Abstract

Treatment of acute pancreatitis (AP) is one of the critical challenges to the field of gastroenterology because of its high mortality rate and high medical costs associated with the treatment of severe cases. Early-phase treatments for AP have been optimized in Japan, and clinical guidelines have been provided. However, changes in early-phase treatments and the relationship between treatment strategy and clinical outcome remain unclear. Retrospective analysis of nationwide epidemiological data shows that time for AP diagnosis has shortened, and the amount of initial fluid resuscitation has increased over time, indicating the compliance with guidelines. In contrast, prophylactic use of broad-spectrum antibiotics has emerged. Despite the potential benefits of early enteral nutrition, its use is still limited. The roles of continuous regional arterial infusion in the improvement of prognosis and the prevention of late complications are uncertain. Furthermore, early-phase treatments have had little impact on late-phase complications, such as walled-off necrosis, surgery requirements and late (> 4 w) AP-related death. Based on these observations, early-phase treatments for AP in Japan have approached the optimal level, but late-phase complications have become concerning issues. Early-phase treatments and the therapeutic strategy for late-phase complications both need to be optimized based on firm clinical evidence and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: Diagnostic time, Fluid resuscitation, Enteral nutrition, Continuous regional arterial infusion, Walled-off necrosis

Core tip: We analyzed past nationwide epidemiological survey data for acute pancreatitis (AP) to assess the trend in early-phase treatments and late complications. Early-phase treatments for AP in Japan have improved in line with clinical guidelines, but several points still need attention. In addition, early-phase treatments have had little impact on late complications and clinical outcomes, suggesting that an optimized strategy for late complications is still needed.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is one of the primary reasons for hospitalization in the field of gastroenterology[1], and a substantial number of AP cases progress to severe AP, which is accompanied by organ failure[2]. This condition can be fatal, and therefore multiple severity assessment strategies have been developed worldwide, including in Japan[3]. To assess the detailed clinical features of AP in Japanese patients, nationwide epidemiological surveys have been conducted[4-6]. These surveys consisted of a first survey that involved estimating the number of AP patients by stratified random sampling and a second survey that involved the collection of detailed clinical characteristics regarding patients with AP. According to the latest epidemiological survey for AP in Japan, the number of patients with AP is still increasing; there were over 60000 patients in 2011[4]. Based on previous studies, incident of AP varies among countries[7,8]. The overall mortality rate of AP has lowered to 2.6%, but in case of severe AP, the mortality rate remains at 10.1%, according to the 2011 survey[4]. Since around 1500 AP-related deaths are expected annually in Japan, clinical factors and early-phase treatments associated with AP outcome need to be identified.

Recent reports suggest that a patient’s condition on admission or during the early-phase can predict AP severity, such as organ failure. For example, elevated serum triglycerides within 72 h of presentation are independently associated with organ failure[9]. This correlation was also confirmed in the 2011 survey data[10]. Similarly, patients with AP and disseminated intravascular coagulation or elevated D-dimer on admission were accompanied with a higher organ failure ratio and mortality rate[11,12]. We previously assessed the past nationwide survey data to identify any trends in the management of AP, and confirmed that the treatment strategy for late complications has shifted to less-invasive, step-up approaches in the last decade[13]. However, clinical factors that determine late-phase complications have not yet been identified. Benefits of early-phase treatments in the prevention of late-phase complications also need to be ascertained. In addition, changes in early-phase AP treatments in the last decade might elucidate potential clinical problems that need to be solved. To address this issue, we performed retrospective analysis of the results to nationwide epidemiological surveys. These surveys were conducted mainly by the Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases, under the support of the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan in 2003, 2007, and 2011[4-6]. In this editorial, we review anonymous data of the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of AP, as collected by postal surveys. Clinical data of 2694 patients in the 2011 survey, 2256 patients in the 2007 survey, and 1779 patients in the 2003 survey were assessed[4-6]. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (article#: 2015-1-519).

