Abstract

Steroid receptors are prototypical ligand-dependent transcription factors and a textbook example for allosteric regulation. According to this canonical model, binding of cognate steroid is an absolute requirement for transcriptional activation. Remarkably, the simple one ligand-one receptor model could not be farther from the truth. Steroid receptors, notably the sex steroid receptors, can receive multiple inputs. Activation of steroid receptors by other signals, working through their own signaling pathways, in the absence of the cognate steroids, represents the most extreme form of signaling cross talk. Compared with cognate steroids, ligand-independent activation pathways produce similar but not identical outputs. Here we review the phenomena and discuss what is known about the underlying molecular mechanisms and the biological significance. We hypothesize that steroid receptors may have evolved to be trigger happy. In addition to their cognate steroids, many posttranslational modifications and interactors, modulated by other signals, may be able to tip the balance.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) constitute a large superfamily of transcription factors with 48 members in humans (1). The subfamily of steroid receptors (SR) is represented by the receptors for estrogens [estrogen receptor (ER)-α and ERβ], androgen receptors (AR), glucocorticoid receptors (GR), progestin receptors (PR), and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR). SRs, like most NRs, are composed of three main domains: the N-terminal domain containing the ligand-independent activation function 1 (AF-1), a central DNA binding domain, and a C-terminal hormone binding domain (HBD) containing the ligand-dependent activation function 2 (AF-2) (2, 3). In response to hormones, a host of effectors are engaged in both genomic and nongenomic signaling by SRs to regulate the fate of target cells. In steroid-triggered genomic signaling, ligand binding to the HBD induces a conformational change that promotes the release from the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) complex, translocation into or redistribution within the nucleus, binding to chromatin at specific DNA sequences called hormone response elements, or at other sequences through other transcription factors and recruitment of further transcriptional coregulators to regulate transcription of target genes (4–6). Whereas all SRs can be activated as transcription factors by their cognate steroids, some if not all SRs can also respond to a large variety of other extracellular and intracellular signals in the absence of their cognate ligands (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors Inducing Ligand-Independent Activation of Steroid Receptors

| Factora | Activated SR and Reference(s) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ERb | PRc | AR | |

| Growth factors and growth factor receptors | |||

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | (14, 15) | (16) | (17) |

| Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) | (18) | ||

| Growth arrest-specific 6 (Gas-6) | (19) | ||

| Heregulin (HRG) | (20) | (21) | (19) |

| Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2 = ERBB2) | (20) | (22) | |

| Insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) | (23–25) | (17) | |

| Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) | (17) | ||

| Transforming growth factorα (TGFα) | (15) | ||

| Neurotransmitter | |||

| Dopamine | (26) | (26) | |

| Cytokines and chemokines | |||

| Interleukin-4 | (27) | ||

| Interleukin-6 | (28) | (29, 30) | |

| Interleukin-8 | (31) | ||

| Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1 = CXCL12) | (32) | ||

| Tumor necrosis factorα (TNFα) | (33) | ||

| Peptide hormones and hormone binding proteins | |||

| Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) | (19) | ||

| Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) | (34) | (35) | |

| Leptin | (36) | ||

| Prolactin (PRL) | (37) | ||

| Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) | (38) | ||

| Nutrients and cell-cycle-associated proteins | |||

| Amino acids | (39) | ||

| Cyclin D1 | (40, 41) | ||

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) | (42) | (43) | |

| Transcription factors | |||

| Ets-1 | (44) | ||

| Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif-1α) | (45) | ||

| Kinases | |||

| IKKϵ | (46) | ||

| MAPKK (constitutive mutant) | (47) | ||

| MEKK1 (constitutive mutant) | (48) | ||

| p21-activated kinase1 (PAK1) | (49) | ||

| PI3K | (50) | ||

| Protein kinase A (PKA) | (51) | ||

| Protein kinase B (= Akt) | (52–54) | ||

| Protein kinase C δ type (PKCδ) | (55) | ||

| c-Src | (56) | ||

| TBK1 | (57) | ||

| Others | |||

| Activators of PKA | (23, 58) | (59) | (60) |

| Activators of PKC | (55, 61, 62) | (63) | |

| ATP | (64) | ||

| Ca+2 | (64) | ||

| G protein α subunit (Gα) | (65) | ||

| Inhibitors of phosphatases 1 and 2 A | (26) | (26, 59) | |

| Inhibitors of phosphotyrosine phosphatases | (16) | ||

| Inhibitors of sirtuin 1 | (66) | ||

| Metals, arsenite, and selenite | (67–70) | ||

| Ras (constitutive mutant) | (61) | ||

| Vav3 (a Rho EGF) | (71) | (72) | |

Abbreviations: MEKK1, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1; MAPKK, mitogenactivated protein kinase kinase; IKKϵ, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase subunit ϵ; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; TBK1, IκB kinase-related TANK-binding kinase 1.

This list may be incomplete since the extent of activation varies widely and several reports have indicated that some of these effects may be cell and/or promoter-specific (see for example refs. 22, 73).

Almost all publications have examined ERα. ERβ has only been shown to be activated by EGF (74, 75) and SDF-1 (76), and indirectly by 3,3′-diindolylmethane (77).

The response of PR displays marked species differences: chicken and rodent PRs can be activated in the absence of cognate hormone by a whole series of activators that will only affect human PR in the presence of a ligand, for example the partial antagonist RU486 (78–80); exceptions to the rule are the activation of human PR by heregulin (21) and CDK2 (43). Additional notes: Other steroid receptors, notably GR and MR, are more restricted in their ability to be activated in the absence of ligands. A noteworthy “exception” is the activation of GR by GnRH and TNFα signaling (see refs. 81, 82). Regular updates of this Table are posted at http://www.picard.ch/downloads.

