Abstract

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) is one of the renal pathological manifestations of sarcoidosis. It is usually clinically silent, but may present occasionally as acute kidney injury (AKI). AKI caused by sarcoid GIN without extrarenal manifestations is extremely rare. We report a case of a 70-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus admitted with progressively worsening kidney function. The patient also exhibited anorexia, malaise and weight loss. Laboratory tests showed an elevated serum lysozyme level, but the serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and serum calcium levels were normal. Increased uptake was evident only in kidney on gallium 67 scintigraphy. Although typical organ involvement of sarcoidosis was not evident, a renal biopsy showed granulomatous interstitial nephritis with non-caseating granulomas. No medications had been added in the 3 years preceding renal function deterioration. Following a bronchoalveolar lavage that revealed a high CD4:CD8 ratio, and a skin test that showed negative for tuberculin, a diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis was established. On diagnosis, oral prednisolone was initiated and renal function improved. The anorexia and malaise also disappeared. This is the extremely rare case of AKI caused by sarcoid GIN without extrarenal manifestations or elevated serum ACE level.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, Acute kidney injury, Granulomatous interstitial nephritis

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease characterized by non-caseating granulomatous inflammation with tissue destruction [1]. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder that typically presents with pulmonary manifestations, and up to 30 % of patients present with extrapulmonary manifestations [2]. Several small series have suggested that renal involvement occurs in 35–50 % of sarcoidosis patients; hypercalciuria and hypercalcemia are most often responsible for clinically significant renal disease [3, 4]. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) is one of the renal pathological manifestations of sarcoidosis. It is usually clinically silent, but may present occasionally as acute kidney injury [5].

Several reports have described the clinical features and courses of patients suffering from sarcoidosis with renal impairment due to GIN [5–16], and most patients have also presented with extrarenal manifestations. Clinically important renal involvement without extrarenal symptoms is extremely rare in GIN with sarcoidosis. We report herein the case of a patient with acute kidney injury caused by isolated sarcoid GIN without hypercalcemia. The patient was successfully treated with oral steroid therapy.

Case report

A 70-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was referred to the Department of Nephrology in late April 2014 with rapidly decreasing renal function and malaise. Diabetes mellitus was well-controlled by lifestyle modification and medication, and no retinopathy was present. On referral, the patient had no other significant symptoms or clinical findings, including lymphadenopathy, skin rash, erythema nodosum or sinus tenderness. Neurological examination showed no abnormalities. He had been periodically followed by the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery after coronary artery bypass graft surgery for unstable angina pectoris performed in 2010. Medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, carvedilol, linagliptin and warfarin. All of these medications had been started at least 3 years before this referral. Until late January 2014, renal function had been stable and serum creatinine had remained at about 1.0 mg/dL (Fig. 1). However, from mid-February 2014, symptoms of anorexia and malaise started to manifest, and he lost 3 kg of body weight within only 2 months. By the end of April, serum creatinine had risen to 2.39 mg/dL, accompanied by proteinuria.

