the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1358–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Huang S, Ness KK, Clark KL, Green DM, et al. Anterior hypopituitarism in adult survivors of childhood cancers treated with cranial radiotherapy: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:492–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Li C, Armstrong GT, Ness KK, Srivastava DK, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4407–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krull KR, Cheung YT, Liu W, Fellah S, Reddick WE, Brinkman TM, et al. Chemotherapy Pharmacodynamics and Neuroimaging and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2644–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostoufi-Moab S, Seidel K, Leisenring WM, Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Stovall M, et al. Endocrine Abnormalities in Aging Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3240–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuitema I, Deprez S, Van Hecke W, Daams M, Uyttebroeck A, Sunaert S, et al. Accelerated aging, decreased white matter integrity, and associated neuropsychological dysfunction 25 years after pediatric lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3378–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.7050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinkman TM, Li C, Vannatta K, Marchak JG, Lai JS, Prasad PK, et al. Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Symptom Comorbidities and Profiles in Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3417–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atkinson TM, Ryan SJ, Bennett AV, Stover AM, Saracino RM, Rogak LJ, et al. The association between clinician-based common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) and patient-reported outcomes (PRO): a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3669–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Clauser SB, Minasian LM, Dueck AC, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014:106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.