Abstract

Background:

Multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae has been considered as a serious global threat. This study was done to investigate carbapenemase producing genomes among K. pneumoniae isolates in Isfahan, Central Iran.

Materials and Methods:

In a cross-sectional study from 2011 to 2012, 29 carbapenem resistant (according to disc diffusion method) carbapenemase producing (according to modified Hodge test) K. pneumoniae strains were collected from Intensive Care Unit (ICUs) of Al-Zahra referral Hospital. In the strains with the lack of sensitivity to one or several carbapenems, beta-lactams, or beta-lactamases, there has been performed modified Hodge test to investigate carbapenmase and then only strains producing carbapenmases were selected for molecular methods.

Results:

In this study, there have been 29 cases of K. pneumoniae isolated from hospitalized patients in the (ICU). Three cases (10.3%) contained blaVIM, 1 case (3.4%) contained blaIMP, and 1 case (3.4%) contained blaOXA. The genes blaNDM and blaKPC were not detected. Then, 16 cases (55.2%) from positive cases of K. pneumoniae were related to the chip, 4 cases (13.8%) to catheter, 6 cases (20.7%) to urine, and 3 cases (10.3%) to wound.

Conclusion:

It is necessary to monitor the epidemiologic changes of these carbapenemase genes in K. pneumoniae in our Hospital. More attention should be paid to nosocomial infection control measures. Other carbapenemase producing genes should be investigated.

Keywords: Carbapenemase, imipenemas, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, New Delhi metslb-b-lactamase, oxacillinase, Verona integron-encoded metallo-b-lactamase

Introduction

The emergence of carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae is of concern because for which, very few (if any) antibiotic alternatives remain available. This is the reason why early detection of carbapenemase producers is significant.[1] On the other hand, in some cases, despite microbial resistance, there is no increase in minimum inhibitory concentration of carbapenems, and so using molecular techniques and not only phenotypic tests are very helpful to decrease mortality, morbidity, and treatment costs.[2]

Understanding the background of genetic mechanisms information of resistance to antibiotics can facilitate the ways of prevention, control, and limitation of the infectious diseases. This can be easily performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) molecular methods with high reliability. It is necessary to use PCR molecular methods to prove the conclusive existence of carbapenemase genomes. In fact, PCR molecular methods are the standard techniques to identify carbapenemases.[3,4]

According to a study of Poirel et al.[3] in 2011, multiplex PCR methods are as suitable as simplex PCR methods to screen productive genes of carbapenemases, and these methods are considered as the rapid and trustworthy methods (<4 h).

In geographical areas that the carbapenemase producing organisms are not endemic, all dominant genes can produce resistance and it is necessary to consider multiplex PCR methods as the first screening method. Also, this method is suitable in epidemiological studies and is an economical method.[5]

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen from the family Enterobacteriaceae capable to cause carbapenem resistant infections in hospitals especially Intensive Care Units (ICUs). The investigation of the studies has shown that the most common genes producing carbapenemases in K. pneumoniae are derived from five genes K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), imipenemase (IMP), Verona integron-encoded metallo-b-lactamase (VIM), oxacillinase (OXA), and New Delhi metslb-b-lactamase (NDM).[6]

Due to phenotypic methods, there are several reports on the appearance of K. pneumoniae resistant to carbapenems obtained from the patients hospitalized in ICUs in Al-Zahra referral Hospital of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The purpose of this study is to investigate the prevalence of KPC, IMP, VIM, OXA, and NDM genes in K. pneumoniae isolates in Al-Zahra Hospital. Also, due to limited financial resources, there is not possible to investigate other genes in this study.

This study can be helpful in providing initial information on the prevalence of the nosocomial infections by K. pneumoniae producing carbapenemases in order to monitor and control the drug resistances and codify suitable policies for the identification and control of the nosocomial infections and planning principles to physicians and health administrations.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study, conducted in Al-Zahra referral Hospital, Isfahan in 2011–2012. The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Twenty-nine carbapenemase producing K. pneumoniae specimens were collected from the ICUs of Al-Zahra Hospital of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The clinical sources of the specimens included blood, urine, sputum, and wound secretions.

The diagnosis of Klebsiella was performed using the colony morphology. Susceptibility profile was identified by Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method as recommended by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The modified Hodge test also was performed to endorse the existence of carbapenmase enzymes according to CLSI recommendations and only carbapenmases producing strains were selected for molecular methods.

