Abstract

Although diabetic nephropathy is a microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, some reports suggest that renal biopsy often shows this pathological change without a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Here, we report a case of a 65-year-old man who presented with proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and hypertension without a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. He drank alcohol regularly and was a heavy smoker. Renal biopsy revealed a diffuse increase in the mesangial area, mesangial nodules or well-developed hyalinosis, interstitial fibrosis, and arteriosclerosis consistent with the changes of diabetic nephropathy. Although we had initially diagnosed him with idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis, use of a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) revealed that the changes in his daily blood glucose concentrations met with the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. Accordingly, we diagnosed him with diabetic nephropathy and initiated treatment for diabetes mellitus. This case suggests that some cases of diabetic nephropathy may be hidden among patients with impaired glucose tolerance, who are not diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. Use of a CGMS may be helpful in diagnosing this type of “hidden” diabetes mellitus. In addition to diet therapy, smoking control, treatment for hypertension, and strict control of hyperglycemia may be important for these patients.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis, Glucose tolerance, Hyperglycemia, Hypertension, Continuous glucose monitoring system

Introduction

Proteinuria is one of the principal features of diabetic nephropathy. Some reports suggest the existence of cases in which the pathological changes of diabetic nephropathy are observed without a diagnosis of overt diabetes mellitus [1–3]. These patients are diagnosed with idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis (ING). Strict control of smoking and hypertension, which are known causes of ING, is thought to be more effective treatments for this disorder than glycemic control. Recently, a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) has been used to provide more detailed information about the changes in daily blood glucose concentrations. Here, we report our experience of a case of diabetic nephropathy initially suspected based on the results of renal biopsy, and finally diagnosed using a CGMS.

Case report

A 65-year-old Japanese man presented with proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia. His family and medical history were unremarkable except for impaired glucose intolerance (IGT), which had been identified several years previously; however, the patient could not recall exactly when and unfortunately, his medical records were unavailable. At that time, he had received a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) but was not diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. He reported a regular intake of alcohol (350 ml beer and 180 ml distilled liquor every day) and was a heavy smoker (20 cigarettes a day for more than 40 years).

