Abstract

Stable somatostatin analogues and dopamine receptor agonists are the mainstay for the pharmacological treatment of functional pituitary adenomas; however, only a few cellular assays have been developed to detect receptor activation of novel compounds without disrupting cells to obtain the second messenger content. Here, we adapted a novel fluorescence-based membrane potential assay to characterize receptor signaling in a time-dependent manner. This minimally invasive technique provides a robust and reliable read-out for ligand-induced receptor activation in permanent and primary pituitary cells. The mouse corticotropic cell line AtT-20 endogenously expresses both the somatostatin receptors 2 (sst2) and 5 (sst5). Exposure of wild-type AtT-20 cells to the sst2- and sst5-selective agonists BIM-23120 and BIM-23268, respectively, promoted a pertussis toxin- and tertiapin-Q-sensitive reduction in fluorescent signal intensity, which is indicative of activation of G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels. After heterologous expression, sst1, sst3, and sst4 receptors also coupled to GIRK channels in AtT-20 cells. Similar activation of GIRK channels by dopamine required overexpression of dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs). Interestingly, the presence of D2Rs in AtT-20 cells strongly facilitated GIRK channel activation elicited by the sst2-D2 chimeric ligand BIM-23A760, suggesting a synergistic action of sst2 and D2Rs. Furthermore, stable somatostatin analogues produced strong responses in primary pituitary cultures from wild-type mice; however, in cultures from sst2 receptor-deficient mice, only pasireotide and somatoprim, but not octreotide, induced a reduction in fluorescent signal intensity, suggesting that octreotide mediates its pharmacological action primarily via the sst2 receptor.

The expression of somatostatin receptors (ssts) and dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) provides the rational basis for pharmacological therapy of pituitary tumors (1). Somatostatin analogues (SSAs) and dopamine receptor agonists act synergistically to control excessive hormonal secretion from functional pituitary tumors (2). The ssts and D2R exert their functions via the same transduction systems. In fact, these receptors share many Gi protein-mediated downstream signaling effects, such as inhibition of adenylate cyclase (3–5), stimulation of phosphotyrosine phosphatase (6, 7), inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels (8, 9), and activation of G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels (10–13). Both somatostatin (SS-14) and dopamine are neurohormones implicated in the negative control of hormonal secretion from the anterior pituitary (14, 15), and these hormones function via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). SS-14 exerts its antisecretory effects via 5 different sst subtypes, termed sst1–sst5. Four of the 5 sst subtypes, namely sst1, sst2, sst3, and sst5, as well as D2R, are expressed in the normal pituitary (16–19). Coexpression of sst2, sst5, and D2R is observed in many growth hormone (GH)-producing adenomas (20, 21), suggesting the convenience of a targeted combination therapy using compounds with affinity to both ssts and D2R (22).

The potent antisecretory properties of SS-14 have facilitated the development of pharmacological treatments for functional neuroendocrine tumors (NETs); however, the clinical utility of SS-14 itself is limited by its short half-life (23). Consequently, a number of stable SSA have been synthesized, aimed primarily at metabolic stability and multireceptor targeting, and these analogues have predominantly been characterized according to their binding profiles. The SSA octreotide and lanreotide bind with high subnanomolar affinity to sst2, have moderate affinity to sst3 and sst5, and exhibit very low or no binding to sst1 and sst4 (24, 25). Pasireotide (SOM230) binds with high affinity to all ssts except sst4 (26). In contrast to octreotide, pasireotide exhibits particular high subnanomolar affinity to sst5. Somatoprim (DG3173) exhibits a unique binding profile in that it binds with high affinity to sst2, sst4, and sst5 but not to sst1 or sst3 (27). BIM-23A760, a chimeric compound, binds with very high affinity to sst2 and to D2Rs (28).

Whether these compounds exhibit full or partial agonistic properties upon interaction with individual ssts remains largely unknown due to limited availability of methods that allow a direct assessment of GPCR activation in intact cells. Most techniques commonly used to estimate Gi-coupled receptor activity rely on activation of the Gα-subunit. Among the most widely used functional assays to study GPCR activation are measurements of guanosine-5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) binding, cAMP assays, calcium assays, and reporter assays. Although GTPγS binding reflects an early event of GPCR activation, cells have to be permeabilized or disrupted during the assay. cAMP measurements of Gi-coupled receptors require prestimulation of adenylate cyclase with forskolin to artificially elevate cAMP levels. Ca2+ efflux assays require the expression of a chimeric G protein (Gαqi5). Thus, there is an urgent need for an easy-to-perform and HTS-compatible assay format that allows reliable detection of Gi-coupled receptors activation in both intact permanent and primary endocrine cells.

In this work, we used the mouse corticotrope cell line AtT-20 as endogenous source of ssts and their relevant effector system. In AtT-20 cells, 2 clinically important sst subtypes, namely sst2 and sst5, are expressed (29). In addition, both GIRK1 and GIRK2 are present in these cells, and the presence of such channels is a precondition for agonist-induced membrane hyperpolarization (30). Agonist-induced hyperpolarization can be measured by conventional patch clamp techniques or detection of changes in fluorescence intensity of improved fluorescent oxonol dyes, which distribute throughout the cell membrane. In the present study, we used later approach developed by Vazquez et al (31) and Walsh (32) with modifications introduced by Knapman et al (33, 34) to establish a noninvasive read-out allowing the rapid pharmacological examination of novel SSA and D2R agonists taking advantage of one of their common effector systems.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

DNA for all human sst subtypes and D2R was obtained from University of Missouri (UMR) cDNA Resource Center. In addition, the coding sequence for an amino-terminal Hemagglutinin (HA)-tag was added for human somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (hsst2), human somatostatin receptor subtype 4 (hsst4), and human Dopamine receptor subtype 2 (hD2R).

Cell culture and transfection

AtT20-D16v-F2 cells were obtained from American Type Tissue Culture Collection and cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin, and L-glutamine. Cells were grown in an incubator at 37°C maintaining 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding for wild-type ssts and D2R using TurboFect according to manufacturer's instruction (Thermo Scientific). Stable transfectants were selected in the presence of geneticin (400 μg/mL). Cells were characterized using Western blot analysis (Supplemental Figure 1).

Primary culture

Experiments were performed on whole pituitary extracts from mice with a C57BL/J6 background. All adult male and female animals used in this study were older than 10 weeks. For all animal procedures, ethical approval was sought before the experiments according to national and institutional requirements. All handling was approved by the animal committee. Mice were housed under standard conditions in a climate-controlled room on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle and fed regular chow ad libitum. For dissections of the pituitary gland, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and then decapitated. The brain was swiftly removed. Pituitary glands were gently detached from the sella turcica and shortly rinsed in PBS. Material was transferred in digestion buffer containing collagenase P (50 U/mL) in PBS and incubated at 37°C at 150 rpm in a shaking water bath. After 15 minutes 1 mL of trypsin-EDTA solution was added and incubated for another 5 minutes. Finally, cells were dissociated mechanically by repeated pipetting, centrifuged, and transferred into DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin, and L-glutamine. Cells were allowed to settle and kept in a CO2 incubator for 24 hours before measurements. Separated cells of one pituitary gland were split equally and plated each in a 90-μL volume in 3 wells of a black-walled, clear-bottomed 96-well microplate. Approximately 70 000 cells were plated into 1 single well. Cells were allowed to settle for 4 hours before being exposed to pertussis toxin (PTX). For every experiment, cells of 2 wells were treated with agonist solution, whereas cells of the other well were treated with vehicle as control.