In all samples, DNA was extracted using of phenol-chloroform method and five pair primers blaKPC, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaNDM, and blaOXA with the sizes 232–798 bp and one pair primer blaSHV-1 for the initial control and the confirmation of K. pneumoniae (made by Metabion Company, Germany) was purchased in the form of lyophilization [Table 1]. Amplification was performed using thermocycler T-CY (Netherland). Every cycle includes denaturation DNA at 94°C for 10 min and then other amplification includes 30 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 40 cycles at 52°C for 40 s and 50 cycles at 72°C for 30 s and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. After third stage and final stage of the amplification, the product was stained on an agarose gel (2%), and analyzed with ethidum bromide in voltage 100 for an hour with electrophoresis set (made by Paya Pajoohesh, Pars Company, Iran), and then the multiplied genes were separated due to their molecular weight. Finally, the separated genes were observed and recorded the composed images in the detector and recording gel set (UVI doc). Also, detection of genes was compared with positive control.

Table 1.

The properties of used primers in PCR reaction

Results

In this study, there have been 29 cases of K. pneumoniae isolated from hospitalized patients in the ICU. The mean ages of the patients were 53.6 ± 18.2 in the range of 20–78 years. Among them, 20 patients were male (69%), and 9 patients were female (31%). The mean age of women and men was 50.4 ± 20.2 and 60.6 ± 10.5 years, respectively, and there was no significant difference between the genders (P = 0.17).

As shown in Table 2, the gene expression was shown based on patients age, sex, and source of sample. According to this table, no statistically difference between fore groups based above variables.

Table 2.

Gene expression base on demographic data

The investigation of blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA, and blaNDM genes showed that 5 cases (17.2%) from 29 cases contain one of these genes. Three cases (10.3%) contained blaVIM, 1 case (3.4%) contained blaIMP, and 1 case (3.4%) contained blaOXA (P < 0.05). The genes blaNDM and blaKPC were not detected (P < 0.05) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of genes expression in 29 cases of Klebsiella pneumoniae

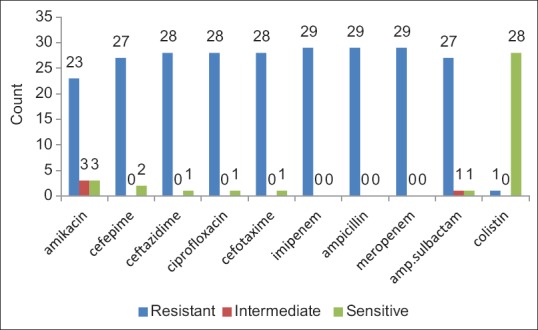

Then, 16 cases (55.2%) from positive cases of K. pneumoniae were related to the chip, 4 cases (13.8%) to catheter, 6 cases (20.7%) to urine, and 3 cases (10.3%) to wound. Due to these results, the greatest resistance was to ampicillin and meropenem compared to imipenem so that each case from 29 cases (100%) were resistant to these antibiotics. Also, 28 samples (6.96%) were resistant to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and cefotaxime and 1 case (3.4%) was susceptible to these three antibiotics. Also, 27 cases (93.1%) were resistant to cefepime, and 23 samples (3.70%) were resistant to amikacin. The only antibiotic affected on these strains effectively was colistin, so that all 29 samples were susceptible to it [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae samples

Discussion

The increasing prevalence of multi-drug resistant K. pneumoniae isolates has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates. The overall purpose of this study is to investigate the prevalence of blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA, and blaNDM genes in K. pneumoniae by multiplex PCR molecular method in isolated specimens from patients admitted in ICUs in Al-Zahra Hospital during 2011–2012.

The blaKPC is the most common carbapenemase in the United States.[7] Several reports described hospital outbreaks in the North-eastern United States involving K. pneumoniae carrying KPC.[8,9] KPC-harboring isolates have also been increasingly recovered from other parts of the world, including Europe,[10] Asia,[11,12] and South America.[13] KPC producing K. pneumoniae isolates have been reported from Tehran, Iran.[14]

The blaNDM has been reported from India, Pakistan, and other parts of Asia, Europe, North America, and Australia.[15,16] In 2013, Shahcheraghi et al., reported first case of NDM-producing K. pneumoniae in Tehran, Iran.[17]

In our study, the blaKPC and blaNDM were not identified so far, because of rapid progression rates of these genes, it is necessary to monitor the epidemiologic changes of these carbapenemase genes in K. pneumonia in our hospital. One study[18] reported high frequency of blaKPC gene in K. pneumonia in Al-Zahra Hospital, but they used nonmolecular methods and genes can only be detected by molecular methods.