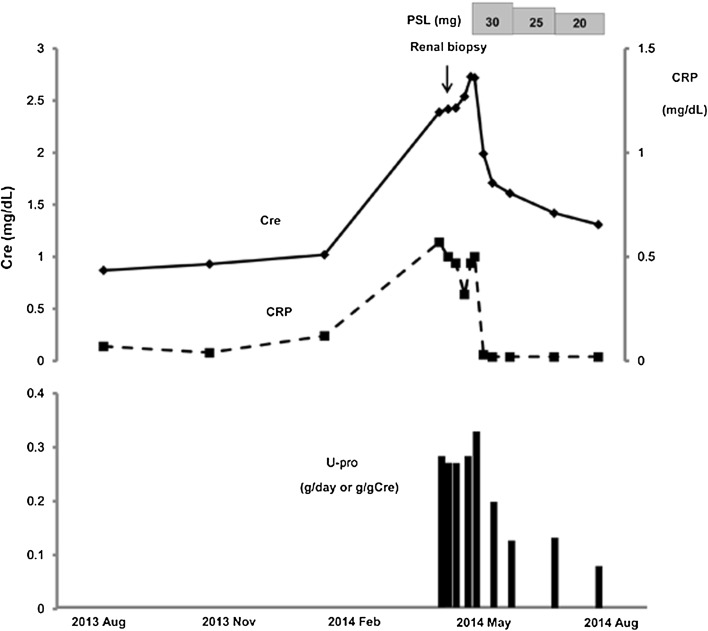

Fig. 1.

Clinical course of urine protein and serum creatinine and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Cre serum creatinine, g/gCr urinary protein to urinary creatinine ratio, U-pro urinary protein, PSL prednisolone

On referral, blood pressure was 155/83 mmHg. In addition to deteriorated renal function, laboratory examination revealed slightly elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum lysozyme levels greater than two times the upper limit of normal. However, serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and calcium were normal. Urinalysis showed dipstick proteinuria (1+), no hematuria, no white blood cells, and no dysmorphic red blood cells or casts. Urinary excretion of β2-microglobulin and N-acetylglucosaminidase was each markedly elevated (Table 1). Twenty-four-hour urinary excretion of calcium was normal. Negative results were obtained for anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and rheumatoid factor (Table 1). Ultrasonography showed normal-sized kidneys with normal echogenicity, and normal findings of his neck and abdomen. No evidence of urinary tract obstruction was identified. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) showed no enlargement of the hilar lymph nodes, no interstitial changes, and no mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary function testing showed normal vital capacity and normal percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1.0 s (FEV1.0%). Increased uptake was evident only in kidney on gallium 67 (67Ga) scintigraphy (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of tuberculosis, fungal infection, or malignancy. Ophthalmologic examination showed no uveitis.

Table 1.

Laboratory data at the time of referral to the Department of Nephrology

| Blood counts | Serology | ||

| White blood cells | 4600/μL | IgG | 1320 mg/dL |

| Neutrophils | 72.1 % | IgA | 150 mg/dL |

| Lymphocytes | 17.3 % | IgM | 72 mg/dL |

| Monocytes | 10 % | IgE | 33 IU/mL |

| Eosinophils | 0.4 % | CH50 | 60 CH50/mL |

| Basophils | 0.2 % | CRP | 0.53 mg/dL |

| Red blood cells | 368 × 104/μL | RF | <3 IU/mL |

| Hemoglobin | 11 g/dL | ANA | – |

| Platelets | 16 × 104/μL | P-ANCA | <10 EU |

| C-ANCA | <10 EU | ||

| Blood chemistry | ACE | 15.2 U/L | |

| Sodium | 144 mEq/L | Lysozyme | 23.7 μg/mL |

| Potassium | 4 mEq/L | Urinalysis | |

| Chloride | 109 mEq/L | Protein | 0.31 g/day |

| Calcium | 9.4 mg/dL | Occult blood | (1+) |

| Urea nitrogen | 32 mg/dL | Glucose | (−) |

| Creatinine | 2.38 mg/dL | Sediment (HPF) | |

| Total protein | 6.8 g/dL | RBC | 0–1 |

| Albumin | 3.9 g/dL | WBC | 0–1 |

| AST | 12 IU/L | Epithelial cast | 0–1 |

| ALT | 13 IU/L | Granular cast | (−) |

| Glucose | 104 mg/dL | ||

| T chol | 161 mg/dL | β2MG | 32,760 μg/L |

| LDL chol | 102 mg/dL | NAG | 22 U/L |

AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, T chol total cholesterol, LDL chol low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Ig immunoglobulin, CH50 50 % hemolytic complement unit, CRP C-reactive protein, RF rheumatoid factor, ANA anti-nuclear antibody, P-ANCA myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, C-ANCA serine proteinase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, ACE serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, RBC red blood cells, WBC white blood cells, β2MG β2-microglobulin, NAG N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase

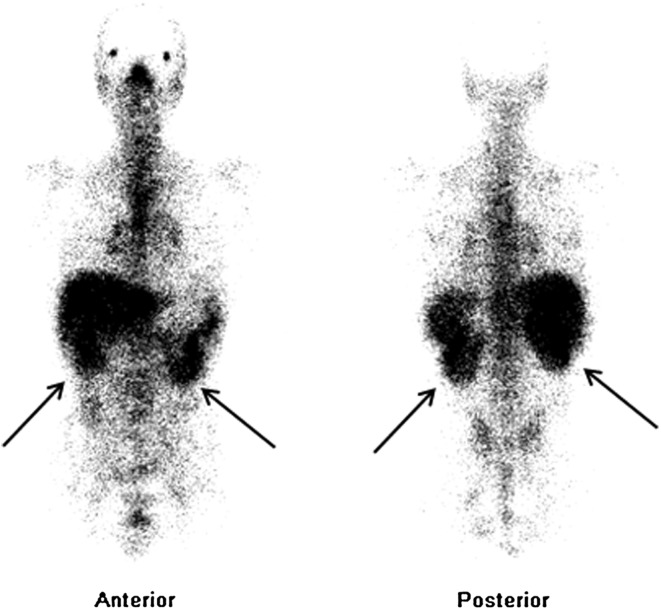

Fig. 2.

Gallium 67 (67Ga) scintigraphy showing increased uptake in kidney (black arrows)

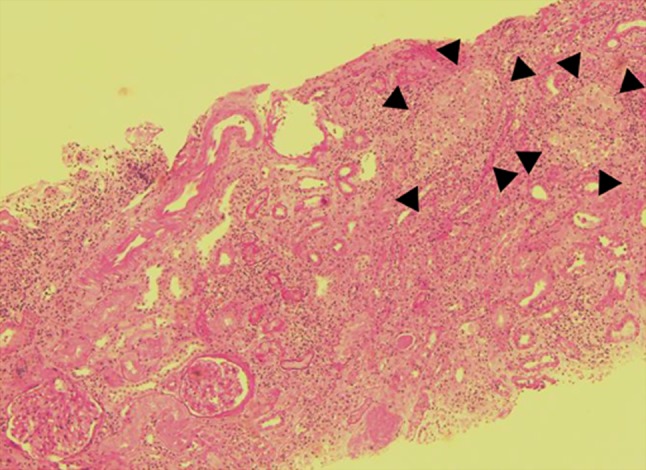

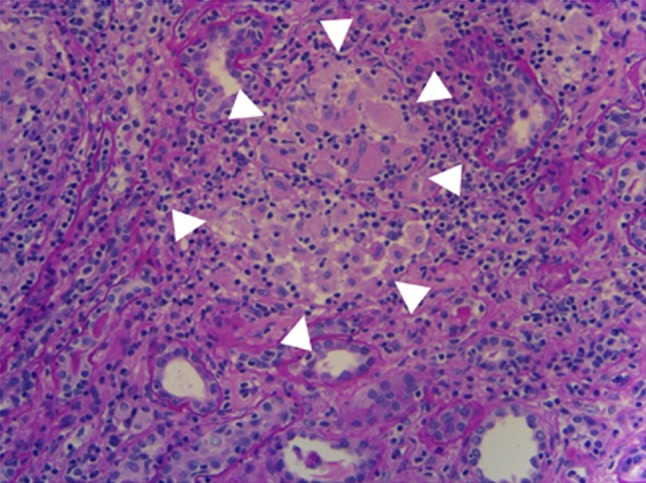

Renal biopsy was performed 1 week after referral to the Department of Nephrology for investigation of acute kidney injury. The biopsy specimens contained 16 glomeruli. Light microscopy showed three sclerotic glomeruli. The other glomeruli were almost normal, and no crescents were identified. Diabetic changes were not evident. In the interstitium, approximately 50 % of the renal cortex showed obvious mononuclear cell infiltration and non-caseating granulomas comprising epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes (Figs. 3, 4). Immunofluorescence showed no glomerular staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C4, or C1q. Electron microscopy showed local effacement of the glomerular foot processes without electron-dense deposits or basement membrane abnormalities. These pathological findings led us to a diagnosis of granulomatous interstitial nephritis.

