Abstract

The purpose of this study was to draw attention to the fact that the combined use of edaravone, diuretics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may lead to acute kidney injury. This study was a case report of acute kidney injury resulting from the combined use of the aforementioned types of drugs. A 77-year-old male patient with chronic kidney disease (third stage) who was treated with a combination of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs showed significantly increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Interestingly, the blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels returned to pretreatment levels after the medications were stopped. The patient’s score on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale was a nine, and the score on the Drug Interaction Probability Scale was a five. For elderly patients with chronic kidney disease, the combined use of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs should be avoided.

Keywords: Adverse drug reactions, Chronic kidney disease, Acute kidney injury

Introduction

Edaravone, mannitol, furosemide, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used in clinical medicine, but the combined use of these drugs can lead to acute kidney injury. Although this relationship has not been reported in China or any other country, the present study reports the occurrence of acute kidney injury in an elderly patient with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to the combined use of these drugs at the acute stage of cerebral infarction.

Case report

The patient was a 77-year-old male (body weight 58 kg, height 158 cm, and body mass index 23.23 kg/m2). Due to “sudden left limb weakness for 3 h,” he was sent to our hospital’s Neurology division at 14:30 on 5 February 2011. Three hours before the patient entered the hospital, he suddenly found his left upper limb to be very weak when he was cooking. His left hand failed to hold objects stably, and his pronunciation was unclear. He did not have a headache, nausea, disturbance of consciousness, body convulsions, or incontinence. A brain computed tomography (CT) scan was performed on the patient at a local hospital after the onset of the symptoms, and it did not reveal any bleeding lesions or emerging infarct. An intravenous infusion of “Shuxuening” (primarily consisting of flavonol glycosides and ginkgolides) plus mannitol (amount unknown) was administered, but the patient’s left lower limb began to appear to be very weak. In addition, he had difficulty walking and standing. He was then transferred to our hospital emergency room.

The patient had an 8-year history of hypertension, his highest systolic blood pressure was 180 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa), and he intermittently took captopril, metoprolol, and amlodipine. In the last 2 years, the patient stopped taking the drugs because he did not have any significant increase in his monitored blood pressure. He had a 5-year history of gout, and the lateral joints of two toes were in pain two to three times every year. When this pain occurred, colchicine relieved the symptoms. In July 2009, digital subtraction cerebral angiography indicated that his bilateral carotid arteries (both the subclavian arteries and the internal carotid arteries), bilateral anterior cerebral arteries, middle cerebral artery, bilateral vertebral arteries, and basilar artery were tortuous and rigid, and that the end of the left subclavian artery had narrowed by about 70 %. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in November 2010 revealed multiple lacunar infarcts, which affected the basal ganglia, the corona radiata region, and right occipital lobe malacia. In April 2010, the patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; however, his blood glucose was controlled with consistent administration of Humulin 70/30®. In December 2010, digital subtraction angiography suggested that the middle of the right coronary artery had narrowed by about 50 %, the opening near the end of the anterior descending artery had narrowed by 80 %, and the middle of the anterior descending artery had narrowed by 50 %. In addition, plaques were seen remotely. The patient had a 50-year history of smoking, and he reported smoking about 20 cigarettes daily. He also had a 40-year history of drinking, and 50–100 g of distilled liquor was consumed every day. The patient had not quit smoking or drinking before the onset of the stroke. There was no history of drug allergy.

Since July 2009, nocturia had taken place three to four times nightly. In the course of several hospitalizations, his renal function was tested and found to be abnormal (Table 1). According to the definition and staging standard [1] of CKD by the US Kidney Disease Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) expert group, the patient had been suffering from third stage CKD since July 2009.

Table 1.

