Under the Paris Agreement of the UN's 21st Conference of the Parties, over 100 nations signed up to the goal of keeping future warming within 2°C of pre-industrial levels, and ideally below 1.5°C. Yet anthropogenic CO2 emissions, mainly from combustion of fossil fuels, are now the highest they have been in human history, and 30% higher than 1990 [1]. Accumulation of CO2 and other human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has already driven global warming of approximately 1°C. If warming continues at the current rate, the aspirational target of 1.5°C will be out of reach within 30 years.

The urgent need for developing methods to extract CO2 from air (so-called negative emission technologies, NETs) that are safe and affordable, and that can be scaled-up to augment efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, is becoming increasingly well recognized and understood (e.g. [2]). Indeed, extensive modelling scenarios assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that give us more than a 50% chance of limiting warming to less than 2°C assume substantial CO2 extraction is achievable with bioenergy crops in combination with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) in the second half the 21st Century [3]. However, major assumptions about land availability, feasibility at scale, and costs involved raise doubt about the promise and effectiveness of BECCS [4,5].

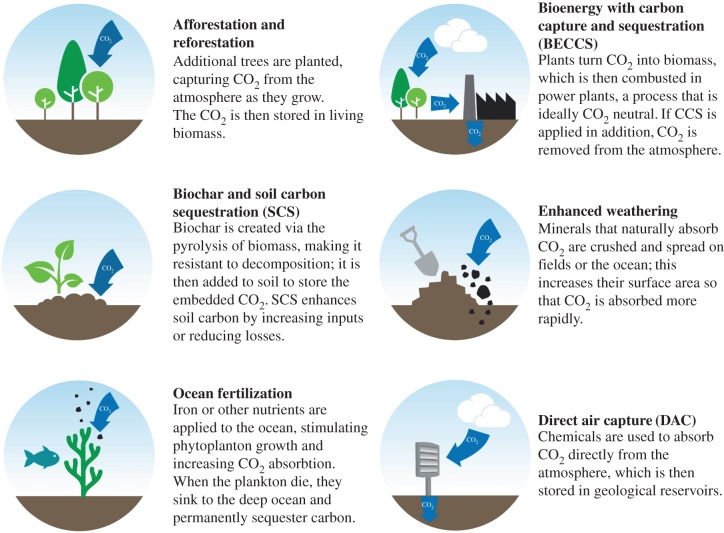

A range of potential techniques for extracting CO2 from the atmosphere is being investigated that afford opportunities for mitigating and ameliorating climate change (figure 1), each of which also needs to be understood in terms of feasibility, cost and acceptability [6,7]. The papers in this mini-series address an underdeveloped NET, enhanced rock weathering, with a particular focus on croplands managed for food production and bioenergy. Weathering is a slow natural process removing CO2 from the atmosphere on long timescales of a million years or more. During weathering, silicate rocks are chemically broken down to release base cations and generate bicarbonate, which is ultimately transferred to the oceans leading to carbonate precipitation on the seafloor. These processes can be accelerated by amending soils with crushed calcium and magnesium-bearing silicate rocks with a high reactive surface area to deliver effective carbon sequestration in soils and the oceans [8,9]. Enhanced weathering is also co-deployable with forestry and crops used in BECCS, enhancing its carbon sequestration potential and reducing costs. Reduced atmospheric CO2, in combination with the production of soluble alkalinity from weathered rocks, can help reduce ocean acidification to protect coral reefs and marine fisheries [8,9].

Figure 1.

Six common categories of negative emissions strategies for extracting CO2 from the atmosphere. Reproduced with permission from [7].

Kantola et al. [10] deal with the opportunities presented by row crop agricultural production of food and bioenergy crops for enhancing rock weathering. They highlight mechanisms by which enhanced weathering on agricultural lands could combat soil acidification and nitrogen loss while providing plant-essential nutrients, two negative consequences of intensive cropland farming. Uncertainties in the long-term effects on soils and crops remain and can only be addressed through long-term experiments and field trials investigating feasibility and effectiveness. Nevertheless, with nearly 11% of the terrestrial surface intensively managed for crop production, enhanced weathering could offer an opportunity to employ these soils to sequester atmospheric carbon at scale within a decade or two, while benefitting crop production. Additionally, this would use land already in production, thereby avoiding potential land use conflicts.

