Abstract

Background

An estimated 2.4 billion people still lack access to improved sanitation and 946 million still practice open defecation. The World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned this review to assess the impact of sanitation on coverage and use, as part of its effort to develop a set of guidelines on sanitation and health.

Methods and findings

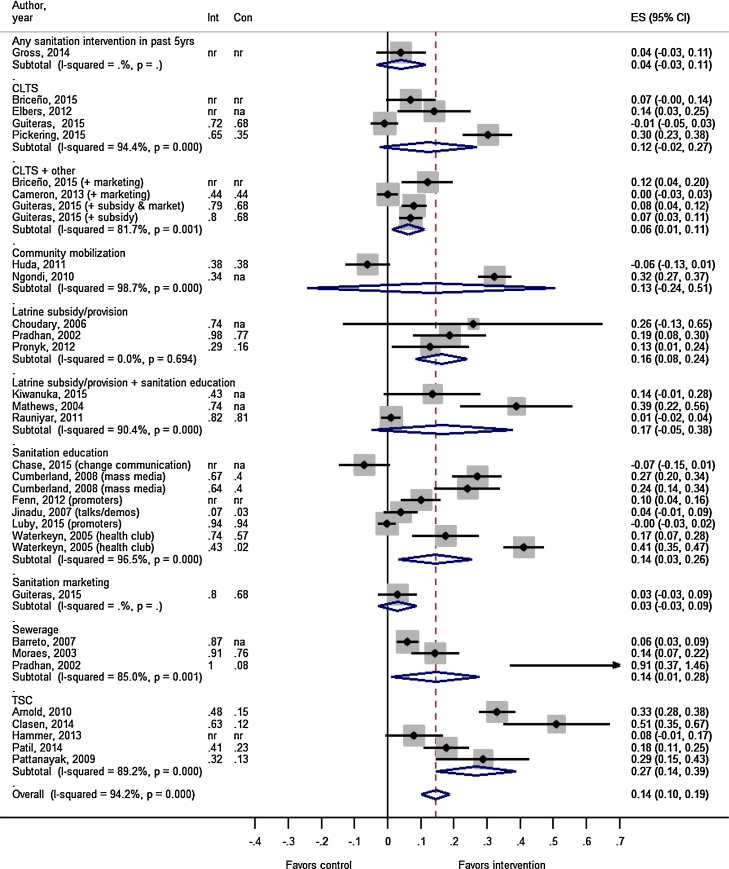

We systematically reviewed the literature and used meta-analysis to quantitatively characterize how different sanitation interventions impact latrine coverage and use. We also assessed both qualitative and quantitative studies to understand how different structural and design characteristics of sanitation are associated with individual latrine use. A total of 64 studies met our eligibility criteria. Of 27 intervention studies that reported on household latrine coverage and provided a point estimate with confidence interval, the average increase in coverage was 14% (95% CI: 10%, 19%). The intervention types with the largest absolute increases in coverage included the Indian government's “Total Sanitation Campaign” (27%; 95% CI: 14%, 39%), latrine subsidy/provision interventions (16%; 95% CI: 8%, 24%), latrine subsidy/provision interventions that also incorporated education components (17%; 95% CI: −5%, 38%), sewerage interventions (14%; 95% CI: 1%, 28%), sanitation education interventions (14%; 95% CI: 3%, 26%), and community-led total sanitation interventions (12%; 95% CI: −2%, 27%). Of 10 intervention studies that reported on household latrine use, the average increase was 13% (95% CI: 4%, 21%). The sanitation interventions and contexts in which they were implemented varied, leading to high heterogeneity across studies. We found 24 studies that examined the association between structural and design characteristics of sanitation facilities and facility use. These studies reported that better maintenance, accessibility, privacy, facility type, cleanliness, newer latrines, and better hygiene access were all frequently associated with higher use, whereas poorer sanitation conditions were associated with lower use.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that most sanitation interventions only had a modest impact on increasing latrine coverage and use. A further understanding of how different sanitation characteristics and sanitation interventions impact coverage and use is essential in order to more effectively attain sanitation access for all, eliminate open defecation, and ultimately improve health.

Keywords: Latrine use, Latrine coverage, Sanitation, Sanitation uptake

1. Introduction

It is estimated that 2.4 billion people still lack access to improved sanitation and 946 million still practice open defecation (UNICEF and WHO, 2015). A further understanding of how sanitation interventions and sanitation characteristics impact latrine coverage and use is essential in order to more efficiently work towards the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring access to sanitation for all by 2030 (2015). Securing high coverage and use of latrines is the foundation of an effective sanitation strategy. It is not clear, however, which sanitation interventions will best increase latrine coverage and use, or which sanitation characteristic are most likely to lead to existing latrines being used.

There is both long-standing biological plausibility and general acceptance in the health and development community that sanitation is important for health (Ferriman, 2007, Wagner and Lanoix, 1958). However, a number of recent rigorous sanitation trials have found either no impact or a mixed impact of the sanitation interventions on various health outcomes (Arnold et al., 2010, Briceño et al., 2015, Clasen et al., 2014, Fenn et al., 2012, Patil et al., 2014, Pickering et al., 2015). One possibility for the mixed success of these trials is that they may not have adequately increased latrine coverage and/or latrine use to the necessary thresholds required to reduce exposure to fecal pathogens and improve health. Previous interventions have varied in their emphasis of hardware (e.g. latrine construction or subsidies for construction), software (e.g. human-centered sanitation training, promotion, or marketing), or of unique combinations of hardware and software together. However, it is not clear which types of interventions will best improve coverage and use, or how to better implement interventions in order to reach the coverage thresholds required to improve health.

Even when high latrine coverage levels are achieved, open defecation is often still practiced (Barnard et al., 2013). Users may still choose to openly defecate, and that decision is likely influenced by a number of technological and behavioral factors (Coffey et al., 2014, Hulland et al., 2015, Routray et al., 2015). We were only able to find one report that reviewed factors associated with sanitation adoption (Hulland et al., 2015). That systematic review was primarily descriptive (no meta-analysis) and focused primarily on sustained adoption (e.g. whether latrine coverage persisted over time) and not on the initial increases in coverage due to the implementation of a specific intervention. The focus was also primarily on behavioral factors and strategies that impact behavior. We were unable to find any quantitative synthesis characterizing the impact of different sanitation interventions on coverage, or characterizing how structural and design characteristics of sanitation are associated with latrine use.

As part of its effort to develop guidelines on sanitation and health, the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned this systematic review to assess the impact of sanitation on coverage and use. Other WHO-commissioned reviews address the impact of sanitation on exposure pathways (Sclar et al., 2016), infectious disease and malnutrition (Freeman et al., submitted) and other outcomes that impact human wellbeing (Sclar et al., unpublished). Our study relates to the other reviews in that it forms the starting-point—sanitation interventions must increase coverage and use in order to decrease exposure and subsequently achieve health and well-being gains. Our review has several aims. Our primary objective was to characterize the impacts of various sanitation interventions on latrine coverage and also on latrine use. As a secondary objective we explored how various structural and design characteristics of sanitation (e.g. smell, presence of a door, etc.) were reported to be associated with use of latrines.