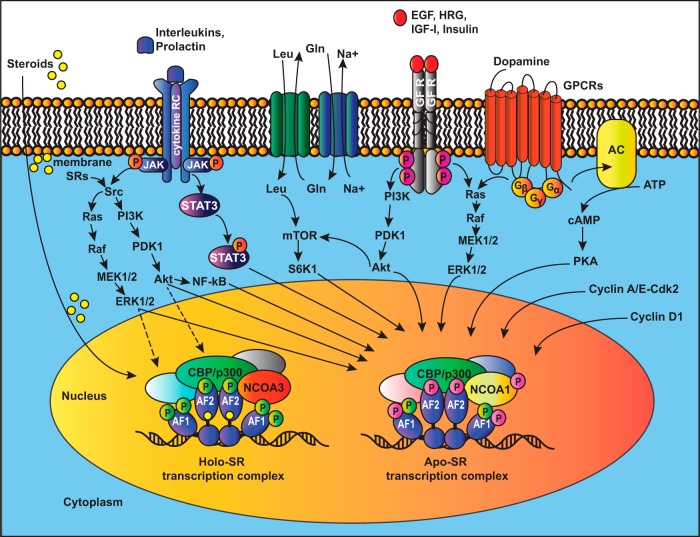

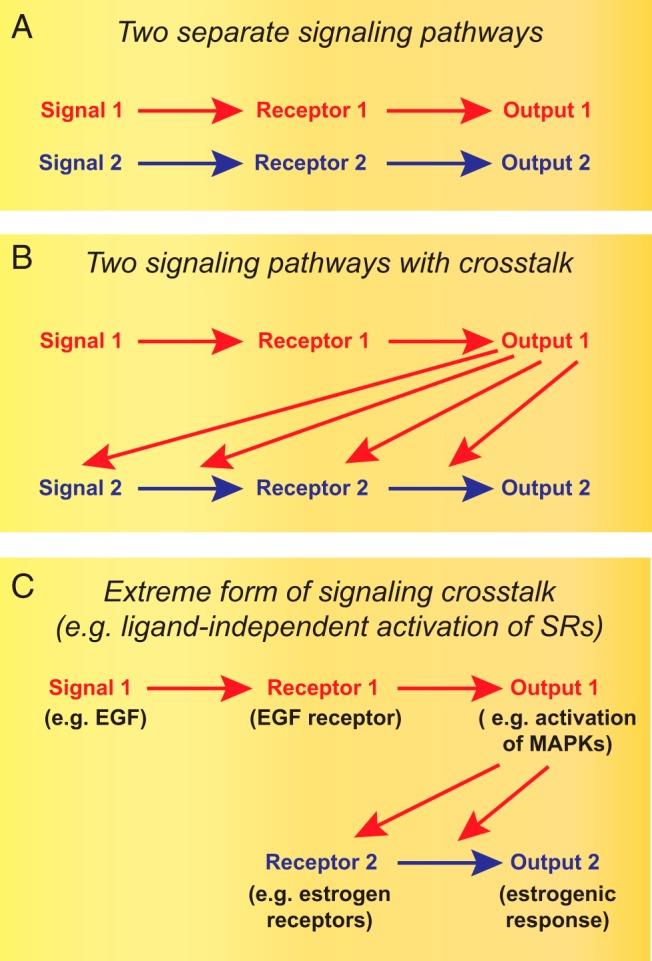

The cross talk of two signal transduction pathways is very common and allows the modulation of one by the other (Figure 1B). For example, the literature is replete with reports on the influence of a plethora of signaling molecules on liganded SRs. In contrast, the ligand-independent activation of SRs is an extreme form of signaling cross talk (Figure 1C). As a consequence of it, the activating signal ends up eliciting an SR response in addition to its canonical signaling output. It is conceivable that ligand-independent pathways also elicit rapid nongenomic signaling by SRs, but because only a little is known about that (7, 8), it will not be further discussed here, except where relevant in the context of a transcriptional output. The focus of this review will be on the ligand-independent mode of transcriptional activation. Whereas other reviews have discussed the ligand-independent activation of individual SRs or the importance of phosphorylation for SR functions (9–13), we will attempt a broader overview, present some alternative activation pathways in detail, explore the complexity of the principal molecular mechanisms, and discuss physiological and pathological implications.

Figure 1. Conceptualization of ligand-independent activation of SRs as an extreme form of signaling cross talk.

From the situation represented schematically in panel A to that in panel C, there is a progressively stronger and stronger impact of signaling pathway 1 (in red) on signaling pathway 2 (in blue).

Discovery of ligand-independent pathways

The first observations of SR activation in the absence of ligand were reported a quarter of a century ago (59). Treatment of tissue culture cells with a cell-permeable derivative of cAMP to activate cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) or okadaic acid, an inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A, triggered the activation of the transiently expressed chicken PR and increased the expression of a reporter gene, which suggested that SR phosphorylation might be essential for SR activation in the absence of ligand. Later studies supported this idea and extended it to the activation of human ERα (26). The binding of dopamine to its membrane-bound receptor, which stimulates adenylate cyclase activity, was demonstrated to induce expression of reporters of ERα and PR activity to the same extent as that induced by their natural ligands. Still in the early 1990s, it was shown that epidermal growth factor (EGF) increased the cell proliferation of the murine female reproductive tract, a well-established estrogenic response (14). Moreover, EGF was found to activate the expression of an estrogen-responsive reporter gene in transfection experiments with the human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line BG-1 in the absence of estrogens (62). These intriguing findings set the stage for the subsequent discoveries of a large variety of related phenomena and, relatively more recently, molecular mechanisms and physiologically and pathologically relevant contexts for these extreme forms of signaling cross talk.

Selected extra- and intracellular factors

EGF

Many years after the initial discovery that EGF can activate ERα in the absence of estrogens (62), EGF was shown to induce the binding of ERα to the promoters of specific genes, which are frequently overexpressed in breast cancers positive for the receptor tyrosine kinase erbB-2 (ERBB2) (83), a member of the EGF receptor family that is often associated with resistance to the ER antagonist tamoxifen (OHT) (84). Even though the cross talk between the EGF signal transduction pathway and ER signaling had been well documented (85, 86), only a little progress had been made toward understanding the molecular mechanisms that make the ERs effectors of the EGF pathway. In this regard, our identification of AF-1 of ERα as the region targeted by EGF had begun to shed light on the mechanism and emphasized the differences with estrogens, which bind the C-terminal HBD and turn on both AF-1 and AF-2 (47).

EGF induces the phosphorylation of specific serine residues, notably serine (S) 118 and S106 of ERα and S106 and S124 of ERβ by MAPK and S167 of ERα by protein kinase B (Akt) (52, 74). S118 was shown to be necessary for activation by EGF, suggesting that its phosphorylation is required. However, a negative charge at that position proved to be insufficient on its own to activate ERα-dependent transcription in the absence of estrogens (47). Because the phosphorylation sites S106 and S124 of ERβ are critical for both to activate and to stimulate the interaction with the steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) (74), these findings indicated for the first time that the ligand-independent activation of SRs may in some cases involve the phosphorylation-stimulated recruitment of specific coactivators. EGF can also activate other SRs, notably PR (16) and AR (17), possibly by using similar molecular mechanisms as for the activation of the ERs. EGF treatment of the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP with EGF promotes the phosphorylation of AR at tyrosine 534 (Y534) by the tyrosine kinase c-Src, and this increases AR nuclear localization and activation, which is accompanied by increased cell proliferation and secretion of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (87, 88). Consistent with this view, dasatinib, an inhibitor of the Src family of tyrosine kinases, can prevent both the phosphorylation of AR at Y534 and transactivation of AR by EGF. The EGF-induced phosphorylation of AR at Y267, through the activation of an unidentified dasatinib-resistant tyrosine kinase, is also associated with AR activation and proliferation of prostate cancer cells in the absence of androgens (19).

Receptor tyrosine kinase erbB-2 (ERBB2)

ERBB2 (also known as HER2) is an important prognostic factor in breast cancer because its overexpression tends to be associated with ER-negative breast cancer, OHT resistance, and overall poor prognosis (89–92). Moreover, it has been shown that the artificial overexpression of ERBB2 in breast cancer cells is sufficient to induce estrogen-independent growth and OHT resistance (20). Another study showed that ERα-positive MCF-7 cells overexpressing ERBB2 (MCF-7/HER2) are even growth stimulated by OHT in vitro and in vivo using xenografts in nude mice (93). Treatment of these cells with estradiol or OHT led to increased phosphorylation and activation of ERα and ERBB2, Akt and MAPK, and the coactivator, amplified in breast cancer 1 protein (AIB1; also known as NCOA3). Upon ERBB2 overexpression, OHT behaves as an agonist inducing the recruitment of an active transcription complex with ERα, AIB1, the CREB-binding protein (CBP), and the histone acetyltransferase EP300 (p300) to ERα target genes (93).

Similarly, the overexpression of ERBB2 in the androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell line LNCaP was shown to promote the activation of unliganded AR, increased secretion of PSA, and ligand-independent growth in vitro and of LNCaP/HER2 xenografts in castrated nude mice (22). The overexpression of ERBB2 in LNCaP cells may induce AR activation by stimulating its interaction with coactivators such as the AR-associated protein 70 (ARA70), an activation that can be blocked with a MAPK inhibitor (94).

Heregulin (HRG)

HRG belongs to a family of growth factors encoded by four different genes. Alternative splicing generates a multitude of isoforms with HRG itself being an isoform of the NRG1 gene (95, 96). The activation of ERBB2 by HRG in breast cancer cells in culture is followed by rapid phosphorylation and activation of the unliganded ERα, increased transcription of ERα target genes, estrogen-independent growth, and OHT resistance (20, 93, 97). Another study found that the treatment of MCF-7 cells with HRG-1β promoted the rapid phosphorylation of Akt, which then phosphorylates and transcriptionally activates ERα. Remarkably, the phosphorylation of Akt is dependent on both ERα and ERBB2 because HRG-1β binds the HER2-HER3 heterodimer, which in turn interacts with membrane-associated ERα to activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and Akt (7). This illustrates the fact that nongenomic signaling by ERα may also be elicited in a ligand-independent fashion and that it may contribute as a part of a feedforward regulatory circuit to activate the transcriptional activity of the unliganded ERα.

