Abstract

Summary

Background

The mixed μ‐ and κ‐opioid receptor agonist and δ‐opioid receptor antagonist, eluxadoline, is licensed in the USA for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea (IBS‐D), based on the results of two large Phase 3 clinical trials.

Aim

To understand the time course of treatment benefits with eluxadoline by comparing responder rates over the first month of treatment with responder rates over longer treatment intervals.

Methods

In this post hoc analysis of two Phase 3 studies, composite and adequate relief (AR) responder rates were calculated over month 1 and patients were stratified by their responder status. Cumulative counts over subsequent intervals (months 1–3, months 1–6, months 2 through 6) were tallied.

Results

The studies randomised 2428 patients. Over month 1, 24.6%, 22.8% and 12.5% of patients were composite responders with eluxadoline 100 mg, eluxadoline 75 mg and placebo respectively. For month 1 responders, 77.8% and 81.5% (over months 1–3) and 70.7% and 73.9% (over months 1–6) showed a continuous response with eluxadoline 100 mg and 75 mg respectively. [Correction added on 5 April 2017, after first online publication: The percentage for the responders over months 1–3 was previously wrong and has been corrected.] Of the month 1 nonresponders, <20% showed a response over months 1–3 or months 1–6. Similar results were seen for the analysis of proportions of AR responders over these time intervals.

Conclusions

Over two‐thirds of patients who respond over the first month retain a positive response over 6 months of treatment with eluxadoline, indicating that early clinical response to eluxadoline is associated with sustained benefits for up to 6 months in patients with IBS‐D.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that is characterised by recurring abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habits in the absence of demonstrable organic disease.1, 2 IBS is diagnosed using the Rome III criteria, and can be classified into subtypes according to the predominant stool pattern, including IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhoea (IBS‐D) and IBS with mixed bowel habits.1 It has been estimated that ~40% of IBS cases fall into the IBS‐D subtype,3 characterised by loose or watery stools for ≥25% and hard or lumpy stools for <25% of bowel movements;1 however, some overlap of symptoms has been reported with functional diarrhoea.4

Irritable bowel syndrome is estimated to affect up to 20% of adults in the US population,5 is one of the most commonly diagnosed GI disorders,6 and is associated with higher levels of somatisation, expressed as the feeling of tiredness and the experience of bloating.7 In the majority of patients, IBS is a chronic, relapsing disease, with a previous systematic review finding that IBS symptoms worsened over the course of long‐term follow‐up for 2–18% of patients, and remained the same for 30–50% of patients.8 As a result of its chronic nature, IBS is associated with a significant economic burden and extensive healthcare resource utilisation,6 as well as a marked impact on patient health‐related quality of life.9, 10

Eluxadoline is a mixed μ‐ and κ‐opioid receptor agonist and δ‐opioid receptor antagonist, approved for the treatment of IBS‐D in adults.11 Opioid receptors in the GI tract are known to modulate gut motility and secretion,12 with pre‐clinical studies showing that eluxadoline normalised disrupted GI transit over a wide dose range in mice.13 Two large Phase 3 studies14 have demonstrated that twice‐daily treatment with eluxadoline is effective vs. placebo in simultaneously relieving the symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhoea associated with IBS‐D, measured using a composite efficacy endpoint combining stool consistency and abdominal pain responses.

Given the chronic nature of IBS‐D, it is important to clearly understand the time course of treatment benefits seen with eluxadoline, and secondary to this, to define the outcomes of patients who show either an initial response or lack of response to eluxadoline treatment. More specifically, will those who respond early continue to respond over time, and will those who fail to respond early on ultimately show a response with continued treatment? These post hoc analyses of the two Phase 3 clinical studies therefore evaluated proportions of composite responders over the first month of treatment, compared with response rates over longer treatment intervals. Continued efficacy with eluxadoline treatment was also evaluated using IBS adequate relief (AR) response rates as an alternative efficacy measure, as the composite response rate may underestimate treatment benefit.

Methods

Study design

Two double‐blind, placebo controlled, Phase 3 clinical trials (IBS‐3001; NCT01553591 and IBS‐3002; NCT01553747) randomised patients 1:1:1 to twice‐daily treatment with eluxadoline 100 or 75 mg or placebo. The methodology and results of these two studies have been described previously.14

Briefly, both studies were identical through 26 weeks of treatment, followed by a 26‐week safety assessment and a 2‐week follow‐up period (IBS‐3001 only) or a 4‐week single‐blind placebo withdrawal period (IBS‐3002 only). Enrolled participants used an electronic diary with an interactive voice response system to record daily IBS‐D symptoms and bowel function, and weekly assessments of AR through week 26.

Wherever possible, all patients withdrawing from the studies prematurely were to undergo all end‐of‐treatment/early withdrawal assessments. Patients who discontinued participation in the studies for any reason following randomisation were not replaced.

