Abstract

We describe a case of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) followed by pulmonary hemorrhage associated with Henoch-Schöenlein purpura (HSP) in an adult female. The patient had a history of renal insufficiency and persistent hematuria and proteinuria, without any extra-renal involvement. She was diagnosed with IgAN 7 years before the onset of HSP and had received immunosuppressive therapy for 6 years. One year after discontinuing oral prednisolone and mizoribine, she suffered a pulmonary hemorrhage. She presented with exacerbated urinary findings, and palpable purpura, resulting in the diagnosis of HSP. Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) and a monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse resolved the pulmonary hemorrhage. In a review of 36 HSP patients complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage, 27.8 % of the patients perished [Rajagopala et al., Semin Arthritis Rheum 42:391–400, 1]. While the most efficient therapeutic strategies for these patients have yet to be determined, we speculate that an aggressive therapy of pulse methylprednisolone combined with immunosuppression agents is likely to bring about the best outcome in cases with pathological conditions similar to our patient’s. On the other hand, discontinuance of immunosuppressive therapy might have resulted in the aggravation of the disease, hence we should examine patients carefully not to miss the cue.

Keywords: Pulmonary hemorrhage, Henoch-Schöenlein purpura, IgA nephropathy

Introduction

We present an adult case of Henoch-Schöenlein purpura (HSP) complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage, primary diagnosed of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) 7 years before the onset of HSP. The clinical manifestations and epidemiology of IgAN and HSP differ in some ways, but they are thought to be different clinical manifestations of the same disease as they share identical pathological and biological abnormalities [2]. No established treatment for pulmonary hemorrhage in HSP has been described in the literature, while patients receiving pulse methylprednisolone in combination with an immunosuppressive agent had lower mortality than steroid therapy alone in the review by Rajagopala et al. [1]. Thus, pulse methylprednisolone and an immunosuppressive agent may be the best regimen available for pulmonary hemorrhage associated with HSP, but further studies are required to define the optimal clinical strategy.

