Abstract

Many studies have provided evidence to demonstrate the beneficial renal effects of resveratrol (RESV) due to its antioxidant character and its capacity for activation of surtuin 1. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the protective role of RESV against kidney injury are still incompletely understood. The present study used Lepr db/db (db/db) and Lepr db/m (db/m) mice as models to evaluate the effect of RESV on diabetic nephropathy (DN). RESV reduced proteinuria and attenuated the progress of renal fibrosis in db/db mice. Treatment with RESV markedly attenuated the diabetes-induced changes in renal superoxide dismutase copper/zinc, superoxide dismutase manganese, catalase, and malonydialdehyde as well as the renal expression of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (NOX4), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and E-cadherin in db/db mice. The kidney expression of the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) was increased in db/db mice, but the expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl reductase degradation (HRD1), a ubiquitin E3 ligase, was significantly decreased in the DN model. RESV treatment dramatically decreased IGF-1R and increased HRD1 expressions, consistent with data obtained with HKC-8 cells. HRD1 physically interacted with IGF-1R in HKC-8 cells and liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) data supported the concept that IGF-1R is one of the HRD1 substrates. HRD1 promoted the IGF-1R ubiquitination for degradation in HKC-8 cells, and the down-regulation of HRD1 reversed the protective effects of RESV in HKC-8 cells. In summary, we have demonstrated that RESV reduces proteinuria and attenuates the progression of renal fibrosis in db/db mice. These protective effects of RESV on DN were associated with the up-regulation of HRD1, induced by RESV, and the promotion of IGF-1R ubiquitination and degradation.

Resveratrol (RESV) is a naturally occurring polyphenolic phytoalexin found in many plants and processed plant products, such as grapes, berries, and red wine. RESV has numerous health benefits due to its wide range of bioactivities, including antioxidant, antiinflammatory, cardioprotective, antidiabetic, anticancer, and renal protective effects (1). RESV can ameliorate several types of renal injury in animal models, including diabetic nephropathy, hyperuricemia, drug-induced injury, aldosterone-induced injury, and ischemia-reperfusion injury (2). These beneficial effects are thought to be due to the antioxidant properties of RESV, which can directly scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS). RESV also activates a protein, the silent mating type informing regulation 2-homolog surtuin 1 (SIRT1), which subsequently inhibits TGF-β/phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic (Smad)-2/3 pathways, and this response is also associated with numerous protective effects against renal diseases (3). RESV has been reported to reduce cisplatin-mediated p53 acetylation and to ameliorate kidney injury through inhibition of apoptosis (4). RESV protected adipocytes by increasing forkhead box protein O1/SIRT1-dependent antioxidant defenses (5). RESV also altered the nitric oxide response and increased endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation (6). However, the mechanisms underlying these protective actions of RESV against renal injury remain to be established.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major complication of diabetes and the main reason for end-stage renal disease (7). Hyperglycemia contributes to kidney damage by the promotion of inflammation and oxidative stress, which results in glomerular sclerosis and renal interstitial fibrosis. Oxidative stress is induced by an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses. ROS can induce cell and tissue injuries through lipid peroxidation, activation of transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NFκB), production of peroxynitrite, protein kinase C activation, and induction of apoptosis (8). Oxidative stress also induces the development of epithelial mesenchymal transdifferentiation (EMT) of the renal tubules, which show losses of characteristic epithelial proteins, such as E-cadherin, and the acquisition of characteristic mesenchymal proteins, such as α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and vimentin. EMT plays a key role in the development of renal tubular fibrosis and extracellular matrix synthesis. Previous studies have shown that 30% of fibroblast cells derived from epithelial cells are in the process of renal fibrosis (9).

Many signaling proteins and transcription factors are involved in EMT. TGF-β can promote EMT by regulating many pathways, including Smad as well as MAPK-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathways. The TGF-β/Smad2/3 pathway regulation seems to be essential in pathological fibroses (10). TGF-β also activates the noncanonical signaling pathway involved in the process of EMT. Growth factors, including IGFs and TGF-β synergistically promote the development of EMT (11, 12). IGFs and IGF receptors are both expressed in the kidney and play important roles in maintaining the integrity of the glomeruli (13). Increased expression of IGFs is observed in nephropathy, which is characterized by TGF-β overexpression and renal interstitial fibrosis in diseases including polycystic kidney disease and diabetic nephropathy (14). IGF-1 increases in vitro production of collagen and fibronectin protein in rat mesangial cells, whereas IGF-1 and TGF-β have a synergistic effect on matrix protein accumulation in human mesangial cells (15–17). Some studies have demonstrated an involvement of IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) inhibition in the beneficial roles of RESV on human colon cancer cell proliferation and collagen synthesis in intestinal fibroblasts (18).

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl reductase degradation (HRD1), also called synoviolin, is an endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase that functions by targeting misfolded proteins for degradation in processes such as embryogenesis and rheumatoid arthritis (19, 20). HRD1 has been shown to regulate the ubiquitination and degradation of p53 (21), and our previous study also demonstrated that HRD1 plays an important role in regulation of collagen I maturation in renal fibrosis (22). However, the expression and regulation of HRD1 itself with respect to renal injury or about the specific substrates of HRD1 associated with renal disease are still unclear.

In the present study, db/db mice were used as diabetic model to investigate the protective effect of RESV on diabetic nephropathy and to explore the underlying mechanisms. We hypothesized that RESV ameliorates renal injury in db/db mice by HRD1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of specific target proteins.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, plasmid constructs, and antibodies

RESV, TGF-β, MG-132, HRD1 antibody, and ubiquitin antibody were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies against IGF-1R, α-SMA, phosphorylated (p)-Smad3, Smad3, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERK, and ERK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against TGF-β, E-cadherin, and β-actin were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Enhanced green fluorescent protein-tagged HRD1 lentivirus (Lenti-HRD1) was obtained from GENECHEM. Constructs of N-terminal hemagglutinin-tagged IGF-1R (wild type [WT]), hemagglutinin-tagged IGF-1R C-terminal deletion (dCT) were gifts from Dr Dongming Su (Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China). A QuikChange multisite-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to generate a point mutation of IGF-1R by replacing the lysine K1003 with arginine (K1003R). All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Animals and treatments

Twelve-week-old male Lepr db/db (db/db) and Lepr db/m (db/m) mice in a C57BLKS/J background were acquired from the Laboratory Animal Center of Nanjing Medical University. RESV, dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt, was administered via gavage at 40 mg/kg·d to diabetic db/db mice (DN+RESV, n = 8) for 12 weeks (23). The diabetic db/db group (DN; n = 8) and the nondiabetic db/m control group (CON; n = 8) received only 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt. The mice were placed in individual metabolism cages (Nalgene) with ad libitum access to water and food. Animals were fasted from 6:00 pm to 9:00 am before blood sampling. At the end of week 12, all animals were anesthetized and killed. The kidneys were immediately harvested for protein extraction or histological analyses. Blood glucose levels were monitored with a CONTOUR blood glucose monitoring system (Bayer Healthcare). Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine were determined with an automated biochemical analyzer (7600-DDP-ISE; Hitachi Software Engineering). All animal procedures were conducted in agreement with our institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Oxidative stress parameters

