Abstract

In recent years, several OECD countries have taken steps to promote policies encouraging fathers to spend more time caring for young children, thereby promoting a more gender equal division of care work. Evidence, mainly for the United States and United Kingdom, has shown fathers taking some time off work around childbirth are more likely to be involved in childcare related activities than fathers who do not take time off. This paper conducts a first cross-national analysis on the association between fathers’ leave taking and fathers’ involvement when children are young. It uses birth cohort data of children born around 2000 from four OECD countries: Australia, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the United States. Results show that the majority of fathers take time off around childbirth independent of the leave policies in place. In all countries, except Denmark, important socio-economic differences between fathers who take leave and those who do not are observed. In addition, fathers who take leave, especially those taking two weeks or more, are more likely to carry out childcare related activities when children are young. This study adds to the evidence that suggests that parental leave for fathers is positively associated with subsequent paternal involvement.

Keywords: parental leave, paternal involvement, childcare, early years, child development, birth cohort studies, Australia, Denmark, the United Kingdom, the United States

1. Introduction

Fathers of the twenty-first century are more involved in children’s lives than before (Gauthier et al., 2004; Hook, 2006; Maume, 2011; O’Brien et al., 2007; and, United Nations, 2011). Although the timing and pace of change varies widely across countries, a change in the role of fathers is observed worldwide (O’Brien et al., 2007). Men are no longer expected to be exclusive breadwinners but are frequently expected to share the caring responsibilities with their partners. However, despite important progress, women still are the main caregivers. This is true even in the Scandinavian countries, who are the pioneers in supporting gender equality in the division of work inside and outside the household (Rostgaard, 2002 and Miranda, 2011).

Numerous factors have contributed to men’s increased participation in housework and care activities, including: growing female employment; increased family diversity; changes in attitudes towards work and care; and, availability of family-friendly policies. However, it is argued that the main determinant for men’s increased involvement is women’s greater participation in paid work and their contribution to households’ earnings (O’Brien and Moss, 2010 and Maume, 2011). Today in most OECD countries the majority of couple families are dual earners (OECD, 2011). Thus, both mothers and fathers have had to find a new balance between work and family responsibilities.

Family-friendly policies to help parents find their preferred balance between parenting and employment have been introduced in many OECD countries (OECD, 2011). Furthermore, in recent years, there has been increasing interest in developing policies to support fathers in contributing more to caring for young children. The underlying objectives behind these policies may differ across countries, but, in general, they aim to increase gender equality at home and at the workplace as well as to strengthen father-child relationships and thus improve child well-being outcomes (Rostgaard, 2002).

Available evidence shows fathers want to spend time caring for and being with their children as in many countries an overwhelming proportion of fathers takes time off work around childbirth (Moss, 2011 and O’Brien et al., 2007). What is more, in countries without legal parental leave provisions in place, fathers use other types of leave to spend time with their children during the first months of life (La Valle et al., 2008; and, Whitehouse et al., 2007). However, the amount of time fathers take off is greatly influenced by their leave entitlements.

Parental leave policies are relevant for influencing parental behaviour as they intervene at a critical point in the life-course; that is, around childbirth (Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007 and Dex, 2010). At this critical point, parents, especially fathers, may be more open to changing behaviours. For example, parental leave may facilitate fathers sharing childcare-related tasks with their partners. Sharing these activities during a child’s first year of life may promote less stereotyped gender roles; that is, mother as exclusive caregiver and father as exclusive breadwinner. Moreover, taking care of children from the early days may facilitate father-child bonding (Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007). Early paternal involvement may lead to continued engagement and involvement in children’s lives and to a more equal division of work between parents (Baxter and Smart, 2011 and Brandth and Gislason, 2012 O’Brien and Moss, 2010; Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007; and, Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007).

Positive father involvement, in turn, is associated with numerous benefits, including better outcomes for children (Baxter and Smart, 2011; Cabrera et al., 2007; Lamb, 2010; OECD, 2012a; Sarkadi et al., 2008; and, WHO, 2007), for fathers themselves (Baxter and Smart, 2011; Eggebeen, 2001; Smith, 2011; and, WHO, 2007), and for the family as a whole. For instance, fathers who spend more time with their children have, on average, more favourable labour market outcomes – earn more per hour and work fewer hours per week – than their peers who spend less time with their children (Smith, 2011); fathers who contribute more to housework and childcare experience a lower risk of divorce than fathers who contribute less (Sigle-Rushton, 2010); and, fathers who are more engaged with their children are more satisfied with their lives than their counterparts who engage less (Eggebeen, 2001).

The aim of this study is to examine whether taking leave around the time of birth (paternity leave, parental leave or annual leave) is associated with father’s involvement in childcare-related activities in four OECD countries with different leave entitlements for fathers. Fathers’ involvement in childcare has beneficial effects for children and parents, and raises a need for policy makers to invest in policies that encourage men to be more involved in childrearing tasks. Encouraging fathers to make better use of parental leave arrangements can contribute to changing attitudes and behaviours towards the role of fathers and mothers in childcare and in labour force participation. Identifying the proportion of fathers that take time off work to be with their new-borns, their characteristics and their level of involvement across different countries also helps informing policymakers on the efforts needed to extend fathers’ use of parental leave.

This paper follows previous work by Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel (2007), for the United States. It presents for the first time a comparative analysis of birth cohort data of four OECD countries: Australia, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the United States. One of the advantages of conducting a cross-national analysis is to identify and explain similarities and differences between countries. These countries were selected because they have collected national longitudinal data on fathers’ leave and childcare-related tasks from the time around birth. On basis of this study alone, which covers just four countries, it is not possible to state that all countries should invest in paternity leave. However, the results from this analysis can contribute to further development and promotion of parental-leave policies for the exclusive use of fathers.

The next section sets the background of this research by presenting a picture of fathers’ involvement and an overview of relevant family policies in OECD countries. The third section provides information on the data, the variables and the methodology used in the analysis. The fourth section describes the results; and the final section provides a discussion of the key findings of the study and concludes.

2. Background and literature

An important barrier to paternal involvement in children’s lives is the time fathers dedicate to other activities, especially the time they spend at work. Fatherhood may put some pressure on fathers’ working behaviours as they tend to be the main household earner. However, “earning” seems to have become more compatible with “caring”. Across all countries for which time-use data are available, father’s time as caregivers has increased compared with previous generations. For example, Hook (2006) estimates that, in 2003, resident fathers in industrialised countries spent on average 6 more hours per week in unpaid work (i.e., childcare and housework activities) than fathers in 1965. Likewise, Gauthier et al. (2004) and Bianchi et al. (2006) show that married fathers in 2000 spent more time in childcare activities than fathers in the 1960s (48 minutes per day more, Gauthier et al., 2004). Recent estimates from France also show an upward trend between 1999 and 2010 (Ricroch, 2012).

The parental gap in caring, however, seems to be narrowing during weekends only. Studies distinguishing time use between workdays and weekends have observed that fathers’ time in childcare tasks has increased mainly on weekends (Maume, 2011 and Yeung et al., 2001), when fathers’ availability to contribute to childcare is less constrained by their time in paid work. Evidence from the United States shows that most mothers remain the main caregiver during weekdays, but that during the weekends there is a more equal sharing of care responsibilities between parents (Yeung et al., 2001). This is apparent for Australia also, when examining children’s co-presence with mothers and fathers on weekends and weekdays in couple households (Baxter, 2009).

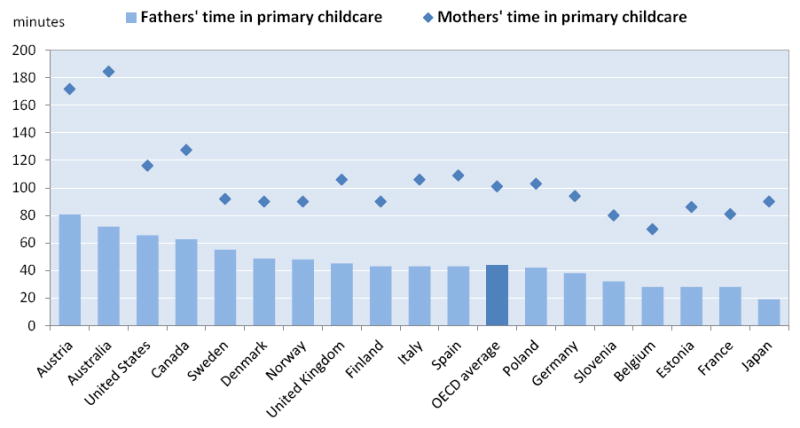

Figure 1 presents the amount of time devoted to childcare by mothers and fathers with children under the age of 18 across the 18 OECD countries for which data are available. These statistics clearly show the total amount of time devoted to childcare as a primary activity differs significantly between mothers and fathers. Fathers spent on average a total of 42 minutes per day on childcare, while mothers devoted an average of 1 hour and 40 minutes a day. Across all countries, fathers spent less than half as much time on childcare as mothers did. The total amount of time devoted to children also differs considerably across countries. Father’s total time invested in childcare was highest in Australia, Austria, Canada and the United States - with more than 1 hour a day; and lowest in Belgium, Estonia, France, Japan and South Africa - with less than 30 minutes a day.