2. Methods

2.1. Study eligibility

A protocol was developed a priori and is available upon request. To assess our primary objective, to characterize how different sanitation intervention types impact latrine coverage and use, we used only studies that directly implemented a sanitation intervention. The study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs); non-randomized controlled studies such as quasi-RCTs, non-randomized controlled trials, and controlled before-and-after studies; and uncontrolled before and after studies. To assess our secondary aim, to understand how different structural and design sanitation characteristics were associated with individual latrine use, we used all design types, including both experimental and observational designs and both qualitative and quantitative studies. Our review covered various interventions types, including those providing subsidies, facilities or other hardware (e.g., household latrines, sewer connections), or the education and promotion of practices (e.g., discouraging open defecation). Interventions that combine sanitation with other interventions, such as improvements to water supply or water quality or promotion of hygiene or broader development interventions, were also included in the review, with an emphasis on the study arms that included sanitation components. The vast majority of our studies assessed latrine technologies rather than flush toilet technologies, so for simplicity we often use the phrases “latrine coverage” and “latrine use” to encapsulate coverage and use of all different types of sanitation technologies.

2.2. Search and study selection

This review includes literature published between 1950 and December 31, 2015. We attempted to minimize reporting bias by including studies published in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German or Italian and by carrying out a comprehensive search strategy that included published, unpublished, in press and grey literature. The search string was: ((feces OR faeces) AND sanitation) AND (use or coverage or community or utilization or indicators or household or household characteristics). We searched the following electronic databases: British Library for Development Studies, Campbell Library, clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, EBSCO (CINHAL, PsychInfo), LILACS, POPLINE, ProQuest, PubMed, Research for Development, Sanitary Engineering and Environmental Sciences (REPIDISCA), Social Science Research Network (SSRN), Sustainability Science Abstracts (SAS), Web of Science, and 3ie International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. We also searched the following organizations’ conference proceedings and websites: Carter Center, Center for Disease Control and Prevention Global WASH, International Water Association, Menstrual Hygiene Management in WASH in Schools Virtual Conference, Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm World Water Week Conference, University of North Carolina Water and Health Conference, UNICEF Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, UNICEF WASH in Schools, USAID Environmental Health Project, WASHplus, World Bank Water and Sanitation Program. We hand searched references of other systematic and narrative reviews that came out of the database and website searches of all included studies. Finally, we included relevant studies that were found during the database search of the other sanitation systematic reviews (Freeman et al., 2013a, Freeman et al., 2013b; Sclar et al., 2016; Sclar et al., unpublished).

One reviewer screened out non-relevant titles and then two reviewers independently examined the abstracts to determine if studies fell within the inclusion criteria for the review. Whenever a title or abstract could not be rejected with certainty, the full text was obtained for further screening. A third reviewer compared the abstract screenings and resolved any discrepancies in the eligibility decisions. The full text was then obtained for the remaining studies and two researchers then independently determined if those manuscripts met the inclusion criteria. Again, a third reviewer compared the full text screenings of the two reviewers and if there was disagreement on whether to include or exclude a manuscript, the third reviewer made the final decision.

2.3. Data extraction

Two extractors then independently extracted data from the selected studies and contacted authors of studies when additional data was needed (see Supplementary Text S1 for data extraction sheet). For study outcomes, we extracted the mean differences (or difference in differences) in coverage/use between intervention and control and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When the mean difference was not available, we calculated the difference based on raw numbers, or based on the prevalences reported by the authors, and calculated 95% CIs wherever possible. We also extracted the baseline and endline prevalence of sanitation coverage in each group. Coverage was defined as the proportion of households in a community with access to latrines or with connections to sewerage. Latrine use definitions were often less well-defined, with studies measuring either use or open defecation through self-report, observation, documented with sensors (e.g. PLUMS), or by observation of fecal indicators (e.g., presence of anal cleansing materials, wet slab, feces on the ground). Whenever a study reported open defecation instead of use, we used the inverse (e.g. percentage not openly defecating) as our measure of use, to increase comparability.

2.4. Assessment of bias & quality of evidence

Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias present in each study using an adapted version of the Liverpool Quality Appraisal Tool (LQAT) (Pope et al., unpublished). We used the LQAT due to the tool’s flexibility in both modifying exposure and outcome assessment and allowing for different study designs. The LQAT examines eight different areas of bias: selection bias, response rate bias, allocation bias, follow-up bias, bias in exposure assessment, bias in outcome assessment, bias in ascertainment, and confounding in analysis (see Supplementary Text S1 for LQAT extraction sheet). LQAT scores from each reviewer were compared and, if necessary, another researcher was consulted to resolve any discrepancies. We only considered quantitative studies that evaluated a sanitation intervention for the risk of bias assessment, since the LQAT is not an appropriate tool for qualitative study designs.

One researcher then examined the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome across all included studies using the GRADE approach, which considers risk of bias score, indirectness, inconsistency, lack of precision and publication bias (Guyatt et al., 2011a). When using GRADE, if the body of evidence is made up of RCTs then the GRADE score starts at ‘high’ but if the included studies are observational, then the score starts at ‘low.’ Since all of the included studies were primarily RCTs and controlled intervention studies, we started at a score of ‘high’ and downgraded accordingly for each assessment criteria; none of the three criteria for upgrading (i.e. size of effect, dose-response relationship, direction of residual confounding) could be applied to the included body of evidence. We downgraded for risk of bias if the body of evidence had an average LQAT score below 8. Indirectness refers to the lack of generalizability of the evidence to the review's specific research question of interest. Our research question was broad in scope, considering any geographical setting and a variety of sanitation interventions. Since the included studies met this desired breadth and all measured latrine coverage or use as an outcome, we did not downgrade for indirectness. We downgraded for inconsistency when the point estimates across the included studies differed in their direction or effect. When meta-analysis was possible, statistical heterogeneity was also considered during the inconsistency assessment, and we downgraded when a visual examination of the forest plot confidence intervals showed a lack of overlap (i.e. ‘Eye ball test’) and when there was an estimate of I2 > 70% and Chi2 p-value < 0.05 for the pooled effect estimate. We downgraded for lack of precision when the pooled effect estimate from the meta-analysis or the individual effect estimates were not statistically significant. Finally, publication bias was assessed by visually examining the level of symmetry in the corresponding funnel plots and through consideration of various sources of publication bias as described by Guyatt et al. (2011b) (see Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). A summary of findings table with corresponding GRADE scores is presented in Table 1 with the primary outcomes being change in sanitation coverage and change in sanitation use (see Supplementary Table S1 for additional details on the GRADE assessment for quality of evidence).

