Abstract

Calcium ions (Ca2+) are crucial, ubiquitous, intracellular second messengers required for functional mitochondrial metabolism during uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells. The mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are connected via “mitochondria-associated ER membranes” (MAMs) where ER–mitochondria Ca2+ transfer occurs, impacting the mitochondrial biology related to several aspects of cellular survival, autophagy, metabolism, cell death sensitivity, and metastasis, all cancer hallmarks. Cancer cells appear addicted to these constitutive ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes for their survival, since they drive the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the production of mitochondrial substrates needed for nucleoside synthesis and proper cell cycle progression. In addition to this, the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and mitochondrial Ca2+ have been linked to hypoxia-inducible factor 1α signaling, enabling metastasis and invasion processes, but they can also contribute to cellular senescence induced by oncogenes and replication. Finally, proper ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer seems to be a key event in the cell death response of cancer cells exposed to chemotherapeutics. In this review, we discuss the emerging role of ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes underlying these cancer-related features.

Keywords: cancer; endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes; Ca2+ signaling; inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channels; cell cycle regulation; mitochondrial metabolism; cell death signaling

Mitochondrial Metabolism in Cancer Cell Survival

Cell proliferation requires an increased supply of nutrients, like glucose and glutamine, to achieve a balance between biomass and energy production for making new cells (1). Glucose, the major source of macromolecular precursors and ATP generation, is transformed into pyruvate via the cytosolic process glycolysis. In aerobic conditions, pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria and metabolized to CO2 through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. The TCA cycle is coupled to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which is a pathway for the production of large amounts of ATP. In contrast, in anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is fermented to lactate, a process often referred to as anaerobic glycolysis, which is less energy effective. Nevertheless, proliferative cells exhibit enhanced glycolysis, producing high levels of lactate, even in the presence of O2 (aerobic glycolysis) (2). Cancer cells, which are characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and suppressed apoptosis, tend to switch to aerobic glycolysis despite the presence of sufficient O2 to support the OXPHOS pathway. As such, these cells display an elevated glucose consumption albeit without a proportional increase in its oxidation to CO2 together with an increased lactate production and lactate export, a phenomenon known as “Warburg effect” (3–5). Although glycolysis can produce ATP at a faster rate than OXPHOS (6) and may fuel biosynthesis with intermediates, cancer cells do not rely purely on glycolysis. The reprogrammed cellular metabolism in tumors also maintains sufficient levels of OXPHOS by using pyruvate generated by glycolysis. Indeed, the TCA cycle appears to complement glycolysis, supplying enough ATP, NADH, and biomass precursors for the biosynthesis of other macromolecules, like phospholipids and nucleotides (7). For instance, the TCA cycle intermediate oxaloacetate is used as a substrate for the biosynthesis of uridine monophosphate, a precursor of uridine-5′-triphosphate and cytidine triphosphate involving a rate-limiting step executed by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, which, in turn, catalyzes the de novo synthesis of pyrimidines in the inner mitochondrial membrane (8). Its dehydrogenase activity depends on the electron transport chain (ETC), where it feeds the electrons of the dihydroorotate oxidation to the ETC by reducing respiratory ubiquinone. Thus, adequate ETC activity and proper pyrimidine biosynthesis are intimately linked (8).

Mitochondrial Ca2+ Signals as Regulators of Cell Death and Survival

Ca2+, a cofactor of several rate-limiting TCA enzymes [pyruvate-, isocitrate-, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenases (PDH, IDH, and αKGDH)], plays a pivotal role in the regulation of mitochondrial metabolism and bioenergetics (9). As such, Ca2+ present in the mitochondrial matrix is required for sufficient NADH and ATP production (10).

Transfer of Ca2+ Signals from the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) to the Mitochondria

The accumulation of Ca2+ into the mitochondria strictly depends on the ER, which serves as the main intracellular Ca2+-storage organelle. Ca2+ is stored in the ER by the action of ATP-driven sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) with SERCA2b (11) as the housekeeping isoform and by ER luminal Ca2+-binding proteins like calreticulin and calnexin (12). Ca2+ can be released from the ER via intracellular Ca2+-release channels, including inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs). IP3Rs, which are activated by the second messenger IP3, are ubiquitously expressed in virtually all human cell types (13, 14). IP3 is produced through the hydrolysis of phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate by phospholipase C (PLC)β/γ, an enzyme activated in response to hormones, neurotransmitters, and antibodies. IP3R activity can be suppressed by compounds like xestospongin B (15), which directly inhibits IP3Rs, or U73122, which inhibits PLC activity (16). Although 2-APB (17) and xestospongin C (18) are also used as IP3R inhibitors, these compounds affect other Ca2+-transport systems. For instance, 2-APB is known to inhibit store-operated Ca2+ entry through Orai1 (19) and SERCA (20), and to activate Orai3 channels (19). In addition, similarly to its analogs like DPB162-AE, 2-APB can induce a Ca2+ leak from the ER, partially mediated by ER-localized Orai3 channels (20–23). Xestospongin C also inhibits SERCA with a potency that is equal to its inhibitory action on IP3Rs (24). RyRs are predominantly expressed in excitable cells, including several muscle types, neuronal cells, and pancreatic β cells (25). In most cells, RyRs are mainly activated by cytosolic Ca2+ via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, while in skeletal muscle they are activated through a direct coupling with the dihydropyridine receptor upon depolarization (26). RyR activity can be counteracted by dantrolene (27) and high concentrations of ryanodine (28).

The efficient Ca2+ exchange between the ER and the mitochondria takes place in specialized microdomains, which are established by organellar contact sites and which can be isolated biochemically as mitochondria associated-ER membranes (MAMs) (29–31). Several proteins are involved in ER–mitochondrial tethering, including IP3Rs at the ER side and the Ca2+-permeable channels voltage-dependent anion channel type 1 (VDAC1) at the mitochondrial side (32, 33). The Ca2+ released through IP3Rs and eventually transferred to the mitochondrial intermembrane space by VDAC1 accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU). The functional properties of the MCU are tightly regulated by a growing list of interacting proteins, which enable a tight control over the Ca2+ levels in the mitochondrial matrix (34). These MCU modulators have an important cell physiological impact on mitochondrial metabolism, cell survival, and cell death (35–44).

Seminal work using aequorin targeted to the mitochondria revealed that IP3-evoked Ca2+ signals were efficiently transferred into the mitochondria even when IP3-induced cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) rises were relatively small (45). In contrast, artificial rises in [Ca2+]cyt were ineffective in increasing mitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]mt). This indicated that local [Ca2+]cyt can be very high in the proximity of IP3R channels, which is then sensed by the mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation. These findings were underpinned by perimitochondrial [Ca2+] measurements, showing that the local [Ca2+] was about 20-fold higher than global [Ca2+]cyt, allowing a “quasi-synaptic” transmission of the Ca2+ signal from the ER into the mitochondrial matrix (46). More precise determinations of local [Ca2+] at the ER–mitochondrial contact sites were obtained with pericam-tagged linkers, which indicated concentrations of ~10 µM (47). Importantly, mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer from the ER critically depended on IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, since thapsigargin-induced depletion of the ER, which occurs via ER Ca2+-leak channels that are spread out over the ER membrane, was ineffective in eliciting a [Ca2+]mt rise (46). Efficient IP3R-mediated Ca2+ transfer into the mitochondria is achieved by the molecular chaperone 75-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP75), which physically links IP3Rs to VDAC1 within the MAMs (32). Knockdown of GRP75 impairs the IP3R-mediated Ca2+ transfer to the mitochondria (32).

