Abstract

Anthropogenic noise is a global pollutant, affecting animals across taxa. However, how noise pollution affects resource acquisition is unknown. Hermit crabs (Pagurus bernhardus) engage in detailed assessment and decision-making when selecting a critical resource, their shell; this is crucial as individuals in poor shells suffer lower reproductive success and higher mortality. We experimentally exposed hermit crabs to anthropogenic noise during shell selection. When exposed to noise, crabs approached the shell faster, spent less time investigating it, and entered it faster. Our results demonstrate that changes in the acoustic environment affect the behaviour of hermit crabs by modifying the selection process of a vital resource. This is all the more remarkable given that the known cues used in shell selection involve chemical, visual and tactile sensory channels. Thus, our study provides rare evidence for a cross-modal impact of noise pollution.

Keywords: anthropogenic noise, assessment, attention, invertebrate, resource acquisition

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic noise is omnipresent in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats and has become a global pollutant affecting species across the phylogenetic tree (e.g. [1,2]). However, our understanding of how novel selection pressures, such as anthropogenic noise, affect animals' ability to assess vital resources is unknown.

Across the animal kingdom, the assessment of resources, such as territories, mates and food, is of critical importance, with cues used that correlate with expected gains in fitness, and result in adaptive motivational change [3,4]. Human-induced environmental changes may affect the ability of individuals to gather all the information necessary to assess vital resources.

Hermit crabs engage in a complex assessment process when selecting a vital resource, their shell, which provides protection from predators, desiccation, and extremes of salinity [5]. The assessment crabs carry out on shells involves information-processing and decision-making, occurring in discrete stages [6]. Thus, relevant information must be filtered from the environment, a process known as attention [7]. Shell selection requires sustained attention to make a decision, as the quality of the chosen shell has direct fitness consequences for the individual [6,8]. If species rely on perceiving information to assess vital resources, changes in the acoustic environment through noise pollution could have far-reaching consequences by affecting fitness-relevant information-gathering and decision-making.

Here we test whether anthropogenic noise affects the acquisition of a vital resource. Noise pollution research has focused primarily on species that use acoustic signals. However, there is some evidence that invertebrates that do not rely on acoustic signals are also affected by noise [9]. Sound consists of two components: particle motion and sound pressure, both of which can provide information to individuals [10]. Decapods, such as hermit crabs, appear to perceive particle motion only, but are capable of perceiving sound within the range of those produced by anthropogenic activities [11,12]. Using playback experiments, we manipulated the acoustic environment of hermit crabs by exposing them to either anthropogenic noise, or a control during shell selection. We predicted that individuals exposed to noise would adjust their assessment and decision-making processes in response to changes in the acoustic environment.

2. Material and methods

Hermit crabs (Pagurus bernhardus) were collected from rock pools and removed from their shells using a bench-vice (for details see electronic supplementary material). To ensure standardized high levels of motivation for shell acquisition, we provided individuals with a non-preferred Gibbula cineraria shell, 50% of the weight of each individual's relative ideal shell weight [5].

To create different acoustic environments, the experiment consisted of one of two 30 min treatments: anthropogenic noise, or a control (for details see electronic supplementary material and figure S1). A crystallizing dish, 17 cm in diameter, was used as an arena. Before each trial the arena was filled with fresh, 12°C seawater to a depth of 7.5 cm. Crabs were randomly assigned to either the control (N = 31) or the noise (N = 33) treatment. Each subject's ideal shell of relatively preferred weight and species (Littorina obtusata) [5] was placed on one randomly allocated side of the arena and the focal individual on the other.

To allow crabs to recover from handling, they were held within an upturned glass container for 5 min prior to the start of the treatment, following which the glass was removed, the playback started and the trial began. A trial ended when an individual either moved away in the new 100% shell, or having rejected it, remained in the 50% shell [3]. If crabs did not investigate the shell, or make a decision, the trial was ended after 30 min. We measured the following response variables: (i) latency to contact shell (s), (ii) investigation (s), i.e. time shell is investigated before abandoning 50% shell and entering 100%, or aborting further shell investigation, (iii) latency to enter shell (s), i.e. total time from the start of the experiment to leaving the 50% shell, (iv) final decision (yes/no), i.e. reject or accept 100% shell, and (v) latency to final decision (s). In four cases crabs did not investigate the offered 100% shell within 30 min [3,13] and were thus excluded from further analysis.

