Abstract

Probing the multiplicity of hormone signaling via G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) has demonstrated the complex signal pathways that underlie the multiple functions these receptors play in vivo. This is highly pertinent for the GPCRs key in reproduction and pregnancy that are exposed to cyclical and dynamic changes in their extracellular milieu. How such functional pleiotropy in GPCR signaling is translated to specific downstream cellular responses, however, is largely unknown. Emerging data strongly support mechanisms for a central role of receptor location in signal regulation via membrane trafficking. In this review, we discuss current progress in our understanding of the role membrane trafficking plays in location control of GPCR signaling, from organized plasma membrane signaling microdomains, potentially provided by both distinct endocytic and exocytic pathways, to more recent evidence for spatial control within the endomembrane system. Application of these emerging mechanisms in their relevance to GPCR activity in physiological and pathophysiological conditions will also be discussed, and in improving therapeutic strategies that exploits these mechanisms in order to program highly regulated and distinct signaling profiles.

Within any cellular signaling system it is becoming apparent that signal location is a critical mechanism for cells to translate complex signaling networks at a spatial and temporal level, into specific downstream responses. The membrane trafficking of receptors and the signaling molecules they activate, can direct the location of intracellular signals, and has such been viewed as an integrated cross-regulatory cellular system (1). Thus, membrane trafficking can regulate many fundamental cellular programs and an increasing number of clinical conditions have been reported to result from defects in membrane trafficking pathways or cargo sorting (1, 2). The role of location in signal regulation via membrane trafficking is highly pertinent for the signaling activated by the superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). A well-established contribution that trafficking plays in GPCR signaling is the ability to regulate heterotrimeric G protein signal patterns (3). A simple but dramatic example is the divergent sorting of GPCRs after ligand-induced endocytosis to either recycling or degradative/lysosomal pathways (see Figure 1), a process that essentially produces opposite effects on receptor signaling via its cognate G proteins (3). Furthermore, the potential to reprogram signaling by altering trafficking or location of receptors may be a key adaptive mechanism for GPCRs that are exposed to cyclical and dynamic hormonal environments, such as those receptors central to regulating reproduction and pregnancy. In this review, we will highlight the recent advances in our understanding that membrane trafficking plays in location control of GPCR signaling, focusing where possible on reproductive-relevant GPCRs, and the potential therapeutic application and exploitation of these findings.

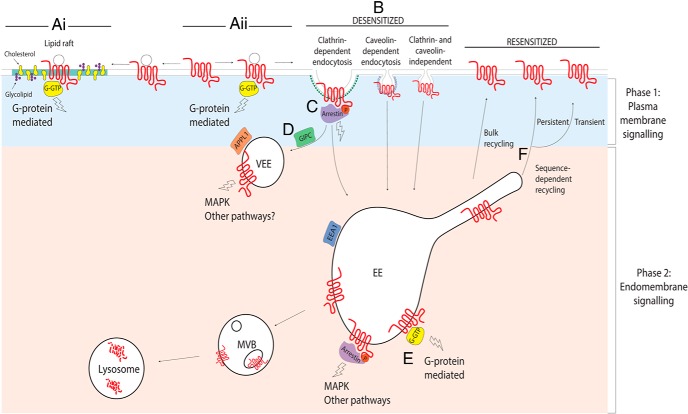

Figure 1. A cellular model for spatial control of GPCR signaling across the plasma membrane and endomembrane system.

After agonist binding, GPCRs can be directed into distinct plasma membrane microdomains such as lipid rafts (Ai) or, after activation and subsequent desensitization (Aii), several GPCRs are known to undergo endocytosis via clathrin dependent or independent mechanisms (B). CCPs allow accumulation of GPCR/arrestin complexes that can activate arrestin-mediated mitogenic signaling (C). After internalization, GPCRs will accumulate in endosomal compartments where they can continue or reactivate heterotrimeric G protein signaling from the endosomal membrane, in addition to scaffolding arrestin to activate G protein-independent signal responses (D and E). Some GPCRs are differentially sorted to a distinct endosomal population termed pre-EEs or VEEs (D), via recruitment and binding of the PDZ protein GIPC at the CCP. The VEE sorts receptors to the regulated, sequence-directed plasma membrane recycling pathway and targeting of GPCRs to this compartment generates a sustained MAPK signaling response, although it is unknown whether other pathways, including G protein signaling, are activated in this compartment. Other GPCRs are directly routed to the EE, where they are differentially sorted between recycling and degradative/lysosomal pathways, leading to heterotrimeric G protein plasma membrane signal resensitization or signal termination, respectively. Reinsertion in to the plasma membrane of GPCRs targeted to the recycling pathway (F) exhibits distinct spatiotemporal patterns of insertion, either transient or persistent (see text), although its role in spatial control of signaling in addition to resensitization is unknown. G-GTP, GTP-bound form of the G protein; MVB, multivesicular body.

Clathrin-Coated Pits (CCPs). More Than Just a Mode of Endocytosis?

The removal of GPCRs from the cell surface, via the process of endocytosis, is well established to regulate receptor signaling by contributing to heterotrimeric G protein signal desensitization. Several pathways have been described to regulate receptor-mediated endocytosis. However, clathrin-mediated endocytosis via CCPs is the most extensively characterized. CCPs are formed by the recruitment and ordering of clathrin coat proteins with cargo, accessory proteins and adaptors (Figure 1B; reviewed in Refs. 4, 5). A new vesicle is then formed after the scission of the CCP from the membrane by the dynamin family of GTPases (6). The widely accepted model for GPCR recruitment to CCPs is that a ligand-activated receptor is first phosphorylated (by a member of the family of the GPCR kinases [GRKs]), which increases the affinity of the cytoplasmic adaptor proteins arrestin 2 and/or 3 to the receptor. Arrestins have the ability to bind clathrin heavy chain, β(2)adaptin subunit of the clathrin adaptor protein 2 and GPCRs, thus facilitating GPCR recruitment and clustering into CCPs for their subsequent internalization (reviewed in Ref. 7). In addition to uncoupling heterotrimeric G protein signaling from the plasma membrane, arrestins also directly activate GPCR signaling independent of their cognate G proteins, by acting as scaffolds for a variety of signaling proteins (Figure 1C). Distinct GPCRs can vary in how they engage in receptor-mediated endocytosis, including preferential arrestin recruitment, phosphorylation via distinct kinases, ligand-independent internalization, and even arrestin- and/or clathrin-independent internalization. This has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (8–11). Instead, we will focus on how these pathways, machinery and distinct clathrin-containing plasma membrane domains may enable tight control of cell surface organization as a mechanism to exquisitely regulate cell signaling.