A positive feedback between the Ca2+ transfer from the ER to the mitochondria and the formation of H2O2 nanodomains at the ER–mitochondrial interface has recently been described (48). These H2O2 nanodomains are formed upon physiological stimulation of the IP3R-mediated Ca2+ transfer to the mitochondria. Ca2+ fuels the ETC, whose functionality determines the production of H2O2. In addition, Ca2+ accumulation in the matrix induced K+ flux, which results in drastically reduced volume of the cristae and subsequent H2O2 flux into the mitochondrial matrix, thereby increasing the mitochondrial matrix volume and squeezing out H2O2-rich fluid at the ER–mitochondrial interface. This locally released H2O2 sensitizes IP3Rs to low concentrations of agonists and stimulates Ca2+ oscillations, thereby further boosting mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Translation of the Ca2+ Signals in the Mitochondria: Cell Survival, Autophagy, or Apoptosis

The adequate transfer of Ca2+ from the ER into the mitochondria requires a proper filling of the ER Ca2+ stores. Also, luminal Ca2+ controls IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release (49). Thus, lowering of the ER Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]ER) will dampen ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer, while increasing [Ca2+]ER will augment ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer. As a consequence, changes in the ER Ca2+-store content will eventually impact the level of Ca2+ transfer from the ER to the mitochondria and thus eventually cell death and survival decisions. A lowering of the ER Ca2+-store content has been shown to serve as a survival mechanism exploited by several pro-survival proteins and oncogenes, including Bax inhibitor-1 (BI-1), antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, and Ras (50–53) as extensively described in Ref. (54). This does not only render cells more resistant to apoptotic triggers but it may also facilitate the survival of damaged or stressed cells, thereby resulting in oncogenesis and cancer cell survival. Several mechanisms can account for this [Ca2+]ER lowering, including the function of BI-1 as an ER Ca2+-leak channel (55) and the sensitization of other ER Ca2+ channels that contribute to the ER Ca2+ leak, like IP3Rs (52, 56).

The decrease in [Ca2+]ER can either induce autophagy due to an impaired basal mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer (10) or suppress autophagy due to diminished [Ca2+]cyt increases (57). On the one hand, low [Ca2+]ER results in decreased spontaneous activity of IP3Rs, thereby abrogating its positive effect on the mitochondrial metabolism and resulting in the activation of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and subsequent increase in autophagic flux (10). Indeed, in many cells, IP3Rs appear to be constitutively active, thereby feeding Ca2+ in the mitochondria, which is necessary for mitochondrial metabolism (Figure 1). This is supported by observations made in DT40 B-lymphocytes in which all three IP3R isoforms have been deleted. These cells display a decreased mitochondrial NADH and ATP production due to a decreased activity of Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases, the F1F0-ATPase, and the ETC (9, 58, 59). The decline in ATP levels results in the activation of AMPK, which inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). In addition to mTOR suppression, AMPK promotes autophagy also through phosphorylation of unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and activation of the ULK1 complex (60, 61). However, the AMPK-dependent induction of autophagy upon inhibition of ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer was shown to be mTOR-independent, suggesting a prominent role for the AMPK–ULK1 axis in this paradigm (10). Of note, while [Ca2+]mt rises appear to suppress autophagy (62), [Ca2+]cyt rises have been implicated in autophagy induction by the activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinaseβ (CaMKKβ), an upstream activator of AMPK. Thus, low [Ca2+]ER can suppress autophagy by diminishing [Ca2+]cyt. It was proposed that antiapoptotic Bcl-2, by lowering the ER Ca2+ levels, could suppress cytosolic Ca2+ signals evoked by various pharmacological and physiological agents, thereby counteracting the activation of CaMKKβ-controlled autophagy (57, 63).

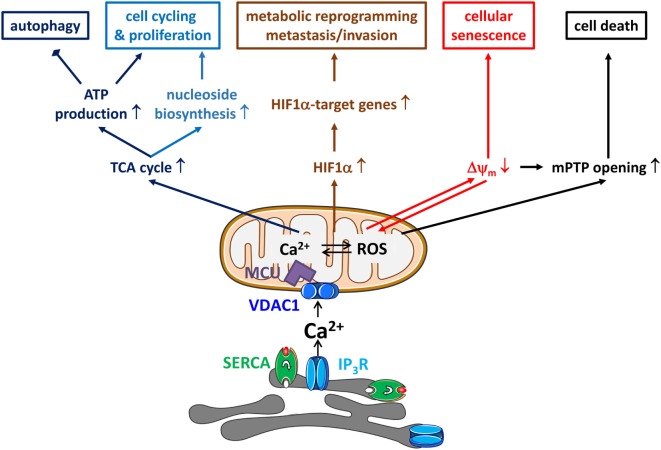

Figure 1.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers in cancer hallmarks. ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers will impact several hallmarks of cancer. First, ER-originating, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-driven Ca2+ signals delivered to the mitochondria will drive the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which will not only result in ATP production via NADH and the electron transport chain but also in the production of mitochondrial substrates shuttled to biosynthetic pathways for macromolecules like nucleosides. This is accompanied by a decrease in autophagic flux due to a low activity of AMP-activated kinase. Second, mitochondrial Ca2+ signals will also increase mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which will drive the transcription of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) regulates breast cancer progression via hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α)—target genes with functions in metabolic reprogramming and, metastasis and invasion. Third, ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes are involved in mediating cellular senescence induced by oncogenes and replication. The mechanism involves the partial depolarization of the mitochondrial potential (Δψm) and accumulation of ROS. Fourth, ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes impact cellular sensitivity toward apoptotic stimuli. In particular, mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, together with the accompanying ROS production, has been a critical factor for mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. Thus, the cell death-inducing properties of several chemotherapeutics actually critically depend on their ability to elicit mitochondrial Ca2+ overload. Thus, ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers display both oncogenic properties (cell cycling, proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, metastasis, and invasion) and tumor suppressive properties (reduced autophagy and increased cell death sensitivity).

Further complexity of autophagy regulation arises from the fact that IP3R sensitization by accessory proteins might have an opposite outcome on autophagy, dependent on whether the sensitization is limited to MAMs or whether it occurs all over the ER membrane. Indeed, IP3R sensitization in the MAMs would lead to increased basal mitochondrial Ca2+ delivery, driving ATP production and thus suppressing autophagy. For example, Bcl-XL, which is present in the MAMs, can augment mitochondrial metabolism and is able to reduce autophagy by local IP3R sensitization in the MAMs (64, 65) (Table 1). In contrast, IP3R sensitization outside the MAMs will affect the overall ER Ca2+ loading due to an increased ER Ca2+ leak through IP3Rs that become sensitive to basal IP3 levels. This would result in partially depleted ER Ca2+ stores and decreased basal mitochondrial Ca2+ delivery, leading to reduced ATP production and increased autophagy. For example, BI-1, which presumably is ubiquitously present in the ER membrane, reduces the steady-state ER Ca2+ levels through IP3R sensitization, decreasing mitochondrial bioenergetics and thus inducing autophagy (66).

Table 1.

The impact of experimental, physiological, and cancer-related modulators of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–mitochondrial Ca2+ flux on cell death, survival, and migration.

| Protein | Modulator | Mechanism | ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ flux | Cellular/in vivo effect | Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP3R | IP3R1/IP3R3 knockdown | IP3R1/IP3R3 expression ↓ | ↓ | Cell death ↑ caused by mitotic catastrophe | HrasG12V-cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) transformed human fibroblasts, tumorigenic cell lines: breast, prostate, and cervix | (67) |

| XeB | Selective IP3R inhibitor | Autophagy ↑ as a cell survival mechanism | Primary fibroblasts; non-tumorigenic breast and prostate cell lines | |||

| U73122 | PLC inhibitor (IP3↓) | Tumor size and weight ↓ | B16F10 melanoma cell tumor xenograft (only performed with XeB) | |||

| IP3R2/IP3R3 knockdown | IP3R2/IP3R3 expression ↓ | ↓ | Cell death ↑ caused by excessive autophagy | Breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) | (68) | |

| XeCa/2-APBb | Non-selective IP3R inhibitors | Tumor volume and weight ↓ | Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model (only performed with 2-APB) | |||

| IP3R2 knockdown | IP3R2 expression ↓ | ↓ | Escape from oncogene-induced senescence | Immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (HECs) | (69) | |

| BI-1 | (Direct) sensitization of IP3Rs | ↓ | Autophagy ↑ | HeLa and MEF cells | (56, 66) | |

| Functioning as an ER Ca2+-leak channel, mainly outside the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) | (55) | |||||

| Bcl-XL | Direct sensitization of IP3Rs (at the MAMs), promoting pro-survival Ca2+ oscillations | ↑ | Cellular bioenergetics ↑ | Reconstituted DT40-triple IP3R knockout cells | (64, 65, 70) | |

| Apoptosis ↓ | CHO cells | |||||

| PML | Counteracting Akt-mediated IP3R3 phosphorylation through PP2A recruitment | ↑ | Apoptosis ↑ | MEF cells | (71, 72) | |