Drugs and chemicals

Somatostatin (SS-14) was obtained from Bachem. BIM-23926, BIM-23120, BIM-23268, BIM-23627, and BIM-23A760 (sst2-D2R chimera) were provided by Dr Michael Culler (Ipsen). Octreotide and pasireotide (SOM230) were provided by Dr Herbert Schmid (Novartis). Somatoprim (DG3173) was provided by Dr Carsten Dehning (Aspireo). L-796/778 and L-803/087 were provided by Dr Susan Rohrer (Merck), dopamine was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and tertiapin-Q (TPN-Q) was from Alomone Labs. Receptor affinities of test compounds are given in Supplemental Table 1.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultivated cells were obtained using a peqGOLD Total RNA kit (Peqlab). DNase-treated total RNA was first amplified with oligo(dT) primers and reverse transcribed with an improved version of Maloney murine leukemia virus transcriptase SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Primers were synthesized by Eurofins. Primer sequences used are given in Supplemental Table 2. PCR was performed using TopTaq Polymerase (QIAGEN). Amplification profile was performed as follows: 95°C for 3 minutes, 35 cycles at 95°C at 95°C for 50 seconds, 59°C for 50 seconds, and 72°C for 50 seconds, followed by 3 minutes at 72°C. PCR efficiency was determined by performing a reaction targeting Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Antibodies

The rabbit monoclonal antibodies anti-hsst1 antibody (UMB-7), anti-hsst2A antibody (UMB-1), anti-hsst3 antibody (UMB-5), and anti-hsst5 antibody (UMB-4) were obtained from Abcam-Epitomics and have been extensively characterized previously (17, 35–37). The rabbit polyclonal anti-rsst5 antibody (6003) was generated against the carboxy-terminal tail of rat sst5. The identity of the peptide used for immunizations was QATLPTRSCEANGLMQTSRI, which corresponds to residues 344–363 (19). This sequence shares a homology of 90% with the very distal carboxyl-terminal sequence of mouse sst5. In addition, the rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (0631) was used as described previously (38).

Western blot analysis

AtT-20 cells were plated onto 60-mm dishes and grown to 80% confluence. Cells were lysed in detergent buffer containing 20mM HEPES (pH 7.40), 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% sodium docecyl sulfate, 0.2mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 10-mg/mL leupeptin, 1-mg/mL pepstatin A, 1-mg/mL aprotinin, and 10-mg/mL bacitracin. The glycosylated receptors were enriched using wheat germ lectin-agarose beads as described (39). Proteins were eluted from beads using SDS-sample buffer for 25 minutes at 42°C and then resolved on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After electroblotting, membranes were incubated with either the rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-1 at a dilution of 1:200, the rabbit polyclonal antibody (6003) at a dilution of 1:500 or the rabbit anti-HA antibody (0631) at a dilution of 1:1000 followed by a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antirabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham).

Immunohistochemistry

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice weighing 20–25 g were killed, and the pituitaries were immersed in 10% buffered formalin solution for 72 hours and embedded in paraffin blocks. From these paraffin blocks, 4-μm-sections were prepared and floated onto positively charged slides. Immunostaining was performed by an indirect peroxidase labeling method as described previously (40). Briefly, sections were dewaxed, microwaved in 10mM citric acid (pH 6.0) for 16 minutes at 600 W and incubated with the rabbit monoclonal anti-sst2 antibody UMB-1 (cell culture supernatant) at a dilution of 1:10 overnight at 4°C. Detection of primary antibody was performed using a biotinylated antirabbit IgG followed by an incubation with peroxidase-conjugated avidin (Vector Laboratories). Binding of the primary antibody was visualized using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in acetate buffer (BioGenex). Sections were then rinsed, counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin, and mounted in Vectamount mounting medium (Vector Laboratories).

Membrane potential assay

For membrane potential measurements AtT-20 cells were plated into poly-L-lysine covered 96-well plates and cultivated for 48–72 hours to reach a confluency of 70%–80%. In each well, 40 000 cells were plated in a volume of 200 μL. Cells were then washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), buffered with HEPES 20mM (pH 7.4), containing 1.3mM CaCl2, 5.4mM KCl, 0.4mM K2HPO4, 0.5mM MgCl2, 0.4mM MgSO4, 136.9mM NaCl, 0.3mM Na2HPO4, 4.2mM NaHCO3, and 5.5mM glucose. Membrane potential dye (FLIPR Membrane Potential kit BLUE; Molecular Devices) was reconstituted according to manufacturer's instructions. A total of 90 μL of HBSS/HEPES and an equal volume of assay dye solution were added to the cells and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C. Measurements were executed in a FlexStation 3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). All measurements were conducted at 37°C. Compounds were injected in a volume of 20 μL. An equal concentration of solvent was used as vehicle control.

Test compound preparation

Agonists and antagonists were diluted in HBSS, buffered with 20mM HEPES (pH 7.4) at 10 times the final concentration to be assayed. Stock solutions for all agonists were prepared with water as solvent, with the exception of L-796/778, which was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). For vehicle control HBSS, buffered with 20mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing the same fraction of water or DMSO as the solution containing agonist/antagonist was used. Cells were exposed to a maximum concentration of 0.1% DMSO.

Kinetic imaging and data analysis

Cell plates and compound plates were loaded onto a FlexStation 3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Appropriate baseline readings were taken (excitation 530nm and emission 565 nm) for 60 seconds in an interval of 1.8 seconds. Raw data, normalized to the first data point of baseline, were collected using SoftMax Pro Software. Raw data were processed using custom programs in Microsoft Excel where each data point of the probe to be determined was subtracted from its cognate vehicle data point recorded at the same time. Finally, data were plotted with OriginPro to obtain real-time kinetics or to evaluate dose-response relationships. Data analysis was performed using a 4-parameter nonlinear regression for fitting concentration-response curves. Statistical analysis was performed with OriginPro using descriptive statistical tools as indicated. All data are given as mean ± SEM if not otherwise indicated. Statistical outliers were identified using Grubbs test. Student's t tests was used when comparing 2 data points. The analysis of 2 data points of vehicle vs agonist was accomplished by comparison of the maximum value of the agonist recorded compared with the vehicle signal given at that time. Significant changes are marked with an asterisk in figures, irrespective of the P value. Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's test were used to test for normality and equality of variance assumptions.

Results

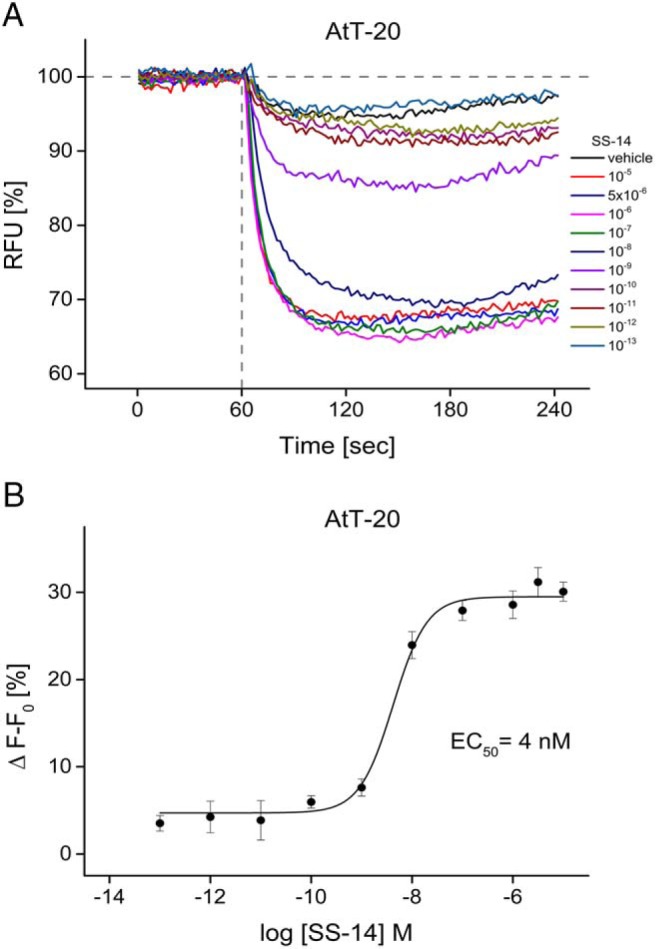

In AtT-20 cells loaded with membrane potential dye, addition of SS-14 induced a rapid dose-dependent decrease in fluorescence intensity, which is indicative of membrane hyperpolarization (Figure 1A). After addition of saturating concentrations of SS-14, maximal hyperpolarization was reached after 60 seconds. The maximum was used to generate a dose-response curve. The half-maximal effective concentration EC50 was 4nM (Figure 1B). To test for a bidirectional change of fluorescence signal, cells were exposed to various concentrations of potassium chloride (data not shown). This depolarizing agent induced a fast and concentration-dependent increase in fluorescence signal. Z-factor for SS-14 vs vehicle was 0.63 ± 0.13 of 14 independent day-to-day experiments, conducted as duplets or triplets of a solution of 10μM SS-14 vs vehicle solution (HBSS/HEPES 20mM) containing the same amount of diluent. Determination of Z-factor was performed according to Zhang et al (41).