IMPROVEMENT OF REQUIRED TIME FOR AP DIAGNOSIS

In 2003 survey, 84.0% of total AP cases were diagnosed within 48 h. This ratio significantly increased with time, reaching 91.5% in the 2011 survey (Table 1). The ratio of patients diagnosed later than 72 h was 9.1% in the 2003 survey, which decreased to 4.8% in the 2011 survey. This trend was similar in patients with severe AP; 93.6% of severe AP cases were diagnosed within 48 h in the 2011 survey, compared to 84.9% in the 2003 survey (Table 1). These results suggest that the required time for AP diagnosis in Japan has improved in the last decade. Current Japanese guidelines for the management of AP recommend serum lipase or amylase measurements and imaging studies [computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] for the diagnosis of AP[14], as well as severity assessment using the revised severity scoring system of AP (2008)[15,16]. Immediate transfer of patients with severe AP to an adequate facility capable of providing suitable treatment is also recommended[14]. Awareness of these principles in Japan might be the reason for the improved diagnosis time of AP.

Table 1.

Required time for acute pancreatitis diagnosis n (%)

| 2003 Survey | 2007 Survey | 2011 Survey | P value | |

| Time for diagnosis | ||||

| (Total AP) | ||||

| ≤ 12 h | 707 (51.6) | 806 (58.8) | 1148 (61.7) | < 0.00011 |

| 13-24 h | 288 (21.0) | 252 (18.4) | 359 (19.3) | |

| 25-48 h | 156 (11.4) | 150 (10.9) | 195 (10.5) | |

| 49-72 h | 95 (6.9) | 70 (5.1) | 69 (3.7) | |

| ≥ 73 h | 124 (9.1) | 94 (6.8) | 89 (4.8) | |

| Time for diagnosis (Severe AP) | ||||

| ≤ 12 h | 148 (53.1) | 170 (60.9) | 240 (66.8) | 0.0031 |

| 13-24 h | 54 (19.3) | 51 (18.3) | 71 (19.8) | |

| 25-48 h | 35 (12.5) | 31 (11.1) | 25 (7.0) | |

| 49-72 h | 20 (7.2) | 15 (5.4) | 13 (3.6) | |

| ≥ 73 h | 22 (7.9) | 12 (4.3) | 10 (2.8) |

χ2 test. AP: Acute pancreatitis.

INCREASED AMOUNT OF INITIAL FLUID RESUSCITATION VOLUME

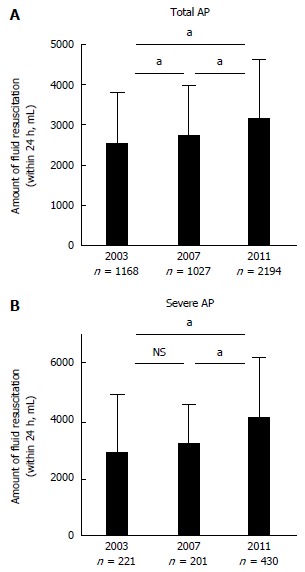

Fluid resuscitation is an essential initial therapy for AP. The Japanese guidelines recommend extracellular solution, such as Ringer’s Lactate solution[14]. Even though there was no benefit in use of Ringer’s Lactate over normal saline in one study[17], further validation is necessary to establish the best fluid resuscitation strategy. A previous report pointed out that the amount of fluid volume administered in 48 h to patients with AP admitted into intensive care units (ICU) was significantly less in non-survivors than in survivors[18]. A faster ratio of fluid resuscitation lowered the mortality rate of AP patients, according to another report[19]. Average fluid resuscitation for all AP patients within 24 h after admission was 2538.5 ± 1256.1 mL in 2003, 2725.4 ± 1232.1 mL in 2007, and 3145.1 ± 1475.2 mL in 2011, respectively (Figure 1A). Average fluid resuscitation for patients with severe AP within 24 h after admission was 2885.2 ± 1989.1 mL in 2003, 3175.6 ± 1391.0 mL in 2007 and 4103.7 ± 2063.3 mL in 2011, respectively (Figure 1B). Current Japanese guidelines for the management of AP describe the detailed fluid resuscitation strategy as an initial therapy[14], and this therapeutic concept has been widely accepted in Japan.

Figure 1.