Figure 1. Across all countries, fathers spend less time in childcare than mothers do.

Primary childcare in minutes per day for parents aged 15-64, disaggregated by sex, over the period 1998-2010

Note: Countries are ranked in ascending order of the minutes per day fathers spend in primary childcare. The definition of “parents” is based on resident children.

Source: OECD (2012b).

The degree of parental involvement is influenced by numerous factors including fathers’ socio-economic characteristics, children’s age, attitudes towards work and care, social expectations, workplace culture and the availability of family-friendly policies. In the Nordic countries, where work-family policies have been operating for over 40 years, views towards work and care are more gender equal. Hence, it is easier for Nordic fathers to make use of their leave entitlements and to spend more time caring for children than for their peers in countries with traditional views on work and care commitments and with less developed family-friendly policies.

Likewise, fathers’ participation in childcare may be greatly influenced by socio-economic characteristics. Education, for instance, is likely to be related with fathers’ involvement, but the direction of this association it is not clear. For instance, Yeung et al. (2001) found that better educated fathers are more likely to spend more time with children as they tend to be more concerned about their children’s development than less educated fathers. At the same time, better educated fathers are more likely to have jobs with more family-friendly work arrangements than less educated fathers so it is easier for them to take time off work when children are born. However, fathers with better education and better jobs may be more reluctant to take leave as this may be perceived as damaging their careers. Hence, it is important to control for fathers’ education to avoid overestimating or underestimating the association between leave and involvement.

Other characteristics of the father that may affect their involvement include age, marital status, ethnicity, the number of hours at work, occupation and attitudes towards care and work. Some studies have found older fathers spend less time with their children (Maume, 2011), but others have found that, depending on the measure used, fathers’ involvement either does not vary with age, or is sometimes greater for older fathers (Baxter and Smart, 2011). Younger fathers may have higher energy levels and less gender stereo-typed attitudes towards care than older fathers, making it easier to engage in childcare activities. On the other hand, younger fathers may be starting their careers and hence therefore have less flexibility in “managing” their time with children than older fathers. The father’s marital status may reflect father’s commitment to the relationship (Wiik et al., 2009), which in turn may facilitate a more equal share of childcare and other responsibilities. Baxter and Smart (2011) found, however, that difference in fathering between cohabiting fathers and married fathers tend to be small. Attitudes towards fathers’ involvement in child-related tasks may also differ according to ethnicity, but such effects could be expected to differ also across countries. For example, in the United States, Yeung et al. (2001) observed that Black fathers are less involved than Latino fathers, but only during the weekends. Baxter and Smart (2011) found quite small differences according to fathers’ ethnicity in Australia. Finally, fathers’ working practices may negatively affect paternal involvement, especially when working long hours.

A number of mother’s characteristics are likely to influence father’s involvement in care giving. Better-educated mothers tend to be more knowledgeable of children’s development and needs and may demand that partners spend time with their children. Mother’s employment is positively associated with paternal involvement: the more time mothers spend in the labour market and the more they contribute to the family income, the more involved fathers will be (Baxter and Smart, 2011 and Yeung et al., 2001). Mothers’ mental health is likely to influence the amount of time fathers spend with their children. The direction of the association is, however, not clear: fathers with a depressed partner may spend more time in primary care activities to compensate for mothers lack of involvement, but on the other hand maternal depression may lead to high conflict between partners which, in turn, may pose disincentives for paternal involvement. In addition, mothers’ poorer mental health may also reflect poorer family relationships and so may actually be an outcome of fathers being less engaged in the family.

Father’s involvement is likely to vary according to child’s characteristics. For example, the literature shows that the age of the child is an important determinant of the time parents devote to childcare activities (Baxter and Smart, 20011; Lamb, 2010; and, Yeung et al., 2011). Fathers’ childcare time seems to reach a peak level at pre-school age and then rapidly declines with increasing age of the child (Baxter and Smart, 2011 and Maume, 2011). Temperament is another characteristic of the child that may influence parental involvement. Parents may find it difficult to engage in activities with children with difficult temperament (Baxter and Smart, 2011 and Lamb, 2010). It appears, however, that the relationship between child’s temperament and parental involvement is stronger for fathers than for mothers (McBride et al., 2002). The sex of the child may also affect how fathers interact with their children. Although there is no conclusive evidence on whether fathers are more involved with boys or girls, it is possible that for certain tasks fathers engage differently with sons and daughters (Lamb, 2010). For example, Baxter (2012) found that fathers are somewhat more involved with sons than with daughters in the more personal of the care activities, such as helping children with the toilet and with bathing or showering. The number of children in the household may also affect the amount of time fathers spend in childcare-related tasks. Fathers dedicate less time to their children when they are in large families, perhaps in part because additional time is spent on other domestic work in these families (Baxter and Smart, 2011).

Finally, fathers’ involvement in children’s lives may be driven by fathers’ commitment to taking care of their children. Some fathers may be more committed to taking care of their children than others, seeking opportunities for actively engaging with children. For example, fathers who are committed to partner and baby before he/she is born – for instance, those married, or attending pre-birth classes or present at delivery - are possibly those who take longer periods of leave or who are entitled to paternity or parental leave.

Parental leave provision for fathers across the OECD

Many OECD countries have introduced family-friendly working arrangements to help parents reduce some of the barriers that make it difficult for them to spend more time with their children. These family-friendly arrangements include leave from work around childbirth and/or when children are young, as well as support with childcare and out-of-school care services, and flexibility to adjust working practices (OECD, 2011). Moreover, in the last two decades, several OECD governments have taken steps to further promote policies encouraging fathers to spend more time caring for children and promote a more gender equal division of care work. As Table 1 shows, these policies are not limited to the countries here selected.

Table 1.

Paternity and parental leave schemes across the OECD, 2011

| Paternity leave1 | % rate of allowance2 | FRE paid paternity leave | Year of introduction - paternity leave (or parental leave for fathers) | Parental leave3 | Characteristics of parental leave | Incentives for fathers to take leave | Transferring part of maternity leave to fathers without exceptional circumstances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Father’s quota | Bonus | ||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (7) | (8) | |

| Australia4 | .. | .. | .. | 2013 | 52 weeks per parent - unpaid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| Austria | .. | .. | .. | 1990 (parental leave) | Parents can choose between 5 payment and duration options until child reaches age 2 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | Bonus - in the 5 different schemes there are paid ‘partner’ months for the exclusive use of the other parent | .. |

| Belgium | 2 weeks (three days obligatory) | 87.4 | 1.2 | 1961 | 16 weeks per parent | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| Canada (Quebec) | 3 to 5 weeks | 75 or 70 | .. | 2006 | 35 weeks | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Chile | 1.0 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 2005 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Czech Republic | .. | .. | .. | 2001 (parental leave – employment protected for fathers) | 156 weeks per parent until child reaches age 3 | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | yes |

| Denmark | 2.0 | 55.0 | 1.1 | 1984 | 32 weeks | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose, but the total leave period cannot exceed more than 32 weeks per family | 3 weeks (only in industrial sector) | .. | .. |

| Estonia | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2008 | 156 weeks per parent until child reaches age 3 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Finland | 3+4 bonus weeks | 70.0 | 4.9 | 1991 | 26.5 weeks | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | 4 ‘bonus weeks’ if father takes at least 2 weeks of parental leave | .. |

| France | 2.0 | 100.0 | 2.0 | 2002 | 156 weeks per parent until child reaches age 3 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Germany5 | 8.0 | 67.4 | 5.4 | 2007 | 156 weeks per parent until child reaches age 3 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | Overall length of benefit payment is extended to 14 months if father takes at least 2 months of leave | .. |

| Greece | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 2000 | 14 weeks per parent - unpaid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| Hungary | 1.0 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 2002 | 156 weeks per parent until child reaches age 3 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Iceland | 13.0 | 64.6 | 8.4 | 1998 | 13 weeks per parent | Mixed entitlement, a total leave of 9 months (including maternity, paternity and parental leave) can be used | 13 weeks | .. | .. |