Small fragments of renal cortical tissue were rinsed with 0.15 M NaCl containing 1 mM EDTA, frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen. The tissues were homogenized in an ice bath for 30 seconds with 0.3 M perchloric acid (HClO4) using an UltraTurax homogenizer (Janken Kunkel Ika-Werk). The homogenate was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was neutralized with trioctylamine (0.2 volumes) and trichlorofluoromethane (0.8 volumes) and then used for determination of malonydialdehyde (MDA), after its conjugation to thiobarbituric acid, and for the determination of the antioxidant activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) copper (Cu)/zinc (Zn), SOD manganese (Mn), and catalase.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

With the animals under anesthesia, the kidneys were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The tissues were subsequently embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut and stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Masson's trichrome. For immunohistochemical staining, 4-μm paraffin-embedded sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxidase for 10 minutes and Powerblock (BioGenex Laboratories) for 45 minutes and then incubated with specific primary antibodies against IGF-1R (1:500) and HRD1 (1:500) for 2 hours at 37°C. After washing with PBS, sections were reacted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako) for 45 minutes at room temperature. The diaminobenzidine was added as a chromagen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and viewed with a Carl Zeiss LSM710 microscope equipped with a digital camera.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of protein from kidney tissues or cell lysates were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes. Unbound sites were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk powder in Tris-buffered saline and 0.2% Tween 20 (TBST; 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20. The blots were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-IGF-1R, 1:1000; anti-E-cadherin, 1:1000; anti-α-SMA, 1:3000; anti-TGF-β, 1:1000; anti-p-Smad3, 1:1000; anti-Smad3, 1:1000; anti-p-Akt, 1:500; anti-Akt, 1:500; anti-ERK, 1:800; anti-p-ERK, 1:800; anti-β-actin, 1:5000; antitubulin, 1:5000) at room temperature for 2 hours. The blots were then washed three times for 10 minutes each with TBST and incubated for 1 hour with 2 μg/mL horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in TBST with 5% milk, followed by three TBST washes. The reactive bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and exposed to X-ray film (Eastman Kodak Co). Tubulin expression provided an internal control. Immunoblot data were scanned, and band densities were quantified using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland).

Cell culture and coimmunoprecipitations

Human proximal tubular epithelial cells (clone 8; hereafter, HKC-8) were kindly provided by Dr Elif Erkan (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). The growth medium for HKC-8 cells was composed of DMEM-Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. The concentration of glucose in cell culture medium was 3151 mg/L. HKC-8 cells were typically seeded at approximately 70% confluence in complete medium for 24 hours and then serum starved for 16 hours, followed by incubation with recombinant TGF-β (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours, except as otherwise indicated. The cells were then collected, and cell lysates were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 16 000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and total protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic assay protein assay kit (Pierce). Cell lysates were either coimmunoprecipitated (see below) or analyzed directly by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Coimmunoprecipitations (Co-IPs) were done by incubating 0.5–1.0 mg of total cellular protein with specific antibodies and protein G-agarose in the cold room for 3–5 hours. The beads were then washed four times with Co-IP buffer, and the immunoprecipitated material was eluted from the beads by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and shaking at 95°C for 5 minutes. Immunoprecipitated materials were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as above.

Transient transfections of plasmid constructs and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

HRD1 siRNA and scrambled siRNA were obtained from Dharmacon Inc as SMART-pool reagents. These consist of four SMART selection designed siRNAs targeting four regions of the same mRNA without targeting related gene family members. In vitro transient transfections with plasmids or siRNAs were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), as described previously. In brief, HKC-8 cells grown in six-well plates were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with the indicated plasmids at 4 μg of cDNA/well. For the transfections with HRD1 siRNA, 100 pmol of siRNA was used for 5 × 105 cells in 2 mL of culture medium. After 24 hours, the cells were rinsed with PBS and were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; 1% sodium deoxycholate; and 0.1% SDS). Cell extracts were used for immunoblot analysis.

RNA extraction, purification, and real-time PCR analyses

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol RNA isolation system (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was performed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche) as described previously (24). The mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR using a LightCycler480 II sequence detection system (Roche). Primers used to identify were as follows: HRD1, forward, 5′-AAC CCC TGG GAC AAC AAG G-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCG AGA CAT GATG GCA TCT G-3′; IGF-1R, forward, 5′-GTG GGG GCT CGT GTT TCT C-3′, reverse, 5′-GAT CAC CGT GCA GTT TTC CA-3′; and β-actin as internal control, forward, 5′-GCA AGT GCT TCT AGG CGG AC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAG AAA GGG TGT AAA ACG CAG C-3′.

Immunofluorescence staining

HKC-8 cells were cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated coverslips in a 24-well plate. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature, washed, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes, and blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS at room temperature for 2 hours. Mouse anti-HRD1 (1:200) and rabbit anti-IGF-1R (1:500) staining were done at room temperature for 2 hours, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) was used to mount the coverslips to slides, which were viewed with a Zeiss LSM710 microscope equipped with a digital camera (Carl Zeiss).

Cycloheximide chases

HKC-8 cells were plated and transfected as described above. On the day after transfection, the cell culture medium was changed to the medium containing 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (freshly diluted from a 100 mg/mL stock in dimethylsulfoxide) and 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (freshly diluted from a 10 mg/mL stock in ethanol). The cells were lysed at the indicated time points and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

Mass Spectrometry

HKC-8 cells were infected with or without Lenti-HRD1. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HRD1 antibody. Protein digestion, labeling, mass spectrometry data acquisition, and identification were completed in the analysis center of Nanjing Medical University, as described before (25). In brief, the labeled peptides were analyzed on a LTQ-Orbitrap instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to a Nano ACQUITY UPLC system via a nanospray source. The liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was operated in the positive ion model as described previously. The tandem mass spectrometry spectra acquired from precursor ions were submitted to Maxquant (version 1.2.2.5), and search parameters were followed, as described before (25).

Statistical analysis

Western blot analyses were completed by scanning and analyzing the intensity of hybridization signals using the NIH Image J software program (National Institutes of Health). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software. The data are expressed as mean ± SE. An ANOVA with post hoc comparisons was used to determine the statistical differences among the groups. Significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