| Autophagy ↓ | H1299 | |||||

| APL NB4 cells | ||||||

| Bcl-2 | Direct inhibition of IP3Rs | ↓ | Apoptosis ↓ | WEHI7.2 cells and Jurkat | (54, 73, 74) | |

| H2O2 | Direct sensitization of IP3Rs (at the MAMs), via oxidation of specific thiol group of IP3R | ↑ | Cellular bioenergetics ↑ | HEPG2 | (48) | |

| SERCA | TMX1 | Binds and inhibits SERCA2b (at the MAMs) in a calnexin-dependent manner | ↑ | Apoptosis ↓ | A375P melanoma and HeLa cell (xenograft) | (75, 76) |

| Tumor growth ↓ | ||||||

| p53 (extranuclear) | Accumulates at the ER and MAMs upon chemotherapy treatment, directly binding and activating SERCA2b by changing its oxidative state | ↑ | Apoptosis ↑ | MEF, HeLa, and H1299 (human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line) | (77, 78) | |

| HCT-116 and MDA-MB 468 | ||||||

| Resveratrol | Reduced SERCA activity due to inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthase | ↑ | Apoptosis ↑ | Endothelial/epithelial cancer cell hybrid EA.hy926, HeLa | (79) | |

| VDAC | Mcl-1 | Binds and activates voltage-dependent anion channel type 1 (VDAC1) and VDAC3 | ↑ | Cell migration ↑ caused by mitochondrial ROS ↑ | NSCLC cell lines | (80) |

| MCU | MCU knockdown | MCU expression ↓ | ↓ | Metastatic cell motility and matrix invasiveness ↓ caused by decreased mitochondrial ROS and HIF1-mediated transcription | Triple-negative breast cancers | (81) |

| MDA-MB-231 xenografts | ||||||

| Cell death ↑ caused by mitotic catastrophe | HrasG12V-CDK4 transformed human fibroblasts; tumorigenic breast, prostate, and cervix (HeLa) cancer cell lines | (67) | ||||

| FATE1 | Uncoupling of ER and mitochondria | ↓ | Apoptosis ↓ | Adrenocortical carcinoma cells | (82) | |

aSarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor.

bStore-operated Ca2+ entry and SERCA inhibitor.

In contrast to the reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ supply, which triggers autophagy, it has become clear that excessive Ca2+ transfer from the ER to the mitochondria results in cell death (83–85) (Figure 1). This involves the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) in the inner mitochondrial membrane, resulting in mitochondrial swelling and mitochondrial membrane rupture, eventually leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis, if sufficient levels of ATP are available (85). Many cell death-inducing agents, like H2O2 (86, 87), arachidonic acid (88), ceramide (50, 86), and menadione (89, 90) have been shown to act at the ER by triggering Ca2+ release through IP3Rs and subsequently provoking mitochondrial Ca2+ rises (91). Moreover, the ability of chemotherapeutics, like adriamycin (77), arsenic trioxide (71), and mitotane (82) and of photodynamic therapy (78) to kill cancer cells strongly depends on their ability to adequately induce ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer (92). The spectrum of chemotherapeutics acting in this way might be quite broad, since recently it was shown that cisplatin and topotecan increase [Ca2+]cyt over time, although [Ca2+]mt was not determined (93). The transfer of pro-apoptotic Ca2+ signals to the mitochondria appears to be mediated by VDAC1 and not VDAC2 or VDAC3 (86). Also further insights in the mechanism underlying mPTP opening upon mitochondrial Ca2+ overload have been obtained. Ca2+ accumulating in the mitochondrial matrix binds to cardiolipin, which dissociates from the respiratory chain complex II and eventually results in its disassembly. The unleashed subunits of complex II produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondrial matrix, resulting in the opening of the mPTP (94).

The dichotomous impact of mitochondrial Ca2+ on both apoptosis and autophagy implies that reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer will simultaneously result in acquired resistance to apoptotic stimuli and in increased autophagy (Figure 1) (95). This mechanism has been shown to be responsible for the sustained proliferation of cells deficient in promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), a tumor suppressor present at the MAMs that augments ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ flux on the one hand and excessive chemotherapeutic resistance on the other hand (71, 72). Indeed, loss of PML reduced basal ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers, thereby inducing sustained autophagy, promoting malignant cell survival and reduced chemotherapy-induced apoptosis contributing to poor chemotherapeutic efficacy (Table 1).

Finally, it is important to remark that cell death and survival are regulated by mitochondrial dynamics, including mitochondrial fusion, mainly mediated by optic atrophy 1 and by dynamin-related GTPases mitofusin-1 (Mfn-1) and Mfn-2, and mitochondrial fission, mainly mediated by the cytosolic soluble dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) (96, 97). Mitochondrial fragmentation leads to Bax-dependent apoptosis, while hyperfusion of mitochondria in response to a decline in Drp1 results in proliferation. Moreover, mitochondrial dynamics themselves are also regulated by Ca2+ signaling via calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation of Drp1 (98). Mitochondrial hyperfusion may also render cells more sensitive to apoptotic stimuli due to hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane and thus an increased driving force for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (99, 100). Hyperpolarization of mitochondrial membrane is also tightly connected to ROS production and release. As such, extensive ROS generation results in hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane, followed by amplified ROS generation. ROS are released into the cytosol, where they can affect other mitochondria. This process is called ROS-induced ROS release and it could play important role in mitochondrial and cellular injuries (101).

Cancer Cells’ Addiction to Constitutive ER–Mitochondrial Ca2+ Signaling

Clearly, basal IP3R-driven Ca2+ signals and subsequent ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer impact cell death and survival processes. Inhibition of IP3Rs and thus spontaneous Ca2+ signals lead to reduced mitochondrial bioenergetics and increased autophagy, allowing cell survival (10). Recently, the role of basal IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling and ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer for cancer cell survival was investigated in more detail (67). A comparison was made between non-tumorigenic and tumorigenic cell lines, as well as between non-transformed primary human fibroblasts and fibroblasts transformed by the ectopic expression of oncogenic HRasG12V and cyclin-dependent kinase 4. For reasons of clarity, we will refer to the former as “normal cells” and to the latter as “cancer cells.” Strikingly, inhibition of IP3R activity, knockdown of IP3R or MCU led in both normal and cancer cells to a so-called “bioenergetic crisis” characterized by a decreased basal and maximal oxygen consumption rate and increased AMPK phosphorylation, subsequently resulting in an increased autophagic flux. However, these interventions resulted in cell death in the cancer cells but not in the normal cells, indicating that autophagy upregulation induced upon IP3R inhibition was sufficient to sustain cell survival in the normal cells but not in cancer cells (67). Similar results were obtained in another recent study, which also implicated autophagy induced by IP3R inhibition in cancer cell death (68). Selective knockdown of IP3R isoforms using siRNA or general IP3R inhibition using 2-APB or xestospongin C compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics, led to generation of ROS, activation of AMPK, and upregulation of Atg5, an essential autophagy gene. This resulted in excessive autophagy in the cancer cells. Cells could be rescued by ROS scavengers and autophagy inhibitors, indicating that autophagy was at least in part responsible for the cell death. 2-APB was also used in xenograft models, where it strongly suppressed in vivo tumor growth. It is important to note that 2-APB and xestospongin C cannot be considered as selective inhibitors of IP3Rs and thus their impact on cancer cell survival might be related to off-target effects (Table 1).

However, the fact that in some conditions autophagy upregulation is not sufficient for cancer cell survival upon IP3R inhibition is in striking contrast to the important role of autophagy for cancer cell survival in conditions of nutrient starvation (102). Ras-driven lung cancer cells were dependent on autophagy for their survival during starvation conditions. Consistent with this, caloric restriction was more effective to suppress Ras-driven tumor growth when it was combined with autophagy inhibition (103). This may indicate that the contribution of autophagy for cancer cell survival might be different dependent on the way autophagy was induced (IP3R inhibition versus starvation), which may be due to differences in the produced breakdown products and their usage in metabolic and biosynthetic pathways (104). The cancer cell death induced by IP3R inhibition could be rescued by providing the cells with cell-permeable mitochondrial substrates like methyl pyruvate, that is oxidized to NADH necessary to drive OXPHOS and production of ATP or dimethyl α-ketoglutarate, a precursor for glutamine to fuel the TCA cycle, where it enters and is oxidized by a Ca2+-dependent α-KGDH as the first step (67). Moreover, the protective effects of the substrates in xestospongin B-treated cancer cells were unrelated to their antioxidant properties, since the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine could not protect the cancer cells against cell death. Instead, nucleoside complementation could rescue the death of the cancer cells induced by IP3R inhibition (67), indicating that constitutive ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes are required for cancer cell survival by sustaining an adequate source of mitochondrial substrates for nucleotide synthesis. This phenomenon was also observed in vivo, where tumor growth could be reduced upon treatment with xestospongin B.

