Abstract

Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne disease with diverse clinical presentations, ranging in severity from a flu-like illness with fever and myalgias to a serious systemic disease with multisystem organ failure. Nephrotic syndrome has been reported previously in two cases of human ehrlichiosis. A kidney biopsy revealed minimal change disease in one of those patients. Herein, we present the case of a 40-year-old man with ehrlichiosis who developed nephrotic syndrome, cryoglobulinemia, and secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN). The patient originally presented with shortness of breath, diffuse myalgias, headache, and lower extremity edema. He subsequently developed acute kidney injury and underwent kidney biopsy which showed MPGN and acute tubular injury. A tick-borne disease panel was positive for IgM and IgG to Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Serum testing revealed type 3 mixed cryoglobulinemia with no evidence of hepatitis C infection. The cryoprecipitate contained IgM and IgG antibodies to E. chaffeensis. Cryoglobulinemia is frequently associated with infections, particularly hepatitis C; however, our case is the first to describe ehrlichiosis associated with cryoglobulinemia and secondary MPGN.

Keywords: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, Nephrotic syndrome, Ehrlichiosis, Infection, Cryoglobulinemia

Introduction

Human ehrlichiosis is caused by a group of tick-transmitted bacteria in the genus Ehrlichia. The bacteria are obligate intracellular gram-negative bacilli in the order Rickettsiales. Ehrlichiosis has long been recognized as a disease in animals, and more recently as a significant human disease [1–3]. One Ehrlichia species, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, is responsible for the majority of human infections [1, 2]. Symptoms range in severity from a flu-like illness with fever, headache, and myalgias to a severe systemic illness with liver failure, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and septic shock [2].

Dogs experimentally infected with Ehrlichia canis developed malaise, fever, thrombocytopenia, and proteinuria following inoculation [4, 5]. Renal pathology in one dog showed granular IgM antibody deposits in the mesangium and capillary loops, podocyte foot process effacement, and mesangial proliferation [5]. Development of severe nephrotic syndrome has also been reported in two cases of human ehrlichiosis [6, 7]. One of those patients underwent a kidney biopsy that showed changes consistent with minimal change disease with foot process effacement, but no mesangial cell proliferation, glomerular basement membrane thickening, or significant immunoglobulin deposition [7]. The present report describes a patient with ehrlichiosis associated with nephrotic syndrome, cryoglobulinemia, and secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN).

Case report

A 40-year-old white male with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department in late June complaining of shortness of breath, diffuse myalgias, headache, and lower extremity edema. His temperature was 36.9 °C, blood pressure was 163/100 mmHg, heart rate was 95 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 24/min with an oxygen saturation of 97 % on room air. His physical exam showed bibasilar rales, a 2/6 systolic ejection murmur, and 1 + lower extremity edema. Initial laboratory evaluation showed pancytopenia with a white blood cell count of 3,000/mm3 (normal value 4,100–10,800/mm3), hemoglobin of 10.2 g/dl (normal value 13.7–17.5 g/dl), and a platelet count of 100,000/mm3 (normal value 140,000–370,000/mm3). Blood chemistries showed a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 18 mg/dl (6.43 mmol/l) (normal value 7–20 mg/dl) and creatinine of 0.9 mg/dl (79.6 μmol/l) (normal value 0.7–1.4 mg/dl). Albumin was 2.9 g/dl (normal value 3.5–5 g/dl). The urinalysis showed a specific gravity of 1.027, protein concentration >600 mg/dl, 15–29 red blood cells, and 5–9 white blood cells. A 24-h urine collection contained 18.97 g of protein and demonstrated a creatinine clearance of 174 ml/min (2.9 ml/s). The total volume was 1,300 ml and the total excreted creatinine was calculated at 15.72 mg/kg body weight. The complement C3 and C4 levels were within normal limits. The serum protein electrophoresis showed increased alpha-1 globulin and hypoalbuminemia. The HIV screen and hepatitis panel were negative.

Diuresis with intravenous furosemide resulted in resolution of dyspnea. BUN and creatinine were unchanged throughout the hospitalization. A bone marrow biopsy for evaluation of pancytopenia was non-diagnostic. On the 5th hospital day, the patient developed erythema and edema of his left hand. Evaluation by hand surgery diagnosed inflammation due to infiltration of an intravenous line, and the patient was discharged home with lisinopril 20 mg daily, warm compresses, and outpatient follow-up.