Average amount of fluid resuscitation. A: Average amount of fluid resuscitation within 24 h after admission for total acute pancreatitis (AP) patients. Error bar shows standard deviation. aP < 0.01; B: Average amount of fluid resuscitation within 24 h after admission for severe AP patients. Error bar shows standard deviation. aP < 0.01.

TREND IN PROPHYLACTIC ADMINISTRATION OF ANTIBIOTICS

Usage of prophylactic antibiotics for AP treatment is still a matter of debate. Japanese guidelines for the management of AP state that prophylactic administration may improve the prognosis of severe or necrotizing pancreatitis[14], but another report indicated that prophylactic administration does not affect mortality[20]. Current retrospective analysis identified increasing use of carbapenem for AP treatment in the last decade, especially in the case of severe AP (Table 2). Carbapenem-resistant bacteria are a serious danger to health, and this resistance is partly promoted by a patient’s prior use of carbapenem[21]. This fact highlights that the strategy for the use of antibiotics in Japan still needs to be optimized. Continuous administration of antibiotics for more than 2 wk is not recommended in patients without signs of infection, according to Japanese guidelines[14]. Similarly, prophylactic administration for mild pancreatitis is stated as unnecessary, and these guidelines should be followed.

Table 2.

Prophylactic administration of antibiotics within 24 h n (%)

| 2003 survey | 2007 survey | 2011 survey | P value | |

| Antibiotics (Total AP) | ||||

| Carbapenem | 280 (27.7) | 327 (32.5) | 689 (36.9) | < 0.00011 |

| Cephem | 270 (26.7) | 264 (26.2) | 485 (26.0) | |

| Cephem/β-lactamase inhibitor combination | 429 (42.4) | 390 (38.8) | 641 (34.4) | |

| Others | 33 (3.2) | 25 (2.5) | 51 (2.7) | |

| Antibiotics (Severe AP) | ||||

| Carbapenem | 86 (41.2) | 107 (52.2) | 286 (67.3) | < 0.00011 |

| Cephem | 54 (25.8) | 36 (17.6) | 48 (11.3) | |

| Cephem/β-lactamase inhibitor combination | 62 (29.7) | 57 (27.8) | 80 (18.8) | |

| Others | 7 (3.3) | 5 (2.4) | 11 (2.6) |

χ2 test. AP: Acute pancreatitis.

INCREASED USAGE OF ENTERAL NUTRITION IN SEVERE AP

Usage of enteral nutrition for treatment of severe AP in the 2011 survey was significantly increased, compared with the 2007 survey (Table 3). Patients with severe AP treated in hospitals with 500 beds or more were treated with enteral nutrition more frequently than patients treated in hospitals with less than 500 beds (Table 3). Since enteral nutrition is associated with fewer infection-related complications and with length of hospital stay[22], its efficacy needs to be more widely recognized and a detailed procedure for its routine use needs to be produced. The optimal time to start enteral nutrition is within 48 h of admission, according to the Japanese guidelines[14]. This recommendation is based on the result of a meta-analysis that identified the superiority of early (within 48 h) enteral nutrition over late enteral nutrition or total parenteral nutrition[23]. In patients with severe AP not having severe ileal or intestinal ischemia, addition of enteral nutrition should be considered as an initial therapy.

Table 3.

Enteral nutrition n (%)

| Enteral nutrition (Total AP) | 2007 survey | 2011 survey | P value |

| Yes | 72 (4.7) | 135 (6.2) | 0.051 |

| No | 1466 (95.3) | 2053 (93.8) | |

| Enteral nutrition (Severe AP) | 2007 survey | 2011 survey | P value |

| Yes | 45 (14.6) | 97 (22.4) | 0.0081 |

| No | 264 (85.4) | 337 (77.6) | |

| Enteral nutrition (Severe AP in 2011 survey) | < 500 beds | 500 beds or more | P value |

| Yes | 14 (9.9) | 83 (28.4) | < 0.00011 |

| No | 127 (90.1) | 209 (71.6) |

χ2 test. AP: Acute pancreatitis.

