Abstract

Gap junction channels facilitate the intercellular exchange of ions and small molecules, a process that is critical for the function of many different kinds of cells and tissues. Recent crystal structures of channels formed by one connexin isoform (connexin26) have been determined, and they have been subjected to molecular modeling. These studies have provided high-resolution models to gain insights into the mechanisms of channel conductance, molecular permeability, and gating. The models share similarities, but there are some differences in the conclusions reached by these studies. Many unanswered questions remain to allow an atomic-level understanding of intercellular communication mediated by connexin26. Because some domains of the connexin polypeptides are highly conserved (like the transmembrane regions), it is likely that some features of the connexin26 structure will apply to other members of the family of gap junction proteins. However, determination of high-resolution structures and modeling of other connexin channels will be required to account for the diverse biophysical properties and regulation conferred by the differences in their sequences.

Keywords: gap junction channel, connexin26, crystal structure, membrane topology, intercellular communication

Introduction

Intercellular communication through gap junction channels is critical for integrating the functions of cells in the tissues of all multicellular organisms by allowing direct exchange of ions and small molecules. In vertebrates, gap junctions are formed by members of a family of proteins that are called connexins (Cx). The importance of gap junctions is supported by the wide range of abnormalities linked to connexin mutations or caused by disrupting connexin expression (including deafness, neuropathies, arrhythmias, cataracts, skin diseases, lymphedema, and impaired development) (reviewed in 1– 3). Understanding the structures of the channels formed by connexins is critical for elucidating gap junction channel permeability and regulation at an atomic level.

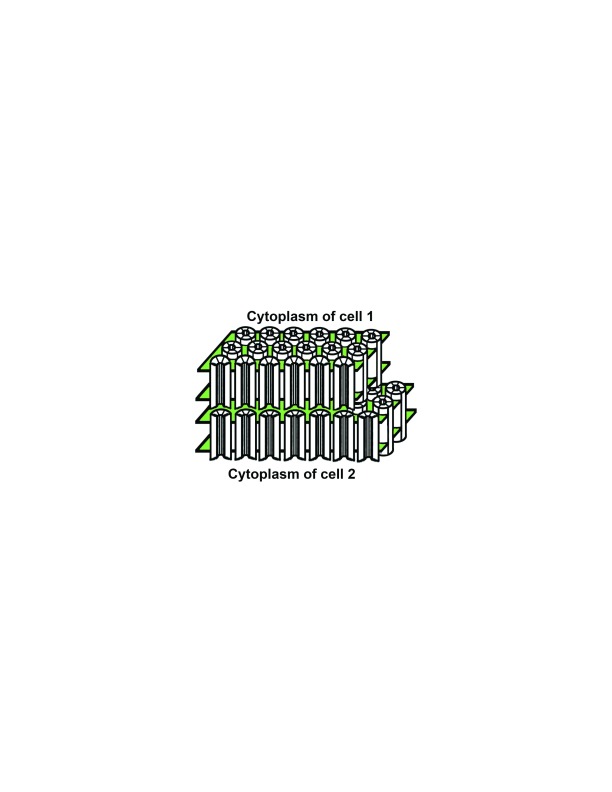

Gap junctions were originally defined based on structure (appearance in electron micrographs) 4– 6. They also were among the first membrane channels for which low-resolution three-dimensional structural analyses were accomplished. Nearly 40 years ago, isolated liver gap junctions were subjected to electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction crystallography followed by image analysis 7, 8. These studies led to a model in which the gap junction channel is formed of two hemichannels (one contributed by each of the apposing cells) that dock to each other (“head-to-head”); each hemichannel (also called a connexon) contains six subunit proteins (connexins) that surround the central water-filled pore ( Figure 1). Over subsequent years, this model was refined by additional structural studies of two-dimensional arrays of channels in isolated gap junctions 9, 10.

Figure 1. Diagram of the gap junction structure.

A gap junction is a cluster of intercellular channels formed by head-to-head apposition of connexin hemichannels within the plasma membranes of adjacent cells. The hemichannels are hexameric assemblies of connexin proteins surrounding a central aqueous pore and are depicted as cylinders formed of six subunits. The boundaries of the plasma membrane are illustrated in green. The model is based on Makowski et al. 8.