Three days after discharge the patient was re-admitted with increased left-hand edema, erythema, and fever of 39.4 °C. Physical exam demonstrated a fluctuant, erythematous 4 cm by 3 cm lesion on the dorsum of his left hand. Laboratory evaluation showed acute kidney injury with a BUN of 35 mg/dl (12.5 mmol/l) and creatinine of 2.8 mg/dl (247.5 μmol/l). The patient had persistent pancytopenia with a WBC count of 3,200/mm3, hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dl, and a platelet count of 71,000/mm3. The albumin was 2.5 g/dl. Urinalysis showed specific gravity of 1.020, >50 RBC, 15–29 WBC, and 100 mg/dl protein. Fractional excretion of sodium was less than 1 %. Complement C3 and C4 levels were 56.2 mg/dl (normal value 80–150 mg/dl) and 17.8 mg/dl (normal value 14–40 mg/dl), respectively. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody levels were negative.

Lisinopril was stopped and the patient was placed on ampicillin/sulbactam and vancomycin for soft tissue infection. He underwent incision and drainage of the left-hand abscess. His blood and wound cultures grew methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. As repeat blood cultures grew S. aureus, a transesophogeal echocardiogram was performed that revealed a congenitally bicuspid aortic valve with mild aortic stenosis and mild aortic insufficiency. Although no distinct vegetations were seen, 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated because of diffuse thickening of the valve leaflets.

The patient had an episode of hypotension on hospital day 1 and received volume resuscitation with normal saline. Despite resolution of his hypotension, he became oliguric and his creatinine continued to rise. His renal ultrasound demonstrated normal renal echogenicity without hydronephrosis. The patient was initiated on renal replacement therapy on hospital day 4.

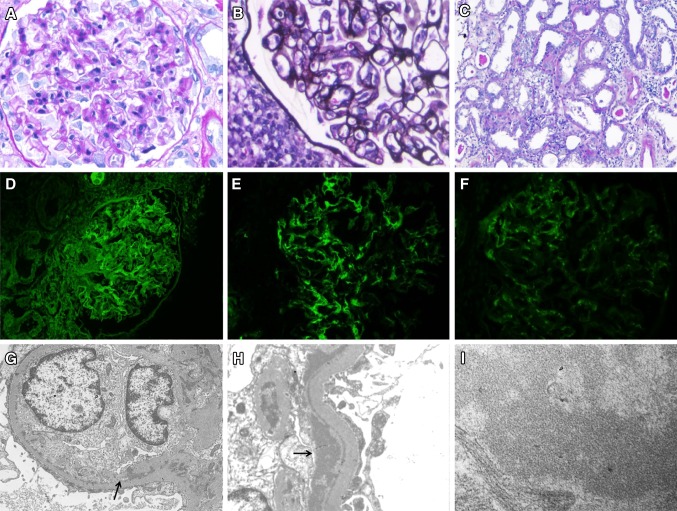

The patient underwent a kidney biopsy on hospital day 8 that showed both secondary MPGN and acute tubular injury (ATI). The ATI involved approximately 50 % of the tubules and was characterized by tubular dilatation with sloughing of the tubular epithelial cells and loss of tubular brush borders (Fig. 1c). The biopsy contained eight glomeruli that showed mesangial proliferation and glomerular basement membrane splitting (Fig. 1a, b). Immunofluorescence microscopy was positive for IgG, IgM, and C3 (Fig. 1d, e, f) with dominant IgM staining in a diffuse granular and chunky capillary pattern (Fig. 1e). Electron microscopy showed mesangial interposition into the capillary wall and subendothelial electron dense deposits with a substructure suggestive of microtubules (Fig. 1g, h, i). There was no segmental or global sclerosis, endocapillary proliferation, crescents, or fibrinoid necrosis. There was no evidence of diabetic nephropathy.

Fig. 1.