| Ireland | .. | .. | .. | .. | 14 weeks per parent - unpaid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| Italy | .. | .. | .. | .. | 26 weeks per parent | Individual entitlement, w ith total amount of leave not exceeding 10 months | .. | 1 month bonus if father takes at least 3 months of leave | .. |

| Japan | .. | .. | .. | 2010 –introduction of bonus | 52 weeks + 8 weeks ‘sharing bonus’ | Individual entitlement | .. | 2 month bonus if parents share leave | .. |

| Korea | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 2008 | 45.6 weeks | Individual entitlement, but parents cannot take leave at the same time | .. | .. | .. |

| Luxembourg | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 1962 | 26 weeks per parent - paid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| Mexico | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Netherlands | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 2001 | 26 weeks per parent until child is 8 | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | .. |

| New Zealand | 1 or 2 depending on eligibility | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1987 - extension of parental leave to fathers | 52 weeks including maternity and paternity leave | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Norway | 2 + 12 fathers’ quota | 85.7 | 12.0 | 1993 | 27 or 37 weeks depending on payment level | Mixed entitlement, part family part individual | 12 weeks | .. | .. |

| Poland | 2.0 | 100.0 | 2.0 | 1996 | 156 weeks until child reaches age 4 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | yes |

| Portugal | 4 weeks (10 days obligatory) | 100.0 | 4.0 | 1995 | 12 weeks to be shared | Mixed entitlement, part family part individual | .. | 1 month bonus if parents share intial leave and father takes 2 weeks of paternity leave (the latter compulsory) | .. |

| Slovak Republic | .. | .. | .. | .. | 136.0 | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Slovenia | 13.0 | 26.9 | 3.5 | 2003 | 37 weeks | Family entitlement to be divided between parents as they choose | .. | .. | .. |

| Spain | 3.0 | 100.0 | 3.0 | 2007 | 156 weeks per parent - unpaid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | yes |

| Sweden | 10.0 | 80.0 | 8.0 | 1980 | 68.6 weeks in total: 8.5 weeks reserved for each parent and 51.6 to be split into half (the latter can be transferred between parents) | Mixed entitlement, part family part individual | 8.5 weeks | Gender equality bonus: parents receive €5.6 each per day for every day they use the leave equally | .. |

| Switzerland | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Turkey | .. | .. | .. | .. | 26.0 | .. | .. | .. | |

| United Kingdom | 2.0 | 20.0 | 0.4 | 2003 | 13 weeks per parent - unpaid | Individual entitlement | .. | .. | yes |

| United States6 | .. | .. | .. | 1993 | 12 weeks unpaid | .. | .. | .. | .. |

Information refers to the entitlement for paternity leave in a strict sense and the bonus (for example, Germany) or father quota included in some parental leave regulations (for example, Finland, Iceland and Norway). In Finland,

The “rate of allowance” is defined as the ratio between the full-time equivalent payment and the corresponding entitlement in number of weeks.

Information refers to parental leave and subsequent prolonged periods of paid leave to care for young children (sometimes under a different name as for example, “childcare leave” or “Home care leave”, or the Complément de Libre Choix d’Activité in France). In all, prolonged periods of leave can be taken in Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Finland, Germany, Norway, Poland and Spain.

In Australia, the introduction of two weeks paid paternity leave will take place from 1 January 2013.

This 8 weeks correpond to the bonus given if fathers make use of 2 months of parental leave.

Through the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), entitled eligible employees may take up to 12 weeks of unpaid, employment-protected leave in a 12-month period for specific family and medical reasons. Although the table presents federal statutory entitlements, the United States also has parental leave schemes at the state level. Ten states plus the District of Columbia have laws that give some male workers employment-protected paternity leave. The length of leave varies between 4 and 18 weeks.

Source: Moss (2012) and OECD (2012b) - indicator PF2.5

There are two kinds of leave entitlements fathers may have access to: paternity leave and/or parental leave. Paternity leave is a father-specific right to take some time off work soon after the birth of a child. In general, these entitlements are of short duration, except in Germany, Iceland, Slovenia and Sweden. Belgium and Luxembourg were the first countries to introduce paternity leave entitlement in the 1960s (Table 1). Today, about two-thirds of OECD countries provide paternity leave entitlements. Parental leave is a form of leave that either parent can take. The parental leave period generally follows the period of maternity or paternity leave and is often supplementary to maternity and paternity leave periods. Sweden was the first country to introduce parental leave for both parents in 1974 (Brandth and Gislason, 2012). Twenty years later other countries started extending parental-leave entitlements to fathers (O’Brien, 2009). Today most OECD countries award fathers the right to use some of the parental-leave period (Table 1).

Some OECD countries have introduced additional measures to motivate fathers to make use of their leave entitlements: father’s “quotas” and “bonus”. “Quotas” were introduced in 1993 in Norway (O’Brien et al., 2007) with the aim of reserving some part of the parental-leave period for the exclusive use of fathers. The entitlement cannot be passed to the mother: if it is not used, it is lost. Currently, only the Nordic countries have a “quota” system, with Iceland having the largest quota (3 month quota for each parent and 3 months to share4). On the other hand, several countries (Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Sweden) provide a “bonus” to the total period of parental leave if fathers take at least some part of the parental-leave period.

Overall, there are important cross-country differences in the design, duration and generosity of child-related leave policies. Taking into account paternity leave and parental leave for the use of fathers, the countries with the most generous leave models, in terms of duration and income replacement, are the Nordic countries (except Denmark), Germany, Portugal and Slovenia (O’Brien, 2009). At the other end of the spectrum, Mexico, Turkey and the United States have no statutory paid leave entitlements for fathers.

In the early 2000s, at the time children in the cohort studies here analysed were born, only Denmark provided paid parental-leave entitlements to fathers with two weeks of paid-leave in connection with childbirth. In the United Kingdom, a two-week paid paternity statutory leave was introduced in 2003. In Australia, a two week paid paternity leave provision was introduced on January 2013. In the United States, however, to date no statutory leave entitlements for fathers (or mothers) are available. Fathers working in medium or large firms may take 12 weeks of unpaid, employment-protected leave through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), while other workers may be covered by state or employer policies. Today, ten states plus the District of Columbia have laws that give at least some male workers employment-protected paternity leave.

Despite increased availability of statutory leave entitlements for fathers in many countries, use remains low. Mothers rather than fathers continue to make use of leave entitlements since income loss is usually smallest when mothers take leave (OECD, 2012c). Fathers’ take-up rates are low and the period they stay at home is short when payments are low; when parents can share the entitlement as they choose (family right); and/or when the entitlement is transferable to the other parent (transferable individual right). For example, in Austria, the Czech Republic and Poland, where leave entitlements are fully transferrable, the proportion of fathers taking parental leave is less than 3 % (Moss, 2011).

Alternatively, fathers’ use of paternity and parental leave is largest when leave is well-paid and when part of the entitlement cannot be transferred, and is lost if not used (O’Brien and Moss, 2010). Countries with parental-leave policies that have been successful in encouraging fathers to take leave meet these criteria. These include Sweden, Iceland and Norway, where around 90% of fathers take some part of the parental leave period (Moss, 2011). Moreover, in these countries a considerable number of fathers stay at home for a relatively long period. For example, in Norway, 70 % of eligible fathers took more than five weeks of leave in 2006, after the extension of the father’s quota to six weeks (Moss, 2011).

Available evidence shows paternity leave does influence father’s involvement in childcare activities. A Swedish study shows fathers who take more leave than average are more involved in childcare-related tasks and household work than fathers taking shorter periods of leave (Haas and Hwang, 2008). Evidence from the United Kingdom and United States suggests that, in spite of having no formal leave entitlements, fathers who take leave after childbirth are significantly more involved in childcare activities than fathers who do not take time off work (Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007). Nevertheless, in the United States, this positive association was observed only when fathers took periods of leave of two or more weeks (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007). These results are, however, not universal. For Australia, Hosking et al. (2010) observed the amount of time fathers spent with their infants was no different for those who had taken 4 or more weeks of leave after the birth compared with those who had taken less than 4 weeks of leave or no leave.

3. Data and methods

This study uses information from four OECD countries which have gathered longitudinal data on birth cohorts and which share similar methods of data collection. The main criteria used for considering inclusion in this study were: 1) comparable information on fathers’ use of leave around childbirth; and fathers’ involvement with young children; 2) cohort members being born around same time; 3) children being monitored during early childhood; 4) nationally representative sample. The cohort studies included were:

Australia: Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. The analysis here uses data of the B-cohort, children who were born between March 2003 and February 2004. The sample size of this cohort at wave 1 was 5 107 and children were aged between 3 and 14 months. The first two waves of the study have been used here: 1) in 2004, when children were aged 0 to 1; and 2) in 2006, when children were aged 2 to 3.