Case report

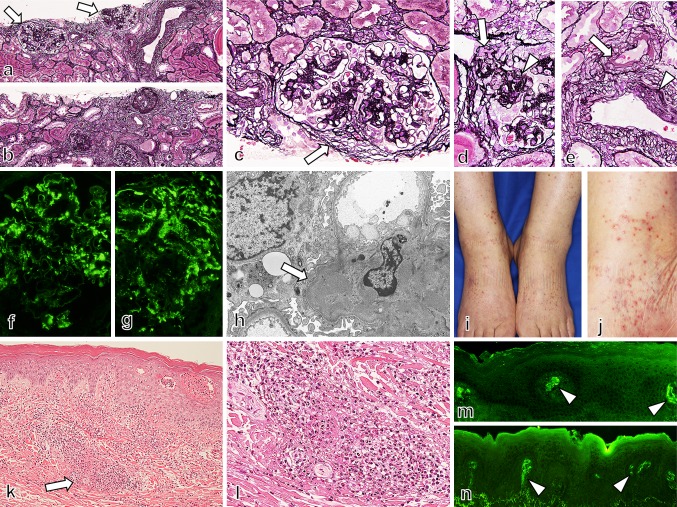

A 75-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital in February 2013 with a 2-week history of skin rash and leg edema in her lower extremities. She did not experience any symptoms that would result from antecedent infections, such as common cold. She began to experience dyspnea and hemoptysis 2 h before her admission, and she was hospitalized emergently. In 2006, 7 year before the onset of hemoptysis and skin rash, she presented with renal insufficiency, hematuria, and proteinuria without any extra-renal involvements. Laboratory findings at that time were as follows; serum urea, 36.2 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.99 mg/dL; C-reactive protein (CRP), 1.75 mg/dL; and IgA, 501 mg/dL. In the urinalysis, 290 mg/dL of protein was measured, the daily urinary protein excretion was 4.47 g/g·cr, and more than 100 red blood cells were counted per high-power field. Renal biopsy was performed, the samples included 18 glomeruli, and 8–10 glomeruli revealed obsolescence with tubulointerstitial lesion in 40 % of renal cortex (Fig. 1a, b). The other all glomeruli showed mild to moderate proliferative lesions with adhesion to Bowman’s capsule (Fig. 1c). Segmental sclerosis was noted in 2–4 glomeruli with fibrocellular crescent in one glomerulus (Fig 1d). The other one had fibrous crescent. There was no evidence of necrotizing lesion and cellular crescent in glomeruli. Besides, moderate intimal thickening and moderate hyalinosis were noted in interlobular arteries and small arterioles, respectively (Fig. 1e). Immunofluorescence study indicated the deposition of mesangial IgA and C3 (Fig. 1f, g). Electron microscopy showed mesangial electron dense deposits (Fig 1h). Based on these findings, we diagnosed IgA nephropathy, M1, E0, S1, T1 in Oxford classification, and histological grade IIIA/C in Japanese classification. In ensuing years she was treated with oral prednisolone and mizoribine. Here renal insufficiency progressed mildly and proteinuria was persistent, but hematuria and CRP both turned negative. Immunosuppressive therapy was terminated in February 2012; laboratory data at that moment was as follows: serum creatinine, 2.34 mg/dL; and C-reactive protein (CRP), 0.06 mg/dL. In the urinalysis, 131 mg/dL of protein was measured, the daily urinary protein excretion was 2.24 g/g·cr, and no blood cells were counted per high-power field. Since then, low-grade elevation of CRP was observed with no exacerbation of renal insufficiency or hematuria. On July 2012, and December 2012, Serum creatinine was 2.71, 2.48 mg/dL, and CRP was 2.68, 0.90 mg/dL, respectively. In the urinalysis, hematuria did not turn positive and the degree of proteinuria did not change.

Fig. 1.

In renal biopsy samples (a–h), 18 glomeruli were included, and 8–10 of them were obsolescence with tubulointerstitial lesion in 40 % of renal cortex (a, b). Segmental moderate proliferative lesions were noted with small fibrous crescent (c). Segmental sclerosis was also seen with small fibrocellular crescent (d). Small arteries showed moderate arterial hyalinosis and intimal hyperplasia (e). Immunofluorescence study showed the deposition of IgA (f) and C3 (g) in glomeruli, as mesangial granular pattern. Electron microscopy showed mesangial electron dense deposits in glomeruli (h). We therefore diagnosed as IgA nephropathy, M1, E0, S1, T1 in Oxford classification, and histological grade III A/C in Japanese classification. On admission, palpable purpura was observed on her lower extremities, and the purpuric rashes were 3–10 mm in diameter and associated with hemorrhagic vesicles (i, j). The skin biopsy specimen have shown leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the small vessels throughout the dermis (k, l), with IgA (m) and C3 (n) deposition in immunofluorescence study

Table 1.

Initial laboratory data and urinalysis at presentation

| Laboratory data | Blood gas analysis | ||

| TP (mg/dL) | 5.9 | pH | 7.275 |

| Alb (mg/dL) | 3.0 | PaCO2 (Torr) | 30 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 4.76 | PaO2 (Torr) | 74.4 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 100.2 | Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 13.6 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 141 | Aniongap (mEq/L) | 12.4 |

| K (mEq/L) | 5.9 | ||

| Cl (mEq/L) | 115 | Urinalysis | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10 | Specific gravity | 1.013 |

| WBC (μL) | 8000 | pH | 5 |

| Plt (×104/μL) | 12.3 | Protein (mg/dL) | 326 |

| ANA | <40 | UP (g/g·cr) | 5.04 |

| dsDNA (IU/mL) | 10 | Glucose | Negative |

| MPO-ANCA (EU) | <10 | Blood (hpf) | Strong positive |

| PR3-ANCA (EU) | <10 | Leukocyte (hpf) | Small |

| Anti-GBMA (EU) | <10 | Nitrites | Negative |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative | Bacteria | Negative |

| CH50 (U/mL) | 41.4 | Red blood cells (hpf) | 50–99 |

| C3 (mg/dL) | 86 | White blood cells (hpf) | 10–19 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 26 | Hyaline cast (hpf) | 10–19 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1220 | Granular cast (hpf) | 100> |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 642 | Waxy cast (hpf) | 30–49 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.5 | Epithelial cast (hpf) | 10–19 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1376.1 | Red blood cast | Negative |