Patient population

Patients aged 18–80 meeting the Rome III criteria for IBS‐D1 were enrolled. Eligible patients recorded an average worst abdominal pain score >3.0 (scale of 0–10, with 0 indicating no pain, and 10 the worst imaginable pain), an average score for stool consistency of ≥5.5 on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS; scale of 1–7, with 1 indicating hard stool, and 7 watery diarrhoea), and an average IBS‐D global symptom score of ≥2.0 (scale of 0–4, with 0 indicating no symptoms of IBS‐D and 4 very severe symptoms of IBS‐D) during the week before randomisation.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease or coeliac disease, abnormal thyroid function, history of alcohol abuse15 or binge drinking,16 prior pancreatitis, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, post‐cholecystectomy biliary pain, cholecystitis in the past 6 months, intestinal obstruction, GI infection or diverticulitis in the past 3 months were excluded.

Efficacy endpoints

Details and calculations for the primary endpoint have been described previously.14 As reported by Lembo et al., the primary efficacy endpoint of both studies was a composite response based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a BSFS score of <5 on ≥50% of treatment days.14 AR response was defined by a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’ on ≥50% of weeks. Responder rates for both the composite endpoint and the AR endpoint were determined over the first 3 months of treatment (weeks 1–12) and the first 6 months of treatment (weeks 1–26). Responder rates for the composite endpoint were additionally determined over each individual monthly interval. Monthly interval responder rates for AR were post hoc assessments.

Data analyses

As also reported by Lembo et al., efficacy data were pooled for the two Phase 3 studies, and analyses were performed on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis set, defined as all patients randomised to study treatment.14 No imputation for missing data was performed, as diary compliance rules accounted for absent diary entries. For composite response evaluations, patients were required to have a minimum of 20 diary entries over any monthly interval, 60 days of diary entries over the 3‐month interval and 110 days of diary entries over the 6‐month interval. For AR evaluations, patients had to have ≥6 weekly ‘yes’ responses over the 3‐month interval, and ≥13 weekly ‘yes’ responses over the 6‐month interval; for the post hoc AR assessment, ≥2 weekly ‘yes’ responses over any monthly interval were required. Patients with insufficient diary data for both the composite response and AR response were categorised as nonresponders.

To assess the robustness of an early response signal, responder rates were calculated over the first 4‐week interval (month 1) for both the composite14 and AR (post hoc) outcome variables. Patients were stratified by their status over month 1 (weeks 1–4), and cumulative counts over subsequent intervals were tallied. An additional post hoc evaluation qualitatively assessed the time to onset of treatment benefit by plotting the proportions of patients meeting the AR response criteria for each week over the entire 6 months of diary data collection.

A Bonferroni adjustment was taken only for the primary analyses due to two doses being studied; no further statistical adjustments were made a priori.14 Since these additional analyses were retrospective and the goal of this study was to qualitatively assess treatment benefit over time in order to offer advice to prescribers, no further formal statistical assessments were performed, except for the post hoc adequate relief response over the first month to allow comparison to the previously published composite response rates.

Results

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

A total of 2428 patients were randomised to study treatment (1282 in IBS‐3001; 1146 in IBS‐3002). Patient baseline and demographic characteristics were balanced between the two studies and across treatment groups, as previously described.14 Across both studies, there were more female patients (IBS‐3001: 65.4%; IBS‐3002: 67.0%), and the mean age [standard deviation (s.d.)] was 44.9 (13.7) and 45.9 (13.5) in IBS‐3001 and IBS‐3002 respectively. Patients had a mean (s.d.) weekly average BSFS score at baseline of 6.3 (0.4) and 6.2 (0.4), and a mean (s.d.) weekly average worst abdominal pain score of 6.2 (1.5) and 6.0 (1.5) in IBS‐3001 and IBS‐3002 respectively.

Proportions of responders over time

As previously reported (see figure 2 in Lembo et al.14), a qualitative visual separation of proportions of composite responders with both doses of eluxadoline vs. placebo was observable within the first few days following treatment initiation and reached a peak separation of ~10% within the first 2 weeks of therapy. Once established, the separation in responder proportions between eluxadoline and placebo remained ~10% over the 182 days of diary data collection.

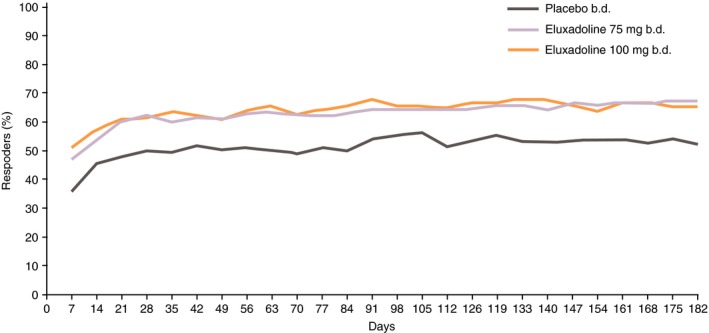

Similarly, by day 7 (the first time point for measurement of AR), separation from placebo occurred and by day 28 (fourth AR measurement), both eluxadoline doses reached response rates of 60%, compared to the AR response rates of 50% seen with placebo (Figure 1). The treatment effect then remained at ~10% over the entire treatment period through 6 months (182 days), and was similar between eluxadoline 100 and 75 mg (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of AR responders over 26 weeks: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. AR response is defined as a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’. AR, adequate relief; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Analysis of early and sustained composite response rates over time