Table 1.

Summary of findings table for the impact of sanitation on latrine coverage and latrine use.

| Outcomes | N studies | Absolute difference (95% CI) | Quality of Evidence (GRADE)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household based studies | |||

| Change in latrine coverage | 27a | 14% (10%, 18%) | Low to Very Lowb |

| Change in latrine use | 10a | 13% (5%, 21%) | Low |

| School-based studies | |||

| Change in pupil to latrine ratios | 4 | −14 unit decrease in pupils per latrine (confidence intervals not estimatable) | Low to Very Low |

| Change in latrine use | 4 | Inconsistent reporting; Mixed results | Low to Very Low |

An additional nine studies assessing coverage and one study assessing use either did not include a measure of variation or had control groups that received a different type of sanitation interventions and as a result were not included in the meta-analyses.

The GRADE scores indicate that the quality of evidence for each outcome is primarily low to very low, which means we have very little confidence in the pooled effect estimates (i.e. the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect).

2.5. Synthesis of results

For our primary objective we used meta-analyses to pool estimates of the absolute change in latrine coverage and also latrine use across all intervention types. In view of substantial heterogeneity in populations, interventions, and study designs, random-effects models were used to pool across all sanitation interventions together and also across subgroups of comparable sanitation intervention types. The sanitation intervention sub-group categories were defined post-hoc based on similarities in the intervention characteristics as they were described in the extracted papers. The comparisons made were between those with the intervention and those without or with a different intervention or the intervention’s baseline value. Forest plots were used to present findings. In cases where the studies were not similar enough to pool together, we report individual study results displayed on the forest plot. Statistical heterogeneity was reported using the I2 statistics described above. We also performed several exploratory subgroup analyses. We performed meta-regression assessing the associations between latrine coverage and length of follow-up, level of coverage in the control group (or the level at baseline if no control group was present), or whether the study was controlled (vs. pre-post). Where associations were found with any of these variables, we present forest plots stratifying by the variable of interest. We performed all analyses in STATA 14 (College Station, TX, USA).

To assess our secondary aim, we tabulated various factors that were reported or observed to be associated with latrine use, organized the factors into key themes or ‘main factors’, and denoted with an arrow the direction of the association.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible studies

The initial search yielded 2264 titles and abstracts that were screened for eligibility, and then 625 full-texts assessed for eligibility. Of these, a total of 64 studies met our eligibility criteria and were extracted (Fig. 1). Out of the extracted studies, 37 were household-based intervention studies that assessed how different sanitation interventions impacted latrine coverage and/or use (Fig. 1; Table 1). These studies took place in various countries throughout Africa, Asia, and South America (Table 2). These included 36 household-based studies reporting on coverage and 11 household studies reporting on use. There were 4 eligible school based interventions (reported across 7 papers) that assessed the impact on pupil to latrine ratio (Table 3), and there were 4 studies that assessed use, with one common study assessing both pupil to latrine ratio and use. Another 24 studies examined how structural and design characteristics of sanitation were associated with latrine use.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of publications considered in this review.

Table 2.

The impact of sanitation interventions on household latrine coverage and/or use, organized by intervention description.

| References | Intervention Description | Country | Follow-up | Study Design | Latrine Coverage |

Latrine Use |

Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int. | Con. | Δa | Int. | Con. | Δa | definition | |||||

| Gross and Günther (2014) | Exposure to any sanitation project in last 5 years | Benin | 1–5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | nr | nr | 4% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Briceño et al. (2015) | CLTS + hand-washing | Tanzania | 3 yr. | RCT | nr | nr | 7% | nr | nr | 9% | HH does not (always or regularly) practice OD |

| CLTS + sanitation marketing | Tanzania | 3 yr. | RCT | nr | nr | 12% | 89% | nr | 10% | ||

| Cameron et al. (2013) | CLTS + marketing | Indonesia | 2 yr. | RCT | 44% | 44% | 0% | 66% | 64% | 2% | HH does not (normally) practice OD |

| Elbers et al. (2012) | CLTS | Mozambique | 2 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | nr | nr | 14% | nr | na | 12% | Unspecified “Use of latrines” |

| Guiteras et al. (2015) | CLTS-like Latrine Promotion Program (LPP) | Bangladesh | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 72% | 68% | −1% | 67% | 60% | 2% | HH does not openly defecate or use hanging toilet |

| CLTS-like LPP + latrine subsidy | Bangladesh | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 80% | 68% | 7% | 74% | 60% | 9% | ||

| CLTS-like LPP + latrine subsidy + supplies market | Bangladesh | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 79% | 68% | 8% | 73% | 60% | 9% | ||

| Harvey (2011) | CLTS (pilot data) | Zambia | 0.25 | Before-and-after | 88% | na | 65% | nr | na | nr | na |

| CLTS (follow-up study data) | Zambia | 0.75 | Before-and after | 93% | na | 55% | nr | na | nr | na | |

| Kullman et al. (2011) | CLTS vs. non CLTS NGO | Bangladesh | 4–5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 51% | 51% | 0% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Pickering et al. (2015) | CLTS | Mali | 1.5 yr. | RCT | 65% | 35% | 30% | 78% | 44% | 33% | No reported OD (by men, women, and children) |

| Sah and Negussie (2009) | CLTS | Eastern and Southern Africa | 0.25 yr. | Before-and-after | 93% | na | 49% | nr | na | nr | na |

| Whaley and Webster (2011) | CLTS vs. health clubb | Zimbabwe | 2 yr. | Non-randomized CT | 95% | 98% | −3% | 63% | 51% | 12% | Latrine used and clean |

| Huda et al. (2012) | Community mobilization (Community hygiene promoters led WASH mobilization) | Bangladesh | 1.5 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 38% | 38% | −6% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Kullman et al. (2011) | Community mobilization (Gov’t intervention + donor vs. Gov’t w/out donor) | Bangladesh | 4–5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 58% | 53% | 5% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Ngondi et al. (2010) | Community mobilization (sanitation training, education & construction demonstrations) | Ethiopia | 3 yr. | Before-and-after | 34% | na | 32% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Choudhury and Hossain (2006) | Latrine subsidy/provision | Bangladesh | 3 yr. | Before-and-after | 74% | na | 26% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Pradhan and Rawlings (2002) | Latrine subsidy/provision | Nicaragua | 7 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 98% | 77% | 19% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Pronyk et al. (2012) | Latrine provision as part of multi-faceted development project addressing MDGs | Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 29% | 16% | 13% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Simms et al. (2005) | Latrine provision | The Gambia | 2–4 yr. | Before-and-after | 95% | na | 63% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Ahmed et al. (2010) | Latrine provision + education | Bangladesh | 0.5 yr. | Before-and-after | 60% | na | 28% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Kiwanuka et al. (2015) | Latrine subsidy/provision + sanitation education | Uganda | 10 yr. | Before-and-after | 43% | na | 14% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Mathews and Kumari (2004) | Latrine subsidy/provision + sanitation education | India | 2–14 yr. | Before-and-after | 75% | na | 39% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Rauniyar et al. (2011) | Sanitation assistance + hygiene education + water supply | Pakistan | 6–13 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 82% | 81% | 1% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Chase et al. (2015) | Sanitation education (behavior change communication) | Cambodia | 1 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | nr | nr | −7% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Cumberland et al. (2008) | Sanitation education (mass media + video) | Ethiopia | 3 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 67% | 40% | 27% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Sanitation education (mass media) | Ethiopia | 3 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 64% | 40% | 24% | nr | nr | nr | na | |

