Abstract

Background

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a prohormone that rises in bacterial pneumonia and has promise in reducing antibiotic use. Despite these attributes, there are inconclusive data on its use for clinical prognostication. We hypothesize that serial PCT measurements can predict mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and bacteremia.

Methods

A prospective cohort study of inpatients diagnosed with pneumonia was performed at a large tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts. Procalcitonin was measured on days 1 through 4. The primary endpoint was a composite adverse outcome defined as all-cause mortality, ICU admission, and bacteremia. Regression models were calculated with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) as a measure of discrimination.

Results

Of 505 patients, 317 patients had a final diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) or healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). Procalcitonin was significantly higher for CAP and HCAP patients meeting the composite primary endpoint, bacteremia, and ICU admission, but not mortality. Incorporation of serial PCT levels into a statistical model including the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) improved the prognostic performance of the PSI with respect to the primary composite endpoint (AUC from 0.61 to 0.66), bacteremia (AUC from 0.67 to 0.85), and need for ICU-level care (AUC from 0.58 to 0.64). For patients in the highest risk class PSI >130, PCT was capable of further risk stratification for prediction of adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

Serial PCT measurement in patients with pneumonia shows promise for predicting adverse clinical outcomes, including in those at highest mortality risk.

Keywords: bacteremia, biomarker, pneumonia, procalcitonin, prognosis

Pneumonia is a significant cause of morbidity, accounting for 1.1 million admissions annually in the United States with an average length of stay of 5.2 days and annual healthcare costs of $10.6 billion [1, 2]. Pneumonia is also the eighth leading cause of death with 53000 deaths in the United States and 3.1 million deaths globally [3, 4].

Scoring systems to predict 30-day mortality, such as the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), exist [5], and although informative, the PSI is cumbersome requiring 20 data points, including age that may underrecognize severe illness in younger patients [5]. Finally, the PSI was validated for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP); therefore, it may not be generalizable to patients who meet criteria for healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) [5].

Biomarkers are objective adjuncts to making the diagnosis of pneumonia. The biomarker procalcitonin (PCT) is a polypeptide precursor of calcitonin, which is produced ubiquitously by parenchymal cells in response to inflammatory cytokines with a rapid rise in the setting of bacterial infection [6]. In contrast, viral infections result in downregulation of PCT synthesis, an effect mediated by interferon-γ [7–9].

The ability of PCT to distinguish bacterial from viral etiologies of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) is established [10–13]. In addition, studies have demonstrated that the use of PCT-guided algorithms can safely reduce antibiotic exposure in LRTI without an increase in adverse events [10, 11, 14–16].

Although the role of PCT in the initial evaluation of LRTI is recognized, the contribution of PCT to clinical prognosis has yet to be defined. Several studies demonstrate an association between elevated PCT and mortality in septic patients [17, 18]. Although the addition of initial PCT to clinical indices improves prognostic performance of severity scores [19, 20], a large European study failed to validate these findings [21]. Herein, we sought to characterize the prognostic role of serial PCT measurements in patients admitted with pneumonia for the composite primary endpoint of death, need for intensive care unit (ICU)-level care, and bacteremia.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

We conducted a prospective cohort study of patients admitted to a 999-bed tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts from March to September 2013. Eligible patients were admitted for at least 1 night with findings on chest imaging consistent with pneumonia. Exclusion criteria included age <18, prior hospitalization within 14 days, concurrent ST-elevation myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, trauma or burns, requirement for emergent surgical intervention, and recent surgery. Procalcitonin was measured on days 1 through 4. The study was granted a waiver of informed consent by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board (Protocol no. 2012P001590).

Patient Screening and Selection

RENDER software [22] identified chest radiology reports from the Emergency Department that included the term “pneumonia”. After enrollment, chart review was performed by 2 independent physician reviewers, blinded to PCT values, to confirm a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia. Discordant adjudications were reviewed by committee (including an Infectious Diseases specialist) for final diagnosis.

Procalcitonin Measurement

The VIDAS B-R-A-H-M-S PCT (bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC), an enzyme-linked fluorescent assay with a detection range of <0.05 ng/mL to >200 ng/mL, was used to measure plasma PCT. If insufficient sample volume was encountered, PCT was not recorded for that study day. If multiple samples were available, the earliest sample was used.