The diverse range of cargo and machinery reported to assemble to CCPs has raised the question of whether there is heterogeneity in localization across CCPs for different receptors, and in turn whether this impacts subsequent sorting and signal activity of a receptor. That distinct receptors may be organized within distinct subsets of CCPs was first reported for the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) (12). A role for such specialized spatial organization of CCPs was then demonstrated to dictate its subsequent sorting to recycling or lysosomal pathways (13), as also shown for the purinergic receptors, P2Y(1) and P2Y(12), that identified 2 distinct CCP populations (14, 15) also with functional implications in differential postendocytic sorting. Mechanistically, the targeting of receptors to these distinct CCPs was dependent on arrestin and phosphorylation, with P2Y(12) and β2ARs recruited in an arrestin and GRK-dependent manner and P2Y(1) in an arrestin-independent yet protein kinase C-dependent manner. An additional GPCR well known to internalize via an arrestin-independent manner is the mammalian gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) (16). Although reported to localize to clathrin and caveolae/lipid rafts depending on the cell type (see below), this receptor rapidly recycles after ligand-induced internalization (17), unlike the arrestin-independent P2Y(1), so it is possible there may be further subspecializations of CCPs that is dictated by associating adaptor molecules. The impact of such subspecialization on receptor activity, and consequently its downstream physiological function, may be to function as bona fide signaling microdomains, eg, via arrestin-dependent signal complexes (Figure 1C). The potential role of CCPs to act as signaling microdomains is highlighted by the ability of GPCRs to regulate their own CCP residency time. For the β2AR, this is achieved by interaction with additional protein scaffold proteins, namely postsynaptic density 95/disc large/zonula occludens-1 (PDZ) proteins, that tether GPCRs to cortical actin, and extend the occupancy time of a receptor in a CCP by delaying the recruitment of dynamin (15). However, other receptors such as the μ-opioid receptor delay the scission activity rather than recruitment of dynamin, and in a PDZ-independent manner (18). Functionally delayed residency time of a GPCR in CCPs provides a mechanism to regulate mitogenic signals on a temporal scale via formation of arrestin signaling scaffolds, as suggested by a recent study measuring residency times with distinct agonists of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) receptor (19). The CB1 cannabinoid receptor, as part of the endocanabinoid system, modulates synaptic function, including negative regulation of gamma-Aminobutyric acid-ergic input to GnRH neurons, suppressing GnRH output and fertility (20), and thus, such spatiotemporal regulation of CB1 signaling may be key in its role in modulating release of gamma-Aminobutyric acid from the presynaptic membrane under physiological or pathophysiological conditions, eg, the ability of cannabis to inhibit pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion. Additional downstream cellular consequences for tight spatial control of GPCR signaling, such as that generated from CCPs, has been recently demonstrated between the protease-activated receptor 2 and neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor whose arrestin-dependent ERK signaling mediates either cell migration (protease-activated receptor 2) or proliferation (NK1 receptor) via differential ERK localization (21). Although arrestin-recruitment or postendocytic trafficking fate of a GPCR could dictate the localization of receptors in to distinct CCPs, clathrin-associated adaptors such as arrestin and adaptor protein 2 represent core CCP machinery utilized by many kinds of receptors, but it is uncertain whether there are additional machinery that could direct receptors into distinct pits. It has been postulated, however, that organization of receptors across CCPs may be initiated via the differential phosphorylation of GPCR intracellular domains (22), although it remains to be determined whether this dictates any adaptor protein specificity in addition to the arrestins.

Lattices and plaques-novel clathrin-containing structures to regulate GPCR signaling in reproduction?

Additional plasma membrane clathrin-coated structures, clathrin plaques and clathrin flat lattices, have been recently reported to be potential sites of GPCR organization at the plasma membrane (23, 24). Although observed by cell biologists for many years, these recent studies have proposed that they are perhaps unprecedented signal microdomains for GPCRs. These large and stable clathrin-coated structures, with distinct morphologies to CCPs, are present in different cell types, and where GPCRs such as the β2AR, μ-opioid receptor, and the chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) can localize. For CCR5, ligand activation specifically reorganized the receptor to flat clathrin lattices. The stable nature of these structures compared with CCPs has led to the suggestion it represents a mechanism to functionally compartmentalize the activated form of the receptor in the plasma membrane and thereby act as a platform for receptor signaling and/or desensitization (24). CCR5 is a key receptor for the immune system, and although expressed in leukocytes, CCR5 and its ligand are found in other cell types in the reproductive tract, where its expression in human endometrium is thought to regulate blastocyst implantation (25). Besides the presence of the ligand Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted in follicular fluid and CCR5 on human sperm, its role in chemotaxis of human sperm (26) is of interest in patients with endometriosis and genital tract inflammatory diseases, where high levels of Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted induces a premature acrosome reaction and may underlie the subfertility observed in these patient groups (27). These physiological/pathophysiological roles of CCR5 may reflect the impact of a sustained CCR5 signal profile by localization to such plasma membrane coated structures. Interestingly, cell adhesion is thought to occur at membrane sites containing these clathrin-coated structures (23, 24), and an example where clathrin-coated structures are known to exist at sites of intercellular interactions are tubulobulbar complexes in the testes. Tubulobulbar complexes are elongated tubular extensions that project either from spermatids or, from Sertoli cells into corresponding invaginations of adjacent Sertoli cells at sites of cell/cell junctions (28). Characteristically, each membrane complex is capped by a clathrin-coated structure that is highly stable and does not undergo scission; features of the more stable clathrin lattices and plaques rather than the classic CCPs they are proposed to be (28). No GPCRs have been identified to date to be present in these clathrin-coated structures. However, given the expression of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor (FSHR) in Sertoli cells and the numerous GPCRs that have been reported to be expressed in sperm (29–31), they could represent an important spatial mechanism in intercellular communication for GPCRs and spermatocyte translocation and release.

Arrestin-dependent signaling and its role in reproduction

The ability of arrestin-mediated trafficking to activate cell signaling, in addition to G protein signal desensitization, has been the topic of extensive study for many years and is of current high interest as a valid pathway for pharmaceutical targeting with clinical benefits (32, 33). Arrestins can link a number of effectors to agonist-bound GPCRs, for instance Src family tyrosine kinases, components of the MAPK cascade (ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinases) and ubiquitin ligases (Mouse double minute 2 homolog) (34), giving rise to distinctive temporal and spatially regulated signaling modes induced by GPCRs. These distinct signal modalities provide a mechanism for diversifying signaling via a single class of proteins, and for receptors exposed to dynamic hormonal environments, such as those in reproduction and pregnancy, a way to potentially reprogram GPCR signal pathways as a physiological adaptive mechanism.