| Fenn et al. (2012) | Sanitation education + water supply | Ethiopia | 5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | nr | nr | −1% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Sanitation education + water supply + nutrition/health education + drugs | Ethiopia | 5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | nr | nr | 10% | nr | nr | nr | na | |

| Jinadu et al. (2007) | Sanitation education (focused on safe disposal of child feces) | Nigeria | 1 yr. | RCT | 7% | 3% | 4% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| King et al. (2013) | Sanitation education (Latrine promotion + hygiene education) | Ethiopia | 8–11 yr. | Before-and-after | 42% | na | 39% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Luby (2015) | Sanitation education (health promoters) | Bangladesh | 1 yr. | RCT | 94% | 94% | 0% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Murthy et al. (1990) | Sanitation education (mass media) | India | 0.5 yr. | Before-and-after | nr | nr | nr | 67% | na | 6% | Exclusive use of community latrine |

| Saowakontha et al. (1993) | Sanitation education (motivation on construction and use + chemotherapy) | Thailand | 3 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 58% | 78% | −20% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Sanitation education (motivation on construction and use + intensive chemotherapy) | Thailand | 3 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 75% | 78% | −3% | nr | nr | nr | na | |

| Waterkeyn and Cairncross (2005) | Sanitation education (community health club; place A) | Zimbabwe | 2 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 43% | 2% | 41% | 41% | 2% | 39% | Used a clean latrine |

| Sanitation education (community health club; place B) | Zimbabwe | 2 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 74% | 57% | 17% | 38% | 31% | 7% | ||

| Devine and Sijbesma (2011) | Sanitation marketing | Vietnam | 5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 59% | 39% | 20% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Guiteras et al. (2015) | Supplies market only | Bangladesh | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 80% | 68% | 3% | 73% | 60% | 3% | HH does not openly defecate or use hanging toilet |

| Barreto et al. (2007) | Sewerage | Brazil | 6 yr. | Before-and-after | 87% | na | 6% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Moraes et al. (2003) | Sewerage | Brazil | >5 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 91% | 77% | 14% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Pradhan and Rawlings (2002) | Sewerage | Nicaragua | 7 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 100% | 9% | 91% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Arnold et al. (2010) | TSC-like | India | 5 yr. | Controlled before-and-after | 48% | 15% | 33% | 23% | 12% | 11% | HH does not practice OD |

| Clasen et al. (2014) | TSC | India | 3 yr. | RCT | 63% | 12% | 51% | 36% | 9% | 27% | Functional latrine and signs of present use |

| Hammer and Spears (2013) | TSC | India | 1.5 yr. | RCT | nr | nr | 8% | nr | nr | nr | na |

| Patil et al. (2014) | TSC | India | 2 yr. | RCT | 41% | 23% | 18% | 27% | 17% | 9% | HH using individual household latrine |

| Pattanayak et al. (2009) | TSC + intensified IEC | India | 1 yr. | RCT | 32% | 13% | 29% | nr | nr | nr | na |

Int.= Mean prevalence of coverage or use in the intervention arm. Con. = Mean prevalence of coverage or use in the control arm. na = not applicable (e.g. before-and-after studies did not have separate control groups). nr = not reported.

Some differences do not line up with the reported prevalences because we extracted the most-adjusted results from each paper (i.e. difference-in-difference).

Control group also received a different sanitation intervention.

Table 3.

The impact of school-based sanitation interventions on school pupil to latrine ratio.

| Reference | Intervention details | Country | Follow-up | Study Design | Pupil to latrine ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int. | Con. | Δ | |||||

| Freeman et al. (2014) | Comprehensive WASH | Kenya (water available schools) | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 41 | 51 | −10 |

| Comprehensive WASH + water supply | Kenya (water scarce schools) | 1–2 yr. | RCT | 36 | 61 | −25 | |

| Trinies et al. (2016) | Comprehensive WASH | Mali | 1 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 59 | 108 | −49 |

| Mathew et al. (2008) | Comprehensive WASH | India (district A) | 4 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 98 | 82 | 10 |

| India (district K) | 58 | 82 | −24 | ||||

| Njuguna et al. (2008) | Comprehensive WASH | Kenya (girls) | 1–16 yr. | Nonrandomized CT | 37 | 41 | −4 |

| Kenya (boys) | 59 | 55 | 4 | ||||

Int. = Mean school pupil to latrine ratio in the intervention arm. Con. = Mean school pupil to latrine ratio in the control arm.

3.2. Impacts of sanitation on coverage/use

The main results of this review are summarized in the summary of findings table (Table 1). These are discussed in further detail in the following sections.

3.3. Household based studies assessing coverage and use

Most of the 36 household-based studies assessing sanitation interventions on latrine coverage showed point estimates with increased coverage due to the intervention, regardless of the intervention strategy (Table 2). Two studies were not eligible to be included in the coverage meta-analyses because these studies had control groups that received a different type of sanitation interventions, (Kullman et al., 2011, Whaley and Webster, 2011) and another seven studies were not included as they did not report adequate information to be able to extract or calculate a confidence interval (Ahmed et al., 2010, Fenn et al., 2012, Harvey, 2011, King et al., 2013, Sah and Negussie, 2009, Saowakontha et al., 1993, Simms et al., 2005); 27 studies remained eligible to be included in the coverage meta-analysis (Fig. 2). Across these 27 studies, the intervention arm had an average increase in latrine coverage of 14% (95% CI: 10%, 19%), compared to the control. Several interventions were found to have had moderate increases in coverage, including the Indian government's “Total Sanitation Campaign” (TSC) (27%; 95% CI: 14%, 39%), latrine subsidy/provision interventions (16%; 95% CI: 8%, 24%), sewerage interventions (14%; 95% CI: 1%, 28%), and sanitation education interventions (14%; 95% CI: 2%, 26%). Other intervention types had moderate, but not statistically significant impacts including latrine subsidy/provision interventions that also incorporated education components (17%; 95% CI: −5%, 38%), and Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) interventions (12%; 95% CI: −2%, 27%). CLTS interventions when combined with some other intervention had a small impact on latrine coverage (6%; 95% CI: 1%-11%). We point out that the estimates for CLTS and for latrine subsidy/provision are likely to be underestimates because two CLTS studies (Harvey, 2011, Sah and Negussie, 2009) and one latrine subsidy/provision study (Simms et al., 2005) were unable to be included due to inadequate reporting of a measure of variation and each of these studies had estimates well above the mean. Sensitivity analyses showed that including these missing studies to calculate an unweighted mean produces an estimated change in coverage of 31% for the CLTS interventions and of 30% for the subsidy/provision interventions.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the impact of different sanitation interventions on latrine coverage. Int = Mean prevalence of latrine coverage in the intervention arm. Con = Mean prevalence of latrine coverage in the in control arm. na = not applicable (i.e. pre-post study design). nr = not reported.