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy showing two normal glomeruli, diffuse infiltration of renal interstitium by inflammatory cells, extensive tubular atrophy and several non-caseating granulomas (black arrowheads). Periodic acid–Schiff stain, ×50

Fig. 4.

Light microscopy showing non-caseating granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and monocytes (white arrowheads). Periodic acid–Schiff stain, ×200

Although no physical, laboratory or radiological findings except for elevated serum lysozyme level supported a diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis, the identification of granulomas in the kidney biopsy led us to perform additional tests to rule out sarcoidosis, including tuberculin skin testing and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Tuberculin skin test reactivity was negative, and bronchoscopy did not show ectasia of the capillary network. An elevated cluster of differentiation (CD)4:CD8 ratio of 6.4 was revealed on BAL. Cultures of BAL fluid did not show bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial infections. From these clinical findings and the pathological evidence of granuloma formation, a diagnosis of renal-limited sarcoidosis was made.

After admission, the patient’s renal function continued to deteriorate, and the serum creatinine progressively rose to 2.73 mg/dL within a month (Fig. 1). Because the patient showed no physical signs of infection, including tuberculosis, treatment with prednisolone at 30 mg/day (0.5 mg/kg/day) was started to prevent further deterioration of kidney function. The proteinuria subsequently disappeared and the CRP level normalized. No worsening of the type 2 diabetes was seen. The patient’s acute kidney injury gradually improved, and the serum creatinine decreased to 1.31 mg/dL by August 2014 (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged, and oral prednisolone was gradually tapered on an outpatient basis.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a rare disorder with an estimated prevalence of 10–20 cases per 100,000 population [17]. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder, and most frequently involves the lungs. Although pulmonary involvement is by far the most frequent finding, extrapulmonary disease including the skin, eyes and lymph nodes are also common. According to one case control study of 736 patients with sarcoidosis, 95 % of the patients showed lung involvement as assessed from chest radiography, pulmonary function tests or dyspnea score; 25 % of the patients showed cutaneous involvement; and 12 % of the patients showed ocular involvement [18].

Our patient initially presented with non-specific symptoms and unexplained renal impairment. Reaching the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was challenging, because none of the clinical examinations or imaging tests revealed any evidence of pulmonary sarcoidosis, and no cutaneous or ocular involvement was found in the present case.

GIN is a rare histological diagnosis present in 0.5–0.9 % of native renal biopsies [8]. GIN has been associated with pharmacotherapy, infection, sarcoidosis, crystal deposits, paraproteinemia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and is also seen in an idiopathic form [9]. In the present case, no medications had been added in the 3 years preceding renal function deterioration. In addition to this, absence of peripheral eosinophilia, eosinouria, fever, or drug rash excluded the possibility of medication-related GIN. No physical or laboratory findings suggested infection, paraproteinemia or GPA (Table 1). Costabel et al. showed that a CD4:CD8 ratio >3.5 has a specificity of 94 %, and Winterbauer et al. described a CD4:CD8 ratio >4.0 as offering 96 % specificity for a diagnosis of sarcoidosis [19, 20]. Thus, increased uptake in kidney on 67Ga scintigraphy, an elevated CD4:CD8 ratio of 6.4, tuberculin skin test negativity in spite of having a well-documented positive result before admission, and a markedly elevated serum lysozyme level coupled with the exclusion of other possible secondary causes of GIN established a clinicopathological diagnosis of renal sarcoidosis, which induced acute kidney injury without hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria [21, 22].