AR signaling is also activated by HRG. Treatment of the prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and LAPC-4 with HRG induced the phosphorylation of AR at Y267 and Y363, which is correlated with AR activation, expression of AR-target genes, and androgen-independent growth of prostate tumor cells as xenografts (19, 98). Both sites are phosphorylated by the activated CDC42 kinase 1 (Ack1), itself activated by c-Src. Interestingly, Ack1 becomes part of the AR transactivation complex and is recruited to ensure AR binding to androgen-responsive enhancers on AR-target genes (98). In addition to ERα and AR, HRG activates PR as demonstrated with progestin-responsive mammary tumor cell lines. These respond with increased proliferation, which can be blocked by the use of the progestin antagonist RU486 (21). Activation of a progestin-responsive reporter gene is dependent on the activation of HER3 and the MAPK pathway, mediating the rapid phosphorylation of PR at S294, analogous to what happens in both ligand-dependent and EGF-induced activation of PR (21). Phosphorylation of PR on S294 leads to greater nongenomic c-Src activation. This in turn promotes ERBB2 phosphorylation and activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which is a requirement for HRG-induced mammary tumor growth (99).

Insulin and IGF-1

Insulin and IGF-1 are structurally and biologically related peptide hormones that elicit similar anabolic responses, depending on energy availability and the levels of basic substrates such as amino acids (100–102). They can also promote tumor development by the inhibition of apoptosis and by increasing proliferation (103). Although each of them has its specific receptor, IGF-1 can also bind the insulin receptor, although with lower affinity than insulin, and act as a mediator of enhanced insulin action (104–106). Pioneer studies have demonstrated a signaling cross talk between insulin/IGF-1 and ERα. In primary cultures of immature rat uterine cells, IGF-1 induces increased levels of ERα phosphorylation and the up-regulation of the ERα target gene PGR (23). In neuroblastoma cell lines stably transfected with ERα and cultured in the absence of estrogens, insulin and IGF-1 were found to control growth and morphological differentiation through the activation of ERα-dependent transcription (24). In this system, insulin was found to activate ERα through the AF-2 domain by signaling through Ras (61). A role for ERα in mediating growth factor signaling was also found with a pituitary tumor cell line in that antiestrogens were able to block the growth stimuli of insulin and IGF-1 (25).

Toward elucidating the molecular mechanisms of the activation of ERα by IGF-1, evidence emerged for a role for the activation of Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) upstream of ERα (52, 107). Treatment of MCF-7 cells with IGF-1 resulted in a rapid activation of Akt and increased ERα activity (52) and complemented the effects of active IGF-1 receptor in cell proliferation (108). Moreover, the stable expression of a constitutively active Akt mutant was sufficient to mimic the effects of IGF-1 (52). Serines 104, 106, 118, and 167 of the ERα AF-1 domain were found to be important because their replacements with alanine completely abolished the activation of ERα by Akt (52). Later studies highlighted that Akt phosphorylates ERα on S167 in response to IGF-1 and that this and the induction of cell proliferation are abrogated by the use of the mTOR1 inhibitor rapamycin (107). This is the first study that reported a physical interaction of S6K1 and ERα and a requirement for S6K1 activity for the cross talk of the IGF-1 and ERα pathways (107).

IGF-1 can also activate AR signaling in the absence of androgens, and this is blocked by a pure AR antagonist. In contrast to the situation in breast cancer cells, addition of exogenous IGF-1 does not stimulate the growth of LNCaP cells (17). Thus, the role of IGF-1, if any, in the proliferation of androgen-responsive cells like LNCaP remains to be clarified.

Dopamine

When the neurotransmitter dopamine binds the dopamine receptor, it leads to the production of cAMP by adenylate cyclase. The ensuing activation of the PKA pathway increases the phosphorylation of many target proteins and affects the expression of numerous genes (109, 110). The first hint that dopamine might stimulate SR signaling in vivo came from the observation that a cell-permeable derivative of cAMP (111), inhibition of phosphodiesterases (112), or agonists of D1 type of dopamine receptors (113, 114) can reinforce or even mimic the effects of progesterone in promoting the mating behavior of female rats, which is dependent on PR activity (115). As mentioned before, dopamine was subsequently found to induce the transcriptional activities of human ERα and chicken PR with S628 within the HBD of the latter being crucial (26). Another evidence for the importance of dopamine in the activation of SR signaling in vivo was more recently provided by the discovery that, during development of certain brain areas in female rats, the expression of PR is tightly regulated by dopamine acting through the dopamine D1-like receptor triggering ERα signaling (116).

Cytokines

Cancer cells can secrete proinflammatory cytokines that modulate the tumor microenvironment and may play a role in cancer cell proliferation and survival (117, 118). In addition, several studies have shown that there is signaling cross talk between interleukins (ILs) and SRs. IL-6 was observed to activate the unliganded ERα in transient transfection assays in short-term epithelial cultures established from primary breast tumors (28). The activation of AR by IL-6 in LNCaP cells could be blocked by inhibitors of the PKA and MAPK activities (29). In contrast to other factors that activate the unliganded ERα and AR in these cell lines, IL-6 inhibited the proliferation of LNCaP cells, in agreement with other studies (119, 120), as well as the proliferation of breast cancer cells (121). Considering that the transcriptional activation of SRs by IL-6 requires PKA activity, the apparent discrepancy with the proliferative effects of other factors may be due to the inhibitory effects of PKA on proliferation at least in some instances (122). Another study with LNCaP cells pointed out that STAT3 is required for the activation of AR by IL-6. STAT3 is activated and interacts with AR in response to IL-6 signaling (30). Later the minimal sequence of AR for the interaction with STAT3 was mapped to the N-terminal amino acids 234–559 (123). A role for MAPK in this pathway remains controversial (30, 123). Some contradictions with the afore-mentioned previous studies (29, 119) with regard to the role of PKA and effects on proliferation still remain to be resolved.

Another publication reported that the use of PKA inhibitors did not affect the IL-6-induced AR activity, that PKA activity rather increased MAPK activity when activators of PKA were combined with IL-6, and that IL-6 increased the proliferation of LNCaP cells, even though only modestly (123). Some of these contradictory data could result from differences in methodology due to the use of different PKA inhibitors and different concentrations of IL-6. Additional signaling molecules may be involved in this pathway as suggested by the finding that AR is phosphorylated on Y534 in IL-6-treated LNCaP cells and that this phosphorylation is abolished when c-Src is knocked down (19).

Similarly to IL-6, IL-8 can activate AR signaling in prostate cancer cells. Interestingly, the cross talk between the IL-8 and AR signaling pathways could weaken the apoptotic effects of an AR antagonist in LNCaP cells, suggesting a role of these pathways in the progression of prostate carcinomas to androgen-independent stages and resistance to hormonal therapy (31).

Yet another IL, IL-4 was not only found in the serum of patients with hormone refractory prostate cancers but also proved to be able to activate AR in the absence of androgens (27, 124). This depends on Akt because its inhibition blocks the activation of AR by IL-4 (27). Interestingly, this signaling cross talk somehow intersects with the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway because NF-κB is activated in xenograft tumor models that proliferate in the absence of androgens (125) and because the inhibition of NF-κB by the expression of the NF-κB inhibitor-α (IκBα) reduces the activation of AR by IL-4 (126). Furthermore, to the molecular mechanisms of signaling cross talk, it was later shown that IL-4 induces CBP and p300 expression and enhances their interaction with AR at AR target genes. As a result of the AR and CBP/p300 interaction, AR becomes acetylated, and this in turn increases AR transcriptional activity (127).

