Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia are associated with increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and poor treatment outcomes. This post hoc evaluation of the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI) and complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI) aimed to evaluate baseline characteristics, efficacy, and safety in patients with and without diabetes treated with ceftolozane/tazobactam and comparators. Ceftolozane/tazobactam is an antibacterial with potent activity against Gram-negative pathogens and is approved for the treatment of cIAI (with metronidazole) and cUTI (including pyelonephritis).

Methods

Patients from the phase 3 ASPECT studies with (n = 245) and without (n = 1802) diabetes were compared to evaluate the baseline characteristics, efficacy, and safety of ceftolozane/tazobactam and active comparators.

Results

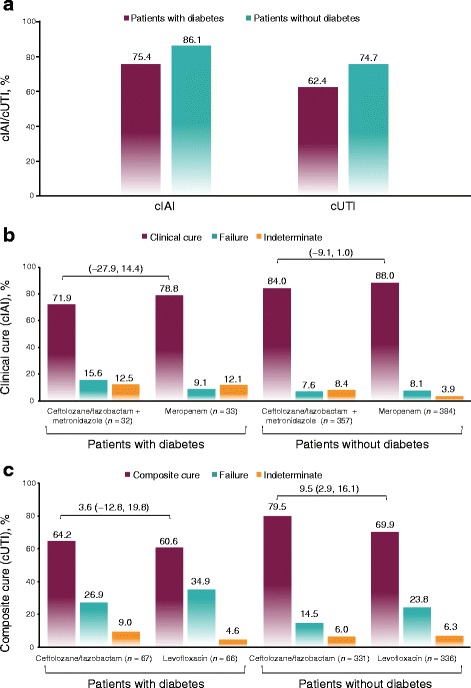

Significantly more patients with than without diabetes were 65 years of age or older; patients with diabetes were also more likely to weigh ≥75 kg at baseline (57.1% vs 44.5%), to have renal impairment (48.5% vs 30.2%), or to have APACHE II scores ≥10 (33.8% vs 17.0%). More patients with diabetes had comorbidities and an increased incidence of complicating factors in both cIAI and cUTI. Clinical cIAI and composite cure cUTI rates across study treatments were lower in patients with than without diabetes (cIAI, 75.4% vs 86.1%, P = 0.0196; cUTI, 62.4% vs 74.7%, P = 0.1299) but were generally similar between the ceftolozane/tazobactam and active comparator treatment groups. However, significantly higher composite cure rates were reported with ceftolozane/tazobactam than with levofloxacin in patients without diabetes with cUTI (79.5% vs 69.9%; P = 0.0048). Significantly higher rates of adverse events observed in patients with diabetes were likely due to comorbidities because treatment-related adverse events were similar between groups.

Conclusions

In this post hoc analysis, patients with diabetes in general were older, heavier, and had a greater number of complicating comorbidities. Patients with diabetes had lower cure rates and a significantly higher frequency of adverse events than patients without diabetes, likely because of the higher rates of medical complications in this subgroup. Ceftolozane/tazobactam was shown to be at least as effective as comparators in treating cUTI and cIAI in this population.

Trial registration

cIAI, NCT01445665 and NCT01445678 (both trials registered prospectively on September 26, 2011); cUTI, NCT01345929 and NCT01345955 (both trials registered prospectively on April 28, 2011).

Keywords: Ceftolozane/tazobactam, Complicated urinary tract infections, Complicated intra-abdominal infections, Diabetes mellitus

Background

In recent decades, the incidence and prevalence of diabetes have increased rapidly [1], with recent studies estimating that 422 million people worldwide are affected [2]. In addition to the burden directly imposed by the condition, patients with diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia have been shown to have increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and poor outcomes, including increased risk for hospitalization, reduced cure rates, and increased mortality due to infection [3, 4]. Furthermore, patients with diabetes commonly have comorbidities that may further affect their response to treatment; for example, both cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease appear to be predictors of lengthened hospital stay and infection-related mortality [5–7].

