Abstract

Kisspeptin and the G protein-coupled receptor 54 (GPR54) are highly abundant in the pancreas. In addition, circulating kisspeptin directly influences insulin secretion through GPR54. However, the mechanisms by which kisspeptin affects insulin release are unclear. The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor, Isl-1, is expressed in all pancreatic islet cells and is involved in regulating both islet development and insulin secretion. We therefore investigated potential interactions between kisspeptin and Isl-1. Our results demonstrate that Isl-1 and GPR54 are coexpressed in mouse pancreatic islet β-cells and NIT cells. Both in vitro and in vivo results demonstrate that kisspeptin-54 (KISS-54) inhibits Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion and both the in vivo and in vitro effects of KISS-54 on insulin gene expression and secretion are abolished when an Isl-1-inducible knockout model is used. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the direct action of KISS-54 on insulin secretion is mediated by Isl-1. Our results further show that KISS-54 influences Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion through the protein kinase C-ERK1/2 pathway. Conversely, insulin has a feedback loop via the Janus kinase-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway regulating kisspeptin expression and secretion. These findings are important in understanding mechanisms of insulin secretion and metabolism in diabetes.

Abnormalities in insulin secretion are closely associated with diabetes (1), an obesity-related disease that is increasing worldwide. Therefore, mechanisms regulating insulin secretion under physiological and pathological conditions have been extensively studied (2). Insulin secretion and global insulin levels are affected by a number of factors, including extrinsic factors acting on β-cells, such as leptin (3, 4), and kisspeptin (5–10) and β-cell-intrinsic factors such as paired box transcription factor 4 (Pax4) (11), Nkx6.1 (12), V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A (MafA) (13), Forkhead-a (14), pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 (Pdx1) (15, 16), and Isl-1 (17, 18), most of which are required for pancreatic development and maintenance of cellular function (19–21). Interactions between extrinsic and intrinsic factors and the molecular mechanisms modulating insulin secretion still remain to be elucidated.

The KISS-1 gene encodes a hydrophobic 145-amino acid protein that can be hydrolyzed to produce kisspeptin (KISS)-54, kisspeptin-14, kisspeptin-13, and kisspeptin-10, which form a family of peptides called kisspeptins (22). KISS-1 was originally discovered in breast cancer and in melanoma cell lines, and KISS-1 expression may suppress the metastatic potential of malignant melanoma cells (23). G protein-coupled receptor 54 (GPR54), a G-protein-coupled receptor, has been identified as the receptor for kisspeptins (22, 23). There is evidence that the hypothalamic KISS-1/GPR54 system is involved in controlling puberty onset by regulating the release of GnRH from hypothalamic neurons (24–26). Recent studies have shown that kisspeptin and GPR54 are highly expressed in pancreatic islet β-cells (9) and are involved in regulating insulin secretion (5–10).

The signaling pathways of kisspeptins have been investigated in different tissues. It is generally thought that kisspeptin's binding to GPR54 stimulates the G protein Gq to activate phospholipase C, which increases intracellular inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate, Ca2+ mobilization, and arachidonic acid release and enhances the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK (22), similar to the pathway found in hypothalamic GnRH neurons (27). However, in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, the enhancing effect of GPR54 on ERK1/2 activity is mediated by the G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 and β-arrestin-2 (28). In mouse embryonic fibroblast cell lines, β-arrestin-1 inhibits the regulating effect of KISS1/GPR54 on ERK1/2 expression (29). In the pancreatic islet, phospholipase C, ERK1/2, and intracellular Ca2+ concentration [(Ca2+)(i)] take part in the intracellular signaling pathways of kisspeptin-10 (5), but key factors and molecular mechanisms by which kisspeptins influence insulin secretion require further elucidation.

The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Isl-1 is required for pancreatic development (19) and insulin secretion (30–32). Isl-1 regulates hormone biosynthesis and secretion in pancreatic islet cells by interactions with transcription factors Maf (13, 33), BETA2 (18), cAMP response binding protein (31), and Arx (32). Genetic studies on morbidly obese humans suggest that Isl-1 is closely associated with type 2 diabetes (34). However, factors affecting Isl-1 expression and its relationship to insulin secretion under physiological and pathological condition require further investigation.

The aims of the present study are to investigate whether Isl-1 mediates the effects of kisspeptin on insulin secretion and to identify interactions between kisspeptin signaling molecules and the transcription factor Isl-1. We found that kisspeptin inhibits Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion and that Isl-1 ablation significantly weakens effects of kisspeptin on insulin secretion. In addition, our findings demonstrate that Isl-1 acts downstream of kisspeptin signaling through the protein kinase C (PKC)-ERK1/2 pathway to influence insulin secretion, and that insulin has a feedback loop through the Janus kinase (JAK)-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway that regulates kisspeptin's gene expression and secretion. These results are important in understanding mechanisms regulating insulin secretion and for finding novel targets for physiological or pharmacological interventions for diseases resulting from insulin secretion abnormalities, such as diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Animal treatments and reagents

Adult male mice (6–8 wk) used for this study were approved by the Chinese Association for Laboratory Animal Sciences. The mice were kept in a 14-hour light, 10-hour dark cycle, with food and water provided ad libitum. The animals were killed by cervical dislocation.

Mice glucose and insulin tolerance tests were performed as previously described (35–37), and blood glucose was measured using an Ascensia Elite glucometer (Bayer).

The collected pancreatic tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 6 hours at room temperature (RT), embedded in paraffin, and cut to 5-μm sections. The pancreatic tissue for mRNA and protein analysis were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and preserved at −80°C.

Human KISS-54 (27–54) peptide was supplied by RayBiotech (RayBiotech). We used a floxed Isl-1 allele (Isl-1F/F) in which loxP sites were inserted into the introns flanking exon4 of the Isl-1 locus and a tamoxifen inducible knock-in-Isl-1 mER-Cre-mER allele (38, 39). Isl-1MCM/+ mice were interbred with Isl-1F/F mice to produce Isl-1MCM/F induced knockout mice (Isl-1MCM/Del). In Isl-1MCM/F and Isl-1F/+ mice, the mice pancreas were harvested after 5 consecutive days of injecting them with 1 mg per 10 g weight of tamoxifen as previously reported (38). Isl-1F/+ mice were used as controls.

Cell culture

NIT cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL) and antibiotics in an H2O-saturated 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The preparation of isolated pancreatic islets was performed as previously described (40). The islets from Isl-1MCM/F and Isl-1F/+ were both treated with 5 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; Sigma) for 48 hours.

Radioimmunoassay

NIT cells and the pancreatic islets from inducible knockout (IKO) and control mice were incubated in DMEM containing 16.5 mM glucose and subjected to various concentrations of KISS-54 (0.1, 1, and 10 nM) for 3 hours. Each incubation vial contained 100 islets. Immediately after incubation, an aliquot of the medium was removed and frozen for subsequent insulin assays with RIA reagents provided by the Beijing North Institute Biological Technology (Beijing, China). For each RIA, the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 10% and less than 15%, respectively.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

NIT cells were incubated in DMEM containing 16.5 mM glucose and subjected to 10−8 M insulin for 12 hours. For in vivo mouse studies, insulin was administered ip to the mice at a dose of 5 IU/kg for 12 hours. The harvested medium, serum, and pancreatic tissues were frozen for subsequent assays of kisspeptin with the ELISA kit reagents (Uscn Life Science).

Islet size

Islet size was determined using Image-Pro Plus imaging software (Media Cybernetics) following the manufacturer's instructions as previously described (41). Briefly, pancreatic tissues from four control mice and four IKO mice were used. Pancreatic tissue were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 6 hours at RT and embedded in paraffin. To determine the average islet size in pancreas, consecutive sections of 5-μm thickness were cut, five sections were collected at 200 μm intervals from each mouse according to the previous report (42), and all large islets (>15 × 103 μm2) in each section were selected and analyzed. The tissue slices were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in ethanol, and then pancreas sections were stained with hematoxylin. The sections were photographed, and areas of all selected islets and the number of these islets were determined by using Image-Pro Plus(Media Cybernetics). Finally, the average islet size was calculated by total islets area divided by number of islets.

Ca2+ measurement

The [Ca2+](i) of NIT cells was measured using a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-4500; Hitachi) as described in our previous report (43).