TP total protein, Alb albumin, Cr creatinine, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Hb hemoglobin, WBC white blood cells, Plt platelets, ANA antinuclear antibody, c-ANCA proteinase-3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, p-ANCA myeloperoxidase-specific ANCA, Anti-GBMA anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody, CRP C-reactive protein, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, UP urinary protein

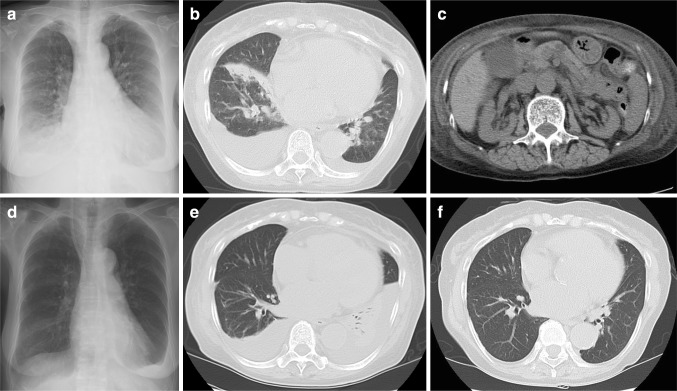

On admission, vital signs on physical examination were a temperature of 36.3 °C, heart rate of 75 beats per minute, and blood pressure of 162/88 mmHg. She repeatedly coughed up fresh bloody sputum, and palpebral conjunctiva was anemic. No murmur was detected in chest auscultation, but coarse crackles were audible in bilateral lower lung fields. Edemas and isolated clusters of palpable purpura were observed on her lower extremities (Fig. 1i, j). In a skin biopsy specimen from the patient’s right lower leg, leukocytoclastic vasculitis was observed in the small vessels throughout the dermis (Fig. 1k–n). Laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count, 8000/mm3; hemoglobin, 10.0 g/dL; platelet count, 12.3 × 104/mm3; sodium, 141 mEq/L; potassium, 5.9 mEq/L; chloride, 115 mEq/L; albumin, 3.0 g/dL; serum urea, 100.2 mg/dL; creatinine, 4.76 mg/dL; C-reactive protein (CRP), 2.50 mg/dL, BNP, 1376.1 pg/mL; serum immunoglobulin (Ig)G, 1220 mg/dL; and IgA, 642 mg/dL (normal range 110–410). C3, C4, and CH50 levels were normal. ANA, anti-dsDNA, proteinase-3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (PR3-ANCA), and myeloperoxidase-specific ANCA (MPO-ANCA) were all negative. IF (Immunofluorescence)-ANCA was also negative. Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody and cryoglobulins were also negative. Blood gas analysis revealed uncompensated acidosis (room air); pH, 7.275; PaCO2, 30.0 Torr; PaO2, 74.4 Torr; bicarbonate, 13.6 mmol/L; anion gap, 12.4 mEq/L. In the urinalysis, 326 mg/dL of protein was measured and 50–99 red blood cells were counted per high-power field (Table 1). Cardiomegaly, lung congestion, and bilateral pleural effusion with basal pulmonary infiltrates were observed on chest X-ray (Fig. 2a). A chest CT scan revealed diffuse consolidation and patchy opacities predominantly on the right lung fields without interstitial thickening or fibrosis (Fig. 2b). An abdominal CT scan have shown bilateral renal atrophy, ascites, and subcutaneous edema, thus we have decided not to perform second renal biopsy (Fig. 2c). The electrocardiogram on admission revealed left ventricular hypertrophy. The result of an echocardiography was as follows; ejection fraction of 79 %, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, dilation of left atrium, and no evidence of wall motion deficiency. Considering the echocardiography findings, it came to a conclusion that her cardiac failure resulted from plethora by renal failure resulting in an acute exacerbation of hypertensive heart disease.

Fig. 2.