The gonadotropin hormone receptors, FSHR and LH receptor (LHR), recruit arrestin for desensitization of gonadotropin hormone-induced signaling but also activation of non-G protein-mediated pathways in the ovary and testis. For LHR, the midcycle LH surge results in desensitization of Gαs-adenylate cyclase-cAMP signaling in ovarian follicles, a process mediated by arrestin 2 and requiring the ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) nucleotide-binding site opener. ARF nucleotide-binding site opener releases arrestin 2 from its membrane-docking site and a guanine nucleotide exchange factor of the small G proteins ARF6, promotes binding of arrestin to the LHR (35, 36). Desensitization of Gαs signaling during the LH surge may “bias” the receptor towards other G protein pathways, namely Gαq/11, which is involved in ovulation (37), and/or MAPK pathways, although the involvement of arrestin in these pathways in the ovary remains to be determined. However, arrestin can mediate mitogenic signaling from LHR in testicular Leydig cells, where LHR activates MAPK signaling via an arrestin3/Fyn complex that releases epidermal growth factor-like factors to activate ERK (38). Furthermore, this LH and epidermal growth factor receptor cross talk is important in driving testosterone production in vivo (39). For FSHR, although it can recruit arrestins and GRKs to desensitize its G protein signaling, it can also induce MAPK signaling via the arrestins. The ability of FSHR to activate MAPK signaling independent of the cAMP pathway likely underlies the subfertility phenotype in an inactivating FSHR mutation (A189V) identified in male patients that exhibits impaired cAMP signaling, but maintains arrestin-dependent ERK activation (40).

GPCR signaling is also tightly controlled during pregnancy and undergoes dramatic adaptive changes during labor where oxytocin (OT) receptor (OTR) is central to these processes. Arrestins 2 and 3 in the mouse myometrium negatively regulate OTR-induced contractions, where arrestin2/3 null mice exhibit a lack of OT-induced desensitization (41). Interestingly, in human myocytes, arrestins 2 and 3 play contrasting roles in signal desensitization and activation of MAPK signaling. Arrestin 2 is involved in G protein desensitization, whereas arrestin 3 mediates ERK signaling responses (42). Such arrestin-specific regulation may be a mechanism to modulate distinct prolabor functions of OTR, namely contractions and inflammation (43, 44). More recently a central role for arrestins in regulating hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function at the level of the kisspeptin receptor has been demonstrated whereby either arrestin 2 or arrestin 3 knockout mouse models exhibited a diminished kisspeptin-dependent LH secretion (45). This suggests that activation of arrestin-mediated ERK signaling by the kisspeptin receptor is an important pathway in reproduction and an explanation why known inactivating kisspeptin receptor mutations (in terms of Gαq/11 signaling) results in only partial gonadotropic deficiency (45).

Lipid Rafts and Caveolae as GPCR Signaling Microdomains

Lipid rafts and caveolae are defined as planar microdomains of the plasma membrane enriched in specific lipids and proteins such as cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins or for caveolae, caveolin (Cav) proteins (Figure 1Ai). Lipid rafts are known to be involved with various cell functions such as cholesterol homeostasis, protein and lipid sorting and vesicular transport (46, 47). Importantly, they are known to regulate cell signaling at the plasma membrane by organizing receptors with its signaling machinery; heterotrimeric G proteins, effector enzymes such as adenylate cyclase, and regulators of G protein signaling (eg, regulator of G-protein signaling 16) (48). Thus, disruption of lipid raft formation can abolish signaling from certain GPCRs, including the NK1 receptor (49) and the serotonin 1A receptor (50).

Localization of GPCRs to lipid rafts can occur in a constitutive or ligand-dependent manner. Raft-localized GPCRs exhibit a small amount of constitutive partitioning to lipid rafts, which is then increased upon ligand stimulation. However, the murine GnRHR has been shown to exclusively reside in cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains in certain cell types (51, 52). Mammalian GnRHRs are unique to the GPCR superfamily by their lack of an intracellular C-terminal tail. However, this has been shown to not be the only contributing factor involved in lipid-raft localization as addition of the chicken GnRHR C-terminal tail had no effect on raft localization (53, 54). In contrast, the C-terminal tail of the nonlipid raft associated LHR could reorganize the GnRHR into nonraft regions of the plasma membrane, (53, 55), even though LHR has been observed to form ordered plasma membrane microdomains after hormone stimulation (56, 57). Interestingly, pituitary gonadotropes do not contain caveloae (54), yet the lipid raft protein flottilin-1 is highly expressed and associates with GnRHRs (51), suggesting that the nature of the lipid rafts in gonadotropes are distinct. The role of these microdomains on GnRH signaling is proposed as a mechanism to compartmentalize calcium signaling via L-type calcium channels in gonadotropes as a required element of GnRH-induced ERK signaling. More recently, total-internal reflection microscopy (TIRF-M) studies in the gonadotrope cell line αT3–1 provided direct visual evidence for organized plasma membrane calcium influx events termed “calcium sparklets” (58). Ultimately, such spatial control of calcium and ERK signaling by GnRHR may be required to regulate key functions such as LHβ synthesis and secretion (59). Furthermore, they may also represent a platform for receptor cross talk. Indeed both the glucocorticoid receptor and insulin receptors have been reported to localize to GnRHR-containing lipid raft/microdomains (53, 54) For the glucocorticoid receptor, localization to lipids rafts with GnRHR and activation of both receptors was required for the synergistic inhibition of cell proliferation via PKC activation and serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 transcription (60). Interestingly, insulin and GnRHR containing microdomains exhibit asymmetric functionality, whereby insulin enhances GnRH-induced ERK signaling, yet GnRH inhibits activation of insulin-mediated phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway (54). This study highlights the important contributions of metabolic pathways in reproduction, and potentially in conditions such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), where hyperinsulinaemia could be coupled to the high circulating LH levels found in subsets of women with PCOS (61). However, most studies are carried out under sustained treatments of GnRH, yet GnRH stimulation is both pulsatile and dynamic, and this has been recently shown to impact on its MAPK signaling (62). Therefore, an important next step is to understand how these microdomains contribute to its signaling responses under such dynamic conditions in vivo.

Despite the caveats involved in the biochemical study of lipid rafts (for review please see Ref. 63), the identification that caveolae contain Cav proteins Cav1, Cav2, and/or Cav3 (the latter being muscle-specific) (64) provided a molecular “tag” to study these microdomains. Certain GPCRs have reported to internalize via caveolae, although the molecular detail in how this process occurs is not well understood (65). However, like lipid rafts, they can also act as GPCR signalosomes, both as a means to spatially desensitize and also locally amplify signal responses. Many GPCRs, G protein subunits, and effector enzyme systems have been shown to be sequestered by caveolae (66, 67). One example of a signaling complex mediated by Cav1 is that of Gαq and phospholipase C, which results in elevated levels of inositol triphosphate (68). Such enhancement of Gαq signaling may underlie the caveolae-dependent antiproliferative action of OTR in prostatic stromal cells with implications in the dysregulation of this pathway in aging and prostate cancer (69).