Ceftolozane/tazobactam, an antibacterial with potent activity against Gram-negative pathogens [8, 9], is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI) when used in combination with metronidazole and for the treatment of patients with complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI), including pyelonephritis [10, 11]. Ceftolozane/tazobactam was studied in a large phase 3 clinical trial program (Assessment of the Safety Profile and Efficacy of Ceftolozane/Tazobactam [ASPECT]) in patients with cIAI or cUTI. In ASPECT-cIAI (NCT01445665 and NCT01445678), ceftolozane/tazobactam plus metronidazole was noninferior to meropenem in patients with cIAI [12]. In ASPECT-cUTI (NCT01345929 and NCT01345955), ceftolozane/tazobactam demonstrated efficacy superior to that of high-dose levofloxacin in patients with cUTI [13].

Herein we present a post hoc investigation of baseline characteristics, efficacy, and safety from patients with or without a reported medical history of diabetes in the phase 3 ASPECT trials. The aims of this evaluation were to examine the baseline characteristics of patients with and without diabetes who were enrolled in the ASPECT trials and to assess whether ceftolozane/tazobactam was safe and effective in treating cIAI and cUTI in patients with diabetes.

Methods

Study design

Two multicenter, multinational, randomized (1:1 ratio), double-blind, noninferiority trials were conducted from 2011 to 2013 (Merck protocols: CXA-cIAI-10-08, CXA-cIAI-10-09, CXA-cUTI-10-04, and CXA-cUTI-10-05). Studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards and regulatory agencies [12, 13]. In ASPECT-cIAI, adults with cIAI in need of surgical intervention were assigned to receive intravenous (IV) ceftolozane/tazobactam 1.5 g plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 h (q8h) or IV meropenem 1 g plus placebo q8h for 4 to 14 days. In ASPECT-cUTI, adults with cUTI (including pyelonephritis) were assigned to receive IV ceftolozane/tazobactam 1.5 g q8h or IV levofloxacin 750 mg/day for 7 days.

Patients

Patients enrolled in the trials were classified into subgroups with and without diabetes, based on their reported medical history, and all analyses were evaluated between these two subgroups. Baseline demographics and characteristics were recorded descriptively. Between-group differences were determined, and statistical significance was calculated using the Miettinen and Nurminen method [14].

Efficacy assessments

In ASPECT-cIAI, clinical cure, defined as complete resolution or significant improvement in signs and symptoms of index infection with no additional antibiotics or surgical intervention, was assessed at the test-of-cure (TOC) visit (24–32 days after study drug start). In ASPECT-cUTI, composite cure, defined as both clinical cure (complete resolution or significant improvement in all signs and symptoms) and microbiologic eradication (reduction in all baseline uropathogens to <104 CFU/mL in urine culture) was assessed at the TOC visit (5–9 days after the end of therapy). For this analysis, clinical cure and composite cure rates were compared between patients with and without diabetes, with indeterminate responses imputed as clinical failures, and Wilson score intervals were used to calculate confidence intervals.

Safety assessments

Safety and tolerability were assessed by recording adverse events (AEs). AEs were categorized by the investigator as treatment related (possibly, probably, or definitely) or not treatment related. Data were recorded descriptively. Between-group differences were determined, and statistical significance was calculated using the Miettinen and Nurminen method [14].

Analysis populations

The cIAI microbiologic intention-to-treat population included all randomly assigned patients with cIAI with ≥1 baseline intra-abdominal pathogen regardless of receipt of, or susceptibility to, study drug. The cUTI microbiologic modified intention-to-treat population included all randomly assigned patients with cUTI with ≥1 dose of study drug and ≥1 uropathogen at baseline, regardless of susceptibility to study drug. The integrated safety population included all patients with cIAI or cUTI who received any amount of study drug.

Results

Patient population and disposition

The pooled analysis population comprised 979 patients from ASPECT-cIAI and 1068 patients from ASPECT-cUTI [12, 13], including 245 patients with diabetes and 1802 without diabetes. Patient disposition is shown in Table 1. Patient groups (with diabetes and without diabetes) had similar rates of study completion and study drug completion and similar reasons for discontinuation. In ASPECT-cUTI, negative/contaminated urine culture (12.1% and 18.8%, respectively) was the most common reason for early discontinuation of study drug, which was required per protocol.

Table 1.