Figure 1. Somatostatin-induced changes in membrane potential in AtT-20 cells.

A, Fluorescent traces obtained after addition of SS-14 in a concentration range of 0.1pM to 10μM. Data were obtained using FlexStation3 running SoftMax Pro Microplate Data Acquisition and Analysis Software (Molecular Devices) by measuring a 60-second baseline of each well before agonist exposure. Results show a representative 1-day experiment where each curve represents a single well. Data are presented as relative decrease of fluorescence signal normalized to time of agonist exposure. B, Dose-response curve of SS-14 in AtT-20 cells. Dose-response curve was obtained with OriginPro using sigmoideal nonlinear fitting function of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate (mean ± SD). Vehicle-induced changes in fluorescence signal were subtracted from signals obtained by agonist-containing solutions. Data are expressed as Δ F − F0 (%).

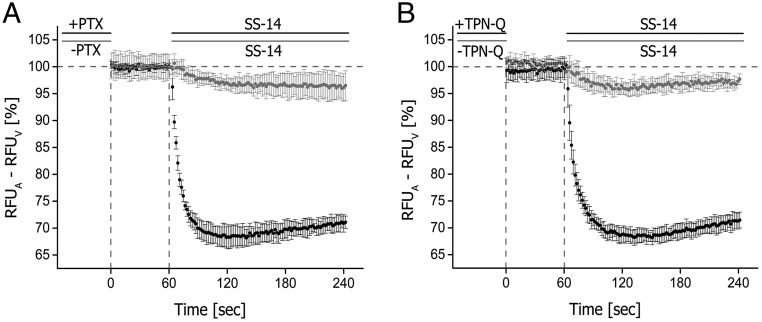

An overnight incubation with PTX decreased signal magnitude by 94.2 ± 3.1% (n = 6; **, P < .01) in comparison with PTX-untreated cells (Figure 2A). The SS-14-activated current was almost completely blocked (93.2 ± 2.9%, n = 5; **, P < .01) by preincubation with the GIRK channel blocker TPN-Q (Figure 2B). TPN-Q is a potent and selective blocker for Kir1.1 renal outer medullary potassium, Kir3.1-Kir3.4 channels and calcium activated large conductance potassium channels (big potassium channels) (42, 43). However, for a complete block of big potassium channels extended, incubation times of 15–20 minutes are required, whereas a TPN-Q block of renal outer medullary potassium channels can take up to 10 minutes (44). We therefore conclude that TPN-Q targets primarily GIRK channels, which are endogenously expressed in AtT-20 cells along with a subset of other potassium and calcium channel described (45–47).

Figure 2. Characterization of somatostatin-induced membrane potential changes.

A, AtT-20 cells were either not exposed (−) or exposed (+) to 300-ng/mL PTX for 16 hours and subsequently stimulated with 1μM SS-14. B, AtT-20 cells were either not exposed (−) or exposed (+) to 500nM TPN-Q for 5 minutes and subsequently stimulated with 1μM SS-14 after baseline recording of 60 seconds. Shown are representative results of 3 independent experiments performed in quadruplicate (mean ± SD). Each point represents a relative change of fluorescence signal. Vehicle-induced changes in fluorescence signal (background) were subtracted from agonist-induced changes at a given concentration.