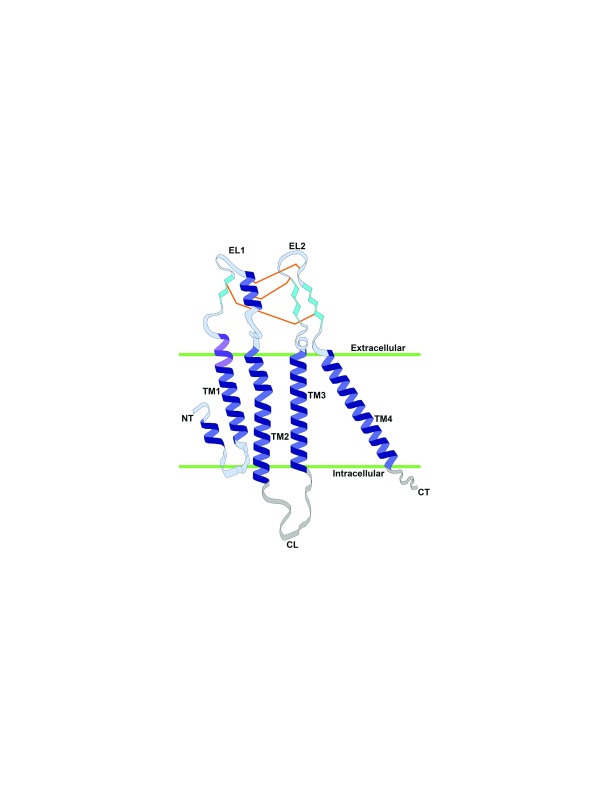

Cloning of DNA sequences and predictions regarding the encoded polypeptides suggested that all of the connexins had similar membrane topologies and each contained four transmembrane domains (TMs) 11– 14. In the connexin membrane topology, the N-terminus (NT), a cytoplasmic loop (CL) between TM2 and TM3, and the C-terminus (CT) are cytoplasmic, while two domains, EL1 (between TM1 and TM2) and EL2 (between TM3 and TM4), are extracellular ( Figure 2). This connexin topology model was supported by immunoelectron microscopy studies mapping different peptide sequences in the connexin molecule 15, 16. A large number of functional studies involving site-directed mutagenesis and physiological characterization of the properties of expressed mutant connexins were performed based on these models. Electron cryo-crystallography allowed determination of the structure of channels formed by a truncated connexin43 (Cx43), lacking most of the CT, at 7.5 Å resolution; it showed the presence of 24 transmembrane helices in each hemichannel, consistent with the initial models 17. NMR analysis of synthetic peptides showed the presence of short α-helices within the N-terminal domains of several connexins 18– 20.

Figure 2. Two-dimensional representation of the structure of a connexin26 (Cx26) monomer within the membrane.

The structure of Cx26 is indicated based on Maeda et al. 21. Protein secondary structure is colored as follows: deep blue, α-helix; purple, parahelix; turquoise, β-sheet. Amino acids whose side chains are included in the Cx26 structure but are not part of a helix or β-sheet are colored light blue; disordered regions are depicted in gray pattern. Disulfide bonds formed between cysteine residues are indicated by orange lines. The boundaries of the plasma membrane (green lines) delimiting the extracellular and intracellular sides are based on Kwon et al. 23. Domains within the connexin monomer are also indicated: CL, cytoplasmic loop; CT, C-terminus; EL1 and EL2, extracellular loops 1 and 2; NT, N-terminus; TM1–TM4, transmembrane domains 1–4.

Connexin26 crystal structure

The understanding of gap junction structures was significantly advanced in 2009, when Maeda and colleagues published a 3.5 Å X-ray crystal structure of the human connexin26 (Cx26) channel 21. This structure confirmed many aspects of the existing gap junction channel models, including the dodecameric channel structure (formed of two hexameric hemichannels) and the presence of four α-helical TMs in each connexin monomer. The Cx26 structure showed that the permeation pathway through the hemichannel contained a positively charged cytoplasmic entrance, a funnel, a negatively charged path, and an extracellular cavity. The structure resolved a previous controversy by showing that the major pore-lining helix was TM1. However, the structure did not allow resolution of the positions of the side chains of some critical N-terminal amino acids. The CL (residues 110–124) and the short cytoplasmic carboxyl terminal segment (218–226) could not be modeled because of a lack of order in these regions. Many features of the Cx26 gap junction channel have been confirmed by an independent crystal structure 22.

The Cx26 structure has provided a basic atomic model to investigate the function and regulation of Cx26 channels in more detail. In addition, because high-resolution structures of other members of the connexin family have not yet been determined, it has been utilized to predict features of other connexin channels and the consequences of their mutants.

Structural insights into channel permeability and conductance

Availability of the Cx26 structure has driven further investigations of gap junction channel permeability. Because this structure contains an unobstructed permeation pathway with a pore diameter of ~14 Å (based on minimal center-to-center distances of opposed heavy atoms and without considering atom diameters) and because crystallization was performed at neutral pH and in the absence of divalent ions, Maeda et al. suggested that it was an open channel 21. However, Kwon et al. 23 pointed out that Maeda et al. 21 may have overestimated the pore diameter because their Cx26 structure does not contain coordinates of the N-terminal methionine (which is acetylated as determined by mass spectrometry 24) or of the side chains of several N-terminal domain amino acids that may contribute to restricting the aqueous pore. When they accounted for these additional features, Kwon et al. estimated that the pore of the published Cx26 structure would actually be <6 Å, a size too small to allow the passage of hydrated ions or the molecular tracers that permeate through gap junction channels 23. To generate a structure that may more accurately represent the “open” configuration, Kwon et al. used molecular dynamics simulations to equilibrate the Cx26 hemichannel after completion of the structure by the addition of the missing residues; then, they utilized Brownian dynamics to test the validity of the equilibrated model by comparing the current-voltage relation of the refined atomic structure calculated with grand canonical Monte Carlo Brownian dynamics with that of the experimental data 23. This equilibrated structure has an average pore diameter of 12.8 Å (at the position of M1). Similar pore diameters were obtained by Zonta et al. for human Cx26 and Cx30 using molecular dynamics 25.

The cytoplasmic channel entrance is formed by parts of TM2 and TM3, where a concentration of positively charged amino acid side chains may facilitate the accumulation of negatively charged permeant molecules 26. If this aspect of the Cx26 structure was a major determinant of channel permeability for all connexin channels, they should all preferentially permeate negatively charged molecules. However, the K/Cl permeability ratio for intercellular Cx26 channels is about 2.6 27. In addition, several other connexins have greater permeabilities for positively than for negatively charged ions and larger molecules 28– 30. In their modeling, Kwon et al. concluded that co- or post-translational modification (acetylation) of the N-terminal methionine and of several lysine residues at the cytoplasmic pore entrance may greatly influence charge selectivity 23.

The pore funnel is formed by six NT helices that gradually narrow the pore diameter 21. The charges of amino acid side chains in the NT region are determinants of the unitary conductance and charge selectivity of connexin channels, as demonstrated by mutagenesis studies creating substitutions or deletions in the NT that produced alterations of these properties 31– 37. Zonta et al. modeled Cx30 channels and concluded that differences in unitary conductance between Cx26 and Cx30 might result from differences in positions and charges of ion sieves within their pores 25. Modeling based on the Cx26 structure has been used to develop atomic level interpretations of the results from studies of disease-related NT mutants of other connexins like Cx46 38, 39.