Denmark: Danish Longitudinal Survey of Children (DALSC). This is a representative sample of Danish children born within 6 weeks in the fall of 1995. The sample size of DALSC is around 6 000 children. One wave of the study was used here: 1) in 1996, when babies were about 6 months old.

United Kingdom: Millennium Cohort Study (MCS). This is a multi-disciplinary survey of around 19 000 children born in the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom in 2000-01. The first two waves of data collection have been used here: 1) in 2001-02, when children were aged around 9 months; and 2) in 2004-05, when children were aged 2 to 3.

United States: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS) program. Here the analysis considers data of the Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a sample of approximately 10 700 children born across the United States in 20015. This study considers data collected in the following waves: 1) in 2001-02, when children were 9 months old, and 2) in 2003-2004, when children were 2 years old.

Information about fathers’ use of leave around childbirth and fathers’ childcare is available for a sub-sample of cohort members. The reasons for this are work and residence related. First, fathers have to be employed in order to be entitled to paternity leave or annual leave around childbirth. Second, detailed information on paternal behaviour, such as childcare related activities, is difficult to collect from non-resident fathers. Therefore, the working sample is restricted to: 1) fathers who were in paid work at birth; and 2) fathers living with cohort member and with cohort member’s mother at birth and at the time of data collection of father’s activities. In addition, fathers had to complete the self-reporting questionnaire to be included in the analytic sample.

These sample restrictions mean that data concerns a “selected” group of children as those living in sole-parent families or with unemployed fathers are not included in the “analytic sample”. These restrictions are necessary for conducting the analysis but they need to be taken into account when interpreting findings.

All the analyses were adjusted using sampling weights in order to account for the stratifying nature of the surveys. This was done using the SVY commands of Stata.

3.1. Measurement of variables

The selection of variables in this study was driven by findings from previous studies examining parental-leave taking (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007; and, Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007) and fathers’ involvement (Baxter and Smart, 2011). The variables analysed here include: leave around childbirth (paternity, parental or annual leave); father’s involvement; and, a set of socio-economic control background variables.

Leave around childbirth – focal variable

The independent variable of main interest in the analysis is fathers’ birth-related leave. This includes paternity or parental leave as well as other time off taken by fathers at the time of birth such as holiday leave or other unpaid absences from work. In these cohort studies, parents were asked if fathers took a period of leave after the cohort member was born. In Australia, mothers provided information on fathers’ employment and leave use around the birth of the child. In addition, in three of the four countries, respondents were asked how many days fathers took off work to care for their child. Responses were converted into a categorical variable with the following groups: no leave, less than 1 week, 1 week, and 2 or more weeks. This categorisation was selected as the amount of days currently available in a number of countries is 1 week (5 working days). The MCS survey in the United Kingdom did not collect information on the number of days taken off work, but it distinguished between the different types of leave taken: paternity and or parental leave, annual leave and other kind of leave. In this case, a categorical variable was constructed with each type of leave representing a different category.

Father’s involvement

Father’s involvement is examined by considering the extent of engagement in caretaking and other child-related activities. This is likely to be a fairly narrow definition of paternal involvement as it does not include other important aspects such as accessibility, responsibility, or qualitative dimensions of parenting. Due to data availability, the definition used is limited, yet it provides a good insight into fathers’ involvement with their children.

In the four cohort studies, fathers were asked about the extent of involvement (frequency in the past month) in a number of childcare tasks. These included personal care as well as social and educational tasks and were asked in more than one wave of data collection. The type of activities differed across waves (as these are age-related) and between countries.

The analysis considers fathers’ involvement in childcare activities as an outcome variable. The focus is on fathers’ activities collected early in childhood. This information was collected before age one in Denmark, the United Kingdom and the United States. However, in Australia, information on fathers’ child-related activities was first collected when children were between 2 and 3 years old. At this age, fathers’ participation in childcare tasks was also asked in the United Kingdom and United States. Each activity was converted into a binary variable with a value of one if fathers were involved – if they performed the task frequently – and zero if not. The definition of “frequently” varied with the nature of the activity. For example, for bathing, fathers were considered to be “involved” when giving a bath several times a week, but for feeding, this had to take place at least once a day (Table 2).

Table 2.

Father’s child-related activities collected around childbirth and when child was between 2 and 3 years old.

| Before age 1 | Between 2 and 3 years old | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | UK | US | Australia | UK | US | Involvement = 1, if | |

| Personal care activities | at least daily | ||||||

| Assist child with eating | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | at least daily |

| Change child nappies or help use toilet | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | at least daily |

| Get child ready for bed or put child to bed | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | at least daily |

| Give child a bath or shower | √ | - | √ | √ | - | √ | few times per week |

| Help child get dressed/ready for the day | - | - | √ | √ | - | √ | at least daily |

| Looks after child on his own | - | √ | - | - | √ | - | at least daily |

| Help child brush her/his teeth | - | - | - | √ | - | √ | at least daily |

| Social and educational activities | |||||||

| Reading to the child | - | - | √ | - | √ | √ | at least three times per week |

| How often talk to child about school | - | - | - | - | - | - | at least daily |

| Play with the child | √ | - | - | - | √ | √ | at least daily |

| Eat an evening meal with child | - | - | - | √ | - | - | at least daily |

Socioeconomic characteristics – control variables

A number of socio-economic characteristics were included in the analysis to control for possible spurious associations between fathers’ leave and fathers’ involvement. The list of control variables includes:

Father’s characteristics: age at child’s birth; educational level; number of working hours at the time of data collection (classified into: less than 35 hours a week; 35 to 44 hours a week; and 45 hours or more); and, whether he was born outside the country.

Child characteristics: sex; age in months; ethnicity; foreign language spoken at home; whether child was born prematurely (<37 weeks); whether child was born with low weight at birth (<2.5 kilograms); child’s temperament; and, number of siblings.

Mother’s characteristics: age at child’s birth; educational level; employed during pregnancy; number of working hours at the time of data collection (classified into part-time (less than 35 hours a week) and full-time (35 hours a week or more); whether she was born outside the country; and, mental health.

Family characteristics: parents’ partnership status (married or cohabiting); family income; and, housing (owned or buying, rented privately or living in publicly subsidised, and other).

3.2 Analytical methods

First, the study will present descriptive statistics to gain a first insight into the characteristics of fathers who took time off work at childbirth compared with their counterparts who did not. These results inform how fathers taking leave differ from those not taking leave.

Second, the study uses multivariate logistic regressions for each of the father’s involvement binary outcome measures, controlling for leave taking (‘focal’ independent variable), child characteristics, and a number of socioeconomic characteristics. Amongst the latter, working hours is potentially endogenous; therefore, models were estimated without working hours and found that estimates remained unchanged. Models were run separately for each outcome variable, each age group and each country.

Issues around omitted variables and unobservable characteristics are considered. A bias from omitted variables may arise if fathers’ decisions to take paternity leave or to engage in childcare activities are correlated with unobservable characteristics such as fathers’ pre-birth commitment. The approach followed here is to make use of the rich set of variables in these datasets and control for as many variables that may allow reducing this selection bias. Nevertheless, estimates should be considered as indicative of associations rather than causal effects since it is not possible to completely eliminate individual heterogeneity.

Other methodological issues considered are attrition and missing data. Attrition is a major issue of longitudinal studies, especially when lost observations have characteristics that differ from those of the rest of the population. The attrition rates between the first two waves of data collection in the studies under consideration are relatively low (Gray and Smart, 2008 and Hansen and Joshi, 2007). Moreover, attrition analyses of cohort studies suggest that, even when cumulative attrition is high it does not affect the validity of the data (Nathan, 1999 and, Alderman et al., 2001). Hence, results presented here are likely to be unaffected by attrition.

In addition, missing data because of non-response to some questions can also affect results. To ensure that this is not the case, for each explanatory variable included in the analyses, information is included on whether such data is missing for a particular respondent. This is done by using a separate category for missing data when the variable is categorical and by including a mean value if variable is continuous. For the outcome variable, however, only cases that have complete information are included in the analysis.

