Abstract

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a severe and rapid liver injury, often occurring without any preexisting liver disease, which may precipitate multiorgan failure and death. ALF is often associated with impaired β-oxidation and increased oxidative stress (OS), characterized by elevated levels of hepatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO) products. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α has been shown to confer hepatoprotection in acute and chronic liver injury, at least in part, related to its ability to control peroxisomal and mitochondrial β-oxidation. To study the pathophysiological role of PPARα in hepatic response to high OS, we induced a pronounced LPO by treating wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice with high doses of fish oil (FO), containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. FO feeding of Pparα-deficient mice, in contrast to control sunflower oil, surprisingly induced coma and death due to ALF as indicated by elevated serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, ammonia, and a liver-specific increase of ROS and LPO-derived malondialdehyde. Reconstitution of PPARα specifically in the liver using adeno-associated serotype 8 virus-PPARα in Pparα-deficient mice restored β-oxidation and ketogenesis and protected mice from FO-induced lipotoxicity and death. Interestingly, administration of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate prevented FO-induced ALF in Pparα-deficient mice, and normalized liver ROS and malondialdehyde levels. Therefore, PPARα protects the liver from FO-induced OS through its regulatory actions on ketone body levels. β-Hydroxybutyrate treatment could thus be an option to prevent LPO-induced liver damage.

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a severe liver injury often occurring in the absence of preexisting liver disease, which leads to impaired hepatic functions, encephalopathy, and multiple-organ failure (1). Clinical manifestations of ALF are usually abnormal biochemical parameters of liver function such as hypoglycemia, hypoketonemia, lactic acidosis, coagulopathy, and hyperammonemia, which may rapidly result in agitation and coma (1, 2). The predominant cause of ALF, beside viral infections with hepatitis A, B, and E viruses, is drug-induced liver injury, as exemplified by ALF induced by acetaminophen (APAP), a commonly used analgesic and antipyretic agent (3).

Evidence has emerged that oxidative stress (OS) and redox imbalance are triggering factors of ALF, often linked to depressed mitochondrial function, impaired fatty acid (FA) oxidation (FAO) and loss of ATP (4, 5). N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone-imine, an intermediate metabolite of APAP, binds to mitochondrial proteins, leading to hepatic OS and further mitochondrial swelling and pore opening (6). In Reye's syndrome and acute fatty liver of pregnancy, which are related to inherited deficiencies of FAO enzymes such as mitochondrial long-chain acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenase (LCAD), carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT)1 and CPT2 and very-LCAD (VLCAD), defects in FA transport and oxidation increase OS and lipid peroxidation (LPO), leading to accumulation of toxic FA metabolites, such as malondialdehyde (MDA), in placenta and serum of acute fatty liver of pregnancy patients, provoking maternal liver damage (7–9).

Treatment of ALF is related to its etiology and comprises metabolic and nutritional support or liver transplantation, depending on the stage and degree of liver injury (1). N-acetylcysteine is a clinically used antioxidant agent preventing APAP-induced liver injury by providing substrates for glutathione synthesis, which scavenges free radicals from N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone-imine, generated during APAP metabolism (10). Similarly, manganese (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin chloride, a superoxide dismutase mimetic, neutralizes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thus improving survival time in a murine model of APAP-induced ALF (11).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α (PPARα/NR1C1), is a ligand-activated nuclear receptor controlling the transcription of genes related to peroxisomal and mitochondrial β-oxidation, FA transport and ketogenesis in different nutritional states (12, 13). Natural PPARα agonists are FA derivatives and polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) such as n-3 docosahexaenoic (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (14, 15). PPARα has been shown to exert hepatoprotective effects in a range of liver pathologies associated with OS and LPO, such as alcohol-induced liver damage, dietary-induced steatohepatitis, and drug-induced liver failure (16–18). The beneficial activities of PPARα stem from its ability to improve mitochondrial oxidation, neutralize ROS, and induce enzymes involved in the detoxification of aldehydes generated by alcohol metabolism and LPO (19, 20). Pparα-deficient mice reveal decreased hepatic expression of genes related to FAO and ketogenesis, leading to aggravated steatohepatitis in mice fed a high saturated-fat diet and an inability to maintain ketone body levels during fasting (13, 21–23).

Fish oils (FOs) enhance hepatic β-oxidation capacity by activating PPARα (24–26). However, in rodents, administration of pharmacological high-doses of FO, which are enriched in n-3 PUFA with high degree of unsaturation, modifies the antioxidant response, thus triggering hepatic OS and generation of toxic LPO products that form adducts with proteins and nucleic acids (27–30). Accordingly, FO fail to prevent steatohepatitis in mice fed a methionine and choline-deficient diet due to the increase of hepatic lipoperoxides, which provoke lipotoxic hepatocellular injury (31). Importantly, recent clinical studies show that FO do not lead to an improvement in the primary outcome of histological activity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients (32), which may be, at least in part, related to the decreased expression of PPARα with progressing stages of liver fibrosis and NASH (33).

To study the pathophysiological role of PPARα in the hepatic response to FA with a strong LPO potential, we established a murine model of acute hepatic OS by treating mice with high doses of FO. Contrary to control sunflower oil (SO) treatment, FO led to ALF and death of the Pparα-deficient, but not of wild-type, mice, a lethal effect related to a strong increase of OS and LPO products in mouse livers. We further show that liver-specific PPARα protects from FO-induced ALF by stimulating ketogenesis, thus preserving β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) levels. β-OHB treatment could thus constitute an option to prevent OS- and LPO-induced liver damage.