Additional negative charges along the permeation pathway (contributed by side chains of pore-lining residues, especially at the TM1/E1 boundary) may also contribute to channel properties 40– 45. This region may play a major role in determining the permeability of Cx26 channels. It is possible that a positively charged permeant undergoes sequential, transient interactions with negatively charged side chains as it progresses through the pore until it reaches the cytoplasmic entrance of the connexin channel in the adjacent cell. Computational methods to simulate the movement of a permeant and an impermeant sugar molecule through the Cx26 gap junction channel led to the conclusion that their selective permeation may be influenced by hydrogen bonding, interaction with K +, and “entropic factors arising from permeant flexibility” 46.

Molecular dynamics simulations of the human Cx26 hemichannel identified a water pocket (also termed intracellular or IC pocket) located between the four TM domains of each connexin monomer, totaling six water pockets per hemichannel 47. The water in these pockets may be able to move between the pocket and the main channel via a small aperture below the NT domain; however, the diffusion coefficient of water molecules in the pocket varies depending on the connexin monomer, and the residence of the water molecules is different in each pocket. The water pocket has been hypothesized to have a role in hemichannel activity (including permeability) 47.

A tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis study revealed extensive interactions between TMs in Cx32 that are critical for gap junction function 48. This study suggested that the Cx32 gap junction channel has a similar architecture of TMs to both the Cx26 structure (on which it was based) and its equilibrated molecular dynamics model, including the presence of IC pockets 48.

Docking of hemichannels

Gap junction channels are unique when compared to other channels in that they span the plasma membranes of two adjacent cells and allow intercellular communication. The formation of the gap junction channel requires docking between two hemichannels and the production of a tight seal to separate the channel interior from the extracellular milieu. Given the membrane topology of connexins and that the channel spans two plasma membranes, docking must involve the extracellular domains.

Several studies have contributed to elucidating the structure of the gap junction channel in the extracellular gap. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis suggested that the extracellular domains contain anti-parallel β-sheets and that the ELs from one hemichannel interdigitate with those of the opposing hemichannel, forming a β-barrel extension of the gap junction channel at the docking interface 49. Cryo-electron microscopy of a truncated Cx43 channel showed that the extracellular region was double layered, including a continuous inner layer of protein capable of forming a tight seal 17. Specific EL1-EL1 and EL2-EL2 intercellular interactions have been identified in the Cx26 crystal structure 21. In EL1, N54 forms hydrogen bonds with the main-chain amide of L56 from the opposite connexin in the opposed hemichannel, and Q57 forms hydrogen bonds with Q57 of the diagonally opposite connexin in the opposed hemichannel. In EL2, K168, D179, and the main-chain carbonyl groups of T177 and N176 form hydrogen bonds and salt bridges with the opposite connexin in the opposed hemichannel. Together, these interactions and those between the connexin monomers forming each hemichannel result in the formation of a tight, double-layered wall spanning the extracellular gap, connecting the opposed hemichannels.

The docking of other connexins may involve similar interactions to those identified in Cx26. Among the human connexins, the amino acid corresponding to Q57 is absolutely conserved, and those corresponding to N54 and D179 are well conserved (differing in only two or three of the 20 family members). However, amino acids corresponding to L56, K168, N176, and T177 diverge in many of the connexins. To ensure the formation of a tight seal between apposed hemichannels formed by other members of the family, there may be compensatory substitutions of the corresponding amino acid residues to restore hydrogen bond formation with the differing interacting amino acids, or, alternatively, there may be compensatory interactions between surrounding residues that differ from those of Cx26.

Knowledge of the amino acid residues important for docking has helped elucidate the molecular mechanism of malfunction of some disease-associated connexins. In their studies of a cataract-linked mutant (Cx46N188T), which forms functional hemichannels (but not intercellular channels), Schadzek et al. constructed models of Cx46 based on the Cx26 structure that allowed them to conclude that the mutated amino acid is critical for the docking of hemichannels through the formation of hydrogen bonds with the opposing hemichannel 50. The mutated amino acid in Cx46 (N188) corresponds to N176 of Cx26. A mutant of Cx32 at the corresponding position (Cx32N175D) causes X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and, similarly, does not form functional homotypic gap junction channels 51.

Pairing of hemichannels containing different connexins requires specificity of connexin interactions to form functional heterotypic intercellular channels. This process has been studied by bringing cells (or Xenopus oocytes) expressing one connexin subtype into apposition with cells (or Xenopus oocytes) expressing a different connexin subtype and assessing gap junctional conductance. Some combinations of connexins result in functional channels (i.e. compatible connexins) and some do not (i.e. incompatible connexins). For example, Cx26 forms heterotypic channels with Cx32, but not with Cx40 or Cx43 (see a more comprehensive diagram summarizing compatible and incompatible connexins in 52). Amino acids in EL2 have been implicated in determining connexin compatibility for the formation of functional heterotypic channels, based on the results of expression studies of chimeric connexins in which the EL1 or EL2 domains were replaced with those from a different, incompatible connexin 53, 54. Homology modeling and studies of the ability of Cx32 mutants to form heterotypic channels with Cx26 suggest that at least four hydrogen bonds between a pair of opposed EL2 domains are required for proper docking and functional heterotypic channel formation 51.