Patient disposition (safety population)

| Disposition, n (%) | Diabetes n = 245 |

No diabetes n = 1802 |

|---|---|---|

| Patients completing the studies | 230 (93.9) | 1726 (95.8) |

| Most common reasons for premature withdrawal from the study | ||

| AEs | 5 (2.0) | 16 (0.9) |

| Patient’s decision | 6 (2.4) | 29 (1.4) |

| Patients completing study drug | 200 (81.6) | 1528 (84.8) |

| Most common reasons for discontinuing study drug | ||

| AEs | 8 (3.3) | 32 (1.8) |

| Patient’s decision | 7 (2.8) | 36 (2.0) |

| Lack of efficacy | 5 (2.0) | 11 (0.6) |

AE adverse event

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are reported in Table 2. In the subgroups with and without diabetes, most patients were white, and slightly more women than men were included. Patients were evenly distributed between treatment arms in the subgroups with and without diabetes (data not shown).

Table 2.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline (MITT/cIAI population and mMITT/cUTI population)

| Parameter | Diabetes n = 198 | No diabetes n = 1408 | Differencea; P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| cIAI, n (%) | 65 (32.8) | 741 (52.6) | — |

| cUTI, n (%) | 133 (67.2) | 667 (47.4) | — |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 73 (36.9) | 601 (42.7) | 5.8; 0.12061 |

| Female | 125 (63.1) | 807 (57.3) | −5.8; 0.12061 |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 60 (13.9) | 48 (18.9) | — |

| ≥ 18–<65, n (%) | 123 (62.1) | 1099 (78.1) | 15.9; <0.00001 |

| ≥ 65–<75, n (%) | 46 (23.2) | 166 (11.8) | −11.4; <0.00001 |

| > 75, n (%) | 29 (14.6) | 143 (10.2) | −4.5; 0.05581 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 159 (80.3) | 1282 (91.1) | 10.7; <0.00001 |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 17 (1.2) | 1.2; 0.12020 |

| Asian | 30 (15.2) | 64 (4.5) | −10.6; <0.00001 |

| Other | 9 (4.5) | 45 (3.2) | −1.4; 0.29496 |

| Geographic region, n (%) | |||

| North America | 17 (8.6) | 59 (4.2) | −4.4; 0.00640 |

| South America | 26 (13.1) | 127 (9.0) | −4.1; 0.06511 |

| Western Europe | 3 (1.5) | 27 (1.9) | 0.4; 0.69541 |

| Eastern Europe | 118 (59.6) | 1095 (77.8) | 18.2; <0.00001 |

| Rest of world | 34 (17.2) | 100 (7.1) | −10.1; <0.00001 |

| Weight, kg | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (17.2) | 74 (17.2) | −5.28; 0.00003 |

| ≥ 75 kg, n (%) | 113 (57.1) | 627 (44.5) | −12.5; 0.00092 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29 (5.8) | 26 (5.4) | −3.24; <0.00001 |

| APACHE II score (cIAI), N b | 65 | 740 | |

| < 10, n (%) | 43 (66.2) | 614 (83.0) | −16.8; <0.0008 |

| ≥ 10, n (%) | 22 (33.8) | 126 (17.0) | |

| Baseline creatinine clearance, n (%) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal, ≥80 mL/min | 101 (51.0) | 983 (69.8) | 18.8; <0.00001 |

| Impairment, <80 mL/min | 96 (48.5) | 425 (30.2) | — |

| Mild, ≥50 to <80 mL/min | 64 (32.2) | 359 (25.5) | −6.8; 0.04123 |

| Moderate, ≥30 to <50 mL/min | 31 (15.7) | 63 (4.5) | −11.2; <0.00001 |

| Severe, <30 mL/min | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | −0.3; 0.44038 |

| Disease type, n (%)c | |||

| cIAI, N | 65 | 741 | — |

| Acute gastric or duodenal perforation | 4 (6.2) | 67 (9.0) | 2.9; 0.43116 |

| Appendiceal perforation or periappendiceal abscess | 14 (21.5) | 364 (49.1) | 27.6; 0.00002 |

| Cholecystitis, including gangrenous | 21 (32.3) | 120 (16.2) | −16.1; 0.00105 |

| Diverticular disease with perforation or abscess | 8 (12.3) | 57 (7.7) | −4.6; 0.19036 |