Kidney histology demonstrating secondary MPGN and ATI. a Periodic acid–Schiff-stained section showing an enlarged glomerulus with mesangial proliferation (original magnification ×40). b Micrograph of Jones’ silver stain showing an enlarged glomerulus with mesangial proliferation and splitting of basement membranes (original magnification ×40). c Periodic acid–Schiff-stained section in which diffuse ATI is indicated by flattening of epithelial cell lining, loss of brush border, and sloughing of epithelial cell lining (original magnification ×20). d Immunofluorescence micrograph showing diffuse granular staining for IgG along glomerular capillaries. e Immunofluorescence micrograph showing diffuse granular and chunky capillary staining for IgM. f Immunofluorescence micrograph showing granular capillary staining for C3. g Electron microscopy image showing capillary mesangial interposition (arrow) and mesangial and subendothelial deposits (original magnification ×7,100). h Electron microscopy image showing subendothelial electron dense deposits (arrow) and epithelial cell foot process effacement (original magnification ×14,000). i Electron microscopy image of a subendothelial deposit showing features suggestive of a microtubular substructure (original magnification ×56,000)

Based on the interpretation of the electron microscopy, serum cryoglobulins were obtained and were positive. Immunofixation electrophoresis detected mixed polyclonal paraproteins consistent with type III mixed cryoglobulinemia. Repeat hepatitis panel was negative, and hepatitis C polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative for hepatitis C RNA in the serum. A tick-borne disease panel was positive for IgM and IgG antibodies reactive against E. chaffeensis with titers of 1:20 and 1:64, respectively. Further testing revealed that his cryoprecipitate contained both IgM and IgG antibodies against E. chaffeensis. Evaluation of paraffin embedded tissue from the kidney biopsy by the Centers for Disease Control showed no immunohistochemical evidence of Ehrlichia species in the tissue. A bone marrow biopsy showed trilineage hyperplasia and increased megakaryocytes. Flow cytometry and cytogenetic testing were within normal limits, and there was no evidence of dysplasia. Table 1 provides a summary of key diagnostic labs for this case.

Table 1.

Summary of key diagnostic tests

| Diagnostic test | Result |

|---|---|

| Serum protein electrophoresis | Increased alpha-1 globulin and hypoalbuminemia Negative for paraprotein |

| Urine protein electrophoresis | 18.97 g protein in 24-h collection Negative for paraprotein |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Negative |

| Hepatitis B antibody | Negative |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative |

| Hepatitis C PCR | No RNA detected |

| Bone marrow aspirate | Negative for dysplasia |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis IgM/IgG | Positive 1:20/positive 1:64 |

| Serum cryoglobulins | Positive for type 3 mixed cryoglobulins |

| Cryoprecipitate | Positive for IgM and IgG to Ehrlichia chaffeensis |

| Immunohistochemistry of kidney tissue for Ehrlichia species | Negative |

Laboratory tests critical to the patient’s diagnosis of ehrlichiosis and mixed cryoglobulinemia with secondary MPGN are listed. Note that other potential etiologies of cryoglobulinemia with secondary MPGN are negative including hepatitis and hematologic malignancies

