Abstract

Infective endocarditis still remains a dreaded illness among treating physicians because of the disease course, its need for meticulous antibiotic management, complications, and overall morbidity. Peripheral mycotic aneurysms are a rarely reported complication of infective endocarditis. Mycotic aneurysms occur in about 5%–10% of cases of infective endocarditis, and most of them involve the intracranial vessels. Here, we report a case of native valve endocarditis in a 74-year-old man caused by Kocuria rosea. He presented with septic shock and acute kidney injury. His illness was complicated by a right popliteal artery mycotic aneurysm. He was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone and vancomycin. The mycotic aneurysm needed aneurysmectomy and anastomosis with a graft.

KEY WORDS: Immunocompetent host, infective endocarditis, Kocuria rosea

Introduction

Kocuria spp. is Gram-positive cocci belonging to the genus micrococci. They are frequent skin commensals. There are reports of invasive infections due to Kocuria in immune compromised hosts. However, the prevalence of Kocuria infections in humans is underestimated because of its close resemblance with coagulase-negative staphylococci. This article is a report of infective endocarditis caused by Kocuria rosea later complicated as mycotic aneurysm of the popliteal artery and its successful treatment.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with background systemic hypertension on angiotensin receptor blocker and bilateral polycystic kidneys had fever and hiccough. He later developed severe dyspnea and persistent fever and hence was brought to our emergency department.

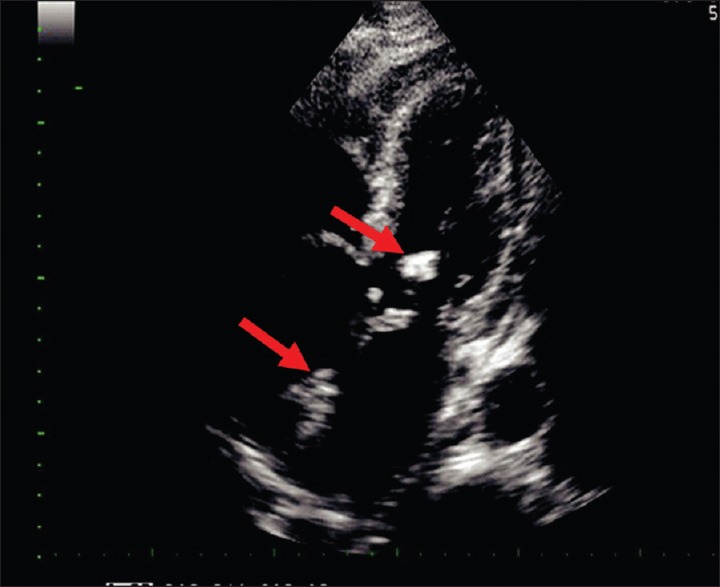

He was brought in with septic shock - he was disoriented, hypotensive blood pressure - 70/42 mmHg, and hypoglycemic with capillary blood glucose of 17 mg/dL on admission. Initial laboratories showed neutrophilic leukocytosis and elevated creatinine. Arterial blood gas showed metabolic acidosis. He was managed with fluid boluses, dextrose, and inotropic agents. His echocardiography identified an echogenic oscillating mass [Figure 1] in the left ventricular outflow and anterior mitral leaflet (aortic and mitral valves). Diagnosis of infective endocarditis with septic shock was made. He continued to require inotropic support and noninvasive ventilation. Empiric antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone and vancomycin was begun.

Figure 1.

Gram-positive cocci in tetrads and cluster seen on colonies grown from the blood

He developed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation early during therapy which was managed with digoxin and amiodarone.