On admission, cardiomegaly, lung congestion, and bilateral pleural effusion with basal pulmonary infiltrates were observed on chest X-ray (a). Chest CT scan revealed diffuse consolidation and patchy opacities predominantly on the right lung fields (b). An abdominal CT scan has shown bilateral renal atrophy, ascites, and subcutaneous edema (c). Follow-up survey of chest X-ray and CT images has shown remission of the right sided lower lung field diffuse consolidation, although bilateral pleural effusion and atelectasis worsened (d, e). The exacerbation of pleural effusion and atelectasis drastically improved after discharge from hospital (f)

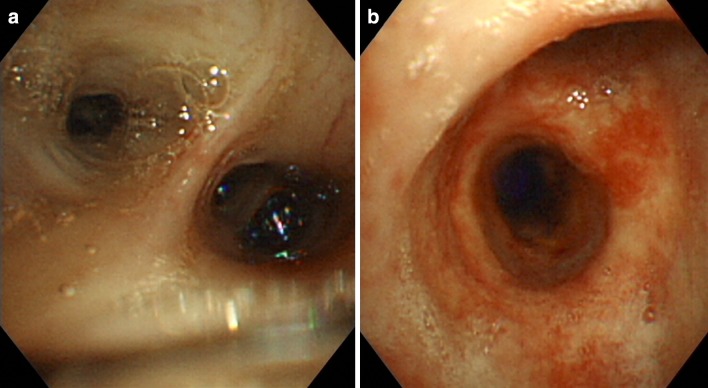

One day after admission, blood clots in the right main primary bronchus of the trachea were observed by bronchoscopy (Fig. 3a, b), and progressive worsening of bloody drainage, a finding specific to pulmonary hemorrhage, was observed in BAL (broncho-alveolar lavage). Upper endoscopy examination was intact, and occult blood tests were also negative. The diagnosis of pulmonary hemorrhage associated with Henoch-Schöenlein purpura (HSP) was based on laboratory findings, and skin biopsy. The immunosuppression therapy regimen was administered from the second hospital day. The patient received methylprednisolone sodium succinate at a dose of 500 mg/day for 3 days, followed by oral prednisolone (45 mg/day; 1 mg/kg/day). We did not administrate antibiotics, and none of the sputum cultures turned positive. Her hemoptysis stopped just after an introduction of immunosuppression therapy. Skin rash and hematuria diminished soon after the immunosuppressive therapy, but oliguria and serum creatinine did not recover. Hemodialysis was commenced on the third hospital day because of acute exacerbation of the renal dysfunction, and the patient was given oxygen and a transfusion of 2 units of blood because of anemia and cardiac failure. The administration of hemodialysis also resulted in draining excessive body fluid and relieved symptoms of cardiac failure. Her general condition stayed stable, but low-grade elevation of CRP (0.5–3 mg/dL) was observed as steroids have been tapered, indicating an importance to maintain effective immune suppression. In addition, the patient had a history of steroid osteoporosis, and femoral neck fracture. Thus, we needed to taper steroid promptly to avoid further side effects. We have decided to introduce monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy on the 21st hospital day at a reduced dose of 350 mg/day (7.5 mg/kg) in consideration of the patient’s renal dysfunction. The dose of oral prednisolone was reduced to 5 mg per week. Follow-up survey of chest X-ray and CT images have shown remission of the right sided lower lung field diffuse consolidation, although bilateral pleural effusion and atelectasis worsened (Fig. 2d, e). The exacerbation of pleural effusion and atelectasis seemed to have resulted from the bed rest and the depression of serum albumin level, as these findings drastically improved after discharge from hospital (Fig. 2f). Oral prednisolone was tapered to 15 mg/day, and the patient was discharged on the 60th hospital day. Monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy was repeated four times and she is well, taking maintenance dose of 5 mg/day prednisolone and hemodialysis.

Fig. 3.

One day after admission, bronchoscopy was performed to find blood clots in the right main primary bronchus of the trachea (a, b), and the progressive aggravation of bloody drainage which is a specific finding to pulmonary hemorrhage was observed in BAL (Figure not shown)