Structural insights into channel gating

The opening and closing of connexin channels (and hemichannels) can be modulated by voltage, pH, divalent cations, a variety of chemicals, and co-/post-translational modifications. Connexin channels exhibit two functionally distinguishable voltage-dependent gating mechanisms: (1) V j or fast gating, in which the channel closes to a substate as determined by a single connexin subunit 55, and (2) “loop” or slow gating, in which a cooperative, concerted process fully closes the channel 56. For both voltage-sensitive mechanisms, the voltage sensed is that within the pore and, because of this, there is interaction between the voltage-sensitive gating mechanisms. Snipas et al. recently analyzed this quantitatively and generated a stochastic 36-state model of gap junction channel gating 57. The variety of factors that modulate connexin channel function suggests that the amino acids involved in sensing them are different. Once a factor is sensed, a response must be transduced, likely through an initial conformational change. Since the sensing amino acids differ, the initial conformational change would be expected to be relatively specific. However, it is unclear whether the initial changes are followed by conformational changes that are specific for different factors or whether the changes triggered by different factors share some similarities before converging upon a common mechanism that gates the channel closed. These issues have been illustrated by studying the regulation of mutant Cx26 hemichannels. Wild-type Cx26 hemichannel activity is inhibited by both Ca 2+ and acidification; however, while Ca 2+ regulation is retained by Cx26N14K and Cx26A40V hemichannels (although modestly impaired in Cx26A40V), pH regulation is absent in Cx26N14K and severely impaired in Cx26A40V 58, 59. Thus, although both Ca 2+ and pH act on the loop gate, they promote different conformational pathways leading to closure of this gate 59.

Electron crystallographic analysis of a Cx26 mutant (Cx26M34A) showed a “plug” within the mouth of the channel; this density was decreased in a Cx26 mutant with a deletion of several amino acids within the N-terminal region, suggesting that connexin channels might be closed by a “plug gating” mechanism in which the NTs physically block the channel pore 60. Because a large body of data has shown that amino acids within the NT serve as a voltage sensor and determine the polarity of V j (or fast) gating 55, 61, 62, it is tempting to propose that this “plug gating” mechanism could explain this voltage-dependent gating process. However, “plug gating” may not explain V j (or fast) gating because Cx26M34A hemichannels exhibit a low level of conductance (when paired with wild-type Cx26 hemichannels) and show normal V j gating in this asymmetric configuration 60. Moreover, in the tryptophan-scanning study, it was suggested that gating occurs as a result of global conformational changes around TM1 48.

Loop (or slow) gating of connexin hemichannels and intercellular channels depends on amino acids at the TM1/EL1 interface 63, 64. Based on molecular dynamics simulations, Kwon et al. suggested that the 3 10 helix located in this region (which they termed the “parahelix” because it does not strictly fit the structural requirements of a 3 10 helix) contains charged residues that might act as a voltage sensor and that concerted movements of this region and other parts of the molecule might close the hemichannel 56. Interactions involving the NT may also be involved in loop gating, as implicated by studies of deafness-associated mutations of Cx26 involving substitutions of N14 59.

Gap junction channels can also be closed by acidification. For some connexins, like Cx43 (but not others, like Cx45), acidification-induced closure of the channel may occur through a particle-receptor mechanism in which the C-terminal domain binds to residues within the CL 65– 68. Unfortunately, the structural basis for this form of channel closure is not well understood, since high-resolution X-ray and electron microscopy structures are not available for these connexins. NMR has been used to study the solution structures of the C-terminal domains of Cx43 (full-length or shorter peptides) and have identified α-helical regions connected by more flexible loops that may change conformation in response to pH 69. Interestingly, a direct interaction between the CL and the CT of Cx26 is necessary to keep the channels open; its destabilization by protonated aminosulfonates leads to channel closure 70.

To gain insights into gating by divalent cations, Bennett et al. determined the X-ray structures of the human Cx26 gap junction channel crystallized in the presence or absence of calcium ions 22. These two structures showed rather small conformational differences but identified calcium coordination sites (the carboxylate of E47 and carbonyl oxygen of G45 from one monomer and the carboxylate of E42 in the adjacent monomer). These amino acids are located near the beginning of the extracellular part of the channel. An earlier study had shown ɤ-carboxylation of E42 and E47 of Cx26 by mass spectrometry and suggested that this modification generated high-affinity Ca 2+-binding sites 24. Quantum chemistry computations performed by Zonta et al. had also suggested that Ca 2+ binds to the ɤ-carboxylated E47, altering the local structure of the Cx26 hemichannel and preventing stabilizing interactions with R75 from the same monomer and R184 from an adjacent monomer 71. These studies differ in the proposed mechanisms of Ca 2+-dependent block: Bennett et al. suggested that binding of calcium ions generates an electrostatic barrier that inhibits the permeation of cations through the pore 22; in contrast, Zonta et al. proposed that extracellular Ca 2+ binding produces structural alterations 71. It is unclear whether the Ca 2+ electrostatic barrier mechanism (which does not produce steric occlusion of the pore) or the structural alterations (obtained by quantum chemistry computations) could explain loop gating.

While the crystallization analysis of Ca 2+ interactions with Cx26 considered dodecameric intercellular channels 22, many of the functional studies of Ca 2+ block used physiological and biophysical approaches to study connexin hemichannels. Blockade of undocked connexin hemichannels has obvious biological importance as a mechanism to prevent cytotoxicity; opening of unopposed hemichannels can be prevented by their exposure to the substantial concentrations of Ca 2+ normally present extracellularly. Although the Ca 2+ block of intercellular channels and the block of hemichannels both involve amino acid residues in the ELs, these processes may not occur through identical mechanisms because docking could alter the spatial orientations of some residues and their side chains, affecting the Ca 2+ binding sites.