3.3 Robustness tests

A number of robustness tests were carried out to examine whether the associations examined changed once the models accounted for other variables that could be associated with fathers’ leave taking as well as with child outcomes. First, supplementary analyses were conducted to account for maternal involvement because fathers’ behaviours are likely to be influenced by the degree of involvement of their partners. For instance, it may be that “assortative” mating means that within a couple, parents may have similarly positive or negative approaches to parenting, and so the involvement of one parent may be positively correlated with the involvement of the other (Baxter and Smart 2011). On the other hand, it may be possible that fathers with less involved partners may need to spend more time doing childcare-related tasks than their counterparts with more involved partners to compensate for the lack of maternal involvement. Hence, not accounting for maternal involvement may lead to overestimating father’s involvement. It is possible to run these tests for Australia and the United Kingdom as they collected data on involvement of a family member other than the father. For the case of Australia, the robustness test was estimated using an item about an adult in the household reading to the child (on 6-7 days per week, as opposed to less than this). Hence, the model controls for the involvement of a household member (results are presented under request). For the United Kingdom, this robustness test was estimated using indicators of the amount of time mothers spend with the child or how frequently they read to the child.

Second, supplementary models were estimated to control for possible selection bias associated with unobserved variables discussed above, such as fathers’ pre-birth commitment. Fathers who were committed to their partner and baby before the child was born are likely to be more engaged in childcare activities than less committed fathers. This additional analysis helps control for possible factors that may be correlated with both fathers’ leave-taking and involvement. These tests were run with data for the United Kingdom and the United States only because these were the countries which collected data on proxies for pre-birth commitment: attending pre-birth classes and present at delivery.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

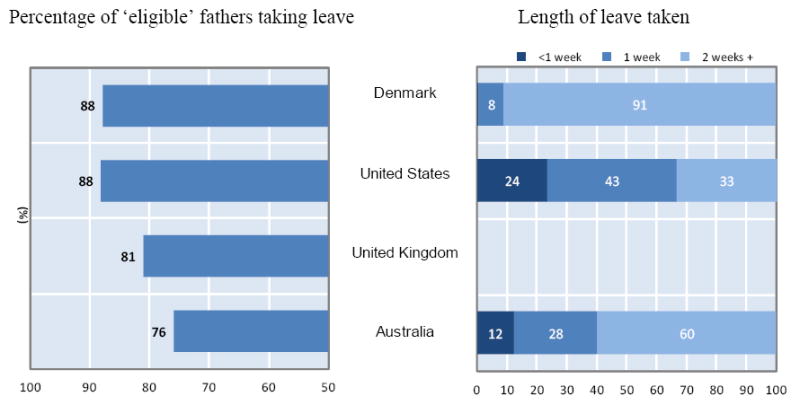

Descriptive statistics show fathers do take some time off work for parental purposes at the time children are born, despite the absence of legal provision (Figure 2). In the four countries analysed, the great majority - more than 80% - of resident working fathers took some time off work around childbirth. Cross-country differences in the proportion of leave-takers were small, with the largest proportion observed in Denmark (88%) and the United States (88%), and the smallest in Australia (76%). As mentioned above, “leave” here includes specifically designated paternity or parental leave, but can also include other time off taken by fathers at this time. This may include holiday leave or other unpaid absences from work.

Figure 2. Most fathers took some time off work around childbirth, but the number of days taken varied considerably across countries, circa 2000.

Note: Eligible fathers include: 1) those in paid work at birth and at the time of data collection of father’s activities; and 2) those living with cohort member and cohort member’s mother at birth and at the time of data collection of father’s activities. There is no data available on length of leave for the United Kingdom.

The length of leave among those who took leave, however, varied considerably across countries. As expected, Danish fathers took the longest period off work: of those who took any time off, 90% took two weeks or more and less than 1% took less than one week off. Australian fathers followed: almost 60% took two weeks or more, 28% took one week and 12% took less than one week. By contrast, US fathers did not take much time off work around childbirth: only 33% took more than two weeks off and 24% took less than one week. Information on the number of days taken off work by British fathers was not available. Yet, estimates from a national survey conducted at the time these fathers were likely to take leave indicate British fathers did not take much time off work around the time of birth of their child: 25% took more than 10 days, 37% took between 6 and 10 days, and 39% took between 1 and 5 days (Hudson et al., 2004). These patterns are close to those observed among fathers in the United States.

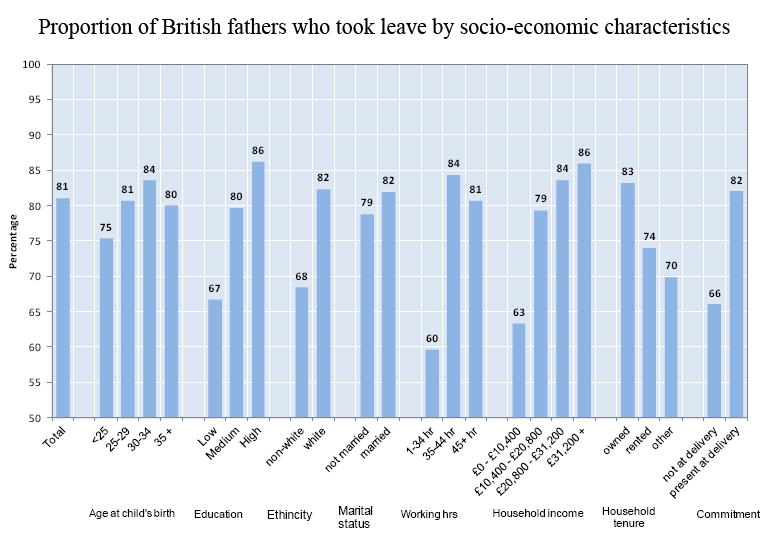

Figure 3 presents the proportion of British fathers who took time off around childbirth by fathers’ characteristics. These figures clearly show there are important socio-economic differences in leave-taking. Fathers who took leave were more likely to be aged between 30 and 34, to be highly educated, to be white, to be married, and to be more committed at birth (present at delivery room) than fathers who did not take some days off work. Furthermore, fathers who took leave were more likely to work full-time, though not very long working hours, to be in the highest income groups and to own a house than fathers who did not take time off work. Table A1 in Annex 1 presents descriptive statistics on father’s characteristics by leave-taking for the four countries.

Figure 3. Fathers from more advantaged backgrounds were more likely to take leave around childbirth than fathers from less advantaged backgrounds.

Note. All numbers were weighted using sampling weights.

Overall, these descriptive statistics indicate that fathers who take leave are more advantaged than fathers who do not take leave. These results are in line with other studies showing fathers who take leave tend to be those from more privileged backgrounds and with more secure and well-paid jobs (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007 and O’Brien and Moss, 2010). It is possible that, in the Anglophone countries, differences between fathers were larger because leave-taking is more likely amongst fathers for which a break from work does not represent a significant financial loss (O’Brien et al., 2007). On the other hand, differences were somewhat smaller in Denmark, where, at the time of data collection, legal provision of paternity and parental leave for fathers had been in place for several years (since 1984). Leave-taking amongst Danish fathers was therefore less driven by financial incentives, with leave-taking representing less of a financial burden to fathers on low income.

On the other hand, outcomes based on comparisons of leave-taking by the amount of days taken off work are likely to generate a different picture. In the Nordic countries, for example, there is a positive correlation between fathers’ work status and use of leave entitlements –the higher the income-status-occupation of fathers the more leave they take, except fathers with jobs at the very top (Duvander and Lammi-Taksula, 2012). Likewise, in the United States, taking longer periods of leave – two or more weeks – is associated with fathers being in middle- and high-prestige jobs, highly educated and native born (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007).

In sum, the sample here represents a group of more advantaged fathers as it excludes families with non-resident fathers and families with not-employed fathers. This should be born in mind when interpreting results as fathers and children from the most vulnerable groups are not examined.

Fathers’ leave-taking and father’s involvement

Table 3 shows the proportions of fathers who during the child’s first year of life regularly carried out a number of childcare activities according to leave-taking and country. Table 4 shows similar estimates but for fathers’ involvement at age 2-3 years. These statistics refer to any type of leave taken including annual leave, other leave and paternity or paternal leave. Fathers’ involvement is expected to differ according to the type of leave taken. The association is expected to be small for annual leave as this includes vacation; a somewhat larger association is expected with other leave as this includes taking days off beyond vacation; and the largest association with paternity leave.

Table 3.