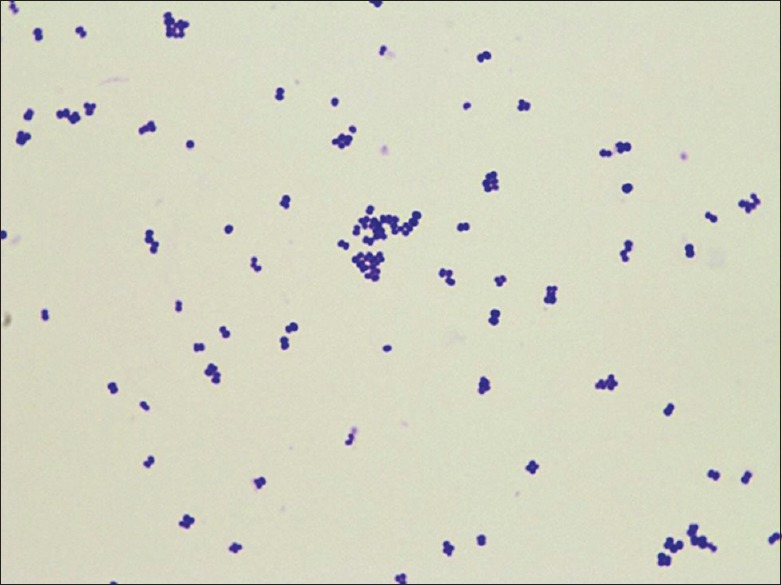

Blood cultures (4 bottles from different sites drawn at the time of admission) were incubated in BacT/ALERT Liquid Media, and the Vitek 2 system (version: 06.01) of 64 tests identified the isolate as pure growth of K. rosea with 95% probability and very good identification confidence in all 4 bottles. ID-GP card was positive for Ala-Phe-Pro-Arylamidase (APPA), alanine arylamidase (AlaA), and tyrosine arylamidase (TyrA). The isolate was then subcultured in sheep blood agar, grew luxuriant pink colonies. Under the microscope, they were Gram-positive cocci in tetrads and clusters [Figure 2]. Subsequent biochemical tests showed that the organism was coagulase negative, bacitracin sensitive, and showed resistance to furazolidone. Subcultures were also subject to antibiotic susceptibility testing. The isolate was sensitive to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, linezolid, penicillin G, tetracycline, and vancomycin. Hence, vancomycin and ceftriaxone were continued. Echocardiography on the 4th day of antimicrobial treatment showed regression in the size of vegetation and improving cardiac contractility (ejection fraction from 55% to 69%). Renal parameters also improved.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic image of the patient showing vegetations (shown with a red arrow) involving the anterior mitral leaflet and the noncoronary cusp of the aortic valve

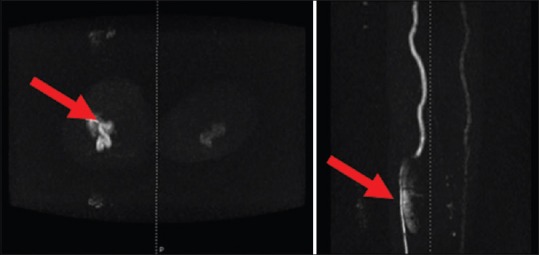

On the 15th day, the patient had pain in the right calf. A venous Doppler ruled out the initial suspicion of deep vein thrombosis. On the next day, a swelling was noted in the calf and popliteal fossa; an arterial Doppler revealed an aneurysmal dilatation of the tibial trunk at the posterior aspect of the calf. Magnetic resonance angiogram of aorta and lower limb arteries showed a large aneurysm in the region of the right tibioperoneal trunk with extensive edema [Figure 3]. As the aneurysm was expanding in spite of directed antimicrobial therapy and considering the risk of rupture, it was decided to intervene surgically. Aneurysmectomy with anastomosis of the popliteal artery to the posterior tibial artery was done using great saphenous vein graft. The patient had an uneventful recovery. Tissue examination showed neutrophilic infiltration with necrotic debris. Microbiological examination confirmed mycotic aneurysm as it also grew K. rosea. Vancomycin (750 mg 8 hourly) was given for 14 days, and ceftriaxone (1 g twice daily) was continued for a total of 4 weeks. The patient was discharged after the antibiotic course. Blood cultures repeated at the end of 1, 4 and 6 weeks were sterile. Follow-up echocardiography showed no vegetations and improvement in cardiac contractility, so valve replacement was not warranted.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance angiogram showing the mycotic aneurysm of the right popliteal artery in both the coronal and axial view (marked with a red pointer)

Literature Review and Discussion

Taxonomy

There are about 300 case reports on Kocuria spp. while there are only a handful of such data about K. rosea. K. rosea first described by Miroslav Kocur, belongs to the group Micrococcus, order Actinomycetales, class Actinobacteria. Seventeen species of Kocuria have been described so far.[1]

Characteristic features and Identification

Kocuria species usually grow on simple media such as sheep blood agar forming luxuriant pink, red, yellow, or cream-colored colonies. Under a microscope, they are Gram-positive cocci found in pairs, tetrads, and clusters. They are obligate aerobes with culture characteristics similar to coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS), hence, phenotype-based identification may fail to identify Kocuria.[1] Despite its limitations, simple tests such as susceptibility to bacitracin and lysozyme and resistance to nitrofurantoin/furazolidone and lysostaphin appear to be very useful in differentiating Kocuria from CoNS.[2]

CoNS being frequently misidentified as Kocuria spp. by the Vitek 2 system have also been reported; hence, Savini et al. recommend routine 16S rRNA gene sequencing on identification of Kocuria to eliminate this confusion.[1]

Epidemiology

Kocuria thrives well in a wide range of temperatures from tropical zones to the ice glaciers of the Himalayas. They were regarded as innocuous nonpathogenic microorganisms and harmless inhabitants of skin, oropharynx, and soil with little clinical relevance. However, there have been a number of recent reports describing the association between Kocuria spp. and infectious diseases. Limited reports of Kocuria infections in the past may probably be attributed to erroneous identification of them as CoNS.[2]

Members of this genus are reported to be opportunistic pathogens. The literature reports a spectrum of cases due to Kocuria causing infective endocarditis, arthritis, central nervous system infections, pneumonia, peritonitis, hepatic abscess, and nosocomial bloodstream infections such as infections associated with indwelling intravenous lines, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis fluids, ventricular shunts, and prosthetic valves in immune-compromised hosts.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9] Whereas, our case with severe intravascular infection in an elderly host with no other risk factor is quite rare.