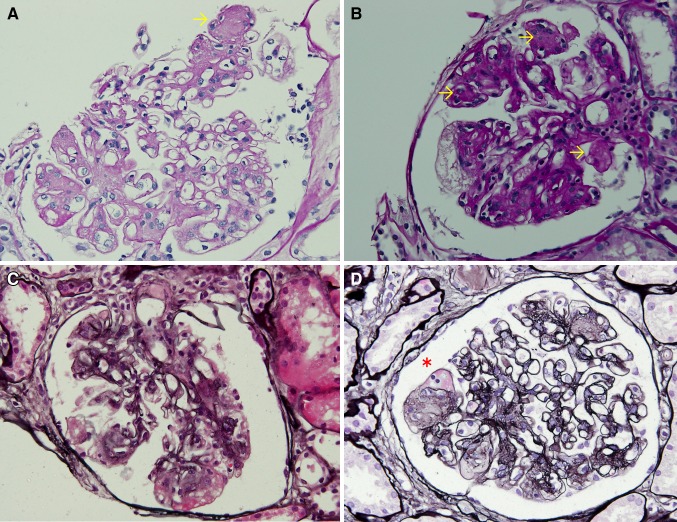

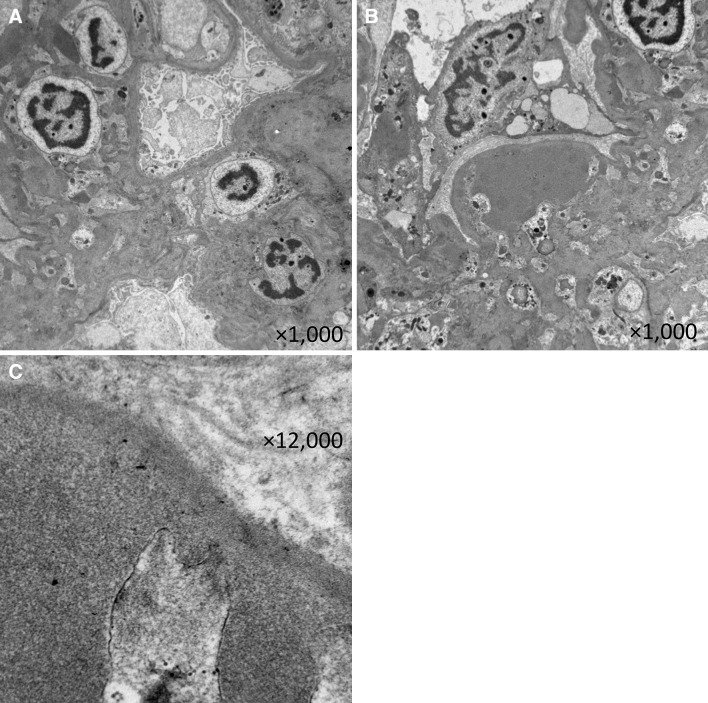

His height was 180 cm and body weight was 75 kg. His blood pressure was 161/89 mmHg. Physical examination showed bilateral leg mild pitting edema. His laboratory test results were: white blood cell count 9,200/μL, hemoglobin 15.7 g/dL, platelets 159 × 104/μL, serum total protein 5.9 g/dL, serum albumin 3.1 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL, serum creatinine 1.02 mg/dL, total cholesterol 221 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol 51 mg/dL, triglyceride 183 mg/dL, postprandial blood glucose 122 mg/dL, and HbA1c 5.6 %. His serum immunoglobulin and complement levels were within normal limits. Anti-nuclear antibodies, proteinase-3 (PR3)-ANCA, and myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA were negative. Tests for hepatitis B virus surface antigen and antibodies against hepatitis C virus were also negative. Urinalysis revealed 2 + protein, and negative for occult blood and sugar. Urinary sedimentation showed 5–9 erythrocytes and 1–4 leukocytes per high-power microscope field. Urinary protein excretion was 1.8 g/day. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis did not reveal anything significant. There were no significant findings from his electrocardiogram and chest radiograph. The abdominal computed tomography and ultrasonography revealed some small kidney stones and no size changes of the bilateral kidneys (right kidney length, 112.7 mm; left kidney length, 128.1 mm). Renal biopsy was performed and evaluation by light microscopy revealed 13 glomeruli, two of which were globally sclerotic. The remaining glomeruli showed diffuse increases in the amount of mesangial matrix and the number of mesangial cells, some small mesangial nodules, mild interstitial fibrosis, hyaline vascular sclerosis and a fibrin cap (Fig. 1). No amyloid accumulation was observed following Congo red staining. Immunofluorescent staining showed non-specific staining for C3 around the vascular walls, while staining for IgG, IgM, IgA and fibrinogen was negative. Electron microscopy showed an increase in the mesangial matrix, which contained hyalinosis lesions although amyloid fibers were not revealed (Fig. 2). We performed additional examinations for diabetes mellitus. A 75 g OGTT showed a fasting plasma glucose concentration of 106 mg/dL; the first and second hour plasma glucose concentrations were 203 and 190 mg/dL, respectively. Wide-field laser ophthalmoscopy (not fluorescein angiography) did not show any changes typical of diabetic retinopathy or hypertensive retinopathy. Physical examination, nerve conduction studies and coefficient of variation of R–R intervals (CVR-R) did not show any specific findings typical of diabetic neuropathy. Use of a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS; iPro2®; Medtronic MiniMed, Northridge, CA, USA) revealed continuous hyperglycemia and repeated postprandial hyperglycemia (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

a, b PAS-stained glomerulus showing mesangial matrix increase and nodule formation (arrows). c PAM-stained glomerulus showing hyaline vascular sclerosis. d PAM-stained glomerulus showing fibrin cap (asterisk)

Fig. 2.