Meta-regression analyses indicated a significant decrease in the impact of the sanitation interventions with higher levels of coverage in the control/baseline group (p-value < 0.01), but no association with length of follow-up (p-value = 0.17), or having a controlled study (compared to a pre-post study; p-value = 0.89). Studies with coverage levels in the control/baseline group greater than 50% had the smallest increases in endline coverage (See supplementary Fig. S3).

Far fewer of these studies actually assessed latrine use (N = 11; Fig. 3; Table 2). All of these studies, regardless of the intervention strategy, had point estimates showing increased latrine use due to the intervention. We were able to extract or calculate both a point estimate and a measure of variation from 10 of these studies and, from these, the intervention arm had an average increase in latrine use of 13% (95% CI: 4%, 21%), compared to the control. Among those studies reporting both latrine coverage and latrine use, a post hoc regression analysis indicated that for each 10% increase in latrine coverage there was a 5.8% increase in latrine use (Beta = 0.58 95% CI: 0.30, 0.80; p < 0.01). The small sample size did not allow for further stratification by sanitation intervention type, although it appears that for TSC studies, the populations’ increases in latrine use were not commensurate with their increases in latrine coverage.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the impact of different sanitation interventions on latrine use. Int = Mean prevalence of use by study participants in intervention arm. Con = Mean prevalence of use by study participants in control arm. na = not applicable (i.e. pre-post study design). nr = not reported.

3.4. School-based studies assessing coverage and use

We found 4 unique interventions that assessed school-based comprehensive WASH interventions and their impacts on coverage, as measured by pupil-to-latrine ratios (Table 3) (Freeman et al., 2014, Mathew et al., 2008, Njuguna et al., 2008, Trinies et al., 2016). We were unable to meta-analyze these school-based studies because they often did not provide CIs around their estimates (or standard errors). These studies reported an average decrease of 14 units in pupils per latrine (range: −49, 10) due to the intervention. The studies by Freeman et al. (2014) and by Trinies et al. (2016) both found reductions in pupil to latrine ratio due to the interventions (range: −49, −10), whereas the studies by Mathew et al. (2008) and Njuguna et al. (2008) only observed reductions among some subgroups (range: −24, 10). Freeman et al. (2014) and Trinies et al. (2016) measured pupil-to-latrine ratios within two years of implementation of the intervention, whereas (Mathew et al., 2008) and (Njuguna et al., 2008) assessed long-term sustainability over many years (e.g. between 1 and 16 years) and also had much more variation in their within study intervention strategies.

Only four studies assessed how school-based sanitation interventions affected the actual use of latrines at those schools. Mathew et al. (2008) observed that their comprehensive school WASH interventions did not increase household-based latrine use in the previous week. Gyorkos et al. (2013) observed that a school-based sanitation education intervention did not have a significant impact on pupils’ open defecation behaviors. Garn et al. (2014) found a strong relationship between decreasing pupil to toilet ratio and increasing toilet use, using observational data nested within a larger trial. Caruso et al. (2014b) observed similar latrine use among pupils in an intervention arm that received latrine cleaning supplies compared to pupils in a control arm. This study was only included in the latrine use analysis and not the coverage analysis, as the sanitation intervention was not focused on increasing latrine coverage, but was explicitly targeted to increase latrine use.

3.5. Sanitation structure and design characteristics and their associations with latrine use

We found 24 household- and school-based studies that assessed the associations between sanitation structure/design characteristics and latrine use (Table 4). Nearly all of these studies were observational or qualitative studies. Better latrine maintenance, accessibility, privacy, latrine type, cleanliness, newer latrines, and access to hygiene amenities were usually associated with higher latrine use, whereas poorer sanitation conditions were usually associated with lower use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sanitation structure and design characteristics and their associations with latrine use.

↓= increased use; ↑ = decreased use.

4. Discussion

Various rigorous sanitation intervention studies have focused on the impacts of intervention on health and nutrition, and a number of these studies have showed little if any health impact from sanitation interventions (Arnold et al., 2010, Barreto et al., 2007, Briceño et al., 2015, Cameron et al., 2013, Clasen et al., 2014, Dreibelbis et al., 2014, Fenn et al., 2012, Freeman et al., 2013a, Freeman et al., 2013b, Freeman et al., 2014, Hammer and Spears, 2013, Jinadu et al., 2007, Moraes et al., 2003, Patil et al., 2014, Pickering et al., 2015, Pradhan and Rawlings, 2002). For this reason, there is a need to focus on whether interventions are succeeding in securing significant increases in latrine coverage and use—the basic antecedents necessary to reduce exposure and deliver health gains. Our study is the first to quantitatively characterize which sanitation interventions increase latrine coverage and latrine use, and factors associated with higher use of latrines.

We found that many different types of household-based sanitation interventions that increased latrine use, including TSC, latrine subsidy/provision interventions, other latrine subsidy/provision interventions that also incorporated education components, sewerage interventions, sanitation education interventions, and CLTS interventions. The school based comprehensive WASH studies that included latrine provisions also showed improvements in pupil to latrine ratios. Of the interventions that assessed latrine use, all had point estimates showing increased latrine use due to the intervention. However, latrine coverage did not always translate into equal increases in latrine use. Finally, we found many studies that indicated people are more likely to use a latrine when they are functional, well maintained, accessible, clean, private, and provide amenities for practicing hygienic behaviors like anal cleaning and menstrual management. These structure and design characteristics that are associated with increased latrine use could be used to define what it means to have adequate sanitation—sanitation that meets the needs of the user.

The interventions ‘impact on increasing latrine coverage depended upon the baseline prevalence of latrine coverage. Across all of our studies, communities with the largest coverage gains often had the lowest baseline coverage levels, which may seem mathematically probable as higher starting coverage level also constrains the absolute increase in coverage to be smaller as there is less room for improvement. Indeed, many of the studies among communities with higher baseline coverage levels had more difficulty making appreciable progress towards increased coverage (Table S3), suggesting some interventions are simply more tailored for communities with lower baseline coverage levels. Guiteras et al. (2015) had a high baseline coverage level of 78% and were the only CLTS-like study with a decrease in latrine coverage one year after receiving the intervention. They reported that the CLTS-like latrine promotion program was not effective without a concurrent subsidy (Guiteras et al., 2015). Furthermore, a community’s previous experience with sanitation subsidy interventions was a negative contributor to the effectiveness of their current non-subsidy interventions. For example, Harvey (2011)—the study with the largest coverage increase for CLTS interventions (Table 2)—reported that CLTS was least effective in communities where subsidies had already been given to the community members. They reported that villages with the highest initial coverage made the least progress, and it was hypothesized that this was because they had experienced previous hardware subsidies.