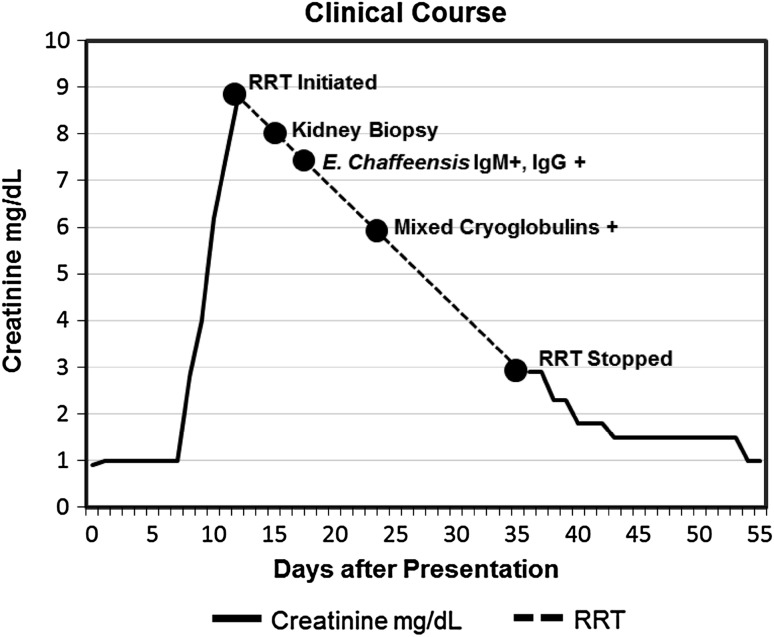

The patient was treated with 14 days of doxycycline for ehrlichiosis. After finding cryoglobulins in the serum, he was placed on prednisone and received plasmapheresis for 3 treatments. He continued on intermittent renal replacement therapy throughout his hospitalization and for 1 week following discharge. His creatinine returned to baseline 18 days after his last hemodialysis treatment. The patient was last seen in clinic 105 days after initial presentation and was then lost to follow-up. At this appointment, the patient’s creatinine was 1.1 mg/dl (97.2 μmol/l) and his proteinuria was subnephrotic with a protein to creatinine ratio of 2.04 g/g. His pancytopenia had also completely resolved. Table 2 illustrates renal function and hematology lab results from presentation to last follow-up visit. His clinical course is represented graphically in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Renal function and hematology lab results from presentation (day 0) to last follow-up visit (day 105)

| BUN (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | Albumin (g/dl) | UPCR (g/g) | WBC × 103/μl | Hgb (g/dl) | Platelets × 103/μl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 18 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 18.97* | 3 | 10.2 | 100 |

| Day 8 | 35 | 2.8 | 2.5 | NC | 3.2 | 9.2 | 71 |

| Day 12 | 66 | 8.8 | 2.6 | NC | 3.1 | 8.1 | 110 |

| Day 36 | 77 | 2.9 | NC | NC | 5 | 8.2 | 179 |

| Day 38 | 61 | 2.3 | NC | NC | 5 | 8.8 | 193 |

| Day 54 | 42 | 1 | 3 | NC | 7.5 | 10.7 | 107 |

| Day 87 | 37 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 2.66 | 10.2 | 12.5 | 262 |

| Day 105 | 20 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 2.04 | 8.1 | 12.1 | 295 |

BUN blood urea nitrogen, UPCR urine protein/creatinine ratio, Hgb hemoglobin, NC not collected

* Value from 24-h urine collection that was initiated on presentation and not from random protein/creatinine ratio

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of clinical course. Creatinine over time (solid line) is shown graphically from presentation (day 0) until recovery to baseline (day 54). Creatinine measurements are not shown while patient was on renal replacement therapy (RRT) (broken line). Key events during hospital course are noted on the timeline including RRT initiation, kidney biopsy, ehrlichiosis diagnosis, cryoglobulinemia diagnosis, and cessation of RRT. Patient underwent RRT with intermittent hemodialysis beginning 12 days after initial presentation. His last dialysis treatment was 36 days after initial presentation

Discussion

Our patient presented in an endemic area during peak ehrlichiosis season [2]. His initial presentation with headache, myalgias, and pancytopenia is consistent ehrlichiosis. His second presentation was complicated by S. aureus bacteremia and acute kidney injury. Kidney biopsy demonstrated two distinct types of renal injury, MPGN, and ATI, with the latter primarily contributing to acute kidney injury. At the time of biopsy, the patient had several risk factors for ATI including underlying nephrotic syndrome, hypotension, and sepsis [8, 9]. The biopsy finding of MPGN explained the patient’s nephrotic syndrome which preceded his episode of AKI. MPGN describes a pattern of glomerular injury seen in multiple settings including infections, autoimmune diseases, hematologic malignancies, and alterations in complement [10]. It is the pattern of glomerular injury most commonly seen with mixed cryoglobulinemia [11].

Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C [12]. They are generated by clonal expansion of B cells which occurs in lymphoproliferative disorders or in the presence of chronic immune stimulation from autoimmune diseases or infections [12]. Cryoglobulins are classified according to type and clonality of immunoglobulin. Type I consists of monoclonal immunoglobulin which can be IgM or IgG. Type II and III are referred to as mixed cryoglobulins because they contain both IgM and IgG. Type II contains monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG, while type III contains polyclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG [12].

Type I cryoglobulinemia is primarily associated with lymphoproliferative disorders, while mixed cryoglobulinemia is most frequently associated with chronic hepatitis C infection, accounting for at least 70 % of cases [11]. Additional etiologies of mixed cryoglobulinemia include other chronic infections, autoimmune disorders, and hematologic malignancies [11–13]. Our patient had no evidence of autoimmune disorder, hematologic malignancy, or hepatitis C infection. Other infections that have been associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia include hepatitis B, Epstein–Barr virus, HIV, Streptococcus species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, leprosy, plasmodium, toxoplasmosis, and Lyme disease [14–21].