Renal protective effects of RESV in db/db mice

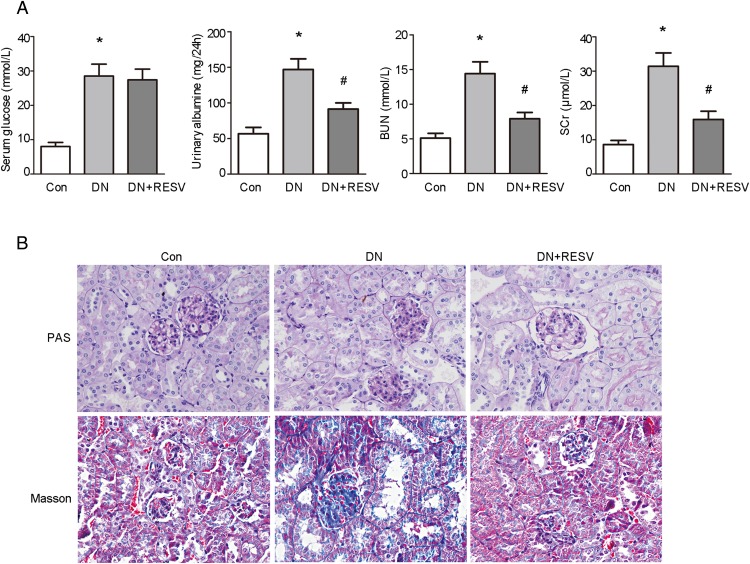

The db/db mice were chosen in the present study because they develop detectable DN (26, 27). Twelve-week-old male db/db mice underwent RESV treatment for 12 weeks, whereas db/m mice served as the nondiabetic controls. As shown in Table 1, body weight and kidney weight were significantly greater in db/db mice than in control mice. RESV treatment significantly improved body weight and kidney weight. As shown in Figure 1A, the db/db mice showed significantly increased fasting serum glucose, but RESV did not affect fasting serum glucose. Overt albuminuria was evident in the db/db mice compared with the control mice. RESV treatment produced a significant reduction in albuminuria. The db/db mice showed significantly increased BUN and serum creatinine (SCr), compared with the control mice. Additions of RESV significantly reduce BUN and SCr in the db/db mice.

Table 1.

Body, Kidney, and Kidney/Body Weight

| Group | n | Start Weight, g | End Weight, g | Kidney Weight, g | Kidney/Body Weight, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 8 | 24.85 ± 2.45 | 28.24 ± 2.67 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.06 |

| DN | 8 | 42.85 ± 3.84a | 54.37 ± 4.78a | 0.27 ± 0.05a | 0.47 ± 0.04 |

| DN+RESV | 8 | 43.67 ± 3.36a | 46.75 ± 4.21a,b | 0.23 ± 0.03a,b | 0.46 ± 0.03 |

P < .05 vs control.

P < .05, vs db/db.

Figure 1. Renal protective effects of RESV in db/db mice.

A, Effects of RESV on serum glucose, albuminuria, and renal function in db/db mice (n = 8 for each group). *, P < .05, compared with control (Con); #, P < .05, compared with DN. B, PAS and Masson's trichrome staining were performed to assess renal the morphological changes of RESV on mice.

PAS and Masson's trichrome staining, performed to assess morphological changes induced by RESV, revealed that db/db mice had marked glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis when compared with the control mice (Figure 1B). RESV treatment significantly reduced glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the db/db mice.

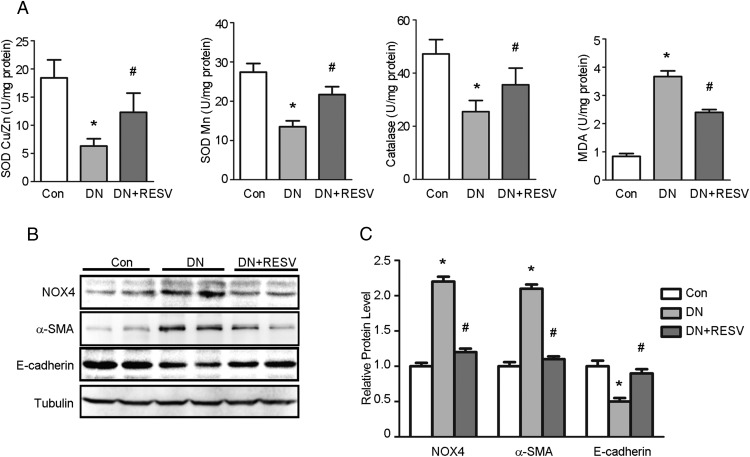

Effects of RESV on renal oxidative stress and EMT markers in db/db mice

We examined the possibility that RESV had antioxidative effects in db/db mice by analyzing the levels of SOD Cu/Zn, SOD Mn, catalase, and MDA in the kidney. As shown in Figure 2A, the db/db mouse kidneys had markedly decreased levels of SOD Cu/Zn, SOD Mn, and catalase, but significantly increased renal levels of MDA, when compared with the control mice. Treatment with RESV markedly attenuated the diabetes-induced changes in renal SOD Cu/Zn, SOD Mn, catalase, and MDA in db/db mice.

Figure 2. Effects of RESV on renal oxidative stress and EMT marker in db/db mice.

A, Treatment of RESV altered the levels of SOD Cu/Zn, SOD Mn, catalase, and MDA in db/db mice (n = 8 for each group). *, P < .05, compared with control (Con); #, P < .05, compared with DN. B, Western blots were performed to determine the expressions of NOX4, α-SMA, and E-cadherin in kidney tissues from different groups. C, Quantitation of immunoblot data for the NOX4, α-SMA, and E-cadherin proteins as in panel B, normalized to β-actin expression. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments, *, P < .05, compared with Con; #, P < .05, compared with DN.

Western blotting revealed that the db/db mice had a marked increase in renal nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (NOX4) expression compared with the control mice, whereas RESV treatment markedly attenuated NOX4 expression in db/db mice (Figure 2B). The effect of RESV on renal tubular EMT in db/db mice was confirmed by examining the expression of the mesenchymal marker, α-SMA, and the epithelial marker, E-cadherin, by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 2B, the db/db mice had a significant increase in α-SMA and a reduction in E-cadherin when compared with control mice. RESV treatment markedly attenuated the changes in α-SMA expression and E-cadherin expression in db/db mice. The mean data for NOX4, α-SMA, and E-cadherin protein expression are shown in Figure 2C.