Another context-specific finding is that no-subsidy interventions may be less successful in settings where building materials are not so readily available or where knowledge of the construction process is not ubiquitous. Pickering et al. (2015) found that CLTS increased latrine coverage in Mali, but they note that the construction materials (clay, sand, water, grain husks) were locally available and construction practices were familiar and similar to what was used to build residences. Malebo et al. (2012) similarly reported that having affordable toilet technologies and locally available materials and laborers was important. These cost and availability considerations may be particularly important for no-subsidy interventions, and may be primary reasons for varied success across CLTS studies and across market-based studies.

Most of the papers we found assessed the initial impacts of the interventions on coverage or use, and not sustained adoption or ‘slippage’ of interventions. Sustained adoption has been reviewed by Hulland et al. (2015) elsewhere. They found “the most influential programme factors associated with sustainability include frequent, personal contact with a health promoter and accountability over a period of time. Personal follow-up in conjunction with other measures like mass media advertisements or group meetings may further increase sustained adoption.” We did find some papers on this topic. Kullman et al. (2011) found minimal slippage after 4.5 years of being declared open defecation free (only 2.5% didn’t have access to any sanitation), and that the original intervention type didn’t matter. Devine and Sijbesma (2011) found that coverage increased after the program was completed, suggesting either the intervention had persistent effects or that outside forces were driving the increases.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our study had several limitations. While most of these studies reported coverage, there was inconsistent reporting of use. The meta-analysis measuring the impact of sanitation interventions on latrine use should be interpreted cautiously, as latrine use was often defined in different ways across these studies, and as the latrine use measures were often self-reported, and therefore subject to respondent biases. The LQAT scores for the majority of studies indicated some risk of bias while the GRADE assessment indicated that the overall quality of evidence was low to very low, undermining confidence in the findings. The sanitation interventions and contexts in which they were implemented also varied, leading to high heterogeneity across studies, which is probably due to a variety of context specific factors, some of which were assessed (baseline coverage values, length of follow-up etc.) and some which were not assessed (e.g. cultural factors). The pooled estimates had high heterogeneity, however, Caldwell and Welton (2016) have argued that this type of ‘lumping’ approach might still be appropriate for general effectiveness questions. Interventional fidelity was often suboptimal, but due to poor reporting standards in most studies it was not clear whether this was due to poor uptake by participants or poor implementation of the intervention by the implementers. Our study also had a number of strengths. This was the first study, to our knowledge, to assess the impact of various interventions on latrine coverage and latrine use. We performed a rigorous search and study selection that entailed double screening and double extractions. Our search strategy also captured many papers encompassing diverse geographical coverage. We also implemented rigorous risk of bias and quality of evidence assessments in order to understand the strength of our findings.

4.2. Conclusions

Our study contributes to a deeper understanding of how sanitation interventions and sanitation characteristics are associated with coverage and use. Many different intervention types were found to increase coverage of latrines and latrine use. Many different latrine characteristics were also associated with higher latrine use. Our findings could accelerate progress in eliminating open defecation and ultimately improve health.

Competing interests

JVG and MCF have received funding as consultants for the WHO as part of separate assessments of sanitation on health. SB and KOM are employees of WHO. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. The authors declare no other competing interests exist.

Funding

The World Health Organization provided funding for this review. WHO funding was made possible through contributions from the Department for International Development, UK and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Heather Amato, Henrietta Lewis, Divya Naranyan, and Rachel Stelmach for their work on the title, abstract and full text reviews. We also acknowledge Heather Amato’s assistance on data extractions and the risk of bias assessments.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article published under the CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO license which permits users to download and share the article for non-commercial purposes, so long as the article is reproduced in the whole without changes, and provided the original source is properly cited. This article shall not be used or reproduced in association with the promotion of commercial products, services or any entity. There should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organisation, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article’s original URL.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015. United Nations, General Assembly.

- Ahmed M., Begum A., Chowdhury M.A. Social constraints before sanitation improvement in tea gardens of Sylhet, Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010;164:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s10661-009-0890-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B.F., Khush R.S., Ramaswamy P., London A.G., Rajkumar P., Ramaprabha P., Durairaj N., Hubbard A.E., Balakrishnan K., Colford J.M., Jr. Causal inference methods to study nonrandomized, preexisting development interventions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:22605–22610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008944107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard S., Routray P., Majorin F., Peletz R., Boisson S., Sinha A., Clasen T. Impact of Indian Total Sanitation Campaign on latrine coverage and use: a cross-sectional study in Orissa three years following programme implementation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto M.L., Genser B., Strina A., Teixeira M.G., Assis A.M., Rego R.F., Teles C.A., Prado M.S., Matos S.M., Santos D.N., dos Santos L.A., Cairncross S. Effect of city-wide sanitation programme on reduction in rate of childhood diarrhoea in northeast Brazil: assessment by two cohort studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran A., Jenkins M.W., Dabrase P., Bhagwat I. Patterns and determinants of communal latrine usage in urban poverty pockets in Bhopal: India. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2011;16:854–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briceño B., Coville A., Martinez S. Policy Research Working Paper. World Bank; 2015. Promoting handwashing and sanitation: evidence from a large-scale randomized trial in rural Tanzania. 58 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell D.M., Welton N.J. Approaches for synthesising complex mental health interventions in meta-analysis. Evid. Based Ment. Health. 2016;19:16–21. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L., Shah M., Olivia S. The World Bank; 2013. Impact Evaluation of a Large-Scale Rural Sanitation Project in Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso B.A., Dreibelbis R., Ogutu E.A., Rheingans R. If you build it will they come? Factors influencing rural primary pupils’ urination and defecation practices at school in western Kenya. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2014;4:642–653. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso B.A., Freeman M.C., Garn J.V., Dreibelbis R., Saboori S., Muga R., Rheingans R. Assessing the impact of a school-based latrine cleaning and handwashing program on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, Kenya: a cluster-randomized trial. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2014;19:1185–1197. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase C., Ziulu V., Lall P., Kov P., Smets S., Chan V., Lun Y. Addressing the behavioural constraints to latrine uptake: effectiveness of a behaviour-change campaign in rural Cambodia. Waterlines. 2015;34:365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury N., Hossain M.A. BRAC Centre; Dhaka, Bangladesh: 2006. Exploring the Current Status of Sanitary Latrine Use in Shibpur Upazila, Narsingdi District. [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T., Boisson S., Routray P., Torondel B., Bell M., Cumming O., Ensink J., Freeman M., Jenkins M., Odagiri M., Ray S., Sinha A., Suar M., Schmidt W.P. Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2:e645–e653. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey D., Gupta A., Hathi P., Khurana N., Srivastav N., Vyas S., Spears D. Open defecation: evidence from a new survey in rural north India. Econ. Political Wkly. 2014;49:43–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberland P., Edwards T., Hailu G., Harding-Esch E., Andreasen A., Mabey D., Todd J. The impact of community level treatment and preventative interventions on trachoma prevalence in rural Ethiopia. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008;37:549–558. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine J., Sijbesma C. Sustainability of rural sanitation marketing in Vietnam: findings from a new case study. Waterlines. 2011;30:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Drangert J.O., Nawab B. A cultural-spatial analysis of excreting, recirculation of human excreta and health-the case of North West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Health Place. 2011;17:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreibelbis R., Freeman M.C., Greene L.E., Saboori S., Rheingans R. The impact of school water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions on the health of younger siblings of pupils: a cluster-randomized trial in Kenya. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:e91–97. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbers, C., Godfrey, S., Gunning, J.W., van der Velden, M., Vigh, M., 2012. Effectiveness of Large Scale Water and Sanitation Interventions: The One Million Initiative in Mozambique.