| Traumatic perforation of the intestine | 0 (0.0) | 12 (1.6) | 1.6; 0.30158 |

| Peritonitis | 8 (12.3) | 66 (8.9) | −3.4; 0.36290 |

| Other intra-abdominal abscess | 10 (15.4) | 55 (7.4) | −8.0; 0.02388 |

| cUTI, N | 133 | 667 | — |

| Pyelonephritis | 106 (79.7) | 550 (82.5) | 2.8; 0.44971 |

| cLUTI | 27 (20.3) | 117 (17.5) | −2.8; 0.44971 |

| Treatment group, n (%)c | |||

| cIAI, N | 65 | 741 | — |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam + metronidazole | 32 (49.2) | 357 (48.2) | −1.1; 0.87072 |

| Meropenem | 33 (50.8) | 384 (51.8) | 1.1; 0.87072 |

| cUTI, N | 133 | 667 | — |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 67 (50.4) | 331 (49.6) | −0.8; 0.87444 |

| Levofloxacin | 66 (49.6) | 336 (50.4) | 0.8; 0.87444 |

APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, BMI body mass index, cIAI complicated intra-abdominal infection, cLUTI complicated lower urinary tract infection, cUTI complicated urinary tract infection, MITT microbiologic intention-to-treat, mMITT modified microbiologic intention-to-treat, SD standard deviation

aPercentage difference calculated for patients with history of diabetes versus those with no history of diabetes

bExpressed as a percentage of the patients with or without diabetes in the cIAI population only

cExpressed as a percentage of the patients with or without diabetes in the cIAI or cUTI population

Notable differences between patients with and without diabetes included age, weight, race, and comorbidities (Table 2). Significantly more patients with than without diabetes were 65 years of age or older; patients with diabetes were also significantly more likely (57.1%) to weigh ≥75 kg at baseline than those without diabetes (44.5%). In addition, there was a significantly higher proportion of Asian patients in the subgroup with diabetes than in the subgroup without diabetes. As expected, renal impairment was more common in the subgroup with diabetes (48.5%) than in the subgroup without it (30.2%); 15.7% of patients with diabetes had moderate renal impairment compared with 4.5% of patients without diabetes. In cIAI, a significantly higher percentage of patients with diabetes had Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores ≥10 (33.8% vs 17.0% in patients without diabetes), potentially driven by older age and decreased renal function. Additionally, cholecystitis was significantly more common in patients with diabetes; appendiceal infections were significantly more common in patients without diabetes.

A summary of medical history ongoing at baseline is shown in Table 3. As expected, cardiac, endocrine, and eye disorders were reported at significantly higher incidences in the subgroup with diabetes. For cardiac disorders, the major driver of the difference between patients with and without diabetes was coronary artery disorders (17.2% vs 7.6%); for eye disorders, the major driver was diabetic retinopathy (4.5% vs 0%).

Table 3.

Medical history ongoing at baseline (MITT/cIAI population and mMITT/cUTI population)

| System organ class, n (%)a | Diabetes | No diabetes | Differenceb; |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred term | n = 198 | n = 1408 | P value |

| Cardiac disorders | 50 (25.3) | 177 (12.6) | −12.7; <0.00001 |

| Coronary artery disorders | 34 (17.2) | 107 (7.6) | −9.6; <0.00001 |

| Heart failures | 15 (7.6) | 39 (2.8) | −4.8; 0.00045 |

| Endocrine disorders | 17 (8.6) | 57 (4.0) | −4.5; 0.00436 |

| Hypothyroidism | 14 (7.1) | 41 (2.9) | −4.2; 0.00260 |

| Eye disorders | 14 (7.1) | 33 (2.3) | −4.7; 0.00022 |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 9 (4.5) | 0 | −4.5; <0.00001 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 21 (10.6) | 82 (5.8) | −4.8; 0.01014 |

| Hepatic and hepatobiliary disorders | 13 (6.6) | 30 (2.1) | −4.4; 0.00030 |

| Infections and infestations | 55 (27.8) | 228 (16.2) | −11.6; 0.00006 |

| Urinary tract infections | 35 (17.7) | 119 (8.5) | −9.2; 0.00004 |

| Viral infectious disorders | 10 (5.1) | 25 (1.8) | −3.3; 0.00313 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 198 (100.0) | 166 (11.8) | −88.2; <0.00001 |

| Glucose metabolism disorders, including diabetes | 198 (100.0) | 16 (1.1) | −98.9; <0.00001 |