GIN is rarely diagnosed, since this pathology is usually clinically silent and does not affect renal function [5]. To date, approximately 80 cases of sarcoid GIN with abnormal renal function have been reported [5–16]. It is important to note that most of those patients showed evidence of extrarenal sarcoid manifestations, and that kidney failure caused by GIN in the absence of extrarenal sarcoidosis is extremely rare. To our knowledge, approximately 20 cases of GIN without extrarenal sarcoid manifestations have been reported [8, 9, 12–14, 16]. Among these, clinical findings supporting a diagnosis of sarcoidosis were evident in only seven cases (Table 2). In our case, although the elevated CD4:CD8 ratio implied the possibility that pulmonary manifestations would develop in the future, according to the definition of organ involvement proposed by the ACCESS study [23], thoracic involvement was excluded by the absence of abnormal findings from chest X-ray, CT and pulmonary function testing. Likewise, no extrarenal organ manifestations including skin, eyes, liver, heart, and nervous system were found according to the definition. Therefore, the present case is the eighth reported case of renal failure caused by renal-limited sarcoidosis with pathological evidence of GIN (Table 2). From the point of view of causes of renal failure, four of the seven cases described above showed hypercalcemia, which made it difficult to conclude whether the renal dysfunction was caused by hypercalcemia or by GIN. From that perspective, the present report is the fourth case of renal failure caused only by sarcoid GIN without extrarenal manifestations. Moreover, in these four cases, the present report is the first to document acute kidney injury caused by isolated sarcoid GIN without serum ACE elevation.

Table 2.

Published cases and the present case of isolated renal sarcoidosis treated with steroids

| References | Year | Age (years) | Sex | ACE | Serum calcium (mmol/L) | Proteinuria | ECC at diagnosis (mL/min) | Initial PSL dose (mg/day) | Best ECC (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | 2001 | NR | NR | Elevated | Normal | Present | NR | NR | NR |

| [12] | 2003 | 70 | M | Elevated | 3.47 | Present | 10 | 30 | 20 |

| 69 | M | Elevated | 2.63 | Present | 16 | 40 | 29 | ||

| 72 | M | Elevated | Normal | Not present | 29 | 20 | 44 | ||

| [9] | 2007 | 67 | M | Elevated | 3.24 | NR | 26 | NR | 78 |

| 63 | M | Elevated | Normal | NR | 4 | NR | 29 | ||

| [16] | 2014 | 69 | M | Normal | 2.65 | Not present | 8 | 60 | Dialysis |

| Present case | 2014 | 76 | M | Normal | Normal | Present | 26 | 30 | 47 |

NR not reported, M male, F female, ACE serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, ECC estimated creatinine clearance, PSL prednisolone

Among patients with reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), corticosteroid therapy is the treatment of choice for sarcoid-related GIN, often resulting in significant improvement in kidney function [24]. Although the present patient was known to have type 2 diabetes, and long-term steroid use carries a risk of worsening diabetes, initiating corticosteroid therapy for subacute kidney injury seemed inevitable. To date, the optimal dose of prednisolone to treat sarcoid-related GIN remains unclear. Referring to a report of 17 patients with advanced tubulointerstitial nephritis due to sarcoidosis [24], a prednisolone dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight was selected, resulting in significant improvement in renal function. In one of the largest series of sarcoid tubulointerstitial nephritis, with 17 cases, the median rate of improvement in estimated creatinine clearance (ECC) was approximately +23 mL/min/year in the first year after starting steroid therapy [24]. In our case, ECC decreased to 23 mL/min by 1 month after admission, and improved to 47 mL/min by 3 months after starting steroid therapy. ECC in our patient thus increased by 24 mL/min in 3 months, better than the rate of improvement reported in the above series. This may be partly attributable to the early initiation of steroid treatment after the onset of sarcoidosis.