Materials and Methods

Animal experimentations

Animal studies were performed in compliance with European Community specifications regarding the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Nord-Pas de Calais Ethical Committee for animal use. Pparα-deficient mice (Sv/129 X C57BL/6N chimeras) were generated originally by inserting 1.14-kb Neo gene between PstI and SphI restriction sites present in exon 8 of Pparα gene encoding the ligand-binding domain as previously described (34). Ten-week-old females C57BL6/J wild-type and more than 10 generations C57BL/6J backcrossed Pparα-deficient mice were fed a standard chow diet. Body weight and food intake, monitored by weighing special gridded metal food containers at regular intervals, were recorded throughout the feeding period. The treatment with dietary oils was standardized on the basis of caloric content (isocaloric exchange) to keep the total FA content identical and varying hence only qualitatively the FA composition (29). Animals were treated twice a day (at 10 am and 5 pm) for either 4 or 12 days with SO or FO (both Sigma-Aldrich) by gavage (18 mg/g·d). The dose corresponding to a 10% FO diet was chosen experimentally on the basis of its OS-inducing capacity (35). SO contained 61% of n-6 PUFA, whereas FO contained 30% of n-3 PUFA with a EPA to DHA ratio of 1.2. For reconstitution of β-OHB levels, Pparα-deficient mice were ip injected with sodium DL-β-OHB (2.5 mg/g·d; Sigma-Aldrich) twice a day, directly after dietary oil gavage. The dose of β-OHB has been assessed experimentally in FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice to reach comparable β-OHB plasma levels as observed in wild-type mice upon FO treatment. PBS injection was used as a control. For dietary oil gavage and β-OHB injection mice were sacrificed at day 4, 30 minutes after second treatment. Organs and plasma samples were immediately collected for further analysis.

In vivo administration of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector

Eight-week-old Pparα-deficient mice were injected through the tail vein with adeno-associated serotype 8 virus (AAV8)-thyroxine-binding globulin (Tbg)-3xFLAG-PPARα vector (6 × 1011 genome copies per mouse) as previously described (36). Control Pparα-deficient mice received AAV8-TBG-LacZ expressing β-galactosidase (6 × 1011 genome copies per mouse). β-Galactosidase activity was assessed from frozen liver sections using LacZ Tissue Staining kit (Invivogene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hepatic FLAG-tagged PPARα expression was detected in lysates by western blot analysis with the anti-FLAGM2 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mice were subjected to the indicated treatment 2 weeks after AAV injection.

Assessment of OS and lipotoxicity

Frozen tissues (25 mg) were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150mM sodium chloride, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets [Roche]) and sonicated for 15 seconds with 50% amplitude on ice using a Vibra-Cell sonicator (Sonics&Materials). The tissue lysate was centrifuged at 1600g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was used for quantification of MDA (Cayman Chemicals) and ROS (Cell Biolabs), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total liver Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity was measured from 25 mg of frozen liver samples by using a Glutathione S-Transferase Assay kit (Cayman Chemicals), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Values were expressed as nanomoles of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene conjugated to reduced glutathione/min and normalized to total protein level as measured by using BC Protein Assay kit (Interchim) according to manufacturer's protocol using BSA as a standard.

mRNA analysis

Total RNA was prepared from frozen liver using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). After treatment with amplification-grade Deoxyribonuclease I (Thermo Scientific), 1 μg of RNA was used for reverse transcription with Superscript reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) and random hexamer primers. cDNA levels were measured by real-time quantitative PCR using Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green QRT-PCR Master Mix (Stratagene) on a Mx3005P detection system (Stratagene). Specific primers were used (Supplemental Table 1) and mRNA expression levels normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA using the 2 delta delta cycle threshold method.

Metabolite measurements

Plasma metabolites were measured with a Konelab 20 Clinical Chemistry Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc). Hepatic triglyceride (TG) levels were measured using TRIGL GPO/PAP reagent (Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions and normalized to total liver protein concentration assessed by using a BC Protein Assay kit (Interchim) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data, represented as mean ± SEM, were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software). Comparisons among experimental groups were performed with either t test or ANOVA as indicated in figure legends. Significant differences were subjected to the appropriate post hoc test as indicated in figure the legends. P < .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