In most of the cases of catheter-related bacteremia, the possibility of bio-film formation has been postulated. Parallely, removal of the catheter along with antimicrobial therapy was found to be effective and tip cultures grew K. rosea in high counts. This advocates that Kocuria is capable of biofilm formation[4] around indwelling catheters. This concept of ability of biofilm formation is also supported by isolating members of Kocuria species from mat sample of the sea bed in Antarctica and Ice Glaciers of the Indian Himalayas.[1]

Antibiotic susceptibility: apart from the characteristic resistance to nitrofurantoin and furazolidone, Kocuria is susceptible to most of the broad spectrum antibiotics. A report on 219 strains of Kocuria and Micrococcus shows that most strains are sensitive to doxycycline, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, amikacin, and amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, but most are resistant to ampicillin and erythromycin.[2] Takarada et al. describe the presence of efflux pumps that impart multidrug resistance in Kocuria rhizophila, especially to aminoglycoside kanamycin.[2]

Specific antibiotic therapy for Kocuria is yet to be formulated. Various antibiotic regimens with resolution of infection are documented by various authors. Purty et al. report successful treatment with 2 g of vancomycin for 14 days for a case of peritonitis in a patient on CAPD.[4] Gentamycin and Ceftriaxone for 4 weeks were used by Srinivasa et al. for a case of K. rosea endocarditis.[9] Acute cholecystitis due to K. kristinae responded well to levofloxacin 500 mg a day for 14 days.[3] Hence, the duration of treatment depends on the site and type of infection and also removal of in-dwelling catheters if it is the possible source of infection aided in resolution of infection.

Citro et al. describe a case of diabetic foot infection caused by Kocuria complicated as endocarditis with an intracerebral mycotic aneurysm resulting in hemorrhagic stroke.[5] Nearly 2%–10% of patients with infective endocarditis develop mycotic aneurysms, most often involving the intracerebral vessels. Almost 50% of the mycotic aneurysms resolve with antimicrobial therapy. Surgical intervention is needed only in expanding aneurysm with impending rupture or aneurysms that persist even after the completion of the antibiotic course.[7]

While infections due to Kocuria spp. are sparsely reported, Kocuria-associated infective endocarditis complicating with a peripheral mycotic aneurysm is rare and is not reported.

Conclusion

Infections due to Kocuria species are not often reported. This may be attributed to either misidentification by phenotypic assays or emergence of a commensal into a pathogen following rampant use of antibiotics. Now following numerous reports of infections due to Kocuria spp., physicians should not underestimate its prevalence. Although Kocuria infections were reported only in immune-compromised individuals and those with risk factors such as catheters or CAPD, this report of infective endocarditis with peripheral mycotic aneurysm in an elderly individual draws attention to a more ubiquitous emerging microbe pathogen.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Savini V, Catavitello C, Masciarelli G, Astolfi D, Balbinot A, Bianco A, et al. Drug sensitivity and clinical impact of members of the genus Kocuria. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:1395–402. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.021709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takarada H, Sekine M, Kosugi H, Matsuo Y, Fujisawa T, Omata S, et al. Complete genome sequence of the soil actinomycete Kocuria rhizophila. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4139–46. doi: 10.1128/JB.01853-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma ES, Wong CL, Lai KT, Chan EC, Yam WC, Chan AC. Kocuria kristinae infection associated with acute cholecystitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purty S, Saranathan R, Prashanth K, Narayanan K, Asir J, Sheela Devi C, et al. The expanding spectrum of human infections caused by Kocuria species: A case report and literature review. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2013;2:e71. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Citro R, Prota C, Greco L, Mirra M, Masullo A, Silverio A, et al. Kocuria kristinae endocarditis related to diabetic foot infection. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:932–4. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.054536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shashikala S, Kavitha R, Prakash K, Chithra J, Shailaja TS, Shamsul PM. Kocuria varians infective endocarditis. Internet J Microbiol. 2008;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enç Y, Cinar B, Konuralp C, Yavuz SS, Sanïoglu S, Bilgen F. Peripheral mycotic aneurysms in infective endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14:310–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altuntas F, Yildiz O, Eser B, Gündogan K, Sumerkan B, Cetin M. Catheter-related bacteremia due to Kocuria rosea in a patient undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasa KH, Agrawal N, Agarwal A, Manjunath CN. Dancing vegetations: Kocuria rosea endocarditis. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-010339. pii: Bcr2013010339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]