| Lipid metabolism disorders | 31 (15.7) | 62 (4.4) | −11.3; <0.00001 |

| Obesity | 13 (6.6) | 37 (2.6) | −3.9; 0.00282 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 32 (16.2) | 114 (8.1) | −8.1; 0.00022 |

| Joint disorders | 23 (11.6) | 64 (4.5) | −7.1; 0.00004 |

| Nervous system disorders | 34 (17.2) | 99 (7.0) | −10.1; <0.00001 |

| Peripheral neuropathies | 17 (8.6) | 1 (0.1) | −8.5; <0.00001 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 22 (11.1) | 79 (5.6) | −5.5; 0.00284 |

| Depressive disorders | 13 (6.6) | 33 (2.3) | −4.2; 0.00086 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 67 (33.8) | 245 (17.4) | −16.4; <0.00001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17 (8.6) | 19 (1.3) | −7.2; <0.00001 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 12 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | −6.1; <0.00001 |

| Urolithiases | 22 (11.1) | 81 (5.8) | −5.4; 0.00397 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 28 (14.1) | 87 (6.2) | −8.0; 0.00005 |

| Bronchospasm and obstruction | 17 (8.6) | 49 (3.5) | −5.1; 0.0007 |

| Vascular disorders | 140 (70.7) | 390 (27.7) | −43.0; <0.00001 |

| Hypertension | 131 (66.2) | 342 (24.3) | −41.9; <0.00001 |

cIAI complicated intra-abdominal infection, cUTI complicated urinary tract infection, MITT microbiologic intention-to-treat, mMITT modified microbiologic intention-to-treat

aOnly preferred terms with differences in rates between patients with and without diabetes are presented

bPercentage difference calculated for patients with history of diabetes compared with those with no history of diabetes

Significantly higher incidences of renal diseases and complications were also associated with diabetes, particularly chronic kidney disease (8.6% in patients with diabetes vs 1.3% in patients without diabetes) and diabetic nephropathy (6.1% vs 0%). The significantly higher incidence of vascular disorders in patients with diabetes (70.7% vs 27.7% in patients without diabetes) was largely driven by the incidence of hypertension (66.2% vs 24.3%). Patients with diabetes also had significantly more ongoing infections and more hepatic, nervous system, and respiratory disorders.

Bacteriology findings across subgroups with and without diabetes were generally similar within each indication (cUTI and cIAI; Table 4). Escherichia coli was the most common pathogen in both indications and subpopulations.

Table 4.

Baseline infecting intra-abdominal pathogens and uropathogens (MITT/cIAI population and mMITT/cUTI population)

| Pathogen,a n (%) | cIAI | cUTI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes n = 65 |

No diabetes n = 741 |

Diabetes n = 133 |

No diabetes n = 667 |

|

| Gram-negative aerobes | 46 (70.8) | 613 (82.7) | 127 (95.5) | 637 (95.5) |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 45 (69.2) | 577 (77.9) | 126 (94.7) | 613 (91.9) |

| Escherichia coli | 37 (56.9) | 488 (65.9) | 99 (74.4) | 530 (79.5) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0 (0.0) | 70 (9.4) | 14 (10.5) | 44 (6.6) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0 (0.0) | 68 (9.2) | 1 (0.8) | 22 (3.3) |

| Gram-positive aerobes | 38 (58.5) | 406 (54.8) | 6 (4.5) | 42 (6.3) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 16 (24.6) | 79 (10.7) | 4 (3.0) | 34 (5.1) |

| E. faecium | 0 (0.0) | 74 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.7) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 (0.0) | 27 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (0.6) |

| Gram-negative anaerobes | 24 (36.9) | 267 (36.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Bacteroides spp | 23 (35.4) | 228 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Gram-positive anaerobes | 7 (10.8) | 92 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

cIAI complicated intra-abdominal infection, cUTI complicated urinary tract infection, MITT microbiologic intention-to-treat, mMITT microbiologic modified intention-to-treat, NA, not applicable

aPatients could have had multiple infecting pathogens at baseline

Efficacy

In general, patients with diabetes had lower cure rates than patients without diabetes (cIAI, 75.4% vs 86.1%, P = 0.0196; cUTI, 62.4% vs 74.7%, P = 0.1299 [Fig. 1a]). However, cure rates were similar between treatment arms in both indications (Fig. 1b, c), with the exception of significantly higher composite cure rates for ceftolozane/tazobactam than for levofloxacin (79.5% vs 69.9%, P = 0.0048) in patients with cUTI but without diabetes (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Clinical cure (cIAI) and composite cure (cUTI) in patients with and without diabetes at test-of-cure in cIAI (MITT population) and cUTI (mMITT population) (a). Clinical cure at test-of-cure in cIAI (MITT population) (b). Composite cure at test-of-cure in cUTI (mMITT population) (c). Values above brackets indicate treatment difference (95% confidence intervals)