In the pooled Phase 3 population, a significantly greater proportion of patients receiving eluxadoline 100 and 75 mg were composite responders vs. placebo over the 3‐month interval (weeks 1–12) and the 6‐month interval (weeks 1–26).14 Within the pooled ITT analysis set, 765 patients (31.6%) discontinued from the studies over weeks 1–26. Of the subjects in the treatment groups who discontinued, 3–6% were nonresponders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proportions of composite responders among patients completing and discontinuing from the studies over weeks 1–26: pooled Phase 3 studies

| Placebo (n = 809) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n = 808) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n = 806) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients completing | Placebo (n = 563) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n = 539) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n = 556) |

| Responders, n (%) | 150 (26.6) | 208 (38.6) | 235 (42.3) |

| Patients discontinuing | Placebo (n = 246) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n = 269) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n = 250) |

| Responders, n (%) | 8 (3.3) | 8 (3.0) | 15 (6.0) |

A completer is defined as a patient who either had the last day of diary data or last treatment date on or later than day 182, or whose case record form was checked ‘Yes’ on the completion page. A discontinuer is defined as a patient whose case record form was checked ‘No’ on the completion page. Composite response is based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a Bristol Stool Form Scale score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days.

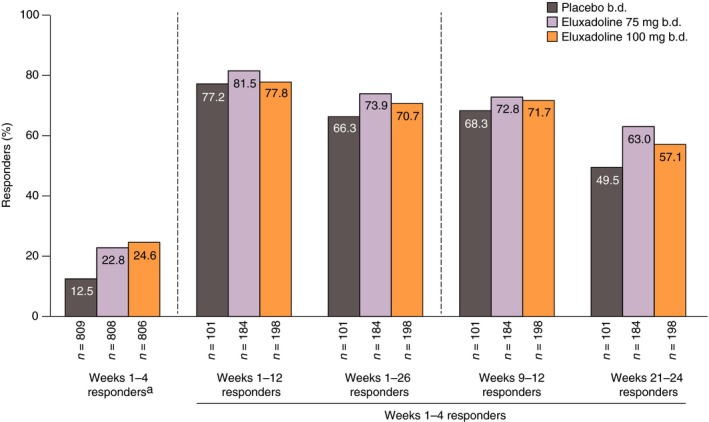

Over month 1 (weeks 1–4), 24.6% of patients receiving eluxadoline 100 mg (P < 0.001 compared with placebo), 22.8% receiving eluxadoline 75 mg (P < 0.001 compared with placebo) and 12.5% receiving placebo were composite responders (see the left panel of Figure 2).14 Among these patients, 77.8% treated with eluxadoline 100 mg were also responders over the 3‐month interval (weeks 1–12), while 81.5% and 77.2% were responders over the 3‐month interval with eluxadoline 75 mg and placebo respectively. Over the longer 6‐month interval (weeks 1–26), 70.7%, 73.9% and 66.3% of month 1 responders with eluxadoline 100 mg, eluxadoline 75 mg and placebo, respectively, had a continuing response. The majority of patients who were composite responders with eluxadoline over month 1 were also responders over the non‐overlapping, distinct intervals of month 3 (weeks 9–12) and month 6 (weeks 21–24), with a similar sustained response observed among the month 1 placebo responders (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Composite responders over weeks 1–4 who remained responders over weeks 1–12, weeks 1–26, weeks 9–12 and weeks 21–24: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. aData shown in Lembo et al.14 Composite response is based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a Bristol Stool Form Scale score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days.