Indeed, in conditions of suppressed ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ flux, normal cells display slower cell-cycle progression and become arrested at the G1/S checkpoint. This prevents DNA synthesis and shifts cells to accumulate in the G1 phase rather than the S phase (Figure 2), ultimately reducing the rate of daughter cell generation and proliferation. Conversely, cancer cells exposed to IP3R inhibitors have lost proper control over their G1/S checkpoint, progressing through the cell cycle and undergoing mitosis irrespective of their OXPHOS and mitochondrial bioenergetic status. As such, cancer cells will divide even though their mitochondrial metabolism is insufficient to cope with the anabolic pathways needed to make a living daughter cell, eventually resulting in a “mitotic catastrophe” upon daughter cell separation (67). Interestingly, arresting cancer cells in the G1/S phase and preventing them to undergo mitosis strongly suppressed cell death induced by IP3R inhibition. Hence, beyond the well-established roles of IP3Rs in apoptosis, these data reveal that, in the absence of proper cell-cycle control, cells are addicted to constitutive IP3R function and sustained ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer for fueling mitochondrial metabolism. These ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes maintain sufficiently high levels of TCA cycling by ensuring the activity of Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases, thereby delivering an adequate supply of mitochondrial substrates required for nucleotide production and DNA synthesis during ongoing proliferation (67).

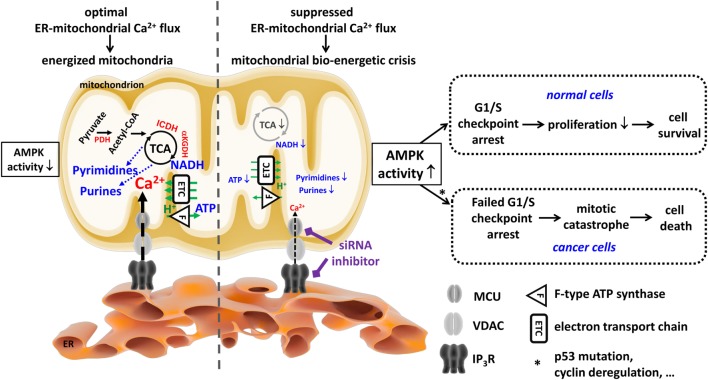

Figure 2.

Cancer cells are addicted to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes to produce tricarboxylic acid (TCA)-dependent mitochondrial substrates used to sustain their uncontrolled proliferation. In both non-malignant and malignant cells, mitochondria require Ca2+ from the ER Ca2+ store for an adequate performance of the TCA cycle, which ultimately leads to energy production (ATP), redox homeostasis (NADH), and anabolism, e.g., of pyrimidine and purine nucleotides. The Ca2+-dependent control of the TCA cycle is due to the Ca2+-dependent activity of several rate-limiting enzymes (PDH, ICDH, and αKGDH, all indicated in red). Ca2+ is efficiently delivered to the mitochondria in a quasi-synaptic manner involving Ca2+-signaling microdomains established at mitochondria-associated ER membranes involving inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), voltage-dependent anion channel type 1 (VDAC1), and mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) as Ca2+-transport systems. Of note, although cancer cells switch to glycolysis for their ATP production, they too rely on functional mitochondria for the production of mitochondrial substrates used for anabolic processes, like the generation of nucleotides required for the DNA synthesis necessary for their deregulated cell cycle progression and proliferation. Ablation of these ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes (e.g., by using siRNA-based approaches or pharmacological inhibitors like xestospongin B) results in compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics, causing a decline in ATP, NADH, and nucleotides. In both non-malignant and malignant cells, this leads to an increase in AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) activity. However, in non-malignant cells, increased AMPK activity will result in an arrest at the G1/S checkpoint, likely involving p53 activation and cyclin E downregulation, which will dampen proliferation as a cell survival strategy. In malignant cells, the link between AMPK activity and the G1/S checkpoint is lost (e.g., due to p53 mutations or cyclin deregulation). As a consequence, despite the mitochondrial bioenergetic crisis and the lack of mitochondrial substrates for DNA synthesis, cancer cells will progress toward the S phase and mitosis. This results in necrotic cell death due to mitotic catastrophe. This figure was originally published in Ref. (105). © 2016 Geert Bultynck. A copyright license to republish this figure has been obtained.

Interestingly, the need for adequate mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling in tumor cells is further supported by a very recent study performed in triple-negative breast cancer (81). It was shown that MCU expression positively correlated with the metastatic phenotype and clinical stage of the breast cancers, while the expression of MCUb, a negative regulator of MCU (37), displayed a negative correlation. Strikingly, silencing of MCU blunted cell invasiveness without affecting cell viability. The in vivo growth of breast cancer cells in which MCU was deleted was severely impaired, correlating with an altered cellular redox state and impaired mitochondrial production of ATP. In this mechanism, MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake in the mitochondria resulted in increased ROS production and activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α signaling, contributing to tumor growth and metastatic behavior (81). Similar results were reported in NSCLS cells where mitochondrial ROS generation and increased cell migration were correlating to enhanced [Ca2+]mt uptake through Mcl-1/VDAC interaction (80) (Table 1).

Further studies are necessary in order to determine how cancer cells escape from the G1/S checkpoint with impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics due to reduced ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes. However, an important link between mitochondrial dynamics and cell-cycle control was described (106). This study revealed that at the G1/S checkpoint the mitochondrial structure changes into a single tubular network, electrically coupled and hyperpolarized, boosting ATP production (Figure 3) (106). The progression of the cell cycle is ensured by specific cyclins associated with CDKs (107). The G1-to-S transition, which ensures the initiation of DNA replication, is controlled by cyclin E, which, in turn, further binds and activates CDK2 to phosphorylate downstream targets for DNA production. Cyclin E abundance is restricted to the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase and decreases with the progression of the cell cycle. Mitochondrial hyperfusion will support ATP production and as such cyclin E stability, enabling S-phase progression. This actually establishes an important “mitochondrial checkpoint” that only permits G1/S progression when mitochondrial bioenergetics and cellular health are adequate (Figure 2). Based on the model proposed by Finkel and Hwang (108), cells with impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics and, thus reduced ATP output and increased AMPK activity, will activate p53 and p21, a cell cycle regulator, leading to a drop in cyclin E (109) and an arrest of the cells at the G1 phase due to their inability to overcome the G1/S checkpoint (Figure 3). In light of the requirement for a burst of ATP production for proper S phase progression, an increased mitochondrial Ca2+ demand would also be expected. Therefore, further work is required to establish whether IP3R activity and ER–mitochondrial tethering and/or Ca2+ transfers could become enhanced at the G1/S transition to support this increased ATP production as part of the “mitochondrial checkpoint.” Previous studies have implicated IP3R sensitization as a critical step during G1/S transition and identified IP3Rs as targets for cyclins and substrates for CDKs (110). However, in cancer cells, the G1/S checkpoint control appears to be lost despite the fact that IP3R inhibition still leads to activation of AMPK, implying defects in the mechanisms linking AMPK to the G1/S checkpoint arrest, for example, mutations impairing p53 activity or hyperactivating CDKs. Previous work indicated that p53 mutations could result in a bypass of G1/S arrest (108). Thus, re-expression of p53 may restore the G1/S checkpoint control in a number of these cancer cell types exposed to IP3R inhibition, thereby slowing down cell cycle progression and proliferation and preventing cell death by mitotic catastrophe.