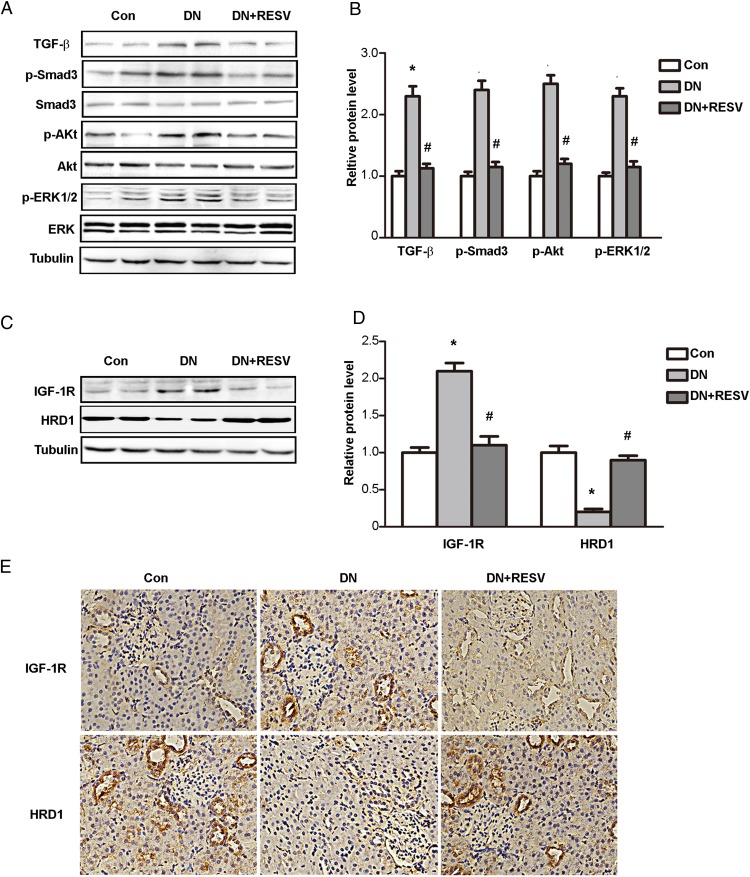

Opposing changes in IGF-1R and HRD1 expression by RESV treatment of db/db mice

We next investigated the potential mechanism of the protective effects of RESV on the kidneys of db/db mice by examining the expression of TGF-β and its downstream molecules by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 3A, a significantly increase occurred in the expression of TGF-β, p-Smad3, p-Akt, and p-ERK in db/db mice compared with the control group, whereas RESV treatment markedly decreased the diabetes-induced increase in TGF-β, p-Smad3, p-Akt, and p-ERK. The mean data for expression of TGF-β and downstream phosphorylated proteins are shown in Figure 3B. These data further confirmed the renal protective role of RESV in diabetic nephropathy.

Figure 3. Opposite expression changes of IGF-1R and HRD1 during treatment of RESV in db/db mice.

A, Western blots were performed to determine the expressions of TGF-β, p-Smad3, Smad3, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERK, and ERK in kidney tissues from different groups. B, Quantitation of immunoblot data for the proteins as in panel A. C, The expressions of IGF-1R and HRD1 were tested using kidney tissues from different groups by Western blot assays. D, Quantitation of immunoblot data for IGF-1R and HRD1 proteins as in panel C. E, Immunohistochemical stainings were performed in kidney tissue of db/db mice treated with or without RESV. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments, *, P < .05, compared with control (Con); #, P < .05, compared with DN.

More interestingly, the kidney expression of IGF-1R was increased in db/db mice, whereas HRD1 expression was significantly decreased in the DN model. RESV treatment dramatically decreased IGF-1R and increased HRD1 expression (Figure 3C). The mean data for IGF-1R and HRD1 protein levels in different groups are shown in Figure 3D. We verified these opposite changes of IGF-1R and HRD1 protein during RESV treatment in db/db mice by immunohistochemical staining of kidney tissues of db/db mice treated with or without RESV. As shown in Figure 3E, IGF-1R and HRD1 were clearly expressed in the tubular epithelium and renal interstitium. IGF-1R expression was significantly increased, whereas HRD1 was decreased in the kidneys of the db/db mice. RESV treatment clearly ameliorated the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1, and these data were consistent with the biochemical data described above. These findings suggested that IGF-1R and HRD1 were related to the protective functions of RESV in DN.

In addition, to further confirm the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1 in the kidney, Western blots were performed to determine the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1 in various kidney cell lines including proximal tubules (NRF-52E and HKC-8 cells) and collecting duct cells (mCCD cells) as well as renal fibroblasts (NRK-49F). Both IGF-1R and HRD1 physically expressed in those renal cells, as shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

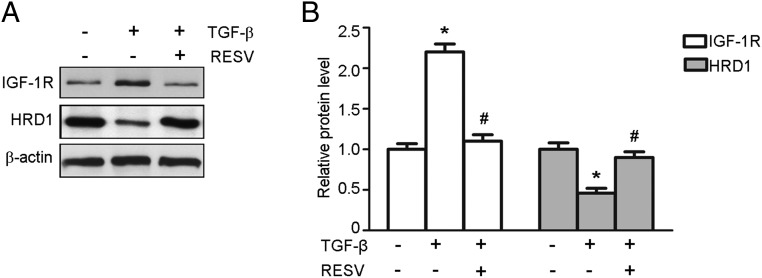

RESV modulates the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1 at the protein and mRNA level

We next determined whether RESV regulated the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1. Considerable evidence indicates that TGF-β is a key mediator in kidney fibrosis associated with the accumulation of the extracellular matrix (28). In our study, TGF-β (10 ng/mL) was used to stimulate HKC-8 cells in the presence or absence of RESV (25 μM) for 24 hours, and then Western blotting and real-time PCR were performed to assess the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1. As shown in Figure 4A, application of RESV decreased the IGF-1R expression but increased the HRD1 expression in the HKC-8 cells. The mean data of IGF-1R and HRD1 protein expression are shown in Figure 4B. These results agree qualitatively with the evaluation of expression at the RNA level (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4. RESV modulates the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1 in HKC-8 cells.

A, TGF-β (10 ng/mL) was used to stimulate HKC-8 cells for 24 hours. Western blot were performed to examine the expression of IGF-1R and HRD1 in HKC-8 cells treated with or without RESV. B, Quantitation of immunoblot data for IGF-1R and HRD1 proteins as in panel A. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments. *, P < .05, compared with control; #, P < .05, compared with DN.

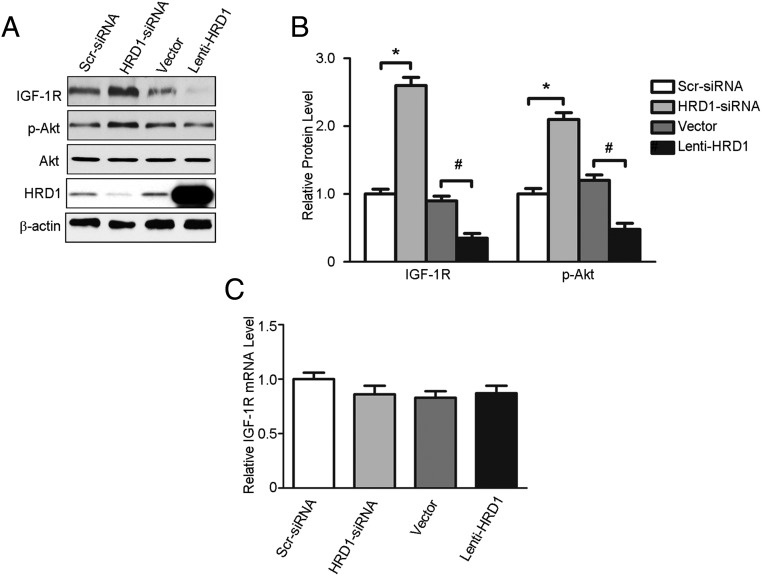

HRD1 regulates the level of IGF-1R expression

The results from the experiments in the previous two sections, in whole animals and HKC-8 cells, suggested opposite effects on IGF-1R and HRD1 expression. The physiological significance between HRD1 and IGF-1R was therefore evaluated in knockdown experiments in HKC-8 cells performed with siRNA targeting HRD1 expression as well as HRD1 overexpression by Lenti-HRD1 infection. HRD1-specific siRNA increased IGF-1R expression levels and the phosphorylation of its downstream target Akt, whereas the overexpression of HRD1 in HKC-8 cells inhibited IGF-1R expression at the protein level and Akt phosphorylation (Figure 5A). The mean data of IGF-1R protein expression after the HRD1 knockdown or overexpression are shown in Figure 5B. In contrast, the down-regulation or up-regulation of HRD1 expression had no effect on IGF-1R mRNA levels (Figure 5C). These data indicated that the regulation of IGF-1R expression by HRD1 occurred at the posttranslational level.