PCR and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TriZol reagent kit (Vigorous Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RT-PCR was performed using 2 μg of total RNA reverse transcribed using a Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Isl-1, GPR54, insulin, and the internal control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene expression were assayed using the primers in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers' Name and Sequence

| Experiment | Primers' | Name and Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR | ||

| GAPDH | Sense | GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA |

| Antisense | GGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTA | |

| Isl-1 | Sense | CGGCACAGAGCGGAAGAAACCA |

| Antisense | AAACCAACGCAGCTCCGCCTT | |

| Insulin | Sense | AGGACCCACAAGTGGAACAACT |

| Antisense | CAACGCCAAGGTCTGAAGGT | |

| MafA | Sense | TTCAGCAAGGAGGAGGTCAT |

| Antisense | CCGCCAACTTCTCGTATTTC | |

| Pdx1 | Sense | CGTCGCATGAAGTGGAAA |

| Antisense | CGAGGTCACCGCACAATCT | |

| Pax4 | Sense | CTCCAGTTCTTCCCAGTCC |

| Antisense | TAGTCCGATTCCTGTGGC | |

| Nkx6.1 | Sense | GGAGAGTCAGGTCAAGGTC |

| Antisense | CCTTGAGCCTCTCGGTCT | |

| Ngn3 | Sense | GCTTCGCCCACAACTACA |

| Antisense | TAGATAGAGCCCCAGTCCC | |

| Common PCR | ||

| GAPDH | Sense | AAGCCCATCACCATCTTCCAG |

| Antisense | AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT | |

| Isl-1 | Sense | AGTCATCCGAGTGTGGTTTC |

| Antisense | CATGCTGTTGGGTGTATCTG | |

| GPR54 | Sense | GGCTCCGTCCAACGCTTCAG |

| Antisense | TGTGCTTGTGGCGGCAGATA | |

| Plasmid construction | ||

| Insulin | Sense | CTGCTGCCTGAGTTCTGCTT |

| Antisense | GGGTTGGGAGTTACTGGGTC |

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, the pancreas sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and treated with 10% normal goat or donkey serum in PBS to block nonspecific binding sites. For insulin, GPR54, and kisspeptin staining, we used the following antibodies: mouse antiinsulin (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit-anti-GPR54 (1:50; Abcam), rabbit-antikisspeptin (1:150; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals). The sections were then incubated with a biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG (1:200; Zymed Laboratories) or a biotinylated goat antimouse IgG (1:200; Zymed Laboratories) for 2 hours at RT. The sections for Isl-1 were treated with 10% normal donkey serum in PBS to block nonspecific binding sites and then incubated with goat anti Isl-1 antibody (1:50; R&D Systems) overnight at 4°C and incubated with a biotinylated donkey antigoat IgG (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich) at RT for 2 hours. Fluorescein isothiocyanate or tetraethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (1:50; Southern Biotech) were used for immunofluorescence and were incubated at RT for 2 hours. Finally, the sections were counterstained with the DNA dye Hoechst33258 and/or 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole.

For immunocytochemistry, the NIT cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, the NIT cells were stained using the same protocol as above.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as in our previous report (43). For Isl-1 analysis, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-Isl-1 antibody (1:1000; R&D Systems) and mouse anti-GAPDH antibody (1:8000; mouse monoclonal). For ERK, JAK, Akt, and MafA analysis, the membranes were blocked as above and then incubated in 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2, p-JAK, p-AKt, total ERK1/2, total JAK, and total AKt antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology, the MafA antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. After washing in 0.1% Tween 20-Tris-buffered saline, the membranes were incubated with the respective alkaline phosphatase-coupled antibodies (1:5000; Zymed Laboratories) for 2 hours at RT. The immunoreactive proteins were visualized using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma-Aldrich).

Plasmid DNA constructs

The 410-bp region of the insulin gene promoter from −1262 to −1143 bp was amplified from rat genomic DNA by PCR using specific primers (Table 1). The fragment was inserted into the pGL3.0 luciferase reporter vector (Promega). The expression vector for murine Isl-1 pXJ40-Myc-Isl-1 vector was kindly provided by Dr Xinmin Cao (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore).

Luciferase reporter assay

The Isl-1 expression vector (Addgene) was cotransfected with insulin luciferase reporter vector and pTK-Ranilla vector (Promega) into 293T cells and NIT cells. The cells were harvested 24 hours after transfection. Luciferase activity was measured using the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega) and on a Modulus microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems). The values shown by Firefly (Fluc) to Renilla luciferase (Rluc) activity ratio were normalized to that of an empty luciferase reporter control.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using one-way factorial ANOVA, followed by a Student's t test. All values were expressed as means ± SD of three independent experiments. A value of P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Isl-1 and GPR54 are expressed in mouse pancreas and NIT cells

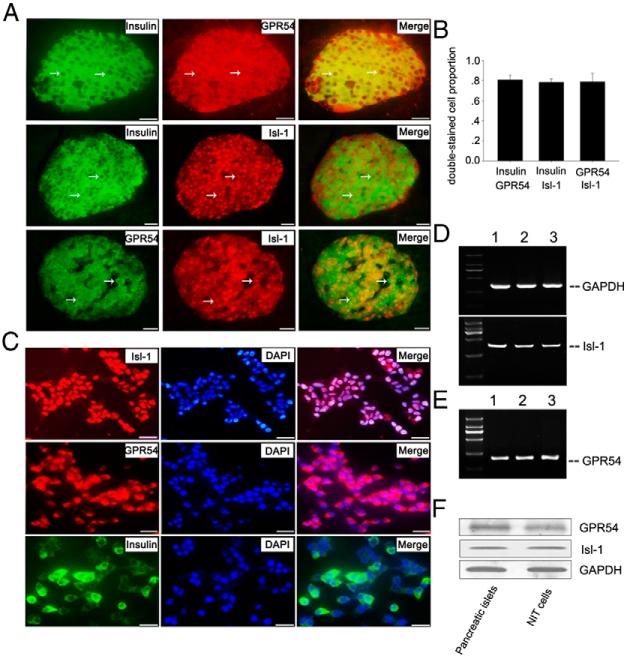

To study whether Isl-1 is involved in mediating effects of KISS-54 on insulin secretion, we initially examined expression of Isl-1 and KISS-54 receptor (GPR54) in mouse pancreas and NIT cells by RT-PCR and immunofluorescence. Double-immunofluorescence staining show that nearly all insulin immunopositive cells express GPR54 and Isl-1 in mouse pancreas (Figure 1, A and B). PCR (Figure 1, D and E) and Western blot (Figure 1F) results show that both Isl-1 and GPR54 are detected in mouse pancreatic islets. These data show that GPR54, Isl-1 and insulin are coexpressed in all pancreatic islet β-cells but not in surrounding pancreatic exocrine glands.

Figure 1.

Expression of Isl-1, GPR54, and insulin in NIT cells and in mouse pancreatic islet. A, Double-immunofluorescence staining of insulin and GPR54, insulin and Isl-1, and Isl-1 and GPR54 in the mouse pancreas. White arrows represent double-stained cells. B, Percentages of double-stained cells accounting for total pancreatic islet cells in the mouse pancreas. C, Immunofluorescence results with antibodies to Isl-1, insulin, and GPR54 in NIT cells. D, Gene expression of GPR54 in NIT cells (lane 1), mouse pancreatic islet (lane 2), and mouse hypothalamus (lane 3) by PCR. E, Gene expression of GAPDH and Isl-1 in NIT cells (lane 1), mouse pancreatic islet (lane 2), and mouse embryonic heart (lane 3) by PCR. The heart and hypothalamus are positive for Isl-1 and GPR54 expression. F, Western blot analysis of Isl-1 and GPR54 protein levels in NIT cells and pancreatic islets. Bars, 30 μm.

Consistent with the results in the pancreas, Isl-1 and GPR54 are also expressed at significant levels in all NIT cells (Figure 1, C–F). In addition, most NIT cells contain insulin (Figure 1C), in agreement with a previous report (44). These results suggest that NIT cells could be used as an in vitro cell model to investigate potential molecular cross talk between KISS-54 and Isl-1 for insulin secretion regulation.