Results of renal function tests since July 2009

| Time | Renal function | Cystatina (mg/l) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood urea nitrogena (mmol/l) | Serum creatininea (μmol/l) | Creatinine clearance rateb (ml/min) | ||

| 23/07/2009 | 5.50 | 123 | 37.63 | – |

| 22/08/2009 | 6.89 | 89.80 | 51.54 | 1.66 |

| 14/04/2010 | 11.24 | 124.70 | 36.55 | 1.62 |

| 11/12/2010 | 10.67 | 129.60 | 35.16 | 1.78 |

| 18/12/2010 | 10.06 | 111.40 | 40.91 | – |

| 29/12/2010 | 8.00 | 139.80 | 32.60 | 1.52 |

aAn Abbott automatic biochemical analyzer (Park, IL 60064) manufactured by the Toshiba Corp. in Japan (1385, Shimoishigami, Otawara-shi. Tochigi-ken, Japan was used). An Aerset Company device detected blood urea nitrogen using the urea enzyme method (reference range, 1.7–8.3 mmol/l), serum creatinine using the picric acid method (reference range, 44–120 μmol/l), and cystatin by immunoassay (reference range, 0–1.03 mg/l)

bCreatinine clearance rate (ml/min) = (140 − age) × body weight/(serum creatinine × 72) (age, in years; body weight in kg; serum creatinine in mg/dl, multiply by 88.4 μmol/l = 1 mg/dl) [2]. A total body weight of 58 kg was used for the determination of the creatinine clearance rate at all time points

In the hospital admission physical examination, the body temperature was 36.5 °C, the pulse was 72 beats/min, breathing was 20 times/min, and blood pressure was 147/86 mmHg. The patient was conscious, but he had unclear articulation and poor speech. In addition, the cardiac border was not enlarged, his heart rate was regular, no noise was heard from the valves, his lungs sounded clear with no dry or wet sound, his liver and spleen did not touch his ribs, and there was no vascular murmur. His eyes were staring to the right, and his pupils were equally round, large (3 mm in diameter), and sensitive to light reflected either directly or indirectly. Moreover, the left nasolabial fold was shallow, with limited tongue stretching. A score of 5 was given based on the improved classification score standard for swallowing function [3]. (The patient was told to swallow 5 ml of food paste at once; if he could swallow it without coughing, additional 5-ml increments of food paste were added to the original amount until 30 ml was swallowed at once. The patient’s swallowing function was evaluated according to his performance. One point indicated one swallow without coughing, two points indicated two swallows without coughing, three points indicated three swallows without coughing, four points indicated more than two swallows with coughing, and five points indicated that the patient was either unable to swallow with frequent coughing or was able to swallow any amount less than 30 ml in one swallow with coughing). Reduced muscle tension was found in the left lower and upper limbs, tendon reflexes were weaker, left upper limb muscle strength was grade 2 (within the possible range of grade 0–5), and lower limb muscle strength was grade 3. The right upper and lower limb extension force, tendon reflexes, and muscle strength were normal. Babinski’s sign was negative. Pain occurred in the left side of the body, and the patient had decreased sensitivity to temperature, decreased response to tuning fork vibration, and less sense of joint position. His neck was soft, his lower jaw was away from the sternum by the length of a finger, and the Brudzinski, Kernig, and Lasegue signs were all negative. The patient received a score of 10 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