Physiological dissection of the mechanisms of Ca 2+-dependent block of Cx26 channels was stimulated by the discovery that some patients with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness disorder have mutations (especially substitutions of D50) that cause aberrant opening of hemichannels due to Ca 2+ insensitivity 43, 72, 73. Expression studies suggest that Ca 2+ stabilizes the closed state of wild-type Cx26 hemichannels, and a negative charge at amino acid 50 is required for this stabilization 43, 73. Some (but not all) data suggest that D50 forms a salt bridge with the nearby K61 (from an adjacent connexin subunit) that stabilizes the open state of the Cx26 hemichannel in low external Ca 2+, an interaction that is disrupted in high extracellular Ca 2+ 43, 73. Although data supporting a D50-Q48 interaction have also been reported, this interaction would not make a major contribution to stabilizing the open state in low or absent external Ca 2+ 74. Lopez et al. used molecular dynamics simulations to identify Ca 2+ interaction sites and their effects on the Cx26 hemichannel 75. Their data suggest that E47 and D50 are part of the Ca 2+ binding site and that there is an electrostatic network near the extracellular entrance of the pore (including the D50-K61 salt bridge and interactions involving D46, E47, R75, R184, and E187) 75. Their modeling was supported by mutagenesis of critical residues in Cx26 and of the corresponding residues in Cx46 (suggesting generalizability). Furthermore, Lopez et al. concluded that the Ca 2+-sensing ring is distinct from the gate and that the gate localizes further into the pore (below G45) 75. Earlier studies of Cx46 hemichannels indicate that its Ca 2+ gate is extracellular to L35 (corresponding to M34 in Cx26) 76. The results from these studies would suggest that the Ca 2+-responsive gate in Cx26 localizes between M34 and G45.

Other regions in other connexin isoforms may also be responsible for or contribute to channel gating by divalent cations. Studying Cx32 hemichannels, Gómez-Hernández et al. concluded that Ca 2+ bound to D169 and D178 in EL2, blocking both voltage-gated opening to the higher conductance open state (90 pS) and ion conduction through partially open (18 pS) hemichannels 77. The charge at the amino acid corresponding to D178 is conserved in 18 of the 20 family members, but that of D169 is not. Whether this is a common mechanism for Ca 2+-dependent regulation of a subset of connexins as suggested by the authors remains to be evaluated. Other physiological studies have suggested that Ca 2+ itself or Ca 2+/calmodulin bind near the cytoplasmic face of the channel to gate channels closed 78– 81. Ca 2+/calmodulin binding sites have been identified for several different connexins within their NT, CL, or CT domains, and the α-helical content of CL or CT peptides containing the putative calmodulin binding sites increases after binding calmodulin 82. Because both the CL and the CT also possess unstructured regions, it is possible that calmodulin binding leads to movements of these domains that may obstruct the pore or may allow more stable interactions of the structured regions with other cytoplasmic domains and obstruct the pore.

Additional NMR studies have shown that phosphorylation (in response to src or other kinases) causes structural changes of the C-terminal domain that may contribute to channel closure or may alter interactions with cellular proteins 83. NMR data have also demonstrated structural differences in the CT domains of different connexins 84. This result was predictable because the amino acid sequence of the CT domain is highly divergent among members of the connexin family. It had previously been proposed that the extensive differences in the CT sequences of different connexin isoforms likely contribute to differences in channel regulation. The roles played by the structured regions of the CT domain in differential regulation of connexin channels remain to be elucidated.

Summary and unresolved issues

The different Cx26 crystal structures and the models derived from simulations represent substantial advances for understanding gap junctions. They show many similar features, but they also have some inconsistencies. Currently, simulations produced using the equilibrated Cx26 structure account for experimental data more closely than do the crystal structures. It is possible that ions and larger molecules go through the pore as predicted by the molecular dynamics simulations and that several factors (including charge and/or post-translational modification of the side chains) contribute to determining selective ion/molecular permeability (as explored by Luo et al. 46).

It is still unclear what determines Ca 2+ gating: structural/conformational changes or electrostatic barriers (or both). It is uncertain whether the mechanism involved is similar in hemichannels and in intercellular channels since docking may induce alterations in the positions and involvement of some of the amino acids. Different studies have implicated several amino acids and their interactions in Ca 2+-dependent regulation of channel activity, suggesting that this is a complex process. A conformational change of the ELs induced by interaction of Ca 2+ with D50 may be the initial step in the closure of Cx26 hemichannels 75. Further investigations will be required to resolve the discrepancies and to understand fully all the steps involved.

A future goal will be to develop an accurate representation of the gap junction channel (and hemichannel) in different states (fully open and conducting versus functional substates versus different closed states) under normal conditions and after being gated open or closed by different agents/factors. These studies may clarify whether different gating agents lead to similar or differing conformational changes.

It is uncertain which features of the Cx26 structure will be generalizable to all of the other connexins. Since 20 members of the human connexin family form channels with distinct properties and are differentially expressed in various organs, it will be important to elucidate the channel structures of additional members of the connexin family. Previous studies have suggested that there are critical differences among connexin channels from different subfamilies (e.g. Cx32 versus Cx43 versus Cx36). Biochemical studies have shown dissimilarities among subfamilies, even in conserved regions like the ELs, where the positions of the cysteines forming disulfide bonds may differ 49, 85. Since the connexins differ in their primary sequences, the pore-lining amino acids and the charges (and modifications) of their side chains are likely to differ; these differences can influence the characteristics of the pore, resulting in different channel properties (including charge selectivity, size permeability, and single channel conductance). Mathematical modeling suggests that pairing of hemichannels made of different connexins with differences in their pore shapes might account for asymmetrical flux of large charged molecules through heterotypic gap junction channels 86. Understanding the structures of different connexin channels and determinants of their specific properties could have valuable therapeutic benefits, such as facilitating the design of inhibitors targeting a particular connexin.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Donglin Bai, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