KISS-54 suppresses Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion in NIT cells

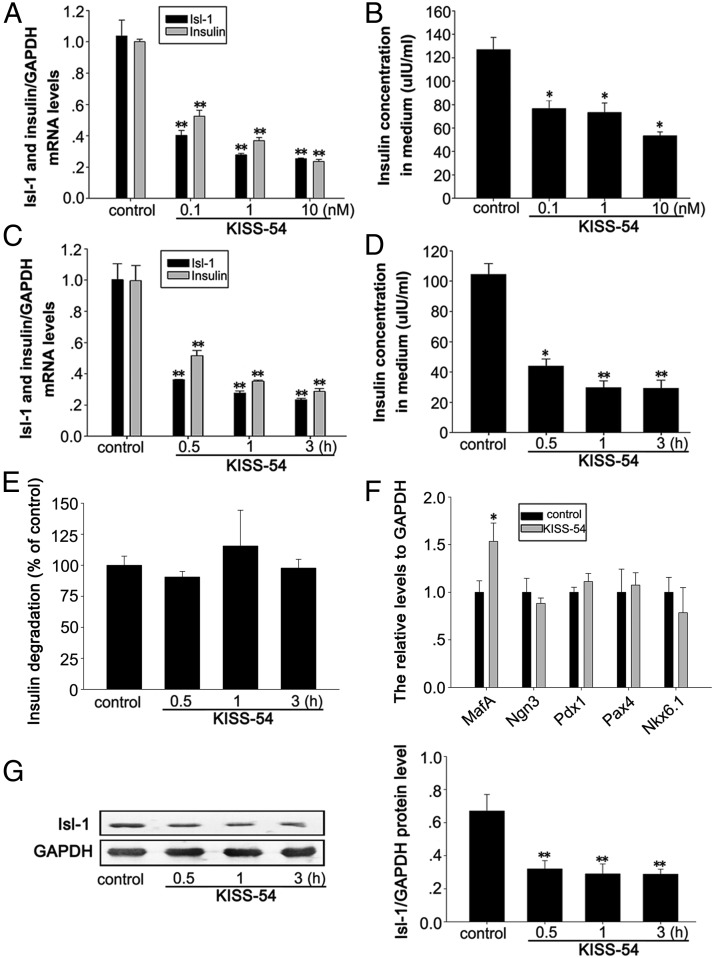

To investigate a potential functional relationship between KISS-54 and Isl-1 in regulating insulin synthesis and secretion, we assessed the effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion in NIT cells, which were incubated in DMEM with 16.5 mM glucose. Cultured NIT cells were treated with 0.1, 1, or 10 nM KISS-54 for 3 hours according to the previous reports (6, 45–48), and cellular Isl-1 and insulin mRNA levels as well as insulin levels in the culture medium were analyzed. Results demonstrate that KISS-54 treatment causes a sharp decrease in Isl-1 and insulin gene expression (Figure 2A, P < .01) and reduced insulin secretion (Figure 2B, P < .05).

Figure 2.

Effects of KISS-54 treatment on the expression of Isl-1 and insulin and insulin secretion in cultured NIT cells. A, Relative mRNA levels of Isl-1 and insulin were detected by RT-PCR in NIT cells treated with different doses of KISS-54. B, Insulin levels detected by RIA in NIT cells treated with different doses of KISS-54. C, Relative mRNA levels of Isl-1 and insulin measured by RT-PCR after treatment with 10 nM KISS-54 for specific treatment durations. D, Insulin levels detected by RIA in NIT cells treated with 10 nM KISS-54 for specific treatment durations. E, The effect of KISS-54 on insulin degradation with 10 nM KISS-54 for diifferent treatment durations. F, Relative mRNA levels of MafA, Pdx1, Pax4, Nkx6.1, and Ngn3 measured by RT-PCR in NIT cells after treatment with 10 nM KISS-54 for 3 hours. G, Isl-1 protein levels detected by Western blot analysis of NIT cells treated with 10 nM KISS-54 for specific treatment durations. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < .05 and **, P < .01.

To check whether the effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion are dependent on the duration of KISS-54 treatment, we measured insulin secretion and gene expression of Isl-1 and insulin after incubating NIT cells with 10 nM KISS-54 for 0.5, 1, or 3 hours. Results demonstrate that 0.5, 1, and 3 hours of treatment with KISS-54 significantly decreases Isl-1 and insulin gene expression (Figure 2C, P < .01), but there is no obvious time dependence of the effects of KISS-54 treatment. Similar effects on Isl-1 protein levels were detected by Western blot, and the effects on insulin secretion were detected by RIA (Figure 2, D and G, P < .01).

To investigate whether KISS-54 has a role in regulating insulin degradation, we tested the effect of KISS-54 treatment on insulin degradation according to the previous reports (49–51), and the results showed that KISS-54 treatment has no obvious effect on insulin degradation in different time points (Figure 2E).

In addition, we analyzed the effects of KISS-54 on the mRNA expression of islet transcription factors MafA, Pdx1, Pax4, Nkx6.1, and neurogenin 3 (Ngn3) in NIT cells after 3 hours of treatment with 10 nM KISS-54. Results demonstrate that KISS-54 treatment has no significant effect on mRNA levels of these factors, with the exception of MafA mRNA levels, which significantly increased (Figure 2F, P < .05).

KISS-54 suppresses Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion in the pancreas

To determine whether KISS-54 has similar physiological effects on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion in vivo, we administered 10 nM of KISS-54 in 200 μL 0.9% NaCl to mice via a caudal vein injection. Pancreatic Isl-1 mRNA and protein levels were examined at 0.5, 3, and 6 hours, respectively. Results show that KISS-54 significantly decreases pancreatic Isl-1 and insulin mRNA levels at 0.5 hours, compared with the control, which persisted until 6 hours (Figure 3A, P < .01). However, pancreatic Isl-1 protein levels and serum insulin levels significantly decline at 3 hours and persist until 6 hours (Figure 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

Effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion in the pancreas. A, Relative mRNA levels of Isl-1 and insulin by RT-PCR in mouse pancreas after injection with 10 nM KISS-54 via caudal vein injection at 0 hours (control), NaCl (no leptin), 0.5, 3, and 6 hours. B, Isl-1 protein levels in the mouse pancreas injected with 10 nM KISS-54 harvested at distinct time points after injection and detected by Western blot (GAPDH was used as a loading control). C, Insulin levels in the mouse pancreas injected with 10 nM KISS-54 and harvested at distinct time points after injection as measured by RIA. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < .05 and **, P < .01.

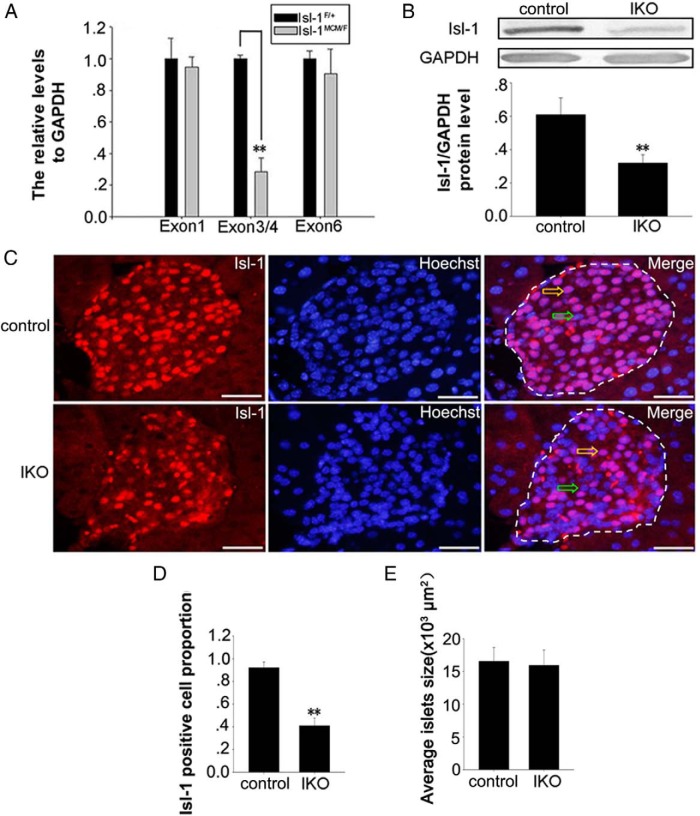

Isl-1 is efficiently knocked down in the Isl-1-inducible knockout mice

To confirm whether the effects of KISS-54 on insulin secretion are Isl-1 dependent, we used Isl-1MCM/F IKO mice. Isl-1F/+ mice were used as controls. The strategy used for Isl-1 deletion is similar to previous reports (38, 39). We first compared Isl-1 gene expression between IKO mice (Isl-1MCM/F) and control mice (Isl-1F/+). The results show that the inducible ablation of Isl-1 results in a 71.4% decrease in mRNA levels of exons 3/4 in the pancreas of IKO mice compared with the controls (Figure 4A, P < .01). Similar to the changes in Isl-1 gene expression, Isl-1 protein levels in pancreatic islets of IKO mice are significantly lower than those in controls as seen by the Western blot (Figure 4B). Immunofluorescence results (Figure 4, C and D) demonstrate that the percentage of Isl-1 positive cells is significantly lower in the pancreas of IKO mice than in the controls. These findings are similar to our recent report (52). In addition, there are no evident size differences between the number of islets per pancreas between the control and IKO mice (Figure 4E). These data demonstrate the efficient Cre mediated deletion of Isl-1 in vivo.