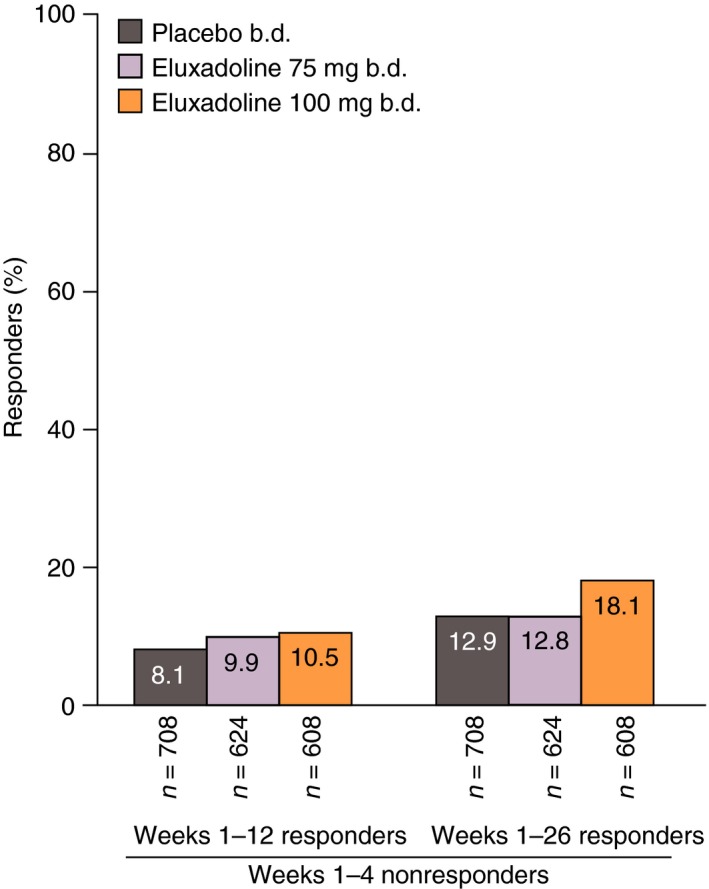

Among patients who were not composite responders over month 1, ~10% in each treatment group became responders over the 3‐month interval (weeks 1–12) (Figure 3). A slightly higher proportion of month 1 nonresponders became responders over the 6‐month interval (weeks 1–26) with eluxadoline 100 mg (18.1%) compared with the other treatment groups (eluxadoline 75 mg: 12.8%; placebo: 12.9%).

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients who were initial nonresponders over weeks 1–4 (month 1) who became composite responders over weeks 1–12 and 1–26: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. Composite response is based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a Bristol Stool Form Scale score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days.