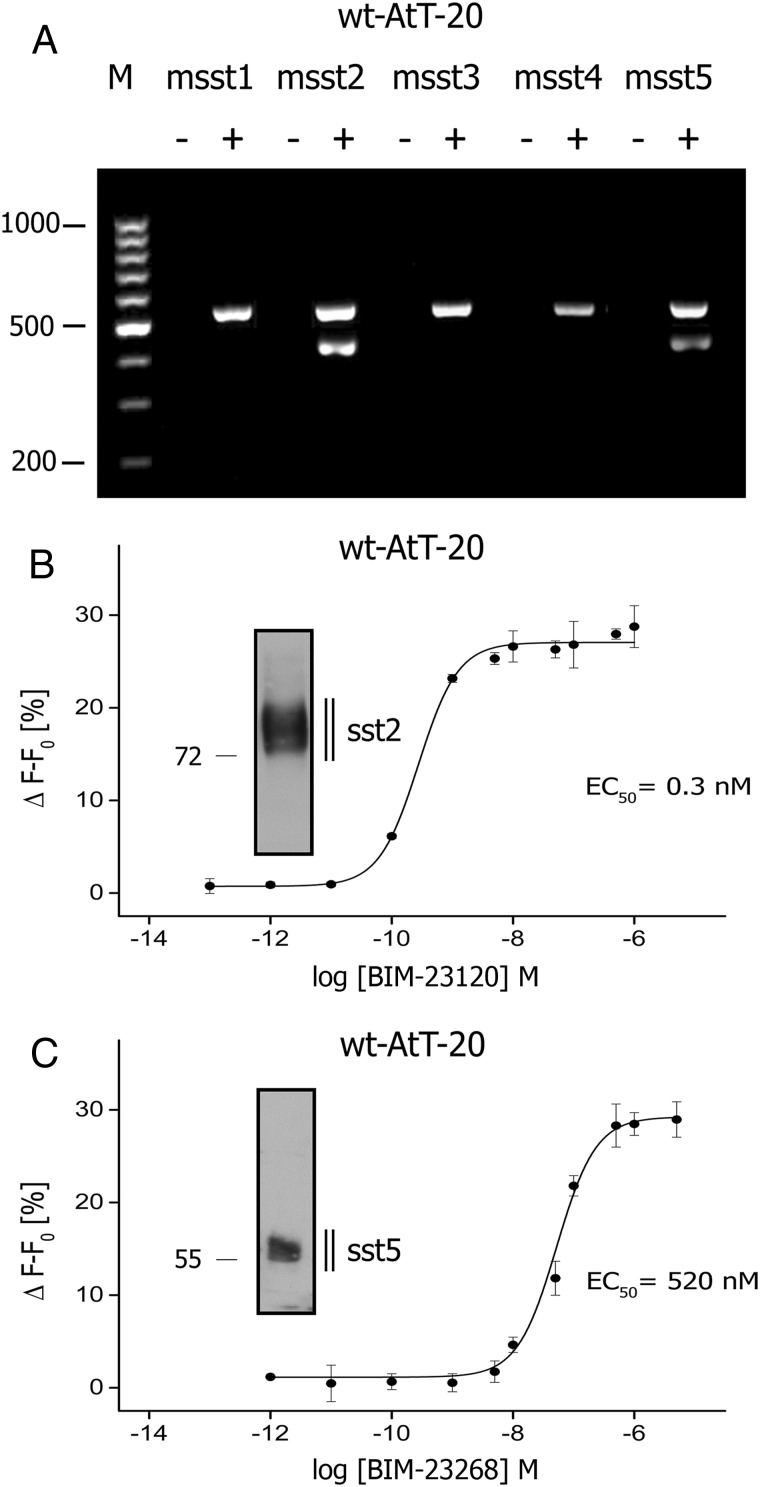

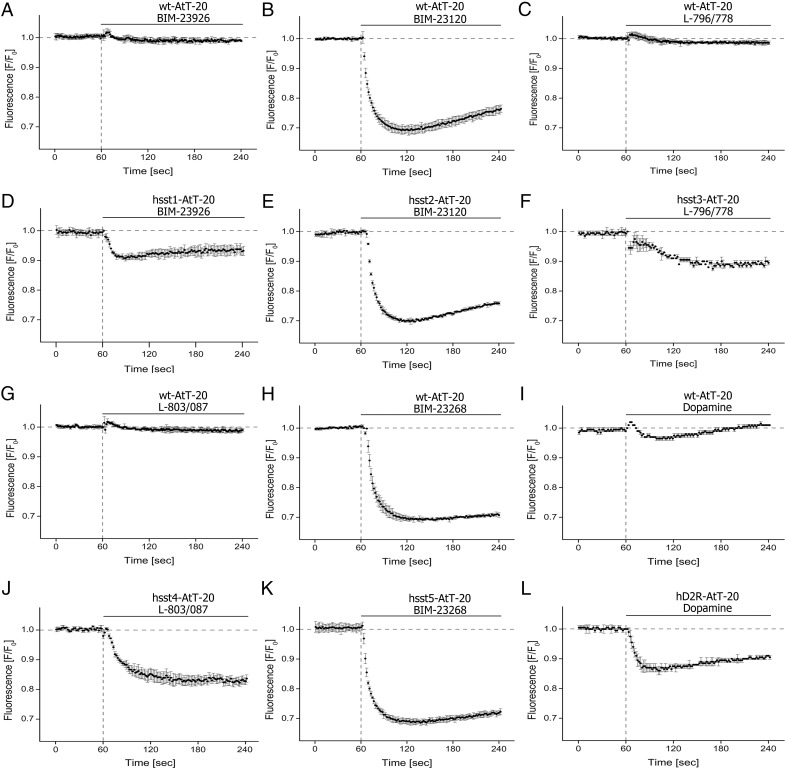

We then reassessed sst expression in AtT-20 cells using RT-PCR and Western blotting. PCR analysis indicated the existence of mRNA for mouse somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (msst2) and mouse somatostatin receptor subtype 5 (msst5) exclusively (Figure 3A). Western blot analysis confirmed expression of msst2 and msst5 in AtT20 cells (Figure 3, B and C). Exposure of AtT-20 cells with the sst2-selective agonist BIM-23120 and the sst5-selective agonist BIM-23268 revealed unique dose-response curves with EC50 values of 2.8nM and 520nM, respectively (Figure 3, B and C). The sst1-selective agonist BIM-23926 did not evoke any detectable change in membrane potential when exposed to wild-type AtT-20 cells 0.7 ± 0.5% (n = 3; n.s.) (Figure 4A). However, when AtT-20 cells were stably transfected with hsst1, stimulation with a saturating concentration of BIM-23926 (10μM) evoked a clearly detectable change of 8.7 ± 1.4% (n = 5; *, P < .05) (Figure 4D). Similarly, the nonpeptidic sst3-selective agonist L-796/778 only evoked a minor decrease of fluorescence signal 1.1 ± 0.3% (n = 3; n.s.) (Figure 4C). However, when AtT-20 cells were stably transfected with hsst3, stimulation with a saturating concentration of L-796/778 (10μM) evoked a clearly detectable change of 11.2 ± 1.1% (n = 5; *, P < .05) (Figure 4F). Also the sst4-selective agonist L-803/087 did not evoke any change in membrane potential in wild-type cells but in hsst4-transfected AtT-20 cells with a change of 17.4 ± 0.7% (n = 5; *, P < .05) (Figure 4, G and J). These results indicate that all sst receptor subtypes can couple to GIRK channels in pituitary cells and are sensitive to TPN-Q (data not shown). D2R is another major Gi protein-coupled receptor involved in the regulation of hormone secretion from the anterior pituitary. Nevertheless, exposure of wild-type AtT-20 cells to dopamine did not induce a robust membrane hyperpolarization with 2.9 ± 0.7% (n = 3; n.s.) (Figure 4I). Again overexpression of human D2R was required to facilitate activation of GIRK channels by dopamine with a change of 13.9 ± 1.5 (n = 4; *, P < .05) (Figure 4L). Exposure to the sst2-selective agonist BIM-23120 induced a rapid and consistent decrease in fluorescence signal in wild-type cells by 29.2 ± 4.0% (n = 5; *, P < .01) with a latency of 55 ± 7 seconds (n = 5) (Figure 4B). Latency is defined as the time interval from agonist exposure to the maximum decrease in fluorescence signal. No further decrease of fluorescence signal was detected in AtT-20 cells stably expressing hsst2 (29.6 ± 3.1%, n = 4; *, P < .01) (Figure 4E). Similarly, the sst5-selective agonist, BIM-23268, induced a rapid decrease of the fluorescence signal in wild-type AtT-20 cells with a latency of 68 ± 15 seconds (n = 5) and a maximum amplitude of 30.1 ± 2.1% (n = 5; *, P < .01) (Figure 4H), whereas in AtT-20 cells stably expressing hsst5, no further increase in signal intensity was detected compared with untransfected cells (30.4 ± 1.4%, n = 4; *, P < .01) (Figure 4K). This lack of signal gain after overexpression of sst2 or hsst5 is presumably due to the fact that the maximum possible effect of this effector system has already been reached after activation of endogenously expressed ssts. Receptor expression was confirmed using Western blotting (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 3. Analysis of functional ssts in AtT-20 cells.

A, Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products for mouse sst1, sst2, sst3, sst4, and sst5 receptors and GAPDH in AtT-20 cells. Reverse transcriptase was either not added (−), referring to lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, or added (+), referring to lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 to RNA isolates before converting into cDNA. The position of the PCR fragment is indicated by the DNA molecular weight marker (100–1000 bp). B, Dose-response curve for BIM-23120 (sst2 selective). AtT-20 cells were exposed to various concentrations of BIM-23120 ranging from 0.1pM to 1μM. Inset, Western blot analysis of sst2 in AtT-20 cells using the anti-sst2 antibody (UMB-1). The position of the molecular mass markers is indicated on the left (in kDa). C, Dose-response curve for BIM-23268 (sst5 selective). AtT-20 cells were exposed to various concentrations of BIM-23268 ranging from 1pM to 5μM. Inset, Western blot analysis of sst5 in AtT-20 cells using the anti-rsst5 antibody (6003). The position of the molecular mass markers is indicated on the left (in kDa). Dose-response curve was obtained with OriginPro using sigmoideal nonlinear fitting function of 4 independent experiments performed in duplicate (mean ± SEM). Vehicle-induced changes in fluorescence signal were subtracted from signals obtained by agonist-containing solutions. Shown are representative results from 1 of 3 independent experiments. Data are expressed as Δ F − F0 (%).

Figure 4. Response to sst subtype-selective agonists.

A, Wild-type AtT-20 were treated with BIM-23926 (sst1-selective). B, Wild-type AtT-20 were treated with BIM-23120 (sst2 selective). C, Wild-type AtT-20 were treated with L-796/778 (sst3 selective). D, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with hsst1 were treated with BIM-23926. E, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with hsst2 were treated with BIM-23120. F, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with hsst3 were treated with L-796/778. G, Wild-type AtT-20 cells were treated with L-803/087 (sst4 selective). H, Wild-type AtT-20 cells were treated with BIM-23268 (sst5 selective). I, Wild-type AtT-20 cells were treated with dopamine. J, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with hsst4 were treated with L-803/087. K, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with hsst5 were treated with BIM-23268 (sst5 selective). L, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with D2R were treated with dopamine. All agonist exposures were performed at a concentration of 1μM. Average responses of 5 independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 5). Data of relative fluorescence signals shown were obtained by subtraction of vehicle-induced fluorescence changes from solutions containing agonists and expressed as F/F0.