Electron microscopy showing increase in mesangial matrix (a) and hyalinosis lesion in a capillary loop without amyloid fibers (b, c)

Fig. 3.

CGMS showing normal fasting blood glucose and hidden hyperglycemia especially detected after breakfast. Interestingly, there are few points indicating a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL)

Discussion

The pathological features of diabetic nephropathy are nodular or diffuse glomerulosclerosis; however, pathological findings similar to diabetic nephropathy are occasionally observed in the absence of diabetes mellitus [1–3]. Similar nodular changes are seen in amyloidosis, light chain deposit disease, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), and Takayasu’s arteritis. These pathological changes without underlying diseases are referred to as idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis (ING). There are several reports that hypertension and smoking increase the risk of ING [4, 5], both of which were risk factors in this patient. In this case, amyloidosis and light chain deposit disease were unlikely based on the results of protein electrophoresis and renal biopsy in addition to the absence of specific clinical features. There were also no clinical features, which suggested Takayasu’s arteritis. This patient has hypertension and a heavy smoking habit. Although the 75 g OGTT revealed impaired glucose intolerance, we initially diagnosed the patient as ING because the criteria for diabetes mellitus were not met and neither diabetic retinopathy nor diabetic neuropathy was detected. However, use of a CGMS revealed the existence of hyperglycemia consistent with diabetic diagnostic criteria and we finally diagnosed the patient with diabetic nephropathy. Dietary intervention was initiated (low sodium and low protein), in combination with smoking control, and medication comprising an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (telmisartan) and a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor (sitagliptin). Makino at el. suggest that telmisartan suppresses the progression of diabetic nephropathy from incipient to overt proteinuria [6]. Furthermore, several reports show that sitagliptin improves glycemic control and produces small reductions in blood pressure [7, 8]. Although the patient’s kidney function and proteinuria did not worsen, his proteinuria remained at 1.0–2.0 g/day 1 year later.

Diabetic nephropathy is caused by many factors [9], and in this case, we speculated that his repeated postprandial hyperglycemia, hypertension, and heavy smoking had contributed to the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is thought to cause cellular injury in the kidney. Interestingly there are some reports that methylglyoxal (MG), an α-oxoaldehyde-derived precursor of AGEs, is closely related to postprandial hyperglycemia and may be a HbA1c-independent risk factor for diabetic angiopathy [10]. Hypertension contributes to the progression of diabetic nephropathy by further increasing the intraglomerular pressure and exacerbating kidney damage. It has been suggested that anatomical structures of the renal vasculature, which arise from either the initial segment of the interlobular artery or directly from the arcuate artery (strain vessel), lead to diabetic nephropathy without causing diabetic retinopathy and neuropathy, although this remains to be confirmed [11]. Smoking causes kidney damage due to the oxidative stress mediated by AGEs and hypertension mediates stimulation of sympathetic nerve activity [4, 12]. We believe that these factors contributed to the diabetic changes in the glomeruli observed in this case.