Since data did not fulfil the assumptions of parametric tests we used Mann–Whitney U tests throughout, unless stated otherwise. Sixty-four individuals were included in all analyses, with the exception of ‘latency to enter shell’, where 10 individuals who did not enter the presented 100% shell could not be included. All analyses were carried out in RStudio v. 0.99 [14]; data are available as electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

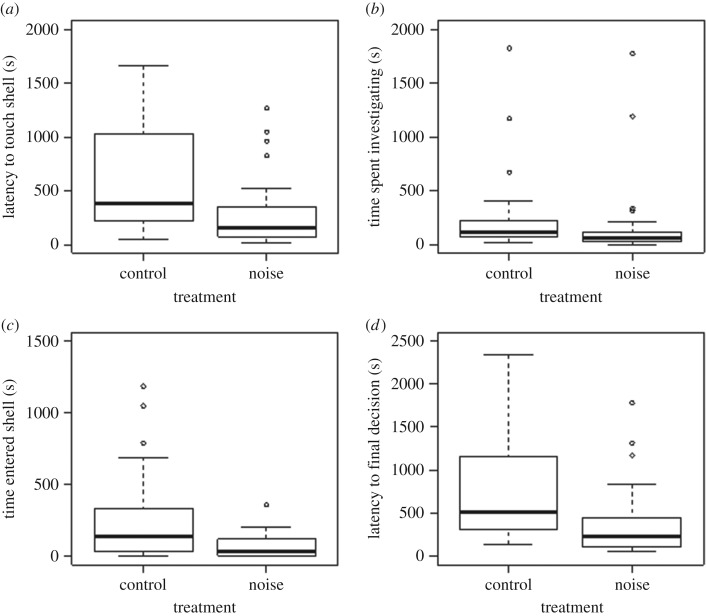

Latency to shell contact was shorter during noise than in the control exposure (NNoise = 33, NControl = 31, U = 749, p ≤ 0.001; figure 1a). Crabs exposed to noise also spent less time investigating shells than those exposed to the silent control (NNoise = 33, NControl = 31, U = 710, p = 0.0076; figure 1b). The time it took crabs to enter the preferred shell was shorter during noise than during the control playback (NNoise = 25, NControl = 29, U = 530, p = 0.0036; figure 1c). Latency to final decision was shorter during the noise than during the control playback (NNoise = 33, NControl = 31, U = 730, p = 0.003; figure 1d). Out of the 31 crabs in the control treatment, 28 took the optimal shell, i.e. made the ‘correct’ choice, whereas out of the 33 crabs in the noise treatment, only 24 took the optimal shell (chi-squared test:  , p = 0.071).

, p = 0.071).

Figure 1.

The effect of noise on resource assessment in hermit crabs at different stages of shell selection (median and interquartile range): (a) latency to touch the preferred shell, (b) time spent investigating preferred shell, (c) time entered preferred shell and (d) latency to final decision.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that anthropogenic noise alters an animal's assessment of a vital resource. Experimental exposure to noise shortened the shell assessment process, with crabs approaching the shell faster, spending less time investigating it, and entering it faster. When exposed to noise, crabs approached the shell faster, spent less time investigating it, and entered it faster. Thus, the changed acoustic environment had a clear effect on the behaviour of hermit crabs.

It is interesting to note that noise affected hermit crabs across sensory modalities; thus our study provides rare evidence for a cross-modal impact of noise pollution [9,15]. Hermit crabs use chemical, visual and tactile information to assess shells [5,16,17]. As changes in the acoustic environment do not affect any of these sensory modalities directly, it is unlikely that the differences in behaviour between the two treatments result from direct influences on these sensory channels.

There are several non-mutually exclusive hypotheses regarding how noise may affect assessment and thereby shorten the shell selection process: noise may affect cognitive processing [18], cause stress [19], and/or mask sound [20], all of which could affect shell selection simultaneously. However, as an empty gastropod shell does not emit sound per se, masking by noise would likely have no effect on shell selection. In contrast, changes in the acoustic environment may affect attention, as individuals can only process a finite amount of information simultaneously [21].