Figure 5. HRD1 regulates the level of IGF-1R expression.

A, Western blots were performed to determine the protein levels of IGF-1R, p-Akt, and HRD1 in HKC-8 cells transfected with HRD1 siRNA, Lenti-HRD1, and their respective control. B, Quantitation of immunoblot data for IGF-1R and p-Akt proteins as in panel A. C, Total mRNA was prepared from HKC-8 cells transfected with HRD1 siRNA, Lenti-HRD1, and their respective controls. IGF-1R mRNA levels were quantified using real-time RT-PCR. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments. *, P < .05, compared with control; #, P < .05, compared with DN.

HRD1 physically interacts with C terminus of IGF-1R

HRD1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, usually acts by a specific interaction with its substrate and then sends the target protein for degradation. We explored the binding proteins of HRD1 by overexpressing Lenti-HRD1 in HKC-8 cells. As shown in Table 2, when the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HRD1 antibody, LC-MS/MS analysis identified 54 peptides that were deemed candidate substrates of HRD1 for ubiquitination. IGF-1R was in the top five of the candidate proteins that were more sensitive as a substrate of HRD1.

Table 2.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of HRD1 Affinity-Purified Complexes

| Gene | Protein | CT TSCa | HRD1 TSCb | Ratio (b to a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SACM1L | Phosphatidylinositide phosphatase SAC1 (fragment) | − | + | |

| PRSS3 | Trypsin-3 | − | + | |

| TPH2 | Tryptophan 5-hydroxylase 2 | − | + | |

| SUDS3 | Sin3 histone deacetylase corepressor complex component SDS3 | − | + | |

| IGF1R | IGF-1 receptor | − | + | |

| PPP1R3B | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3B | − | + | |

| EIF2S2 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 2 | − | + | |

| CDH5 | Cadherin-5 (fragment) | − | + | |

| CAMK4 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV | − | + | |

| DPPA4 | Developmental pluripotency-associated protein 4 | − | + | |

| AIM2 | Interferon-inducible protein AIM2 (fragment) | − | + | |

| CSNK1A1 | Casein kinase I isoform-α | − | + | |

| ISCU | ICSU | − | + | |

| DNAJC28 | DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 28 | − | + | |

| PRKRA | Interferon-inducible double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase activator A | − | + | |

| RYR1 | Ryanodine receptor 1 | − | + | |

| TRMT10C | Mitochondrial ribonuclease P protein 1 | − | + | |

| CEP170 | Centrosomal protein of 170 kDa | − | + | |

| BAIAP2 | Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1-associated protein 2 (fragment) | − | + | |

| ZC3H12B | Probable ribonuclease ZC3H12B | − | + | |

| RPL3 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | − | + | |

| TRIM73 | Tripartite motif-containing protein 73 | − | + | |

| IGHG3 | Ig γ-3 chain C region | − | + | |

| RPL17 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 | − | + | |

| PSTPIP1 | Proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 1 | − | + | |

| SYVN1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase synoviolin | + | + | 1066.69 |

| AP1M1 | AP-1 complex subunit μ-1 (fragment) | + | + | 140.91 |

| HBA1 | Hemoglobin subunit-α | + | + | 12.56 |

| FHL2 | Four and a half LIM domains protein 2 | + | + | 6.79 |

| HSPA1A | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A/1B | + | + | 2.36 |

| PSMA6 | Proteasome subunit-α type-6 | + | + | 2.32 |

| ALB | Serum albumin | + | + | 1.97 |

| ANKFY1 | Ankyrin repeat and FYVE domain-containing protein 1 | + | + | 1.85 |

| HBD | Hemoglobin subunit-δ | + | + | 1.74 |

| RPL32 | 60S ribosomal protein L32 | + | + | 1.59 |

| LDHB | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain | + | + | 1.57 |

| ATRX | Transcriptional regulator ATRX | + | + | 1.42 |

| ACTB | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | + | + | 1.27 |

| HSPA9 | Stress-70 protein, mitochondrial | + | + | 1.19 |

| PFKL | 6-Phosphofructokinase, liver type | + | + | 1.13 |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein | + | + | 1.01 |

| PFKM | 6-phosphofructokinase, muscle type | + | + | 0.94 |

| PFKP | 6-Phosphofructokinase type C | + | + | 0.93 |

| RPLP2 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 | + | + | 0.85 |

| PACSIN2 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons protein 2 | + | + | 0.69 |

| HSPA5 | 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein | + | + | 0.66 |

| ACSS2 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase, cytoplasmic | + | + | 0.61 |

| S100A9 | Protein S100-A9 | + | + | 0.56 |

| SPDL1 | Protein spindly | + | + | 0.56 |

| DCD | Dermcidin | + | + | 0.43 |

| VPS13A | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 13A | + | + | 0.39 |

| HAND2 | Heart- and neural crest derivative-expressed protein 2 (fragment) | + | + | 0.35 |

| DDX39B | HCG2005638, isoform CRA c | + | + | 0.006 |

| KIF14 | Kinesin-like protein KIF14 | + | + | 0.002 |

Abbreviation: CT, Control; TSC, total spectral counts.

HKC-8 cells infected with an empty lentivirus, not expressing HRD1.

HKC-8 cells infected with a lentivirus targeting HRD1.

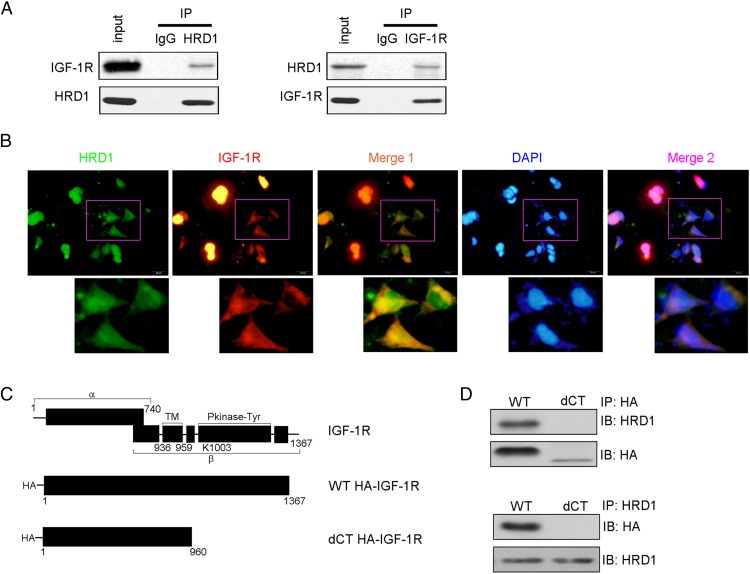

A physical interaction between HRD1 and IGF-1R was detected in the Co-IP analysis in endogenous settings (Figure 6A). We further verified the interaction of IGF-1R and HRD1 in HKC-8 cells by immunofluorescence staining using mouse anti-HRD1 and rabbit anti-IGF-1R antibodies. As shown in Figure 6B, the expressions of HRD1 and IGF-1R were endogenous and intracytoplasmic. Merged images showed a significant colocalization, which was consistent with the biochemical data described in Figure 6A. To investigate the HRD1-specific binding domain of IGF-1R, we constructed IGF-1R deletion mutants (Figure 6C). Co-IPs were performed to detect the interaction between HRD1- and IGF-1R-expressed proteins. Consistent with Figure 6A, there was binding of HRD1 with WT IGF-1R. However, the deletion of the last 407 amino acids from the IGF-1R C terminus (dCT) did not markedly interact with HRD1 (Figure 6D), suggesting that the C-termini of IGF-1R contains the binding site(s) for HRD1.