Data Collection

Using REDCap [23], a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant data entry platform, clinical data were collected and independently verified including demographics, medical comorbidities, social history, initial vital signs, laboratory values, imaging findings, need for ICU-level care, and mortality. Pneumonia Severity Index was calculated for each study patient. The primary endpoint for the study was a composite outcome, defined as all-cause mortality, need for ICU-level care, or bacteremia.

Statistical Analysis

Overall population and subgroup analysis were performed based on final diagnosis of CAP or HCAP and of patients with PSI >130. Discrete variables were expressed as counts (percentage) and continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges. Frequency comparison was accomplished using the χ2 test. Mann-Whitney U test was applied for 2-group comparison for continuous data. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to study the association between PCT levels (days 1 through 4) and primary endpoints. We adjusted for PSI in the multivariate analysis to correct for comorbidities that comprise the score. Area under the receiver-operating-characteristics (ROC) curve (AUC) was calculated to assess overall discrimination. To determine whether PCT improves the performance of PSI, ROC curves of the joint logistic regression of PCT and the PSI (including a model combining PCT values for all days) were compared with ROC curves limited to PSI alone. All analyses were performed on STATA 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P values less than .05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Missing data points were not extrapolated.

RESULTS

Patient Population

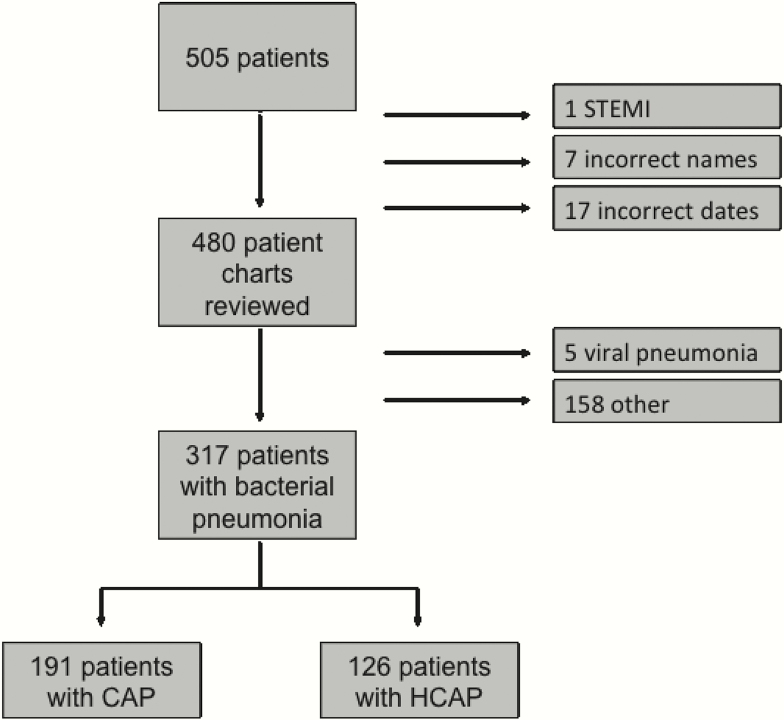

A total of 505 patients were enrolled. Twenty-five patients were excluded by criteria and sample errors. Four hundred eighty charts were reviewed by physicians blinded to PCT values, 20.4% of which ultimately required adjudication by committee to determine a final diagnosis. Of all patients, 191 (39.7%) were diagnosed with CAP, 126 (26.2%) with HCAP, 5 with viral pneumonia, and 158 (32.9%) with a condition other than pneumonia (Figure 1). Only patients with a final diagnosis of bacterial CAP or HCAP (n = 317) were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; HCAP, healthcare-associated pneumonia; STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Of the 317 pneumonia patients, 25% met the composite primary endpoint. Sixteen patients died, 16 had bacteremia, and 65 required ICU-level care. Of those requiring ICU-level care, 36 required vasopressors, 27 required mechanical ventilation, and 22 required both of these critical care interventions. Baseline characteristics of patients who met the composite endpoint were similar to those who did not in regards to age, gender, race, smoking status, and underlying comorbidities (Table 1). An exception was nursing home residents, who comprised a higher proportion of those meeting the composite endpoint. Likewise, a greater proportion of patients meeting the combined endpoint had HCAP rather than CAP (63% versus 38%, P < .01). Despite these differences at the time of admission, PSI was similar for the 2 groups.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics

| Variable | Meeting Endpoint | Not Meeting Endpoint | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 80 | n = 237 | P Value | |

| Age | 66 (26–95) | 68 (22–100) | .41 |

| Male | 54 (68) | 139 (59) | .16 |

| Race | .64 | ||

| White | 52 (65) | 161 (68) | |

| African American | 4 (5) | 12 (5) | |

| Asian | 3 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (8) | 10 (4) | |

| Other | 16 (20) | 50 (21) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 18 (23) | 55 (23) | .90 |

| Heart Failure | 17 (21) | 47 (20) | .78 |

| Renal Failure | 16 (20) | 52 (22) | .71 |

| On hemodialysis | 3 (4) | 6 (3) | |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (3) | 12 (5) | .27 |

| Malignancy | 35 (44) | 80 (34) | .11 |

| Underlying lung disease | |||

| Asthma | 15 (19) | 34 (14) | .35 |

| COPD | 20 (25) | 78 (33) | .19 |

| ILD | 6 (8) | 9 (4) | .18 |

| Lung cancer | 10 (13) | 20 (8) | .28 |

| Living Situation | <.01 | ||

| Home | 53 (66) | 199 (84) | |

| Assisted Living | 1 (1) | 9 (4) | |

| Nursing Facility | 21 (26) | 13 (5) | |

| Other | 3 (4) | 13 (5) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 3 (1) | |

| Active smoker | 17 (21) | 60 (25) | .46 |

| Type of Pneumonia | <.01 | ||

| CAP | 30 (38) | 161 (68) | |

| HCAP | 50 (63) | 76 (32) | |

| PSI | .36 | ||

| <70 | 2 (3) | 9 (4) | |

| 71–90 | 5 (6) | 20 (8) | |

| 91–130 | 27 (34) | 99 (42) | |

| >130 | 46 (58) | 109 (46) | |

Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCAP, healthcare-associated pneumonia; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PSI, Pneumonia Severity Index.

aData are presented as mean (range) or n (%). P value for age was calcuated using a t test. P values for categorical variables were calcuated from χ2 analyses.

Procalcitonin Range for Outcomes

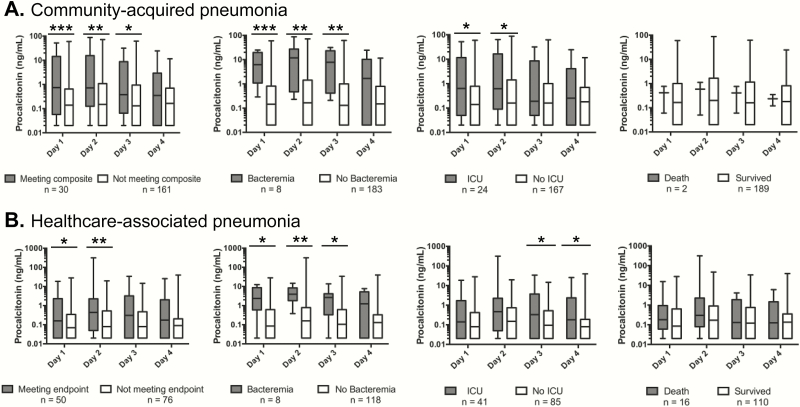

Procalcitonin measurements ranged from <0.05 to 313.4 ng/mL. Patients with CAP who met the composite endpoint had significantly higher PCT values on days 1 through 3, whereas patients with HCAP who met the endpoint had higher values on days 1 and 2 (Figure 2). Procalcitonin values for the components of the composite endpoint revealed that CAP patients requiring ICU-level care had significantly elevated PCT values on days 1 and 2, as opposed to days 3 and 4 for HCAP. Patients with bacteremia had higher PCT levels across all days for both CAP and HCAP. There was no significant difference in PCT values for patients who died versus those who survived (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Box plot representing the range, median, and first through third quartiles of procalcitonin values on hospital days 1 through 4 for patients with community- acquired pneumonia (A) and healthcare-associated pneumonia (B) who met the composite endpoint, developed bacteremia, required intensive care unit (ICU)-level care, or died. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Adverse Outcomes Associated With Elevated Procalcitonin