Figure 4.

Isl-1 ablation efficiency in IKO mouse pancreas. A, RT-PCR primers targeting exon 1, exon 3/4, and exon 6 were used to assay Isl-1 mRNA in IKO and control mice. B, Western blot of Isl-1 protein in IKO and control mice. C, Immunofluorescence (yellow/green arrows represent positive/negative cells) staining in IKO and control mice. Red fluorescence shows Isl-1, and blue fluorescence represents counterstained nuclei. D, The percentage of Isl-1 positive cells in pancreatic islets of IKO and control mice. E, Islet size was determined using Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics) in IKO and control mice. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significant differences are indicated by **, P < .01. Bars, 30 μm.

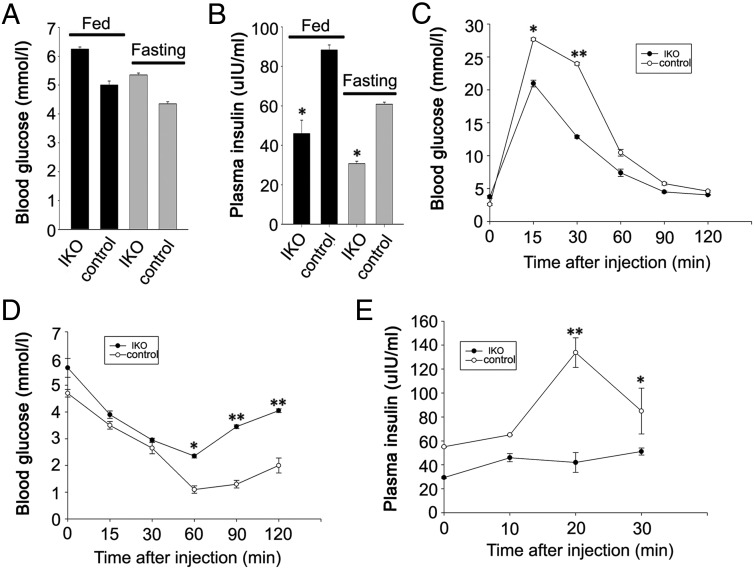

Effects of Isl-1 deletion on glucose and insulin tolerance tests

To evaluate effects of Isl-1 deletion on the general metabolisms of the mouse, we compared blood glucose and plasma insulin levels between IKO and control mice in fasting and fed conditions. Results show that Isl-1 IKO mice display higher blood glucose levels (Figure 5A) and lower plasma insulin levels as compared with control mice in both fasting and regularly fed conditions (Figure 5B, P < .05).

Figure 5.

Glucose homoeostasis in Isl-1 IKO and control mice. A, Blood glucose levels in IKO and control mice. B, Plasma insulin levels in IKO and control mice. C, Blood glucose levels before and after ip injection of glucose in IKO and control mice. D, Blood glucose levels before and after ip injection of insulin in IKO and control mice. E, Plasma insulin levels before and after ip injection of glucose in IKO and control mice at specific time points after injection. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 (n = 6).

In addition, we evaluated islet function by ip glucose and insulin tolerance tests. Isl-1 IKO mice display profound glucose and insulin tolerance impairment (Figure 5, C and D, P < .01). In vivo glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was markedly depressed in Isl-1 IKO mice compared with control mice (Figure 5E, P < .01), potentially explaining their impaired glucose tolerance.

Effects of KISS-54 on insulin gene expression and secretion in IKO mice and isolated islets of IKO mice

Because a numbers of factors, including MafA, Pdx1, Pax4, Nkx6.1, and Ngn3, are involved in regulation of insulin gene expression and islet function, we examined the effects of the Isl-1 deletion expression of these genes. Real-time PCR results show that Isl-1 deletion significantly decreases MafA mRNA and protein levels but does not significantly change the gene expression of the other transcription factors (Figure 6, A and B, P < .05).

Figure 6.

Effects of KISS-54 on insulin gene expression and secretion in IKO mice and isolated islets. A, Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA levels of islet transcription factors in IKO and control mice. B, Western blot of MafA and GAPDH protein levels in IKO and control mice. C, Insulin mRNA levels measured by real-time PCR in mice treated with 10 nM KISS-54 via caudal vein injection at 0 hours (control), NaCl (no KISS-54), and 6 hours. D, Serum insulin levels measured by RIA in mice treated with 10 nM KISS-54 via caudal vein injection. E, Preparation of isolated pancreatic islets was performed by retrograde injection of a collagenase solution via the bile-pancreatic duct. F, RT-PCR primers targeting exon 1, exon 3/4, and exon 6 were used to assay Isl-1 mRNA in isolated pancreatic islets from IKO and control mice. G, RIA detected insulin levels in media from isolated islets of IKO and control mice treated with 10 nM KISS-54. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < .05) and **, P < .01. Bars, 30 μm.

To investigate whether Isl-1 mediates the effects of KISS-54 on insulin expression and secretion, 10 nM KISS-54 was administered to IKO and control mice via a caudal vein injection. After 6 hours, KISS-54 treatment resulted in a 49.75% decline in insulin mRNA and a 45.3% decline in serum insulin levels in control mice. However, KISS-54 treatment had no significant effect on insulin mRNA and serum insulin levels in IKO mice (Figure 6, C and D, P < .05). These findings demonstrate that the in vivo inhibition of insulin secretion by KISS-54 is at least partly mediated by Isl-1.

We isolated pancreatic islets from IKO and control mice (Figure 6E) as previously described (40) and also deleted Isl-1 in floxed mice by 4-OHT-induced Cre expression for 48 hours before the collection of pancreatic islets as previously reported (53). Isl-1 gene expression in islets from IKO mice and control mice was detected by RT-PCR. Results show that the expression levels of Isl-1 exons 3/4 decreased by 67.5% in IKO mice compared with the control levels (Figure 6F, P < .01). These findings are in agreement with our recent report (52). These results indicate efficient Cre Isl-1 excision in isolated islets of Isl-1MCM/F mice.

To identify whether the effects of KISS-54 treatment on insulin secretion are mediated by Isl-1 in isolated islets, 10 nM KISS-54 was added to 4-OHT-treated islets. Results demonstrate that KISS-54 treatment decreases insulin levels by 46.7% after 3 hours of treatment in control islets, but no significant effect of KISS-54 treatment on insulin secretion in IKO islets is seen (Figure 6G, P < .05).

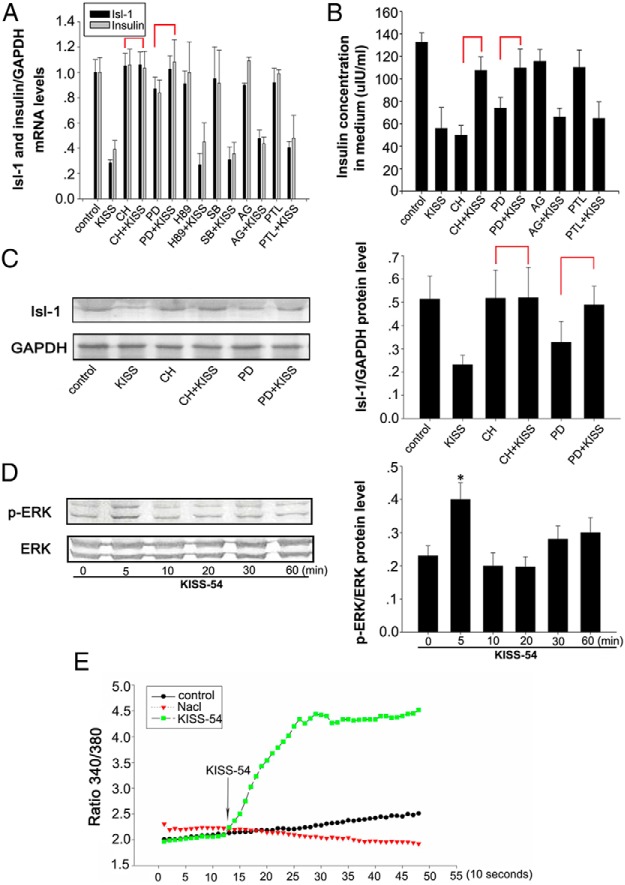

Effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion depend on PKC and ERK1/2 signaling pathways

To determine the downstream signaling of KISS-54, which affects Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion, NIT cells were incubated with 20 μM protein kinase A inhibitor N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide dihydrochloride (H89), the PKC inhibitor Chelerythrine chloride, the ERK1/2 antagonist PD98059, the P38 inhibitor SB203580, the JAK-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG490, or the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation suppressor Parthenolide for 1 hour before the addition of KISS-54 for 6 hours. The inhibition of Isl-1 mRNA and protein expression (Figure 7, A and C, P < .05) and insulin secretion (Figure 7B, P < .05) by KISS-54 were blocked by both CH and PD98059. Cultured cells were then exposed to 10 nM KISS-54 for up to 60 minutes and phosphorylated ERK1/2 was analyzed by Western blot. Results show that KISS-54 treatment significantly increases phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels after 5 minutes exposure (Figure 7D, P < .05). These results demonstrate that the effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion depended on PKC and ERK signals in NIT cells.