Thaddeus Bargiello, Dominic P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA

Juan Sáez, Departamento de Fisiología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Instituto Milenio, Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencias de Valparaíso, Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile

Funding Statement

Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY08368.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 3 approved]

References

- 1. Dobrowolski R, Willecke K: Connexin-caused genetic diseases and corresponding mouse models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(2):283–95. 10.1089/ars.2008.2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfenniger A, Wohlwend A, Kwak BR: Mutations in connexin genes and disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41(1):103–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beyer EC, Ebihara L, Berthoud VM: Connexin mutants and cataracts. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:43. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dewey MM, Barr L: Intercellular Connection between Smooth Muscle Cells: the Nexus. Science. 1962;137(3531):670–2. 10.1126/science.137.3531.670-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robertson JD: The occurrence of a subunit pattern in the unit membranes of club endings in Mauthner cell synapses in goldfish brains. J Cell Biol. 1963;19(1):201–21. 10.1083/jcb.19.1.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Revel JP, Karnovsky MJ: Hexagonal array of subunits in intercellular junctions of the mouse heart and liver. J Cell Biol. 1967;33(3):C7–C12. 10.1083/jcb.33.3.C7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caspar DL, Goodenough DA, Makowski L, et al. : Gap junction structures. I. Correlated electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. J Cell Biol. 1977;74(2):605–28. 10.1083/jcb.74.2.605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makowski L, Caspar DL, Phillips WC, et al. : Gap junction structures. II. Analysis of the X-ray diffraction data. J Cell Biol. 1977;74(2):629–45. 10.1083/jcb.74.2.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Unwin PN, Zampighi G: Structure of the junction between communicating cells. Nature. 1980;283(5747):545–9. 10.1038/283545a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Unwin PN, Ennis PD: Two configurations of a channel-forming membrane protein. Nature. 1984;307(5952):609–13. 10.1038/307609a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paul DL: Molecular cloning of cDNA for rat liver gap junction protein. J Cell Biol. 1986;103(1):123–34. 10.1083/jcb.103.1.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar NM, Gilula NB: Cloning and characterization of human and rat liver cDNAs coding for a gap junction protein. J Cell Biol. 1986;103(3):767–76. 10.1083/jcb.103.3.767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA: Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(6 Pt 1):2621–9. 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang JT, Nicholson BJ: Sequence and tissue distribution of a second protein of hepatic gap junctions, Cx26, as deduced from its cDNA. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(6 Pt 2):3391–401. 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodenough DA, Paul DL, Jesaitis L: Topological distribution of two connexin32 antigenic sites in intact and split rodent hepatocyte gap junctions. J Cell Biol. 1988;107(5):1817–24. 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yancey SB, John SA, Lal R, et al. : The 43-kD polypeptide of heart gap junctions: immunolocalization, topology, and functional domains. J Cell Biol. 1989;108(6):2241–54. 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, et al. : Three-dimensional structure of a recombinant gap junction membrane channel. Science. 1999;283(5405):1176–80. 10.1126/science.283.5405.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Purnick PE, Benjamin DC, Verselis VK, et al. : Structure of the amino terminus of a gap junction protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381(2):181–90. 10.1006/abbi.2000.1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kyle JW, Berthoud VM, Kurutz J, et al. : The N terminus of connexin37 contains an α-helix that is required for channel function. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):20418–27. 10.1074/jbc.M109.016907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shao Q, Liu Q, Lorentz R, et al. : Structure and functional studies of N-terminal Cx43 mutants linked to oculodentodigital dysplasia. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(17):3312–21. 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 21. Maeda S, Nakagawa S, Suga M, et al. : Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 Å resolution. Nature. 2009;458(7238):597–602. 10.1038/nature07869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 22. Bennett BC, Purdy MD, Baker KA, et al. : An electrostatic mechanism for Ca 2+-mediated regulation of gap junction channels. Nat Commun. 2016;7:8770. 10.1038/ncomms9770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 23. Kwon T, Harris AL, Rossi A, et al. : Molecular dynamics simulations of the Cx26 hemichannel: Evaluation of structural models with Brownian dynamics. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138(5):475–93. 10.1085/jgp.201110679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 24. Locke D, Bian S, Li H, et al. : Post-translational modifications of connexin26 revealed by mass spectrometry. Biochem J. 2009;424(3):385–98. 10.1042/BJ20091140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zonta F, Polles G, Zanotti G, et al. : Permeation pathway of homomeric connexin 26 and connexin 30 channels investigated by molecular dynamics. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2012;29(3):985–98. 10.1080/073911012010525027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakagawa S, Maeda S, Tsukihara T: Structural and functional studies of gap junction channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(4):423–30. 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suchyna TM, Nitsche JM, Chilton M, et al. : Different ionic selectivities for connexins 26 and 32 produce rectifying gap junction channels. Biophys J. 1999;77(6):2968–87. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77129-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Veenstra RD: Size and selectivity of gap junction channels formed from different connexins. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1996;28(4):327–37. 10.1007/BF02110109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cao F, Eckert R, Elfgang C, et al. : A quantitative analysis of connexin-specific permeability differences of gap junctions expressed in HeLa transfectants and Xenopus oocytes. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 1):31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valiunas V, Beyer EC, Brink PR: Cardiac gap junction channels show quantitative differences in selectivity. Circ Res. 2002;91(2):104–11. 10.1161/01.RES.0000025638.24255.AA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Musa H, Fenn E, Crye M, et al. : Amino terminal glutamate residues confer spermine sensitivity and affect voltage gating and channel conductance of rat connexin40 gap junctions. J Physiol (Lond). 2004;557(Pt 3):863–78. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gemel J, Lin X, Veenstra RD, et al. : N-terminal residues in Cx43 and Cx40 determine physiological properties of gap junction channels, but do not influence heteromeric assembly with each other or with Cx26. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 11):2258–68. 10.1242/jcs.02953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dong L, Liu X, Li H, et al. : Role of the N-terminus in permeability of chicken connexin45.6 gap junctional channels. J Physiol (Lond). 2006;576(Pt 3):787–99. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kyle JW, Minogue PJ, Thomas BC, et al. : An intact connexin N-terminus is required for function but not gap junction formation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 16):2744–50. 10.1242/jcs.032482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oh S, Verselis VK, Bargiello TA: Charges dispersed over the permeation pathway determine the charge selectivity and conductance of a Cx32 chimeric hemichannel. J Physiol (Lond). 2008;586(10):2445–61. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xin L, Gong X, Bai D: The role of amino terminus of mouse Cx50 in determining transjunctional voltage-dependent gating and unitary conductance. Biophys J. 2010;99(7):2077–86. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xin L, Nakagawa S, Tsukihara T, et al. : Aspartic acid residue D3 critically determines Cx50 gap junction channel transjunctional voltage-dependent gating and unitary conductance. Biophys J. 2012;102(5):1022–31. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schlingmann B, Schadzek P, Busko S, et al. : Cataract-associated D3Y mutation of human connexin46 (hCx46) increases the dye coupling of gap junction channels and suppresses the voltage sensitivity of hemichannels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012;44(5):607–14. 10.1007/s10863-012-9461-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tong JJ, Sohn BCH, Lam A, et al. : Properties of two cataract-associated mutations located in the NH 2 terminus of connexin 46. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304(9):C823–32. 10.1152/ajpcell.00344.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trexler EB, Bukauskas FF, Kronengold J, et al. : The first extracellular loop domain is a major determinant of charge selectivity in connexin46 channels. Biophys J. 2000;79(6):3036–51. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76539-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kronengold J, Trexler EB, Bukauskas FF, et al. : Single-channel SCAM identifies pore-lining residues in the first extracellular loop and first transmembrane domains of Cx46 hemichannels. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122(4):389–405. 10.1085/jgp.200308861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tong JJ, Minogue PJ, Guo W, et al. : Different consequences of cataract-associated mutations at adjacent positions in the first extracellular boundary of connexin50. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300(5):C1055–64. 10.1152/ajpcell.00384.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanchez HA, Villone K, Srinivas M, et al. : The D50N mutation and syndromic deafness: altered Cx26 hemichannel properties caused by effects on the pore and intersubunit interactions. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142(1):3–22. 10.1085/jgp.201310962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tong X, Aoyama H, Tsukihara T, et al. : Charge at the 46th residue of connexin 50 is crucial for the gap-junctional unitary conductance and transjunctional voltage-dependent gating. J Physiol (Lond). 2014;592(23):5187–202. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.280636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tong X, Aoyama H, Sudhakar S, et al. : The First Extracellular Domain Plays an Important Role in Unitary Channel Conductance of Cx50 Gap Junction Channels. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143876. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luo Y, Rossi AR, Harris AL: Computational studies of molecular permeation through connexin26 channels. Biophys J. 2016;110(3):584–99. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.3528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Araya-Secchi R, Perez-Acle T, Kang S, et al. : Characterization of a novel water pocket inside the human Cx26 hemichannel structure. Biophys J. 2014;107(3):599–612. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brennan MJ, Karcz J, Vaughn NR, et al. : Tryptophan scanning reveals dense packing of connexin transmembrane domains in gap junction channels composed of connexin32. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(28):17074–84. 10.1074/jbc.M115.650747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Foote CI, Zhou L, Zhu X, et al. : The pattern of disulfide linkages in the extracellular loop regions of connexin 32 suggests a model for the docking interface of gap junctions. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(5):1187–97. 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schadzek P, Schlingmann B, Schaarschmidt F, et al. : The cataract related mutation N188T in human connexin46 (hCx46) revealed a critical role for residue N188 in the docking process of gap junction channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1858(1):57–66. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gong XQ, Nakagawa S, Tsukihara T, et al. : A mechanism of gap junction docking revealed by functional rescue of a human-disease-linked connexin mutant. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 14):3113–20. 10.1242/jcs.123430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Koval M, Molina SA, Burt JM: Mix and match: investigating heteromeric and heterotypic gap junction channels in model systems and native tissues. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(8):1193–204. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. White TW, Bruzzone R, Wolfram S, et al. : Selective interactions among the multiple connexin proteins expressed in the vertebrate lens: the second extracellular domain is a determinant of compatibility between connexins. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(4):879–92. 10.1083/jcb.125.4.879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. White TW, Paul DL, Goodenough DA, et al. : Functional analysis of selective interactions among rodent connexins. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6(4):459–70. 10.1091/mbc.6.4.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Oh S, Abrams CK, Verselis VK, et al. : Stoichiometry of transjunctional voltage-gating polarity reversal by a negative charge substitution in the amino terminus of a connexin32 chimera. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116(1):13–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kwon T, Roux B, Jo S, et al. : Molecular dynamics simulations of the Cx26 hemichannel: insights into voltage-dependent loop-gating. Biophys J. 2012;102(6):1341–51. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Snipas M, Kraujalis T, Paulauskas N, et al. : Stochastic Model of Gap Junctions Exhibiting Rectification and Multiple Closed States of Slow Gates. Biophys J. 2016;110(6):1322–33. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 58. Sanchez HA, Bienkowski R, Slavi N, et al. : Altered inhibition of Cx26 hemichannels by pH and Zn 2+ in the A40V mutation associated with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(31):21519–32. 