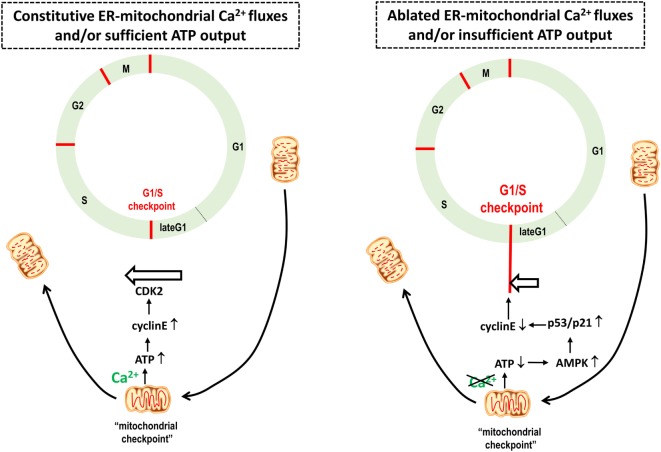

Figure 3.

A boost in mitochondrial ATP output provides a mitochondrial checkpoint for cellular health, enabling cells to bypass the G1/S checkpoint and cell cycle progression. Based on Mitra et al. (106), mitochondrial structure changes along the cell cycle progression. At the late G1 phase, the mitochondrial structure changes into a giant, single tubular network, electrically coupled and hyperpolarized, boosting ATP production. The G1–S transition that ensures the initiation of DNA replication is controlled by the cyclin E, which, in turn, further binds and activates CDK2. Cyclin E is upregulated upon increased ATP output, enabling S-phase progression and proliferation. Non-tumorigenic cells experiencing a reduction of ATP production due to compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics will trigger the G1/S checkpoint arrest due to AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) activation and subsequent phosphorylation and activation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 that in turn downregulates cyclin E protein levels. In tumorigenic cells, it is anticipated that this tight link between adequate mitochondrial bioenergetics and the G1/S checkpoint is lost. Hence, cancer cells can progress through the cell cycle irrespective of their mitochondrial bioenergetic status. Thus, a mitochondrial bioenergetic crisis will slow down the cell cycle and proliferation in normal cells, while in cancer cells, the cell cycle will continue, eventually resulting in a mitotic catastrophe.

In addition to the addiction of some cancer cells to constitutive ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes, ER–mitochondrial contact sites and Ca2+-signaling events might be altered to favor cancer cell survival. This concept is supported by another recent study. TMX1, a redox-sensitive oxidoreductase that is enriched in the MAMs in a palmitoylation-dependent manner, was shown to regulate mitochondrial bioenergetics and in vivo tumor growth by controlling ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling (75, 76). Upon palmitoylation, TMX1 is recruited to the MAMs, where it binds and inhibits SERCA2b. As such, loss of TMX1 accelerates SERCA2b-mediated ER Ca2+ accumulation, particularly in the MAMs. As a consequence, loss of TMX1 in HeLa and A375P, a malignant melanoma cell line, increased ER Ca2+ retention and reduced ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer. This led to a reduction in mitochondrial bioenergetics, thereby lowering ATP production and the oxygen consumption rate. Consistent with the work of Foskett and others (67), loss of TMX1 resulted in increased cell death and increased ROS production in vitro (Table 1). However, in vivo, opposite findings were obtained. Furthermore, while loss of TMX1 in these cancer cell lines accelerated tumor growth, TMX1 overexpression had the opposite effect (75). This might be due to the contribution of the microenvironment, including reduced accessibility of oxygen and nutrients, which may contribute to mitochondrial stress. Interestingly, it was shown that although cancer cells lacking TMX1 proliferate slower and display more spontaneous cell death, they are more resistant to mitochondrial stress inducers like rotenone and antimycin (75). Hence, in vivo, cancer cells may experience ongoing mitochondrial stress and/or shortage of nutrients. Under such conditions, cancer cells that have lost TMX1 expression might have a growth advantage over cancer cells with high TMX1 expression. Alternatively, these cells may display increased autophagy, which is beneficial for cancer cell survival under starvation conditions by providing mitochondrial substrates that feed the TCA cycle and sustain nucleotide biosynthesis (102, 104). However, further work is needed to understand these aspects in more detail. In particular, the differences between IP3R inhibition and loss of TMX1,which both impair mitochondrial bioenergetics and result in spontaneous cell death in vitro but lead to an opposite effect in in vivo tumor growth experiments (impaired upon IP3R inhibition versus accelerated upon TMX1 loss) require further research.

ER–Mitochondrial Ca2+ Signaling Underlying Cellular Senescence and Cancer Cell Death Therapies

It is important to note that alterations in ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers will not only impact mitochondrial bioenergetics but also cancer cell senescence and sensitivity toward chemotherapeutic drugs (Figure 1).

Adequate ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer has been implicated in oncogene-induced and replicative senescence, a condition characterized by a stable proliferation arrest (69, 111). Cancer cells in which IP3R2, the most sensitive isoform to its ligand IP3, or MCU were knocked down could escape cellular senescence (69). Conversely, cancer cells exposed to a continuous supply of cell-permeable IP3 displayed premature senescence. Strikingly, cells undergoing oncogene-induced senescence displayed an increase in basal mitochondrial Ca2+ and IP3-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation. Cells lacking IP3R2 or MCU did not display this mitochondrial Ca2+ rise. Mitochondrial Ca2+ induced cellular senescence by causing a partial depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane and an accumulation of mitochondrial ROS. Moreover, cellular senescence could be mimicked by mitochondrial depolarization by the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (69). A further detailed discussion on the alterations in mitochondrial homeostasis and the contributing underlying mechanisms in cellular senescence is provided elsewhere (112).

The adequate ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer underlies the cell death-inducing properties of several chemotherapeutic drugs. Recently, extranuclear p53 has emerged as an important molecular link between chemotherapeutic responses and Ca2+ signaling (77, 113). Upon exposure to chemotherapeutic drugs, p53 was shown to accumulate at the ER membranes where it increases SERCA2b activity (Table 1). This resulted in increased [Ca2+]ER, increasing the likelihood of pro-apoptotic Ca2+ transfers to the mitochondria. Cells that lack p53 or that express oncogenic p53 mutations failed to upregulate SERCA2b activity and display ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers and cell death (72). In addition, cells that lack p53 can be sensitized to chemotherapy by overexpressing SERCA or MCU, facilitating ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer (78). Thus, downregulation of ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes may not only favor cancer cell survival (e.g., by upregulating autophagy) but could also lead to cell-death resistance, as has been shown recently for tumor cells lacking PML (71) or FATE1 (82). FATE1 is a cancer-testis antigen, which localizes at the ER–mitochondrial interface (82). Recently, it has been identified as an MAMs spacer, thereby impairing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. As a consequence, FATE1 upregulation, like in adrenocortical carcinoma cells, results in cell-death resistance not only in response to pro-apoptotic stimuli that impinge on ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling but also in response to mitotane, a chemotherapeutic drug clinically used in the treatment of patients with adrenocortical cancer. Moreover, FATE1 expression is also inversely correlated with the overall survival of adrenocortical cancer patients (82). Oppositely, enhancing ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer will favor cell-death therapies (92). Interestingly, some anticancer drugs might actually impact ER–mitochondrial contact sites and thereby enhance the response to other chemotherapeutics. For instance, ABT-737, a non-selective Bcl-2/Bcl-XL inhibitor (114, 115) could reverse the cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells due to increased ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ contact sites (116). Specifically, the authors demonstrated that ABT-737 enriched cisplatin-induced GRP75 and Mfn-2 content at the ER–mitochondria interface. The latter event led to enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and subsequent cell death (116). Moreover, tumor suppressors at MAMs, including p53, were reported to modulate Ca2+ transfer and the contact sites (54). Another anticancer compound, whose mechanism involves a Ca2+-dependent step is resveratrol (79). This natural compound selectively increased the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake of cancer cells, while normal cells remained unaffected. Similarly to other phenols, resveratrol inhibits ATP synthase and impairs ATP production, thereby decreasing mitochondrial [ATP] without affecting cytosolic [ATP] (117). This resulted in suppressed SERCA activity, particularly at the MAM interface, thereby increasing the net flux of Ca2+ through IP3Rs and augmenting mitochondrial uptake (Table 1). The striking difference between the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in cancer and in normal cells in the presence of resveratrol was attributed to the enhanced and more stable MAMs in cancer cells, which facilitate the ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer (79). In addition to this, resveratrol can induce autophagy via a mechanism that requires cytosolic Ca2+ and the presence of IP3Rs. In this study, resveratrol triggered a depletion of the ER in intact cells independently of IP3Rs, but not in permeabilized cells where Ca2+ stores are loaded by application of ATP, arguing against a direct inhibition of SERCA by resveratrol. Thus, these findings may relate to an in cellulo decline in SERCA activity due to a decline in ATP (118).