TREND IN CONTINUOUS REGIONAL ARTERIAL INFUSION AND MORTALITY

Continuous regional arterial infusion (CRAI) has developed for the improvement of regional inflammation and infection in the pancreas, by trans-arterial administration of antibiotics and protease inhibitor. Its therapeutic efficacy in Japan has been reported [24]. Previous study reported an effectiveness of CRAI in randomized controlled study[25]. CRAI was performed in 18.0% of all AP patients and 22.4% of severe AP patients in the 2003 survey (Table 4). This ratio significantly decreased in the later surveys, with 4.5 and 4.3% for all AP patients, and 14.6 and 17.2% for severe AP patients, in 2007 and 2011 respectively (Table 4). The decrease in the CRAI ratio during this decade might have been due to the discretion, excluding patients without less-enhanced region in the pancreas based on the contrast-enhanced CT findings. CRAI might have been limited to patients with severe AP accompanied with lesions that were less enhanced in the CT scan or with necrosis in the pancreas. The mortality rate of patients with severe AP who received CRAI was also assessed. In the 2003 survey, the mortality of patients who received CRAI was significantly higher than that of patients who did not receive CRAI (Table 5). This difference was not significant in the 2007 and 2011 surveys. A recent retrospective multicenter study also reported that CRAI has no efficacy in the treatment of severe AP[26], which is in agreement with the current observation. These results indicate that further assessment of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of CRAI is needed before the standard therapeutic strategy is defined.

Table 4.

Trend in continuous regional arterial infusion n (%)

| 2003 survey | 2007 survey | 2011 survey | P value | |

| CRAI (Total AP) | ||||

| Yes | 118 (18.0) | 72 (4.5) | 95 (4.3) | < 0.00011 |

| No | 538 (82.0) | 1530 (95.5) | 2129 (95.7) | |

| CRAI (Severe AP) | ||||

| Yes | 72 (22.4) | 51 (14.6) | 76 (17.2) | 0.0271 |

| No | 249 (77.6) | 299 (85.4) | 365 (82.8) | |

χ2 test. CRAI: Continuous regional arterial infusion; AP: Acute pancreatitis.

Table 5.

Continuous regional arterial infusion and mortality

| CRAI | 2003 survey | 2007 survey | 2011 survey |

| (Severe AP) | Mortality | Mortality | Mortality |

| Yes | 15/71 (21.1) | 5/49 (10.2) | 7/74 (9.5) |

| No | 23/238 (9.7) | 27/279 (9.7) | 35/327 (10.7) |

| P value | 0.00981 | 0.909 | 0.752 |

χ2 test. CRAI: Continuous regional arterial infusion; AP: Acute pancreatitis.

FACTORS AFFECTING WALLED-OFF NECROSIS DEVELOPMENT, A PATIENT’S NEED FOR SURGERY, AND LATE (> 4 W) AP-RELATED DEATH IN SEVERE AP

To identify the specific effects of early-phase treatments on severe AP-related complications and clinical outcomes, factors were assessed that affected walled-off necrosis (WON) development, a patient’s need for surgery, and late phase (later than 4 w after onset of AP) AP-related death, in the 2011 survey. Diagnosis within 48 h, average amount of fluid resuscitation, and CRAI did not affect WON development (Table 6). Enteral nutrition was more frequently performed in patients who developed WON. Patients with severe AP who underwent surgery had been provided significantly more fluid resuscitation and enteral nutrition, while CRAI failed to show any preventive effect (Table 7). Late AP-related death was less prevalent in patients diagnosed within 48 h, but the amount of fluid resuscitation, enteral nutrition, and CRAI had little effects (Table 8). These results might be confounded by illness severity, since special therapies such as CRAI or enteral nutrition were possibly performed for the more severe cases. The efficacy of these treatments for the prevention of late complications needs to be assessed by prospective studies observing patients matched for severity. On the other hand, late complications might not be related to the early-phase treatment for AP. If this is correct, the refinement of current therapeutic strategies, such as step-up approaches for WON[27,28] and less-invasive endoscopic necrosectomy[29], will be the best way to improve the prognosis of severe AP.

Table 6.