In summary, we present an extremely rare case of acute kidney injury caused by sarcoid GIN without extrarenal manifestation, and successfully treated with steroid therapy. This report shows that in cases of AKI with GIN, evaluation of the CD4:CD8 ratio can be effective for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, even if pulmonary manifestations are not evident, and highlights the fact that prompt diagnosis of renal sarcoid involvement and early treatment with steroids can lead to recovery of renal function in sarcoid GIN.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.James DG. Descriptive definition and historic aspects of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997;18:663–679. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(05)70411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzato G, Palmieri G, Agrati AM, Zanussi C. The organ-specific extrapulmonary presentation of sarcoidosis: a frequent occurrence but a challenge to an early diagnosis. A 3-year-long prospective observational study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacSearraigh ET, Doyle CT, Twomey M, O’Sullivan DJ. Sarcoidosis with renal involvement. Postgrad Med J. 1978;54:528–532. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.54.634.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergner R, Hoffmann M, Waldherr R, Uppenkamp M. Frequency of kidney disease in chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casella FJ, Allon M. The kidney in sarcoidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1555–1562. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V391555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannedouche T, Grateau G, Noël LH, Godin M, Fillastre JP, Grünfeld JP, Jungers P. Renal granulomatous sarcoidosis: report of six cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:18–24. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guenel J, Chevet D. Interstitial nephropathies in sarcoidosis. Effect of corticosteroid therapy and long-term evolution. Retrospective study of 22 cases. Nephrologie. 1988;9:253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Riordan E, Willert RP, Reeve R, Kalra PA, O’Donoghue DJ, Foley RN, Waldek S. Isolated sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis: review of five cases at one center. Clin Nephrol. 2001;55:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:222–230. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01790506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal V, Crisi GM, D’Agati VD, Freda BJ. Renal sarcoidosis presenting as acute kidney injury with granulomatous interstitial nephritis and vasculitis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:303–308. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruzado JM, Poveda R, Mañá J, Carreras L, Carrera M, Grinyó JM, Alsina J. Interstitial nephritis in sarcoidosis: simultaneous multiorgan involvement. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:947–951. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson MG, Banerjee D, Hopster D, Cairns HS. Seven cases of granulomatous interstitial nephritis in the absence of extrarenal sarcoid. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:280–284. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed MM, Mubashir E, Dossabhoy NR. Isolated renal sarcoidosis: a rare presentation of a rare disease treated with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1346–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyoshi K, Okura T, Manabe S, Watanabe S, Fukuoka T, Higaki J. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis due to isolated renal sarcoidosis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2004;8:279–282. doi: 10.1007/s10157-004-0294-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda S, Hoshino T, Nakamura T. A case of sarcoidosis with severe acute renal failure requiring dialysis. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:273–277. doi: 10.5414/CN107717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghafoor A, Almakki A. Renal confined sarcoidosis: natural history and diagnostic challenge. Avicenna J Med. 2014;4:44–47. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.130346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas KW, Hunninghake GW. Sarcoidosis. JAMA. 2003;289:3300–3303. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winterbauer RH, Lammert J, Selland M, Wu R, Corley D, Springmeyer SC. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell populations in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Chest. 1993;104:352–361. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costabel U, Hunninghake GW. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:735–737. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d02.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoyle C, Dawson J, Mather G. Skin sensitivity in sarcoidosis. Lancet. 1954;267:164–168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(54)90139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studdy PR, Bird R, Neville E, James DG. Biochemical findings in sarcoidosis. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33:528–533. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.6.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Yeager H., Jr Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajakariar R, Sharples EJ, Raftery MJ, Sheaff M, Yaqoob MM. Sarcoid tubulo-interstitial nephritis: long-term outcome and response to corticosteroid therapy. Kidney Int. 2006;70:165–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]