Prolactin (PRL)

PRL and estrogens are crucial factors in the normal development of the mammary gland to which they contribute fundamentally for the regulation of cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation (128, 129). However, although the role of estrogens in breast carcinogenesis is well established, the role of PRL and the impact of the signaling cross talk of PRL receptor and ERα are less clear. Studies with breast cancer cell lines have shown that PRL can activate ERα and stimulate proliferation (37, 130). The activation of ERα by PRL is dependent on the phosphorylation of S118 of ERα by the MAPK and PI3K pathways downstream of the activation of c-Src (37). Compelling evidence for a physiological role of the ligand-independent activation of ERα by PRL was recently obtained with a mouse knock-in mutant of ERα. The estrogen-refractory ERα point mutant G525L can still be activated by PRL to stimulate mammary ductal elongation and gene expression at puberty (131). Thus, PRL as a factor contributing to the proliferation of breast tissues might also support the progression of estrogen-independent breast tumors and potentially decrease the efficacy of endocrine therapy.

Amino acids

The levels of free amino acids in blood plasma, apart from their metabolic functions, control a vast number of biological processes including cell cycle progression, reproduction, and immunity (for a review, see references 132 and 133). In addition to reproductive tissues, ERα is also highly expressed in the liver in which it controls glucose homeostasis and gene expression (134, 135). It regulates gene expression in both the presence and the absence of estrogens as seen in immature mice before gonadal production of sex steroids and in ovariectomized adult mice (39, 136). It is in this context that it was discovered that the administration of free amino acids to primary cultures of hepatocytes or to HepG2 hepatoma cells transiently transfected with an estrogen-responsive reporter gene construct caused ERα activation in the absence of estrogens. This effect is dependent on the mTOR pathway and phosphorylation of ERα at S167 and Y534 (39). In vivo, ERα activation by amino acids was correlated with increased blood levels of IGF-1 and with the IGF-1-induced progression of the estrous cycles (39), thus placing ERα in the liver at a pivotal position for integrating food availability and reproduction.

Cyclin D1

Cyclin D1 is one of the most frequently overexpressed cell cycle proteins in breast cancer, either because of gene amplification (137, 138) or response to growth factors (139). Cyclin D1 can bind the hinge domain of ERα and activate ERα in the absence of estrogens independently of its association with a cyclin-dependent kinase partner. Whether this mode of activation of unliganded ERα renders it OHT resistant remains controversial (40, 41). Cyclin D1 appears to activate ERα in the absence of estrogens, including AF-2 mutants, by recruiting coactivators as SRC-1 or the p300/CBP-associated protein through its own C-terminal leucine-rich coactivator binding motif (140, 141). Furthermore, it was recently shown that cyclin D1 also determines estrogen-dependent signaling in vivo in the mammary gland (142), revealing a noncanonical function of cyclin D1 in the assembly of ERα transcription complexes as is the case for unliganded ERα (140, 141). Thus, the overexpression of cyclin D1 might contribute to the enhancement of proliferative effects of active ERα signaling and potentially lower the efficacy of endocrine therapies in breast tumors.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2)

Cyclins E and A and the associated CDK2 are required for cell cycle progression from the G1 to S and S to G2 phases, respectively. The overexpression of cyclin A/CDK2 activates the unliganded ERα, which can be inhibited by the expression of a catalytically inactive CDK2 mutant (42). The cyclin A/CDK2 complex induces the phosphorylation of ERα, notably on S104 and S106 (143). Later studies have shown that the sole overexpression of cylin A or cyclin E, which may pair up with the endogenous CDK2, can activate ERα- and ERα-dependent proliferation of breast cancer cells, rendering them both estrogen independent and resistant to OHT (143, 144). This phenomenology appears to extend to human PR in that the overexpression of cyclin E or of a constitutively active mutant of CDK2 was shown to activate PR in the absence of progestins. CDK2 phosphorylates PR at S400, which is required for PR activation and nuclear localization (43). Because SR signaling itself can promote cell proliferation by increasing the expression of cyclins (144–147), this complicated network of regulatory loops may underlie the stimulation of proliferation and even antihormone resistance.

Molecular mechanisms

Most pathways promoting the ligand-independent activation of SRs are initiated by extracellular or intracellular signals that activate kinases, which may phosphorylate the SRs themselves and/or their coregulators (Figure 2). Growth factors like EGF and HRG or the overexpression of the receptor ERBB2 activate SRs mainly through the Akt and MAPK pathways, which phosphorylate preferentially the AF-1 regions of ERα and ERβ (7, 47, 52, 74, 93) or through c-Src to activate, for example, AR signaling (19, 87, 88). Similarly, PRL activates the ERα through the MAPK and PI3K pathways as a result of c-Src activation (37). IGF-1 was shown to activate ERα signaling by a mechanism that involves the activation of mTOR by Akt and the subsequent phosphorylation and activation of the AF-1 region of ERα by the downstream kinase S6K1 (107). Circulating amino acids, which are essential activators of the mTOR pathway, activate ERα signaling in the liver and increase serum levels of IGF-1 (39). In turn, IGF-1 triggers ERα activation in the absence of estrogens, notably in nonreproductive tissues such as the liver (136). The key question is what happens downstream of the phosphorylation of this or that residue in a particular SR. To the best of our knowledge, there is as yet no clear case in which the recruitment of a coactivator has been demonstrated to be specifically induced by the phosphorylation of a particular SR residue and required for ligand-independent activation by a growth factor. Phosphorylation may directly contribute to generating the protein interaction surface or induce a conformational change that allows protein binding (148). One protein, whose direct binding depends on the phosphorylation of the ERα AF-1 domain, is the stromelysin-1 platelet-derived growth factor-responsive element-binding protein (SPBP); however, functionally it proved to be a repressor rather than an activator that could mediate growth factor signaling (149).

Figure 2. A multitude of signaling pathways can activate unliganded steroid receptors.

Many intra- and extracellular signals lead to the activation of kinases (or other transcription factors) that modulate SR and coregulator activities, thereby promoting the assembly of an alternative apo-SR transcription complex at target genes. For comparison, a more canonical SR transcription complex assembled in response to the cognate steroid is shown on the left (holo-SR transcription complex). For simplicity, the only additional signaling inputs that are indicated for this liganded complex are the ones from nongenomic steroid signaling through membrane-associated SRs (with broken arrows). The cognate steroid is symbolized as a yellow ball. Holo-SR and apo-SR are liganded and unliganded SRs, respectively. The complexity of phosphorylation sites is indicated by different colors.

The molecular mechanisms that allow cAMP/PKA to turn on SR transcriptional activity remain only partially understood. The fact that PKA does indeed directly phosphorylate ERα (23, 150, 151) led to the suggestion that this may be what activates ERα transcriptionally (23). Phosphorylation of S305, located at the boundary of the ERα HBD, was proposed to mediate the ligand-independent activation of ERα by PKA and p21-activated kinase1 (49, 51, 152, 153). Although it definitely enables OHT to act as an agonist promoting ERα dimerization and the recruitment of the coactivator SRC-1 (51, 57, 152, 154), we could not confirm that the phosphorylation of S305 is required for activation of ERα by cAMP (58). Instead, we demonstrated that the coactivator-associated arginine methytransferase 1 (CARM1) is the critical target of PKA. Upon phosphorylation, CARM1 directly binds ERα and contributes to its activation (58). CARM1 binding, by itself not being sufficient, activation of ERα by cAMP must involve the phosphorylation of other proteins by PKA. This may include other coactivators such as the glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) that are recruited to ERα transactivation complexes in response to cAMP, even though no PKA-induced phosphorylation was seen in this particular case (155). The molecular chaperone Hsp90, also a PKA substrate (156), is another potential candidate. The activation of unliganded ERα may depend on its release (157), and, intriguingly, the ligand-independent activation of ERα by the overexpression of the protein arginine methytransferase 6 (PRMT6) correlates with the dissociation of Hsp90 (158).