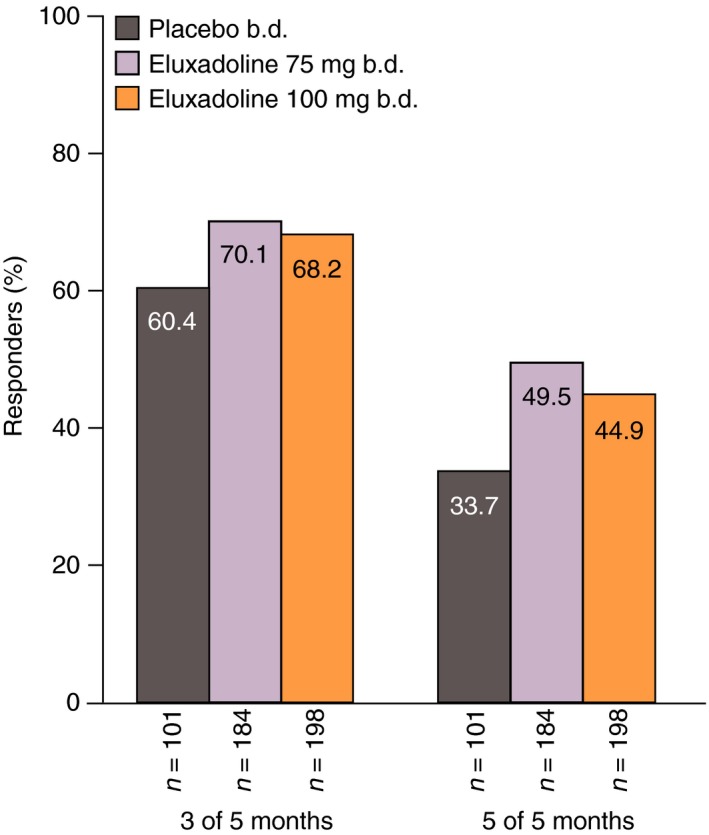

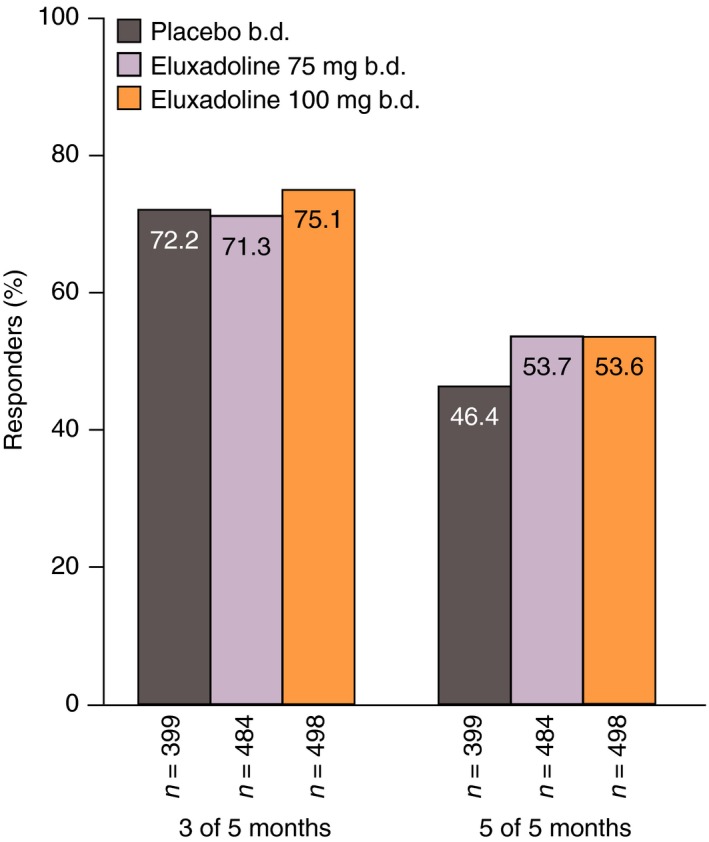

To further evaluate the sustainability of a monthly response, the composite responder status over each subsequent monthly interval (months 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) was determined for the month 1 responders. Of the patients who were composite responders over month 1 (weeks 1–4), 68.2% receiving eluxadoline 100 mg, 70.1% receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and 60.4% receiving placebo showed a sustained response over ≥3 out of any of the five subsequent monthly intervals (Figure 4). Furthermore, nearly half of the month 1 responders treated with eluxadoline 100 mg (44.9%) or eluxadoline 75 mg (49.5%) were responders for all five of the subsequent months of treatment, with around a third of month 1 placebo responders showing a response over all five subsequent months.

Figure 4.

Proportions of composite responders over weeks 1–4 (month 1) who remained responders over 3 or 5 out of the subsequent 5 months: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. Composite response is based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a Bristol Stool Form Scale score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days.

Analysis of early and sustained AR responder rates over time

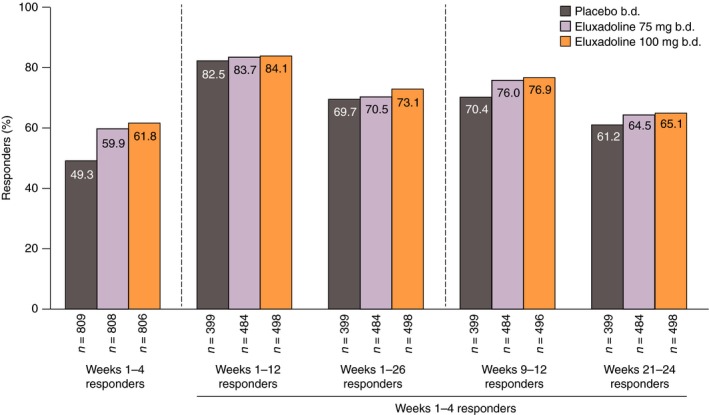

Over month 1 (weeks 1–4), 61.8% of patients receiving eluxadoline 100 mg (P < 0.0001 compared with placebo), 59.9% of patients receiving eluxadoline 75 mg (P < 0.0001 compared with placebo) and 49.3% of patients receiving placebo were AR responders (Figure 5). Of these patients, 84.1% receiving eluxadoline 100 mg had a continuing response over the 3‐month interval (weeks 1–12), while 83.7% and 82.5% of patients receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and placebo, respectively, were 3‐month responders. Over the longer 6‐month interval (weeks 1–26), 73.1%, 70.5% and 69.7% of month 1 AR responders with eluxadoline 100 mg, eluxadoline 75 mg and placebo, respectively, had a continuing response. The majority of patients who were AR responders with eluxadoline over month 1 were also responders over the non‐overlapping intervals of month 3 (weeks 9–12) and month 6 (weeks 21–24) (Figure 5), with similar findings observed for patients who were month 1 placebo responders.

Figure 5.

AR responders over weeks 1–4 who remained responders over weeks 1–12, weeks 1–26, weeks 9–12 and weeks 21–24: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. AR response is defined as a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’ AR, adequate relief; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