- Fenn B., Bulti A.T., Nduna T., Duffield A., Watson F. An evaluation of an operations research project to reduce childhood stunting in a food-insecure area in Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1746–1754. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriman A. BMJ readers choose the sanitary revolution as greatest medical advance since 1840. BMJ. 2007;334:111. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M.C., Clasen T., Brooker S.J., Akoko D.O., Rheingans R. The impact of a school-based hygiene, water quality and sanitation intervention on soil-transmitted helminth reinfection: a cluster-randomized trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013;89:875–883. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M.C., Erhard, L., Fehr, A., Ogden, S., Ahmed, S., Sahin, M., Dooley, 2013. Equity of Access to WASH in Schools: A Comparative Study of Policy and Service Delivery in Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, the Philippines, Timor-Leste, Uganda and Uzbekistan.

- Freeman M.C., Clasen T., Dreibelbis R., Saboori S., Greene L.E., Brumback B., Muga R., Rheingans R. The impact of a school-based water supply and treatment, hygiene, and sanitation programme on pupil diarrhoea: a cluster-randomized trial. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014;142:340–351. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M.C., Garn, J.V., Sclar, G.D., Boisson, S., Medlicott, K., Alexander, K.T., Penakalapati, G., Anderson, D., Grimes, J., Mahtani, A., Rehfuess, E.A., Clasen, T.F., submitted. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garn J.V., Caruso B.A., Drews-Botsch C.D., Kramer M.R., Brumback B.A., Rheingans R.D., Freeman M.C. Factors associated with pupil toilet use in kenyan primary schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2014;11:9694–9711. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110909694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E., Günther, I., 2014. Why don’t households invest in latrines: health, prestige, or safety?

- Guiteras R., Levinsohn J., Mobarak A.M. Sanitation subsidies. Encouraging sanitation investment in the developing world: a cluster-randomized trial. Science. 2015;348:903–906. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J., Norris Falck-Ytter S., Y, Glasziou P., deBeer H., Jaeschke R., Rind D., Meerpohl J., Dahm P., Schünemann H.J. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Montori V., Vist G., Kunz R., Brozek J., Alonso-Coello P., Djulbegovic B., Atkins D., Falck-Ytter Y., Williams J.W., Jr., Meerpohl J., Norris S.L., Akl E.A., Schunemann H.J. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorkos T.W., Maheu-Giroux M., Blouin B., Casapia M. Impact of health education on soil-transmitted helminth infections in schoolchildren of the Peruvian Amazon: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, J., Spears, D., 2013. Village sanitation and children’s human capital: evidence from a randomized experiment by the Maharashtra government.

- Harvey P.A. Zero subsidy strategies for accelerating access to rural water and sanitation services. Water Sci. Technol. J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2011;63:1037–1043. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen M., Routray P., Torondel B., Clasen T. Neighbour-shared versus communal latrines in urban slums: a cross-sectional study in Orissa, India exploring household demographics, accessibility, privacy, use and cleanliness. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;109:690–699. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen M., Routray P., Torondel B., Clasen T. Shared sanitation versus individual household latrines in urban slums: a cross-sectional study in orissa, India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;93:263–268. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huda T.M., Unicomb L., Johnston R.B., Halder A.K., Yushuf Sharker M.A., Luby S.P. Interim evaluation of a large scale sanitation, hygiene and water improvement programme on childhood diarrhea and respiratory disease in rural Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;75:604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, K., Martin, N., Dreibelbis, R., DeBruicker, V., Winch, P., 2015. What factors affect sustained adoption of safe water, hygiene and sanitation technologies? 3ie Systematic Review Summary 2. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), London.

- Jinadu M.K., Adegbenro C.A., Esmai A.O., Ojo A.A., Oyeleye B.A. Health promotion intervention for hygienic disposal of children’s faeces in a rural area of Nigeria. Health Educ. J. 2007;66:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kema K., Semali I., Mkuwa S., Kagonji I., Temu F., Ilako F., Mkuye M. Factors affecting the utilisation of improved ventilated latrines among communities in Mtwara Rural District, Tanzania. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2012;13(Suppl. 1):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J.D., Endeshaw T., Escher E., Alemtaye G., Melaku S., Gelaye W., Worku A., Adugna M., Melak B., Teferi T., Zerihun M., Gesese D., Tadesse Z., Mosher A.W., Odermatt P., Utzinger J., Marti H., Ngondi J., Hopkins D.R., Emerson P.M. Intestinal parasite prevalence in an area of ethiopia after implementing the SAFE strategy, enhanced outreach services, and health extension program. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka S.N., Tetui M., George A., Kisakye A.N., Walugembe D.R., Kiracho E.E. What lessons for sustainability of maternal health interventions can be drawn from rural water and sanitation projects? Perspectives from Eastern Uganda. J. Manage. Sustainability. 2015;5 [Google Scholar]

- Kullman C., Ahmed R., Hanchett S., Khan M.H., Perez E., Devine J., So J., Costain C.J. Long Term Sustainability of Improved Sanitation in Rural Bangladesh. In: Grossman A., editor. Water and Sanitation Program; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- London T., Esper H. Assessing poverty-alleviation outcomes of an enterprise-led approach to sanitation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014;1331:90–105. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby, S.P. 2015. Using behavior change messaging to improve shared toilets in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Malebo, H.M., Makundi, E.A., Mussa, R., Mushi, A.K., A., M.M., Mrisho, M., Senkoro, K.P., Mshana, J.M., Urassa, J., Msimbe, V., Tenu, P., 2012. Outcome and impact monitoring for scaling up Mtumba sanitation and hygiene participatory approach in Tanzania.