In previous reports, it has been suggested that diabetic nephropathy and ING are similar yet different concepts of disease. Previous reports, however, suggest that diabetes mellitus, hypertension and smoking contribute to kidney disorders via some common pathways. Diabetes mellitus, including postprandial hyperglycemia, and smoking, may cause damage to the glomeruli by common pathways, for example, that of AGEs [4, 10, 12], dysregulation of intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 expressed by vascular endothelial cells [13–16] and increasing the expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), an profibrotic cytokine [17, 18]. It is difficult to distinguish diabetic nephropathy from ING except by speculation based on the clinical course. However, new CGMS technology provides detailed information of fluctuations in blood glucose concentrations over time, thus facilitating early diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. There are currently no reports describing the use of CGMS technology for the diagnosis of simultaneous diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. This case suggests that some cases of diabetic nephropathy are “hidden” among the IGT patients not diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and strict control of hyperglycemia, in addition to other treatments for nephropathy, are important for such patients, and the use of a CGMS may aid in the diagnosis of hidden diabetes mellitus. Although this patient did not recover from overt to incipient proteinuria, the information obtained in this case using CGMS technology may benefit other similar patients by facilitating the early and exact diagnosis and treatment of diabetes mellitus.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Chan JY, Cole E, Hanna AK. Diabetic nephropathy and proliferative retinopathy with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 1985;8:385–390. doi: 10.2337/diacare.8.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida A, Morozumi K, Oikawa T, Suganuma T, Aoki J, Sugito K, Koyama K, Fujinami T, Shigematsu H. Nodular glomerulosclerosis in a patient showing impaired glucose tolerance. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1990;32:877–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altiparmak MR, Pamuk ON, Pamuk GE, Apaydin S, Ozbay G. Diffuse diabetic glomerulosclerosis in a patient with impaired glucose tolerance: report on a patient who later develops diabetes mellitus. Neth J Med. 2002;60:260–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowitz GS, Lin J, Valeri AM, Avila C, Nasr SH, D’Agati VD. Idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis is a distinct clinicopathologic entity linked to hypertension and smoking. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:826–835. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.126189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuppachi S, Idris N, Chander PN, Yoo J. Idiopathic nodular glomerulosclerosis in a non-diabetic hypertensive smoker: case report and review of literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3571–3575. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makino H, Haneda M, Babazono T, Moriya T, Ito S, Iwamoto Y, Kawamori R, Takeuchi M, Katayama S. INNOVATION study group. Prevention of transition from incipient to overt nephropathy with telmisartan in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1577–1578. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori Y, Taniguchi Y, Matsuura K, Sezaki K, Yokoyama J, Utsunomiya K. Effects of sitagliptin on 24-h glycemic changes in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes assessed using continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:699–703. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Liu J, Wong WT, Tian XY, Lau CW, Wang YX, Xu G, Pu Y, Zhu Z, Xu A, Lam KS, Chen ZY, Ng CF, Yao X, Huang Y. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor sitagliptin protects endothelial function in hypertension through a glucagon-like peptide 1-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2012;60:833–841. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.195115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall SM. Recent advances in diabetic nephropathy. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:624–633. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.021287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa S, Nakayama K, Nakayama M, Mori T, Matsushima M, Okamura M, Senda M, Nako K, Miyata T, Ito S. Methylglyoxal is a predictor in type 2 diabetic patients of intima-media thickening and elevation of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2010;56:471–476. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.156786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito S, Nagasawa T, Abe M, Mori T. Strain vessel hypothesis: a viewpoint for linkage of albuminuria and cerebro-cardiovascular risk. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:115–121. doi: 10.1038/hr.2008.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasr SH, D’Agati VD. Nodular glomerulosclerosis in the nondiabetic smoker. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2032–2036. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin J, Glynn RJ, Rifai N, Manson JE, Ridker PM, Nathan DM, Schaumberg DA. Inflammation and progressive nephropathy in type 1 diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2338–2343. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu HF, Ma J, Gu KT, Brismar K. Association of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) with diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;3:179. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann S, Siekmeier R, Mix C, Jaross W. Even moderate cigarette smoking influences the pattern of circulating monocytes and the concentration of sICAM-1. Respir Physiol. 1998;114:269–275. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(98)00098-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott DA, Stapleton JA, Wilson RF, Sutherland G, Palmer RM, Coward PY, Gustavsson G. Dramatic decline in circulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1 concentration on quitting tobacco smoking. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2000;26:255–258. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obert DM, Hua P, Pilkerton ME, Feng W, Jaimes EA. Environmental tobacco smoke furthers progression of diabetic nephropathy. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:126–130. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181f6e3bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziyadeh FN, Isono M, Chen S. Involvement of the transforming growth factor-β system in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2002;6:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s101570200021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]