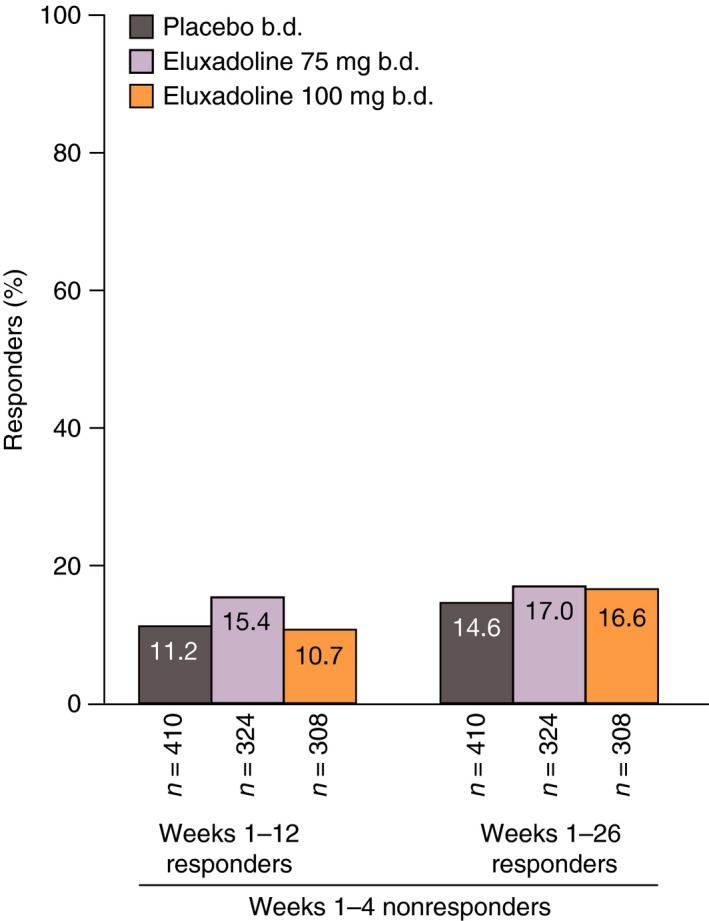

Among patients who were not AR responders over month 1 (weeks 1–4), 10.7% receiving eluxadoline 100 mg, 15.4% receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and 11.2% receiving placebo showed a subsequent AR response over the 3‐month interval (weeks 1–12), and 16.6% receiving eluxadoline 100 mg, 17.0% receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and 14.6% receiving placebo showed a subsequent response over the 6‐month interval (weeks 1–26) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proportions of patients who were initial AR nonresponders over weeks 1–4 (month 1) who became AR responders over weeks 1–12 and 1–26: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. AR response is defined as a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’. AR, adequate relief; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Of the patients who showed an AR response over month 1 (weeks 1–4), a continued response was seen for ≥3 out of any of the five subsequent months for 75.1% receiving eluxadoline 100 mg, 71.3% receiving eluxadoline 75 mg and 72.2% receiving placebo (Figure 7). Proportions of initial responders showing sustained AR responses over all five subsequent months were ~50% for all treatment groups.

Figure 7.

Proportions of AR responders over weeks 1–4 (month 1) who remained responders over 3 or 5 out of the subsequent 5 months: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. AR response is defined as a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’. AR, adequate relief; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

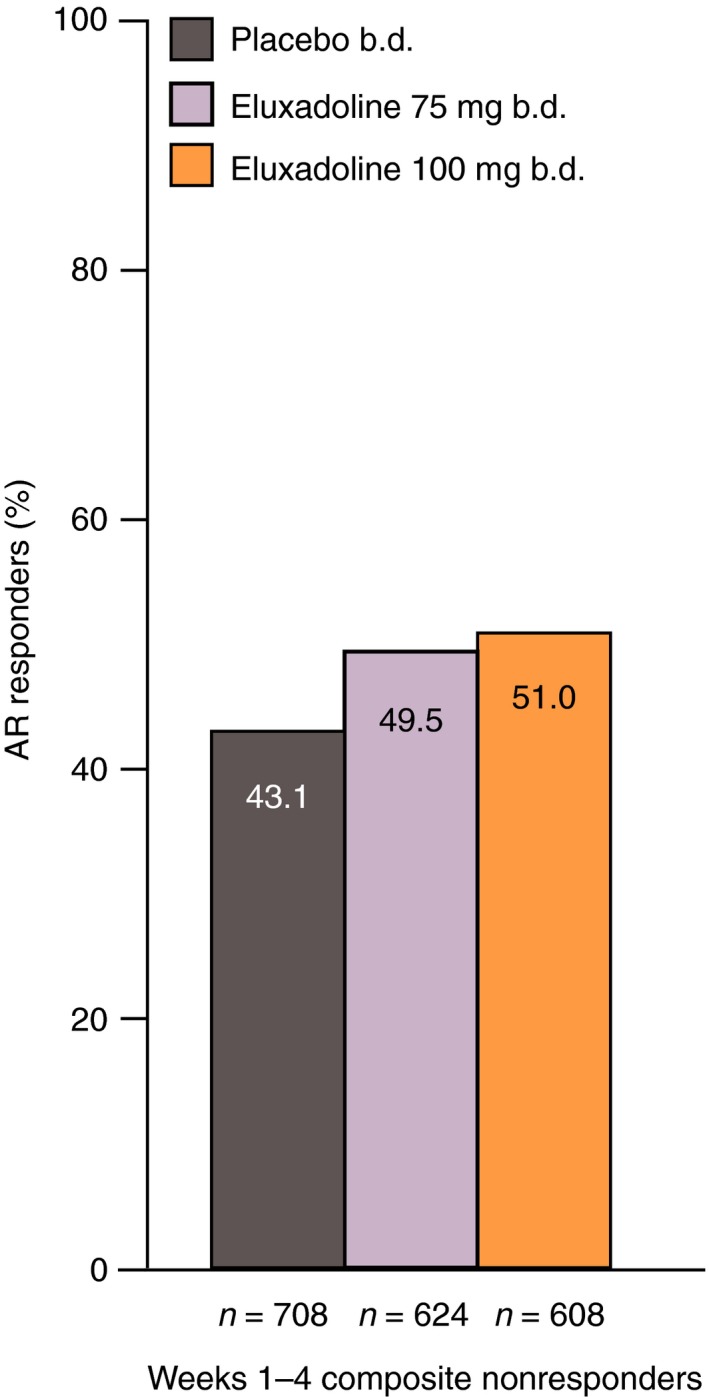

AR response rate among composite nonresponders

Of the patients who were not composite responders over month 1 (weeks 1–4) (eluxadoline 100 mg: 75.4%; eluxadoline 75 mg: 77.2%; placebo: 87.5%), ~50% did demonstrate clinical benefit with eluxadoline based on the AR responder endpoint over the same time period (eluxadoline 100 mg: 51.0%; eluxadoline 75 mg: 49.5%); proportions of responders receiving placebo were slightly lower (43.1%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proportions of weeks 1–4 composite nonresponders who were AR responders over weeks 1–4: pooled analysis of Phase 3 studies. Composite response is based on daily improvement of ≥30% in worst abdominal pain score compared with average baseline pain and, on the same day, a Bristol Stool Form Scale score of <5, on ≥50% of treatment days. AR response is defined as a ‘yes’ response to the following question: ‘Over the past week, have you had AR of your IBS symptoms?’. AR, adequate relief; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Discussion