Plasma Membrane Organization of Recycled Receptors

After GPCR endocytosis, many receptors are targeted to a recycling pathway back to the plasma membrane, resulting in resensitization or recovery of hormone signaling (Figure 1F). GPCRs are sorted to the recycling pathway via a sequence-directed mechanism requiring specific cis-acting sorting sequences in their C-terminal tails (3, 70, 71). This is in contrast to receptors that recycle in the absence of sorting sequences and occur in a “default” manner via the bulk membrane flow. For some receptors such as the β2AR, recycling sequences are type 1 PDZ ligands (72, 73) and β2AR associates with the PDZ protein sorting nexin-27 for its postendocytic trafficking (74). However, the high diversity in recycling sequences across GPCRs suggests that they bind specific cytoplasmic proteins (3). We refer the reader to reviews describing the endosomal mechanisms mediating postendocytic sorting to these pathways via highly diverse GPCR recycling sequences (3, 70). In terms of plasma membrane organization of GPCR signaling, recent reports studying the events downstream of endosomal sorting of GPCRs back to the plasma membrane may indicate that such pathways could direct receptors to defined plasma membrane domains. Such studies have employed N-terminal labeling of GPCRs with superecliptic pHluorin (which is fluorescent at neutral pH and nonfluorescent at acidic pH [pH < 6.0] that occurs within the acidic lumen of the endosome), coupled with TIRF-M imaging and has enabled direct visualization of individual receptor insertion events into the plasma membrane at high temporal resolution (71, 75, 76). The β2AR and μ-opioid receptor both undergo sequence-directed recycling and these studies imaging individual recycling events revealed that GPCR recycling 1) occurs at a much faster rate after ligand stimulation than previously detected by other approaches and 2) exhibited distinct spatiotemporal patterns of insertion. Both transient and “persistent” insertion events of receptor containing vesicles have been described, the former remaining for less than 1 second whereas the persistent for more than 10 seconds before the receptor laterally diffuses in to the membrane. The type of events exhibited seems to be cell type dependent, because the persistent events were primarily a feature of neurons and not in heterologous cell lines such as HEK 293 cells or astrocytes and fibroblasts (75, 77). It remains to be determined whether other cell types exhibit these kind of persistent fission events and what functional role they may play, although a role for these events as specialized signaling complexes has been proposed (75). Interestingly, both recycling events seem to be regulated by distinct mechanisms, with the transient events negatively regulated by protein kinase A (PKA) and agonist, whereas the persistent is positively regulated by agonist yet PKA independent. Given the role of GPCR-induced cAMP-PKA signaling in these recycling events, one possible signaling complex involved in regulating and/or perhaps integrating a functional response from these newly recycled receptors are the A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs).

The AKAPs are a large family of scaffolding proteins that facilitate GPCR signaling by binding to the regulatory subunits of the PKA via their C-terminal motif (reviewed in Refs. 78, 79). In addition to the ability of AKAP to interact with PKA, AKAPs are also known to mediate signal transduction by scaffolding signaling machinery such as adenylate cyclase and serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases, as well as signal termination molecules such as phosphatases and phosphodiesterases. Therefore, AKAP can form specialized signaling microdomains or stations, which can allow spatiotemporal regulation of signaling. AKAPs such as AKAP12 (also termed Gravin or AKAP250) have been shown to preferentially associate with the β2AR at the plasma membrane and are involved in regulating the recycling of this GPCR (80, 81). Additional AKAPs implicated in regulation of β2AR receptor activity are AKAP5 (also termed AKAP79/150), which interestingly is specifically required for ERK activation without affecting cAMP signaling or recycling (82). Whether such scaffolding proteins could reflect a potential functional role of persistent and/or transient recycling events remains to be determined. However, AKAP5 and 7α have been implicated in maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest, and because both constitutive endocytosis and recycling are required of the GPCRs responsible for maintaining this cAMP signaling (GPR3/6/12), this suggests that spatial scaffolding of cAMP signaling of these recycling GPCRs is important in oocyte maturation (83–85).

Endosomal GPCR Signaling

As described above, the paradigmatic model of GPCR signaling depicted plasma membrane localized receptors activating a distinct heterotrimeric G protein signaling pathway that in turn converges on to common downstream pathways, such as MAPK signaling. Our current understanding of the high complexity in these pathways now include the well-described ability of key GPCR adaptor proteins, ie, arrestins, in generating distinct signaling patterns at specific membrane locations. However, more recently there has been an emerging body of data demonstrating that G protein signaling from receptors can occur beyond the plasma membrane (ie, at the level of endosomes) and that signaling could be regulated across endosomal populations, thus GPCR signaling can therefore be broadly categorized in to 2 phases: plasma membrane signaling (phase 1) and endomembrane signaling (phase 2) (see Figure 1). Pivotal studies demonstrating that GPCRs continue to activate, or exhibit persistent, heterotrimeric G protein signaling after internalization was shown with 2 Gαs-coupled receptors, the TSH receptor and the PTH receptor (PTHR). These studies employed cAMP biosensors that demonstrated persistent cAMP signaling required internalization, the machinery to generate such persistent cAMP signals, Gαs, and adenylate cyclases were localized in early endosomes (EEs) and that this persistent endosomal signaling is potentially physiologically relevant (as demonstrated for TSH receptor in 3-dimensional cultures of thyroid follicles) (86, 87). For PTHR, endosomal cAMP generation was shown to be enhanced by arrestin and attenuated by the retromer complex involved in receptor recycling (88) and that endosomal acidification plays a key role in this deactivating switch (89). The PTHR has critical roles in regulating Ca2+ homeostasis by its actions on bone and kidney, and the sustained signaling induced by distinct PTH ligands in turn impacts on trabecular bone volume but induces greater increases in cortical bone turnover. Such features of PTHR signaling may be exploited therapeutically such as in certain forms of hypoparathyroidism that respond to PTH. However, the authors propose that the PTH analogs that induce sustained signaling lead to enhanced cortical bone turnover, thus conditions such as osteoporosis may not benefit from PTH ligands with sustained signaling properties (90).

Direct evidence that a GPCR can activate heterotrimeric G proteins from endosomes came from a seminal study that developed a nanobody biosensor to detect either the active, nucleotide-free form of Gαs or the ligand-activated conformation of the β2AR (91). These nanobodies were originally generated as tools to aid crystallization of this GPCR in distinct active conformations (92), but the application as a biosensor for imaging in live cells revealed that β2AR and Gαs were reactivated upon reaching the EE membrane (91). The functional role of this endosomal Gαs-cAMP signaling has been recently demonstrated to activate distinct downstream transcriptional responses (93). Interestingly, through the use of optogenetic adenylate cyclase probes targeted to either plasma membrane, endosome or cytoplasm, these transcriptional responses were mediated entirely by the location of the cAMP signal (93), possibly suggesting that endosomally generated cAMP is “marked” by as yet unknown mechanisms for the cell to translate these events in to changes in expression of specific genes.