Figure 6. HRD1 physically interacts with the C terminus of IGF-1R.

A, A physical interaction between HRD1 and IGF-1R was detected in the Co-IP analysis in endogenous settings. IgG was used as a negative control for immunoprecipitation. B, Immunofluorescence staining was performed to verify the interaction of IGF-1R and HRD1 in HKC-8 cells. C, Schematic diagram of WT IGF-1R and the C-terminal IGF-1R deletion constructs. D, The deletion of IGF-1R C-terminus (dCT) did not markedly interacted with HRD1 in HKC-8 cells. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole; HA, hemagglutinin; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

To confirm the proteins identified by LC-MS/MS in Table 2 associated with HRD1, eukaryotic initiation factor 2β and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 4 were detected for their interactions with HRD1 in HKC-8 cells, respectively, using Co-IP techniques (Supplemental Figure 3).

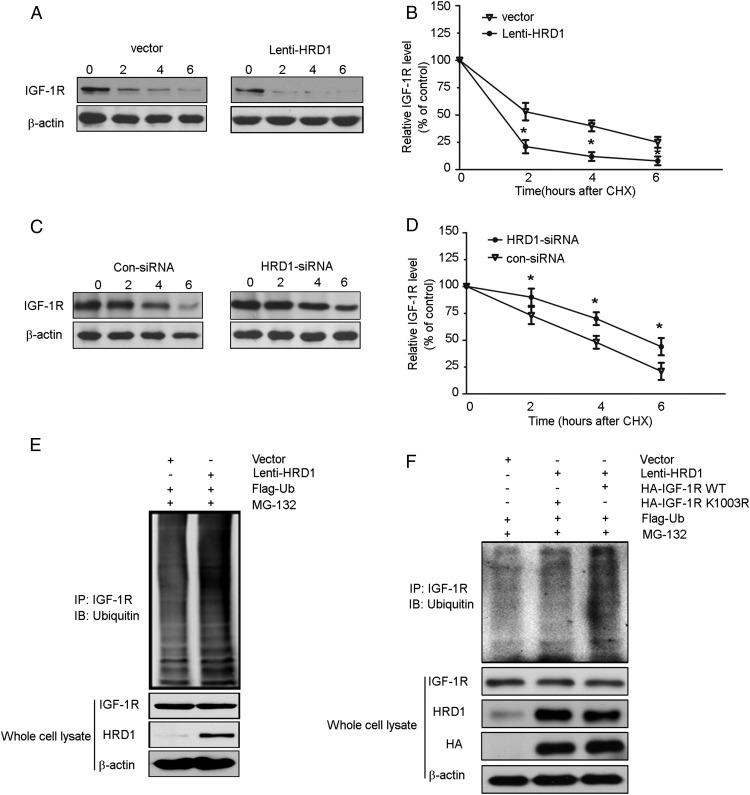

HRD1 promotes IGF-1R ubiquitylation for degradation

The data presented so far implied the model that HRD1 promotes IGF-1R degradation by increasing its ubiquitylation. We hypothesize the steady-state levels of IGF-1R should be in a shorter half-life when HRD1 is overexpressed, and things will be opposed with HRD1 knocking down. Therefore, we first infected HKC-8 cells with or without Lenti-HRD1. The next day, cells were treated with cycloheximide and brefeldin A for 0, 2, 4, or 6 hours to block both the synthesis of new polypeptides and maturation. In agreement with our model, the results showed that IGF-1R disappeared from cells at a much faster rate when HRD1 was overexpressed (Figure 7A). After a 2-hour chase, cells overexpressing HRD1 contained an average of only 25% of the initial amount of IGF-1R, whereas 60% was still present under the basal condition (Figure 7B). In contrast, HRD1 knockdown by its siRNA induced a longer half-life of IGF-1R: at the 4-hour chase, an average of 50% of the initial amount of IGF-1R remained in the HKC-8 cells under the basal condition, but 75% remained in the cells transfected with HRD1 siRNA (Figure 7, C and D). Analysis of the effects of overexpression of HRD1 on IGF-1R ubiquitination, as shown in Figure 7E, revealed that more than twice as much ubiquitin was conjugated to IGF-1R in cells infected with Lenti-HRD1 compared with cells transfected with vector only.

Figure 7. HRD1 promotes IGF-1R ubiquitylation for degradation.

A, A cycloheximide chase was performed to determine IGF-1R biogenesis. The HKC-8 cells were infected with or without Lenti-HRD1 for 24 hours, and then the cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 50 mg/mL) for 0, 2, 4, or 6 hours. The expression of IGF-1R in whole-cell lysates was measured by Western blots. B, The intensity of the IGF-1R protein bands was analyzed by densitometry as in panel A, after normalization to the corresponding β-actin level. C, The HKC-8 cells were transfected with HRD1 siRNA or Con-siRNA and then followed with CHX chase assay. D, The intensity of the IGF-1R protein bands was analyzed by densitometry as in panel C, after normalization to the corresponding β-actin level. E, Flag-ubiquitin was coexpressed in HKC-8 cells with Lenti-HRD1 or vector control with treatment of MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours. Ubiquitinated IGF-1R protein was immunoprecipitated using IGF-1R antibody and further detected with ubiquitin antibody. F, K1003R mutation of IGF-1R decreased its ubiquitylation by HRD1 in HKC-8 cells. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments. *, P < .05, compared with Con. Con, control; HA, hemagglutinin; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Next, to investigate the ubiquitination site of IGF-1R by HRD1, we generated a point mutation (K1003R) and transfected it into HKC-8 cells. As shown in Figure 7F, ubiquitination was abolished in HKC-8 cells with IGF-1R K1003R transfection compared with WT, which suggested K1003 was a ubiquitination site in the C terminal of IGF-1R by HRD1 in HKC-8 cells.