Discussion

We reported an adult case of HSP complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage. She had presented with renal insufficiency, hematuria, and proteinuria 7 years before the onset of HSP. A renal biopsy at that time revealed mainly focal and segmental mesangial proliferation. Matrix expansion was observed in light microscopy, and mesangial accumulation of IgA associated with less intense deposits of IgM and C3 was observed in immunofluorescence. No extra-renal involvement was detected, so the patient was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy (IgAN). For the next 6 years (2006–2012) she was kept on immunosuppressive therapy. Her pulmonary hemorrhage took place about 1 year after the oral prednisolone and mizoribine were discontinued. Recurrent hematuria, exacerbated proteinuria, and palpable purpura on her lower extremities at presentation indicated systemic vasculitis. Laboratory data indicated elevated levels of CRP and IgA (2.50–642 mg/dL), but ANA, anti-dsDNA, PR3-ANCA, MPO-ANCA, and Anti-GBM antibodies were all negative. Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, a condition that supported the diagnosis of HSP as the cause of her pulmonary hemorrhage. Pulmonary hemorrhage is extremely rare as a complication of HSP: according to the literature: only 36 cases have been reported [1].

HSP is usually a self-limited condition that lasts about 4 weeks [3, 4]. The major manifestations are purpura, arthritis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and nephritis [3, 4]. Nephritis rarely if ever precedes the onset of purpura in HSP, in fact, the onset of nephritis may be delayed for weeks or months after the appearance of other symptoms [2, 3, 5–7].

IgAN is a chronic disease presenting with microscopic hematuria and/or proteinuria, and renal dysfunction without extra-renal involvement. The clinical manifestations of IgAN partly differ from those of HSP, but the two diseases are thought to be related since they share identical pathological and biological abnormalities [2]. When Baart de la Faille-Kuyper et al. [8] investigated the vessels and connective tissue of clinically uninvolved skin of IgAN patients, they found that IgA deposits were accompanied by C3 in the cutaneous capillary walls of 33 out of 36 patients. There have also been cases presenting initially with IgAN followed by the classical clinical course of HSP [9–13], and other cases in identical twins [14]. Given those close pathological and clinical associations of IgAN and HSPN, some researchers surmise that IgAN and HSP are different clinical manifestations of the same disease, sharing a common pathogenesis [2, 12, 13]. Although it is said that nephritis rarely precede the onset of purpura in HSP [2, 3, 5–7], HSP without any extra-renal involvements can never be diagnosed HSP but IgAN by pathological and clinical findings at the time of diagnosis. CRP titer was positive when first diagnosis of IgAN had been made, while IgAN is usually not accompanied by CRP elevation. This implies that she might have had the factor of vasculitis from the beginning of the clinical course, which makes it more reasonable to assume that primary nephritis and HSP are closely correlated. Thus we believe that our patient was initially diagnosed IgAN and developed HSP 7 years later by the same pathophysiological disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first case report presenting a biopsy-proven IgAN followed by pulmonary hemorrhage associated with HSP.

Rajagopala et al. [1] reviewed 36 cases of HSP complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage, the only known cases reported in the English-language literature. Among those patients, 50 % were older than 20 years at presentation, 94.4 % manifested renal vasculitis, and as many as 27.8 % died [1]. Apart from the HSP patients with pulmonary hemorrhage, former studies have shown HSP to be a predominantly pediatric disease affecting children between the ages of 4 and 7 years (prevalence of 70 per 100,000 in that age range) [4]. Other studies had already shown, however, that older HSP patients were prone to suffer from more severe disease [15, 16]. Our case was no exception (75 years old, complicated with CKD), and the findings overall suggest that older HSP patients need careful observation to detect complications not only of renal insufficiency, but also pulmonary hemorrhage.

No established treatment for pulmonary hemorrhage in HSP has been described in the literature. In HSP patients with nephritis, pulse methylprednisolone followed by oral corticosteroids plus azathioprine or cyclophosphamide effectively reverses clinical nephritis and prevents disease progression [3, 4]. Patients with pulmonary hemorrhage associated with HSP capillaritis are treated with a similar regimen [17]. In the review by Rajagopala et al. [1], 50 % of patients were receiving oral steroids at the time of pulmonary hemorrhage and 11 % had already taken methylprednisolone pulse therapy. A more intensive immunosuppressive therapy for systemic vasculitis would be of great benefit, as methylprednisolone pulse therapy alone and other steroids appear to be ineffective. Eleven patients receiving pulse methylprednisolone in combination with an immunosuppressive agent (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclosporine A) had for lower mortality (9 %; 1 out of 11 patients) than steroid therapy alone [1]. Our case was given pulse methylprednisolone at a dose of 500 mg/day in the first 3 days, followed by oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) and monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. The immunosuppressive therapy in this regimen brought about a rapid remission of pulmonary hemorrhage, and no signs of exacerbated vasculitis have been observed. Thus, pulse methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide may be the best regimen available for pulmonary hemorrhage associated with HSP, but further multicentric observational studies will be required to define the optimal clinical strategy.