Figure 7.

Signaling pathways by which KISS-54 affects Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion. A, Relative mRNA levels of Isl-1 and insulin by RT-PCR in NIT cells after a 3-hour exposure to 10 nM KISS-54 and several inhibitors. B, Insulin levels measured by RIA in NIT cells after a 3-hour exposure to 10 nM KISS-54 and several inhibitors. C, Isl-1 protein levels detected by Western blot analysis in NIT cells after a 3-hour exposure to 10 nM KISS-54 and several inhibitors. D, Levels of phosphorylated ERK and total ERK proteins were detected by Western blot. E, Effects of 10 nM KISS-54 on [Ca2+](i) in confluent NIT cells. Representative recording of cytosolic calcium transients of Fura-2 AM loaded NIT cells treated with KISS-54 is shown. Relative changes in the concentration of cytosolic calcium are indicated by the 340/380 ratio (calcium bound Fura-2/free Fura-2). Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were recorded every 10 seconds. Data are shown as mean ± SD from three samples for each group. Significance differences are indicated by *, P < .05.

To investigate whether effects of KISS-54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion rely on influencing [Ca2+](i) in NIT cells, 10 nM KISS-54 was added to the medium, and [Ca2+](i) was detected using the Fura-2 method. Results show that KISS-54 induces an increase in intracellular calcium levels within about 10 seconds, which persists until 140 seconds (Figure 7E).

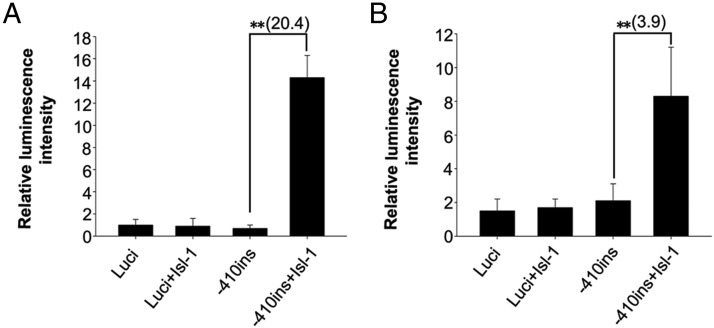

Isl-1 increases insulin promoter activity in 293T and NIT cells

To determine whether Isl-1 is involved in regulating insulin gene transcription, pXJ40-Myc-Isl-1 (54) was transfected into 293T cells and NIT cells with insulin promoter-luciferase vectors. Results from a dual-luciferase reporter assay show that Isl-1 enhances the activities of −410-insulin about 20.4-fold in 293T cells (Figure 8A, P < .01) and 3.9-fold in NIT cells (Figure 8B, P < .01). In contrast, Isl-1 overexpression did not change the luciferase activity of a pGL3.0-basic control vector. These results are in agreement with a previous report (18) that Isl-1 influences insulin levels through enhancing insulin promoter activity.

Figure 8.

Effects of Isl-1 expression vectors on transiently transfected insulin promoter reporter genes. The empty luciferase vector (luci) was transfected as a control. Effects of Isl-1 expression vectors on transiently transfected insulin gene promoters fused to luciferase reporter genes in 293T cells (A) and NIT cells (B). Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significance differences are indicated by **, P < .01.

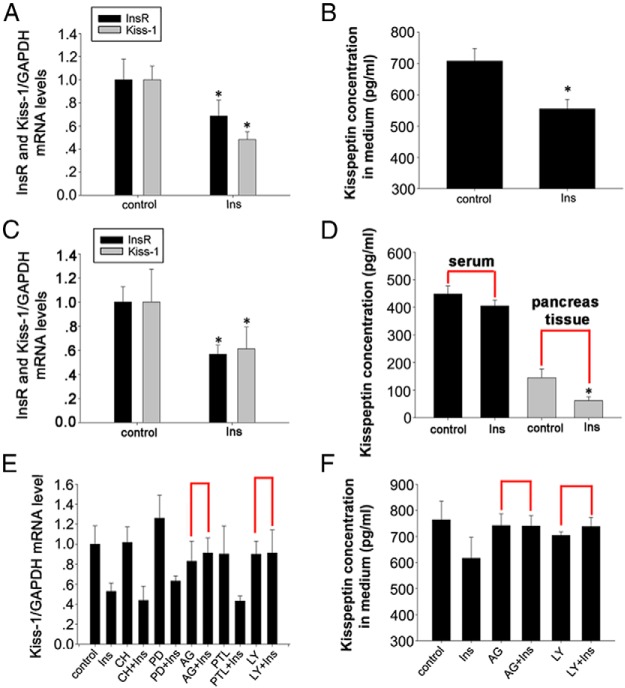

Insulin has feedback effects on kisspeptin expression and secretion through JAK and PI3K signaling pathways

Because pancreatic islet cells function to secrete kisspeptin, we wanted to identify whether insulin has a feedback loop regulating KISS-1 gene expression and kisspeptin secretion. We cultured NIT cells with 10−8 M insulin in DMEM and with 16.5 mM glucose for 12 hours. Results show that insulin significantly decreases KISS-1 mRNA levels in NIT cells and kisspeptin concentration in the medium, as detected by RT-PCR and ELISA, respectively (Figure 9, A and B, P < .05). Next, we administered insulin ip to mice at a dose of 5 IU/kg for 12 hours. KISS-1 mRNA levels in pancreas and kisspeptin concentrations in pancreatic tissue and serum were assessed. RT-PCR results show that insulin decreases KISS-1 mRNA levels. The ELISA results show that insulin significantly decreases kisspeptin concentration in pancreatic tissue (Figure 9, C and D, P < .05),but has no effect on serum concentrations of kisspeptin.

Figure 9.

Effects of the insulin signaling pathway on kisspeptin gene expression and secretion. A, Relative mRNA levels of insulin receptor and KISS-1 by RT-PCR in NIT cells after treatment with 10−8 M insulin. B, Kisspeptin concentration by an ELISA in culture medium of NIT cells after treatment with 10−8 M insulin. C, Relative mRNA levels of insulin receptor and KISS-1 detected by RT-PCR in the mouse pancreas, which has been ip injected with 5 IU/kg insulin. D, Concentration of kisspeptin by an ELISA in serum and pancreatic tissue of mice treated with 5 IU/kg insulin. E, Relative KISS-1 mRNA levels by RT-PCR in NIT cells after 12 hours of exposure to 10−8 M insulin and several inhibitors. Insulin was added after a 1-hour exposure to inhibitors. All final concentrations of inhibitors were 20 μM. F, Kisspeptin concentration by an ELISA in culture medium of NIT cells after 12 hours of exposure to 10−8 M insulin and several inhibitors. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significance differences are indicated by *, P < .05.