Fathers who took leave were more likely to be involved in child-care related tasks when children were less than one year old than fathers who did not take leave.

| Fathers’ involvement when children were less than one year old, by leave-taking and country

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark: involvement before age 1 | United Kingdom: involvement before age 1 | United States: involvement before age 1 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| At least once a day | ||||||||||||

| Feed child | 28.9 | 29.7 | 23.2 | ** | 24.5 | 25.0 | 22.5 | *** | 41.7 | 42.0 | 40.1 | |

| Help child get dressed | - | - | - | - | - | - | 40.1 | 40.7 | 35.6 | * | ||

| Get child to bed | 21.2 | 21.6 | 18.4 | + | - | - | - | 55.0 | 55.1 | 55.2 | ||

| Diaper child | 47.5 | 48.7 | 39.0 | *** | - | - | - | 47.0 | 48.0 | 39.1 | *** | |

| Looks after the child on his own | - | - | - | 15.5 | 15.3 | 16.2 | - | - | - | |||

| Gets up at night for child | 18.7 | 18.6 | 19.3 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 13.7 | ** | - | - | - | ||

| Help child brush her/his teeth | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Evening meal | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| At least few times a week | ||||||||||||

| Give child a bath | 37.7 | 38.1 | 34.4 | 36.1 | 38.1 | 29.4 | *** | 53.4 | 53.6 | 52.1 | ||

| Read books to child | - | - | - | - | - | - | 26.5 | 26.9 | 24.1 | |||

| Play with the child | 77.0 | 77.5 | 73.4 | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Summary indicator of all items1 | ||||||||||||

| Low (1st tertile) | 34.4 | 35.0 | 29.9 | * | 35.7 | 33.7 | 44.2 | *** | 33.9 | 33.2 | 39.3 | * |

| Medium (2nd tertile) | 32.7 | 32.9 | 31.2 | 39.2 | 40.7 | 33.0 | *** | 34.5 | 34.7 | 32.3 | ||

| High (3rd tertile) | 33.0 | 32.1 | 39.0 | ** | 25.1 | 25.6 | 22.7 | + | 31.7 | 32.1 | 28.4 | |

Note:

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

The number of activities in each summary indicator was the following: 6 in Denmark; 4 in the United Kingdom; and, 6 in the United States.

Table 4.

Fathers who took leave were more likely to be involved in child-care related tasks when children were 2 -3 years old than fathers who did not take leave.

| Fathers’ involvement when children were 2 -3 years old, by leave-taking and country

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia: involvement at age 2-3 | United Kingdom: involvement at age 2-3 | United States: involvement at age 2-3 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | All | Took leave | No leave | p-value | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||

| At least once a day | ||||||||||||

| Feed child | 30.9 | 31.5 | 26.3 | + | - | - | - | 42.9 | 43.0 | 42.0 | ||

| Help child get dressed | 27.2 | 27.8 | 23.5 | + | - | - | - | 45.5 | 45.1 | 48.7 | ||

| Get child to bed | 26.3 | 27.9 | 19.3 | *** | 23.5 | 24.1 | 21.3 | ** | 60.5 | 61.0 | 56.7 | |

| Diaper child | 38.8 | 40.5 | 34.3 | ** | - | - | - | 41.8 | 42.3 | 38.0 | ||

| Looks after the child on his own | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Gets up at night for child | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Help child brush her/his teeth | 20.0 | 21.4 | 13.9 | ** | - | - | - | 34.1 | 34.2 | 33.6 | ||

| Evening meal | 54.8 | 53.5 | 55.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Take child outside to play | - | - | - | - | - | - | 29.3 | 29.1 | 30.2 | |||

| At least few times a week | ||||||||||||

| Give child a bath | 73.1 | 75.5 | 66.2 | *** | - | - | - | 23.2 | 23.2 | 23.4 | ||

| Read books to child | - | - | - | 23.0 | 24.2 | 18.5 | *** | 43.4 | 45.0 | 30.3 | *** | |

| Play with the child | - | - | - | 41.6 | 41.5 | 42.2 | - | - | - | |||

| Summary indicator of all items1 | ||||||||||||

| Low (1st tertile) | 29.0 | 24.3 | 30.5 | ** | 35.7 | 33.7 | 44.2 | *** | 33.9 | 33.2 | 39.3 | * |

| Medium (2nd tertile) | 32.4 | 30.1 | 33.6 | 39.2 | 40.7 | 33 | *** | 34.5 | 34.7 | 32.3 | ||

| High (3rd tertile) | 38.6 | 45.6 | 35.9 | *** | 25.1 | 25.6 | 22.7 | + | 31.7 | 32.1 | 28.4 | |

Note:

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

The number of activities in each summary indicator was the following: 7 in Australia; 3 in the United Kingdom; and, 8 in the United States

Overall, these figures suggest that fathers who took leave were more likely to be involved with their child on a regular basis than fathers who did not take leave. The activities that were carried out by a larger proportion of fathers during the first year of life included diapering, giving a bath and getting child to bed. Although the activities here reported differ across countries, it is possible to observe the highest proportion of involved fathers when children were less than one year old in Denmark (from 77.0% playing to 18.7% getting up at night) and the smallest in the United Kingdom (from 36.1% giving a bath to 15.3% getting up at night).

Similarly, Table 4 shows that, when children were aged 2-3 years old, fathers who had taken leave around childbirth were more likely to be involved with their child than fathers who did not take leave. In Australia and the United Kingdom, differences in involvement by leave taking were statistically significant for most activities; however, in the United States only reading to the child was more likely when fathers had taken some time off work. Nevertheless, it seems that the positive association between leave and involvement seems to prevail during child’s early years.

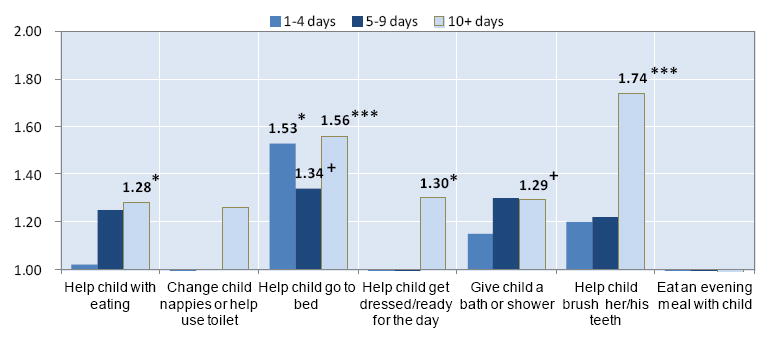

4.2. Multivariate results

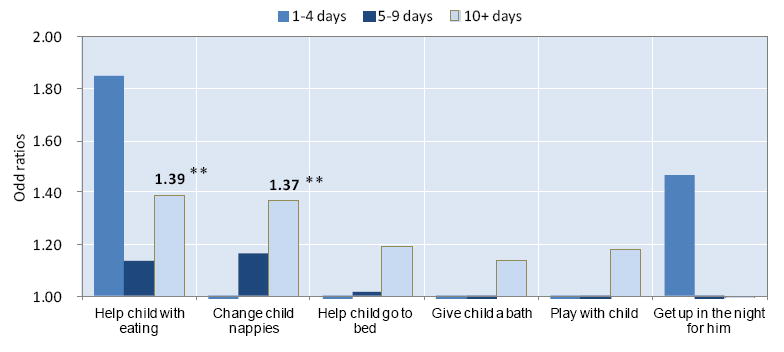

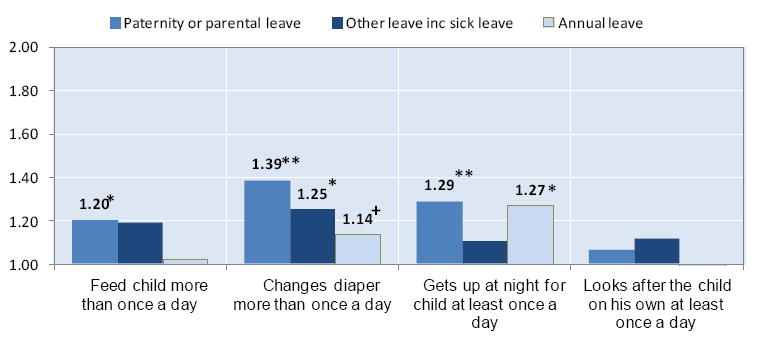

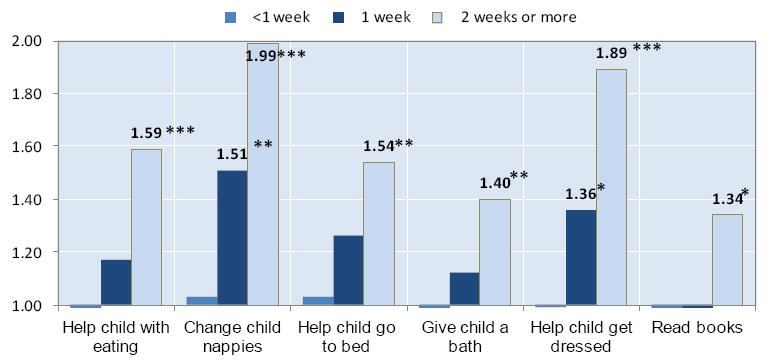

Figure 4 presents estimates of the relationship between fathers’ leave taking and different measures of fathers’ involvement after controlling for child, father, mother and family-related characteristics. The numbers shown are odds ratios. An odds ratio with a value of 1 indicates that involvement is equally likely amongst fathers in the specific leave-duration category and fathers who did not take leave (the omitted or reference category). An odds ratio greater (smaller) than 1 suggests that involvement is more (less) likely amongst fathers in the specific leave-duration category than fathers who took no leave. Only the odds ratios for which there is evidence that the result did not occur by chance – statistically significant – are presented.