Conclusion

Endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes impact several cancer hallmarks, including mitochondrial metabolism, autophagy, apoptosis resistance, and metastasis. It is very likely that different tumor stages require different levels of ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ flux for instance to ensure cell survival at early stages, promote invasion at intermediate stages and tumor growth at late stages. Moreover, different oncogenes and tumor suppressors exert their part of their function at the MAMs by impacting Ca2+-transport systems.

An emerging concept is that cancer cells become addicted to constitutive ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers. Thus, suppressing these basal ongoing ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes represent a therapeutic strategy to target tumor cells thereby suppressing their survival, invasion and growth.

In contrast to this, ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes appear instrumental for proper therapeutic responses to chemotherapeutic drugs, since an adequate ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer is important for their cell death-inducing properties. Hence, enhancing ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfer may provide an attractive strategy to overcome cell death resistance of certain types of cancer toward chemotherapeutics.

Hence, it is expected that both dampening and boosting ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ transfers hold therapeutic potential, dependent on the clinical stage of the tumor and the applied anticancer strategy. However, a major challenge will be to limit these effects to cancer cells, as obviously ER–mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes also underlie the survival of healthy cells. Nevertheless, the presence, composition, and properties of ER–mitochondrial contact sites in healthy versus cancer cells and the dependence of these cells on these sites for cell survival may be strikingly different, creating a therapeutic window for the selective targeting of cancer cells while sparing healthy cells.

Author Contributions

GB and RR drafted the manuscript. HI, MK, RR, and GB wrote parts of the manuscripts. HI, RR, and GB prepared figures. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer, IS, and handling editor declared their shared affiliation, and the handling editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

Research performed in the authors’ laboratory was supported by grants from the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO grants 6.057.12, G.0819.13, G.0C91.14, and G.0A34.16), by the Research Council of the KU Leuven (OT/14/101) and by the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Program (Belgian Science Policy; IAP/P7/13). GB is member of the FWO-research network WO.019.17N. HI and MK are holders of an FWO doctoral fellowship. The authors thank all lab members, including Jan B. Parys and Humbert De Smedt, and Dr. Paolo Pinton (University of Ferrara, Italy) for fruitful discussions.