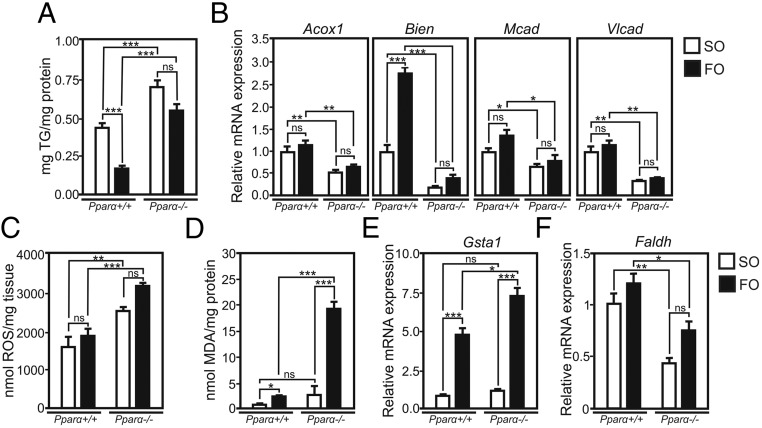

Pparα deficiency promotes the OS response induced by FO feeding

Treatment with high doses of PUFA has been associated with OS due to the presence of multiple double bonds between carbons, which increases the susceptibility to nonenzymatic oxidation (27–30). To study the role of PPARα in the hepatic response to LPO, we established a model of PUFA-induced OS. Wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice were gavaged with high doses of FO (containing α-linolenic acid, EPA, and DHA with 3, 5, and 6 cis-double bonds between carbons, respectively) or control SO (enriched in n-6 linoleic acid, which contains 2 cis-double bonds) during 4 days. The liver TG-lowering activities of FO in livers of wild-type mice were not observed in Pparα-deficient mice. Instead, hepatic TG accumulated in both SO- and FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice (Figure 1A), associated with lower expression of genes related to FAO, such as acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acox1), enoyl-CoA hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Bien), medium CAD and VLCAD (Mcad and Vlcad), whose expression levels are controlled by PPARα (Figure 1B) (37). The defective handling of PUFA led to an increase of liver ROS in both SO- and FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice, showing that Pparα ablation induces OS in response to dietary PUFA (Figure 1C). To assess the consequence of ROS elevation in Pparα deficiency on PUFA peroxidation, hepatic levels of lipotoxic MDA, a marker of LPO, were measured (38). MDA levels increased in wild-type (4.5-fold) and even more strongly (22-fold) in Pparα-deficient mice upon FO feeding, whereas treatment with SO only slightly increased liver MDA (Figure 1D). MDA levels did not change in brain, kidney and heart of FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice (Supplemental Figure 1), suggesting that FO treatment leads to a liver-specific MDA increase, likely due to impaired clearance and increased peroxidation of free FA remnants entering the liver. Hepatic expression of glutathione S-transferase α1 (Gsta1), the most abundantly expressed GST in the liver accounting for the metabolism of most of peroxidation-derived aldehydes in response to LPO and known to catalyze the conjugation of PUFA-derived aldehydes to reduced glutathione (39), was elevated upon FO compared with SO treatment in wild-type mice. This increase was even more pronounced in Pparα-deficient mice (Figure 1E). Total hepatic GST activity was also elevated in wild-type mice upon FO gavage compared with SO, whereas Pparα deficiency further increased GST activity only after SO but not FO (Supplemental Figure 2), indicating that a limit has been achieved in Pparα-deficient mice to further increase of the antioxidant capacity. Detoxification of aldehydes generated by LPO occurs also through the activity of fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase (Faldh), a PPARα target gene, which oxidizes long-chain aliphatic aldehydes to FA (20). The expression of hepatic Faldh was markedly decreased in both SO- and FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice as compared with wild-type mice, further illustrating the impaired LPO-derived aldehyde detoxification potential in the absence of PPARα (Figure 1F). Of note, wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice fed a normal chow diet displayed significant changes neither in hepatic TG levels (Supplemental Figure 3A), nor in liver ROS, MDA (Supplemental Figure 3, C and D), and Gsta1 mRNA levels (Supplemental Figure 3E). In line with previously published data (13, 20, 22), hepatic mRNA levels of FAO controlling genes Acox, Bien, Mcad, and Vlcad (Supplemental Figure 3B) as well as Faldh (Supplemental Figure 3F) were lower in Pparα-deficient mice as compared with wild-type mice. These results show that hepatic lipoperoxide accumulation increases with the degree of PUFA unsaturation and that PPARα modulates the hepatic response to PUFA and protects the liver from OS and LPO.

Figure 1. Impairment of FAO pathways potentiates FO-induced OS and LPO in Pparα-deficient mice.

A, Hepatic TG content in wild-type (WT) and Pparα-deficient mice (KO) gavaged with SO or FO. B, Hepatic expression of FAO genes. C, Hepatic ROS levels. D, Hepatic MDA levels. E and F, Hepatic gene expression of Gsta1 and Faldh. Gene expression values are shown relative to WT mice treated with SO (n = 10/group). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .005; by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

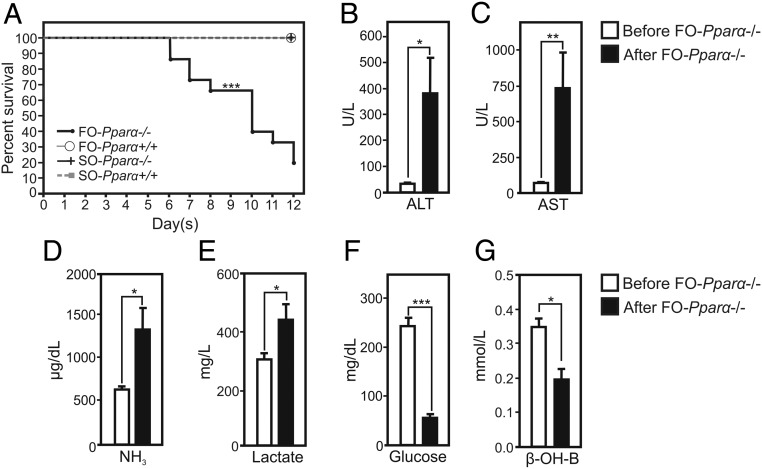

High-dose FO-induced OS leads to ALF and death in the absence of Pparα

We next determined the role of PPARα in the pathological response to long-term exposure to FO. Interestingly, FO treatment resulted in the rapid death of Pparα-deficient, but not wild-type, mice (Figure 2A). A total of 80% of Pparα-deficient mice died within 12 days of FO treatment, whereas SO-treated wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice remained in good condition. The death of FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice was preceded by an entry in coma. To assess whether the FO-induced coma was a result from ALF, plasma parameters were monitored in Pparα-deficient mice before treatment with FO, and when mice fell into coma (Figure 2, B–F). FO administration to Pparα-deficient mice strongly elevated plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (from 30 U/L before to 380 U/L after treatment) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (from 50 U/L to 745 U/L) levels, indicative of an acute liver insult (Figure 2, B and C). Serum ammonia levels, which correlate with the severity of hepatic encephalopathy (40), increased in FO-treated Pparα-deficient animals (from 550 to 1300 μg/dL) (Figure 2D). Moreover, plasma lactate levels, often measured for the prognosis of ALF (41), were elevated in FO-treated mice (Figure 2E), whereas glucose and ketone body β-OHB levels were decreased (Figure 2, F and G), indicating a failure of gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis concomitant with ALF (1). In contrast, a 4-day treatment of wild-type mice with FO has not elevated ALT and AST above its normal range in plasma (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B) (42), whereas ammonia levels were significantly elevated after FO treatment when compared with basal levels (Supplemental Figure 4C). Nevertheless, the increase of ammonia levels in plasma was not associated with impaired liver functions as hallmarked by unchanged plasma levels of lactate, glucose and the increase of β-OHB levels (Supplemental Figure 4, D–F). Altogether, these results show that the absence of PPARα leads to ALF and death of mice challenged with high doses of FO.