During the assessment of a new shell, individuals have to divide their attention between at least two different processes: the assessment of the shell and vigilance for potential predators, as individuals are highly vulnerable during shell exchange [5]. Thus, a novel stimulus such as noise may force individuals to reallocate their attention [22]. Such reallocation of an individual's finite attention has been demonstrated in Caribbean hermit crabs when responding to an approaching threat [23]. Our results are also consistent with noise increasing motivation [8] to gain the resource. For example, individuals may be interpreting noise as a threatening stimulus, such as a predator [24], increasing their motivation to gain a shell offering increased protection.

Generally, care must be taken when extrapolating results from short-term tank-based experiments to meaningful implications for individuals living in the wild, because underwater acoustics are complex (e.g. [25,26]) and noise levels in tanks may be higher than those experienced in nature. However, experimental studies in a controlled environment provide a starting point to examine effects of anthropogenic noise, which have only recently been acknowledged, paving the way for future studies in real world scenarios. Moreover, in the marine environment noise is often chronic [27] and it remains to be investigated whether species can habituate and become tolerant to repeated, or chronic noise exposure. More broadly, theoretical simulations have demonstrated that noise does not necessarily impair information assessment [28] and could offer a source of public information for eavesdroppers [29]. Responses to anthropogenic noise are complex [24], depending on the biology of the species. The extent to which these responses impact fitness, either positively or negatively, remains to be understood.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that changes in the acoustic environment affect the acquisition of a fitness determining resource, as survival, growth, and reproduction of hermit crabs depend on the occupancy of shells of appropriate size and shape (e.g. [30]). Notably, despite the known cues used in shell selection not being directly affected by changes in the acoustic environment, noise still affects a fitness-relevant process, offering an example of a cross-modal impact. Moreover, this work contributes to the small, but increasing body of evidence that it is not only vertebrates which are affected by noise, but also invertebrates [31].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gillian Riddell, Mary Friel and Irene Voellmy for their help, and Mark Laidre and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Ethics

There are no legal requirements for studies involving decapod crustaceans in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, but we followed the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research.

Data accessibility

Data are available at Dryad Digital Repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.g1hk2 [32].

Authors' contributions

E.P.W., G.A. and H.P.K. conceived and designed the study; E.P.W. collected the data; all authors analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the Northern Ireland Department for Employment and Learning (DEL).