References

- 1.Greiner EF, Guppy M, Brand K. Glucose is essential for proliferation and the glycolytic enzyme induction that provokes a transition to glycolytic energy production. J Biol Chem (1994) 269:31484–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (2011) 27:441–64. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol (1927) 8:519–30. 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson KA, Schell JC, Rutter J. Pyruvate and metabolic flexibility: illuminating a path toward selective cancer therapies. Trends Biochem Sci (2016) 41:219–30. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci (2016) 41:211–8. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeiffer T, Schuster S, Bonhoeffer S. Cooperation and competition in the evolution of ATP-producing pathways. Science (2001) 292:504–7. 10.1126/science.1058079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boroughs LK, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol (2015) 17:351–9. 10.1038/ncb3124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desler C, Lykke A, Rasmussen LJ. The effect of mitochondrial dysfunction on cytosolic nucleotide metabolism. J Nucleic Acids (2010) 2010:701518. 10.4061/2010/701518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2012) 13:566–78. 10.1038/nrm3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cárdenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgó J, Müller M, et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell (2010) 142:270–83. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLennan DH, Rice WJ, Green NM. The mechanism of Ca2+ transport by sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases. J Biol Chem (1997) 272:28815–8. 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalak M, Robert Parker JM, Opas M. Ca2+ signaling and calcium binding chaperones of the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium (2002) 32:269–78. 10.1016/S0143416002001884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikoshiba K. Role of IP3 receptor signaling in cell functions and diseases. Adv Biol Regul (2015) 57:217–27. 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1793:933–40. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaimovich E, Mattei C, Liberona JL, Cardenas C, Estrada M, Barbier J, et al. Xestospongin B, a competitive inhibitor of IP3-mediated Ca2+ signalling in cultured rat myotubes, isolated myonuclei, and neuroblastoma (NG108-15) cells. FEBS Lett (2005) 579:2051–7. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacMillan D, McCarron J. The phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 inhibits Ca2+ release from the intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store by inhibiting Ca2+ pumps in smooth muscle: U-73122 inhibits intracellular Ca2+ release. Br J Pharmacol (2010) 160:1295–301. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00771.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. J Biochem (1997) 122:498–505. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gafni J, Munsch JA, Lam TH, Catlin MC, Costa LG, Molinski TF, et al. Xestospongins: potent membrane permeable blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron (1997) 19:723–33. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW. Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate on store-operated calcium entry. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:19265–73. 10.1074/jbc.M801535200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Missiaen L, Callewaert G, De Smedt H, Parys JB. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate affects the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, the intracellular Ca2+ pump and the non-specific Ca2+ leak from the non-mitochondrial Ca2+ stores in permeabilized A7r5 cells. Cell Calcium (2001) 29:111–6. 10.1054/ceca.2000.0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittremieux M, Gerasimenko JV, Schuermans M, Luyten T, Stapleton E, Alzayady KJ, et al. DPB162-AE, an inhibitor of store-operated Ca2+ entry, can deplete the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store. Cell Calcium (2017) 62:60–70. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon-Aparicio D, Pacheco J, Chavez-Reyes J, Galindo JM, Valdes J, Vaca L, et al. Orai3 channel is the 2-APB-induced endoplasmic reticulum calcium leak. Cell Calcium (2017). 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leon-Aparicio D, Chavez-Reyes J, Guerrero-Hernandez A. Activation of endoplasmic reticulum calcium leak by 2-APB depends on the luminal calcium concentration. Cell Calcium (2017). 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Smet P, Parys JB, Callewaert G, Weidema AF, Hill E, De Smedt H, et al. Xestospongin C is an equally potent inhibitor of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and the endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+ pumps. Cell Calcium (1999) 26:9–13. 10.1054/ceca.1999.0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fill M, Copello JA. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev (2002) 82:893–922. 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Protasi F. Structural interaction between RYRs and DHPRs in calcium release units of cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr (2002) 7:d650–8. 10.2741/A801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao F, Li P, Chen SR, Louis CF, Fruen BR. Dantrolene inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels. Molecular mechanism and isoform selectivity. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:13810–6. 10.1074/jbc.M006104200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meissner G. Ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels and their regulation by endogenous effectors. Annu Rev Physiol (1994) 56:485–508. 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieckowski MR, Giorgi C, Lebiedzinska M, Duszynski J, Pinton P. Isolation of mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nat Protoc (2009) 4:1582–90. 10.1038/nprot.2009.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raturi A, Simmen T. Where the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondrion tie the knot: the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM). Biochim Biophys Acta (2013) 1833:213–24. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giorgi C, Missiroli S, Patergnani S, Duszynski J, Wieckowski MR, Pinton P. Mitochondria-associated membranes: composition, molecular mechanisms, and physiopathological implications. Antioxid Redox Signal (2015) 22:995–1019. 10.1089/ars.2014.6223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Várnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol (2006) 175:901–11. 10.1083/jcb.200608073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchi S, Patergnani S, Pinton P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection: one touch, multiple functions. Biochim Biophys Acta (2014) 1837:461–9. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foskett JK, Philipson B. The mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter complex. J Mol Cell Cardiol (2015) 78:3–8. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallilankaraman K, Doonan P, Cárdenas C, Chandramoorthy HC, Müller M, Miller R, et al. MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell (2012) 151:630–44. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallilankaraman K, Cárdenas C, Doonan PJ, Chandramoorthy HC, Irrinki KM, Golenár T, et al. MCUR1 is an essential component of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol (2012) 14:1336–43. 10.1038/ncb2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raffaello A, De Stefani D, Sabbadin D, Teardo E, Merli G, Picard A, et al. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a multimer that can include a dominant-negative pore-forming subunit. EMBO J (2013) 32:2362–76. 10.1038/emboj.2013.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman NE, Chandramoorthy HC, Shanmughapriya S, Zhang XQ, Vallem S, Doonan PJ, et al. SLC25A23 augments mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, interacts with MCU, and induces oxidative stress-mediated cell death. Mol Biol Cell (2014) 25:936–47. 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patron M, Checchetto V, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Vecellio Reane D, Mantoan M, et al. MICU1 and MICU2 finely tune the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter by exerting opposite effects on MCU activity. Mol Cell (2014) 53:726–37. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doonan PJ, Chandramoorthy HC, Hoffman NE, Zhang X, Cárdenas C, Shanmughapriya S, et al. LETM1-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ flux modulates cellular bioenergetics and proliferation. FASEB J (2014) 28:4936–49. 10.1096/fj.14-256453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vais H, Tanis JE, Müller M, Payne R, Mallilankaraman K, Foskett JK. MCUR1, CCDC90A, is a regulator of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Cell Metab (2015) 22:533–5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vais H, Mallilankaraman K, Mak D-OD, Hoff H, Payne R, Tanis JE, et al. EMRE is a matrix Ca2+ sensor that governs gatekeeping of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Cell Rep (2016) 14:403–10. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antony AN, Paillard M, Moffat C, Juskeviciute E, Correnti J, Bolon B, et al. MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake dictates survival and tissue regeneration. Nat Commun (2016) 7:10955. 10.1038/ncomms10955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomar D, Dong Z, Shanmughapriya S, Koch DA, Thomas T, Hoffman NE, et al. MCUR1 is a scaffold factor for the MCU complex function and promotes mitochondrial bioenergetics. Cell Rep (2016) 15:1673–85. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science (1993) 262:744–7. 10.1126/science.8235595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Csordás G, Thomas AP, Hajnóczky G. Quasi-synaptic calcium signal transmission between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. EMBO J (1999) 18:96–108. 10.1093/emboj/18.1.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Csordás G, Várnai P, Golenár T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, et al. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell (2010) 39:121–32. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Booth DM, Enyedi B, Geiszt M, Várnai P, Hajnóczky G. Redox nanodomains are induced by and control calcium signaling at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell (2016) 63:240–8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Droogmans G, Casteels R. Ca2+ release induced by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate is a steady-state phenomenon controlled by luminal Ca2+ in permeabilized cells. Nature (1992) 357:599–602. 10.1038/357599a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinton P, Ferrari D, Rapizzi E, Di Virgilio F, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. The Ca2+ concentration of the endoplasmic reticulum is a key determinant of ceramide-induced apoptosis: significance for the molecular mechanism of Bcl-2 action. EMBO J (2001) 20:2690–701. 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T, et al. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science (2003) 300:135–9. 10.1126/science.1081208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oakes SA, Scorrano L, Opferman JT, Bassik MC, Nishino M, Pozzan T, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK regulate the type 1 inositol trisphosphate receptor and calcium leak from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102:105–10. 10.1073/pnas.0408352102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinton P, Ferrari D, Magalhães P, Schulze-Osthoff K, Di Virgilio F, Pozzan T, et al. Reduced loading of intracellular Ca2+ stores and downregulation of capacitative Ca2+ influx in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells. J Cell Biol (2000) 148:857–62. 10.1083/jcb.148.5.857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bittremieux M, Parys JB, Pinton P, Bultynck G. ER functions of oncogenes and tumor suppressors: modulators of intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta (2016) 1863:1364–78. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bultynck G, Kiviluoto S, Henke N, Ivanova H, Schneider L, Rybalchenko V, et al. The C terminus of Bax inhibitor-1 forms a Ca2+-permeable channel pore. J Biol Chem (2012) 287:2544–57. 10.1074/jbc.M111.275354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiviluoto S, Schneider L, Luyten T, Vervliet T, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, et al. Bax inhibitor-1 is a novel IP3 receptor-interacting and -sensitizing protein. Cell Death Dis (2012) 3:e367. 10.1038/cddis.2012.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Høyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell (2007) 25:193–205. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balaban RS. The role of Ca2+ signaling in the coordination of mitochondrial ATP production with cardiac work. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1787:1334–41. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Territo PR, Mootha VK, French SA, Balaban RS. Ca2+ activation of heart mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation: role of the F(0)/F(1)-ATPase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (2000) 278:C423–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alers S, Löffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B. Role of AMPK-mTOR-Ulk1/2 in the regulation of autophagy: cross talk, shortcuts, and feedbacks. Mol Cell Biol (2012) 32:2–11. 10.1128/MCB.06159-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan K-L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol (2011) 13:132–41. 10.1038/ncb2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cárdenas C, Foskett JK. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signals in autophagy. Cell Calcium (2012) 52:44–51. 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Decuypere J-P, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca2+ in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium (2011) 50:242–50. 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams A, Hayashi T, Wolozny D, Yin B, Su T-C, Betenbaugh MJ, et al. The non-apoptotic action of Bcl-xL: regulating Ca2+ signaling and bioenergetics at the ER-mitochondrion interface. J Bioenerg Biomembr (2016) 48:211–25. 10.1007/s10863-016-9664-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White C, Li C, Yang J, Petrenko NB, Madesh M, Thompson CB, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum gateway to apoptosis by Bcl-XL modulation of the InsP3R. Nat Cell Biol (2005) 7:1021–8. 10.1038/ncb1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sano R, Hou Y-CC, Hedvat M, Correa RG, Shu C-W, Krajewska M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum protein BI-1 regulates Ca2+-mediated bioenergetics to promote autophagy. Genes Dev (2012) 26:1041–54. 10.1101/gad.184325.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cárdenas C, Müller M, McNeal A, Lovy A, Jaňa F, Bustos G, et al. Selective vulnerability of cancer cells by inhibition of Ca2+ transfer from endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Cell Rep (2016) 14:2313–24. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh A, Chagtoo M, Tiwari S, George N, Chakravarti B, Khan S, et al. Inhibition of inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor induce breast cancer cell death through deregulated autophagy and cellular bioenergetics. J Cell Biochem (2017). 10.1002/jcb.25891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wiel C, Lallet-Daher H, Gitenay D, Gras B, Le Calvé B, Augert A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium release through ITPR2 channels leads to mitochondrial calcium accumulation and senescence. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3792. 10.1038/ncomms4792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li C, Wang X, Vais H, Thompson CB, Foskett JK, White C. Apoptosis regulation by Bcl-x(L) modulation of mammalian inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel isoform gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2007) 104:12565–70. 10.1073/pnas.0702489104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Missiroli S, Bonora M, Patergnani S, Poletti F, Perrone M, Gafà R, et al. PML at mitochondria-associated membranes is critical for the repression of autophagy and cancer development. Cell Rep (2016) 16:2415–27. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giorgi C, Ito K, Lin H-K, Santangelo C, Wieckowski MR, Lebiedzinska M, et al. PML regulates apoptosis at endoplasmic reticulum by modulating calcium release. Science (2010) 330:1247–51. 10.1126/science.1189157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rong Y-P, Aromolaran AS, Bultynck G, Zhong F, Li X, McColl K, et al. Targeting Bcl-2-IP3 receptor interaction to reverse Bcl-2’s inhibition of apoptotic calcium signals. Mol Cell (2008) 31:255–65. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rong Y-P, Bultynck G, Aromolaran AS, Zhong F, Parys JB, De Smedt H, et al. The BH4 domain of Bcl-2 inhibits ER calcium release and apoptosis by binding the regulatory and coupling domain of the IP3 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:14397–402. 10.1073/pnas.0907555106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raturi A, Gutiérrez T, Ortiz-Sandoval C, Ruangkittisakul A, Herrera-Cruz MS, Rockley JP, et al. TMX1 determines cancer cell metabolism as a thiol-based modulator of ER-mitochondria Ca2+ flux. J Cell Biol (2016) 214:433–44. 10.1083/jcb.201512077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krols M, Bultynck G, Janssens S. ER-mitochondria contact sites: a new regulator of cellular calcium flux comes into play. J Cell Biol (2016) 214:367–70. 10.1083/jcb.201607124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giorgi C, Bonora M, Sorrentino G, Missiroli S, Poletti F, Suski JM, et al. p53 at the endoplasmic reticulum regulates apoptosis in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2015) 112:1779–84. 10.1073/pnas.1410723112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giorgi C, Bonora M, Missiroli S, Poletti F, Ramirez FG, Morciano G, et al. Intravital imaging reveals p53-dependent cancer cell death induced by phototherapy via calcium signaling. Oncotarget (2015) 6:1435–45. 10.18632/oncotarget.2935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Madreiter-Sokolowski CT, Gottschalk B, Parichatikanond W, Eroglu E, Klec C, Waldeck-Weiermair M, et al. Resveratrol specifically kills cancer cells by a devastating increase in the Ca2+ coupling between the greatly tethered endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cell Physiol Biochem (2016) 39:1404–20. 10.1159/000447844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang H, Shah K, Bradbury NA, Li C, White C. Mcl-1 promotes lung cancer cell migration by directly interacting with VDAC to increase mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and reactive oxygen species generation. Cell Death Dis (2014) 5:e1482. 10.1038/cddis.2014.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tosatto A, Sommaggio R, Kummerow C, Bentham RB, Blacker TS, Berecz T, et al. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulates breast cancer progression via HIF-1α. EMBO Mol Med (2016) 8:569–85. 10.15252/emmm.201606255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Doghman-Bouguerra M, Granatiero V, Sbiera S, Sbiera I, Lacas-Gervais S, Brau F, et al. FATE1 antagonizes calcium- and drug-induced apoptosis by uncoupling ER and mitochondria. EMBO Rep (2016) 17:1264–80. 10.15252/embr.201541504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Naon D, Scorrano L. At the right distance: ER-mitochondria juxtaposition in cell life and death. Biochim Biophys Acta (2014) 1843:2184–94. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giorgi C, Baldassari F, Bononi A, Bonora M, De Marchi E, Marchi S, et al. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and apoptosis. Cell Calcium (2012) 52:36–43. 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Calcium and cell death mechanisms: a perspective from the cell death community. Cell Calcium (2011) 50:211–21. 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Stefani D, Bononi A, Romagnoli A, Messina A, De Pinto V, Pinton P, et al. VDAC1 selectively transfers apoptotic Ca2+ signals to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ (2012) 19:267–73. 10.1038/cdd.2011.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zheng Y, Shen X. H2O2 directly activates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in endothelial cells. Redox Rep (2005) 10:29–36. 10.1179/135100005X21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marchi S, Rimessi A, Giorgi C, Baldini C, Ferroni L, Rizzuto R, et al. Akt kinase reducing endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release protects cells from Ca2+-dependent apoptotic stimuli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2008) 375:501–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Szado T, Vanderheyden V, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Rietdorf K, Kotelevets L, et al. Phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by protein kinase B/Akt inhibits Ca2+ release and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:2427–32. 10.1073/pnas.0711324105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rimessi A, Marchi S, Fotino C, Romagnoli A, Huebner K, Croce CM, et al. Intramitochondrial calcium regulation by the FHIT gene product sensitizes to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:12753–8. 10.1073/pnas.0906484106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene (2008) 27:6407–18. 10.1038/onc.2008.308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bonora M, Giorgi C, Pinton P. Novel frontiers in calcium signaling: a possible target for chemotherapy. Pharmacol Res (2015) 99:82–5. 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Florea A-M, Varghese E, McCallum JE, Mahgoub S, Helmy I, Varghese S, et al. Calcium-regulatory proteins as modulators of chemotherapy in human neuroblastoma. Oncotarget (2017) 8:22876–93. 10.18632/oncotarget.15283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hwang M-S, Schwall CT, Pazarentzos E, Datler C, Alder NN, Grimm S. Mitochondrial Ca2+ influx targets cardiolipin to disintegrate respiratory chain complex II for cell death induction. Cell Death Differ (2014) 21:1733–45. 10.1038/cdd.2014.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Galluzzi L. Novel insights into PML-dependent oncosuppression. Trends Cell Biol (2016) 26:889–90. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kasahara A, Scorrano L. Mitochondria: from cell death executioners to regulators of cell differentiation. Trends Cell Biol (2014) 24:761–70. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cogliati S, Enriquez JA, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial cristae: where beauty meets functionality. Trends Biochem Sci (2016) 41:261–73. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, et al. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105:15803–8. 10.1073/pnas.0808249105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morciano G, Giorgi C, Balestra D, Marchi S, Perrone D, Pinotti M, et al. Mcl-1 involvement in mitochondrial dynamics is associated with apoptotic cell death. Mol Biol Cell (2016) 27:20–34. 10.1091/mbc.E15-01-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morciano G, Pedriali G, Sbano L, Iannitti T, Giorgi C, Pinton P. Intersection of mitochondrial fission and fusion machinery with apoptotic pathways: role of Mcl-1. Biol Cell (2016) 108:279–93. 10.1111/boc.201600019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: an update and review. Biochim Biophys Acta (2006) 1757:509–17. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guo JY, Teng X, Laddha SV, Ma S, Van Nostrand SC, Yang Y, et al. Autophagy provides metabolic substrates to maintain energy charge and nucleotide pools in Ras-driven lung cancer cells. Genes Dev (2016) 30:1704–17. 10.1101/gad.283416.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lashinger LM, O’Flanagan CH, Dunlap SM, Rasmussen AJ, Sweeney S, Guo JY, et al. Starving cancer from the outside and inside: separate and combined effects of calorie restriction and autophagy inhibition on Ras-driven tumors. Cancer Metab (2016) 4:18. 10.1186/s40170-016-0158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.White E, Mehnert JM, Chan CS. Autophagy, metabolism, and cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21:5037–46. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bultynck G. Onco-IP3Rs feed cancerous cravings for mitochondrial Ca2+. Trends Biochem Sci (2016) 41:390–3. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mitra K, Wunder C, Roysam B, Lin G, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A hyperfused mitochondrial state achieved at G1-S regulates cyclin E buildup and entry into S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:11960–5. 10.1073/pnas.0904875106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hochegger H, Takeda S, Hunt T. Cyclin-dependent kinases and cell-cycle transitions: does one fit all? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2008) 9:910–6. 10.1038/nrm2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Finkel T, Hwang PM. The Krebs cycle meets the cell cycle: mitochondria and the G1-S transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:11825–6. 10.1073/pnas.0906430106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chang GG, Huang TM, Wang JK, Lee HJ, Chou WY, Meng CL. Kinetic mechanism of the cytosolic malic enzyme from human breast cancer cell line. Arch Biochem Biophys (1992) 296:468–73. 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90599-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Roderick HL, Cook SJ. Ca2+ signalling checkpoints in cancer: remodelling Ca2+ for cancer cell proliferation and survival. Nat Rev Cancer (2008) 8:361–75. 10.1038/nrc2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bernard D, Wiel C. Transport and senescence. Oncoscience (2015) 2:741–2. 10.18632/oncoscience.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ziegler DV, Wiley CD, Velarde MC. Mitochondrial effectors of cellular senescence: beyond the free radical theory of aging. Aging Cell (2015) 14:1–7. 10.1111/acel.12287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bittremieux M, Bultynck G. p53 and Ca2+ signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum: partners in anti-cancer therapies. Oncoscience (2015) 2:233–8. 10.18632/oncoscience.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.van Delft MF, Wei AH, Mason KD, Vandenberg CJ, Chen L, Czabotar PE, et al. The BH3 mimetic ABT-737 targets selective Bcl-2 proteins and efficiently induces apoptosis via Bak/Bax if Mcl-1 is neutralized. Cancer Cell (2006) 10:389–99. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature (2005) 435:677–81. 10.1038/nature03579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xie Q, Su J, Jiao B, Shen L, Ma L, Qu X, et al. ABT737 reverses cisplatin resistance by regulating ER-mitochondria Ca2+ signal transduction in human ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol (2016) 49:2507–19. 10.3892/ijo.2016.3733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dadi PK, Ahmad M, Ahmad Z. Inhibition of ATPase activity of Escherichia coli ATP synthase by polyphenols. Int J Biol Macromol (2009) 45:72–9. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Luyten T, Welkenhuyzen K, Roest G, Kania E, Wang L, Bittremieux M, et al. Resveratrol-induced autophagy is dependent on IP3Rs and on cytosolic Ca2+. Biochim Biophys Acta (2017). 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]