Edwards et al. [11] provide a complementary tropical cropland perspective, focusing on the potential for deployment of enhanced weathering across over 680 million hectares of tropical agriculture, with the warm climates and productive crops substantially accelerating weathering. They identify potential co-benefits including decreased soil acidification, reduced heavy metal toxicity and increased phosphorus-supply of highly weathered nutrient-poor tropical soils promoting higher crop yields. This may have the effect of sparing forest for conservation, and reducing cultural eutrophication. Recycling the substantial annual global production of silicate waste resulting from human activities [12] would minimize the impacts of mining operations on the environment, including deforestation, and reduce energy requirements for crushing and transporting silicates. Negative consequences identified [11] include erosion of silicates into rivers and coral reefs that might increase inorganic turbidity, sedimentation and pH, with unknown impacts for biodiversity. They conclude by outlining a research agenda for responsibly unlocking the potential of the tropics for carbon capture by enhanced weathering, including assessment of the potential impacts on human health, farmland, forest, stream-water chemistry and biodiversity.

Questions concerning the spatial scale of roll-out necessary to affect atmospheric CO2, climate and ocean chemistry on decadal to century timescales can only be addressed through Earth system modelling [8,9]. Central to these large-scale Earth system issues are robust numerical models describing the geochemical weathering of crushed silicates by climate in combination with the rooting systems of crop plants and their associated soil microbes. In this context, Taylor et al. [13] review how current models represent the geochemical processes describing the soil weathering CO2 sink. They highlight the need to bridge the gap between the current generation of weathering models that typically neglect agricultural processes and agricultural models simulating how land management practices govern cropland soil chemistry and greenhouse gas emissions that neglect weathering. Land use history and fertilizers are key drivers of the physico-chemical characteristics of agricultural soils, including pH. Capturing these interactions with crushed silicates will be an important development of soil weathering models if they are to provide powerful and flexible research tools for assessment of rates of enhanced weathering, nutrient release, pH change and carbon capture.

Meysman & Montserrat [14] shift the focus to the marine realm by considering the potential for carbon capture by applying crushed silicates directly into coastal environments. The idea is that deliberately introducing fast-weathering silicate minerals onto coastal sediments releases alkalinity into the overlying waters, thus creating a coastal CO2 sink. As they point out, the concept is still at an early stage and dedicated experiments need to (i) better constrain the weathering rate under in situ conditions, and (ii) evaluate ecosystem impacts arising from the liberation of weathered chemical products.

Ultimately, the public perception of any NET option may prove to be as important as the underlying scientific evidence that builds the case for deployment to combat climate change. If policymakers and governments propose deployment, there has to public trust and acceptance of the technology involved. Social science engagement is therefore critical to understanding how society will perceive different NET options [15]. How might public groups in the UK, North America and non-western countries, respond to and perceive potential risks and benefits of possible enhanced weathering strategies as innovative responses to the climate change problem? Pidgeon & Spence [16] report the first UK-wide assessment of the public's social perception of enhanced terrestrial weathering. Their analyses provide an important baseline for determining how this may change as the technology gains prominence and for comparing the UK public with other parts of the world. Encouragingly, it appears the public generally agree that scientists should be able to conduct small-scale trials into enhanced weathering, provided there is scientific independence, strict monitoring, risk minimization and transparency of results.

Lawford-Smith & Currie [17] address some of the thorny ethical issues associated with developing negative emissions options. They analyse the well-rehearsed moral hazard argument in relation to questions of blame and responsibility for removing the onus on developed countries to reduce fossil fuel emissions. Would large-scale effective NETs deployed in the future lead to less mitigation today [18]? Might, for example, it encourage society to think CO2 emissions can exceed ‘safe’ limits in the near-term with the promise that excess carbon will pulled out of the atmosphere later? Given current lack of depth in our understanding of the effectiveness of NETs, a safer working assumption might be that they may not be deployable this century, forcing the urgency of deeper near-term emission cuts to avoid locking in the worst effects of future climate change.