Based on the presence of IgM and IgG antibodies to E. chaffeensis in the cryoprecipitate, we propose that the mixed cryoglobulinemia was induced by an immune response to ehrlichiosis. The absence of immunostaining of the kidney biopsy tissue for Ehrlichia does not preclude that diagnosis. In hepatitis C-related mixed cryoglobulinemia, the hepatitis C antigen may not be present in the kidney. Sansonno et al. [22] reported negative staining for hepatitis C proteins in 4 of 12 patients with documented hepatitis C-related cryoglobulinemia and MPGN. Thus, the findings in our patient suggest that ehrlichiosis should be added to the list of infections associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia and secondary MPGN.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:261–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salinas LJ, Greenfield RA, Little SE, Voskuhl GW. Tickborne infections in the southern United States. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:194–201. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e93817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paddock CD, Childs JE. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prototypical emerging pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:37–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.37-64.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Codner EC, Caceci T, Saunders GK, Smith CA, Robertson JL, Martin RA, Troy GC. Investigation of glomerular lesions in dogs with acute experimentally induced Ehrlichia canis infection. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codner EC, Maslin WR. Investigation of renal protein loss in dogs with acute experimentally induced Ehrlichia canis infection. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rooney TB, McGue TE, Delahanty KC. A naval academy midshipman with ehrlichiosis after summer field exercises in quantico, virginia. Mil Med. 2001;166:191–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scaglia F, Vogler LB, Hymes LC, Maki A., Jr Minimal change nephrotic syndrome: a possible complication of ehrlichiosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:600–601. doi: 10.1007/s004670050666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavares MB, Chagas de Almeida Mda C, Martins RT, de Sousa AC, Martinelli R, dos-Santos WL. Acute tubular necrosis and renal failure in patients with glomerular disease. Ren Fail. 2012;34:1252–1257. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.723582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esson ML, Schrier RW. Diagnosis and treatment of acute tubular necrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:744–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1108178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferri C. Mixed cryoglobulinemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, Bosch X. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet. 2012;379:348–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matignon M, Cacoub P, Colombat M, Saadoun D, Brocheriou I, Mougenot B, Roudot-Thoraval F, Vanhille P, Moranne O, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Fermand JP, Fakhouri F, Ronco P, Plaisier E, Grimbert P. Clinical and morphologic spectrum of renal involvement in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia without evidence of hepatitis c virus infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:341–348. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181c1750f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liou YT, Huang JL, Ou LS, Lin YH, Yu KH, Luo SF, Ho HH, Liou LB, Yeh KW. Comparison of cryoglobulinemia in children and adults. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genet P, Courdavault L, Wifaq B, Gerbe J. Symptomatic mixed cryoglobulinemia during hiv primary infection: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2011;2011:525841. doi: 10.1155/2011/525841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal A, Clements J, Sedmak DD, Imler D, Nahman NS, Jr, Orsinelli DA, Hebert LA. Subacute bacterial endocarditis masquerading as type iii essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1971–1976. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8121971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teruel JL, Matesanz R, Mampaso F, Lamas S, Herrero JA, Ortuno J. Pulmonary tuberculosis, cryoglobulinemia and immunecomplex glomerulonephritis. Clin Nephrol. 1987;27:48–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iveson JM, McDougall AC, Leathem AJ, Harris HJ. Lepromatous leprosy presenting with polyarthritis, myositis, and immune-complex glomerulonephritis. Br Med J. 1975;3:619–621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5984.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegler JL. Hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miralles Lopez JC, Lopez Andreu FR, Sanchez-Gascon F, Lopez Rodriguez C, Negro Alvarez JM. Cold urticaria associated with acute serologic toxoplasmosis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2005;33:172–174. doi: 10.1157/13075702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider CA, Jӧrg W, Seibt-Meisch S, Brückner W, Amann K, Scherberich JE. Borellia and nephropathy: cryoglobulinaemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis responsive to doxyclyclin in active lyme disease. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:77–80. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfs149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sansonno D, Gesualdo L, Manno C, Schena FP, Dammacco F. Hepatitis c virus-related proteins in kidney tissue from hepatitis c virus-infected patients with cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Hepatology. 1997;25:1237–1244. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]