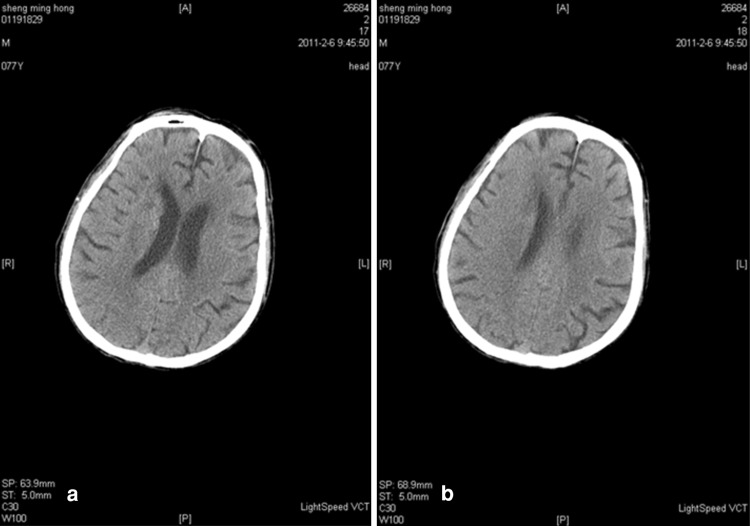

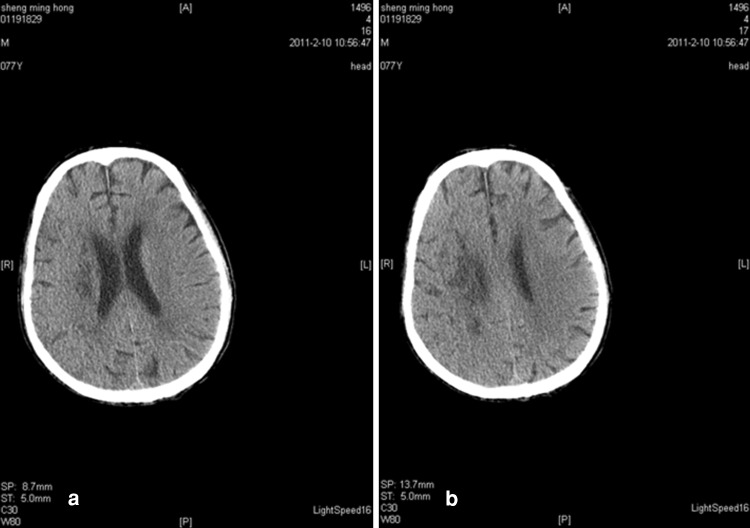

Upon hospital admission, urine flow cytometric analysis was normal, and renal function tests indicated third stage CKD (Table 2). During hospitalization, blood analysis showed that white blood cells were 8.20 g/l (the reference range was 4–10 g/l) and neutrophils were 91.90 % (the reference range was 50–70 %). Chest X-rays indicated infection in the lower sections of both lungs. A color Doppler ultrasound probe of the urinary system showed that the kidneys were normal with smooth encapsulated membranes. The left kidney section was 102 × 51 × 45 mm, and the right kidney was 94 × 49 × 44 mm. In addition, the renal-to-renal sinus proportion was normal; there was no separation between the renal pelvis and calyces, no expansion of the ureter, and no abnormal echo in the bladder area. Blood flow was significantly elevated in the initial renal artery segments, and the resistance index was high, which suggested that the initial renal artery segments were mildly stenotic (Table 3) [4]. Three days after the cerebral infarction, urine flow cytometry was normal. Blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.531 (the reference range was 7.35–7.45), a carbon dioxide partial pressure of 28.10 mmHg (the reference range was 35.25–45 mmHg), and an oxygen partial pressure of 80.40 mmHg (the reference range was 94.50–99.76 mmHg). In addition, the actual bicarbonate, standard bicarbonate, whole blood buffer base, base excess, and oxygen saturation were all within their normal ranges. As of 16 February 2011, ten blood electrolyte tests showed that potassium, sodium, chloride, and calcium were within their normal ranges. At 22 h after the onset of the sickness, a brain CT scan indicated low-density spots in the right parietal occipital area and corona radiata region. In addition, the sulcus and grooves were wider and deeper, but there was not a shift in the midline structures. Thus, we concluded that the right parietal occipital area and corona radiata had suffered from brain infarction and brain atrophy (Fig. 1). Five days after the onset of the sickness, another brain CT scan indicated low-density spots and flakes in the right parietal occipital area and corona radiata. Compared with the previous scan, there were new lesions, and the sulcus and grooves were wider and deeper, but there was still no shift of the midline structures, which led us to the same conclusion as the previous findings (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Daily fluid intake, urine output, and renal function test results before and after the occurrence of acute kidney injury

| Time | Intake and urine output (ml) | Renal function | Cystatin (mg/l) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intake | Urine output | Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/l) | Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | Creatinine clearance rate (ml/min) | ||