Figure 2. PPARα deficiency provokes ALF in mice gavaged with high-dose FO.

A, Kaplan-Meier curve of wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice treated with SO or FO (n = 15/group). B and C, Plasma levels of ALT and AST of Pparα-deficient mice before gavage with FO and FO-treated mice in coma (after FO) (n = 10/group). D–G, Plasma levels of ammonia (NH3), lactate, glucose, and β-OHB (n = 10/group); *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .005; by paired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

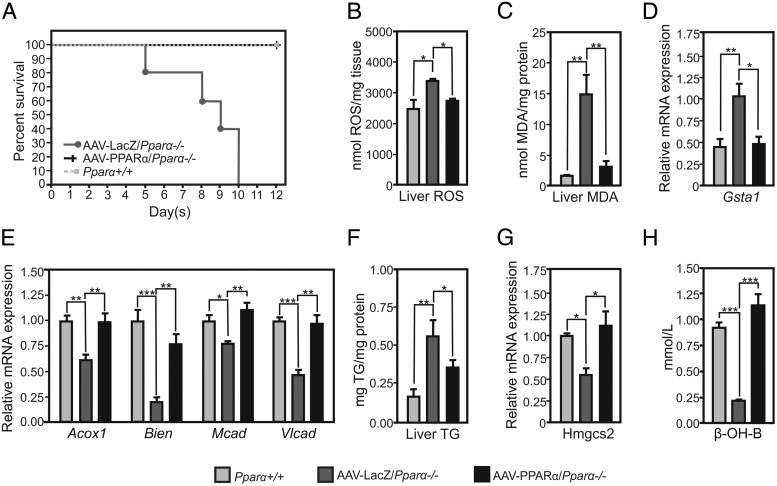

Hepatic PPARα blocks LPO in the liver and protects mice from FO-induced death

To study whether hepatic PPARα could prevent FO-induced ALF, PPARα expression was reconstituted in the liver of Pparα-deficient mice using AAV8 vectors expressing PPARα under control of the hepatocyte-specific Tbg promoter. Liver distribution of the AAV8-delivered transgene was demonstrated histologically 2 weeks after injection of the Pparα-deficient mice with a control AAV8 β-galactosidase (LacZ) (Supplemental Figure 5A). Hepatic PPARα expression was efficiently reconstituted in Pparα-deficient mice, as shown by the presence of PPARα mRNA and protein in the liver (Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). Although Pparα-deficient mice injected with the control LacZ vector died within 10 days after treatment with FO, all Pparα-deficient mice with liver-specific expression of Pparα survived (Figure 3A). Liver-specific PPARα reconstitution decreased hepatic ROS (Figure 3B) and MDA (Figure 3C) as compared with control Pparα-deficient/AAV8-LacZ mice, to levels observed in wild-type mice. In line, hepatic Gsta1 expression levels increased in Pparα-deficient/AAV8-LacZ, but not in Pparα-deficient/AAV8-PPARα mice (Figure 3D). Moreover, hepatic expression of PPARα restored hepatic expression of FA transport and metabolism genes such as Acox1, Bien, Mcad, and Vlcad to wild-type levels (Figure 3E). Although FO treatment of Pparα-deficient mice injected with control AAV8-LacZ increased liver TG, reconstitution of hepatic PPARα decreased TG accumulation in the liver (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. Liver-specific PPARα protects from FO-induced ALF and lipoperoxidation by maintaining FAO and ketogenesis pathways.

A, Kaplan-Meier curve of FO-gavaged wild-type mice (Pparα+/+), AAV-LacZ/Pparα−/−, and AAV-PPARα/Pparα−/− mice (n = 15/group). B, Hepatic ROS levels. C, Hepatic MDA levels. D and E, Hepatic expression of Gsta1 and FAO genes. F, Hepatic TG content. G, Hepatic Hmgcs2 expression. H, Plasma β-OHB levels. Gene expression values are shown relative to WT mice treated with FO (n = 5–6/group). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .005; by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

As previously reported, ALF is associated with hypoketonemia, a reflector of perturbed liver metabolic functions (1). Ketogenesis rates are regulated by PPARα, which controls constitutive expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (Hmgcs2), a rate-limiting enzyme of ketone body synthesis, and plays a role in the metabolic switch for FA use during fasting and upon feeding a high-fat ketogenic diet (22). Although Pparα-deficient mice injected with control AAV8-LacZ displayed decreased expression of hepatic Hmgcs2, liver-specific PPARα expression restored wild-type expression levels of Hmgcs2 (Figure 3G) as well as that of the plasma ketone body β-OHB (Figure 3H). This shows that that hepatic PPARα prevents hypoketonemia in FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice.

Altogether, these results show that liver parenchymal cell PPARα is sufficient and essential to restore β-oxidation and ketogenesis pathways, and thus to protect mice from FO-induced lipotoxicity and death.