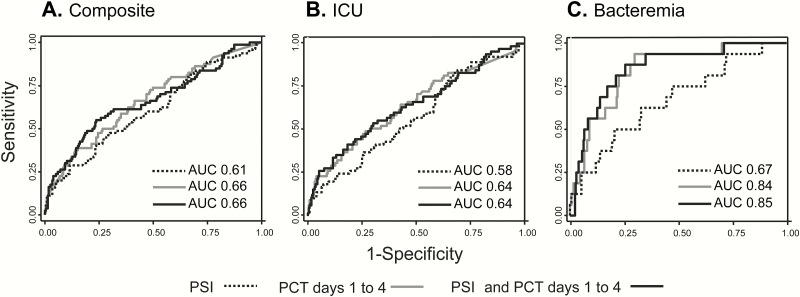

We next determined the ability of PCT to predict the composite endpoint as well as each individual component. A model combining PCT values on days 1 through 4 improved PCT performance when compared with PCT for any individual day (Supplemental Table 1). Using this combined PCT model to predict the composite primary endpoint, the AUC value was 0.66 for the total population (AUC 0.69 for CAP, 0.67 for HCAP). The AUC for the combined PCT model to predict the need for ICU-level care was 0.64 for the total population (AUC 0.65 for CAP, 0.67 for HCAP), and for bacteremia, the AUC was 0.84 for the total population (AUC 0.91 for CAP, 0.81 for HCAP) (Supplemental Table1, Figure 3). Serial measurements of PCT did not predict mortality.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the performance of the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) alone versus a model of serial procalcitonin (PCT) values versus a combination of serial PCT values with the PSI to determine the composite study endpoint (A), need for intensive care unit (ICU)-level care (B), and bacteremia (C).