| 02/05 14:30–02/06 07:00 | – | – | 10.95 | 110.80 | 40.49 | 1.19 |

| 02/06 07:00–02/07 07:00 | 2,750 | 2,180 | 12.11 | 157.40 | 28.50 | – |

| 02/07 07:00–02/08 07:00 | 4,755 | 520 | 21.26a | 407.40a | 11.01 | 2.48a |

| 02/08 07:00–02/09 07:00 | 2,929 | 2,080 | 20.40 | 431.60 | 10.39 | 2.55 |

| 02/09 07:00–02/10 07:00 | 4,002 | 2,840 | 23.51 | 362.20 | 12.39 | 2.37 |

| 02/10 07:00–02/11 07:00 | 4,073 | 2,400 | 19.60 | 194.70 | 23.04 | – |

| 02/11 07:00–02/12 07:00 | 4,447 | 3,550 | 16.10 | 129.50 | 34.64 | – |

| 02/12 07:00–02/13 07:00 | 4,635 | 3,540 | 12.12 | 104.30 | 43.01 | – |

aBlood test results after the last application of edaravone, mannitol, and compound aminopyrine

Table 3.

The detection results of renal artery color Doppler ultrasound

| Renal artery | Left renal artery | Right renal artery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak velocity (cm/s) | Resistance index | Peak velocity (cm/s) | Resistance index | |

| Initial segment | 222 | 0.83 | 243 | 0.82 |

| Renal hilar | 81 | 0.87 | 66 | 0.80 |

An iU22 Color Doppler manufactured by the Philips Co., The Netherlands, was used for detection. The diagnostic criterium of the resistance index (RI) value for prerenal acute renal failure was >0.75 [4], and the abdominal aortic peak flow rate of the patient at the beginning of the renal artery was 80 cm/s; the reference renal artery peak velocity was ≤2.5 × 80 cm/s

Fig. 1.

a, b CT scan of the brain 22 h after the onset of the stroke [scanned by a Lightspeed volume computed tomography (VCT) scanner, manufactured by GE Healthcare, USA]. Low-density spots were seen in the right parietal occipital lobe and corona radiata

Fig. 2.

a, b CT scan of the brain 5 days after the onset of the stroke. Low-density spots were seen in the right parietal occipital lobe and corona radiata. The right parietal occipital area and corona radiata showed flaky low-density spots. A comparison of the two CT scans shows that new lesions were detected at 5 days

Based on the patient’s pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, past medical history, neurological signs, and brain CT scan results, the diagnosis was cerebral infarction, pseudobulbar palsy, third degree hypertension (thus placing the patient in a high-risk group), type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, second degree heart function, and third stage CKD. Xuesaitong (main ingredient Panax notoginseng saponins), Ozagrel, edaravone, and Humulin 70/30® were given to inhibit platelet aggregation, improve cerebral blood circulation, scavenge free radicals, and reduce blood sugar. One hour after admission to the hospital, the patient’s level of consciousness and left lower limb muscle strength gradually decreased, and his NIHSS score was 19. Because infarct expansion and increased intracranial pressure were suspected, an intravenous injection of mannitol (20 %), compound glycerol, and furosemide was given. Fifteen hours after admission to the hospital, the patient had increased respiratory secretions, his body temperature had increased to 39.4 °C, and his lungs contained sputum. Based on the results of blood analysis and chest X-rays, the patient was diagnosed with a pulmonary infection. The patient was administered intravenous injections of levofloxacin and cefoperazone/sulbactam, and an intramuscular injection of compound aminopyrine (0.143 g aminopyrine and 0.057 g sodium pentobarbital in 2 mL). In addition, a diclofenac suppository was inserted into the rectum. The patient also received a warm sponge bath, and cold pads were applied on the arteries of his neck and limbs. During the cooling process, the patient sweated more, his level of consciousness continued to diminish, and his blood pressure decreased (the minimum value was 128/80 mmHg. At 28 h, 22 h, 5 h, and 1 h after the first administration of edaravone, mannitol, compound aminopyrine, and diclofenac, respectively, the patient’s blood urea nitrogen and creatinine increased, and his creatinine clearance rate decreased (Table 2). At 41.5, 35.5, 18.5, and 14.5 h after the first administration of edaravone, mannitol, compound aminopyrine, and diclofenac, respectively, the patient urinated less. When the acute kidney injury was at its worst, urine production over a 24-h period was 520 ml, blood urea nitrogen was 23.51 mmol/l, creatinine was 431.60 μmol/l, and the creatinine clearance rate was 10.39 ml/min (Table 2). Based on the patient’s medical history, clinical symptoms, renal function test results, and relevant diagnostic criteria [1, 5], the patient was diagnosed with third stage CKD and acute kidney injury. After this analysis, the administration of the drugs, including edaravone, mannitol, and NSAIDs, was terminated. The cumulative amounts of edaravone, mannitol, compound aminopyrine, and diclofenac sodium that the patient had received were 180 mg, 975 ml (excluding the amount taken outside the hospital), 10 ml, and 25 mg, respectively. After terminating the use of the above drugs, compound amino acid 9R injection fluid was used to supplement blood circulation and treat the symptoms. The patient’s renal function rapidly recovered to the level measured before the drug intake (Table 2).