Figure 4. Fathers’ leave-taking is associated with fathers’ involvement.

Australia – odds ratios of fathers’ leave-taking on fathers’ involvement when children were 2 to 3 years old

Denmark - odds ratios of fathers’ leave-taking by number on fathers’ involvement when children were around 6 months old

United Kingdom - odds ratios of paternity leave-taking and other types of leave on fathers’ involvement when children were around 9 months old

United States - odds ratios of fathers’ leave taking on fathers’ involvement when children were around 9 months old

Note: + p<.10;** p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

1. Estimates presented here were drawn from logistic multivariate regressions. Although not presented here, estimates belong to models that control for child-related factors (sex, age in months, ethnicity, whether child was born prematurely, weight at birth, whether foreign language spoken at home, number of siblings and temperament); paternal characteristics (age at child’s birth, born outside the country of study, educational level, number of working hours);, maternal characteristics (age at child’s birth, born outside the country of study, educational level, employment during pregnancy, working hours and mental health); and, family-related variables (parents’ partnership status, family income and housing).

2. Figures are odd ratios and the omitted category is fathers who did not take leave.

3. Fathers are defined as involved if they performed frequently the task: all tasks at least once a day, except giving a bath and reading which had to be carried out several times a week (Table 2).

In Australia, fathers who took 10 or more days off work around childbirth were more likely to be involved in childcare-related activities when children were 2 to 3 years old than fathers who did not take leave. For instance, fathers who took the longest periods of leave (10 or more days) were more likely to help their child with eating at least once a day than fathers who did not take leave (with an odds ratio of 1.28). The odds of being involved amongst fathers who took at least 10 days off were significant for all activities (odd ratios ranging between 1.28 and 1.74), except for changing diapers or helping the child use the toilet. In addition, even fathers who took shorter periods of leave (less than 10 days) were more likely to help their child go to bed than fathers who took no leave.

Amongst Danish fathers, the relationship between leave-taking and fathers’ involvement when the child was around 6 months old is somewhat weaker. Fathers taking 10 or more days of leave were more likely to be involved in feeding and changing diapers (odds ratios of 1.39 and 1.37 times, respectively) than fathers who did not take leave. However, for shorter periods of leave or for other activities, there is no evidence of a relationship. This weaker association is possibly explained by the fact that in Denmark there is a more equal share of childcare-related tasks between partners irrespective of the use of leave entitlements.

In the United Kingdom, leave-taking is also associated with fathers’ involvement when the child is around 9 months old. Estimates suggest that parental or paternity leave-taking is associated with regular paternal involvement. Fathers who took time off work through this type of leave were more likely to regularly participate in three out four activities than those not taking leave (1.39 times the odds of changing diapers; 1.29 times the odds of getting up at night for the child; and, 1.20 times the odds of daily feeding their child). Furthermore, it is clear that fathers who took time off through this type of leave were those showing the highest odds of involvement.

In the United States, taking some time off work around child birth is associated with higher odds of fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives, especially periods of leave of 2 or more weeks. Fathers who took two or more weeks of leave had greater odds of regularly carrying out all of the childcare-related tasks analysed here than fathers who took no time off work The odds were highest for changing nappies (odds ratio of 1.99) and smallest for reading books to the child (odds ratio of 1.34). It is possible that many more fathers engage in reading to their child than in doing personal care activities irrespective of their use of leave. Hence, taking time off work is positively associated with engagement in activities fathers would not do otherwise.

Tables A6 to A8 in the appendix show that fathers’ participation at ages 2 to 3 was also positively linked with some childcare activities. However, the relationship is not as strong. For instance, data for the United States shows that leave-taking was significantly associated only with two out of eight activities: getting child to bed and reading books. Once again, the association was observed mainly when leave-taking was equal to more than 2 weeks. As discussed previously, the literature shows that fathers’ childcare time declines with increasing age of the child with a peak around pre-school. However, it is possible that as children age fathers’ involvement concentrates more in social and educational activities such as reading, and less in personal-care. This is a topic that should be examined as future data becomes available.

Estimates presented in Figure 4 come from models that control for a wide set of factors that could influence fathers’ participation in children’s lives. Nevertheless, it is still possible that these results are driven by other unobserved characteristics that differ between fathers who take leave and those who don’t. For example, fathers who take time off work around childbirth may be a selected group willing to spend more time at home after childbirth irrespective of their leave entitlements. To control for possible differences in fathers’ commitment a supplementary analysis was conducted controlling for fathers’ pre-birth commitment to caring: present at delivery or attending pre-birth classes. These models were estimated for the United Kingdom and the United States, countries with this type of information. The robustness test shows the association between leave-taking and fathers’ involvement remained unchanged. That is, fathers who took paternity leave in the United Kingdom or 2 weeks or more of leave in the United States were more likely to be involved with their children than their peers who took no leave, irrespective of their commitment to parenting prior to child’s birth.

Finally, fathers’ leave-taking and involvement is likely to be influenced not only by mothers’ working practices (already accounted for in the models) but also by mothers’ involvement in childcare practices at home. The main models do not control for mothers’ involvement as this is likely to be endogenous. However, to test for the robustness of our results, an additional test was carried out to account for involvement of a family member other than the father. These models were run for Australia and the United Kingdom, countries with information on family’s time and mothers’ time respectively. Results from this additional model specification did not change the associations previously examined (estimates under request). Fathers who took leave had higher odds of regularly participating in childcare-related activities than fathers who did not, irrespective of the time mothers or other family members spent with children.

Although we control for a rich set of variables, it is possible that some unobserved factors are driving the association between leave-taking and involvement. It might be possible to estimate the influence of such factors through alternative methods such as two-step estimation models. This is an important topic to explore as it may provide useful information for policy recommendations.

5. Conclusions

Using longitudinal data from four OECD countries – Australia, Denmark, the United Kingdom and United States – this paper conducted for the first time a cross-national analysis of the associations between fathers’ leave and fathers’ involvement. Results showed a positive and significant association between fathers’ leave taking and fathers’ involvement with their children. Fathers who took long periods of leave (of two or more weeks) were likely to engage more regularly in childcare activities than their peers who did not take time off at the time of birth. In general, results were consistent across countries.

In the four OECD countries analysed, an overwhelming majority of fathers – around 80% or more – took some time off work around childbirth. This percentage was highest in Denmark, but it was also high in the Anglophone countries, where at the time these children were born there were no statutory paid leave entitlements for fathers. This suggests that fathers are interested in taking time off work to be around their children when these are born. On the other hand, the number of days off work differed markedly across countries. The largest proportion of fathers taking two or more weeks was observed in Denmark (90%) and the smallest in United States (33%). Difference in number of days is clearly related to differences in leave entitlements between Denmark and the Anglophone countries.

The characteristics of fathers who took time off work during the child’s first year of life differed markedly from those who did not take leave. The former tended to be from more advantaged backgrounds (to be highly educated, native-born, married, to work full-time, to have high incomes) than the latter. Differences in leave taking by fathers’ socio-economic characteristics were smaller in Denmark, where legal provision of paternity and parental leave for fathers has been in place for almost three decades (since 1984). By contrast, in the Anglophone countries, leave policies for fathers were unavailable at the time children in these cohort studies were born, early 2000s. In these countries, children in less advantaged households are more likely to start with some inequalities including lack of father’s availability and involvement.

One limitation of this study is that the sample analysed over-represents better-off fathers and their children as it only included couple-parent families with working fathers. In addition, this study does not distinguish between biological and social fathers (step-fathers or mothers’ cohabiting partners). However, some evidence suggests that social fathers engage in parenting practices of equal quality than those of biological fathers (Berger et al., 2008). Hence, not making this differentiation is unlikely to influence our results. It is the most vulnerable children, those growing up in sole-parent families, who are excluded from this study. These children are likely to have reduced contact with their fathers. Thus, they are less likely to benefit from fathers’ involvement than their peers living with a resident social or biological father.