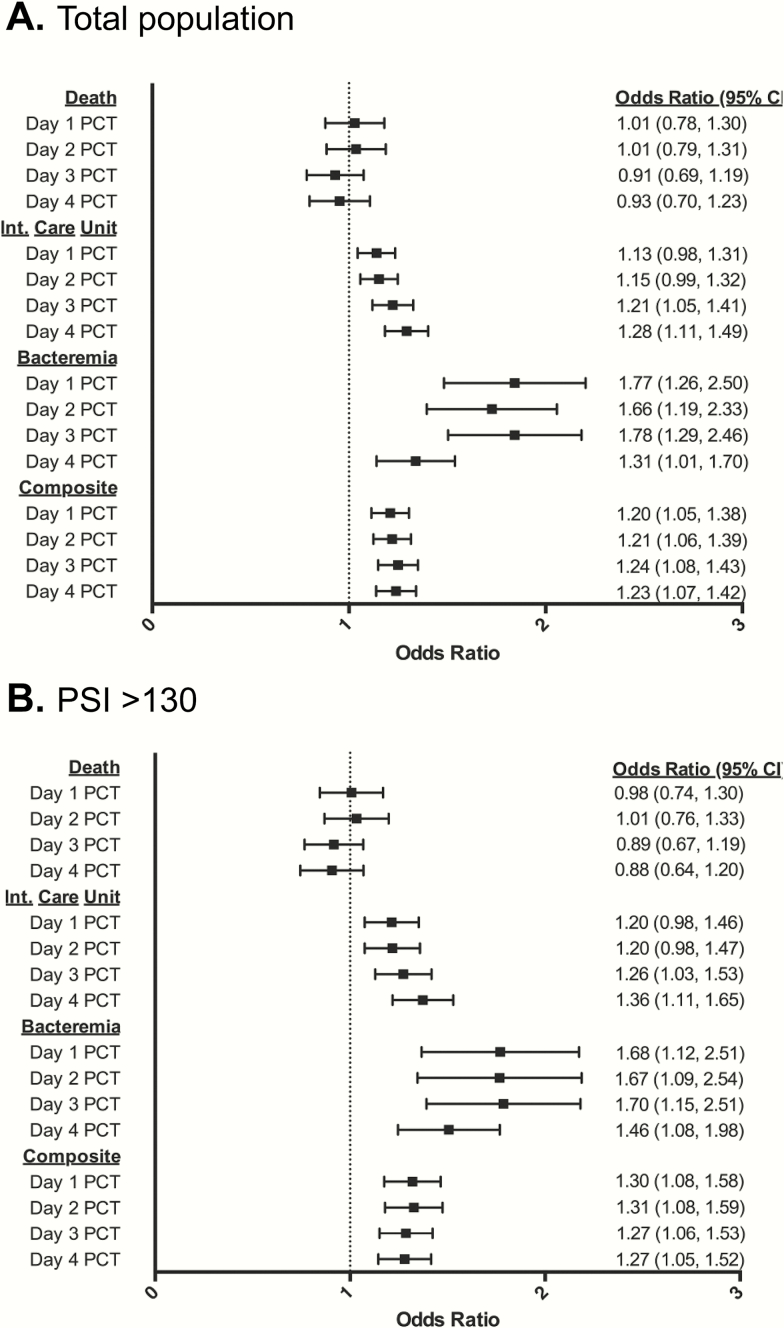

Odds ratios (OR) for study endpoints were determined after multivariate logistic regression of PCT, corrected for the PSI, including each determinant (Supplemental Table 2). Elevated PCT values were predictive of bacteremia in the total population with OR ranging from 1.31 to 1.78 (Figure 4A) and in patients with CAP with OR ranging from 1.34 to 2.62 (Supplemental Table 2). Procalcitonin also predicted need for ICU care, with peak effect seen on days 3 and 4 in the total population and patients with HCAP with OR of 1.21 to 1.28 and 1.24 to 1.40, respectively (Figure 4A, Supplemental Table 2). For the composite endpoint, PCT predicted adverse events across all days in both the total population and in patients with CAP with OR ranging from 1.2 to 1.24 and 1.24 to 1.35, respectively (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 4.

Multivariate regression analysis of the predictive value of procalcitonin (PCT) on hospital days 1 through 4 for death, need for intensive care unit-level care, bacteremia, and the composite endpoint in the total study population (n = 317) (A) and in patients with Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) >130 (n = 155) (B).

Impact of Procalcitonin on the Performance of the Pneumonia Severity Index

To determine whether PCT enhances PSI performance, we used a joint logistic regression model combining serial PCT (all days) and the PSI. The addition of serial PCT improved PSI’s ability to predict the composite endpoint with an AUC of 0.66, compared with the PSI alone with an AUC of 0.61 (Figure 3A). The combined model had an AUC of 0.64 compared with 0.58 for PSI alone in determining need for ICU-level care and 0.85 compared with 0.67 for bacteremia (Figure 3B and C).

Using Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Procalcitonin Cutoffs for Prognosis

Several studies have validated PCT cutoff values of 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 ng/mL to determine the probability of bacterial pneumonia [10–12, 14, 24]. According to these studies, cutoff of 0.1 ng/mL is unlikely to represent bacterial infection, whereas levels greater than 0.25–0.5 ng/mL are more likely to represent bacterial pneumonia. In our study, we evaluated the performance of day 1 PCT at these cutoff values to predict study endpoints. For the total population at PCT values of 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 ng/mL, sensitivity was 63%, 54%, and 46%, respectively, for the composite endpoint (Supplemental Table 3), all with negative predictive values (NPVs) >80%. High NPV was also seen for the primary endpoint components of death, need for ICU-level care, and bacteremia at all PCT cutoffs. The specificity of PCT-based prognosis using these predetermined cutoff values was highest when evaluating the HCAP subpopulation, whereas sensitivity was highest in the CAP subpopulation.

Procalcitonin-Based Prediction of Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Severe Disease

One hundred fifty-five study patients (49%) had PSI >130, placing them into the highest risk PSI category. In this group, we found that PCT continues to provide additional prognostic information, beyond the PSI. In the PSI >130 group, PCT was a significant predictor of the composite endpoint, as well as bacteremia on all days 1 though 4, with OR ranging from 1.27 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.52) to 1.31 (95% CI, 1.08–1.59) and 1.46 (95% CI, 1.08–1.98) to 1.70 (95% CI, 1.15–2.51), respectively. For ICU-level care, PCT was a predictor on hospital days 3 and 4 (Figure 4B). In a multivariate regression model combining all PCT days, AUCs were 0.70, 0.69, and 0.81 for the composite endpoint, need for ICU-level care, and bacteremia, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). In addition, joint logistic regression analysis showed that PCT significantly improves PSI performance for the composite endpoint (AUC 0.63 to 0.72, P = .05), need for ICU-level care (AUC 0.58 to 0.7, P = .05), and bacteremia (AUC 0.59 to 0.83, P = .01).