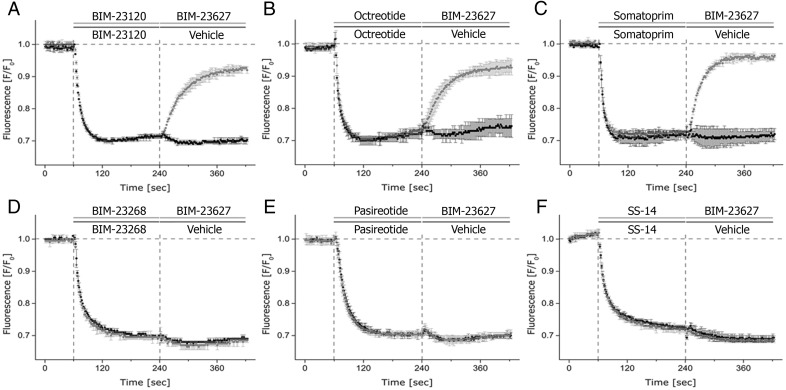

To evaluate the in vitro activity of multi-sst ligands octreotide, pasireotide, and somatoprim in a cell system expressing sst2 and sst5 endogenously, we first exposed AtT-20 cells to these compounds, after which a second exposure to either the sst2-selective antagonist BIM-23627 or vehicle was performed. Initially, we validated the selectivity of BIM-23627 in the presence of the sst2-selective agonist BIM-23120 and sst5-selective agonist BIM-23268. Addition of BIM-23627 induced a reversal of the BIM-23120-induced hyperpolarization towards baseline level (Figure 5A). In contrast, in cells treated with BIM-23268, no such change in fluorescence signal after addition of BIM-23627 could be detected (Figure 5D), even when BIM-23268 and BIM-23627 were applied in a molar ratio of 1:10 (data not shown). However, in the presence of octreotide or somatoprim, addition of the sst2-selective antagonist BIM-23627 induced a strong reversal membrane hyperpolarization towards baseline level (Figure 5, B and C). No such change in fluorescence signal intensity was noted with pasireotide- and SS-14-treated cells (Figure 5, E and F) even not in a ratio of 1:10 (data not shown). These findings suggest that octreotide and somatoprim exhibit strong activity towards the sst2 receptor. When the sst2 receptor is blocked, pasireotide and SS-14 can still signal via the sst5 receptor in this system. BIM-23627 was identified as a competitive antagonist without intrinsic affinity in this assay by exposure of a 10μM solution to AtT-20 cells (no change in signal intensity was detected). Preincubation at 1nM, 5nM, and 10nM BIM-23627 before exposure to various concentrations of SS-14 revealed a parallel rightward shift of the dose-response curve without effecting the maximal action of the agonist (Emax) (data not shown).

Figure 5. Block with sst2-selective antagonist BIM-23627.

Primary agonist exposure was performed after recording baseline for 60 seconds. After 180 seconds, a secondary exposure was performed containing the sst2-selective antagonist BIM-23627 in a concentration of 10μM. Yielding a final molar agonist to antagonist ratio of 1:1. A, BIM-23120 (sst2-selective agonist). B, octreotide. C, somatoprim. D, BIM-23268 (sst5-selective agonist). E, pasireotide. F, SS-14. Shown are representative curves from 1 of 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data for relative fluorescence signals shown were obtained by subtraction of vehicle-induced fluorescence changes from solutions containing agonist/antagonist and expressed as F/F0.

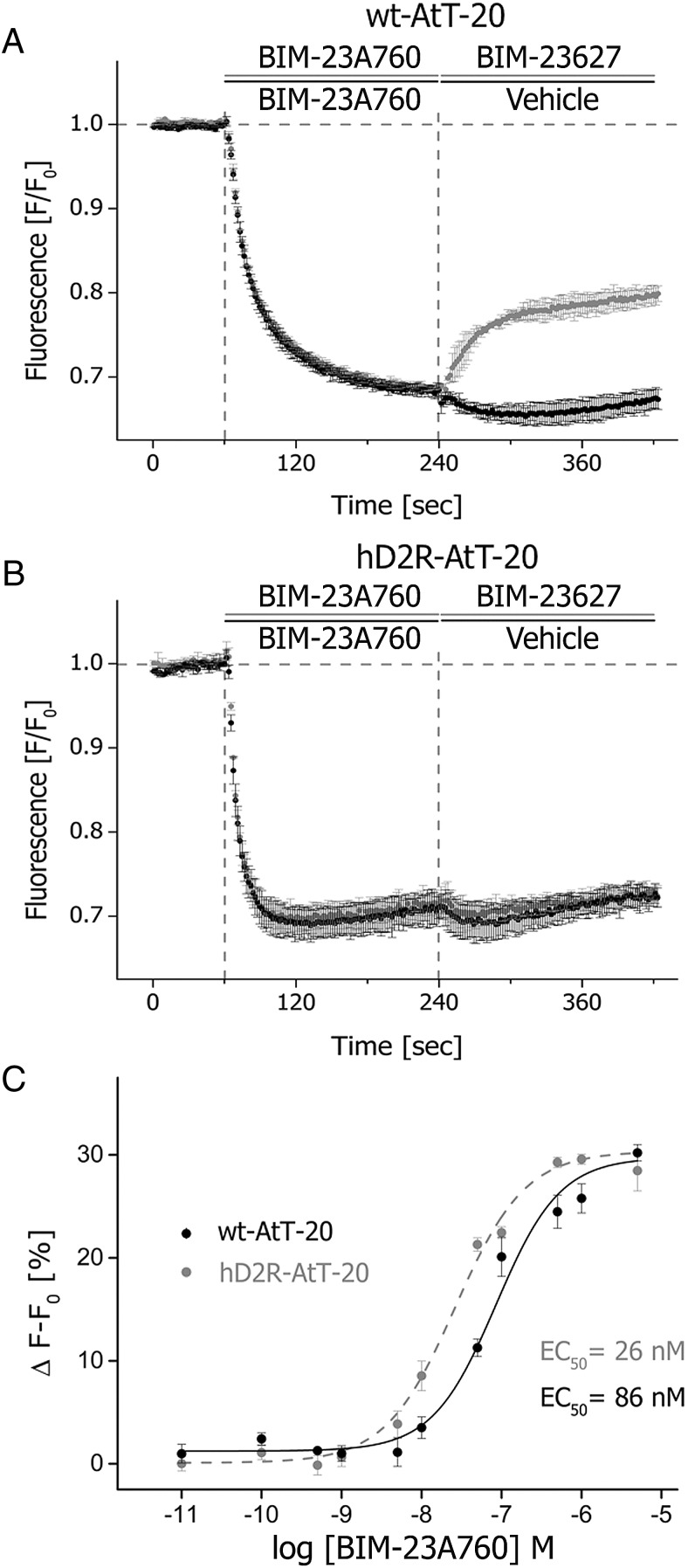

Next, we evaluated the in vitro activity of the chimeric molecule, BIM-23A760, which exhibits high affinity to both sst2 and D2Rs. In wild-type AtT-20 cells, exposure to the sst2-selective antagonist BIM-23627 induced a partial reversal of the BIM-23A760-induced hyperpolarization. At t = 360 seconds, a total difference of 13.2 ± 2.4 (F/F0) (n = 3; *, P < .05) was detected (Figure 6A). In contrast, no such reversal was detected in AtT-20 cells after heterologous expression of D2Rs (t = 360 s: 0.8 ± 0.4 [F/F0]; n = 3; n.s.) (Figure 6B). We conclude that in the absence of D2R BIM-23A760 mediates its activity primarily via activation of the sst2 receptor which is partially blocked by addition of BIM-23627. In the presence of D2Rs, however, BIM-23A760 mediates its activity via both sst2 and D2Rs, which cannot be blocked with BIM-23627. We than extended our study to evaluate the influence of D2R for the action of BIM-23A760 in a broader dose-response interval. Thus, analysis of dose-response curves indicated a leftward shift in sst2-D2R-coexpressing cells compared with wild-type AtT-20 cells (Figure 6C). These findings suggest that the presence of D2Rs in addition to sst2 receptors strongly facilitated GIRK channel activation elicited by BIM-23A760.

Figure 6. Activity of the sst2–D2R chimeric compound, BIM-23A760, in the presence and absence of D2R.

A, Wild-type AtT-20 cells were initially stimulated with 10μM BIM-23A760. In a secondary experiment, 10μM BIM-23627 was added to yield a 1 μM to 1 μM (1:1) ratio of agonist to antagonist. B, AtT-20 cells stably transfected with D2Rs were stimulated in the same manner as reported in A. C, AtT-20 cells either expressing D2Rs or not were exposed to BIM-23A760 in a concentration range of 10−5 M to 10−12 M to yield a dose-response curve. Fitting was performed using a Levensberg-Marquadt Iteration algorithm and subsequent using a 4-parameter nonlinear regression for fitting concentration-response curves with OriginPro software. Each data point was determined in duplicates on 3 different occasions.