Safety

Patients with diabetes had significantly higher rates of AEs (49.0% vs 37.3%) and serious AEs (10.6% vs 4.6%) than patients without diabetes (Table 5). However, rates of treatment-related AEs were similar between patients with and without diabetes (8.2% vs 10.1%, respectively), suggesting comorbidities were responsible for differences in AE rates. Types of AEs were generally similar between patient subpopulations, but the incidences of infections and vascular disorders were significantly higher in patients with diabetes.

Table 5.

Summary of AEs (safety population)

| Parameter, n (%) | Diabetes n = 245 |

No diabetes n = 1802 |

P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 120 (49.0) | 673 (37.3) | 0.00046 |

| Any serious AE | 26 (10.6) | 82 (4.6) | 0.00007 |

| Any treatment-related AE | 20 (8.2) | 182 (10.1) | 0.34038 |

| Any treatment-related serious AE | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 0.46052 |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation of study drug | 8 (3.3) | 32 (1.8) | 0.11411 |

| Any treatment-related AE leading to discontinuation of study drug | 3 (1.2) | 13 (0.7) | 0.40162 |

| Any AE resulting in death | 6 (2.4) | 14 (0.8) | 0.01256 |

| Any treatment-related AE resulting in death | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00000 |

| System organ class AEs with significant difference between groups | |||

| Infections and infestations | 29 (11.8) | 137 (7.6) | 0.02277 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −4.2 (−9.0, −0.5) | ||

| Vascular disorders | 18 (7.3) | 69 (3.8) | 0.01046 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −3.5 (−7.6, −0.7) | ||

AE adverse event, CI confidence interval

aCalculated for patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of patients with or without a reported medical history of diabetes in the phase 3 ASPECT trials, we have shown that older age, increased weight, and renal impairment are more common in patients with diabetes than in patients without diabetes. In addition, more patients with diabetes had comorbidities and an increased incidence of complicating factors in both cUTI and cIAI, with cardiac, endocrine, and eye disorders reported at significantly higher incidences in the subgroup with diabetes. It has been reported that patients with diabetes are more susceptible to infections and associated complications because of a variety of factors, including but not limited to lower production of interleukins in response to infection and increased virulence of some pathogens in hyperglycemic environments [15].

In our analysis, clinical and composite cure rates were shown to be lower in patients with diabetes but were generally similar between treatment groups, with the exception of significantly higher composite cure rates in ASPECT-cUTI for ceftolozane/tazobactam than for levofloxacin in patients without diabetes. Rates of AEs were also significantly higher in patients with diabetes but were comparable between treatment groups. Overall, the results of this subgroup analysis confirm previous findings in the published literature demonstrating that diabetes increases the risk for poor clinical outcomes and mortality from infectious disease [3, 16–19]. We can postulate that the high levels of complications (including renal and cardiac disorders and additional ongoing infections) in the patient subgroup with diabetes are likely to have had a negative impact on treatment outcomes and that higher rates of AEs in patients with diabetes were also likely due to comorbidities.

This analysis has several limitations, including the post hoc nature of the calculations, which prohibited any statistical significance surrounding the conclusions. Given that the population with diabetes was not prespecified but was defined post hoc based on medical history, the results are contingent on the accuracy of the data reporting and could be confounded by overestimation or underestimation of this patient subgroup. Furthermore, the patient population in the ASPECT studies may not be reflective of the variety of patients seen in clinical practice. Finally, it must be noted that the correlations seen between AE rates, complicating factors, and poorer outcomes among patients with diabetes may be confounded by other unmeasured factors.