References

- 1.Shannon G, et al. 2015. A synthesis of two decades of research documenting the effects of noise on wildlife. Biol. Rev. 91, 982–1005. ( 10.1111/brv.12207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunc HP, McLaughlin KE, Schmidt R. 2016. Aquatic noise pollution: implications for individuals, populations, and ecosystems. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160839 ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.0839) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson N, Elwood R. 1989. How animals make assessments—information gathering by the hermit crab Pagurus bernhardus. Anim. Behav. 38, 951–957. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(89)80136-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker GA, Stuart RA. 1976. Animal behavior as a strategy optimizer: evolution of resource assessment strategies and optimal emigration thresholds. Am. Nat. 110, 1055–1076. ( 10.1086/283126) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwood RW, Neil SJ. 1992. Assessments and decisions: a study of information gathering by hermit crabs. London, UK: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwood R. 1995. Motivational change during resource assessment by hermit crabs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 193, 41–55. ( 10.1016/0022-0981(95)00109-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendl M. 1999. Performing under pressure: stress and cognitive function. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 65, 221–244. ( 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00088-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vance R. 1972. Role of shell adequacy in behavioral interactions involving hermit crabs. Ecology 53, 1075–1083. ( 10.2307/1935419) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunc HP, Lyons GN, Sigwart JD, McLaughlin KE, Houghton JDR. 2014. Anthropogenic noise affects behavior across sensory modalities. Am. Nat. 184, E93–E100. ( 10.1086/677545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radford CA, Montgomery JC, Caiger P, Higgs DM. 2012. Pressure and particle motion detection thresholds in fish: a re-examination of salient auditory cues in teleosts. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 3429–3435. ( 10.1242/jeb.073320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popper AN, Salmon M, Horch KW. 2001. Acoustic detection and communication by decapod crustaceans. J. Comp. Physiol. A 187, 83–89. ( 10.1007/s003590100184) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts L, Cheesman S, Elliott M, Breithaupt T. 2016. Sensitivity of Pagurus bernhardus (L.) to substrate-borne vibration and anthropogenic noise. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 474, 185–194. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2015.09.014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwood RWE, Stewart A. 1985. The timing of decisions during shell investigation by the hermit crab, Pagurus bernhardus. Anim. Behav. 33, 620–627. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80086-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.RStudio Team. 2015. RStudio: integrated development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris-Drake A, Kern JM, Radford AN. 2016. Cross-modal impacts of anthropogenic noise on information use. Curr. Biol. 26, R911–R912. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.064) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazlett B. 1996. Comparative study of hermit crab responses to shell-related chemical cues. J. Chem. Ecol. 22, 2317–2329. ( 10.1007/BF02029549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazlett B. 1996. Organisation of hermit crab behaviour: responses to multiple chemical inputs. Behaviour 133, 619–642. ( 10.1163/156853996X00242) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan AAY, Blumstein DT. 2011. Attention, noise, and implications for wildlife conservation and management. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 131, 1–7. ( 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.01.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kight CR, Swaddle JP. 2011. How and why environmental noise impacts animals: an integrative, mechanistic review. Ecol. Lett. 14, 1052–1061. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01664.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brumm H, Slabbekoorn H. 2005. Acoustic communication in noise. Adv. Study Behav. 35, 151–209. ( 10.1016/S0065-3454(05)35004-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dukas R. 2004. Causes and consequences of limited attention. Brain Behav. Evol. 63, 197–210. ( 10.1159/000076781) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washburn DA, Taglialatela LA. 2006. Attention as it is manifest across species. In Comparative cognition: experimental explorations of animals intelligence (eds Wasserman EA, Zentall TR), pp. 127–142. Oxford, UK and New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan AAY, Giraldo-Perez P, Smith S, Blumstein DT. 2010. Anthropogenic noise affects risk assessment and attention: the distracted prey hypothesis. Biol. Lett. 6, 458–461. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2009.1081) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon G, Crooks KR, Wittemyer G, Fristrup KM, Angeloni LM. 2016. Road noise causes earlier predator detection and flight response in a free-ranging mammal. Behav. Ecol. 27, 1370–1375. ( 10.1093/beheco/arw058) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruintjes R, Radford AN. 2013. Context-dependent impacts of anthropogenic noise on individual and social behaviour in a cooperatively breeding fish. Anim. Behav. 85, 1343–1349. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wale MA, Simpson SD, Radford AN. 2013. Size-dependent physiological responses of shore crabs to single and repeated playback of ship noise. Biol. Lett. 9, 20121194 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.1194) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slabbekoorn H, Bouton N, van Opzeelad I, Coers A, Ten Cate C, Popper AN. 2010. A noisy spring: the impact of globally rising underwater sound levels on fish. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 419–427. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2010.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laidre ME, Lamb A, Shultz S, Olsen M. 2013. Making sense of information in noisy networks: human communication, gossip, and distortion. J. Theor. Biol. 317, 152–160. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.09.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laidre ME. 2013. Eavesdropping foragers use level of collective commotion as public information to target high quality patches. Oikos 122, 1505–1511. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00188.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tricarico E, Gherardi F. 2007. Resource assessment in hermit crabs: the worth of their own shell. Behav. Ecol. 18, 615–620. ( 10.1093/beheco/arm019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morley EL, Jones G, Radford AN. 2013. The importance of invertebrates when considering the impacts of anthropogenic noise. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20132683 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2683) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh EP, Arnott G, Kunc HP. 2017. Data from: Noise affects resource assessment in an invertebrate. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.g1hk2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Walsh EP, Arnott G, Kunc HP. 2017. Data from: Noise affects resource assessment in an invertebrate. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.g1hk2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at Dryad Digital Repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.g1hk2 [32].