- Mathew, K., Zachariah, S., Shordt, K., Snel, M., Cairncross, S., Biran, A., Schmidt, W., 2008. The sustainability and impact of school sanitation, water and hygiene education in Kerala, Southern India, Unpublished report.

- Mathews S., Kumari B. Socio Economic Unit Foundation; Kerala, India: 2004. Sustaining Changes in Hygiene Behaviour: Findings from Kerala Study 2001–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes L.R., Cancio J.A., Cairncross S., Huttly S. Impact of drainage and sewerage on diarrhoea in poor urban areas in Salvador, Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;97:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy G.V., Goswami A., Narayanan S., Amar S. Effect of educational intervention on defaecation habits in an Indian urban slum. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1990;93:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness S.J. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. University of South Florida Scholar Commons, Scholar Commons; 2015. Evaluation of School VIP Latrines and User Preferences and Motivations for Adopting Communal Sanitation Technologies in Zwedru, Liberia. [Google Scholar]

- Ngondi J., Teferi T., Gebre T., Shargie E.B., Zerihun M., Ayele B., Adamu L., King J.D., Cromwell E.A., Emerson P.M. Effect of a community intervention with pit latrines in five districts of Amhara, Ethiopia. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2010;15:592–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna, V., Karanja, B., Thuranira, M., Shordt, K., Snel, M., Cairncross, S., Biran, A., Schmidt, W., 2008. The sustainability and impact of school sanitation, water and hygiene education in Kenya.

- Olsen A., Samuelsen H., Onyango-Ouma W. A study of risk factors for intestinal helminth infections using epidemiological and anthropological approaches. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2001;33:569–584. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001005697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S.R., Arnold B.F., Salvatore A.L., Briceno B., Ganguly S., Colford J.M., Jr., Gertler P.J. The effect of India's total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors and child health in rural Madhya Pradesh: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak S.K., Yang J.C., Dickinson K.L., Poulos C., Patil S.R., Mallick R.K., Blitstein J.L., Praharaj P. Shame or subsidy revisited: social mobilization for sanitation in Orissa, India. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009;87:580–587. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.057422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfadenhauer L.M., Rehfuess E. Towards effective and socio-culturally appropriate sanitation and hygiene interventions in the Philippines: a mixed method approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:1902–1927. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120201902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering A.J., Djebbari H., Lopez C., Coulibaly M., Alzua M.L. Effect of a community-led sanitation intervention on child diarrhoea and child growth in rural Mali: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e701–711. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope, D., Bruce, N., Irving, G., Rehfuess, E., unpublished. Methodological quality of individual studies was assessed using Liverpool Quality Assessment Tools, in: Liverpool, U.o. (Ed.).

- Pradhan M., Rawlings L.B. The impact and targeting of social infrastructure investments: lessons from the Nicaraguan Social Fund. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2002;16:275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk P.M., Muniz M., Nemser B., Somers M.A., McClellan L., Palm C.A., Huynh U.K., Amor Ben, Begashaw Y., McArthur B., Niang J.W., Sachs A., Singh S.E., Teklehaimanot P., Sachs A., Millennium Villages J.D., Study G. The effect of an integrated multisector model for achieving the Millennium Development Goals and improving child survival in rural Sub-Saharan Africa: a non-randomised controlled assessment. Lancet. 2012;379:2179–2188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauniyar G., Orbeta A., Jr, Sugiyarto G. Impact of water supply and sanitation assistance on human welfare in rural Pakistan. J. Dev. Eff. 2011;3:62–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rheinlander T., Samuelsen H., Dalsgaard A., Konradsen F. Hygiene and sanitation among ethnic minorities in Northern Vietnam: does government promotion match community priorities? Soc. Sci. Med. 2010;71:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma E., Buckley C., Jefferson B., Jeffrey P. Assessing users’ experience of shared sanitation facilities: a case study of community ablution blocks in Durban, South Africa. Water SA. 2010;36:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- Routray P., Schmidt W.P., Boisson S., Clasen T., Jenkins M.W. Socio-cultural and behavioural factors constraining latrine adoption in rural coastal Odisha: an exploratory qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:880. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2206-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah S., Negussie A. Community led total sanitation (CLTS): addressing the challenges of scale and sustainability in rural Africa. Desalination. 2009;248:666–672. [Google Scholar]

- Saowakontha S., Pipitgool V., Pariyanonda S., Tesana S., Rojsathaporn K., Intarakhao C. Field trials in the control of Opisthorchis viverrini with an integrated programme in endemic areas of northeast Thailand. Parasitology. 1993;106(Pt. 3):283–288. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin T., Hurlimann E., Silue K.D., Yapi R.B., Houngbedji C., Kouadio B.A., Acka-Douabele C.A., Kouassi D., Ouattara M., Zouzou F., Bonfoh B., N'Goran E.K., Utzinger J., Raso G. Effects of hygiene and defecation behavior on helminths and intestinal protozoa infections in Taabo, Cote d'Ivoire. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclar G.D., Penakalapati G., Amato H.K., Garn J.V., Alexander K., Freeman M.C., Clasen, T., (in press). Assessing the Impact of Sanitation on Indicators of Fecal Exposure Along Principal Transmission Pathways: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2016, DOI:10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sclar, G.D., Penakalapati, G., Garn, J.V., Alexander, K.T., Freeman, M.C., Clasen, T., unpublished. Mixed methods systematic review exploring the relationship between sanitation and education outcomes and personal well being.

- Simms V.M., Makalo P., Bailey R.L., Emerson P.M. Sustainability and acceptability of latrine provision in The Gambia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;99:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thys S., Mwape K.E., Lefevre P., Dorny P., Marcotty T., Phiri A.M., Phiri I.K., Gabriel S. Why latrines are not used: communities' perceptions and practices regarding latrines in a Taenia solium endemic rural area in Eastern Zambia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinies V., Garn J.V., Chang H.H., Freeman M.C. The impact of a school-based water, sanitation, and hygiene program on absenteeism, diarrhea, and respiratory infection: a matched-control trial in Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016;94:1418–1425. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, WHO, 2015. 25 years progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment, WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Wagner E.G., Lanoix J.N. WHO; Geneva: 1958. Excreta Disposal for Rural Areas and Small Communities, Who Monograph Series. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterkeyn J., Cairncross S. Creating demand for sanitation and hygiene through Community Health Clubs: a cost-effective intervention in two districts in Zimbabwe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005;61:1958–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley L., Webster J. The effectiveness and sustainability of two demand driven sanitation and hygiene approaches in Zimbabwe. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2011;1:20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J., Danquah L. Undoing inequity: water, sanitation and hygiene programmes that deliver for all in Uganda and Zambia—an early indication of trends. 38th WEDC International Conference; Loughborough University, UK; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yimam Y.T., Gelaye K.A., Chercos D.H. Latrine utilization and associated factors among people living in rural areas of Denbia district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2013, a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014;18:334. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.334.4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.