For drugs approved for continuous use to treat a chronic illness, it is important for prescribers to understand the potential time course of clinical benefits, including the time to onset and the sustainability over time. Knowledge about whether patients who achieve clinical benefit early in treatment retain that response over time, and whether patients who fail to achieve an early benefit may develop a positive response at a later time, is critical in establishing reasonable expectations about the effectiveness of treatment.

Many clinical development programmes, including eluxadoline for IBS‐D, are not prospectively designed to answer such questions, since the primary focus is on the regulatory endpoint(s) necessary for approval. Because of the waxing and waning character of IBS symptoms, it is recommended by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) that patient‐level overall responses to IBS treatments are determined over a specified interval (no less than 8 weeks for the FDA and 26 weeks for the EMA for drugs intended for chronic, continuous use), with patients required to meet the response criteria for ≥50% of this time. Furthermore, the minimal time interval for effectiveness has historically been no less than 4 weeks, limiting the ability to determine time to onset of benefit.

Moreover, the regulatory endpoint of composite response, whether analysed over 3 or 6 months, may underestimate treatment benefit. The composite response endpoint is based on simultaneous improvement in both abdominal pain and stool consistency, over either the 3‐ or 6‐month period, resulting in an outcome measure that may be difficult for prescribers to put into clinical context. Additionally, it only assesses two IBS symptoms and may not provide a perspective of overall patient wellbeing and satisfaction, in contrast to a global symptom assessment such as AR. The AR endpoint may therefore be more relevant to the prescribing physician and the patient, as well as being easier to comprehend; however, it is no longer in favour from a regulatory standpoint due to its dependence on distant patient recall and inability to detect improvement or worsening of specific symptoms.

As previously published, data from the two eluxadoline Phase 3 trials demonstrated that prospectively analysed monthly assessments for the composite endpoint were comparable to the results over the full 6 months (weeks 1–26) of efficacy evaluation. Note that the monthly responder rates over time in Lembo et al. are driven by the population that met the responder criteria at each independent monthly interval.14 In contrast, the current analysis takes an alternative approach, assessing only the subpopulation of patients who were responders in the first month for a response in subsequent months.

It is important to note that for all of these analyses, the placebo effect is prominent and the response in the placebo arm parallels the findings in the active arms. However, these retrospective analyses were not intended to demonstrate separation from placebo, but rather to assess how the population of patients who either did or did not respond in month 1 fared over the remainder of the study, independent of treatment. The similarity seen between the active and placebo arms is not unexpected and may be related to selection bias, since the analysis population for continued response over subsequent months included only month 1 responders or month 1 nonresponders.

Despite possible selection bias, these data strongly suggest that the response in the placebo arm is both early and maintained, as is true for the active treatment arms. Factors underlying the response in the placebo arm will also contribute in part to the response seen in the active treatment arms. An explanation for this sustained placebo response underlying all treatment arms is unclear, but could be related to: regression of IBS symptoms to their respective means; the power of suggestion originating from ‘response fatigue’ or response shift due to daily responses over 6 months to the same symptom questions; a true physiological effect of placebo; or latent effects unmeasured in the current studies.

Alternatively, disease variation, which again will affect both active and placebo treatment arms, may have contributed to this finding. A previous study has demonstrated considerable variability in the natural history of IBS, with 32–68% of patients showing an improvement in their symptoms over the course of long‐term follow‐up,8 suggesting that a degree of variation and/or improvement in symptom severity attributable to the underlying disease course is to be expected, regardless of treatment arm. Similarly, it has been shown that while 62.2% of patients with IBS‐D followed up for 10 months continued to show symptoms consistent with IBS‐D, the remainder switched to the constipation subtype (7.7%), mixed subtype (7.0%) or unspecified subtype (23.1%).17

As shown in Figure 2, regardless of treatment arm, >65% of subjects who were composite responders within month 1 remained responders over the full duration of 6 months (weeks 1–26), with nearly identical results seen when evaluating the AR endpoint (Figure 5). This was further corroborated by the monthly assessments, which demonstrated that >60% of subjects who showed a composite response in month 1 of therapy, and ~70% who showed an AR response, remained responders for ≥3 of the five remaining months (Figures 4 and 7).