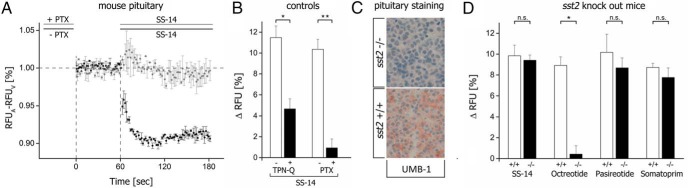

We then tested whether sst-activated GIRK currents are also detectable in primary pituitary cultures. In fact, SS-14 elicited a fast and consistent decrease of fluorescent signal under these conditions (Figure 7A). The relative change of fluorescence signal intensity normalized to baseline was approximately one third of that detected in AtT-20 cells, most likely due to the cellular heterogeneity of the primary cells. Overnight incubation with PTX prevented SS-14-induced signaling (Figure 7, A and B). Exposure to TPN-Q significantly reduced SS-14 mediated-effects to 4.7 ± 1.0% (n = 8, consisting of 4 males and 4 females; *, P < .05) vs 11.5 ± 1.1% (n = 7, consisting of 4 males and 3 females) for the cells left untreated.

Figure 7. Primary pituitary culture of wild-type and sst2−/− mice.

A, Membrane potential assay measurements in primary mouse pituitary cultures. Cells were either not exposed (−) or exposed (+) to 300-ng/mL PTX for 16 hours and subsequently stimulated with 10μM SS-14. Each trace represents data from 5 animals (each 3 males and 2 females) (mean ± SEM). Background fluorescence (F0) of vehicle was subtracted from agonist-induced fluorescence signal (F) (F − F0). B, left scale bar, Total pituitary cell extracts of wild-type mice were pretreated with 500nM TPN-Q for 5 minutes before agonist exposure with 10μM SS-14. Right scale bar, Total pituitary extracts of wild-type mice were pretreated with (+) 300-ng/mL PTX or left untreated (−) for 16 hours and stimulated with 10μM SS-14. C, Immunohistochemical staining for sst2 in mouse pituitary formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded pituitary tissue using rabbit monoclonal anti-sst2 antibody UMB-1. D, Mouse pituitary extracts of wild-type (+/+) vs sst2 knockout (−/−) mice were exposed to 10μM solutions of SS-14, octreotide, pasireotide, or somatoprim. Statistical analysis was performed according to Mann-Whitney U test. Data are given as relative changes in fluorescence signal compared with vehicle-induced background signal determined as Δ relative fluorescence unit (RFU) (%).

In wild-type mice (sst2+/+), octreotide, pasireotide, and somatoprim induced a fast and consistent change in fluorescence signal intensity which was comparable with that observed with SS-14 (Figure 7D). Interestingly, in primary pituitary cultures prepared from sst2−/− mice, the octreotide-induced hyperpolarization was almost completely abolished with 0.4 ± 0.8% (n = 6, consisting of 3 males and 3 females; *, P < .05) compared with wild-type mice with 8.9 ± 0.8% (n = 6, consisting of 3 males and 3 females). Notably, SS-14 (sst2−/− 9.8 ± 1.0%, n = 8, consisting of 5 males and 3 females/wt 9.42 ± 0.5%, n = 9, consisting of 5 males and 4 females), pasireotide (sst2−/− 10.2 ± 1.7%, n = 6, consisting of 3 males and 3 females/wt 9.42 ± 0.5%, n = 5, consisting of 3 males and 2 females), and somatoprim (sst2−/− 8.7 ± 0.4%, n = 5, consisting of 3 males and 2 females/wt 7.8 ± 0.9%, n = 5, consisting of 3 males and 2 females) were still able to elicit strong responses (Figure 7C). These results identify sst2 as pharmacological target for octreotide. In contrast, pasireotide and somatoprim can also activate other ssts present in the anterior pituitary.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, different biochemical techniques for the elucidation of intracellular signaling events in cells and tissues have allowed us to gain important insight into the physiology of the endocrine system. Nearly all of these techniques require the expression of artificial effectors or disruption of the samples in order to assess the second messenger content. Therefore, these methods generally lack temporal and spatial resolution. Gβγ-induced changes in membrane potential are conventionally measured using electrophysiological techniques, such as patch clamp analysis, which require an exigent experimental setting and allow monitoring of single cells only. Furthermore, these assays do not allow the increased throughput that is required for a detailed pharmacological analysis and characterization of novel ligands. On the other hand, automated patch clamp allows a high-throughput compared with single-cell patching, but still remains a highly cost-demanding alternative. Flux assays for monovalent ions such as rubidium (Rb+) and thallium (Tl+) may represent a possible alternative for measuring βγ-mediated GIRK activation. Although these assay formats specifically detect potassium-mediated changes of membrane potential, they do not integrate calcium, sodium or chloride channel-mediated currents. However, ssts and D2R have been reported to mediate part of their endocrine actions by inhibition of sodium or calcium channels (48–51). Thus, flux assays might not be applicable for other cell models with a distinctive set of effector currents.

Based on the observation that ssts and D2R couple to various calcium and potassium channels, we modified an assay to easily assess G protein signaling through these receptors. Here, we present an in vitro method that has proven to be suitable for target identification of multiple sst analogues. This voltage-sensitive method displays a high signal-to-noise ratio, exhibits a robust and highly reproducible signal after agonist exposure, and can be performed in live cells. AtT-20 cells express voltage-gated calcium channels and GIRK1/GIRK2 channels (9, 10, 52), and GIRK activation is a βγ-mediated process (53). In this study, we laid the foundation for this analysis with the appropriate controls necessary to validate this new assay for somatostatin and dopamine signaling. First, we reexamined the notion of sst-induced hyperpolarization in AtT-20 cells, originally reported by Vazquez et al (31) and Walsh (32). We then consequently expanded the protocol modified by Knapman et al (33, 34). Next, we extended our findings to analysis of single ssts (sst2 and sst5) to provide additional proof of this concept for mouse primary pituitary cultures. Furthermore, we used pertussis toxin to determine whether the effect of a compound is exerted by a Gi-coupled GPCR or another mechanism and exploited the selective GIRK channel blocker TPN-Q to describe the mechanism involved. We were able to largely confirm data published in earlier reports. This assay has already been used successfully for the characterization of a fluorescent sst agonist with very similar results for somatostatin yielding a pEC50 (negative logarithm of the half-maximal effective concentration) value of 8.4 ± 0.3 (54) and an EC50 of 4nM (32). Knapman et al proofed the value of this technique for the mouse μ-opioid receptor heterologously expressed in AtT-20 cells. Their findings regarding kinetic profiles and Emax of various μ-opioid receptor agonists are very similar to our findings for ssts and dopamine D2R. The suitability of this membrane potential assay was also reported for cannabinoid receptors, another important class A GPCR subfamily (55).

Previous reports suggested that in Xenopus laevis oocytes, all human sst receptor subtypes except sst1 couple to GIRK channels (12). Our results obtained in AtT-20 cells largely confirm these results, although hsst1 was also able to produce a robust signal.

These findings confirm the efficient heterologous expression of all sst subtypes in AtT-20 cells (Supplemental Figure 1) and their functional coupling to GIRK channels for all ssts. Thus, we demonstrated that this assay is also applicable for sst1, sst3, and sst4. This is important because sst1 and sst5 are the predominant receptor subtypes expressed in prolactinomas (56), whereas sst3 and sst2 are highly expressed in nonfunctioning pituitary tumors (57). Although there are some sst subtype-selective molecular tools available to address single ssts, there is still demand for a highly selective sst5 antagonist.

Our findings for mouse primary pituitary cells indicated a Gi protein-mediated functional response to SS-14 largely involving a TPN-Q-sensitive process using this method. However, we are unable to allocate a single mechanism involved to a particular cell type in the presence of various functional cells such as somatotrophs, lactotrophs, gonadotrophs, and thyrotrophs within the anterior pituitary lobe. Presenting only a total response to SS-14 other methods are required to separate single cells of the anterior pituitary lobe to identify cell type-specific mechanisms. Nevertheless, expression of ssts was demonstrated on the mRNA level (58).