The blaVIM and blaIMP genes have been described in Asia, Europe, North America, South America, and Australia.[19,20] According to a study of Zeighami et al. in 2015 in Zanjan, Iran, metallo-b-lactamase producing K. pneumoniae strains carried blaIMP and blaVIM were found in 100% and 41·6%, respectively.[21]

The blaOXA was identified in Turkey, Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa.[22] In 2013, Azimi et al., reported first case of OXA-producing K. pneumoniae in Iran (Azimi).

In our study, blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaOXA were identified in the minority (17.2%) of samples. Thus, other carbapenemase producing genes should be investigated.

It is suggested that further studies with more samples should be considered to investigate the existence of genes containing carbapenemases. By recognition of resistant organisms and prescribing suitable antibiotics, we can decrease the mortality and morbidity of hospitalized patients in ICUs and minimize the costs and duration of hospitalization.

In order to existence of blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaOXA genes in K. pneumoniae in our hospital and possibility of horizontal transmission to other bacteria, more attention should be paid to nosocomial infection control measures.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Poirel L, Pitout JD, Nordmann P. Carbapenemases: Molecular diversity and clinical consequences. Future Microbiol. 2007;2:501–12. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borer A, Saidel-Odes L, Riesenberg K, Eskira S, Peled N, Nativ R, et al. Attributable mortality rate for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:972–6. doi: 10.1086/605922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70:119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuzon G, Ouanich J, Gondret R, Naas T, Nordmann P. Outbreak of OXA-48-positive carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2420–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01452-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel JB, Rasheed JK, Kitchel B. Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae: Activity, epidemiology and laboratory detection. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2009;31:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:165–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Won SY, Munoz-Price LS, Lolans K, Hota B, Weinstein RA, Hayden MK, et al. Emergence and rapid regional spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:532–40. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratu S, Landman D, Haag R, Recco R, Eramo A, Alam M, et al. Rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in New York city: A new threat to our antibiotic armamentarium. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1430–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marquez P, Terashita D, Dassey D, Mascola L. Population-based incidence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae along the continuum of care, Los Angeles county. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:144–50. doi: 10.1086/669087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naas T, Nordmann P, Vedel G, Poyart C. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4423–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4423-4424.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leavitt A, Navon-Venezia S, Chmelnitsky I, Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Emergence of KPC-2 and KPC-3 in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in an Israeli hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3026–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei ZQ, Du XX, Yu YS, Shen P, Chen YG, Li LJ. Plasmid-mediated KPC-2 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:763–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01053-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villegas MV, Lolans K, Correa A, Suarez CJ, Lopez JA, Vallejo M, et al. First detection of the plasmid-mediated class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from South America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2880–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00186-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rastegar Lari A, Azimi L, Rahbar M, Fallah F, Alaghehbandan R. Phenotypic detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase among burns patients: First report from Iran. Burns. 2013;39:174–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidjabat H, Nimmo GR, Walsh TR, Binotto E, Htin A, Hayashi Y, et al. Carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae due to the New Delhi metallo-ß-lactamase. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:481–4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase in two patients – Rhode Island, March 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:446–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahcheraghi F, Nobari S, Rahmati Ghezelgeh F, Nasiri S, Owlia P, Nikbin VS, et al. First report of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;19:30–6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moayednia R, Shokri D, Mobasherizadeh S, Baradaran A, Fatemi SM, Merrikhi A. Frequency assessment of ß-lactamase enzymes in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella isolates in patients with urinary tract infection. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(Suppl 1):S41–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crespo MP, Woodford N, Sinclair A, Kaufmann ME, Turton J, Glover J, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-8, a novel metallo-beta-lactamase, in a tertiary care center in Cali, Colombia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5094–101. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5094-5101.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peleg AY, Franklin C, Bell J, Spelman DW. Emergence of IMP-4 metallo-beta-lactamase in a clinical isolate from Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:699–700. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeighami H, Haghi F, Hajiahmadi F. Molecular characterization of integrons in clinical isolates of betalactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Iran. J Chemother. 2015;27:145–51. doi: 10.1179/1973947814Y.0000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]