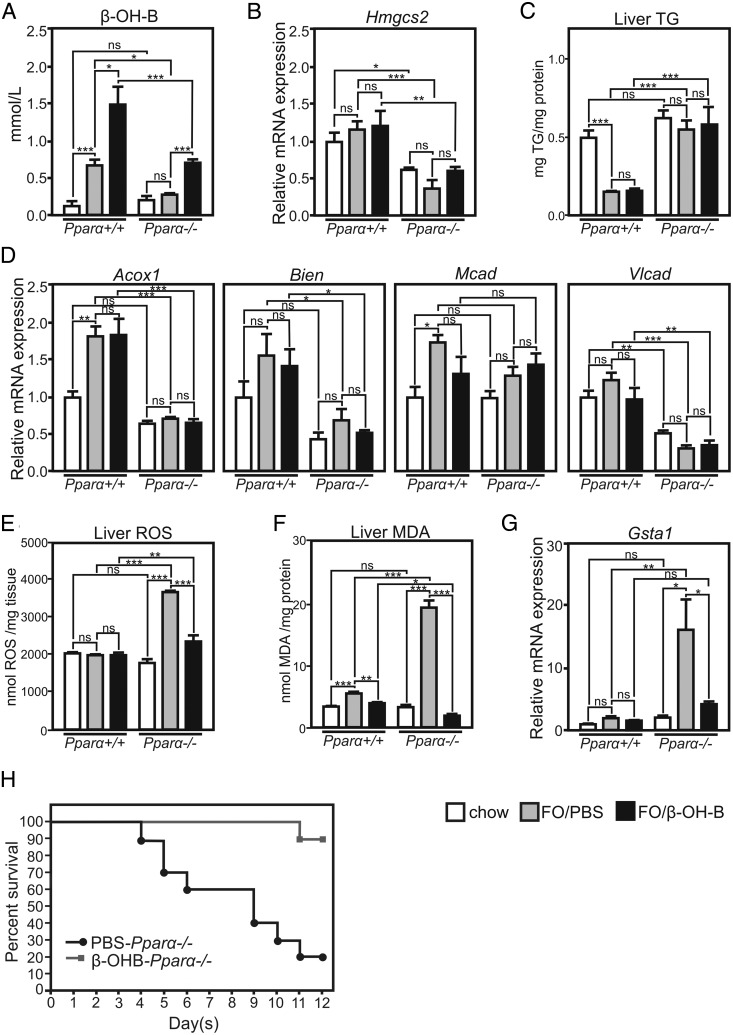

β-OHB treatment blocks LPO in the liver and protects mice from FO-induced lethality

Recent data showed that β-OHB treatment decreases OS and reactive ROS and also reduces the products of LPO (43, 44). To investigate whether decreased ketone body levels play a role in PUFA-induced ALF, FO-gavaged wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice were treated via ip injection with sodium β-OHB (2.5 mg/g·d). Treatment of wild-type mice with FO resulted in an increase of plasma β-OHB levels, whereas β-OHB levels remained unchanged upon FO treatment of Pparα-deficient mice, indicating the requirement of PPARα for endogenous ketone body production (Figure 4A). Indeed, expression of several PPARα target genes, including Hmgcs2, was lower in the knockout mice (Figure 4, B and D). In line, the TG-lowering activity of FO observed in the livers of wild-type mice was abolished in Pparα-deficient mice (Figure 4C). We then restored the β-OHB levels in FO-gavaged Pparα-deficient to those observed in FO-treated wild-type mice by treating mice with β-OHB (Figure 4A). Treatment of wild-type mice with FO only or with both β-OHB and FO did not alter basal levels of liver ROS (Figure 4E), whereas FO significantly elevated their levels in Pparα-deficient mice, an effect prevented by β-OHB cotreatment. Moreover, FO treatment significantly increased liver MDA in both wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice (Figure 4F). However, the increase in hepatic MDA levels was much more pronounced in Pparα-deficient mice. β-OHB treatment lowered MDA levels in both wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice treated with FO, normalizing liver MDA levels to those observed in control diet-fed mice (Figure 4F). A significant increase of hepatic Gsta1 mRNA levels was observed in FO/PBS-treated Pparα-deficient mice only (Figure 4G), an effect abolished by cotreatment of the Pparα-deficient mice with both FO and β-OHB. Because β-OHB may decrease LPO via regulation of genes involved in the response to OS (44), hepatic expression of antioxidative response genes such as forkhead box protein A2 (Foxoa2) and metallothionein 2 (Mt2), known to be up-regulated in the kidney in response to β-OHB infusion (44) was measured in Pparα-deficient mice treated with FO and PBS or β-OHB. Their expression was however not altered in the liver in these conditions (Supplemental Figure 6). These data suggest that the protective, antioxidant activities of β-OHB in the liver are likely due to direct ROS and/or MDA neutralization. To study the impact of β-OHB levels on FO-induced lethality, Pparα-deficient mice were daily injected with either PBS or β-OHB and treated with FO for 12 days. A total of 80% of control Pparα-deficient mice injected with PBS died, whereas 90% of β-OHB-injected animals were protected from death after 12 days of FO treatment (Figure 4H). These results show that β-OHB protects from FO-induced ALF likely by suppressing PUFA peroxidation in the liver.

Figure 4. β-OHB treatment protects from FO-induced ALF by preventing hepatic OS and LPO.