The spatial organization of second messenger signaling is likely to be important in a wider physiological context and for other GPCRs and G protein pathways. Indeed, sustained endosomal cAMP signaling has been also been reported for the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor with a requirement in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (94, 95), the V2 vasopressin receptor with roles in regulating renal water and sodium transport and the differential antidiuretic effect between vasopressin and OT (96), the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide type 1 receptor with roles in pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide-induced neuronal excitability (95) and potentially the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 in order to stimulate production of amyloid-β peptides that are involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (97).

Endosomal G protein signaling is also relevant for reproductive systems as has been demonstrated for the kisspeptin receptor, a Gαq/11-coupled GPCR that exhibits a persistent calcium signaling profile in CHO cells and the hypothalamic GnRH-expressing neuronal cell line GT1–7 (98). This persistent signal was entirely dependent on receptor internalization (98) and may in part underlie the enhanced activity of the R386P kisspeptin receptor mutation, which causes central precocious puberty, due to its decrease in receptor degradation/down-regulation and net increase in recycling, and potentially enhanced endosomal calcium signaling (99). Interestingly, this study also demonstrates that endosomal signaling from a GPCR can occur for additional G protein pathways.

Spatial regulation of GPCR signaling across divergent endosomes. The very EE (VEE)

Conventionally, the EE is viewed as both the earliest and primary platform for receiving, organizing, and sorting diverse sets of cargo. However, our recent work has demonstrated that 2 Gαs-coupled GPCRs, which undergo sequence-directed recycling, the β2AR, and the human LHR (rodent LHRs lack the recycling sequence and are primarily sorted for degradation) (100) are differentially sorted to distinct endosomal compartments. The β2AR is well known to rapidly internalize and sort from EEs. However, the LHR internalized to a physically smaller endosome compartment devoid of EE markers EE antigen 1 and phosphatidylinositol-3 phosphate. The endosomal size and biochemical content suggested the LHR internalizes to a distinct compartment upstream of the EE (101). It is known that a subpopulation of EE intermediates exist that are considered precursors of classic sorting endosomes and notably recruit the effector protein of the GTPase Ras-related protein Rab5, adaptor protein containing PH domain, PTB domain, and Leucine zipper motif (APPL1) (102). Although LHR was found to traffic to APPL-positive endosomes, this receptor does not require Rab5 for its activity, suggesting that the pre-EEs that LHR traffics to may be a distinct compartment (101). Routing of the LHR to this smaller pre-EE compartment was dependent on the receptor interacting with the PDZ protein Gαi-interacting protein C terminus (GIPC), which was previously shown to interact with the LHR carboxy-terminal tail and required for its recycling (103). These studies are complementary as a loss of this interaction inhibits LHR recycling due to the rerouting of this receptor away from pre-EEs to EEs. This indicated a sorting requirement for this compartment and hence may represent a VEE (Figure 1D). It also demonstrated that sequence-directed sorting of GPCRs can occur from compartments other than the EE, as has also been demonstrated recently for the β1AR (104).

The VEE also provided a mechanism for direct spatial control of GPCR signaling. LH-induced activation of the LHR induced a sustained temporal profile of ERK signaling that required both internalization and targeting to the correct endosomal compartment, the VEE (101). Thus, in addition to the compartmental bias in heterotrimeric G protein signaling between the plasma membrane and EEs described in the studies above, there is also compartmental bias in GPCR signaling across distinct endosomes. APPL endosomes have been shown to act as signaling centers to regulate the MAPK and Akt signaling cascades by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), adiponectin and tropomyosin receptor kinase A receptors and could be crucial for cell survival in some systems (105–109). For LHR, the downstream role of VEE targeting remains to be determined. However, LH does induce a sustained ERK signaling profile in human granulosa cells that negatively regulates aromatase expression (110), a signaling profile that may result from localization to and trafficking from VEEs. However, the known hyperandrogenemia that is one of the diagnostic hallmarks of PCOS may be a result of altered LHR endosomal location or retention in VEEs that could result in altered or enhanced signal profile leading to the known increased androstenedione production by LHR in theca cells (111, 112).

The VEE may be key in regulating activity for GPCRs in addition to the LHR, as has been shown for the β1AR and the FSHR (101). Although the β1AR is a known GIPC-interacting GPCR (113), the requirement of GIPC in FSHR signaling has not been reported, although APPL1 is a well-known binding partner of FSHR (114), and APPL1 and GIPC can also associate (108), suggesting a possible mechanism of VEE regulation by these GPCRs. Overall, the finding that distinct endosomes can confer defined spatial control of receptor signaling provides a cell system where hormonal signaling could be altered by simply rerouting receptors between compartments under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Spatial control of GPCR signaling is more than just an emerging concept but now a working cellular model (Figure 1) that now can be employed to understand how cells translate complex signaling responses into defined cellular programs in vivo. However, the molecular details of these pathways for a given receptor are likely to be even more complex. A detailed understanding of these fundamental cell biological mechanisms will likely accelerate with advances in imaging technology such as the broad spectrum of super-resolution microscopy approaches that are currently being employed, enabling visualization of proteins below the diffraction barrier of standard immunofluorescence microscopy, including TIRF-M, and even its adaptation to studying molecular processes directly in vivo (115).

GPCRs remain one of the most successful drug targets, and harnessing or manipulating the spatial control of GPCR signaling is already being targeted for novel therapeutic strategies. Biased ligands are of current high interest with some in clinical development (116, 117). Such compounds can stabilize a subset of multiple possible receptor conformations, leading to high selectivity in its action and potentially fewer off target effects. These ligands can target either orthosteric or allosteric binding sites in the receptor, or even intracellular regions of the receptor as shown recently through the use of intrabodies or pepducins (118–121). Currently, this pharmacological “tool box” targets signal bias between distinct G protein pathways or between G protein and arrestin-mediated signaling. As the mechanisms and physiological roles of spatial control of GPCR signaling are understood, current compounds could be further refined, to accommodate the new information on these pathways and/or represent a platform to screen for novel ligands with highly defined properties in directing receptor location and thus spatial changes in GPCR signaling. Furthermore, endogenous hormones could be biased ligands, such as the distinct glycosylation variants of human chorionic gonadotrophin and FSH that are known to have distinct biological activities (122, 123). In terms of pharmaceutical development in targeting reproductive-relevant receptors, a number of small molecule allosteric compounds to GnRHR, LHR, and FSHR have been developed (124, 125). Although the pharmacochaperone properties of some of these compounds, such as those to GnRHR, have been well described (126), the role of these small molecules in spatial control or biased signaling remains to be determined. In addition to drug design, the approach that is used to characterize GPCR mutations or polymorphisms must also be revised to incorporate these latest models of GPCR signaling, such as has been demonstrated with the A189V FSHR mutation (40) and the R386P kisspeptin receptor mutation, which causes central precocious puberty (99).