Apart from the high incidence of recurrence and high morbidity, there has been no discussion of whether clinical findings can detect an exacerbation of the disease [1]. Laboratory findings on CRP, IgA, and hematuria from the 7-year follow-up of our case appear to provide useful parameters. The pulmonary hemorrhage took place about 1 year after the termination of a 6-year course of immunosuppressive therapy. Just after the therapy was terminated, elevated CRP and the presence of IgA were noted without any symptoms. Hematuria remained negative throughout the 6 years of immunosuppressive therapy, but recurred 2 weeks before onset of pulmonary hemorrhage. These parameters are considered to reflect systemic vasculitis, and all of them can be observed when pulmonary hemorrhage recurs. Other environmental exposures such as former respiratory infection and the season of the year (most patients present from autumn to spring) appear to be associated in some cases [3, 4]. In light of the high frequency of recurrence, we believe that more specific observational studies could contribute to the management of HSP complicated with pulmonary hemorrhage.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Rajagopala S, Shobha V, Devaraj U, D’Souza G, Garg I. Pulmonary hemorrhage in henoch-schonlein purpura. Case report and systematic review of the English literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davin JC, Ten Berge IJ, Weening JJ. What is the difference between IgA nephropathy and Henoch-schönlein purpura nephritis? Kidney Int. 2001;59:823–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059003823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saulsbury FT. Clinical update: Henoch-schonlein purpura. Lancet. 2007;369:976–978. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:35–40. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-schönlein purpura in children. Report of 100 patients and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:395–409. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calviño MC, Llorca J, García-Porrúa C, Fernández-Iglesias JL, Rodriguez-Ledo P, González-Gay MA. Henoch-schönlein purpura in children from northwestern spain: a 20-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Medicine. 2001;80:279–290. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trapani S, Micheli A, Grisolia F, Resti M, Chiappini E, Falcini F, De Martino M. Henoch-schönlein purpura in childhood: epidemiological and clinical analysis of 150 cases over a 5-year period and review of literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faille-Kuyper EH, Kater L, Kuijten RH, Kooiker CJ, Wagenaar SS, van der Zouwen P, Mees EJ. Occurrence of vascular IgA deposits in clinically normal skin of patients with renal disease. Kidney Int. 1976;9:424–429. doi: 10.1038/ki.1976.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravelli A, Carnevale-Maffe G, Ruperto N, Ascari E, Martini A. IgA nephropathy and Henoch-schönlein syndrome occurring in the same patient. Nephron. 1996;72:111–112. doi: 10.1159/000188822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamoto Y, Asano Y, Dohi K, Fujioka M, Iida H, Kida H, Kibe Y, Hattori N, Takeuchi J. Primary IgA glomerulonephritis and Schönlein-Henoch purpura nephritis. Clinicopathological and immunohistological characteristics. Q J Med. 1978;47:495–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes FJ, Wolfish NM, McLaine PN. Henoch-schönlein syndrome and IgA nephropathy: a case report suggesting a common pathogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1988;2:389–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00853426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chishiki M, Kawasaki Y, Kaneko M, Ushijima Y, Ohara S, Abe Y, Suyama K, Hashimoto K, Hosoya M. A 10-year-old girl with IgA nephropathy who 5 years later developed the characteristic features of Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2010;56:157–161. doi: 10.5387/fms.56.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paynter HE, Banks RA. Evolution of IgA nephropathy into Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an adult. Clin Nephrol. 1998;49:121–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meadow SR, Scott DG. Berger disease: Henoch-Schönlein syndrome without the rash. J Pediatr. 1985;106:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(85)80459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, Wang LC, Lee JH, Chiang BL. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162–168. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronkainen J, Nuutinen M, Koskimies O. The adult kidney 24 years after childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360:666–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ioachimescu OC, Stoller JK. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: diagnosing it and finding the cause. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:255–264. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.4.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]