A, Plasma β-OHB levels in wild-type and Pparα-deficient mice fed control chow diet or gavaged with FO and injected with PBS or sodium β-OHB. B and C, Hepatic expression of Hmgcs2 and FAO genes. D, Hepatic TG content. E, Hepatic ROS levels. F, Hepatic MDA levels. G, Hepatic Gsta1 expression. Gene expression values are shown relative to FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice injected with PBS (n = 5–7/group). H, Kaplan-Meier curve of FO-treated Pparα-deficient mice injected with PBS or β-OHB (n = 15/group). *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .005; by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Comparisons between 2 conditions within 1 genotype were performed by unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Severe liver damage involves OS, impaired mitochondrial β-oxidation, and ATP depletion, leading to hepatocyte necrosis and ALF (4). Thus, antioxidant agents, such as N-acetylcysteine, are used in the clinic to prevent drug-induced hepatic injury (10). As recently reported and confirmed in our study, treatment with high-dose FO, which contains n-3 PUFA that are highly susceptible to nonenzymatic peroxidation due to the presence of multiple double-bonds between carbons, increases hepatic ROS and production of toxic LPO-derived aldehydes, such as MDA, that may form complexes with DNA and proteins (29, 45). This in turn induces mitochondrial permeability transition associated with mitochondrial lysis (46). Constitutive levels of FAO enzymes are lower in livers of Pparα-deficient mice (47), which would promote FA peroxidation, accumulation of toxic FA metabolites including MDA and OS upon exposure to PUFA. Accordingly, in our study, we show that treatment with high doses of FO leads to increased LPO in the liver but not in other organs, such as kidney, heart, and muscles, an effect potentiated by PPARα deficiency. Liver-specific increase in MDA levels in Pparα-deficient mice likely results from impaired β-oxidation and clearance of free FA remnants that are preferably transported to the liver upon dietary oil intake. Accumulation of ROS and toxic products of LPO, such as MDA, provoke ALF and death of Pparα-deficient mice upon treatment with FO. Thus, Pparα deficiency predisposes to PUFA-induced ALF as hallmarked by increased ALT, AST, ammonia and lactate plasma levels, and the inability to maintain glucose and ketone body plasma levels, consequently leading to coma and death. By reconstituting PPARα expression in livers of Pparα-deficient mice, we showed that hepatic PPARα is essential in the protection against the detrimental effects of PUFA peroxidation. Similar manifestations were reported in humans suffering from inherited disorders related to deficiency of FAO enzymes such as MCAD, VLCAD, CPT1, and CPT2, which lead to accumulation of long-chain FAs in the liver, all of them being PPARα target genes (8). This raises the hypothesis that decreased hepatic PPARα may predispose individuals to ALF and increase their susceptibility to ALF-inducing factors. Moreover, expression of Pparα is less abundant in human than in mouse liver, which would suggest that humans can be more exposed to OS, such as induced by FO (48). Of note, hepatic Pparα expression is decreased with progressing stages of NASH as well as in critically ill patients with sepsis (Ref. 33 and our unpublished data, respectively). Our data suggest that administrating of n-3 PUFA to these patients may be contraindicated.

The hepatoprotective activities of PPARα are likely related to its metabolic activities via the regulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism in the liver, as suggested by liver-specific reconstitution of PPARα with a parenchymal cell-specific promoter. Besides its ability to regulate FAO genes, PPARα is a master transcriptional regulator of ketogenesis (22). Ketone bodies, such as acetoacetate and β-OHB, are produced by the liver from FA released by adipose tissue upon fasting or ketogenic diets, to be used by peripheral tissues to generate acetyl-CoA for energy production (49). β-OHB is produced, but not metabolized, in the liver, due to very low expression and activity of β-OHB dehydrogenase (50). Recent studies suggest that ketone bodies may offer therapeutic potential in a number of diseases linked to OS by their pleiotropic effects on ROS and aldehyde neutralization in peripheral tissues, such as brain and kidney (44, 51). It has been shown that ROS promote LPO by attacking double-bonds of PUFA, leading to chain breakage and generation of toxic PUFA-derived aldehydes (52). In the MMP+-induced in vitro model of Parkinson's disease, β-OHB decreases ROS production by reducing mitochondrial [NADP+]/[NADPH] and stimulating coenzyme Q oxidation thus increasing metabolic efficiency and energy production (53). Another proposed mechanism of the neuroprotective action of β-OHB stems from its ability to improve mitochondrial respiration and ATP production that results in decreased intracellular ROS levels (51). In patients with multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, treatment with the sodium salt of β-OHB improves cardiac function and brain leukodystrophy (54). These activities of β-OHB prompted us to study whether β-OHB can counteract the PPARα-dependent FO-induced ALF. Interestingly, we found that β-OHB injection in Pparα-deficient mice protects from FO-induced elevation of liver ROS, MDA levels, and hepatic expression of Gsta1a, an enzyme involved in LPO product neutralization (55). Moreover, reconstitution of β-OHB plasma levels protected Pparα-deficient mice from FO-induced ALF and death, suggesting that β-OHB exerts hepatoprotective effects through its ability to neutralize ROS formation and PUFA peroxidation. We tested whether the antioxidative effects of β-OHB could be linked to previously reported activity of β-OHB as an endogenous and specific inhibitor of class I histone deacetylases (44). However, expression of the OS resistance factors Foxo3a and Mt2, regulated in kidney in a β-OHB-dependent manner, remained unchanged in livers of Pparα-deficient mice treated with FO and β-OHB. In accordance, treatment of Pparα-deficient mice with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a synthetic inhibitor of class I histone deacetylases failed to protect Pparα-deficient mice from FO-induced lethality (data not shown), indicating that epigenetic mechanisms are unlikely to be at play in the prevention of FO-induced ALF by β-OHB. Previous reports show that β-OHB decreases mitochondrial permeability transition and oxidative injury in neocortical neurons by decreasing mitochondrial ROS production and LPO (53, 56). The scavenging capacity of acetoacetate and of both physiological and nonphysiological isomers of β-OHB (D- and L-β-OHB, respectively) have been reported for diverse ROS (57). In line, β-OHB treatment of Pparα-deficient mice lowered FO-induced liver ROS to levels observed in untreated mice. This suggests that β-OHB protects from FO-derived PUFA peroxidation and their toxic aldehyde products by scavenging ROS pools in the liver or directly reacting with intracellular MDA. Because patients with ALF have high energy expenditure and require nutritional support to preserve muscle, brain and immunological functions (58), our data suggest that β-OHB could be used in ALF not only to decrease OS but also as an energy substrate for peripheral tissues.