Factors affecting walled-off necrosis development in severe acute pancreatitis in 2011 survey

| WON (+) | WON (-) | P value | |

| Diagnosis within 48 h | 14/17 (82.4) | 60/63 (95.2) | 0.074 |

| Average amount of fluid resuscitation (mL) | 4865.8 ± 2130.2 | 4661.1 ± 2758.3 | 0.765 |

| Enteral nutrition | 14/22 (63.6) | 24/72 (33.3) | 0.0111 |

| CRAI | 11/23 (47.8) | 21/75 (28.0) | 0.076 |

χ2 test. CRAI: Continuous regional arterial infusion; WON: Walled-off necrosis.

Table 7.

Factors affecting surgery requirement in severe acute pancreatitis in 2011 survey

| Surgery (+) | Surgery (-) | P value | |

| Diagnosis within 48 h | 16/18 (88.9) | 279/300 (94.6) | 0.513 |

| Average amount of fluid resuscitation (mL) | 6183.6 ± 4109.5 | 4203.1 ± 2810.6 | 0.0031 |

| Enteral nutrition | 13/25 (52.0) | 76/350 (21.7) | 0.00062 |

| CRAI | 8/25 (32.0) | 62/360 (17.2) | 0.064 |

t-test;

χ2 test. CRAI: Continuous regional arterial infusion.

Table 8.

Factors affecting late (> 4W) acute pancreatitis -related death in severe acute pancreatitis in 2011 survey

| AP-related death (> 4W) | Alive | P value | |

| Diagnosis within 48 h | 5/8 (62.5) | 286/305 (98.3) | 0.0131 |

| Average amount of fluid resuscitation (mL) | 5525.0 ± 3415.5 | 4295.5 ± 2914.7 | 0.154 |

| Enteral nutrition | 6/12 (50.0) | 85/354 (24.0) | 0.081 |

| CRAI | 0/12 (0.0) | 76/355 (21.4) | 0.138 |

Fisher’s exact test. CRAI: Continuous regional arterial infusion.

CONCLUSION

Current retrospective analysis identified an improvement over the last decade in the length of time it takes to receive a diagnosis of AP and in the performance of fluid resuscitation. These results indicate good recognition of the guidelines for the management of AP. However, prophylactic administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics for AP has been widespread in Japan, and this needs to be reversed. Use of enteral nutrition is still limited, and needs to be practiced more routinely. The efficacy of CRAI has been a matter of debate in the last decade, and the current study did not reveal any clear efficacy of CRAI in AP treatment. This result is in agreement with a recent study[22]. In addition, early-phase treatments have little impact on late complications, such as WON, a patient’s need for surgery, and late AP-related death. The efficacy of special treatments such as CRAI and enteral nutrition for the prevention of late complications needs further validation, but if these are not especially effective, refinement of therapeutic approaches will be necessary for the improvement of prognosis. In conclusion, both early-phase treatments and late-phase interventions for AP need to be optimized based on firm evidence and cost-effectiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs. Makoto Otsuki and Yasuyuki Kihara for the 2003 nationwide survey. The authors are grateful to Dr. Kazuhiro Kikuta for the great help preparing 2011 survey.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review started: January 27, 2017