The present patient was followed for 5 months. The patient's daily urine volume was about 1,400 ml, and the frequency of nocturia was three to four times per night. On 25 February 2011, the blood urea nitrogen was 7.86 mmol/l, creatinine was 100.60 μmol/l, cystatin was 1.16 mg/l, and creatinine clearance rate was 41.52 ml/min (body weight, 54 kg). On 16 July 2011, the blood urea nitrogen level was 5.48 mmol/l, creatinine was 77.20 μmol/l, the creatinine clearance rate was 43.09 ml/min (body weight, 45 kg), and the NIHSS score was nine.

Discussion

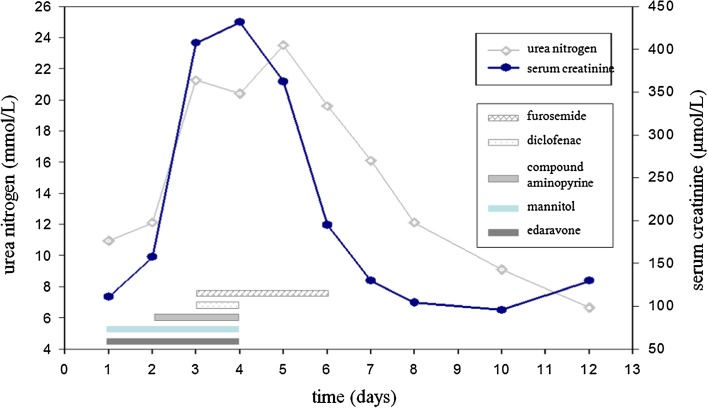

This study examined a patient with a history of CKD (third stage) in whom acute kidney injury occurred during treatment for a cerebral infarction. Analysis revealed that the acute kidney injury happened after the patient had taken edaravone, mannitol, and NSAIDs. In addition, when the drugs were terminated, the patient’s renal function rapidly recovered to the pretreatment level (Fig. 3). Clinical reports and animal experiments have shown that the use of edaravone, mannitol, or NSAIDs alone can cause acute renal failure [6–12]. Examination revealed that the patient received a score of nine on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale [13], which indicated that the application of these drugs had a “definite” causal relationship with the acute kidney injury. The patient also had a score of five on the Drug Interaction Probability Scale [14], which indicated that these drugs had a “probable” interaction. Therefore, there is a strong indication that the acute kidney injury was due to an adverse reaction to the drugs.

Fig. 3.

Use of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs, and their relation over time to blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels

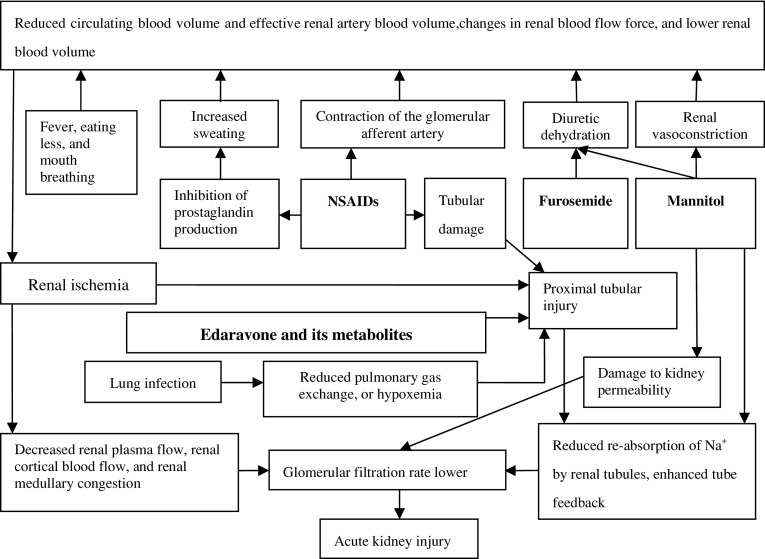

Although edaravone and its metabolites are speculated to have toxic effects on the kidneys [7], the pathogenesis of edaravone-induced acute renal injury is currently unclear [7, 8]. The mechanisms by which mannitol causes acute renal injury include dehydration, enhanced tubuloglomerular feedback, permeability damage, and renal vasoconstriction [15]. The normal half-life of mannitol is 1.2 h, but this is significantly extended in older CKD patients [11]. Although the cumulative amount of mannitol in this patient was not large, the mannitol excretion rate was low because of the presence of CKD, and renal toxicity accumulated. Aminopyrine and diclofenac are both NSAIDs. Through the suppression of cyclooxygenase, NSAIDs selectively inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which results in peripheral vasodilation and sweating. After administration of NSAIDs in elderly patients, increased sweating and decreased circulating blood volume frequently cause the level of consciousness to decline, which can lead to kidney damage. Through the contraction of afferent arterioles, NSAIDs reduce renal blood flow and increase renal injury. During the course of repeated administration of NSAIDs, our patient sweated more, his level of consciousness declined further, and his renal function worsened. In addition, diclofenac sodium can damage the proximal and distal tubules [16]. As shown in Fig. 4, furosemide administration magnified the dehydration effect of mannitol, which led to a further reduction in circulating blood volume in the patient and increased the renal injury. Note that for 3 days after the incident, furosemide was administered repeatedly. Interestingly, the patient’s renal function recovered rapidly after the termination of edaravone, mannitol, and NSAIDs (Fig. 3). Thus, when furosemide was not used with edaravone, mannitol, and/or NSAIDs, its renal toxicity was not apparent. Huerta et al. [17] reported that the use of furosemide with NSAIDs significantly increased the risk of renal injury.

Fig. 4.

The assumed mechanisms by which co-administration of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs cause acute kidney injury

In addition to the adverse reactions to edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs, acute phase complications may have been involved in the pathological process of renal injury on multiple levels. For example, lung infection can induce fever, and infection can aggravate the extent of renal injury by edaravone [10]. In addition, fever can increase nonobvious water loss. Moreover, having dysphagia before the establishment of a nasogastric tube, the patient had not had anything to eat or drink for 22 h. Furthermore, mouth breathing was utilized after the patient was admitted to the hospital, and this can also increase water loss. Taken together, these factors may have further decreased blood circulation, promoted the occurrence of renal injury, and/or increased the severity of renal injury.

Clinical studies have reported that long-term hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, renal arteriosclerosis, ischemic heart disease, and smoking can cause CKD [18–23]. In the present patient, multiple chronic diseases and a long-term smoking habit led to the occurrence of CKD. In addition to CKD, the patient also had acute kidney injury. The present case study demonstrated that the combined use of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs should be avoided in elderly patients with CKD and other potential chronic diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have shown that the combined use of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs leads to acute kidney injury in elderly CKD patients. Although we cannot accurately define the degree of impact that each of these drugs had on the renal injury, we at least proved the existence of renal injury due to the combined use of these drugs.

The Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale is a practical tool for clinical evaluation. It evaluates clinically the correlation between drugs and clinical adverse events or, we could say, whether these adverse events are the result of the adverse reaction to this drug. It was shown that the adverse drug reaction probability scale has consensual, content, and concurrent validity. This systematic method offers a sensitive way to monitor adverse drug reactions [13]. Examination revealed that the patient received a score of nine on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale [13], which indicated that the application of these drugs had a "definite" causal relationship with the acute kidney injury. However, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale is another tool that clinically evaluates whether there is interaction between drugs. The patient had a score of five on the Drug Interaction Probability Scale [14], which indicated that these drugs had a “probable” interaction. The Drug Interaction Probability Scale can serve as a guide in the preparation of articles describing case reports of drug interactions as well as in the evaluation of published case reports [14]. At present, these two scales have been widely used in case reports involving clinical adverse drug reactions [24–28] and post-marketing assessments of adverse drug reactions and related effects [29].

It should be noted that ten blood electrolyte tests within 10 days after the accident all showed normal results. Three days after the accident, urine flow cytometry indicated positive urine protein. Four days after the accident, the level of serum β2-microglobulin significantly increased (6,718.60 μg/l; reference range, 1,473–2,454 μg/l). Moreover, 3 consecutive days after the accident, the level of serum cystatin significantly increased (Table 2), but it fell back to the level before the accident in the 3rd week after this accident. Due to the limitations of technology and conditions at our hospital, we did not measure the levels of urine, and serum urinary alanine aminopeptidase and N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase (NAG). We were also unable to measure the level of urine β2-microglobulin and cystatin. Since the accident occurred during the 2011 Chinese New Year, we did not measure the urine protein and urine sodium levels because of personnel and equipment deployment problems. By observing the clearance rate of blood urine nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine and creatinine as well as changes in the level of serum cystatin after the accident, we believed that early discovery, immediate drug discontinuance, and symptomatic treatment would have been able to reverse the acute renal injury caused by the combined use of edaravone, diuretics, and NSAIDs.

What we must remember after analyzing the cause of acute renal injury in this case is that factors including age, BMI, and conversion of the creatinine clearance rate should also be taken into consideration to further assess renal function apart from the levels of serum beta 2-microglobulin and cystatin if the patient’s blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels are normal. If permitted, serum levels of urinary alanine aminopeptidase and NAG, as well as the levels of beta 2-microglobulin and cystatin in urine, should also be examined. If the patient suffers from renal hypofunction or has a CKD history, no edaravone should be administered, not to mention combined therapy with dehydrating diuretics and NSAIDs, particularly in the case of an elderly patient.

Interestingly, a brain CT scan on the 5th day after symptom onset revealed an emerging infarct in the right subcortical region, which appeared as spots and flakes (i.e., the cerebral infarction area in the patient was not large at that time). Here, we retrospectively analyzed the decreased consciousness level of the patient when fever was present and before the use of diuretics and NSAIDs (this decrease may have been related to reduced cerebral perfusion at the early stage of cerebral infarction). A decreased level of consciousness in the course of cerebral infarction should be analyzed and handled carefully because it cannot be treated in the same manner as cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the American Journal Experts for their help in translation.

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest among the authors.

Ethics statement

The patient’s family and Taihe Hospital Affiliated with Hubei University of Medicine Hospital Medical Ethics Committee provided consent for this written report.

Footnotes

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Guang Jian Liu, FAX: +8607198883809, Email: yymclgj65@yahoo.com.cn.

Yun Fu Wang, Email: thyywyf@hotmail.com.

Yan Jun Zeng, FAX: +861067351975, Email: yjzeng@bjut.edu.cn.

Li Ding, Email: liding85@hotmail.com.

Guo Jun Luo, Email: junlgsy@yahoo.com.cn.

Li Ping Zhang, Email: thyyzlp@hotmail.com.

Jian’e Zhang, Email: janezhang55@163.com.

References

- 1.Bolton K, Culleton B, Harvey KS, Ikizler TA, Johnson CA, Kausz A, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. [2012-4-20]. http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm.

- 2.Bolton K, Coresh J, Culleton B, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. [2011-6-20] http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm.