Cyclins can activate SRs in the absence of steroids in CDK-dependent and independent manners. As mentioned above, the CDK-dependent ones may modulate unliganded SR activities primarily by direct phosphorylation (42, 43, 143), whereas cyclin D1 may function as a bridging factor to recruit coactivators (40, 140).

Yet a slightly different paradigm may be exemplified by cytokines. Although they do turn on kinases that may again act by phosphorylating both the SRs and coregulators, the activation of other transcription factors such as STAT3 and NF-κB may be particularly relevant to these pathways. Because the PI3K/Akt pathway can activate NF-κB (159, 160), it seems plausible that a cytokine such as IL-4 could activate AR signaling by the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway. However, this remains merely as a speculation because NF-κB can on its own bind regulatory elements of the prototypical AR target gene PSA, independently of AR activity (125). It would be necessary to dissect the existence of a PI3K/Akt/NF-κB/AR axis with the use of a pure AR antagonist, knockdowns of NF-κB, and a genome-wide analysis of this signaling cross talk.

What happens downstream of both phosphorylation and interaction with other proteins? There is mounting evidence that the ligand-independent pathways, compared with cognate steroids, stimulate both the assembly of alternative transcription complexes (Figure 2) and the selection of slightly different ensembles of genome-wide chromatin binding sites (cistromes). The interplay between transcription complexes and cistromes adds obviously another layer of complexity. As alluded to above, we found that CARM1 directly binds to ERα in response to cAMP signaling (58), whereas it is indirectly recruited to the estrogen-activated ERα through GRIP1 (161, 162). Differences between ERα complexes induced by estrogen vs IGF-1 have also been reported for specific target sites (163). Both EGF and cAMP have been found to determine the ERα cistromes slightly differently from estrogen (83, 164). To what extent this is affected by pioneer factors such as Forkhead box protein A1 (FoxA1) or partner transcription factors such as AP1 and NF-κB or the differences in assembling transcription complexes needs further investigations. Hence, the nature of the signal affects both the target selection and the specifics of the complex that is assembled. Beyond that, it may also affect the kinetics of the transcriptional response (86).

As a consequence of these differences, it is not surprising that the transcriptional outputs of SRs are distinctly shaped by the activating signal. Gene expression profiles controlled by ERα can substantially differ, depending on whether ERα is activated by estrogen, cAMP, EGF, or one of these in combination with OHT (83, 164, 165).

Biological implications

Whereas the steroid-induced functions of SRs have been in the limelight for many decades, the potential physiological functions of the ligand-independent activation of SRs have not received enough attention yet, and the picture remains very fragmentary (summarized in Table 2). To a large extent, it is their pathologically perverted functions that have been the focus of speculations. Nevertheless, the use of pharmacological and genetic tools is beginning to pay off.

Table 2.

Physiological Functions of Ligand-Independent Activation of Steroid Receptors

| Functions | Tissues | Factors | Receptors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive behavior | Brain | Dopamine, EGF | ERα, PR | (113–115, 166) |

| Social behavior | Brain | Dopamine | ERα | (116, 167) |

| Mammary gland development | Breast | PRL | ERα | (131) |

| Gene expression, glucose homeostasis, estrous cycle | Liver | Amino acids, IGF-1 | ERα | (39, 134–136) |

| Uterine growth | Uterus | EGF, IGF-1 | ERα | (170–173) |

| Epididymal sperm concentration | Epididymis | Growth factors | ERα | (174) |

Dopamine and EGF induce the reproductive behavior of female rodents. Experiments with antagonists and antisense RNAs injected into ventromedial nucleus support the notion that these responses are mediated by the ligand-independent activation of PR and ERα (113–115, 166). Dopamine also regulates the social behavior of neonatal rats by activating the unliganded ERα in specific brain areas (116, 167). Although these nice biological cases seem unambiguous, one cannot completely exclude that liganded ERα and/or PR are required for the initial set-up of the responses. The experimental dissection of these complex systems remains a challenge for the future.

In the breast, PRL can activate ERα signaling in the absence of estrogens and show synergistic effects with estrogens, which suggests a cooperative role of PRL and estrogens during the extension of the primary ductal tree of the mammary gland at puberty (131). In addition, it may represent a mechanism of estrogen-independent proliferation of certain breast tumors because PRL is also synthesized locally in the epithelium (168, 169).

The activation of unliganded ERα by circulating IGF-1 in nonreproductive tissues such as the liver (136) may be the counterpart of the activation by estrogens in reproductive tissues. As mentioned above, free amino acids affect IGF-1 levels through unliganded ERα (39), but what the significance of the response of ERα to IGF-1 is still needs to be carefully worked out for nonreproductive tissues. A stronger case can be made for reproductive tissues such as the uterus. Both EGF and IGF-1 stimulate uterine growth through ERα (170, 171). An estrogen-insensitive knock-in mutant of ERα in the mouse with the amino acid change G525L still mediates the uterotrophic effects of IGF-1, even in ovariectomized females (172). Although uterine growth may be stimulated by the ligand-independent activities of ERα in tissues other than the epithelium (173), these genetic experiments argue very strongly that this is a case of ligand-independent functions of ERα. Likewise, in males, this ERα mutant still contributes to regulating fertility in response to growth factors that promote the concentration of epididymal sperm (174).

Throughout this article, we have already pointed out the large and steadily growing body of literature on the existence of this type of signaling cross talk in cancer cell lines. This evidence strongly supports the notion that these pathways are important in cancer, both for progression and resistance to endocrine therapy. To provide more formal proof, these concepts will have to be tested with animal models.

Concluding remarks

Where did all this come from and could one learn from other NRs? This relates to the question of what came first in the evolution of NRs in general and of SRs in particular: ligand-dependent or ligand-independent activation. In modern day NRs, both activation modes can be found, but whether the ancestral NR was constitutively active or a ligand-binding factor, for example a nutrient sensor, is still a matter of debate (175, 176). The evolution of SRs can be traced back more clearly to an ancestral estrogen-sensitive SR (177, 178). Loss of ligand binding and constitutive activity of ER in invertebrates and diversification in vertebrates appear to have been secondary events (175, 178–180). One can only speculate that the huge diversity of types of signaling cross talk and underlying molecular mechanisms that seem at play, both in the presence and the absence of ligand, are the result of a subsequent evolutionary diversification. Even though there may be some common principles such as posttranslational modifications affecting ligand, DNA, or coregulator binding, already exemplified in NRs other than SRs (181–184), each NR remains a unique case.

Considering the huge variety of signals that can trigger the transcriptional activation of unliganded SRs (apo-SRs), it is almost a miracle that they can be off and function as ligand-dependent transcription factors in any context at all. To be able to respond efficiently to their cognate steroids, SRs may have evolved to be inherently unstable, poised to be turned on. The slightest perturbation may push the equilibrium toward the active form. Whereas cognate steroids and other direct ligands are particularly good at this, other factors influencing SR functions might be able to pull the trigger. These factors could include the posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylations of the SRs themselves, an increase in the levels or activities of coregulators, and changes in the local chromatin environment at target genes. Conversely, other factors might tend to shift the equilibrium toward the off state. To what extent the molecular chaperone Hsp90 complex plays this role is still not entirely clear and may depend on the particular SR (157).