First decision: February 23, 2017

Article in press: March 21, 2017

P- Reviewer: Luchini C S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1972–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1505202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mounzer R, Langmead CJ, Wu BU, Evans AC, Bishehsari F, Muddana V, Singh VK, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Yadav D, et al. Comparison of existing clinical scoring systems to predict persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1476–182; quiz 1476-182;. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Tsuji I, Shimosegawa T. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2014;43:1244–1248. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh K, Shimosegawa T, Masamune A, Hirota M, Kikuta K, Kihara Y, Kuriyama S, Tsuji I, Satoh A, Hamada S. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2011;40:503–507. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318214812b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otsuki M, Hirota M, Arata S, Koizumi M, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Takeda K, Mayumi T, Kitagawa M, Ito T, et al. Consensus of primary care in acute pancreatitis in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3314–3323. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i21.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNabb-Baltar J, Ravi P, Isabwe GA, Suleiman SL, Yaghoobi M, Trinh QD, Banks PA. A population-based assessment of the burden of acute pancreatitis in the United States. Pancreas. 2014;43:687–691. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spanier B, Bruno MJ, Dijkgraaf MG. Incidence and mortality of acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands: a nationwide record-linked cohort study for the years 1995-2005. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3018–3026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nawaz H, Koutroumpakis E, Easler J, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Singh VP, Yadav D, Papachristou GI. Elevated serum triglycerides are independently associated with persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1497–1503. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. Clinical Impact of Elevated Serum Triglycerides in Acute Pancreatitis: Validation from the Nationwide Epidemiological Survey in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:575–576. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation on Admission Predicts Complications and Poor Prognosis of Acute Pancreatitis: Analysis of the Nationwide Epidemiological Survey in Japan. Pancreas. 2017;46:e15–e16. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomercic C, Gelsi E, Van Gysel D, Frin AC, Ouvrier D, Tonohouan M, Antunes O, Lombardi L, De Galleani L, Vanbiervliet G, et al. Assessment of D-Dimers for the Early Prediction of Complications in Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2016;45:980–985. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada S, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T. Management of acute pancreatitis in Japan: Analysis of nationwide epidemiological survey. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6335–6344. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoe M, Takada T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Isaji S, Wada K, Itoi T, Sata N, Gabata T, Igarashi H, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: Japanese Guidelines 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:405–432. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Yasuda T, Kamei K, Satoi S, Sawa H, Shinzeki M, Ku Y, Kuroda Y, Ohyanagi H. Utility of the new Japanese severity score and indications for special therapies in acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otsuki M, Takeda K, Matsuno S, Kihara Y, Koizumi M, Hirota M, Ito T, Kataoka K, Kitagawa M, Inui K, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis and severity stratification of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5798–5805. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipinski M, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Rydzewski A, Rydzewska G. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: Normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9367–9372. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mole DJ, Hall A, McKeown D, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Detailed fluid resuscitation profiles in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner TB, Vege SS, Chari ST, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Levy MJ, Sarr MG. Faster rate of initial fluid resuscitation in severe acute pancreatitis diminishes in-hospital mortality. Pancreatology. 2009;9:770–776. doi: 10.1159/000210022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ignatavicius P, Vitkauskiene A, Pundzius J, Dambrauskas Z, Barauskas G. Effects of prophylactic antibiotics in acute pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Righi E, Peri AM, Harris PN, Wailan AM, Liborio M, Lane SW, Paterson DL. Global prevalence of carbapenem resistance in neutropenic patients and association with mortality and carbapenem use: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw459. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Meta-analysis of parenteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2004;328:1407. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38118.593900.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li JY, Yu T, Chen GC, Yuan YH, Zhong W, Zhao LN, Chen QK. Enteral nutrition within 48 hours of admission improves clinical outcomes of acute pancreatitis by reducing complications: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imaizumi H, Kida M, Nishimaki H, Okuno J, Kataoka Y, Kida Y, Soma K, Saigenji K. Efficacy of continuous regional arterial infusion of a protease inhibitor and antibiotic for severe acute pancreatitis in patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Pancreas. 2004;28:369–373. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piaścik M, Rydzewska G, Milewski J, Olszewski S, Furmanek M, Walecki J, Gabryelewicz A. The results of severe acute pancreatitis treatment with continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitor and antibiotic: a randomized controlled study. Pancreas. 2010;39:863–867. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181d37239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horibe M, Sasaki M, Sanui M, Sugiyama D, Iwasaki E, Yamagishi Y, Sawano H, Goto T, Ikeura T, Hamada T, et al. Continuous Regional Arterial Infusion of Protease Inhibitors Has No Efficacy in the Treatment of Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Pancreas. 2017;46:510–517. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Grinsven J, van Brunschot S, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, Boermeester MA, Bruno MJ, Dejong CH, Dijkgraaf MG, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, et al. Diagnostic strategy and timing of intervention in infected necrotizing pancreatitis: an international expert survey and case vignette study. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Iwai T, Isayama H, Itoi T, Hisai H, Inoue H, Kato H, Kanno A, Kubota K, et al. Japanese multicenter experience of endoscopic necrosectomy for infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis: The JENIPaN study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:627–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]