In conclusion, we show that hepatic PPARα is necessary in the protection from FO-derived PUFA peroxidation, ALF and death. The hepatoprotective PPARα activities are associated with its ability to maintain hepatic expression levels of FAO and ketogenesis thus limiting nonenzymatic FA peroxidation. Reconstitution of β-OHB levels either by liver-specific PPARα expression in Pparα-deficient mice or by ip injection protects mice from FO-induced ALF or death, showing that β-OHB can be an option to treat OS-induced liver damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emmanuelle Vallez for technical support in plasma parameter measurements and Corinna Lebhertz for providing AAV vectors. B.S. is a member of the Institut Universitaire de France.

Author contributions: M.P., E.B., P.L., and B.S. conceived and designed the study; M.P., E.B., and F.L. acquired data; M.P., E.B., F.L., P.L., and B.S. analyzed and interpreted data; M.P. drafted of the manuscript; M.P., E.B., F.L., P.L., and B.S. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; P.L. and B.S. obtained funding; and P.L. and B.S. supervised the study.

This work was supported in part by a fellowship from the French Ministry for Education and Research (M.P.). This work was also supported by the European Genomic Institute for Diabetes Grant ANR-10-LABX-46 and by the European Commission. B.S. is part of a research community on nuclear receptors supported by Research Foundation Flanders-Vlaanderen (Research Foundation Flanders-Wetenschappelijke Onderzoeksgemeenschap).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by a fellowship from the French Ministry for Education and Research (M.P.). This work was also supported by the European Genomic Institute for Diabetes Grant ANR-10-LABX-46 and by the European Commission. B.S. is part of a research community on nuclear receptors supported by Research Foundation Flanders-Vlaanderen (Research Foundation Flanders-Wetenschappelijke Onderzoeksgemeenschap).

Footnotes

- AAV

- adeno-associated virus

- AAV8

- adeno-associated serotype 8 virus

- ALF

- acute liver failure

- ALT

- alanine aminotransferase

- APAP

- acetaminophen

- AST

- aspartate aminotransferase

- Bien

- enoyl-CoA hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- CoA

- coenzyme A

- CPT

- carnitine palmitoyltransferase

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic

- EPA

- eicosapentaenoic acid

- Faldh

- fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase

- FAO

- FA oxidation

- FO

- fish oil

- GST

- Glutathione S-transferase

- Gsta1

- glutathione S-transferase α1

- Hmgcs2

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2

- LCAD

- long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- LPO

- lipid peroxidation

- MDA

- malondialdehyde

- NASH

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- β-OHB

- β-hydroxybutyrate

- OS

- oxidative stress

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated FA

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SO

- sunflower oil

- Tbg

- thyroxine-binding globulin

- TG

- triglyceride

- VLCAD

- very-LCAD.