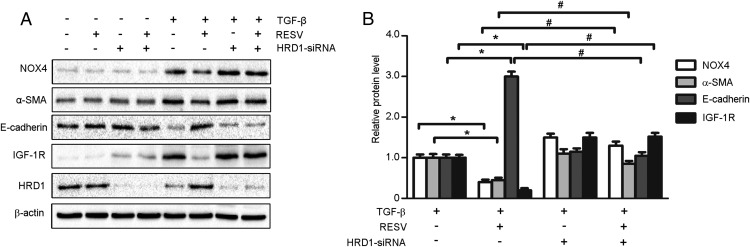

Down-regulation of HRD1 reverses the protective effects of RESV in HKC-8 cells

We validated that IGF-1R ubiquitination by HRD1 was involved in the renal protective role of RESV. HKC-8 cells induced by TGF-β (10 ng/mL) were treated in the presence or absence of RESV (25 μM) or transfected with or without HRD1 siRNA for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 8, TGF-β markedly increased the expression of NOX4 (oxidative stress marker) and α-SMA (mesenchymal marker) but decreased the level of E-cadherin (epithelial marker) expression. Addition of RESV suppressed the increase of NOX4 and α-SMA expression induced by TGF-β and attenuated the decrease of E-cadherin. However, HRD1 knockdown elevated IGF-1R expression and prevented the RESV-induced changes in NOX4, α-SMA, and E-cadherin proteins (Figure 8A). The mean data of NOX4, α-SMA, E-cadherin, and IGF-1R expression with TGF-β treatment in HKC-8 cells are shown in Figure 8B.

Figure 8. Down-regulation of HRD1 reverses the protective effects of RESV in HKC-8 cells induced by TGF-β.

A, Under the basal and TGF-β-stimulated condition, HKC-8 cells were treated with or without RESV, combined with knockdown of HRD1. Western blots were performed to examine the expression of NOX4, α-SMA, E-cadherin, IGF-1R, and HRD1. B, Quantitation of immunoblot data for the NOX4, α-SMA, E-cadherin, and IGF-1R proteins as in panel A, normalized to β-actin expression. Bars are means ± SE from four independent experiments, *, P < .05, compared with TGF-β treatment alone; #, P < .05, compared with TGF-β treatment with RESV.

Discussion

Numerous beneficial pharmacological effects have been reported for RESV, including antioxidative, antiinflammatory, cardioprotective, antidiabetic, antitumor, chemopreventive, neuroprotective, and renal-protective properties (2). However, although many studies have suggested potential pathways with possible involvement in RESV bioprotective effects, the precise molecular mechanisms are still unknown.

Oxidative stress plays a central role in the development of diabetic nephropathy (29, 30). Hyperglycemia increases mitochondrial ROS, which is secondary to the up-regulation of certain NOX subunits that induce progression of diabetic kidney disease (31). ROS induce cell and tissue injuries, which cause the loss of podocytes and increase proteinuria in db/db mice (32, 33). Our results in the present study showed that the kidneys of db/db mice had clearly decreased levels of SOD Cu/Zn, SOD Mn, and catalase, and significantly increased levels of renal MDA, when compared with control mice. The db/db mice also had a marked increase in renal NOX4 expression compared with the control mice. These results were consistent with other previous reports (27, 34, 35). Our findings suggested that the RESV amelioration of the progression of DN was potentially related to its inhibitory activity on oxidative stress in db/db mice and its protection of podocytes.

EMT plays an important role in the development and progression of DN (26). Human renal biopsies from diseased kidneys showed a correlation between the proportion of cells undergoing EMT and both the level of serum creatinine and the degree of interstitial fibrosis (36, 37). In the present study, the db/db mice had a significant reduction in E-cadherin and an increase in α-SMA when compared with the control mice. RESV markedly attenuated these changes in E-cadherin and α-SMA expression in db/db mice. EMT occurs in response to hypoxia, ROS, advanced glycation end products, and numerous profibrotic cytokines, growth factors, and metalloproteinases (38). Much evidence has demonstrated that TGF-β/Smad3 promotes EMT in diabetic nephropathy (11, 39, 40). Our study data suggested that db/db mice had a marked increase in renal TGF-β expression and increased phosphorylation of Smad3 compared with db/m mice. RESV treatment markedly relieved the diabetes-induced increase in renal TGF-β expression and the phosphorylation of Smad3.

We also found that RESV treatment appeared to decrease IGF-1R production, but it increased HRD1 expression, both in vivo and in vitro. Other studies have shown that RESV suppresses colon cancer cell proliferation by the inhibition of the IGF-1R/Wnt signaling pathway and activation of p53 (18). In addition, the down-regulation of collagen I synthesis by RESV was related to the RESV inhibition of IGF-1R and the activation of SIRT1 (41). In the present study, we found RESV had effects on the expression of HRD1 and IGF-1R at both the protein and mRNA levels, but HRD1 regulated IGF-1R expression at posttranslational levels. Therefore, we proposed that there were multiple mechanisms for RESV to participate in renal protection. In this study, we focus on the benefit of HRD1-meditated IGF-1R degradation by RESV treatment in diabetic nephropathy, and our results demonstrated for the first time that a renal-protective response to RESV was associated with IGF-1R ubiquitination and degradation mediated by the E3 ligase, HRD1.

Ubiquitination is a multistep enzymatic reaction involving a sequential process with three enzymes: ATP-dependent single ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin conjugating enzymes (E2), and substrate-ubiquitin E3 ligases. The protein ubiquitination starts with the activation of ubiquitin by a single E1. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to E2, which acts as an ubiquitin carrier protein to form a thioester bond at the E2-ubiquitin (E2-Ub) complex. Subsequently, one of multiple special E3 ligases recruits the substrate and transfers activated ubiquitin linked to the target for the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of the target protein (42).

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) plays important roles in modulation of cellular and protein functions, such as membrane protein trafficking, the cell cycle, and DNA repair. Studies have demonstrated that ubiquitination and degradation of the target protein are involved in renal diseases including DN (43). For example, when various inflammatory cytokines were activated during DN, inhibitory-κB, a protein suppressed by NFκB, was degraded by the UPS, and this allowed the nuclear translocation of NFκB for participation in gene transcription (44). Some studies have reported that the activation of other key signaling pathways related to renal fibrosis, including TGF-β, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and MAPK, were associated with the degradation of some negative signaling proteins through the UPS. TGF-β activation was due to the degradation of negative protein Smad7 by its ubiquitylation (45). In contrast, the degradation of some proteins would be beneficial in renal disease. In our study, we identified that the IGF-1R ubiquitination and degradation mediated by HRD1 was related to the RESV renal protective effect. Regarding the UPS, each E3 ligase is thought to interact with a specific ubiquitin-protein. Our data from LC-MS/MS provided potential binding substrates for HRD1 in HKC-8 cells, and IGF-1R was one of them. Future studies on the functions of these substrates might reveal new mechanisms of DN and DN therapy.

In summary, we have demonstrated the ability of RESV to reduce proteinuria and attenuate the progression of renal fibrosis in db/db mice. These protective effects of RESV on DN were associated with the up-regulation of HRD1, induced by RESV, and the promotion of IGF-1R ubiquitination and degradation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Yongjian Liu (Nanjing Medical University) for the critical suggestions and the proofreading of this manuscript.

Contributions of the authors included the following: C.Y., W.X., and X.L. designed and performed the studies. Y.H., M.L., H.Y., and Y.S. participated in the data collection and analysis. W.X. and X.L. prepared the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31271263 and 81470040 (to X.L.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31271263 and 81470040 (to X.L.).