Many other members of the NR superfamily display constitutive or ligand-reversed activities (2, 3). Perhaps SRs, or at least some SRs such as the ERα, are not fundamentally different. It came as a big surprise when it was found that the unliganded ERα cycles at a target gene, albeit with a slightly different periodicity and amplitude than the estrogen-activated ERα (185). It was speculated that this transcriptionally nonproductive cycling might be essential to prepare a target gene for a rapid and robust response to estrogen. A recent analysis of the cistrome of the unliganded ERα substantially broadened this picture. The apo-ERα was found to be present at a large number of chromatin sites, mostly a substantial subset of the estrogen-induced ones, and to regulate a specific gene expression program (186). Interestingly, for one particular gene, apo-ERα had previously been identified as a coactivator (187), again seemingly contradicting the canonical model of SRs only being activated upon binding cognate steroid. At this point, there is too much evidence to shrug off these “basal” activities as being due to experimental artifacts caused by contaminating steroids. Whether these basal activities are induced or affected by ligand-independent pathways discussed here is unknown, but it is tempting to hypothesize that they are the manifestations of SRs living on the edge.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the helpful comments of Dr Marta Madon-Simon and Lilia Bernasconi in the revision of the manuscript as well as Dr Kinsey Maundrell for sharing his opinions during the preparation of our work.

This work was supported by the Canton de Genève, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the Fondation Medic.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Canton de Genève, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the Fondation Medic.