In summary, spatial organization and thus the cellular location of a GPCR, can program the multidimensionality of GPCR signaling into highly regulated and distinct signaling profiles, a property that is highly advantageous for dynamic hormone signaling. Efforts must now be directed to exploit this new information in order to provide important insight in to complex diseases and conditions such as PCOS, gonadotropin-dependent cancers and preterm labor, and improving therapeutic strategies that incorporates the full pleiotropic nature of these receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Genesis Research Trust.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Genesis Research Trust.

Footnotes

- AKAP

- A-kinase anchoring protein

- APPL1

- adaptor protein containing PH domain, PTB domain, and Leucine zipper motif

- β2AR

- β2-adrenergic receptor

- ARF

- ADP-ribosylation factor

- Cav

- caveolin

- CB1

- cannabinoid receptor type 1

- CCP

- clathrin-coated pit

- CCR5

- chemokine receptor type 5

- EE

- early endosome

- FSH

- follicle-stimulating hormone

- FSHR

- FSH receptor

- GIPC

- Gαi-interacting protein C terminus

- GnRHR

- GnRH gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

- GPCR kinase

- LH

- luteinizing hormone

- LHR

- LH receptor

- OT

- oxytocin

- OTR

- OT receptor

- PCOS

- polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PDZ

- postsynaptic density 95/disc large/zonula occludens-1

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PTHR

- PTH receptor

- TIRF-M

- total-internal reflection microscopy

- VEE

- very EE.