Collectively, the papers in this mini-series suggest that enhanced weathering has promise in providing climate and food security by capturing carbon and improving crop yields, while decreasing fertilizer and pesticide usage and costs. The collection is not in any way intended to be a comprehensive treatment of the topic but rather to represent an introduction to some of the key issues with an emphasis on biological interactions; detailed treatment of enhanced weathering is given elsewhere [19]. The topic is, however, the focus of the newly established international Leverhulme Centre for Climate Change Mitigation (http://www.lc3m.org/). The new Centre aims to deliver transformative understanding of all aspects of enhanced weathering with croplands as a strategic NET, including its technical, environmental, economic and social viability, as highlighted in a recent Nature Geoscience editorial [20]. It aims to revolutionize climate change mitigation by linking it to the substantive co-benefit of delivering resource-efficient sustainable food security. Moving towards these goals will require fundamentally understanding our ability to manipulate food/bioenergy production systems to drive biogeochemical cycles that positively affect global CO2, climate and ocean chemistry—a formidable challenge that underpins some climate change mitigation strategies required by the Paris Agreement.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank the authors for submitting their manuscripts and reviewers for returning prompt, helpful and critical comments. I am very grateful to Rick Battarbee and Robert Elwood for their support of this mini-series topic and thank Surayya Johar and Raminder Shergill for patient and efficient editorial handling of the manuscripts, and the Editorial Board of Biology Letters for handling the reviewing of several submissions. I gratefully acknowledge funding by the Leverhulme Trust through a Leverhulme Research Centre award (RC-2015-029).

Competing interests

I declare I have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by Leverhulme Trust (RC-2015-029).

References

- 1.Le Quere C, et al. 2016. Global carbon budget 2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 605–649. ( 10.5194/essd-8-605-2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council. 2015. Climate intervention. Carbon dioxide removal and reliable sequestration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds O Edenhofer et al.) New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuss SF, et al. 2014. Betting on negative emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 850–853. ( 10.1038/nclimate2392) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson K. 2015. Talks in the city of light generate more heat. Nature 528, 437 ( 10.1038/528437a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith P, et al. 2016. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50. ( 10.1038/nclimate2870) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minx JC, Lamb WF, Callaghan MW, Bornmann L, Fuss S. 2017. Fast growing research on negative emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 035007 ( 10.1088/1748-9326/aa5ee5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köhler P, Hartmann J, Wolf-Gladrow DA. 2010. Geoengineering potential of artificially enhanced silicate weathering of olivine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20 228–20 233. ( 10.1073/pnas.1000545107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor LL, et al. 2016. Enhanced weathering strategies for stabilizing climate and averting ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 402–406. ( 10.1038/nclimate2882) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantola IB, Masters MD, Beerling DJ, Long SP, DeLucia EH. 2017. Potential of global croplands and bioenergy crops for climate change mitigation through deployment for enhanced weathering. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160714 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0714) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards DP, Lim F, James RH, Pearce CR, Scholes J, Freckleton RP, Beerling DJ. 2017. Climate change mitigation: potential benefits and pitfalls of enhanced rock weathering in tropical agriculture. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160715 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0715) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renforth P, Washbourne CL, Taylder J, Manning DAC. 2011. Silicate production and availability for mineral carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 2035–2041. ( 10.1021/es103241w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor LL, Beerling DJ, Quegan S, Banwart SA. 2017. Simulating carbon capture by enhanced weathering with croplands: an overview of key processes highlighting areas of future model development. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160868 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0868) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meysman FJR, Montserrat F. 2017. Negative CO2 emissions via enhanced silicate weathering in coastal environments. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160905 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright MJ, Teagle DAH, Feetham PM. 2014. A quantitative evaluation of the public response to climate engineering. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 106–110. ( 10.1038/nclimate2087) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pidgeon NF, Spence E. 2017. Perceptions of enhanced weathering as a biological negative emissions option. Biol. Lett. 13, 20170024 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawford-Smith H, Currie A. 2017. Accelerating the carbon cycle: the ethics of enhanced weathering. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160859 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0859) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson K, Peters G. 2016. The trouble with negative emissions. Science 354, 182–183. ( 10.1126/science.aah4567) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann J, West AJ, Renforth P, Köhler P, La Rocha CLD, Wolf-Gladrow DA, Dürr HH, Scheffran J. 2013. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Rev. Geophys. 51, 113–149. ( 10.1002/rog.20004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anon. 2016. A step up for geoengineering [editorial]. Nat. Geosci. 9, 855 ( 10.1038/ngeo2858) [DOI] [Google Scholar]