- 3.Liu GJ, Wang YF, He GH, Luo GJ, Wang JH, Li HC, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen, swallowing training and acupuncture on Fengchi site to treat dysphagia due to pseudo-bulbar palsy after stroke. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;32:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nori G, Granata A, Leonardi G, Sicurezza E, Spata C. The US color Doppler in acute renal failure. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2004;56:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez GS, Garcia RLA, Raiford DS, Duque OA, Ris RJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of hospitalization for acute renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2433–2439. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.21.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe M, Kaizu K. Matsumoto K.A case report of acute renal failure and fulminant hepatitis associated with edaravone administration in a cerebral infarction patient. Ther Apher Dial. 2007;11:235–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hishida A. Clinical analysis of 207 patients who developed renal disorders during or after treatment with edaravone reported during post-marketing surveillance. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11:292–296. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besen A, Kose F, Paydas S, Gonlusen G, Inal T, Dogan A, et al. The effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac sodium on the rat kidney, and alteration by furosemide. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:919–926. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hishida A. Determinants for the prognosis of acute renal disorders that developed during or after treatment with edaravone. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai SF, Shu KH. Mannitol-induced acute renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(1):70–73. doi: 10.5414/cnp74070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang L, You H, Chen B, Xu Z, Gao L, Liu J, et al. Mannitol is an independent risk factor of acute kidney injury after cerebral trauma: a case-control study. Ren Fail. 2010;32:673–679. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.486492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(4):674–680. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadallah MF, Lynn M, Work J. Case report: mannitol nephrotoxicity syndrome: role of hemodialysis and postulate of mechanisms. Am J Med Sci. 1995;309(4):219–222. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yasmeen T, Qureshi GS, Perveen S. Adverse effects of diclofenac sodium on renal parenchyma of adult albino rats. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huerta C, Castellsague J, Varas-Lorenzo C, Garcia RLA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of ARF in the general population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:531–539. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afghahi H, Cederholm J, Eliasson B, Zethelius B, Gudbjornsdottir S, Hadimeri H, et al. Risk factors for the development of albuminuria and renal impairment in type 2 diabetes—the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010. (PubMed:20817668). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gombos P, Langer RM, Korbely R, Varga M, Kaposi A, Dinya E, et al. Smoking following renal transplantation in Hungary and its possible deleterious effect on renal graft function. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2357–2359. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu C, Zhao H, Xu G, Yue H, Liu W, Zhu K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease in a Uygur adult population from Urumqi. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2010;30:604–610. doi: 10.1007/s11596-010-0550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Saeed HNS, Hajghasemi E, Nozari B, Zinat NH, Mahdavi A. Screening for decreased renal function in taxi drivers in Tehran. Iran Ren Fail. 2010;32:62–68. doi: 10.3109/08860220903491190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauriasari R, Sakano N, Wang DH, Takaki J, Takemoto K, Wang B, et al. C-reactive protein is associated with cigarette smoking-induced hyperfiltration and proteinuria in an apparently healthy population. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su BY, Lai HM, Chen CJ, Chen YC, Chiu CK, Lin KM, et al. Ischemia heart disease and greater waist circumference are risk factors of renal function deterioration in male gout patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:581–586. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0750-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oteri A, Bussolini A, Sacchi M, Clementi E, Zuccotti GV, Radice S. A case of atrial fibrillation induced by inhaled fluticasone propionate. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1237–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figueira-Coelho J, Pereira O, Picado B, Mendonca P, Neves-Costa J, Neta J. Acute hepatitis associated with the use of levofloxacin. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1733–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomo C, Coriat R, Faivre L, Mir O, Ropert S, Billemont B, et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction involving sorafenib and the calcium-channel blocker felodipine in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:1511–1514. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roustit M, Blondel E, Villier C, Fonrose X, Mallaret MP. Symptomatic hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and repaglinide in a diabetic patient. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:764–767. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnoldi J, Repking N. Olanzapine-induced parkinsonism associated with smoking cessation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:399–401. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwamoto T, Ishibashi M, Fujieda A, Masuya M, Katayama N, Okuda M. Drug interaction between itraconazole and bortezomib: exacerbation of peripheral neuropathy and thrombocytopenia induced by bortezomib. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:661–665. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.7.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]