References

- 1. Scita G, Di Fiore PP. The endocytic matrix. Nature. 2010;463:464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durieux AC, Prudhon B, Guicheney P, Bitoun M. Dynamin 2 and human diseases. J Mol Med. 2010;88:339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanyaloglu AC, von Zastrow M. Regulation of GPCRs by endocytic membrane trafficking and its potential implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:537–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMahon HT, Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:517–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rao Y, Rückert C, Saenger W, Haucke V. The early steps of endocytosis: from cargo selection to membrane deformation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:75–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reiter E, Lefkowitz RJ. GRKs and β-arrestins: roles in receptor silencing, trafficking and signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Multifaceted roles of β-arrestins in the regulation of seven-membrane-spanning receptor trafficking and signalling. Biochem J. 2003;375:503–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. β-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kang DS, Tian X, Benovic JL. Role of β-arrestins and arrestin domain-containing proteins in G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;27:63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang DS, Tian X, Benovic JL. β-Arrestins and G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Methods Enzymol. 2013;521:91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cao TT, Mays RW, von Zastrow M. Regulated endocytosis of G-protein-coupled receptors by a biochemically and functionally distinct subpopulation of clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24592–24602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Zhuang X. Ligands for clathrin-mediated endocytosis are differentially sorted into distinct populations of early endosomes. Cell. 2006;124:997–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mundell SJ, Luo J, Benovic JL, Conley PB, Poole AW. Distinct clathrin-coated pits sort different G protein-coupled receptor cargo. Traffic. 2006;7:1420–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M. Cargo regulates clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Cell. 2006;127:113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McArdle CA, Franklin J, Green L, Hislop JN. Signalling, cycling and desensitisation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptors. J Endocrinol. 2002;173:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vrecl M, Heding A, Hanyaloglu A, Taylor PL, Eidne KA. Internalization kinetics of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:R19–R20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soohoo AL, Puthenveedu MA. Divergent modes for cargo-mediated control of clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1725–1734, S1721–S1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flores-Otero J, Ahn KH, Delgado-Peraza F, Mackie K, Kendall DA, Yudowski GA. Ligand-specific endocytic dwell times control functional selectivity of the cannabinoid receptor 1. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farkas I, Kalló I, Deli L, et al. Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling reduces GABAergic synaptic transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5818–5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pal K, Mathur M, Kumar P, DeFea K. Divergent β-arrestin-dependent signaling events are dependent upon sequences within G-protein-coupled receptor C termini. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3265–3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, et al. Distinct phosphorylation sites on the β(2)-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of β-arrestin. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lampe M, Pierre F, Al-Sabah S, Krasel C, Merrifield CJ. Dual single-scission event analysis of constitutive transferrin receptor (TfR) endocytosis and ligand-triggered β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) or Mu-opioid receptor (MOR) endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:3070–3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grove J, Metcalf DJ, Knight AE, et al. Flat clathrin lattices: stable features of the plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:3581–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dominguez F, Galan A, Martin JJ, Remohi J, Pellicer A, Simón C. Hormonal and embryonic regulation of chemokine receptors CXCR1, CXCR4, CCR5 and CCR2B in the human endometrium and the human blastocyst. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isobe T, Minoura H, Tanaka K, Shibahara T, Hayashi N, Toyoda N. The effect of RANTES on human sperm chemotaxis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barbonetti A, Vassallo MR, Antonangelo C, et al. RANTES and human sperm fertilizing ability: effect on acrosome reaction and sperm/oocyte fusion. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vogl AW, Du M, Wang XY, Young JS. Novel clathrin/actin-based endocytic machinery associated with junction turnover in the seminiferous epithelium. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adeoya-Osiguwa SA, Fraser LR. Cathine, an amphetamine-related compound, acts on mammalian spermatozoa via β1- and α2A-adrenergic receptors in a capacitation state-dependent manner. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:756–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Etkovitz N, Tirosh Y, Chazan R, et al. Bovine sperm acrosome reaction induced by G-protein-coupled receptor agonists is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. Dev Biol. 2009;334:447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shihan M, Bulldan A, Scheiner-Bobis G. Non-classical testosterone signaling is mediated by a G-protein-coupled receptor interacting with Gnα11. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of β-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by β-arrestins. Science. 2005;308:512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luttrell LM, Gesty-Palmer D. Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:305–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mukherjee S, Gurevich VV, Jones JC, et al. The ADP ribosylation factor nucleotide exchange factor ARNO promotes β-arrestin release necessary for luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor desensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5901–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salvador LM, Mukherjee S, Kahn RA, et al. Activation of the luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin hormone receptor promotes ADP ribosylation factor 6 activation in porcine ovarian follicular membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33773–33781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Breen SM, Andric N, Ping T, et al. Ovulation involves the luteinizing hormone-dependent activation of G(q/11) in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1483–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Galet C, Ascoli M. Arrestin-3 is essential for the activation of Fyn by the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1822–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Evaul K, Hammes SR. Cross-talk between G protein-coupled and epidermal growth factor receptors regulates gonadotropin-mediated steroidogenesis in Leydig cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27525–27533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tranchant T, Durand G, Gauthier C, et al. Preferential β-arrestin signalling at low receptor density revealed by functional characterization of the human FSH receptor A189 V mutation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;331:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grotegut CA, Feng L, Mao L, Heine RP, Murtha AP, Rockman HA. β-Arrestin mediates oxytocin receptor signaling, which regulates uterine contractility and cellular migration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E468–E477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brighton PJ, Rana S, Challiss RJ, Konje JC, Willets JM. Arrestins differentially regulate histamine- and oxytocin-evoked phospholipase C and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in myometrial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1603–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Terzidou V, Blanks AM, Kim SH, Thornton S, Bennett PR. Labor and inflammation increase the expression of oxytocin receptor in human amnion. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim SH, MacIntyre DA, Firmino Da Silva M, et al. Oxytocin activates NF-κB-mediated inflammatory pathways in human gestational tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;403:64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ahow M, Min L, Pampillo M, et al. KISS1R signals independently of Gαq/11 and triggers LH secretion via the β-arrestin pathway in the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4433–4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pike LJ. Lipid rafts: bringing order to chaos. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:655–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hiol A, Davey PC, Osterhout JL, et al. Palmitoylation regulates regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) 16 function. I. Mutation of amino-terminal cysteine residues on RGS16 prevents its targeting to lipid rafts and palmitoylation of an internal cysteine residue. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19301–19308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Monastyrskaya K, Hostettler A, Buergi S, Draeger A. The NK1 receptor localizes to the plasma membrane microdomains, and its activation is dependent on lipid raft integrity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7135–7146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pucadyil TJ, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol modulates ligand binding and G-protein coupling to serotonin (1A) receptors from bovine hippocampus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1663:188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Navratil AM, Bliss SP, Berghorn KA, et al. Constitutive localization of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor to low density membrane microdomains is necessary for GnRH signaling to ERK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31593–31602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bliss SP, Navratil AM, Breed M, Skinner DC, Clay CM, Roberson MS. Signaling complexes associated with the type I gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor: colocalization of extracellularly regulated kinase 2 and GnRH receptor within membrane rafts. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Navratil AM, Farmerie TA, Bogerd J, Nett TM, Clay CM. Differential impact of intracellular carboxyl terminal domains on lipid raft localization of the murine gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:788–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Navratil AM, Bliss SP, Roberson MS. Membrane rafts and GnRH receptor signaling. Brain Res. 2010;1364:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lei Y, Hagen GM, Smith SM, Barisas BG, Roess DA. Chimeric GnRH-LH receptors and LH receptors lacking C-terminus palmitoylation sites do not localize to plasma membrane rafts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wolf-Ringwall AL, Winter PW, Roess DA, George Barisas B. Luteinizing hormone receptors are confined in mesoscale plasma membrane microdomains throughout recovery from receptor desensitization. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;68:561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wolf-Ringwall AL, Winter PW, Liu J, Van Orden AK, Roess DA, Barisas BG. Restricted lateral diffusion of luteinizing hormone receptors in membrane microdomains. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29818–29827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dang AK, Murtazina DA, Magee C, Navratil AM, Clay CM, Amberg GC. GnRH evokes localized subplasmalemmal calcium signaling in gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:2049–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu F, Austin DA, Mellon PL, Olefsky JM, Webster NJ. GnRH activates ERK1/2 leading to the induction of c-fos and LHβ protein expression in LβT2 cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:419–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wehmeyer L, Du Toit A, Lang DM, Hapgood JP. Lipid raft- and protein kinase C-mediated synergism between glucocorticoid- and gonadotropin-releasing hormone signaling results in decreased cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10235–10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Franks S, Stark J, Hardy K. Follicle dynamics and anovulation in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Perrett RM, Voliotis M, Armstrong SP, et al. Pulsatile hormonal signaling to extracellular signal-regulated kinase: exploring system sensitivity to gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency and width. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7873–7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pike LJ. The challenge of lipid rafts. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(suppl):S323–S328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Song KS, Scherer PE, Tang Z, et al. Expression of caveolin-3 in skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle cells. Caveolin-3 is a component of the sarcolemma and co-fractionates with dystrophin and dystrophin-associated glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15160–15165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shvets E, Ludwig A, Nichols BJ. News from the caves: update on the structure and function of caveolae. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;29:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Oh P, Schnitzer JE. Segregation of heterotrimeric G proteins in cell surface microdomains. G(q) binds caveolin to concentrate in caveolae, whereas G(i) and G(s) target lipid rafts by default. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:685–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chini B, Parenti M. G-protein coupled receptors in lipid rafts and caveolae: how, when and why do they go there? J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;32:325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sengupta P, Philip F, Scarlata S. Caveolin-1 alters Ca(2+) signal duration through specific interaction with the G α q family of G proteins. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Whittington K, Connors B, King K, Assinder S, Hogarth K, Nicholson H. The effect of oxytocin on cell proliferation in the human prostate is modulated by gonadal steroids: implications for benign prostatic hyperplasia and carcinoma of the prostate. Prostate. 2007;67:1132–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Marchese A, Paing MM, Temple BR, Trejo J. G protein-coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:601–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yudowski GA, Puthenveedu MA, Henry AG, von Zastrow M. Cargo-mediated regulation of a rapid Rab4-dependent recycling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2774–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Seachrist JL, Anborgh PH, Ferguson SS. β 2-adrenergic receptor internalization, endosomal sorting, and plasma membrane recycling are regulated by rab GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27221–27228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cao TT, Deacon HW, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M. A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1999;401:286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lauffer BE, Melero C, Temkin P, et al. SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yudowski GA, Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M. Distinct modes of regulated receptor insertion to the somatodendritic plasma membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yu YJ, Dhavan R, Chevalier MW, Yudowski GA, von Zastrow M. Rapid delivery of internalized signaling receptors to the somatodendritic surface by sequence-specific local insertion. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11703–11714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jullié D, Choquet D, Perrais D. Recycling endosomes undergo rapid closure of a fusion pore on exocytosis in neuronal dendrites. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11106–11118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:959–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Logue JS, Scott JD. Organizing signal transduction through A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). FEBS J. 2010;277:4370–4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tao J, Shumay E, McLaughlin S, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Regulation of AKAP-membrane interactions by calcium. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23932–23944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shih M, Lin F, Scott JD, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Dynamic complexes of β2-adrenergic receptors with protein kinases and phosphatases and the role of gravin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1588–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tao J, Malbon CC. G-protein-coupled receptor-associated A-kinase anchoring proteins AKAP5 and AKAP12: differential signaling to MAPK and GPCR recycling. J Mol Signal. 2008;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. El-Jouni W, Haun S, Hodeify R, Hosein Walker A, Machaca K. Vesicular traffic at the cell membrane regulates oocyte meiotic arrest. Development. 2007;134:3307–3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Nishimura T, Fujii W, Sugiura K, Naito K. Cytoplasmic anchoring of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) by A-kinase anchor proteins (AKAPs) is required for meiotic arrest of porcine full-grown and growing oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hinckley M, Vaccari S, Horner K, Chen R, Conti M. The G-protein-coupled receptors GPR3 and GPR12 are involved in cAMP signaling and maintenance of meiotic arrest in rodent oocytes. Dev Biol. 2005;287:249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Calebiro D, Nikolaev VO, Gagliani MC, et al. Persistent cAMP-signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ferrandon S, Feinstein TN, Castro M, et al. Sustained cyclic AMP production by parathyroid hormone receptor endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:734–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Feinstein TN, Wehbi VL, Ardura JA, et al. Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:278–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gidon A, Al-Bataineh MM, Jean-Alphonse FG, et al. Endosomal GPCR signaling turned off by negative feedback actions of PKA and v-ATPase. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:707–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Okazaki M, Ferrandon S, Vilardaga JP, Bouxsein ML, Potts JT Jr, Gardella TJ. Prolonged signaling at the parathyroid hormone receptor by peptide ligands targeted to a specific receptor conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16525–16530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Irannejad R, Tomshine JC, Tomshine JR, et al. Conformational biosensors reveal GPCR signalling from endosomes. Nature. 2013;495:534–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Fung JJ, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the β(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tsvetanova NG, von Zastrow M. Spatial encoding of cyclic AMP signaling specificity by GPCR endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:1061–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kuna RS, Girada SB, Asalla S, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-mediated endosomal cAMP generation promotes glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E161–E170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Merriam LA, Baran CN, Girard BM, Hardwick JC, May V, Parsons RL. Pituitary adenylate cyclase 1 receptor internalization and endosomal signaling mediate the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide-induced increase in guinea pig cardiac neuron excitability. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4614–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Feinstein TN, Yui N, Webber MJ, et al. Noncanonical control of vasopressin receptor type 2 signaling by retromer and arrestin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:27849–27860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hoshino T, Namba T, Takehara M, et al. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates the production of amyloid-β peptides through internalization of the EP4 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18493–18502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Min L, Soltis K, Reis AC, et al. Dynamic kisspeptin receptor trafficking modulates kisspeptin-mediated calcium signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:16–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bianco SD, Vandepas L, Correa-Medina M, et al. KISS1R intracellular trafficking and degradation: effect of the Arg386Pro disease-associated mutation. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1616–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Galet C, Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. The postendocytotic trafficking of the human lutropin receptor is mediated by a transferable motif consisting of the C-terminal cysteine and an upstream leucine. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:434–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Jean-Alphonse F, Bowersox S, Chen S, Beard G, Puthenveedu MA, Hanyaloglu AC. Spatially restricted G protein-coupled receptor activity via divergent endocytic compartments. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:3960–3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A, et al. APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell. 2004;116:445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Hirakawa T, Galet C, Kishi M, Ascoli M. GIPC binds to the human lutropin receptor (hLHR) through an unusual PDZ domain binding motif, and it regulates the sorting of the internalized human choriogonadotropin and the density of cell surface hLHR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49348–49357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Koliwer J, Park M, Bauch C, von Zastrow M, Kreienkamp HJ. The Golgi-associated PDZ domain protein PIST/GOPC stabilizes the β1-adrenergic receptor in intracellular compartments after internalization. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(10):6120–6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Lin DC, Quevedo C, Brewer NE, et al. APPL1 associates with TrkA and GIPC1 and is required for nerve growth factor-mediated signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8928–8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Mao X, Kikani CK, Riojas RA, et al. APPL1 binds to adiponectin receptors and mediates adiponectin signalling and function. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Schenck A, Goto-Silva L, Collinet C, et al. The endosomal protein Appl1 mediates Akt substrate specificity and cell survival in vertebrate development. Cell. 2008;133:486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Varsano T, Dong MQ, Niesman I, et al. GIPC is recruited by APPL to peripheral TrkA endosomes and regulates TrkA trafficking and signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8942–8952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Zoncu R, Perera RM, Balkin DM, Pirruccello M, Toomre D, De Camilli P. A phosphoinositide switch controls the maturation and signaling properties of APPL endosomes. Cell. 2009;136:1110–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Casarini L, Lispi M, Longobardi S, et al. LH and hCG action on the same receptor results in quantitatively and qualitatively different intracellular signalling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Nelson VL, Legro RS, Strauss JF 3rd, McAllister JM. Augmented androgen production is a stable steroidogenic phenotype of propagated theca cells from polycystic ovaries. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:946–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Gilling-Smith C, Willis DS, Beard RW, Franks S. Hypersecretion of androstenedione by isolated thecal cells from polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1158–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hu LA, Chen W, Martin NP, Whalen EJ, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. GIPC interacts with the β1-adrenergic receptor and regulates β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26295–26301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Dias JA, Mahale SD, Nechamen CA, Davydenko O, Thomas RM, Ulloa-Aguirre A. Emerging roles for the FSH receptor adapter protein APPL1 and overlap of a putative 14–3-3τ interaction domain with a canonical G-protein interaction site. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;329:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Berning S, Willig KI, Steffens H, Dibaj P, Hell SW. Nanoscopy in a living mouse brain. Science. 2012;335:551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Khoury E, Clement S, Laporte SA. Allosteric and biased g protein-coupled receptor signaling regulation: potentials for new therapeutics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Carr R 3rd, Du Y, Quoyer J, et al. Development and characterization of pepducins as Gs-biased allosteric agonists. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35668–35684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Quoyer J, Janz JM, Luo J, et al. Pepducin targeting the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 acts as a biased agonist favoring activation of the inhibitory G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E5088–E5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Staus DP, Wingler LM, Strachan RT, et al. Regulation of β2-adrenergic receptor function by conformationally selective single-domain intrabodies. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Shukla AK. Biasing GPCR signaling from inside. Sci Signal. 2014;7:pe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Fournier T, Guibourdenche J, Evain-Brion D. Review: hCGs: different sources of production, different glycoforms and functions. Placenta. 2015;36(suppl 1):S60–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Jiang C, Hou X, Wang C, et al. Hypoglycosylated hFSH has greater bioactivity than fully glycosylated recombinant hFSH in human granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E852–E860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Yu HN, Richardson TE, Nataraja S, et al. Discovery of substituted benzamides as follicle stimulating hormone receptor allosteric modulators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:2168–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Heitman LH, Ye K, Oosterom J, Ijzerman AP. Amiloride derivatives and a nonpeptidic antagonist bind at two distinct allosteric sites in the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1808–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Conn PM, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Ito J, Janovick JA. G protein-coupled receptor trafficking in health and disease: lessons learned to prepare for therapeutic mutant rescue in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:225–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]