References

- 1. Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gotthardt D, Riediger C, Weiss KH, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure: etiology and indications for liver transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(suppl 8):viii5–viii8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGill MR, Staggs VS, Sharpe MR, Lee WM, Jaeschke H. Serum mitochondrial biomarkers and damage-associated molecular patterns are higher in acetaminophen overdose patients with poor outcome. Hepatology. 2014;60:1336–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu H, Han T, Tian J, et al. Monitoring oxidative stress in acute-on-chronic liver failure by advanced oxidation protein products. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bantel H, Schulze-Osthoff K. Mechanisms of cell death in acute liver failure. Front Physiol. 2012;3:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Williams CD, Taha M, Curry SC, Jaeschke H. The mechanism underlying acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1574–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baruteau J, Sachs P, Broué P, et al. Clinical and biological features at diagnosis in mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation defects: a French pediatric study of 187 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alonso EM. Acute liver failure in children: the role of defects in fatty acid oxidation. Hepatology. 2005;41:696–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Natarajan SK, Thangaraj KR, Eapen CE, et al. Liver injury in acute fatty liver of pregnancy: possible link to placental mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Hepatology. 2010;51:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heard KJ. Acetylcysteine for acetaminophen poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferret PJ, Hammoud R, Tulliez M, et al. Detoxification of reactive oxygen species by a nonpeptidyl mimic of superoxide dismutase cures acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in the mouse. Hepatology. 2001;33:1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gulick T, Cresci S, Caira T, Moore DD, Kelly DP. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor regulates mitochondrial fatty acid oxidative enzyme gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11012–11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP. A critical role for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in the cellular fasting response: the PPARα-null mouse as a model of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7473–7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu Y, Boekschoten MV, Wopereis S, Müller M, Kersten S. Comparative transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of fenofibrate and fish oil treatments in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:1307–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin PG, Guillou H, Lasserre F, et al. Novel aspects of PPARα-mediated regulation of lipid and xenobiotic metabolism revealed through a nutrigenomic study. Hepatology. 2007;45:767–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ip E, Farrell G, Hall P, Robertson G, Leclercq I. Administration of the potent PPARα agonist, Wy-14,643, reverses nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;39:1286–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patterson AD, Shah YM, Matsubara T, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α induction of uncoupling protein 2 protects against acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity. Hepatology. 2012;56:281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Tanaka N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology. 2004;40:972–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toyama T, Nakamura H, Harano Y, et al. PPARα ligands activate antioxidant enzymes and suppress hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashibe B, Motojima K. Fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase is up-regulated by polyunsaturated fatty acid via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and suppresses polyunsaturated fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J. 2009;276:6956–6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pawlak M, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:720–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1489–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patsouris D, Reddy JK, Müller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the effects of high-fat diet on hepatic gene expression. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1508–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikeda I, Cha JY, Yanagita T, et al. Effects of dietary α-linolenic, eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on hepatic lipogenesis and β-oxidation in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dallongeville J, Baugé E, Tailleux A, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α is not rate-limiting for the lipoprotein-lowering action of fish oil. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4634–4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim HJ, Takahashi M, Ezaki O. Fish oil feeding decreases mature sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) by down-regulation of SREBP-1c mRNA in mouse liver. A possible mechanism for down-regulation of lipogenic enzyme mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25892–25898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miret S, Sáiz MP, Mitjavila MT. Effects of fish oil- and olive oil-rich diets on iron metabolism and oxidative stress in the rat. Br J Nutr. 2003;89:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takahashi M, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Nakatani T, et al. Fish oil feeding alters liver gene expressions to defend against PPARα activation and ROS production. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G338–G348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feillet-Coudray C, Aoun M, Fouret G, et al. Effects of long-term administration of saturated and n-3 fatty acid-rich diets on lipid utilisation and oxidative stress in rat liver and muscle tissues. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1789–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Pérez-Espinosa A, Vázquez CM, Santa-María C. Effects of dietary fats (fish, olive and high-oleic-acid sunflower oils) on lipid composition and antioxidant enzymes in rat liver. Br J Nutr. 1999;82:233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Larter CZ, Yeh MM, Cheng J, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α by dietary fish oil attenuates steatosis, but does not prevent experimental steatohepatitis because of hepatic lipoperoxide accumulation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Argo CK, Patrie JT, Lackner C, et al. Effects of n-3 fish oil on metabolic and histological parameters in NASH: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2015;62:190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Francque S, Verrijken A, Caron S, et al. PPARα gene expression correlates with severity and histological treatment response in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee SS, Pineau T, Drago J, et al. Targeted disruption of the α isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3012–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jelinek D, Castillo JJ, Arora SL, Richardson LM, Garver WS. A high-fat diet supplemented with fish oil improves metabolic features associated with type 2 diabetes. Nutrition. 2013;29:1159–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pawlak M, Bauge E, Bourguet W, et al. The transrepressive activity of Pparα is necessary and sufficient to prevent liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2014;60:1593–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hashimoto T, Fujita T, Usuda N, et al. Peroxisomal and mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation in mice nullizygous for both peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and peroxisomal fatty acyl-CoA oxidase. Genotype correlation with fatty liver phenotype. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19228–19236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pizzimenti S, Ciamporcero E, Daga M, et al. Interaction of aldehydes derived from lipid peroxidation and membrane proteins. Front Physiol. 2013;4:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prabhu KS, Reddy PV, Jones EC, Liken AD, Reddy CC. Characterization of a class α glutathione-S-transferase with glutathione peroxidase activity in human liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;424:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ong JP, Aggarwal A, Krieger D, et al. Correlation between ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med. 2003;114:188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bernal W. Lactate is important in determining prognosis in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2010;53:209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Silverman J. Clinical biochemistry parameters in C57BL/6J mice after blood collection from the submandibular vein and retroorbital plexus. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2010;49:400; author reply 400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cheng B, Yang X, Chen C, Cheng D, Xu X, Zhang X. D-β-hydroxybutyrate prevents MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339:211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burns CP, Wagner BA. Heightened susceptibility of fish oil polyunsaturate-enriched neoplastic cells to ethane generation during lipid peroxidation. J Lipid Res. 1991;32:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kristal BS, Park BK, Yu BP. 4-Hydroxyhexenal is a potent inducer of the mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6033–6038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hashimoto T, Cook WS, Qi C, Yeldandi AV, Reddy JK, Rao MS. Defect in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-inducible fatty acid oxidation determines the severity of hepatic steatosis in response to fasting. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28918–28928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Palmer CN, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Raucy JL, Johnson EF. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α expression in human liver. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Laplante M, Oh S, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 controls fasting-induced ketogenesis and its modulation by ageing. Nature. 2010;468:1100–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nielsen NC, Fleischer S. β-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase: lack in ruminant liver mitochondria. Science. 1969;166:1017–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tieu K, Perier C, Caspersen C, et al. D-β-hydroxybutyrate rescues mitochondrial respiration and mitigates features of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Long EK, Picklo MJ Sr. Trans-4-hydroxy-2-hexenal, a product of n-3 fatty acid peroxidation: make some room HNE. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kashiwaya Y, Takeshima T, Mori N, Nakashima K, Clarke K, Veech RL. D-β-hydroxybutyrate protects neurons in models of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5440–5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Hove JL, Grünewald S, Jaeken J, et al. D,L-3-hydroxybutyrate treatment of multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MADD). Lancet. 2003;361:1433–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Awasthi YC, Yang Y, Tiwari NK, et al. Regulation of 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated signaling by glutathione S-transferases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:607–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mejía -Toiber J, Montiel T, Massieu L. D-β-hydroxybutyrate prevents glutamate-mediated lipoperoxidation and neuronal damage elicited during glycolysis inhibition in vivo. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:1399–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haces ML, Hernández-Fonseca K, Medina-Campos ON, Montiel T, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Massieu L. Antioxidant capacity contributes to protection of ketone bodies against oxidative damage induced during hypoglycemic conditions. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walsh TS, Wigmore SJ, Hopton P, Richardson R, Lee A. Energy expenditure in acetaminophen-induced fulminant hepatic failure. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]