Octreotide and lanreotide are currently used in clinical practice as first-choice medical treatments for NET and GH adenomas (59–61). Recently, the multi-sst analogue pasireotide has been approved for the treatment of Cushing's disease, a pathology linked to high sst5 expression (62, 63). In contrast to octreotide, pasireotide exerts high subnanomolar affinity to sst5 (64); however, pasireotide modulates sst receptor trafficking in a manner distinct from that of octreotide (65). In addition, the heptapeptide somatoprim, which exhibits a unique affinity profile by binding to sst2, sst4, and sst5 with nanomolar affinity (27), is currently undergoing clinical and preclinical evaluation (66). Somatoprim remains a promising candidate for therapeutic intervention, because this drug suppresses GH secretion from acromegalic pituitary adenomas, including cases refractory to conventional sst-targeting therapy (67). In another study, somatoprim suppressed GH release in acromegalic tumors in vitro to a similar extent as octreotide. Moreover, somatoprim was effective in more cases than octreotide (68). In line with these findings, our results identify sst2 as the pharmacological target for octreotide, whereas pasireotide and somatoprim clearly activate other sst receptors in addition to sst2 in the anterior pituitary. In our study, BIM-23627 was unable to antagonize the effects of pasireotide in AtT-20 cells in accordance with the findings in primary culture of pituitary extracts of sst2 knockout mice.

Most NETs of the gastroenteropancreatic system coexpress sst2, sst5, and D2R, which are also abundantly expressed in several types of pituitary adenomas, including GH and ACTH-secreting adenomas. Notably, D2R agonists remain the mainstay treatment for the management of prolactinomas (69). Notably, after overexpression of D2Rs in AtT-20 cells, we detected similar signals after dopamine application compared with SS-14. Thus, targeting both somatostatin and dopamine receptors with a single compound, such as the sst2-D2R chimeric compound BIM-23A760, is a promising alternative. In fact, we found that BIM-23A760-mediated GIRK channel activation was strongly enhanced in the presence of both sst2 and D2R in AtT-20 cells.

In conclusion, we have adapted a novel fluorescence-based method for characterization of stable multi-sst ananalogues in an endogenously expressing cell line as well as in primary pituitary cells. Our results clearly demonstrate that stable somatostatin analogues exhibit strikingly different activity profiles. Octreotide mediates its pharmacological effects via the sst2 receptor, whereas pasireotide activates sst5 and somatoprim activates both sst2 and sst5 receptors in the anterior pituitary. In addition, BIM-23A760 recruits sst2 and D2Rs to synergistically enhance signaling. We anticipate that the concept of measuring the membrane potential using fluorescent dyes will be widely applicable in the field of endocrinology for both target identification and rapid pharmacological characterization of novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Amelie Lupp for the immunohistochemical stainings of the mouse pituitary and Ulrike Schiemenz for genotyping the mice.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SCHU924/10-4 and the Deutsche Krebshilfe Grant 109952.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SCHU924/10-4 and the Deutsche Krebshilfe Grant 109952.

Footnotes

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- D2R

- dopamine D2 receptor

- GIRK

- G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channel

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- HA

- Hemagglutinin

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- hsst1

- human somatostatin receptor subtype 1

- hsst2

- human somatostatin receptor subtype 2

- hsst3

- human somatostatin receptor subtype 3

- hsst4

- human somatostatin receptor subtype 4

- hsst5

- human somatostatin receptor subtype 5

- msst2

- mouse somatostatin receptor subtype 2

- msst5

- mouse somatostatin receptor subtype 5

- NET

- neuroendocrine tumor

- n.s.

- not significant

- PTX

- pertussis toxin

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SS-14

- somatostatin

- SSA

- somatostatin analogue

- sst

- somatostatin receptor

- TPN-Q

- tertiapin-Q.