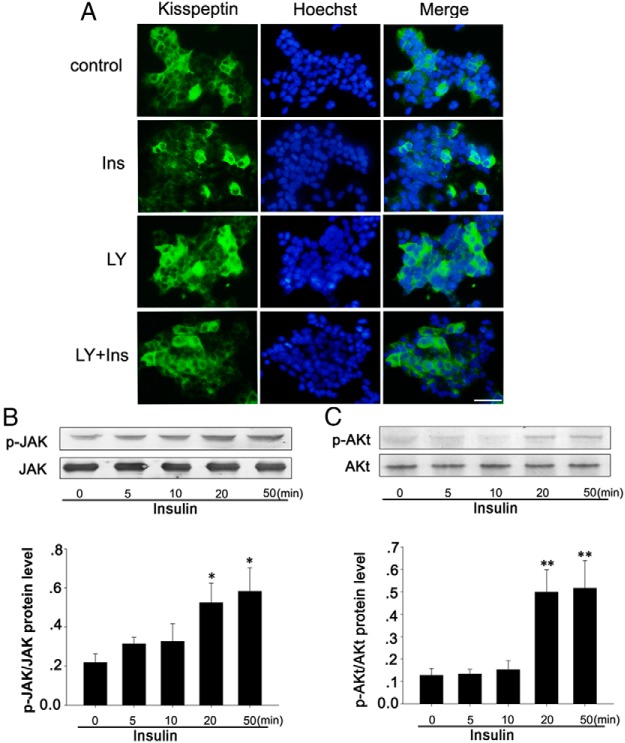

To determine signaling pathways downstream of insulin, which affects kisspeptin expression and secretion, we initially assessed the effects of insulin on insulin receptor gene expression in NIT cells and in the pancreas. Results confirm that insulin treatment down-regulates insulin receptor gene expressions in vitro and in vivo. To identify the signaling pathways downstream of insulin and its receptors that influence kisspeptin expression and secretion, the PKC inhibitor CH, ERK1/2 antagonist PD98059, JAK-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG490, STAT3 phosphorylation suppressor Parthenolide, or PI3K inhibitor 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one hydrochloride (LY) were added to cultured NIT cells before treatment with insulin as above. RT-PCR results show that both AG490 and LY treatments block insulin inhibition of KISS-1 gene expression and kisspeptin secretion (Figure 9, E and F).

We confirmed that LY treatment blocks the effects of insulin on kisspeptin expression by immunofluorescence in NIT cells. LY was added to cultured NIT cells before treatment with insulin as above. Results show that decreased kisspeptin expression in NIT cells, as evidenced by decreased immunofluorescence staining for kisspeptin after treatment with insulin, is blocked after exposure to LY (Figure 10A). We then treated NIT cells with 10−8 M insulin for 0, 5, 10, 20, and 50 minutes. Phosphorylated JAK and phosphorylated AKt were analyzed by Western blot. Results show that insulin significantly increases JAK phosphorylation after a 5-minute exposure, and this effect persists until 50 minutes (Figure 10B, P < .05). At the same time, insulin treatment significantly increases phosphorylated AKt protein levels after a 20-minute exposure, and this effect persists until 50 minutes (Figure 10C, P < .01). These findings indicate that the downstream signaling pathway by which insulin and its receptor affect the kisspeptin synthesis and secretion uses JAK and PI3K but not PKC or ERK1/2.

Figure 10.

Effects of the insulin signaling pathway on kisspeptin gene expression and secretion. A, Kisspeptin expression by immunofluorescence in NIT cells after 12h exposure to 10−8 M insulin and PI3K inhibitor LY. Insulin was added after a 1-hour exposure to LY. B, Phosphorylated JAK and total JAK levels in NIT cells after insulin treatment detected by Western blot. C, Phosphorylated AKt and total AKt levels in NIT cells after insulin treatment detected by Western blot. Data are shown as means ± SD from three samples for each group. Significance differences are indicated by *, P < .05) and **, P < .01). Bars, 30 μm.

Discussion

The regulating effects of the kisspeptins (5–9) and Isl-1 (30) on insulin secretion in the pancreas have been previously reported. However, a functional relationship between kisspeptins and Isl-1 has not been established for regulating insulin secretion. Our results demonstrate that Isl-1 and GPR54 are highly expressed in mouse pancreatic islet β-cells and NIT cells, and nearly all of the insulin-positive cells in the pancreas and NIT cells coexpress Isl-1 and GPR54. In addition, our functional experiments have demonstrated that exogenously added KISS-54 significantly inhibits mRNA expression of Isl-1 and insulin in the mouse pancreas and in cultured NIT cells. In addition, KISS-54 treatment significantly decreases global insulin levels and insulin secretion in NIT cells. However, KISS-54 treatment has no obvious effect on insulin degradation in different time points, and these results infer that KISS-54 may be through other manners to decrease insulin level rather than affect insulin degradation. Previous observations indicated that substantial amounts of insulin were degraded intracellularly in isolated pancreatic islets exposed to low glucose concentrations (55). Inversely, there was no insulin degradation in islets incubated at a high glucose concentration according to the previous report (56). The glucose concentration in our study belonged to high glucose concentration, the islet cells of this culture system was not easy to produce insulin degradation for outside stimulation. This supports the original results that KISS-54 reduced insulin level by inhibiting Isl-1 expression. In addition, some Isl-1 target genes that regulate insulin synthesis or/and secretion may be involved in the process according to the previous report (17). The interactions or cross talk among those signaling pathways and the related mechanisms are still waiting for further studies.

In the present study, we used an Isl-1 IKO mouse model to assess whether KISS-54's effect on insulin secretion is dependent on Isl-1. We used a conditional ablation strategy using a tamoxifen-inducible mER-Cre-mER recombinase cassette targeted to the Isl-1 locus (Isl-1MCM/F). First, we examined Isl-1 deletion efficiency in this model and demonstrated efficient ablation of Isl-1 in the pancreas and in cultured pancreatic islets (39). Furthermore, we compared blood glucose, plasma insulin levels, and glucose homeostasis between IKO and control mice. Ablation of Isl-1 results in impairment but not in complete loss of glucose and insulin tolerance. To better understand the pathophysiological basis of impaired glucose tolerance in Isl-1 IKO mice, we studied glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreas, and the results show that the insulin secretion response to glucose was reduced in Isl-1 IKO mice compared with control mice. At the same time, Isl-1 deficiency decreases insulin gene transcription and thus reduces insulin output in IKO mice. These collective results are in agreement with a previous report (30), although our inducible knockout efficiency was lower than the efficiency of conditional knockouts in that report.

Isl-1's involvement in insulin secretion is also supported by in vitro experiments showing that KISS-54 treatment does not have a significant effect on cultured pancreatic islet cells from IKO mice. In addition, the effects of KISS-54 on insulin gene expression and secretion are inhibited in IKO mice. These results suggest that Isl-1 is critical for mediating KISS-54's effects on insulin secretion and that Isl-1 affects the promoter activity of the insulin gene, a finding supported by a previous report (18). The effect of Isl-1 on insulin secretion is a complex regulatory process, and Isl-1 may indirectly affect insulin secretion by regulating other hormones, such as somatostatin. Isl-1 requires the cAMP response element binding protein to promote somatostatin expression in pancreatic islet cells (31), and somatostatin regulates insulin secretion by different signaling pathways (57–60). Insulin infused at a different concentration produce different effects on somatostatin secretion (61). These studies supports the notion of a negative feedback relationship between β- and δ-cells of the pancreatic islets, and under physiological circumstances their respective actions are inseparable. The specific mechanism still need to be further investigated.

Because different KISS-1/GPR54 signaling pathways have been proposed in different tissues (5, 27–29), we explored the downstream pathways of KISS-1/GPR54 signaling in NIT cells. There are reports that p38 MAPK and G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2, respectively, are involved in KISS-1/GPR54 signaling in the hypothalamus (22) and in human breast cancer cells (28). Phospholipase C, ERK1/2, and [Ca2+](i) take part in intracellular signaling pathways downstream of kisspeptin-10 in pancreatic islets (5). These studies suggest that KISS-1/GPR54 signaling is specifically and differentially regulated in different target tissues or cells. For determining the signaling pathway of KISS-54 effect on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion, we used specific inhibitors of PKC, protein kinase A, p38 MAPK, or ERK1/2 to see which inhibitor blocks the effects of KISS-1/GPR54 on Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion. Only the PKC inhibitor CH and the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 blocked KISS-54 inhibition of Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion. We found that KISS-54 treatment significantly increases phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels after a 5-minute exposure, and KISS-54 also induces an increase in [Ca2+](i). These results suggest that KISS-54 inhibits Isl-1 expression and insulin secretion through Ca2+-PKC-ERK1/2 pathways. However, calcium was a known secretagogue for insulin in some cases in pancreatic islets (5), and the report and our results appear to be inconsistent. There are reports that the activated [Ca2+](i) may play an opposite effect on the different conditions (62, 63). Under physiological conditions, the magnitude of change in [Ca2+](i) may not parallel the level of insulin release, suggesting that the role of [Ca2+](i) in the process of insulin release must be considered in concert with other cellular mechanisms (64). In our study, the effect of KISS-54 on insulin secretion was involved with the PKC-ERK signaling pathways and transcription factor Isl-1. In addition, the Isl-1 promoter did not contain the recognition site of ERK, and there may be other factors involved in the regulation of ERK on Isl-1. Further work is required to explore the factors responsible for differences between the observed effects in different conditions.