DISCUSSION

Few studies have investigated the prognostic value of PCT [17, 25, 26]. To our knowledge, these data represent the largest study in North America evaluating the prognostic potential of serial PCT levels in hospitalized patients with CAP and HCAP.

Despite an inability to predict all-cause mortality with PCT, we find that PCT accurately prognosticates the composite endpoint, which is driven by need for ICU-level care and bacteremia. Our data are consistent with others demonstrating that elevated PCT predicts bacteremia [27–29]. In regards to bacteremia, applying the suggested LRTI cutoff values of PCT >0.25 ng/mL and PCT >0.5 ng/mL, our results show PCT sensitivities of 87.5% and 81.3% with NPV of 99% and 98.6%, respectively. Our study supports the use of serial PCT values over a single time point for predicting adverse outcomes (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 1), although transition to clinical practice requires future research. We are aware of the Procalcitonin Monitoring Sepsis Study (MOSES, NCT01523717), which is a multicenter trial that highlights the utility of serial versus single PCT measurements when assessing prognosis in sepsis.

In addition to CAP, we investigated the role of PCT in patients with HCAP, a group with limited investigation in this field [30, 31]. It is interesting to note that there was no significant difference between PCT values for patients with CAP and HCAP. Elevated PCT levels were associated with adverse events, suggesting that PCT can be generalized to both pneumonia populations. Of the endpoints, we found that PCT is a better predictor of bacteremia and overall adverse events in patients with CAP versus HCAP. In contrast, PCT was a better predictor of ICU need in patients with HCAP, but later in the hospitalization (day 4), which may reflect host-specific immunity or bacterial etiology, both of which require further investigation.

Patients in the highest PSI risk category (PSI >130, class V) represent a significant portion of patients admitted with pneumonia [5] and the largest in our study (49% of the total population). Procalcitonin was able to further risk stratify patients in this highest PSI class (Figure 4). Other studies have also found that PCT can be used for the evaluation of high-risk patients with pneumonia [25, 32], opening the possibility of more efficient healthcare use in this patient population.

The PCT cutoff values of 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 ng/mL have been described in the determination for LRTI and PCT-guided antimicrobial therapy [10, 11, 14]. We sought to determine whether these cutoffs were applicable for prognostication. Despite 46% of patients who met the primary endpoint having day 1 PCT values greater than 0.5 ng/mL, the accepted lower cutoffs for LRTI resulted in a striking NPV of >80%. The positive predictive value ranged up to 50%, suggesting that an optimal cutoff for meeting an endpoint in our patient population is likely higher than 0.5 ng/mL. Furthermore, optimal cutoffs to predict adverse events may depend upon each specific patient population, which in this study trended toward patients with severe illness.

Despite several studies investigating serial PCT as a prognostic biomarker for mortality, data remain inconclusive [33–35]. Both an early rise in PCT [17] as well as persistent elevations in PCT have been shown to be independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality [34]. In contrast, a large study in Denmark [33] found that an initial PCT did not predict 90-day mortality. Likewise, our findings reveal that PCT does not independently predict mortality, nor does it improve the PSI in assessing this outcome, although our overall mortality is low at 5.7% and may be underpowered.