For those subjects who were composite nonresponders over month 1, 18% of subjects receiving eluxadoline 100 mg were subsequent composite responders over months 1–6 (weeks 1–26), vs. 13% for placebo (Figure 3). Similar findings were noted for the AR nonresponders over month 1, whose subsequent responder rate over months 1–6 (weeks 1–26) was ~17% for the active arms, albeit with less prominent separation from placebo (Figure 6).

Our results both corroborate Lembo et al.'s findings14 and demonstrate the robustness of the data. Specifically, these analyses suggest that a response during the first month after initiating eluxadoline treatment in IBS‐D appears to be predictive of a sustained response.

Additionally, Lembo et al. depict in their Figure 2 that the treatment effect observed for the composite endpoint occurred within the first few days of treatment, with the proportion of responders on active treatment being greater than placebo and the separation from placebo remaining constant over the 6‐month assessment period.14 A similar pattern of response over time is seen when plotting the weekly assessments of AR response (our Figure 1), although the ranges of response are notably higher than with the composite response.

The endpoints depicted in these two graphs are different both from a standpoint of definition (AR for the present Figure 1 vs. the composite endpoint of improvement in pain and stool consistency for Lembo et al. Figure 2, 14) as well as the timing of assessments (weekly for the AR endpoint with ≥50% of weeks positive and daily for the composite endpoint with ≥50% of days positive). Both the AR and composite endpoints qualitatively demonstrate a rapid onset that is not detectable by assessments evaluated over 50% of a time interval.

Based on the above, clinicians can employ both of these endpoints despite the differing rates of response. Therefore, the AR approach can be used, that is, a simple yes/no question, to assess response instead of the more cumbersome composite endpoint, which requires a daily diary record of stool consistency and pain scores. This is critical for appreciating the benefit of eluxadoline, as AR is an endpoint that clinicians and patients understand and it can easily be adapted for day‐to‐day practice.

Our data support that a trial of eluxadoline for at least 1 month to assess response is reasonable in patients with IBS‐D. Thirteen to 18% of nonresponders by either criteria (composite responder or AR responder) over the first month of treatment ultimately show a composite response over the remaining 5 months, suggesting that continuing therapy may offer minimal benefit to patients. The majority of patients who respond by either set of criteria over the first month of treatment retain their positive response over 6 months of treatment, thus a response in the first month bodes well for the continuation of response over time.

Authorship

Guarantor of the article: W.D. Chey.

Author contributions: PSC and LSD contributed towards study design; PSC, LSD, WDC and DAA contributed towards the planning of the described post hoc analyses; DAA contributed towards data analysis; and PSC, LSD, WDC and DAA contributed towards the writing of the manuscript.

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. The authors take full responsibility for the scope, direction and content of the manuscript and have approved the submitted manuscript, including the authorship list.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Catherine Gutman for her assistance in the development and interpretation of these analyses.

Declaration of personal interests: William D. Chey has received grant support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Perrigo Fny, Prometheus Laboratories and Nestlé, has served as an advisor or consultant for Actavis, Inc., an affiliate of Allergan plc, AstraZeneca, Astellas, Asubio, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Furiex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., an affiliate of Allergan plc, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Salix Pharmaceuticals, S K Pharmacare, Sucampo and Takeda, and has served as a speaker for the GI Health Foundation. David A. Andrae is an employee of Allergan plc. Paul S. Covington has acted as a scientific consultant for Actavis, Inc., an affiliate of Allergan plc. Leonard S. Dove serves as a scientific consultant for Allergan plc. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. Writing support was provided by Helen Woodroof, PhD, of Complete HealthVizion, Inc. and funded by Allergan plc.

Declaration of funding interests: None.

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Roy Pounder, and it was accepted for publication after full peer‐review.

References

- 1. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1480–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA 2015; 313: 949–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 712–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, et al Characteristics of functional bowel disorder patients: a cross‐sectional survey using the Rome III criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 312–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6: 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm 2004; 10: 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel P, Bercik P, Morgan DG, et al Irritable bowel syndrome is significantly associated with somatisation in 840 patients, which may drive bloating. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El‐Serag HB, Pilgrim P, Schoenfeld P. Natural history of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19: 861–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nellesen D, Yee K, Chawla A, Lewis BE, Carson RT. A systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Manag Care Pharm 2013; 19: 755–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paré P, Gray J, Lam S, et al Health‐related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006; 28: 1726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. US Food and Drug Administration. Viberzi . Highlights of prescribing information. 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206940s000lbl.pdf (accessed 5 October 2016).

- 12. Galligan JJ, Akbarali HI. Molecular physiology of enteric opioid receptors. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 2: 17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wade PR, Palmer JM, McKenney S, et al Modulation of gastrointestinal function by MuDelta, a mixed μ opioid receptor agonist/μ opioid receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 167: 1111–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, et al Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 242–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision. DSM‐IV‐TR. 4th ed Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press Ltd, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Department of Health and Human Services . NIAAA Newsletter. Winter 2004, Number 3. 2004. Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/newsletters/Newsletter_Number3.pdf (accessed 1 May 2016).

- 17. Garrigues V, Mearin F, Badía X, et al Change over time of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, observational, 1‐year follow‐up study (RITMO study). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]