Results here showed fathers’ leave-taking is associated with involvement in childcare activities, especially periods of leave of two or more weeks. Fathers in Australia, Denmark and the United States were more likely to be involved in childcare-related tasks during the early years (e.g., helping the child to eat, changing diapers, getting up at night for the child) when they took periods of leave of two or more weeks compared with fathers who did not take leave. Fathers in the United Kingdom who took parental or paternity leave during the child’s first year of life were also more likely to participate in children’s lives than fathers who did not take time off work.

Estimates showed that fathers’ leave taking was also associated with involvement beyond the period around childbirth, at 2 to 3 years of age. However, there is some indication that it the relationship is somewhat weaker. Future work could investigate whether fathers’ involvement during the early years continues as children age and whether this translates into positive outcomes. This would provide further evidence to support policies that encourage fathers to participate in children’s lives.

The paper controls for a rich set of variables to attempt to mitigate for potential unobserved heterogeneity. Two supplementary analysis, including controls for pre-birth father’s commitment to his partner and baby, were carried out. Results remained practically unchanged. Nevertheless, although the paper has attempted to control for a wide set of factors that could potentially bias the relationship between leave-taking and involvement, it is very likely that the paper has not controlled for all factors. The paper cannot identify with certainty the reason behind the positive correlation between leave-taking and involvement, but documenting the correlation is an important contribution in this little-studied area.

Three notes of caution on the interpretation of these findings are warranted. First, estimates should be considered as indicative of associations rather than causal effects since it is not possible to control for all factors influencing leave-taking and care-taking. Second, cross-country comparisons should be made with caution as data comparability is not always straightforward. Data on leave-taking in the United Kingdom did not include amount of time taken, but type of leave taken. Hence, for this particular country, the paper is not able to investigate whether length of leave is associated with fathers’ involvement. Additionally, the type of childcare-related activities differs across waves (as these are age-related) and between countries. Therefore, although these include activities in early childhood reported by fathers themselves, the difference in items warrants against direct cross-country comparisons. Third, these data do not lend to immediate generalisation since they refer to leave-taking and caring behaviours of fathers in four specific countries in the late 1990s, early 2000s. Therefore, they reflect the experiences of fathers taking leave in a specific year and living in a specific context.

Parental leave is one of many polices that could contribute to a more equal share of caring and earning between parents. Parental leave polices, however, need to be well-designed to be attractive to working parents and need to be complemented with other family-friendly policies, such as flexible working practices and availability and support for childcare services. Where needed, policy should also contribute to changing mind-sets and inform parents on the important role fathers play in children’s development. Communication campaigns could be developed to promote men’s use of leave entitlements and other workplace family-friendly practices. Similarly, pre- and postnatal visits could be used as an opportunity for informing parents about the importance of both maternal and paternal involvement on child development and the importance of getting involved early in life.

This study adds to the evidence that today’s fathers are involved in early childcare and suggests that parental leave for fathers is positively associated with subsequent paternal involvement. The majority of fathers in the four countries analysed took time off work to be with their children around childbirth, irrespective of the leave policies in place. However, only in Denmark, where parental leave policies for fathers have been running for 30 years, a majority of fathers took long periods of leave (two or more weeks). The evidence also showed that long periods of leave are positively associated with parental involvement. Further research is needed to examine whether fathers’ involvement continues as children grow up and whether greater involvement is associated with positive child outcomes. The correlational nature of this work does not allow giving firm policy recommendations, but it provides some insight into the role of fathers as carers, a field much understudied.

ANNEX: STATISTICAL TABLES

Table A1.

Fathers’ characteristics by leave-taking around childbirth (columns add 100% per category)

| Australia | Denmark | United Kingdom | United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | |

| Father’s age | ||||||||||||

| <25 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 10.5 | *** | 14.4 | 20.7 | ** | ||

| 25-29 | 15.2 | 12.9 | 30.2 | 24.6 | * | 20.8 | 21.4 | 24.5 | 20.8 | + | ||

| 30-34 | 39.5 | 33.5 | ** | 38.7 | 35.3 | 38.1 | 32.2 | *** | 31.4 | 30.1 | ||

| 35+ | 42.9 | 50.0 | ** | 25.1 | 33.5 | *** | 33.7 | 35.9 | + | 29.8 | 28.5 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Father’s education | ||||||||||||

| Low | 9.6 | 14.0 | ** | 26.7 | 33.3 | ** | 8.0 | 18.2 | ** | 11.0 | 20.4 | *** |

| Medium | 56.5 | 58.6 | 63.3 | 57.2 | ** | 50.7 | 54.7 | 51.9 | 52.7 | |||

| High | 33.9 | 27.4 | ** | 10.1 | 9.5 | 41.4 | 27.1 | *** | 37.1 | 27.0 | *** | |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Foreign born (vs native-born)1 | 21.6 | 26.4 | * | 2.6 | 4.5 | * | 7.6 | 15.0 | *** | 18.2 | 30.2 | *** |

| Cohabiting (vs married) | 14.3 | 13.6 | 41.1 | 42.5 | 26.3 | 30.4 | *** | 13.6 | 20.6 | *** | ||

| Father’s usual working hours | ||||||||||||

| not employed | 2.1 | 6.2 | *** | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| <35 hours | 4.2 | 9.6 | *** | 1.9 | 5.3 | *** | 3.5 | 10.1 | *** | 4.4 | 8.7 | *** |

| 35-44 hours | 41.6 | 27.0 | *** | 69.5 | 39.1 | *** | 41.9 | 33.7 | *** | 48.0 | 43.2 | * |

| 45 or more | 52.2 | 57.3 | * | 28.6 | 55.6 | *** | 54.5 | 56.3 | 47.6 | 48.2 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Father’s commitment at birth | ||||||||||||

| Was present in delivery room | - | - | - | - | 94.3 | 87.4 | *** | 96.5 | 87.8 | *** | ||

| Attended birth class | - | - | - | - | - | - | 48.2 | 35.7 | *** | |||

| Household income 2 | ||||||||||||

| lowest 20% (approx) | 9.4 | 21.1 | *** | 17.9 | 35.3 | *** | 4.4 | 11.4 | *** | 10.1 | 19.0 | *** |

| 2nd quintile | 18.0 | 17.6 | 20.8 | 14.5 | *** | 32.0 | 37.5 | *** | 20.4 | 26.7 | ** | |

| 3rd quintile | 23.8 | 20.4 | + | 21.1 | 11.9 | *** | 29.4 | 25.9 | *** | 39.0 | 33.8 | * |

| 4th quintle | 23.3 | 16.4 | *** | 20.9 | 13.4 | *** | 34.2 | 25.2 | *** | 30.5 | 20.5 | *** |

| top 20% | 21.5 | 18.6 | 19.3 | 24.7 | *** | - | - | - | - | |||

| missing | 4.1 | 6.0 | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Household tenure | ||||||||||||

| own/buying | 77.5 | 74.7 | 69.9 | 65.1 | ** | 81.5 | 70.3 | *** | 65.6 | 50.0 | *** | |

| rent/board | 19.9 | 19.4 | 28.3 | 34.0 | ** | 15.8 | 24.7 | *** | 29.2 | 44.4 | *** | |

| other | 2.6 | 5.9 | *** | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 5.0 | *** | 5.2 | 5.9 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Sample size 3 | 2293 | 704 | 3310 | 462 | 8,709 | 2,524 | 4,050 | 500 | ||||

Note. All numbers were weighted using sampling weights. Significance tests were conducted to compare fathers who took any leave with those who took no leave.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

For the UK, figures represent non-white (vs. white).

For the UK, household income is grouped as follows: £0-£10,400; £10,400-£20,800; £20,800-£31,200; £31,200 +. For the US, the categories are: $0-$20,000; $20,001-$35,000; $35,001-$50,000; $50,001+.

Sample sizes reported in the paper are rounded to the nearest to 50 in accordance with NCES requirements.

Table A2.

Child, mother and family characteristics by fathers’ leave-taking (columns add 100% per category)

| Australia | Denmark | United Kingdom | United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | Took leave | No leave | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | (%) | (%) | p-value | |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Boys (vs. girls) | 47.3 | 50.9 | 52.3 | 50.4 | 51.0 | 51.5 | 51.3 | 53.0 | ||||

| Age in months | 8.7 | 8.8 | - | - | 9.2 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 10.4 | ||||