Footnotes

- Ack1

- activated CDC42 kinase 1

- AF-1

- activation function 1

- AF-2

- activation function 2

- AR

- androgen receptor

- CARM1

- coactivator-associated arginine methytransferase 1

- CBP

- CREB-binding protein

- CDK2

- cyclin-dependent kinase 2

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ERBB2

- receptor tyrosine kinase erbB-2

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- HBD

- hormone binding domain

- HRG

- heregulin

- Hsp90

- heat shock protein 90

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- OHT

- tamoxifen

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PR

- progestin receptor

- PRL

- prolactin

- PSA

- prostate-specific antigen

- S

- serine

- S6K1

- S6 kinase 1

- SR

- steroid receptor

- SRC-1

- steroid receptor coactivator 1

- STAT3

- signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

References

- 1. Robinson-Rechavi M, Carpentier AS, Duffraisse M, Laudet V. How many nuclear hormone receptors are there in the human genome? Trends Genet. 2001;17:554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamamoto KR. Steroid receptor regulated transcription of specific genes and gene networks. Annu Rev Genet. 1985;19:209–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beato M, Truss M, Chávez S. Control of transcription by steroid hormones. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;784:93–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors, RXR, and the big bang. Cell. 2014;157:255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stoica GE, Franke TF, Wellstein A, et al. Heregulin-β1 regulates the estrogen receptor-α gene expression and activity via the ErbB2/PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24:1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferriere F, Habauzit D, Pakdel F, Saligaut C, Flouriot G. Unliganded estrogen receptor α promotes PC12 survival during serum starvation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanchez M, Picard N, Sauve K, Tremblay A. Challenging estrogen receptor β with phosphorylation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maggi A. Liganded and unliganded activation of estrogen receptor and hormone replacement therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1054–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamont KR, Tindall DJ. Alternative activation pathways for the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anbalagan M, Huderson B, Murphy L, Rowan BG. Post-translational modifications of nuclear receptors and human disease. Nucl Recept Signal. 2012;10:e001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trevino LS, Weigel NL. Phosphorylation: a fundamental regulator of steroid receptor action. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24:515–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Nelson KG, Bidwell MC, et al. Coupling of dual signaling pathways: epidermal growth factor action involves the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4658–4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Teng CT, Ross KA, Parker MG, Korach KS, McLachlan JA. Peptide growth factors elicit estrogen receptor-dependent transcriptional activation of an estrogen-responsive element. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:992–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Bai W, Allgood VE, Weigel NL. Multiple signaling pathways activate the chicken progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Culig Z, Hobisch A, Cronauer MV, et al. Androgen receptor activation in prostatic tumor cell lines by insulin-like growth factor-I, keratinocyte growth factor, and epidermal growth factor. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5474–5478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piotrowicz RS, Ding L, Maher P, Levin EG. Inhibition of cell migration by 24-kDa fibroblast growth factor-2 is dependent upon the estrogen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3963–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu Y, Karaca M, Zhang Z, Gioeli D, Earp HS, Whang YE. Dasatinib inhibits site-specific tyrosine phosphorylation of androgen receptor by Ack1 and Src kinases. Oncogene. 2010;29:3208–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pietras RJ, Arboleda J, Reese DM, et al. HER-2 tyrosine kinase pathway targets estrogen receptor and promotes hormone-independent growth in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1995;10:2435–2446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Labriola L, Salatino M, Proietti CJ, et al. Heregulin induces transcriptional activation of the progesterone receptor by a mechanism that requires functional ErbB-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1095–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat Med. 1999;5:280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aronica SM, Katzenellenbogen BS. Stimulation of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription and alteration in the phosphorylation state of the rat uterine estrogen receptor by estrogen, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, and insulin-like growth factor-I. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma ZQ, Santagati S, Patrone C, Pollio G, Vegeto E, Maggi A. Insulin-like growth factors activate estrogen receptor to control the growth and differentiation of the human neuroblastoma cell line SK-ER3. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:910–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newton CJ, Buric R, Trapp T, Brockmeier S, Pagotto U, Stalla GK. The unliganded estrogen receptor (ER) transduces growth factor signals. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;48:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Power RF, Mani SK, Codina J, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Dopaminergic and ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. Science. 1991;254:1636–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee SO, Lou W, Hou M, Onate SA, Gao AC. Interleukin-4 enhances prostate-specific antigen expression by activation of the androgen receptor and Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2003;22:7981–7988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Speirs V, Kerin MJ, Walton DS, Newton CJ, Desai SB, Atkin SL. Direct activation of oestrogen receptor-α by interleukin-6 in primary cultures of breast cancer epithelial cells. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1312–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hobisch A, Eder IE, Putz T, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates prostate-specific protein expression in prostate carcinoma cells by activation of the androgen receptor. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4640–4645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen T, Wang LH, Farrar WL. Interleukin 6 activates androgen receptor-mediated gene expression through a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-dependent pathway in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2132–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seaton A, Scullin P, Maxwell PJ, et al. Interleukin-8 signaling promotes androgen-independent proliferation of prostate cancer cells via induction of androgen receptor expression and activation. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kasina S, Macoska JA. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis promotes ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351:249–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gori I, Pellegrini C, Staedler D, Russell R, Jan C, Canny GO. Tumor necrosis factor-α activates estrogen signaling pathways in endometrial epithelial cells via estrogen receptor α. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;345:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Demay F, De Monti M, Tiffoche C, Vaillant C, Thieulant ML. Steroid-independent activation of ER by GnRH in gonadotrope pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3340–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Turgeon JL, Waring DW. Activation of the progesterone receptor by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone self-priming signaling pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:860–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Catalano S, Mauro L, Marsico S, et al. Leptin induces, via ERK1/ERK2 signal, functional activation of estrogen receptor α in MCF-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19908–19915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gonzalez L, Zambrano A, Lazaro-Trueba I, et al. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by prolactin in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:1298–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakhla AM, Romas NA, Rosner W. Estradiol activates the prostate androgen receptor and prostate-specific antigen secretion through the intermediacy of sex hormone-binding globulin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6838–6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Della Torre S, Rando G, Meda C, et al. Amino acid-dependent activation of liver estrogen receptor α integrates metabolic and reproductive functions via IGF-1. Cell Metab. 2011;13:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zwijsen RM, Wientjens E, Klompmaker R, van der Sman J, Bernards R, Michalides RJ. CDK-independent activation of estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Cell. 1997;88:405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neuman E, Ladha MH, Lin N, et al. Cyclin D1 stimulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity independent of cdk4. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5338–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trowbridge JM, Rogatsky I, Garabedian MJ. Regulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional enhancement by the cyclin A/Cdk2 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10132–10137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pierson-Mullany LK, Lange CA. Phosphorylation of progesterone receptor serine 400 mediates ligand-independent transcriptional activity in response to activation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10542–10557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tolon RM, Castillo AI, Jimenez-Lara AM, Aranda A. Association with Ets-1 causes ligand- and AF2-independent activation of nuclear receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8793–8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cho J, Bahn JJ, Park M, Ahn W, Lee YJ. Hypoxic activation of unoccupied estrogen-receptor-α is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;100:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guo JP, Shu SK, Esposito NN, Coppola D, Koomen JM, Cheng JQ. IKKϵ phosphorylation of estrogen receptor α Ser-167 and contribution to tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3676–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47. Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ, Picard D. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2174–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abreu-Martin MT, Chari A, Palladino AA, Craft NA, Sawyers CL. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 activates androgen receptor-dependent transcription and apoptosis in prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5143–5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang RA, Mazumdar A, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. P21-activated kinase-1 phosphorylates and transactivates estrogen receptor-α and promotes hyperplasia in mammary epithelium. EMBO J. 2002;21:5437–5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Campbell RA, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Patel NM, Constantinidou D, Ali S, Nakshatri H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-mediated activation of estrogen receptor α: a new model for anti-estrogen resistance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9817–9824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Michalides R, Griekspoor A, Balkenende A, et al. Tamoxifen resistance by a conformational arrest of the estrogen receptor α after PKA activation in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martin MB, Franke TF, Stoica GE, et al. A role for Akt in mediating the estrogenic functions of epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4503–4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun M, Paciga JE, Feldman RI, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT2, activated in breast cancer, regulates and is induced by estrogen receptor α (ERα) via interaction between ERα and PI3K. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5985–5991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ma Y, Hu C, Riegel AT, Fan S, Rosen EM. Growth factor signaling pathways modulate BRCA1 repression of estrogen receptor-α activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1905–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. De Servi B, Hermani A, Medunjanin S, Mayer D. Impact of PKCδ on estrogen receptor localization and activity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4946–4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Feng W, Webb P, Nguyen P, et al. Potentiation of estrogen receptor activation function 1 (AF-1) by Src/JNK through a serine 118-independent pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wei C, Cao Y, Yang X, et al. Elevated expression of TANK-binding kinase 1 enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E601–E610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Carascossa S, Dudek P, Cenni B, Briand PA, Picard D. CARM1 mediates the ligand-independent and tamoxifen-resistant activation of the estrogen receptor α by cAMP. Genes Dev. 2010;24:708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Denner LA, Weigel NL, Maxwell BL, Schrader WT, O'Malley BW. Regulation of progesterone receptor-mediated transcription by phosphorylation. Science. 1990;250:1740–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nazareth LV, Weigel NL. Activation of the human androgen receptor through a protein kinase A signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19900–19907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Patrone C, Ma ZQ, Pollio G, Agrati P, Parker MG, Maggi A. Cross-coupling between insulin and estrogen receptor in human neuroblastoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Pimentel M, Teng CT, Korach KS, McLachlan JA. Cross talk between peptide growth factor and estrogen receptor signaling systems. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(suppl 7):35–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Darne C, Veyssiere G, Jean C. Phorbol ester causes ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Divekar SD, Storchan GB, Sperle K, et al. The role of calcium in the activation of estrogen receptor-α. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1658–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bratton MR, Antoon JW, Duong BN, et al. Gαo potentiates estrogen receptor α activity via the ERK signaling pathway. J Endocrinol. 2012;214:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moore RL, Faller DV. SIRT1 represses estrogen-signaling, ligand-independent ERα-mediated transcription, and cell proliferation in estrogen-responsive breast cells. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Martin MB, Reiter R, Pham T, et al. Estrogen-like activity of metals in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2425–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stoica A, Pentecost E, Martin MB. Effects of selenite on estrogen receptor-α expression and activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2000;79:282–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stoica A, Katzenellenbogen BS, Martin MB. Activation of estrogen receptor-α by the heavy metal cadmium. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stoica A, Pentecost E, Martin MB. Effects of arsenite on estrogen receptor-α expression and activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3595–3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee K, Liu Y, Mo JQ, Zhang J, Dong Z, Lu S. Vav3 oncogene activates estrogen receptor and its overexpression may be involved in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lyons LS, Rao S, Balkan W, Faysal J, Maiorino CA, Burnstein KL. Ligand-independent activation of androgen receptors by Rho GTPase signaling in prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gehm BD, McAndrews JM, Jordan VC, Jameson JL. EGF activates highly selective estrogen-responsive reporter plasmids by an ER-independent pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;159:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F, Giguere V. Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor β through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Mol Cell. 1999;3:513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tremblay A, Giguere V. Contribution of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and CREB binding protein in ligand-independent activity of estrogen receptor β. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;77:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sauve K, Lepage J, Sanchez M, Heveker N, Tremblay A. Positive feedback activation of estrogen receptors by the CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5793–5800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vivar OI, Saunier EF, Leitman DC, Firestone GL, Bjeldanes LF. Selective activation of estrogen receptor-β target genes by 3,3′-diindolylmethane. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1662–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Beck CA, Weigel NL, Moyer ML, Nordeen SK, Edwards DP. The progesterone antagonist RU486 acquires agonist activity upon stimulation of cAMP signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4441–4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sartorius CA, Groshong SD, Miller LA, et al. New T47D breast cancer cell lines for the independent study of progesterone B- and A-receptors: only antiprogestin-occupied B-receptors are switched to transcriptional agonists by cAMP. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3868–3877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sartorius CA, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB. Antagonist-occupied human progesterone receptors bound to DNA are functionally switched to transcriptional agonists by cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9262–9266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kotitschke A, Sadie-Van Gijsen H, Avenant C, Fernandes S, Hapgood JP. Genomic and nongenomic cross talk between the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor and glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1726–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Verhoog NJ, Du Toit A, Avenant C, Hapgood JP. Glucocorticoid-independent repression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α-stimulated interleukin (IL)-6 expression by the glucocorticoid receptor: a potential mechanism for protection against an excessive inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19297–19310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lupien M, Meyer CA, Bailey ST, et al. Growth factor stimulation induces a distinct ER(α) cistrome underlying breast cancer endocrine resistance. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2219–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Benz CC, Scott GK, Sarup JC, et al. Estrogen-dependent, tamoxifen-resistant tumorigenic growth of MCF-7 cells transfected with HER2/neu. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;24:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Picard D. Molecular mechanisms of cross-talk between growth factors and nuclear receptor signaling. Pure Appl Chem. 2003;75:1743–1756. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Berno V, Amazit L, Hinojos C, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor-α by E2 or EGF induces temporally distinct patterns of large-scale chromatin modification and mRNA transcription. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Guo Z, Dai B, Jiang T, et al. Regulation of androgen receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kraus S, Gioeli D, Vomastek T, Gordon V, Weber MJ. Receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) and Src regulate the tyrosine phosphorylation and function of the androgen receptor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11047–11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Borg A, Baldetorp B, Ferno M, et al. ERBB2 amplification is associated with tamoxifen resistance in steroid-receptor positive breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 1994;81:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tsutsui S, Ohno S, Murakami S, Hachitanda Y, Oda S. Prognostic value of c-erbB2 expression in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;79:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Pancholi S, Lykkesfeldt AE, Hilmi C, et al. ERBB2 influences the subcellular localization of the estrogen receptor in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells leading to the activation of AKT and RPS6KA2. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:985–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, et al. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Yeh S, Lin HK, Kang HY, Thin TH, Lin MF, Chang C. From HER2/Neu signal cascade to androgen receptor and its coactivators: a novel pathway by induction of androgen target genes through MAP kinase in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5458–5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Holmes WE, Sliwkowski MX, Akita RW, et al. Identification of heregulin, a specific activator of p185erbB2. Science. 1992;256:1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Falls DL, Rosen KM, Corfas G, Lane WS, Fischbach GD. ARIA, a protein that stimulates acetylcholine receptor synthesis, is a member of the neu ligand family. Cell. 1993;72:801–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Loi S, Sotiriou C, Haibe-Kains B, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies activated growth factor signaling in poor prognosis (Luminal-B) estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mahajan NP, Liu Y, Majumder S, et al. Activated Cdc42-associated kinase Ack1 promotes prostate cancer progression via androgen receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8438–8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Proietti CJ, Rosemblit C, Beguelin W, et al. Activation of Stat3 by heregulin/ErbB-2 through the co-option of progesterone receptor signaling drives breast cancer growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1249–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rinderknecht E, Humbel RE. The amino acid sequence of human insulin-like growth factor I and its structural homology with proinsulin. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:2769–2776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Straus DS, Takemoto CD. Effect of fasting on insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-1) and growth hormone receptor mRNA levels and IGF-1 gene transcription in rat liver. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kaaks R, Lukanova A. Energy balance and cancer: the role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60:91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Moses AC, Young SC, Morrow LA, O'Brien M, Clemmons DR. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I increases insulin sensitivity and improves glycemic control in type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1996;45:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Cheng CM, Reinhardt RR, Lee WH, Joncas G, Patel SC, Bondy CA. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates developing brain glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10236–10241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Gauguin L, Klaproth B, Sajid W, et al. Structural basis for the lower affinity of the insulin-like growth factors for the insulin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2604–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Becker MA, Ibrahim YH, Cui X, Lee AV, Yee D. The IGF pathway regulates ERα through a S6K1-dependent mechanism in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:516–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Gaben AM, Sabbah M, Redeuilh G, Bedin M, Mester J. Ligand-free estrogen receptor activity complements IGF1R to induce the proliferation of the MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Snyder GL, Fienberg AA, Huganir RL, Greengard P. A dopamine/D1 receptor/protein kinase A/dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein (Mr 32 kDa)/protein phosphatase-1 pathway regulates dephosphorylation of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10297–10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Gomes AR, Cunha P, Nuriya M, et al. Metabotropic glutamate and dopamine receptors co-regulate AMPA receptor activity through PKA in cultured chick retinal neurones: effect on GluR4 phosphorylation and surface expression. J Neurochem. 2004;90:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Beyer C, Canchola E, Larsson K. Facilitation of lordosis behavior in the ovariectomized estrogen primed rat by dibutyryl cAMP. Physiol Behav. 1981;26:249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Beyer C, Canchola E. Facilitation of progesterone induced lordosis behavior by phosphodiesterase inhibitors in estrogen primed rats. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:731–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mani SK, Allen JM, Clark JH, Blaustein JD, O'Malley BW. Convergent pathways for steroid hormone- and neurotransmitter-induced rat sexual behavior. Science. 1994;265:1246–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Apostolakis EM, Garai J, Fox C, et al. Dopaminergic regulation of progesterone receptors: brain D5 dopamine receptors mediate induction of lordosis by D1-like agonists in rats. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4823–4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mani SK, Allen JM, Lydon JP, et al. Dopamine requires the unoccupied progesterone receptor to induce sexual behavior in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1728–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Olesen KM, Auger AP. Dopaminergic activation of estrogen receptors induces fos expression within restricted regions of the neonatal female rat brain. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Lee YS, Choi I, Ning Y, et al. Interleukin-8 and its receptor CXCR2 in the tumour microenvironment promote colon cancer growth, progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1833–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sullivan NJ, Sasser AK, Axel AE, et al. Interleukin-6 induces an epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:2940–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Degeorges A, Tatoud R, Fauvel-Lafeve F, et al. Stromal cells from human benign prostate hyperplasia produce a growth-inhibitory factor for LNCaP prostate cancer cells, identified as interleukin-6. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ritchie CK, Andrews LR, Thomas KG, Tindall DJ, Fitzpatrick LA. The effects of growth factors associated with osteoblasts on prostate carcinoma proliferation and chemotaxis: implications for the development of metastatic disease. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1145–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Douglas AM, Goss GA, Sutherland RL, et al. Expression and function of members of the cytokine receptor superfamily on breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Stork PJ, Schmitt JM. Cross talk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Ueda T, Bruchovsky N, Sadar MD. Activation of the androgen receptor N-terminal domain by interleukin-6 via MAPK and STAT3 signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7076–7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Wise GJ, Marella VK, Talluri G, Shirazian D. Cytokine variations in patients with hormone treated prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;164:722–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Chen CD, Sawyers CL. NF-κB activates prostate-specific antigen expression and is upregulated in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2862–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Lee SO, Lou W, Nadiminty N, Lin X, Gao AC. Requirement for NF-(κ)B in interleukin-4-induced androgen receptor activation in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2005;64:160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Lee SO, Chun JY, Nadiminty N, Lou W, Feng S, Gao AC. Interleukin-4 activates androgen receptor through CBP/p300. Prostate. 2009;69:126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 128. Shyamala G, Chou YC, Louie SG, Guzman RC, Smith GH, Nandi S. Cellular expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in mammary glands: regulation by hormones, development and aging. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Brisken C, O'Malley B. Hormone action in the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Gutzman JH, Miller KK, Schuler LA. Endogenous human prolactin and not exogenous human prolactin induces estrogen receptor α and prolactin receptor expression and increases estrogen responsiveness in breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. O'Leary KA, Jallow F, Rugowski DE, et al. Prolactin activates ERα in the absence of ligand in female mammary development and carcinogenesis in vivo. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4483–4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Wu G. Functional amino acids in growth, reproduction, and health. Adv Nutr. 2010;1:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Wu G, Bazer FW, Davis TA, et al. Arginine metabolism and nutrition in growth, health and disease. Amino Acids. 2009;37:153–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Takeda K, Toda K, Saibara T, et al. Progressive development of insulin resistance phenotype in male mice with complete aromatase (CYP19) deficiency. J Endocrinol. 2003;176:237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Venken K, Schuit F, Van Lommel L, et al. Growth without growth hormone receptor: estradiol is a major growth hormone-independent regulator of hepatic IGF-1 synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2138–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Ciana P, Raviscioni M, Mussi P, et al. In vivo imaging of transcriptionally active estrogen receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Gillett C, Fantl V, Smith R, et al. Amplification and overexpression of cyclin D1 in breast cancer detected by immunohistochemical staining. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1812–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Ormandy CJ, Musgrove EA, Hui R, Daly RJ, Sutherland RL. Cyclin D1, EMS1 and 11q13 amplification in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;78:323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Musgrove EA, Hamilton JA, Lee CS, Sweeney KJ, Watts CK, Sutherland RL. Growth factor, steroid, and steroid antagonist regulation of cyclin gene expression associated with changes in T-47D human breast cancer cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3577–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Zwijsen RM, Buckle RS, Hijmans EM, Loomans CJ, Bernards R. Ligand-independent recruitment of steroid receptor coactivators to estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3488–3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. McMahon C, Suthiphongchai T, DiRenzo J, Ewen ME. P/CAF associates with cyclin D1 and potentiates its activation of the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5382–5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Casimiro MC, Wang C, Li Z, et al. Cyclin D1 determines estrogen signaling in the mammary gland in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Rogatsky I, Trowbridge JM, Garabedian MJ. Potentiation of human estrogen receptor α transcriptional activation through phosphorylation of serines 104 and 106 by the cyclin A-CDK2 complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22296–22302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Bindels EM, Lallemand F, Balkenende A, Verwoerd D, Michalides R. Involvement of G1/S cyclins in estrogen-independent proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:8158–8165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Sutherland RL, Lee CS, Feldman RS, Musgrove EA. Regulation of breast cancer cell cycle progression by growth factors, steroids and steroid antagonists. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Doisneau-Sixou SF, Sergio CM, Carroll JS, Hui R, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Estrogen and antiestrogen regulation of cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Sabbah M, Courilleau D, Mester J, Redeuilh G. Estrogen induction of the cyclin D1 promoter: involvement of a cAMP response-like element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11217–11222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Gburcik V, Picard D. The cell-specific activity of the estrogen receptor α may be fine-tuned by phosphorylation-induced structural gymnastics. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]