References

- 1. Colao A, Pivonello R, Di Somma C, Savastano S, Grasso LF, Lombardi G. Medical therapy of pituitary adenomas: effects on tumor shrinkage. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009;10(2):111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rocheville M, Lange DC, Kumar U, Patel SC, Patel RC, Patel YC. Receptors for dopamine and somatostatin: formation of hetero-oligomers with enhanced functional activity. Science. 2000;288(5463):154–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Epelbaum J, Enjalbert A, Krantic S, et al. Somatostatin receptors on pituitary somatotrophs, thyrotrophs, and lactotrophs: pharmacological evidence for loose coupling to adenylate cyclase. Endocrinology. 1987;121(6):2177–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mania-Farnell BL, Farbman AI, Bruch RC. Bromocriptine, a dopamine D2 receptor agonist, inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity in rat olfactory epithelium. Neuroscience. 1993;57(1):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Obadiah J, Avidor-Reiss T, Fishburn CS, et al. Adenylyl cyclase interaction with the D2 dopamine receptor family; differential coupling to Gi, Gz, and Gs. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1999;19(5):653–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Florio T, Pan MG, Newman B, Hershberger RE, Civelli O, Stork PJ. Dopaminergic inhibition of DNA synthesis in pituitary tumor cells is associated with phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(34):24169–24172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liebow C, Reilly C, Serrano M, Schally AV. Somatostatin analogues inhibit growth of pancreatic cancer by stimulating tyrosine phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(6):2003–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kisilevsky AE, Zamponi GW. D2 dopamine receptors interact directly with N-type calcium channels and regulate channel surface expression levels. Channels (Austin). 2008;2(4):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis DL, Weight FF, Luini A. A guanine nucleotide-binding protein mediates the inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium current by somatostatin in a pituitary cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(23):9035–9039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dousmanis AG, Pennefather PS. Inwardly rectifying potassium conductances in AtT-20 clonal pituitary cells. Pflugers Arch. 1992;422(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gregerson KA, Flagg TP, O'Neill TJ, et al. Identification of G protein-coupled, inward rectifier potassium channel gene products from the rat anterior pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 2001;142(7):2820–2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreienkamp HJ, Hönck HH, Richter D. Coupling of rat somatostatin receptor subtypes to a G-protein gated inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK1). FEBS Lett. 1997;419(1):92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Webb CK, McCudden CR, Willard FS, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Oxford GS. D2 dopamine receptor activation of potassium channels is selectively decoupled by Gα-specific GoLoco motif peptides. J Neurochem. 2005;92(6):1408–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R. Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(6):724–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guillemin R. Hypothalamic hormones a.k.a. hypothalamic releasing factors. J Endocrinol. 2005;184(1):11–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Day R, Dong W, Panetta R, Kraicer J, Greenwood MT, Patel YC. Expression of mRNA for somatostatin receptor (sstr) types 2 and 5 in individual rat pituitary cells. A double labeling in situ hybridization analysis. Endocrinology. 1995;136(11):5232–5235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fischer T, Doll C, Jacobs S, Kolodziej A, Stumm R, Schulz S. Reassessment of sst2 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4519–4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamberts SW, Macleod RM. Regulation of prolactin secretion at the level of the lactotroph. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(2):279–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schulz S, Handel M, Schreff M, Schmidt H, Hollt V. Localization of five somatostatin receptors in the rat central nervous system using subtype-specific antibodies. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94(3–4):259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reubi JC, Waser B, Schaer JC, Laissue JA. Somatostatin receptor sst1-sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28(7):836–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thodou E, Kontogeorgos G, Theodossiou D, Pateraki M. Mapping of somatostatin receptor types in GH or/and PRL producing pituitary adenomas. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(3):274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saveanu A, Jaquet P. Somatostatin-dopamine ligands in the treatment of pituitary adenomas. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009;10(2):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Longnecker SM. Somatostatin and octreotide: literature review and description of therapeutic activity in pancreatic neoplasia. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1988;22(2):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bruns C, Raulf F, Hoyer D, Schloos J, Lubbert H, Weckbecker G. Binding properties of somatostatin receptor subtypes. Metabolism. 1996;45(8 suppl 1):17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patel YC, Greenwood MT, Warszynska A, Panetta R, Srikant CB. All five cloned human somatostatin receptors (hSSTR1–5) are functionally coupled to adenylyl cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198(2):605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruns C, Lewis I, Briner U, Meno-Tetang G, Weckbecker G. SOM230: a novel somatostatin peptidomimetic with broad somatotropin release inhibiting factor (SRIF) receptor binding and a unique antisecretory profile. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146(5):707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Afargan M, Janson ET, Gelerman G, et al. Novel long-acting somatostatin analog with endocrine selectivity: potent suppression of growth hormone but not of insulin. Endocrinology. 2001;142(1):477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Culler MD. Somatostatin-dopamine chimeras: a novel approach to treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Horm Metab Res. 2011;43(12):854–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cervia D, Fehlmann D, Hoyer D. Native somatostatin sst2 and sst5 receptors functionally coupled to Gi/o-protein, but not to the serum response element in AtT-20 mouse tumour corticotrophs. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;367(6):578–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuzhikandathil EV, Yu W, Oxford GS. Human dopamine D3 and D2L receptors couple to inward rectifier potassium channels in mammalian cell lines. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;12(6):390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vazquez M, Dunn CA, Walsh KB. A fluorescent screening assay for identifying modulators of GIRK channels. J Vis Exp. 2012;(62). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walsh KB. Targeting GIRK channels for the development of new therapeutic agents. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Knapman A, Connor M. Fluorescence-based, high-throughput assays for μ-opioid receptor activation using a membrane potential-sensitive dye. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1230:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Knapman A, Santiago M, Du YP, Bennallack PR, Christie MJ, Connor M. A continuous, fluorescence-based assay of μ-opioid receptor activation in AtT-20 cells. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18(3):269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lupp A, Hunder A, Petrich A, Nagel F, Doll C, Schulz S. Reassessment of sst(5) somatostatin receptor expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-4. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94(3):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lupp A, Nagel F, Doll C, et al. Reassessment of sst3 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-5. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96(4):301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lupp A, Nagel F, Schulz S. Reevaluation of sst1 somatostatin receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues using the novel rabbit monoclonal antibody UMB-7. Regul Pept. 2013;183:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pfeiffer M, Koch T, Schröder H, Laugsch M, Höllt V, Schulz S. Heterodimerization of somatostatin and opioid receptors cross-modulates phosphorylation, internalization, and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):19762–19772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koch T, Schulz S, Pfeiffer M, et al. C-terminal splice variants of the mouse μ-opioid receptor differ in morphine-induced internalization and receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(33):31408–31414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lupp A, Danz M, Muller D. Morphology and cytochrome P450 isoforms expression in precision-cut rat liver slices. Toxicology. 2001;161(1–2):53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4(2):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jin W, Lu Z. A novel high-affinity inhibitor for inward-rectifier K+ channels. Biochemistry. 1998;37(38):13291–13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kanjhan R, Coulson EJ, Adams DJ, Bellingham MC. Tertiapin-Q blocks recombinant and native large conductance K+ channels in a use-dependent manner. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(3):1353–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kitamura H, Yokoyama M, Akita H, Matsushita K, Kurachi Y, Yamada M. Tertiapin potently and selectively blocks muscarinic K(+) channels in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293(1):196–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seko T, Kato M, Kohno H, et al. Structure-activity study of L-cysteine-based N-type calcium channel blockers: optimization of N- and C-terminal substituents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12(6):915–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tallent M, Liapakis G, O'Carroll AM, Lolait SJ, Dichter M, Reisine T. Somatostatin receptor subtypes SSTR2 and SSTR5 couple negatively to an L-type Ca2+ current in the pituitary cell line AtT-20. Neuroscience. 1996;71(4):1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xie J, Nagle GT, Childs GV, Ritchie AK. Expression of the L-type Ca(2+) channel in AtT-20 cells is regulated by cyclic AMP. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farrell SR, Rankin DR, Brecha NC, Barnes S. Somatostatin receptor subtype 4 modulates L-type calcium channels via Gβγ and PKC signaling in rat retinal ganglion cells. Channels (Austin). 2014;8(6):519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fujii Y, Gonoi T, Yamada Y, Chihara K, Inagaki N, Seino S. Somatostatin receptor subtype SSTR2 mediates the inhibition of high-voltage-activated calcium channels by somatostatin and its analogue SMS 201–995. FEBS Lett. 1994;355(2):117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neusch C, Bohme V, Riesland N, Althaus M, Moser A. The dopamine D2 receptor agonist α-dihydroergocryptine modulates voltage-gated sodium channels in the rat caudate-putamen. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2000;107(5):531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yasumoto F, Negishi T, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, Kuroda Y, Yoshikawa Y. Dopamine receptor 2 regulates L-type voltage-gated calcium channel in primary cultured mouse midbrain neural network. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2004;24(6):877–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mackie K, Lai Y, Westenbroek R, Mitchell R. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in AtT20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1995;15(10):6552–6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huang CL, Slesinger PA, Casey PJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Evidence that direct binding of G β γ to the GIRK1 G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel is important for channel activation. Neuron. 1995;15(5):1133–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sreenivasan VK, Stremovskiy OA, Kelf TA, et al. Pharmacological characterization of a recombinant, fluorescent somatostatin receptor agonist. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22(9):1768–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cawston EE, Redmond WJ, Breen CM, Grimsey NL, Connor M, Glass M. Real-time characterization of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) allosteric modulators reveals novel mechanism of action. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170(4):893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fusco A, Gunz G, Jaquet P, et al. Somatostatinergic ligands in dopamine-sensitive and -resistant prolactinomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158(5):595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Florio T, Barbieri F, Spaziante R, et al. Efficacy of a dopamine-somatostatin chimeric molecule, BIM-23A760, in the control of cell growth from primary cultures of human non-functioning pituitary adenomas: a multi-center study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(2):583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Córdoba-Chacón J, Gahete MD, Castaño JP, Kineman RD, Luque RM. Somatostatin and its receptors contribute in a tissue-specific manner to the sex-dependent metabolic (fed/fasting) control of growth hormone axis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(1):E46–E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Donangelo I, Melmed S. Treatment of acromegaly: future. Endocrine. 2005;28(1):123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gatto F, Feelders RA, van der Pas R, et al. Immunoreactivity score using an anti-sst2A receptor monoclonal antibody strongly predicts the biochemical response to adjuvant treatment with somatostatin analogs in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):E66–E71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oberg KE, Reubi JC, Kwekkeboom DJ, Krenning EP. Role of somatostatins in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor development and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):742–753, 753.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ben-Shlomo A, Schmid H, Wawrowsky K, et al. Differential ligand-mediated pituitary somatostatin receptor subtype signaling: implications for corticotroph tumor therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(11):4342–4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Feelders RA, de Herder WW, Neggers SJ, van der Lely AJ, Hofland LJ. Pasireotide, a multi-somatostatin receptor ligand with potential efficacy for treatment of pituitary and neuroendocrine tumors. Drugs Today (Barc). 2013;49(2):89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ma P, Wang Y, van der Hoek J, et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic comparison of a novel multiligand somatostatin analog, SOM230, with octreotide in patients with acromegaly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(1):69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lesche S, Lehmann D, Nagel F, Schmid HA, Schulz S. Differential effects of octreotide and pasireotide on somatostatin receptor internalization and trafficking in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):654–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ferone D, Gatto F, Arvigo M, et al. The clinical-molecular interface of somatostatin, dopamine and their receptors in pituitary pathophysiology. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;42(5):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shimon I, Rubinek T, Hadani M, Alhadef N. PTR-3173 (somatoprim), a novel somatostatin analog with affinity for somatostatin receptors 2, 4 and 5 is a potent inhibitor of human GH secretion. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004;27(8):721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Plöckinger U, Hoffmann U, Geese M, et al. DG3173 (somatoprim), a unique somatostatin receptor subtypes 2-, 4- and 5-selective analogue, effectively reduces GH secretion in human GH-secreting pituitary adenomas even in octreotide non-responsive tumours. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166(2):223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gillam MP, Molitch ME, Lombardi G, Colao A. Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(5):485–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]