10.1074/jbc.M114.578757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Sanchez HA, Slavi N, Srinivas M, et al. : Syndromic deafness mutations at Asn 14 differentially alter the open stability of Cx26 hemichannels. J Gen Physiol. 2016;148(1):25–42. 10.1085/jgp.201611585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Oshima A, Tani K, Toloue MM, et al. : Asymmetric configurations and N-terminal rearrangements in connexin26 gap junction channels. J Mol Biol. 2011;405(3):724–35. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Purnick PE, Oh S, Abrams CK, et al. : Reversal of the gating polarity of gap junctions by negative charge substitutions in the N-terminus of connexin 32. Biophys J. 2000;79(5):2403–15. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76485-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oh S, Rivkin S, Tang Q, et al. : Determinants of gating polarity of a connexin 32 hemichannel. Biophys J. 2004;87(2):912–28. 10.1529/biophysj.103.038448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Verselis VK, Trelles MP, Rubinos C, et al. : Loop gating of connexin hemichannels involves movement of pore-lining residues in the first extracellular loop domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(7):4484–93. 10.1074/jbc.M807430200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tang Q, Dowd TL, Verselis VK, et al. : Conformational changes in a pore-forming region underlie voltage-dependent “loop gating” of an unapposed connexin hemichannel. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133(6):555–70. 10.1085/jgp.200910207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu S, Taffet S, Stoner L, et al. : A structural basis for the unequal sensitivity of the major cardiac and liver gap junctions to intracellular acidification: the carboxyl tail length. Biophys J. 1993;64(5):1422–33. 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81508-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ek-Vitorin JF, Calero G, Morley GE, et al. : pH regulation of connexin43: molecular analysis of the gating particle. Biophys J. 1996;71(3):1273–84. 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79328-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Morley GE, Taffet SM, Delmar M: Intramolecular interactions mediate pH regulation of connexin43 channels. Biophys J. 1996;70(3):1294–302. 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79686-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stergiopoulos K, Alvarado JL, Mastroianni M, et al. : Hetero-domain interactions as a mechanism for the regulation of connexin channels. Circ Res. 1999;84(10):1144–55. 10.1161/01.RES.84.10.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Duffy HS, Sorgen PL, Girvin ME, et al. : pH-dependent intramolecular binding and structure involving Cx43 cytoplasmic domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):36706–14. 10.1074/jbc.M207016200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Locke D, Kieken F, Tao L, et al. : Mechanism for modulation of gating of connexin26-containing channels by taurine. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138(3):321–39. 10.1085/jgp.201110634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zonta F, Mammano F, Torsello M, et al. : Role of gamma carboxylated Glu47 in connexin 26 hemichannel regulation by extracellular Ca 2+: insight from a local quantum chemistry study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445(1):10–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lee JR, DeRosa AM, White TW: Connexin mutations causing skin disease and deafness increase hemichannel activity and cell death when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(4):870–8. 10.1038/jid.2008.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lopez W, Gonzalez J, Liu Y, et al. : Insights on the mechanisms of Ca 2+ regulation of connexin26 hemichannels revealed by human pathogenic mutations (D50N/Y). J Gen Physiol. 2013;142(1):23–35. 10.1085/jgp.201210893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lopez W, Liu Y, Harris AL, et al. : Divalent regulation and intersubunit interactions of human connexin26 (Cx26) hemichannels. Channels (Austin). 2014;8(1):1–4. 10.4161/chan.26789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lopez W, Ramachandran J, Alsamarah A, et al. : Mechanism of gating by calcium in connexin hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(49):E7986–E7995. 10.1073/pnas.1609378113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 76. Pfahnl A, Dahl G: Localization of a voltage gate in connexin46 gap junction hemichannels. Biophys J. 1998;75(5):2323–31. 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77676-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gómez-Hernández JM, de Miguel M, Larrosa B, et al. : Molecular basis of calcium regulation in connexin-32 hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(26):16030–5. 10.1073/pnas.2530348100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 78. Peracchia C, Sotkis A, Wang XG, et al. : Calmodulin directly gates gap junction channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(34):26220–4. 10.1074/jbc.M004007200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Puljung MC, Berthoud VM, Beyer EC, et al. : Polyvalent cations constitute the voltage gating particle in human connexin37 hemichannels. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124(5):587–603. 10.1085/jgp.200409023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dodd R, Peracchia C, Stolady D, et al. : Calmodulin association with connexin32-derived peptides suggests trans-domain interaction in chemical gating of gap junction channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(40):26911–20. 10.1074/jbc.M801434200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Xu Q, Kopp RF, Chen Y, et al. : Gating of connexin 43 gap junctions by a cytoplasmic loop calmodulin binding domain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302(10):C1548–56. 10.1152/ajpcell.00319.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen Y, Zhou Y, Lin X, et al. : Molecular interaction and functional regulation of connexin50 gap junctions by calmodulin. Biochem J. 2011;435(3):711–22. 10.1042/BJ20101726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sorgen PL, Duffy HS, Sahoo P, et al. : Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein connexin43 indicates signaling between binding domains for c-Src and zonula occludens-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54695–701. 10.1074/jbc.M409552200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Spagnol G, Al-Mugotir M, Kopanic JL, et al. : Secondary structural analysis of the carboxyl-terminal domain from different connexin isoforms. Biopolymers. 2016;105(3):143–62. 10.1002/bip.22762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Toyofuku T, Yabuki M, Otsu K, et al. : Intercellular calcium signaling via gap junction in connexin-43-transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(3):1519–28. 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mondal A, Appadurai DA, Akoum NW, et al. : Computational simulations of asymmetric fluxes of large molecules through gap junction channel pores. J Theor Biol. 2017;412:61–73. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]