Limitations to our study include a single large tertiary care institution study with a heterogeneous patient population. We also note that the study period did not capture the influenza season, which may have provided additional insight regarding severe viral pneumonia and bacterial superinfection. Finally, given the observational study design, data were limited by availability of information in the medical record, and clinical providers did not have PCT results available to guide management. Prospective studies in which providers have PCT results available in real time will be required to define the number and frequency of PCT measurements to predict prognosis. Additional research focused on applying PCT-based prognostication to the effective use of healthcare resources is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study expands the ability of serial PCT values to improve the performance of clinical scores such as the PSI to predict need for ICU-level care and bacteremia. We also show that although still useful in patients with HCAP, the overall prognostic performance of PCT is best in the CAP population. Finally, this study highlights the utility of serial PCT measurements to predict adverse events in patients who fall into the highest PSI severity class.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary material is available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from bioMérieux (to M. K. M. and J. M. V.). P. S. is supported in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Professorship, PP00P3_150531/1) and received research grants from BRAHMS/Thermofisher, Roche, Abbott, and bioMérieux.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number and rate of discharges from short-stay hospitals and of days of care, with average length of stay and standard error, by selected first-listed diagnostic categories. CDC/NCHS National Hospital Discharge Survey. 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/2average/2010ave2_firstlist.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. Costs for Hospital Stays in the United States, 2011: Statistical Brief #168. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:415–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2016; 64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J 2007; 30:556–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Linscheid P, Seboek D, Nylen ES, et al. In vitro and in vivo calcitonin I gene expression in parenchymal cells: a novel product of human adipose tissue. Endocrinology 2003; 144:5578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Becker KL, Snider R, Nylen ES. Procalcitonin assay in systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis: clinical utility and limitations. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:941–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Becker KL, Nylén ES, White JC, et al. Clinical review 167: procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:1512–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet 2004; 363:600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174:84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest 2007; 131:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stolz D, Stulz A, Müller B, et al. BAL neutrophils, serum procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein to predict bacterial infection in the immunocompromised host. Chest 2007; 132:504–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 302:1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 375:463–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schuetz P, Briel M, Christ-Crain M, et al. Procalcitonin to guide initiation and duration of antibiotic treatment in acute respiratory infections: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:651–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alba GA, Truong QA, Gaggin HK, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of procalcitonin in patients presenting to the emergency department with dyspnea. Am J Med 2016; 129:96–104.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kasamatsu Y, Yamaguchi T, Kawaguchi T, et al. Usefulness of a semi-quantitative procalcitonin test and the A-DROP Japanese prognostic scale for predicting mortality among adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology 2012; 17:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fernandes L, Arora AS, Mesquita AM. Role of semi-quantitative serum procalcitonin in assessing prognosis of community acquired bacterial pneumonia compared to PORT PSI, CURB-65 and CRB-65. J Clin Diagn Res 2015; 9:OC01–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park JH, Wee JH, Choi SP, Oh SH. The value of procalcitonin level in community-acquired pneumonia in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30:1248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schuetz P, Suter-Widmer I, Chaudri A, et al. Prognostic value of procalcitonin in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2011; 37:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dang PA, Kalra MK, Schultz TJ, et al. Informatics in radiology: render: an online searchable radiology study repository. Radiographics 2009; 29:1233–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Briel M, Schuetz P, Mueller B, et al. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic use vs a standard approach for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:2000–7; discussion 2007–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang DT, Weissfeld LA, Kellum JA, et al. Risk prediction with procalcitonin and clinical rules in community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52:48–58.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Procalcitonin Monitoring Sepsis Study (MOSES, NCT01523717).

- 27. Müller B, Harbarth S, Stolz D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic accuracy of clinical and laboratory parameters in community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis 2007; 7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chirouze C, Schuhmacher H, Rabaud C, et al. Low serum procalcitonin level accurately predicts the absence of bacteremia in adult patients with acute fever. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schuetz P, Mueller B, Trampuz A. Serum procalcitonin for discrimination of blood contamination from bloodstream infection due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Infection 2007; 35:352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi Y, Xu YC, Rui X, et al. Procalcitonin kinetics and nosocomial pneumonia in older patients. Respir Care 2014; 59:1258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dallas J, Brown SM, Hock K, et al. Diagnostic utility of plasma procalcitonin for nosocomial pneumonia in the intensive care unit setting. Respir Care 2011; 56:412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Masiá M, Gutiérrez F, Shum C, et al. Usefulness of procalcitonin levels in community-acquired pneumonia according to the patients outcome research team pneumonia severity index. Chest 2005; 128:2223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jensen JU, Heslet L, Jensen TH, et al. Procalcitonin increase in early identification of critically ill patients at high risk of mortality. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:2596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boussekey N, Leroy O, Alfandari S, et al. Procalcitonin kinetics in the prognosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32:469–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lacoma A, Rodríguez N, Prat C, et al. Usefulness of consecutive biomarkers measurement in the management of community-acquired pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 31:825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.