Footnotes

- BUN

- blood urea nitrogen

- Co-IP

- coimmunoprecipitation

- Cu

- copper

- dCT

- C-terminal deletion

- DN

- diabetic nephropathy

- EMT

- epithelial mesenchymal transdifferentiation

- HKC-8

- human proximal tubular epithelial cells (clone 8)

- HRD1

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl reductase degradation

- IGF-1R

- IGF-1 receptor

- LC-MS/MS

- liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry

- Lenti-HRD1

- HRD1 lentivirus

- MDA

- malonydialdehyde

- Mn

- manganese

- NFκB

- nuclear factor-κB

- NOX4

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4

- p

- phosphorylated

- PAS

- periodic acid-Schiff

- RESV

- resveratrol

- ROS

- reactive oxygen series

- SCr

- serum creatinine

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- SIRT1

- surtuin 1

- α-SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin

- Smad

- phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- TBST

- Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20

- UPS

- ubiquitin-proteasome system

- WT

- wild type

- Zn

- zinc.

References

- 1. Albertoni G, Schor N. Resveratrol plays important role in protective mechanisms in renal disease–mini-review. J Brasil Nefrol. 2015;37:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kitada M, Koya D. Renal protective effects of resveratrol. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:568093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wen D, Huang X, Zhang M, et al. Resveratrol attenuates diabetic nephropathy via modulating angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim DH, Jung YJ, Lee JE, et al. SIRT1 activation by resveratrol ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal injury through deacetylation of p53. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F427–F435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Subauste AR, Burant CF. Role of FoxO1 in FFA-induced oxidative stress in adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E159–E164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Naderali EK, Doyle PJ, Williams G. Resveratrol induces vasorelaxation of mesenteric and uterine arteries from female guinea-pigs. Clin Sci (London, Engl). 2000;98:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ghaderian SB, Hayati F, Shayanpour S, Beladi Mousavi SS. Diabetes and end-stage renal disease; a review article on new concepts. J Renal Injury Prevent. 2015;4:28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ha H, Hwang IA, Park JH, Lee HB. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2008;82(suppl 1):S42–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roberts AB, Tian F, Byfield SD, et al. Smad3 is key to TGF-β-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, fibrosis, tumor suppression and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hills CE, Squires PE. The role of TGF-β and epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, et al. IGF-1R/epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) cross talk suppresses the erlotinib-sensitizing effect of EGFR exon 19 deletion mutations. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bridgewater DJ, Dionne JM, Butt MJ, Pin CL, Matsell DG. The role of the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) in glomerular integrity. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2008;18:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bridgewater DJ, Ho J, Sauro V, Matsell DG. Insulin-like growth factors inhibit podocyte apoptosis through the PI3 kinase pathway. Kidney Intl. 2005;67:1308–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pricci F, Pugliese G, Romano G, et al. Insulin-like growth factors I and II stimulate extracellular matrix production in human glomerular mesangial cells. Comparison with transforming growth factor-β. Endocrinology. 1996;137:879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schreiber BD, Hughes ML, Groggel GC. Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates production of mesangial cell matrix components. Clin Nephrol. 1995;43:368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamaroglio TA, Lo CS. Regulation of fibronectin by insulin-like growth factor-I in cultured rat thoracic aortic smooth muscle cells and glomerular mesangial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1994;215:338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vanamala J, Reddivari L, Radhakrishnan S, Tarver C. Resveratrol suppresses IGF-1 induced human colon cancer cell proliferation and elevates apoptosis via suppression of IGF-1R/Wnt and activation of p53 signaling pathways. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amano T, Yamasaki S, Yagishita N, et al. Synoviolin/Hrd1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a novel pathogenic factor for arthropathy. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2436–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gao B, Calhoun K, Fang D. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α induce the expression of Synoviolin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, in mouse synovial fibroblasts via the Erk1/2-ETS1 pathway. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamasaki S, Yagishita N, Sasaki T, et al. Cytoplasmic destruction of p53 by the endoplasmic reticulum-resident ubiquitin ligase 'Synoviolin.' EMBO J. 2007;26:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li L, Shen Y, Ding Y, Liu Y, Su D, Liang X. Hrd1 participates in the regulation of collagen I synthesis in renal fibrosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;386:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, et al. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Meta. 2008;8:157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liang X, Peters KW, Butterworth MB, Frizzell RA. 14–3-3 isoforms are induced by aldosterone and participate in its regulation of epithelial sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16323–16332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang F, Shi Z, Wang P, You W, Liang G. Comparative proteome profile of human placenta from normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Y. New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:212–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, et al. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature. 2000;404:787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meng XM, Tang PM, Li J, Lan HY. TGF-β/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol. 2015;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sedeek M, Nasrallah R, Touyz RM, Hebert RL. NADPH oxidases, reactive oxygen species, and the kidney: friend and foe. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1512–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lindblom R, Higgins G, Coughlan M, de Haan JB. Targeting mitochondria and reactive oxygen species-driven pathogenesis in diabetic nephropathy. Rev Diabet Stud. 2015;12:134–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thallas-Bonke V, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Cooper ME. Nox-4 and progressive kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sato-Horiguchi C, Ogawa D, Wada J, et al. Telmisartan attenuates diabetic nephropathy by suppressing oxidative stress in db/db mice. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2012;121:e97–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou G, Wang Y, He P, Li D. Probucol inhibited Nox2 expression and attenuated podocyte injury in type 2 diabetic nephropathy of db/db mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36:1883–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haidara MA, Mikhailidis DP, Rateb MA, et al. Evaluation of the effect of oxidative stress and vitamin E supplementation on renal function in rats with streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2009;23:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palm F, Cederberg J, Hansell P, Liss P, Carlsson PO. Reactive oxygen species cause diabetes-induced decrease in renal oxygen tension. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ng YY, Huang TP, Yang WC, et al. Tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int. 1998;54:864–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rastaldi MP, Ferrario F, Giardino L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tubular epithelial cells in human renal biopsies. Kidney Int. 2002;62:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burns WC, Twigg SM, Forbes JM, et al. Connective tissue growth factor plays an important role in advanced glycation end product-induced tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: implications for diabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2484–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rhyu DY, Yang Y, Ha H, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in TGF-β1-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang B, Jha JC, Hagiwara S, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1-mediated renal fibrosis is dependent on the regulation of transforming growth factor receptor 1 expression by let-7b. Kidney Int. 2014;85:352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li P, Liang ML, Zhu Y, et al. Resveratrol inhibits collagen I synthesis by suppressing IGF-1R activation in intestinal fibroblasts. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4648–4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahner A, Gong X, Frizzell RA. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator degradation: cross-talk between the ubiquitylation and SUMOylation pathways. FEBS J. 2013;280:4430–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gao C, Huang W, Kanasaki K, Xu Y. The role of ubiquitination and sumoylation in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:160692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wertz IE, Dixit VM. Signaling to NF-κB: regulation by ubiquitination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gao C, Aqie K, Zhu J, et al. MG132 ameliorates kidney lesions by inhibiting the degradation of Smad7 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:918396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]