Some studies have shown that circulating kisspeptin comes from the central nervous system (65) and plays important roles in regulating insulin secretion. There are also reports that the pancreas produces kisspeptin (8, 22) and that insulin, in turn, acts as an autocrine/paracrine molecule to balance pancreatic hormone secretion (66, 67). Results presented here show that Isl-1 mediates the effects of kisspeptin signaling on insulin secretion. To assess whether there is a feedback loop regulating insulin's effect on kisspeptin secretion by pancreatic islets, we investigated changes in kisspeptin gene expression and its concentration after insulin treatment both in vivo and in vitro. Results confirm our hypothesis that insulin negatively regulates kisspeptin production and secretion in pancreatic islet cells. These interactions are affected by physiological or pathological criteria, such as global insulin, kisspeptin, and glucose levels. Further studies are required to fully understand interactions among kisspeptin, insulin, and related hormones within the pancreatic islet milieu.

Insulin and its receptor signaling pathways have been extensively studied and multiple signaling pathways have been proposed (68, 69). This is due to the multiple roles that insulin plays in its target tissues and cells. To identify the signaling pathway by which insulin affects kisspeptin secretion in pancreatic islets, specific inhibitors of PKC, MAPK, JAK, STAT3, or PI3K were used. Only the JAK inhibitor AG490 and the PI3K inhibitor LY blocked the effects of insulin on kisspeptin gene expression and secretion. In addition, insulin also significantly increases phosphorylated JAK and AKt protein levels at different time after insulin exposure. These findings suggest that insulin regulates kisspeptin secretion through JAK and PI3K-AKt signaling pathways, although the mechanism's details need to be further elucidated.

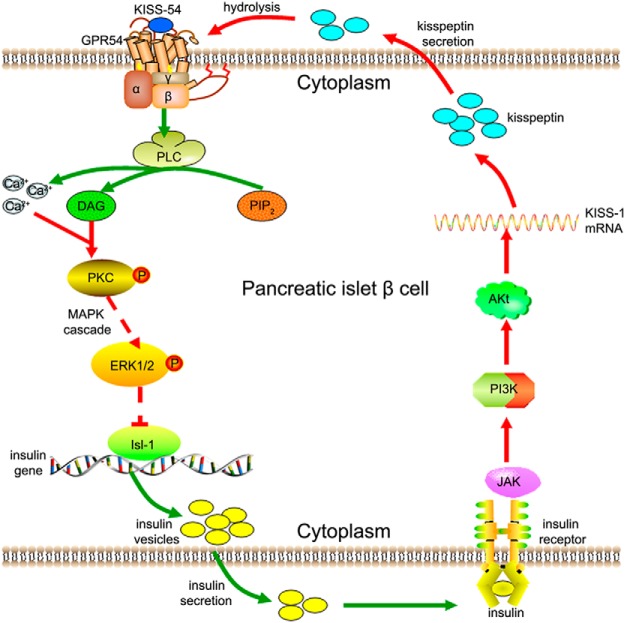

In conclusion, data presented here demonstrate a unique interaction between KISS-54 signaling and the transcriptional factor Isl-1. This cross talk appears to regulate the effects of KISS-54 on insulin secretion. In a negative feedback loop, insulin also inhibited KISS-54 production in pancreatic islet cells. Although actions of kisspeptin and insulin in pancreatic islet β-cells are accomplished through different signaling pathways (Figure 11), Isl-1 mediates the actions of both kisspeptin and insulin (Figure 11). These results are crucial for understanding the mechanisms regulating insulin secretion and are also very important for identifying novel targets for physiological or pharmacological intervention in diseases resulting from abnormal insulin secretion, such as type 2 diabetes.

Figure 11.

A model of Isl-1-mediated effects of kisspeptin on insulin synthesis and secretion. KISS-54 binds to GPR54 and activates its G-protein, which subsequently enhances phospholipase C (PLC) activation. Under PLC's effect, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis occurs to produce diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1, 4, 5-triphosphate (IP3), increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels. Subsequently, DAG-sensitive isoforms of PKC are activated, and phosphorylated PKC causes a downstream MAPK cascade reaction. Activated ERK1/2 affects Isl-1 mRNA and protein levels, and Isl-1 protein binds to the insulin promoter and enhances its activity to influence insulin synthesis and secretion. Extracellular insulin binds to its receptor and inhibits KISS-1 mRNA expression and kisspeptin secretion through JAK and PI3K-AKt signaling pathways. Extracellularly secreted kisspeptin is then hydrolyzed to produce KISS-54.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions included the following: J.L. and J.C. conceived and designed the experiments; J.C., R.F., Y.C., Y.L., and J.P. performed the experiments; R.F., Y.C., J.L., X.Z., and S.C. analyzed the data; J.C. and R.F. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; S.M.E. provided Isl-1MCM/+ and Isl-1F/F mice and was involved in the critical revision of the manuscript; and J.L. and J.C. wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31172287, 31172288, and 31372393 and National Key Program for Transgenic Breeding Grant 2013ZX08011-006.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31172287, 31172288, and 31372393 and National Key Program for Transgenic Breeding Grant 2013ZX08011-006.

Footnotes

- Ca2+(i)

- intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GPR54

- G protein-coupled receptor 54

- IKO

- inducible knockout

- JAK

- Janus kinase

- KISS

- kisspeptin

- LY

- 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one hydrochloride

- MafA

- V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A

- Ngn3

- neurogenin 3

- 4-OHT

- 4-hydroxytamoxifen

- p

- phosphorylated

- Pax4

- paired box transcription factor 4

- Pdx1

- pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- RT

- room temperature

- STAT3

- signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

References

- 1. Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jorns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL. Mechanisms of pancreatic β-cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes. 2005;54(suppl 2):S97–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seino S, Shibasaki T, Minami K. Dynamics of insulin secretion and the clinical implications for obesity and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2118–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Emilsson V, Liu YL, Cawthorne MA, Morton NM, Davenport M. Expression of the functional leptin receptor mRNA in pancreatic islets and direct inhibitory action of leptin on insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1997;46:313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kieffer TJ, Heller RS, Leech CA, Holz GG, Habener JF. Leptin suppression of insulin secretion by the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 1997;46:1087–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowe JE, King AJ, Kinsey-Jones JS, et al. Kisspeptin stimulation of insulin secretion: mechanisms of action in mouse islets and rats. Diabetologia. 2009;52:855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silvestre RA, Egido EM, Hernandez R, Marco J. Kisspeptin-13 inhibits insulin secretion without affecting glucagon or somatostatin release: study in the perfused rat pancreas. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vikman J, Ahren B. Inhibitory effect of kisspeptins on insulin secretion from isolated mouse islets. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(suppl 4):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hauge-Evans AC, Richardson CC, Milne HM, Christie MR, Persaud SJ, Jones PM. A role for kisspeptin in islet function. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2131–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bowe JE, Foot VL, Amiel SA, et al. GPR54 peptide agonists stimulate insulin secretion from murine, porcine and human islets. Islets. 2012;4(1):20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wahab F, Riaz T, Shahab M. Study on the effect of peripheral kisspeptin administration on basal and glucose-induced insulin secretion under fed and fasting conditions in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Horm Metab Res. 2011;43:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Campbell SC, Cragg H, Elrick LJ, Macfarlane WM, Shennan KI, Docherty K. Inhibitory effect of pax4 on the human insulin and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) promoters. FEBS Lett. 1999;463:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schisler JC, Jensen PB, Taylor DG, et al. The Nkx6.1 homeodomain transcription factor suppresses glucagon expression and regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in islet β cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7297–7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kataoka K, Shioda S, Ando K, Sakagami K, Handa H, Yasuda K. Differentially expressed Maf family transcription factors, c-Maf and MafA, activate glucagon and insulin gene expression in pancreatic islet α- and β-cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;32:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iacobazzi V, Infantino V, Bisaccia F, Castegna A, Palmieri F. Role of FOXA in mitochondrial citrate carrier gene expression and insulin secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brissova M, Shiota M, Nicholson WE, et al. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11225–11232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watada H, Kajimoto Y, Miyagawa J, et al. PDX-1 induces insulin and glucokinase gene expressions in αTC1 clone 6 cells in the presence of β-cellulin. Diabetes. 1996;45:1826–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Walp ER, May CL. Elevation of transcription factor Islet-1 levels in vivo increases β-cell function but not β-cell mass. Islets. 2012;4:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang H, Wang WP, Guo T, et al. The LIM-homeodomain protein ISL1 activates insulin gene promoter directly through synergy with BETA2. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahlgren U, Pfaff SL, Jessell TM, Edlund T, Edlund H. Independent requirement for ISL1 in formation of pancreatic mesenchyme and islet cells. Nature. 1997;385:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sander M, Sussel L, Conners J, et al. Homeobox gene Nkx6.1 lies downstream of Nkx2.2 in the major pathway of β-cell formation in the pancreas. Development. 2000;127:5533–5540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sosa-Pineda B, Chowdhury K, Torres M, Oliver G, Gruss P. The Pax4 gene is essential for differentiation of insulin-producing β cells in the mammalian pancreas. Nature. 1997;386:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, et al. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34631–34636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee JH, Miele ME, Hicks DJ, et al. KiSS-1, a novel human malignant melanoma metastasis-suppressor gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Irwig MS, Fraley GS, Smith JT, et al. Kisspeptin activation of gonadotropin releasing hormone neurons and regulation of KiSS-1 mRNA in the male rat. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaiser UB, Kuohung W. KiSS-1 and GPR54 as new players in gonadotropin regulation and puberty. Endocrine. 2005;26:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Ma D, et al. Kisspeptin directly stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release via G protein-coupled receptor 54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1761–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu X, Lee K, Herbison AE. Kisspeptin excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through a phospholipase C/calcium-dependent pathway regulating multiple ion channels. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4605–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pampillo M, Camuso N, Taylor JE, et al. Regulation of GPR54 signaling by GRK2 and β-arrestin. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:2060–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szereszewski JM, Pampillo M, Ahow MR, Offermanns S, Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV. GPR54 regulates ERK1/2 activity and hypothalamic gene expression in a Gα(q/11) and β-arrestin-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Du A, Hunter CS, Murray J, et al. Islet-1 is required for the maturation, proliferation, and survival of the endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 2009;58:2059–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leonard J, Serup P, Gonzalez G, Edlund T, Montminy M. The LIM family transcription factor Isl-1 requires cAMP response element binding protein to promote somatostatin expression in pancreatic islet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6247–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu J, Hunter CS, Du A, et al. Islet-1 regulates Arx transcription during pancreatic islet α-cell development. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15352–15360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuoka TA, Zhao L, Artner I, et al. Members of the large Maf transcription family regulate insulin gene transcription in islet β cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6049–6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barat-Houari M, Clement K, Vatin V, et al. Positional candidate gene analysis of Lim domain homeobox gene (Isl-1) on chromosome 5q11–q13 in a French morbidly obese population suggests indication for association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1640–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Claret M, Smith MA, Batterham RL, et al. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2325–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beall C, Piipari K, Al-Qassab H, et al. Loss of AMP-activated protein kinase α2 subunit in mouse β-cells impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and inhibits their sensitivity to hypoglycaemia. Biochem J. 2010;429:323–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choudhury AI, Heffron H, Smith MA, et al. The role of insulin receptor substrate 2 in hypothalamic and β cell function. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:940–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, et al. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun Y, Dykes IM, Liang X, Eng SR, Evans SM, Turner EE. A central role for Islet1 in sensory neuron development linking sensory and spinal gene regulatory programs. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1283–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li DS, Yuan YH, Tu HJ, Liang QL, Dai LJ. A protocol for islet isolation from mouse pancreas. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1649–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hussain MA, Porras DL, Rowe MH, et al. Increased pancreatic β-cell proliferation mediated by CREB binding protein gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7747–7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bock T, Pakkenberg B, Buschard K. Increased islet volume but unchanged islet number in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 2003;52:1716–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fu R, Liu J, Fan J, et al. Novel evidence that testosterone promotes cell proliferation and differentiation via G protein-coupled receptors in the rat L6 skeletal muscle myoblast cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hamaguchi K, Gaskins HR, Leiter EH. NIT-1, a pancreatic β-cell line established from a transgenic NOD/Lt mouse. Diabetes. 1991;40:842–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zajac M, Law J, Cvetkovic DD, et al. GPR54 (KISS1R) transactivates EGFR to promote breast cancer cell invasiveness. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huma T, Wang Z, Rizak J, et al. Kisspeptin-10 modulates the proliferation and differentiation of the rhesus monkey derived stem cell line: r366.4. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:135470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sawyer I, Smillie SJ, Bodkin JV, Fernandes E, O'Byrne KT, Brain SD. The vasoactive potential of kisspeptin-10 in the peripheral vasculature. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mahmoudi F, Khazali H, Janahmadi M. Interactions of morphine and Peptide 234 on mean plasma testosterone concentration. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:e12554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shearer JD, Coulter CF, Engeland WC, Roth RA, Caldwell MD. Insulin is degraded extracellularly in wounds by insulin-degrading enzyme (EC 3.4.24.56). Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E657–E664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sandberg M, Borg LA. Intracellular degradation of insulin and crinophagy are maintained by nitric oxide and cyclo-oxygenase 2 activity in isolated pancreatic islets. Biol Cell. 2006;98:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cordes CM, Bennett RG, Siford GL, Hamel FG. Redox regulation of insulin degradation by insulin-degrading enzyme. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen J, Fu R, Cui Y, et al. LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Isl-1 mediates the effect of leptin on insulin secretion in mice. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12395–12405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu HL, Wang Y, Zhang P, et al. Reversible immortalization of rat pancreatic β cells with a novel immortalizing and tamoxifen-mediated self-recombination tricistronic vector. J Biotechnol. 2011;151:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hao A, Novotny-Diermayr V, Bian W, et al. The LIM/homeodomain protein Islet1 recruits Janus tyrosine kinases and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and stimulates their activities. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1569–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Borg LA, Schnell AH. Lysosomes and pancreatic islet function: intracellular insulin degradation and lysosomal transformations. Diabetes Res. 1986;3:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Monic S. Intracellular degradation of insulin in pancreatic islets. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. 2007;1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schwetz TA, Ustione A, Piston DW. Neuropeptide Y and somatostatin inhibit insulin secretion through different mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E211–E221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Strowski MZ, Parmar RM, Blake AD, Schaeffer JM. Somatostatin inhibits insulin and glucagon secretion via two receptors subtypes: an in vitro study of pancreatic islets from somatostatin receptor 2 knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yao CY, Gill M, Martens CA, Coy DH, Hsu WH. Somatostatin inhibits insulin release via SSTR2 in hamster clonal β-cells and pancreatic islets. Regul Pept. 2005;129:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hsu WH, Xiang HD, Rajan AS, Kunze DL, Boyd AE 3rd. Somatostatin inhibits insulin secretion by a G-protein-mediated decrease in Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the β cell. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:837–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Honey RN, Fallon MB, Weir GC. Effects of exogenous insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin on islet hormone secretion in the perfused chicken pancreas. Metabolism. 1980;29:1242–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mao Z, Bonni A, Xia F, Nadal-Vicens M, Greenberg ME. Neuronal activity-dependent cell survival mediated by transcription factor MEF2. Science. 1999;286:785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Youn HD, Sun L, Prywes R, Liu JO. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by Ca2+-induced release of the transcription factor MEF2. Science. 1999;286:790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Draznin B. Intracellular calcium, insulin secretion, and action. Am J Med. 1988;85:44–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pita J, Barrios V, Gavela-Perez T, et al. Circulating kisspeptin levels exhibit sexual dimorphism in adults, are increased in obese prepubertal girls and do not suffer modifications in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty. Peptides. 2011;32:1781–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Koranyi L, James DE, Kraegen EW, Permutt MA. Feedback inhibition of insulin gene expression by insulin. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:432–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yu J, Berggren PO, Barker CJ. An autocrine insulin feedback loop maintains pancreatic beta-cell 3-phosphorylated inositol lipids. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2775–2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bollag GE, Roth RA, Beaudoin J, Mochly-Rosen D, Koshland DE Jr. Protein kinase C directly phosphorylates the insulin receptor in vitro and reduces its protein-tyrosine kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5822–5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]