Conclusions

In this post hoc analysis of two phase 3 studies in patients with cIAI and cUTI, baseline factors associated with diabetes included older age, increased weight, and complicating medical factors. Diabetes was associated with lower cure rates and significantly higher AE rates, likely because of the presence of comorbidities. Despite this, ceftolozane/tazobactam was as effective as comparators in treating cUTI and cIAI in patients with diabetes—a population at increased risk for infections and poor clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Mitchell, PhD, and Sarah Utley, PhD, of ApotheCom, Yardley, PA, USA, who provided medical writing and editorial services on behalf of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Employees of the study sponsor, in collaboration with the authors, were involved in the design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

MWP made substantial contributions to acquisition and analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and drafting and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript for submission. JL made substantial contributions to the study conception and design, acquisition and analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript for submission. JAH made substantial contributions to the analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript for submission. All authors had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the work and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

All authors are employees of Merck, Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. JAH also reports holding stocks in Merck & Co., Inc.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies were conducted in accordance with principles of Good Clinical Practice and were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards and regulatory agencies. All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the studies.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- ASPECT

Assessment of the Safety Profile and Efficacy of Ceftolozane/Tazobactam

- cIAI

Complicated intra-abdominal infections

- cUTI

Complicated urinary tract infections

- IV

Intravenous

- q8d

every 8 h

- TOC

Test-of-cure

Contributor Information

Myra W. Popejoy, Email: myra.popejoy@merck.com

Jianmin Long, Email: jianmin.long@merck.com.

Jennifer A. Huntington, Email: jennifer.huntington@merck.com

References

- 1.Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, Thompson TJ, Barker L, Li Y, et al. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years, United States, 1980-2012. JAMA. 2014;312:1218–1226. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387:1513–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benfield T, Jensen JS, Nordestgaard BG. Influence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia on infectious disease hospitalisation and outcome. Diabetologia. 2007;50:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah BR, Hux JE. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:510–513. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertoni AG, Saydah S, Brancati FL. Diabetes and the risk of infection-related mortality in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1044–1049. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalrymple LS, Go AS. Epidemiology of acute infections among patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1487–1493. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01290308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HE, Gamboa C, Warnock DG, Muntner P. Chronic kidney disease and risk of death from infection. Am J Nephrol. 2011;34:330–336. doi: 10.1159/000330673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhanel GG, Chung P, Adam H, Zelenitsky S, Denisuik A, Schweizer F, et al. Ceftolozane/tazobactam: a novel cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination with activity against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Drugs. 2014;74:31–51. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wooley M, Miller B, Krishna G, Hershberger E, Chandorkar G. Impact of renal function on the pharmacokinetics and safety of ceftolozane-tazobactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2249–2255. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02151-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerbaxa (ceftolozane and tazobactam) [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station; Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corp.; 2015.

- 11.Zerbaxa (ceftolozane and tazobactam) [summary of product characteristics]. Hoddesdon, Hertforshire; Merck Sharpe & Dohme Ltd.; 2016.

- 12.Solomkin J, Hershberger E, Miller B, Popejoy M, Friedland I, Steenbergen J, et al. Ceftolozane/tazobactam plus metronidazole for complicated intra-abdominal infections in an era of multidrug resistance: results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial (ASPECT-cIAI) Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1462–1471. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagenlehner FM, Umeh O, Steenbergen J, Yuan G, Darouiche RO. Ceftolozane-tazobactam compared with levofloxacin in the treatment of complicated urinary-tract infections, including pyelonephritis: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial (ASPECT-cUTI) Lancet. 2015;385:1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miettinen O, Nurminen M. Comparative analysis of two rates. Stat Med. 1985;4:213–226. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casqueiro J, Casqueiro J, Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(suppl 1):S27–S36. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.94253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabe M, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, Wullt B, Çek M, Naber KG, et al. Guidelines on urological infections. 2012. http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2017.

- 17.Tsai C-C, Lee J-J, Liu TP, Ko W-C, Wu C-J, Pan C-F, et al. Effects of age and diabetes mellitus on clinical outcomes in patients with peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2013;14:540–546. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomsen RW, Hundborg HH, Lervang H-H, Johnsen SP, Schønheyder HC, Sørensen HT. Diabetes mellitus as a risk and prognostic factor for community-acquired bacteremia due to enterobacteria: a 10-year, population-based study among adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:628–631. doi: 10.1086/427699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pertel PE, Haverstock D. Risk factors for a poor outcome after therapy for acute pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2006;98:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.